Abstract

Blood cell development in the Drosophila lymph gland is controlled by multiple factors, most of them conserved from flies to mammals. The Drosophila homolog of vertebrate PDCD2, Zfrp8, is required in Drosophila hematopoietic stem cell development. Zfrp8 mutant larvae show a disruption of homeostasis in the lymph gland and vast lymph gland overgrowth. The loss of one copy of Zfrp8 also causes a lymph gland enlargement. This dominant phenotype can be modified by heterozygous mutations in cell-cycle genes and several genes functioning in blood development. To identify additional genes that function in hematopoiesis, we screened a collection of second and third chromosome deficiencies for modifiers of Zfrp8 heterozygous phenotype. Using deficiency mapping, available single gene mutations, and RNAi lines, we identified several novel factors required for lymph gland development and hemocyte differentiation. Distinct lymph gland phenotypes of nine of these genes are reported here for the first time. Importantly, the orthologs of four of them have a role in mammalian blood development and leukemogenesis. Our work has shown that the number of genes regulating normal blood cell development in Drosophila is much larger than expected, and that the complex molecular mechanisms regulating hemocyte differentiation are comparable to those in vertebrates.

Keywords: lymph gland, Drosophila, hematopoiesis, Zfrp8

In vertebrates, hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) give rise to at least eight hematopoietic lineages. Studies of signaling pathways and transcription factors revealed a number of factors controlling decision points in hematopoiesis. The differentiation along each lineage is orchestrated by transcription regulators, including PU.1, Foxo1, EBF1, Runx, and GATA factors. Notch, JAK/STAT, and Wingless (Wg) signaling are implicated in regulation of self-renewal [reviewed in Mercer et al. (2011) and Orkin and Zon (2008)]. Modern genomic approaches uncovered many more genes expressed during blood cell differentiation and identified regulatory networks involving hundreds of transcription factors (Novershtern et al. 2011). Although the role of transcriptional control in hematopoiesis cannot be underestimated, pre- and posttranscriptional mechanisms also play important roles in hematopoiesis, but only few examples have been studied (Baou et al. 2011; Sardina et al. 2011; Yoshida et al. 2011).

Hematopoiesis in Drosophila is simpler than in vertebrates and results in the differentiation of three major types of hemocytes: plasmatocytes, crystal cells, and lamellocytes [for review see (Crozatier and Meister 2007; Evans and Banerjee 2003; Lanot et al. 2001; Lebestky et al. 2000]. Like in humans, the best-characterized genes in Drosophila hematopoiesis are transcription factors and genes encoding components of signal transduction pathways. For example the transcription factor lozenge (Lz), a Runx domain protein, is required for crystal cell specification, and the GATA transcription factor pannier (Pnr) is essential for plasmatocyte development (Lebestky et al. 2000; Minakhina et al. 2011). Jak/Stat signaling controls several processes, including both plasmatocyte and lamellocyte differentiation (Luo et al. 2002; Minakhina et al. 2011). The Wingless (Wg), Hedgehog (Hh), and Notch pathways also function at several stages of lymph gland development (Mandal et al. 2007; Mukherjee et al. 2011; Muratoglu et al. 2006; Sinenko et al. 2009; Tokusumi et al. 2010). Recent studies by Avet-Rochex et al. (2010) suggest that hemocyte differentiation relies on diverse cellular mechanisms, but genes other than transcription factors are not well studied in vertebrates and invertebrate models.

Drosophila lymph gland structure and development

In Drosophila, the lymph gland is the major source of adult hemocytes and has been developed as a model to study hematopoiesis. The lymph gland is established during embryogenesis as paired clusters of cells associated with the cardiovascular system, alongside the dorsal vessel (Jung et al. 2005; Mandal et al. 2004). Clonal analysis shows that embryonic and first-instar lymph glands contain pluripotent cells with the ability to form cell lineages, reminiscent of vertebrate HSCs (Minakhina and Steward 2010). After the transition to the second-instar larval stage, the pluripotency is no longer observed (Krzemien et al. 2010). During the second- and third-instar larval stages, the lymph glands expand and form primary lobes and a series of secondary and tertiary lobes located posterior to the primary lobes alongside the dorsal vessel (Figure 1A). At the third-instar stage, the primary lobe can be subdivided into three structurally distinct compartments: the medullary zone (MZ), with tightly packed cells located proximally to the dorsal vessel; the petal-shaped distal cortical zone (CZ); with larger and more loosely packed cells; and a hematopoietic niche, the posterior signaling center (PSC; Figure 1, B and C) (Jung et al. 2005; Krzemien et al. 2007; Lebestky et al. 2003; Mandal et al. 2007).

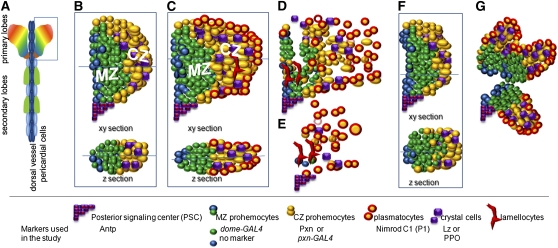

Figure 1 .

Schematic representation of the lymph gland structure. (A) Whole lymph gland with primary and secondary lobes. (B–C) Cross-sections and z-sections of normal primary lobe of middle (B) and late (C) third-instar larval lymph glands. MZ prohemocytes expressing dome-GAL4 are shown in green. Prohemocytes expressing no markers are blue. CZ prohemocytes expressing Pxn are shown in yellow, crystal cells are purple, and lamellocytes are elongated red cells. Plasmatocytes (encircled in red) first differentiate at the surface of the CZ. (D, E) Primary lobes disintegrate upon metamorphosis or in response to immune challenge. Disintegration is also observed in a number of mutants as a result of accelerated hemocyte differentiation. (F, G) Examples of abnormally shaped primary lobes observed during the screen. Markers and their expression used in this study are indicated below the drawing.

By the middle of third instar, MZ cells become quiescent, while the cells in the CZ keep proliferating and the CZ expands till pupariation (Jung et al. 2005; Krzemien et al. 2010; Minakhina et al. 2011). The CZ contains hemocytes at different stages of differentiation. The majority of these cells are called intermediate progenitor cells (Krzemien et al. 2010) or CZ prohemocytes (Minakhina et al. 2011) (Figure 1, yellow). These cells express the intermediate marker, peroxidasin (Pxn), do not express terminal differentiation markers, and are able to proliferate (Jung et al. 2005; Krzemien et al. 2010; Nelson et al. 1994). During the late third instar and metamorphosis, hemocytes mature into plasmatocytes, crystal cells, and lamellocytes, and they are released into circulation (Grigorian et al. 2011) (Figure 1, C–E). In normal, unchallenged larvae, the maturation of CZ prohemocytes into plasmatocytes, the predominant blood cell type, starts at middle-to-late third instar at the surface of the CZ (Figures 1C and 2, A, A′, and F) and culminates at pupariation (Grigorian et al. 2011; Jung et al. 2005; Kurucz et al. 2007a,b; Minakhina et al. 2011). Crystal cells are seen in a scattered pattern throughout the CZ (Figures 1, 2, and 6). The third type of Drosophila blood cells, the large and flat lamellocyte, is rare in normal lymph glands. Upon immune challenge, the numbers of mature plasmatocytes as well as lamellocytes increase substantially, and the lymph gland often disintegrates before pupariation (Figure 1, D and E) (Markus et al. 2009; Rizki and Rizki 1992; Sorrentino et al. 2002).

Figure 2 .

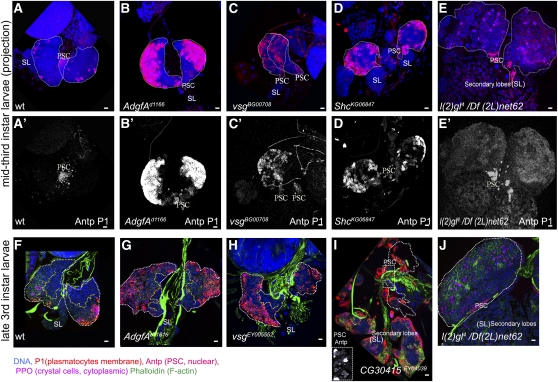

Lymph gland phenotypes of Zfrp8null/+ overgrowth suppressors. (A–E, A′–E′) Confocal projections of middle third-instar larval lymph glands. Lymph gland primary lobes are outlined by white dotted line. Normal wild-type glands have few or no plasmatocytes (P1, membrane marker, red A, A′). The number of plasmatocytes in Agdf-Ad11616, vs.gBG00708, and ShcK66847 homozygous mutants (B–D, B′–D′) is drastically increased, compared with that in wild-type (A, A′). PSCs are stained with anti-Antp (nuclear, red). Red channel (Antp and P1) for each projection is shown in (A′–E′). Crystal cells are stained with anti-PPO (cytoplasmic marker, pink). Primary lobes are outlined with white dotted line. Secondary lobes (SL) in (A–D) do not express differentiation markers. (F–J) Confocal cross-sections through the inner layers of late third-instar larval lymph glands. The border between MZ and CZ is shown by yellow dotted line. (F) In wild-type larvae, plasmatocyte maturation is seen in the surface layers (P1, membrane marker, red) of the CZ. Agdf-Ad11616 and vsgEY05552 lymph glands show plasmatocyte differentiation across all CZ layers and also a significant reduction of MZ size (J, H). (I) CG30415EY040039 caused an increase in plasmatocytes, disintegration of the primary lobes, and enlargement and increased differentiation of secondary lobes. The prospective positions of primary lobes (white dotted outline) were identified by the presence of the PSCs (anti-Antp, nuclear red, rectangular inset). (E, E′, J) l(2)gl4/Df(2L)net62 causes lymph gland overgrowth with relatively weak staining for P1 at the surface of the lobes. Staining with phalloidin (green in F–J) shows cell shape allowing detection of lamellocytes and strongly stains heart tube. DNA is shown in blue. Scale bars are 10 μm.

Figure 6 .

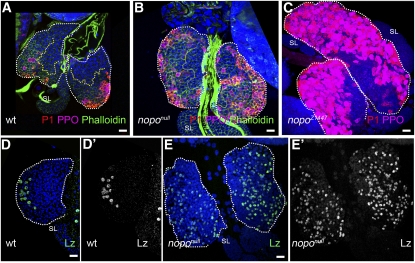

nopo affects lymph gland growth and hemocyte differentiation. Primary lobes are outlined with white dotted line. Crystal cell (anti-PPO2, pink) and plasmatocyte maturation (P1, membrane, red) are increased in middle third-instar (B) and late third-instar (C) noponull lymph glands compared with that in wild type (A). Secondary lobes (SL) do not express differentiation markers. Confocal cross-sections through the inner cell layers (A, B) show drastic decrease in mutant MZ size (yellow dotted line). Staining with phalloidin (green) shows cell shape. Staining for Lozenge (Lz), an early crystal cell marker (D–E′, green/white), shows greater than 5 times increase in number of crystal cells in noponull lymph gland lobes (E, E′) compared with that in wild type (D, D′).

Identification of genes controlling normal hematopoiesis

Recently we reported a novel conserved factor, Zfrp8, that functions in Drosophila hematopoiesis. Zfrp8 mutants show a loss of the MZ-CZ organization and vast overproliferation of CZ prohemocytes, leading to an increase in all three types of hemocytes, particularly lamellocytes (Minakhina et al. 2007; Minakhina and Steward 2010). In Zfrp8 heterozygous animals, the size of the lymph gland is 2–2.5 times enlarged. Using clonal analysis, we showed that Zfrp8 is required in early lymph gland development for the viability or division of HSCs and that the lack of Zfrp8 does not cause cell-autonomous overproliferation (Minakhina and Steward 2010). Therefore, loss of one or both copies of Zfrp8 changes the homeostasis within the lymph gland and causes overproliferation of hemocytes at intermediate stages of differentiation in noncell autonomous manner.

Previously we showed that the Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland phenotype can be modified by dose reduction of genes that control cell proliferation and by genes functioning in hemocyte development (Minakhina et al. 2007, 2011). We identified two enhancers, Dgrip91, which involved in anchoring gamma-Tubulin to the centrosome, and Cdc27, which is a component of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC). The GATA factor gene pannier (pnr) was identified as a suppressor of Zfrp8null/+ and Zfrp8null/Zfrp8null lymph gland overgrowth (Minakhina et al. 2007). Further studies have shown that pnr is required for plasmatocyte differentiation and that the balance between the two Pnr isoforms, Pnr α and β, controls hemocyte proliferation (Minakhina et al. 2011). This finding suggested that Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth may be manipulated by changes in cell proliferation as well as differentiation.

We performed a genetic deficiency screen designed to identify modifiers of the dominant Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland phenotype. We found 21 deficiencies that altered the phenotype. Further analysis of 9 of these deficiencies identified 11 suppressors and four enhancers of Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth. Two of the enhancers, mutagen-sensitive 304 (mus304) and no poles (nopo) are reported regulators of the cell cycle. The genes suppressing Zfrp8 overgrowth mostly controlled plasmatocyte differentiation and changed the homeostasis between prohemocytes and mature blood cells.

The large number of deficiencies and new genes identified suggest that our screen is far from saturated and that only a small portion of the genes functioning in Drosophila hematopoiesis are known so far. We describe the hematopoietic phenotypes of 10 genes. Of these, 9 genes were not previously reported to function in Drosophila hematopoiesis, and 4 of them have mammalian orthologs with a role in blood development and leukemogenesis. Thus, hematopoiesis in flies is more complex than previously demonstrated, and in its complexity it is even more similar to blood formation in vertebrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains, collection of larvae, and Zfrp8 genetic interactions

Zfrp8Df(2R)SM206 was used as the Zfrp8null allele (Minakhina et al. 2007; Minakhina and Steward 2010). Fly stocks bearing the mutations nopoZ1447 and noponull (nopoExc142) were kindly provided by Dr. L. A. Lee (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN); and pxn-GAL4 and 2x-UASGFP by Dr. U. Banerjee (University of California, Los Angeles, CA). Collection of deficiencies uncovering the second and third chromosomes of the genome, drivers, balancer stocks, smaller deficiencies, mutant alleles, and P-element insertions were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN). UAS-dsRNA (RNAi) transgenic lines were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC) and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (TRiP lines) (Dietzl et al. 2007; Ni et al. 2011). Deficiencies, mutant alleles, and RNAi lines are listed in Tables 1 and 2 and Table S1. tub-Gal4 UAS-dcr2/TM6b was used for strong general gene knockdown, and dome-GAL4/FM7, UAS-cd8GFP was used for MZ visualization and knockdown in the MZ. T(2;3)B3, CyO;TM6B Tb1, GlaBC, and GFP-marked balancer chromosomes were used to identify mutant larvae. w118, driver/+, and UAS-RNAi animals were used as wild-type controls.

Table 1 . Summary of the screen for genetic modifiers of Zfrp8/+ lymph gland phenotype.

| Deficiency Modifying Zfrp8/+ Lymph Gland Overgrowth | Deleted Segment, Cytology | Numbers of Lymph Glands with Phenotype/ Total Analyzed | Comment on Mapping | Modifying Alleles and RNAi Lines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suppressing | ||||

| Df(2L)BSC31 | 23E5–23F5 | 7/13 | Smaller deficiencies tested, no modifiers found. | n/i |

| Df(2L)BSC17 | 30C3–30F1 | 14/14 | Mapped to 30C1 and 30C5. Two dominant suppressors identified. | pelo1, hoipk07104 |

| Df(2R)cn9 | 42E–44C1 | 20/27 | Not mapped. | n/i |

| Df(2R)BSC29 | 45D3–45F6 | 7/12 | Mapped to 45F5–46A1. | CG30338 {v 29189} |

| Df(2R)en-A | 47D3–48B2 | 6/11 | Not mapped. | n/i |

| Df2R)BSC11 | 50E6–51E4 | 10/10 | Mapped to 51A5—51C1. | n/i |

| Df(2R)PC4 | 55A1–55F2 | 9/10 | Mapped to 55B11–55C9. | nopo {v104477} Idgf5 {v100977} |

| Df(2R)BSC22 | 56D7–56F12 | 10/19 | Not mapped. | n/i |

| Df(2R)vir130 | 59B1–59E1 | 17/17 | Smaller deficiencies tested, no modifiers found. | n/i |

| Df(2R)or-Br6 | 59D5–60B8 | 13/24 | Weak modifier mapped to 59D9. | CG30415EY04039 |

| Df(2R)M60E | 60E6–60E11 | 20/21 | Not mapped. | |

| Df(3L)BSC23 | 62E8–63B6 | 8/12 | Not mapped. | |

| Df(3L)AC1 | 67A2–67D13 | 10/14 | Two dominant suppressors identified. | shcKG06847, vs.g EY05552, MTF-1 {v107124} |

| Df(3L)Pc-2q | 78C5–79A1 | 9/15 | Not mapped. | n/i |

| Df(3R)mbc-30 | 95A5–95C11 | 9/10 | Mapped to 95B1–95D1. | n/i |

| Modifying | Phenotype of trans-heterozygous lymph glands. Comment on mapping. | |||

| Df(2L)net-PMF | 21A1–21B8 | 9/12 | Small CZ. Both enhancer and suppressor are found. | l(2)gl4, smo3 |

| Df(2R)Egfr5 | 57D2–58D1 | 9/9 | Small lymph gland with changed morphology. Not mapped. | n/i |

| Df(3L)emc-E12 | 61A–61D3 | 21/28 | Lymph glands are enlarged and disintegrated. Enhancing region mapped to 61A5–61B1 and one suppressing gene mapped to 61B1. | Pk61CEP3091, Pk61C5, |

| Df(3L)W10 | 75A6–75C2 | lethal | Smaller deficiencies do not show lethality. Enhancing region is mapped to 74D1–75B11 Enhancer and suppressors found. | Eip75BA81, Adgf-Ad11616, mus304D3, n/i |

| Df(3L)BSC249 | 79B2–79D1 | 11/11 | Disintegrated primary lobes. Not mapped. | n/i |

| Df(3R)ME15 | 81F3–82F7 | 14/14 | Disintegrated primary lobes. Not mapped. | n/i |

| Zfrp8-independent phenotypes | Lymph gland phenotype of deficiency/+ | Comment | ||

| Df(2L)ast2 | 21D1–22B3 | 15/15 | Lymph gland disintegration mapped to 21D4-21E2. | Ush, lwr are known to cause hematopoietic phenotype |

| Df(2L)c144 | 22F4–23C3 | 15/17 | Increased size and differentiation. | |

| Df(2L)spdj2 | 27B2–27F2 | 10/10 | Decreased size and small CZ. | |

| Df(2R)cn9 | 42E–44C1 | 27/27 | Decreased size, increased differentiation. | |

| Df(2L)TW161 | 38A6–40B1 | 8/11 | Decreased size, increased differentiation. | |

| Df(3L)XG5 | 71C2–72C1 | 19/19 | Enlarged cortex. | |

| Df(3R)BSC38 | 85F1–86C8 | 6/10 | Enlarged. | |

| Df(3R)T-32 | 86D9–87C4 | 13/17 | Enlarged disintegrated. | |

| Df(3R)ea | 88E7–89A1 | 18/18 | Enlarged disintegrated. | |

| Df(3R)crb87-5 | 95F8–96A20 | 20/20 | Primary lobe enlargement. |

Columns 1 and 2 show the deficiencies that modify the Zfrp8null/+ phenotype in more than 50% of the lymph glands and their cytological location. Column 3 shows the number of lymph glands with modified phenotypes relative to the total number analyzed. Column 4 shows the smallest cytological interval to which the modifying effect was mapped. Column 5 lists the genes that were found to have modifying effect. n/i, modifying genes were not identified.

Table 2 . Alleles and RNAi lines tested for modification of Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland phenotype.

| Genomic Region | Number of Annotated Genes | Tested Alleles | Tested RNAi Lines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21A1–21B8 | ∼50 |

kis1 spen3 smo3 l(2)gl4 NheDP01088 |

mbm {v18699} CG17075 {v103741} CG33635 {v48812} CG11604 {v18699} |

| 30C1 | 5 |

GlcAT-S {v42779} Trx2 {v104629}, |

|

| 30C5 | 6 |

pelo1 hoipk07104 Pka-C1DN |

|

| 45F5–46A1 | 16 |

updoKG01041 mmp2k00604 Map60KG00506 |

Not1 {JF01135} RpL31{v104467} CG30338 {v29189} CG30340 {v100088} |

| 51A5–51C1 | ∼30 |

Tra2B ttv00681b ttvG00158 Sec61β07214 Uhg5EY04055 |

Sec61β {v107784} Su(var)2-HP2 {JF01994} M-spondin {v107608} CG12858 {v1688} |

| 55B11–55C9 | ∼60 |

OteB279 lolalk02512 sbbBG01610 Dp1BG02288 imdBG02288 fjdl |

nopo {v104477} lolal {JF01419} pen-2 {JF02608} sbb {JF02375} Idgf5 {v100977} |

| 59D9 | 9 |

CG13551e03979 CG30415EY04039 |

|

| 61A5–61D3 | ∼130 |

Pk61CEP3091 CG13887EY2104 thoc7G4736 CG16940G4736 |

NitFhit {v27830} pyx {JF01242}, CG13887 {v106452} mri {JF01921} |

| 67A2–67D13 | ∼150 |

ShcKG06847 Uch-L3j2B8 phol81A vsgEY05552 vsgEY05552 fry7 nbs1 RpS174 NF-YAKG06786 CG13887EY21004 |

MTF-1 {v107124} CG3911, {21738} NF-YA {JF02013} LanB2 {v104013} CG33696 {v101076} CG16719 {102653} CG18177 {101408} |

| 74D1–75B11 | ∼90 |

Eip75BΔ51 Adgf-Ad11616 mus304D3 mus304D1 NUCB1c01508 CG5589f06152 |

Seventy genes from 10 genomic regions were tested for their ability to modify the Zfrp8/+ lymph gland phenotype. Column 2 shows the approximate number of annotated genes in each region. Columns 3 and 4 show the alleles and RNAi lines tested for modifying effect. The ID of each RNAi line is shown in braces.

Larvae were grown on standard cornmeal/molasses food at 25° until they reached the third-instar larval stage. Late third-instar larvae were collected 6–12 hr before pupariation. Middle third-instar larvae were collected 24–36 hours before pupariation. Mutant larvae that failed to pupate were timed according to the development of their heterozygous siblings. Gut color, mouth hook and spiracle morphology, and the size and morphology of the brain and discs served as additional controls for developmental staging.

The genetic screen was based on the mild haplo-insufficient phenotype of Zfrp8null/+ larvae. The lymph gland of Zfrp8null/+ larvae is on average twice (2.1; SD = 0.2) as large as that of wild type. Second and third chromosome deficiencies were crossed to T(2;3)B3, CyO; TM6B, Tb1 balancers and then crossed with Zfrp8null /T(2;3)B3, CyO. From each cross, 10–30 trans-heterozygous, non-Tb larvae at the late third-instar stage were dissected, the area of 2D images of sample lymph glands were measured using Adobe PhotoShop and normalized to the size of the wild-type gland as previously described (Minakhina et al. 2007).

Immunochemistry and imaging

Larval lymph glands were dissected, fixed, immunostained, and analyzed as described previously (Jung et al. 2005; Minakhina and Steward 2010; Minakhina et al. 2011). Antibodies specific for plasmatocytes (P1, 1:400 dilution; from Dr. I. Ando, Biological Research Center, Szeged, Hungary); rabbit anti-PPO2 antibody (1:2000; from Dr. G. Christophides, Imperial College, London); rabbit anti-Pxn antibody (1:700; from Drs. John Fessler and Sergey Sinenko, UCLA); and anti-Antp antibody (1:20; from Glicksman and D. Brower, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) were used as plasmatocyte, crystal cells, CZ prohemocyte, and PSC markers, respectively (Christophides et al. 2002; Kurucz et al. 2007a, b; Nelson et al. 1994). Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to visualize cell shape and detect lamellocytes. Secondary goat anti-mouse Cy3 and goat anti-rabbit Cy5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) were used at 1:500. DNA was stained using Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and examined with a Zeiss Axioplan-2 microscope. Images were captured using a Leica DM IRBE laser scanning confocal microscope (objectives 40× and 63× oil), analyzed with Leica Microsystems software, and further processed using Adobe PhotoShop.

RESULTS

To find genetic interactors of Zfrp8 and identify novel genes functioning in hematopoiesis, we performed a dominant modifier screen. We took advantage of the dominant phenotype of Zfrp8null /+ larvae, whose lymph glands are 2.1 (SD = 0.2) times larger than wild type, and a series of chromosomal deficiency lines (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) that uncover more than half of the genome. Two-hundred eighty-eight second and third chromosomal deficiencies (Table 1 and Table S1) were crossed with Zfrp8null/T(2:3)Cy, Tb to obtain Df +/+ Zfrp8null or Zfrp8null/+, Df/+ larvae. Then 10–30 trans-heterozygous late third-instar larvae from each cross were dissected and the size of the lymph glands assessed [see Materials and Methods and Minakhina et al. (2007)]. When more than half of the lymph glands were in the range of 0.8–1.2 times the size of the wild-type gland (average size of all glands 1–1.3; SD < 0.3), the deficiency was classified as a strong suppressor (Table 1). Weak modifiers that altered the average size of the Zfrp8/+ lymph gland in fewer than half of the animals and showed variations in shape or size are listed in Table S1. The majority of deficiencies tested (190) in trans to Zfrp8null show no difference from Zfrp8null /+ lymph gland phenotype (Table S1).

We identified 18 deficiencies that strongly suppress the Zfrp8null /+ lymph gland overgrowth. The morphology of the lymph gland of these heterozygous deficiencies was also analyzed in a Zfrp8+ background. Three deletions produced smaller lymph glands than normal in heterozygous animals (“Zfrp8-independent phenotypes”; Table 1). The other 15 deletions caused no or a moderate enlargement (from 1.2 to 1.7 the wild-type size) of the lymph gland (see “Suppressing” in Table 1, column 1).

We also identified 13 deficiencies that changed the shape of Zfrp8null/+ lymph glands (more than half of the glands show severe reproducible changes). These changes included loss of the petal-shaped CZ (Figure 1F), altered CZ shapes (Figure 1G), lymph gland disintegration (Figure 1, D and E), and primary or secondary lobe enlargement. When crossed to wild type, 7 of them showed the same morphological changes as observed in trans to Zfrp8 and were placed into the “Zfrp8-independent” group (Table 1). The other 6 deficiencies showed a phenotype only in trans to Zfrp8null and showed normal morphology in a wild-type background. They formed a group called “modifying deficiencies” (Table 1). This group also included Df(3L)W10, which caused lethality of trans-heterozygotes (Zfrp8null/+, Df(3L)W10/+).

Smaller and partially overlapping deficiencies in 12 of the 32 chromosomal regions were checked for their ability to modify the Zfrp8null/+ phenotype. Smaller deletions in regions 23E–23F and 59B–59E showed no phenotypic change in trans to Zfrp8null. From the other 10 chromosomal regions, each uncovering from 5 to 150 genes, we chose 41 genes that had available mutant alleles (Table 2). Priority was given to genes that did not have an established function in Drosophila hematopoiesis. Lymph glands of trans-heterozygous Zfrp8null larvae were scored as above. Smaller deficiencies uncovering the segment deleted in Df(3L)W10 did not allow us to identify the region responsible for the lethality. However, one of the deletions, Df(3L)ED4710, showed enlargement of the Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland: 9 of 16 lymph glands were 3.5 to 4 times larger than wild type.

Dominant suppressors of Zfrp8 regulate hemocyte differentiation

The screen for dominant modifiers identified both known and novel genes involved in Drosophila hematopoiesis and immunity. For example, smoothened (smo) and adenosine deaminase growth factor (Adgf-A) were known to function in the development of hemocytes, and signal peptide protease (spp) is known to regulate Drosophila immunity (Dolezal et al. 2005; Junell et al. 2007; Tokusumi et al. 2010). But the nine genes [pelota (pelo), hoi-polloi (hoip), mutagen-sensitive 304 (mus304), SHC-adaptor protein (Shc), visgun (vsg), phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (Pdk1)/Pk61C, ecdysone-induced protein 75B (Eip75B), CG30415, and lethal (2) giant larvae (l(2)gl)] did not have an established function in hematopoiesis. To determine a possible hematopoietic function of these genes, we analyzed the lymph gland phenotypes of homozygous mutant larvae at early middle and late third-instar stages using specific markers for terminal hemocyte maturation. We used P1 antibody staining the plasmatocyte-specific protein Nimrod C1 (Kurucz et al. 2007a), anti-Pro-phenoloxidase for crystal cells (Christophides et al. 2002; De Gregorio et al. 2002), phalloidin to reveal the shape of lamellocytes, and anti-Pxn to define the CZ (Figures 2–4) (Jung et al. 2005; Nelson et al. 1994). Homozygotes of the suppressing genes hoip (hoipk07104) and Pdk1/Pk61C (Pk61CEP3091) showed early lethality and were excluded from this analysis. Lymph glands of middle and late third-instar Adgf-A, vsg, shc, and CG30415 homozygous larvae were compared with wild-type lymph glands at similar stages of development (Figure 2).

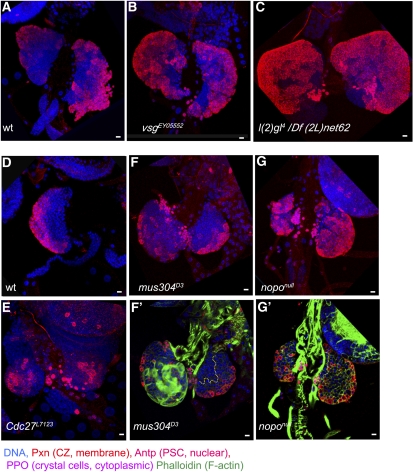

Figure 4 .

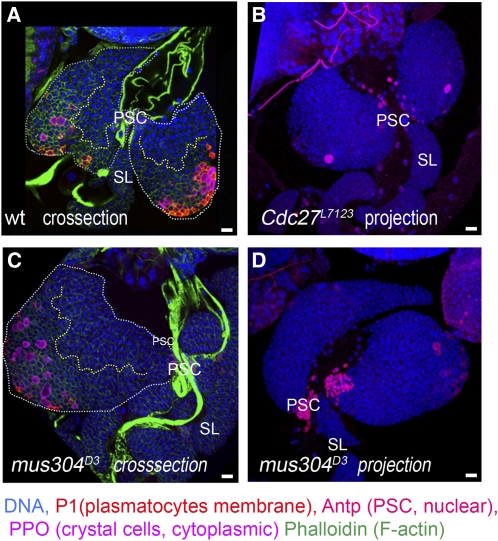

Lymph gland differentiation in mus304 and cdc27 mutants Confocal cross-sections (A, C) and projections (B, D) of wild type (A), Cdc27L7123 (B), and mus304D3 (C, D) middle-late third-instar larval lymph glands. Mutant lymph glands show some delay in plasmatocyte differentiation (P1, membrane marker, red). mus304D3 lymph glands show variations in size and differentiation (C, D). PSCs are stained with anti-Antp (nuclear red). DNA is shown in blue. (A, C) The primary lobes are outlined by white dotted line, and the border between MZ and CZ is shown by yellow dotted line; staining with phalloidin (green in A, C) allows detection of lamellocytes. Scale bars are 10 μm.

During normal development, the crystal cells can be detected in the CZ throughout the third-instar larval stages. Lamellocytes are only occasionally seen in late third-instar larval lymph glands. The Nimrod C1 (P1)-positive plasmatocytes are not seen in the lymph glands until the middle of third instar. During late third-instar larval development, plasmatocyte differentiation starts on the surface of the CZ, whereas the hemocytes in the inner layers of the CZ differentiate later during metamorphosis (Figures 1C and 2F) (Grigorian et al. 2011; Minakhina et al. 2011).

Adgf-A controls deamination of adenosine and deoxyadenosine. Complete loss of Adgf-A causes a dramatic increase in levels of adenosine and deoxyadenosine in larval hemolymph. It also leads to increased numbers of circulating hemocytes, disintegration of the lymph gland primary lobe, a large number of cells with characteristics of plasmatocytes and macrophages, and larval death (Dolezal et al. 2005). We found that a hypomorphic allele, Adgf-Ad11616, caused by a P-element insertion into the first intron, did not affect viability but caused a strong hematopoietic phenotype (Figure 2, B, B′, and G). Plasmatocyte differentiation starts prematurely in early third-instar larvae, and by the late third-instar stage, the majority of cortical prohemocytes, including the hemocytes in the inner layers of the gland, were positive for the plasmatocyte marker. The size of the medulla was significantly reduced compared with wild type (Figure 2G).

Vsg is an ortholog of mammalian sialomucin endolyn (CD164), an adhesion receptor protein that regulates the adhesion of CD34+ stem or precursor cells to bone marrow stroma and the recruitment of CD34+ cells into mitosis (Chan et al. 2001; Forde et al. 2007). In Drosophila, all existing loss of function alleles are homozygous viable. Although ablation of Vsg inhibits proliferation in S2 cells and loss-of-function mutations cause some reduction in embryonic viability, it seems otherwise not to be required for animal development and fecundity (Zhou et al. 2006). The function of vsg in Drosophila hematopoiesis or immune response has not been previously studied. We tested the phenotypes of two P-element alleles, hypomorphic vsgEY0552 and complete loss-of-function vsgBG00708. Both alleles showed increased plasmatocyte differentiation, detectible in early-to-middle third-instar larvae, and by late third instar, the majority of cortical cells expressed the plasmatocyte marker (P1, membrane red in Figure 2, C, C′, and H). In the mutants, the size of the MZ was decreased, whereas the CZ became relatively enlarged (Figures 2H and 3B). These results suggest that, similar to mammalian Endolin, Drosophila Vsg has a blood-specific function: it controls homeostasis between MZ and CZ and inhibits premature plasmatocyte maturation.

Figure 3 .

Changes in MZ-CZ organization in mutant lymph glands. Confocal projections of late third-instar lymph glands of wild type (A), vsgEY05552 (B) homozygous mutants, and l(2)gl4 Df(2L)net62 (C). The relative size of the CZ (anti-Pxn, membrane-cytoplasmic, red) in both mutants is increased, whereas the MZ (Pxn-negative) size is decreased. Severe reduction of the MZ is also seen in early middle third-instar noponull lymph glands (G, G′) compared with wild-type lymph glands at the same stage (D). In Cdc27L7123 and mus304D3 mutants (E, F) the relative sizes of MZ and CZ are not significantly changed. Staining with phalloidin (green) shows the burst of lamellocytes in cross-sections through the inner lymph gland layers (F′, G′) in one lobe of mus304D3. Yellow dotted line separates MZ and CZ in (F′, G′). PSCs are stained with anti-Antp (nuclear red). DNA is shown in blue. Scale bars are 10 μm.

Shc is a conserved adaptor protein implicated in several signaling pathways (RAS-MAPK, EGFR, PDGFR, TrkA) (Bonati et al. 2000; Hallberg et al. 1998; Lunghi et al. 2001; Luschnig et al. 2000). In humans, Shc is highly enriched in primary acute myeloid leukemia blasts (Bonati et al. 2000; Lunghi et al. 2001). In Drosophila, mutations in shc are semi-lethal and sterile, but the function of the gene in hematopoiesis has not been studied (Luschnig et al. 2000). We found that a viable P-element insertion in the 5′-UTR of shc led to premature plasmatocyte differentiation seen in middle third-instar lymph glands (Figure 2, D and D′).

CG30415 encodes the least-conserved protein that we obtained in our screen, and its function is not known. A P-element insertion into the 3′-UTR of CG30415 (CG30415EY04039) causes a strong increase in plasmatocyte differentiation, leading to early disintegration of the primary lymph gland lobes and overgrowth and differentiation of the secondary lobes (Figure 2I).

l(2)gl encodes a component of the Par (partitioning defective) complex and is required for asymmetric cell division and establishment of epithelial cell polarity (Ohshiro et al. 2000; Peng et al. 2000). At the end of the third instar, l(2)gl4/Df(2L)net62 larvae develop tumors in the brain and imaginal discs (Mechler et al. 1985). These mutant larvae do not enter pupation. We noticed that lymph glands also undergo strong overgrowth, up to 20–30 times depending on the age of the larva. To standardize our investigations, we analyzed the lymph gland phenotypes of homozygous mutants, heterozygous siblings, and wild-type larvae of the same age (see Materials and Methods). In the mutants, the lymph gland enlargement was already seen after the second molt in early third-instar larvae when the tumors in other tissues were not apparent. The CZ of the gland was significantly expanded, but it showed more variation in size and differentiation than other mutants (Figures 2, E, E′, and J, and 3C). The lymph glands in heterozygous l(2)gl4/+ larvae were also slightly enlarged (not shown).

Enhancers of the Zfrp8/+ phenotype

In our screen, we identified two enhancers of Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth: smo and mus304 in trans to Zfrp8null caused substantial increase of the lymph gland size (more than four times wild-type size). A similar phenotype was previously observed in Zfrp8null/+; Cdc27 L7123/+ animals (Minakhina et al. 2007).

Smo is a 7-transmembrane G-like protein-coupled receptor, an essential component of the Hh pathway known to control prohemocyte homeostasis (Mandal et al. 2007; Tokusumi et al. 2010). The homozygous smo3 phenotype could not been studied because of early larval lethality. Heterozygous smo3/+ larvae did not show lymph gland enlargement (data not shown). The study of this gene will have to be done in combination with other pathway players and will provide better understanding of the role of Hh signaling in hematopoiesis.

Mus304 is involved in the mitotic cell cycle, DNA repair, and the DNA damage checkpoint (Bi et al. 2005; Boyd et al. 1981; Brodsky et al. 2000). Both alleles tested, mus304D1 and mus304D3 in trans to Zfrp8null, lead to lymph gland enlargement of up to four times that of wild type. mus304D3 is a homozygous viable allele that shows sensitivity to mutagens, defects in DNA repair, and telomere maintenance (Bi et al. 2005; Boyd et al. 1981; Brodsky et al. 2000). About half (9 of 14 tested) of the mus304D3 animals show lymph gland enlargement (Figure 4, B and C), which was often accompanied (6 of 9) by lamellocyte over-differentiation in one or both primary lobes (Figure 3, F and F′). No consistent changes in medulla-cortex organization, plasmatocyte, or crystal cell differentiation were observed (Figure 4, C and D). The overgrowth and occasional lamellocyte differentiation may reflect an immune reaction to increased numbers of cells dying from unrepaired spontaneous DNA damage. In addition, some increase in cell proliferation may result from the lack of a mitotic checkpoint.

Cdc27, a previously identified enhancer of Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth, also encodes a cell-cycle protein and regulates the spindle checkpoint (Deak et al. 2003; Minakhina et al. 2007). Mutation in Cdc27 (Cdc27L71123) caused a modest reduction in differentiation and no visible change in growth (Figures 3E and 4B).

Identification of genes functioning in lymph gland development using conditional knockdown

No mutations were available for a large number of genes uncovered by the Zfrp8-interacting deficiencies. To test their function in hematopoiesis, we obtained UAS-dsRNA (RNAi) lines (VDRC or TRiP; Table 2) for 30 genes from seven interacting regions. Using the hemocyte-specific driver pxn-GAL4, we knocked down each gene in the CZ of the lymph gland and assessed the resulting phenotypes. For about half of the lines, we also utilized a general driver, tubulin (tub)-Gal4, and dome-GAL4, a driver expressed in embryos, some larval tissues, and highly expressed in most MZ cells. Few dome-positive cells are also found in the CZ transition zone (Sinenko et al. 2009). This zone is notably enlarged in Zfrp8null/+ lymph glands, and mitotically active CZ prohemocytes are intermingled with dome-positive cells [see Figure 5Q and Minakhina et al. (2007)].

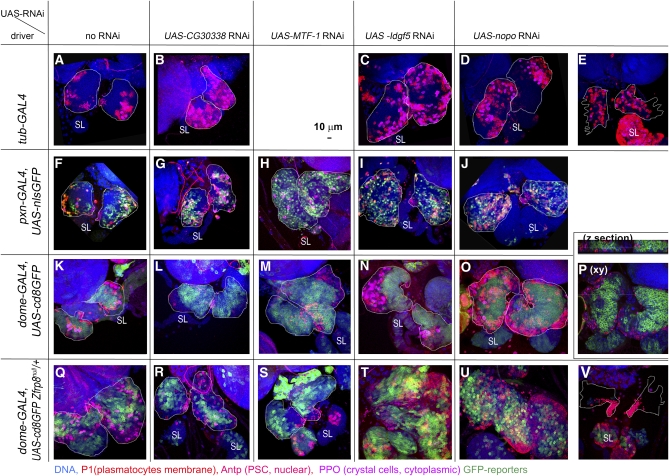

Figure 5 .

Knockdown phenotypes of Zfrp8 modifiers. Confocal projections of lymph glands obtained from the crosses of the three drivers [tub-GAL4 (A–E); pxn-GAL4,2XUAS-nlsGFP (CZ cells, nuclear green, F–J), and dome-GAL4, UAS-cd8GFP (MZ cells, membrane green, K–P)] to UAS-RNAi lines of CG30338 (B, G, L, R), MTF-1 (H, M, S), Idlg5 (C, I, N, T), and nopo (D, E, J, O, P, U, V). Drivers crossed with wild type (A, F, K) show normal MZ-CZ organization and hemocyte differentiation. (Q) dome-GAL4, UAS-cd8GFP combined with heterozygous Zfrp8null shows lymph gland enlargement, similar to that of Zfrp8null/+, and increase in dome-positive cells intermingled with CZ prohemocytes. The lymph gland overgrowth is suppressed when CG30338 (R) or MTF-1 (S) are knocked down in MZ, whereas overgrowth is enhanced when Idgf5 (T) or nopo (V) are depleted. nopo knockdown in trans to Zfrp8null/+ also causes disintegration of primary lobes in late third-instar larvae (V). Primary lobes (outlined by white dotted line) are identified by their anterior position and presence of PSC (anti-Antp, nuclear red). Secondary lobes (SL) show excessive growth and differentiation in most nopo knockdown lymph glands (E, J, U, V). Plasmatocytes are stained with P1 antibody (membrane, red) and crystal cells with anti-PPO2 (cytoplasmic, pink). DNA is shown in blue. Scale bar is 10 μm.

The majority of the RNAi lines used in this study caused no or a variable lymph gland phenotype when expressed under the control of pxn-Gal4. For several genes, the strong effect of the knockdown in the CZ correlated with the general function of the gene in cell metabolism or cell survival. For instance, knockdown of RpL31 by pxn-GAL4 resulted in disintegration of the CZ and hemocyte death. General knockdown of RpL31 by tub-GAL4 caused growth arrest and early larval lethality. Similarly, CG3911 and Not1 RNAi expression both caused early lethality when generally expressed (tub-GAL4) and showed vast reduction in numbers of CZ cells when driven by pxn-GAL4 (not shown).

We selected four lines that triggered reproducible changes in lymph gland development and also modified the Zfrp8null/+ phenotype (Figure 5) for further study. CG30338 and metal response element-binding transcription factor-1 (MTF-1) suppressed Zfrp8null/+ overgrowth (Figure 5, Q–S), whereas knockdown of imaginal disc growth factor 5 (Idgf5) and no-poles (nopo) enhanced the overgrowth and led to premature primary lobe disintegration in late third-instar larvae (Figure 5, T–V). Individual knockdown of each gene caused distinct abnormalities in lymph gland development.

CG30338 encodes an uncharacterized conserved protein, a putative ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme with DUF1115 and RWD domains (Flybase annotation; Tweedie et al. 2009). Animals with general depletion of CG30338 (tub-GAL4) survived until adulthood. The larval lymph glands were smaller and contained increased numbers of plasmatocytes and crystal cells (Figure 5B). When CG30338 was knocked down in CZ by pxn-GAL4 or in MZ by dome-GAL4, no increase in differentiation was observed. Interestingly, half of the dome-GAL4, UAS-CG30338 RNAi animals showed fewer differentiated cells within the lymph gland CZ than controls (Figure 5, F, G, K, and L). When CG30338 was knocked down by dome-GAL4 in Zfrp8null /+ larvae, the lymph glands appeared smaller than in Zfrp8null /+ animals and showed similar levels of differentiation as the driver control (dome-GAL4, UAS-cd8GFP; Figure 5, K, Q, and R). Thus, CG30338 appears to control hemocyte maturation.

MTF-1 encodes a zinc finger protein that is conserved from insects to mammals. In response to heavy metals, it activates a set of metallothionine genes (Egli et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2001). Knockdown of the gene by tub-GAL4 affected larval growth and led to lethality during the third instar. The lymph glands of these ailing larvae were excluded from analysis. Gene knockdown by dome-Gal4 or pxn-GAL4 did not alter larval growth and viability. The lymph glands of these larvae showed an increase in size (from 1.2 to 1.7 of wild-type size) and relatively low levels of differentiation (Figure 5, H, M, and S). In all 12 pxn-GAL4, UAS-MTF-1-RNAi lymph glands, we observed very few differentiated plasmatocytes, suggesting that MTF-1 may specifically regulate plasmatocyte differentiation during normal hematopoiesis.

Idgf5 has chitinase and growth factor activity and is found in the larval hemolymph (Karlsson et al. 2004; Kawamura et al. 1999), but its role in hematopoiesis, wound healing, and immune response is unclear. When Idgf5 RNAi was driven by tub-GAL4 or dome-GAL4, the lymph gland was ∼2 times enlarged and the number of crystal cells was strongly increased (Figure 5, C and N). Knockdown of the gene at later stages of hemocyte development (pxn-GAL4) did not increase the number of crystal cells; rather, there were fewer differentiated hemocytes than in controls, and in the same glands, the MZ was visibly smaller (Figure 5I). These results suggest that Idgf5 may function early in nondifferentiated hemocytes to regulate their fate. The expression of Idgf5 RNAi under the control of dome-Gal4 resulted in strong enhancement of the Zfrp8null /+ phenotype with increase in the size of the MZ and transition zone (green in Figure 5T). Whether the change of hemocyte fate can cause an overgrowth in sensitized Zfrp8null/+ lymph glands remains unclear.

Nopo is a maternal effect cell-cycle regulator and encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase (Merkle et al. 2009). Knockdown of the gene by three different drivers leads to three different lymph gland phenotypes. General knockdown with tub-GAL4 caused increase in differentiation and premature disintegration of the primary lobes (Figure 5, D and E). Similar to what is observed with Idgf5 RNAi, expression of nopo RNAi in CZ (pxn-GAL4) caused a decrease of the MZ in late third-instar lymph glands without a severe increase in differentiation. When the gene was downregulated in the MZ (dome-GAL4), the MZ was not diminished but the medulla-cortex spatial organization was altered. The gland became more spherical in shape, and the cortical zone covered the surface of the entire gland instead of forming a distal petal-shaped structure (Figure 5, N–P). Knockdown of nopo by dome-GAL4 in combination with loss of one copy of Zfrp8 led to gland overgrowth, followed by disintegration of the primary lobes and premature differentiation of cells in the secondary lobe (Figure 5, U and V).

General knockdown of the gene caused great reduction in larval viability, whereas existing nopo mutations are viable and sterile (Merkle et al. 2009). We analyzed the lymph gland phenotypes of two mutant alleles, nopoEXC142 and nopo Z1447. In nopoEXC142, part of the 5′-UTR and the exons encoding amino acids 1–181 are deleted, and it is therefore considered a null allele; nopoZ1447 is an E11K missense mutation (Merkle et al. 2009). Lymph gland development in both mutant alleles was similar. The primary lobes were 3–5 times enlarged and had substantially increased numbers of plasmatocytes and crystal cells (Figure 6, B and C). The size of the MZ was greatly reduced (Figures 3, G and G′, and 6B). In second- and early third-instar larvae, the MZ was represented by a narrow strip of cells adjacent to the pericardial cells along the dorsal vessel (Figure 3G′), and during the third-instar larval stage, it was barely half the size of the wild-type MZ (Figure 6B). The mutants also showed an increase in crystal cell numbers. To test if the increase in mature crystal cells (PPO-positive) correlates with an increase in crystal-cell precursors, we stained the wild-type and mutant lymph glands for the early crystal cell marker Lz. In wild type, Lz-positive cells were relatively densely packed in the CZ of middle third-instar lymph glands. In nopo mutants of the same age, the CZ was greatly enlarged, and Lz-positive cells were found in a similar density all over the CZ (Figure 6, D–E′). The increase in mature crystal cells in nopo mutants correlated with CZ enlargement and overall early blood cell maturation within the CZ (Figure 6B). Mutant and knockdown phenotypes suggest that nopo controls homeostasis between the hematopoietic precursors in the MZ, and the prohemocytes and mature blood cells in the CZ.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of Zfrp8 mutant clones in the lymph gland show that it is required in HSCs but is dispensable at later stages of hemocyte proliferation or differentiation. But Zfrp8 mutants have vast lymph gland overgrowth (Minakhina et al. 2007; Minakhina and Steward 2010). In the mutant lymph glands, all hemocytes rapidly proceed to the stage of differentiation corresponding to wild-type CZ prohemocytes, the most mitotically active stage during hemocyte development (Jung et al. 2005; Krzemien et al. 2010; Minakhina and Steward 2010). Therefore, it is the loss of HSCs in the mutant animals that ultimately leads to lymph gland overgrowth and severe change in hemocyte homeostasis. Interestingly, the loss of one copy of the gene also affects hemocyte development, leading to noticeable lymph gland enlargement (Minakhina et al. 2007). In our previous screen for candidate modifiers of Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth, we identified two cell-cycle regulators and one novel gene, pnr, required for plasmatocyte differentiation (Minakhina et al. 2007, 2011). Hence, we hypothesized that two major groups of factors contribute to the Zfrp8 lymph gland phenotype, direct regulators of the cell cycle, and factors controlling hemocyte differentiation.

In the past, several genetic screens in other laboratories were designed to detect regulators of cellular immune response, hemocyte activation, and melanotic mass formation (Avet-Rochex et al. 2010; Milchanowski et al. 2004; Rodriguez et al. 1996; Zettervall et al. 2004). The majority of the genes identified in these screens regulate lamellocyte and crystal cell development. Our present genetic screen yielded a number of new genes involved in hemocyte differentiation, particularly of plasmatocytes. The lack of significant overlap between all screens can be explained by the difference in screen designs. It also suggests that many hematopoietic genes have not been identified so far. For instance, a recent RNAi screen by Avet-Rochex et al. (2010) targeting about 10% of Drosophila genes identified 59 hematopoietic factors, 55 of which were not previously linked to blood cell development.

In our screen, we identified 10 deficiencies that had dominant lymph gland phenotypes both in a wild-type background and in trans to Zfrp8null and 21 deficiencies that modified the Zfrp8null/+ phenotype but did not show lymph gland abnormalities in a wild-type background. We tested ∼15% of the genes uncovered by 9 modifying deficiencies and identified 16 suppressors and enhancers of Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth. For 9 of these genes, we showed a new role in the regulation of blood cell development.

Our screen also suggested that the number of uncharacterized genes regulating different aspects of hematopoiesis is much larger than the number of genes identified so far. This conclusion is supported by the following observation: we characterized half of interacting deficiencies and many of them uncover two or more modifying genes. For instance, in two chromosomal regions (30C5 and 67A2–D12), we found four dominant suppressors, pelo, hoip, shc, and vsg. Other two modifying deficiencies, Df(3L)W10 and DF(2L)net-PMF, contained both enhancers and suppressors (see Table 1).

Of the four enhancers identified in the screen, two, mus304 and nopo, function in the DNA-damage response and cell-cycle regulation. A previously identified enhancer of Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth, Cdc27, also encodes a cell-cycle protein that regulates the spindle checkpoint (Deak et al. 2003; Minakhina et al. 2007). Analysis of homozygous mutant phenotypes of individual genes has shown that each of the three genes triggered different changes in lymph gland development. Mutation in Cdc27 caused modest decrease in growth and differentiation (Figures 3E and 4B), and mus304 prompted moderate overgrowth and high incidence of lamellocyte differentiation in one or more lobes (Figures 3, F and F′, and 4, C and D). Mutations in nopo and nopo gene knockdown had complex effects on lymph gland development, including noticeable overgrowth, MZ reduction, and increase in crystal cells (Figures 5 and 6). None of the three genes had a dominant phenotype, and all of them enhanced Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth. These genes may function together with Zfrp8 in regulating HSC division. Alternatively, their dominant effects on cell-cycle timing may become only evident in the Zfrp8null/+ background, in which the population of mitotically active CZ prohemocytes is increased.

The majority of dominant modifiers identified in the screen suppressed the Zfrp8null/+ lymph gland overgrowth. We analyzed homozygous phenotypes of five of the nine suppressing genes, and all represented different molecular pathways. With the exception of l(2)gl, they all had a similar effect on hemocyte differentiation. Homozygous loss-of-function mutants induced early plasmatocyte differentiation and changed the balance between the CZ and MZ (Figures 2 and 3). Three of the genes, AdgfA, vsg, and Shc, are highly conserved across species, but only AdgfA was previously reported to function in Drosophila hematopoiesis (Dolezal et al. 2005). Interestingly, human homologs of both Vsg and Shc are differentially expressed in hematopoietic progenitors and leukemic cells (Chan et al. 2001; Forde et al. 2007; Fukuda et al. 2011; Lunghi et al. 2001). The mammalian Vsg ortholog, endolyn (CD164), regulates the interaction of hematopoietic stem and precursor cells with the niche and their adhesion and migration (Forde et al. 2007). Drosophila Vsg is required for homeostasis between precursor cells and differentiated hemocytes, a process that also depends on niche signaling.

Using RNAi-mediated conditional gene knockdown, we identified four new genes functioning in Drosophila hematopoiesis. Three of them may have similar functions in vertebrates. We found that MTF-1 is required for plasmatocyte development in the Drosophila lymph gland, whereas its mouse homolog is known to play a critical role in lymphocyte development (Wang et al. 2004). The second gene, nopo, affects early embryonic development (Merkle et al. 2009), and in our experiments, it shows a striking lymph gland phenotype but does not affect other somatic tissues. It has been suggested that lack of Nopo may change the timing of the S-M transition and lead to acentrosomal or mis-oriented spindles (Merkle et al. 2009). The development of lymph glands may be particularly sensitive to these defects. However Nopo may also function in ubiquitination of non-cell-cycle–related, blood-cell–specific targets. Nopo is one of about 130 E3 ubiquitin ligases encoded in the Drosophila genome (Merkle et al. 2009), and its mammalian orthologs, such as c-Cbl, Fbw7, Triad1, and FLRF (Rnf41), are implicated in normal and malignant hematopoiesis (Jing et al. 2008; Kitagawa et al. 2009; Marteijn et al. 2009; Rathinam et al. 2008; Reavie et al. 2010). The third conserved gene, CG30338, encodes a predicted ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, another component of ubiquitination pathway. It is the least-studied gene, and its interesting hematopoietic phenotype in flies and the conserved structure of the protein across species warrants future investigation.

Most mutations identified in this screen caused distinct abnormalities in hemocyte differentiation, but none resulted in complete loss or enlargement of the MZ, suggesting that early stages of hematopoiesis were least affected. Given that Zfrp8 is required already in the embryo in HSCs and that the overgrowth is a consequence of this early lymph gland abnormality, it is not surprising that we obtained an array of genes functioning at different points of hematopoiesis later in development, affecting a number of conserved molecular pathways. Our results show that the similarities between mechanisms of regulation of hematopoiesis in flies and mammals extend beyond transcriptional regulation, and hence, Drosophila serves as an excellent model for identification and study of genes functioning in growth control, cell cycle, and cell differentiation in hematopoiesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ruth Steward for support; Istvan Ando, Utpal Banerjee, Kenneth Irvine, Laura Lee, George Christophides, and Sergey Sinenko for fly stocks and antibodies; and Sarah Radford for reading and commenting on the manuscript. We thank William Tan, Neha Changela, and Kritika Jawdekar for help with the genetic experiments and Le Nguyen for help with stocks and fly food. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NIHD018055 and by the Goldsmith Foundation.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: S. L. Forsburg

Literature Cited

- Avet-Rochex A., Boyer K., Polesello C., Gobert V., Osman D., et al. , 2010. An in vivo RNA interference screen identifies gene networks controlling Drosophila melanogaster blood cell homeostasis. BMC Dev. Biol. 10: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baou M., Norton J. D., Murphy J. J., 2011. AU-rich RNA binding proteins in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Blood 118: 5732–5740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi X., Srikanta D., Fanti L., Pimpinelli S., Badugu R., et al. , 2005. Drosophila ATM and ATR checkpoint kinases control partially redundant pathways for telomere maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 15167–15172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonati A., Carlo-Stella C., Lunghi P., Albertini R., Pinelli S., et al. , 2000. Selective expression and constitutive phosphorylation of SHC proteins [corrected] in the CD34+ fraction of chronic myelogenous leukemias. Cancer Res. 60: 728–732 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J. B., Golino M. D., Shaw K. E., Osgood C. J., Green M. M., 1981. Third-chromosome mutagen-sensitive mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 97: 607–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky M. H., Sekelsky J. J., Tsang G., Hawley R. S., Rubin G. M., 2000. mus304 encodes a novel DNA damage checkpoint protein required during Drosophila development. Genes Dev. 14: 666–678 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. Y., Lee-Prudhoe J. E., Jorgensen B., Ihrke G., Doyonnas R., et al. , 2001. Relationship between novel isoforms, functionally important domains, and subcellular distribution of CD164/endolyn. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 2139–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophides G. K., Zdobnov E., Barillas-Mury C., Birney E., Blandin S., et al. , 2002. Immunity-related genes and gene families in Anopheles gambiae. Science 298: 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozatier M., Meister M., 2007. Drosophila haematopoiesis. Cell. Microbiol. 9: 1117–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gregorio E., Han S. J., Lee W. J., Baek M. J., Osaki T., et al. , 2002. An immune-responsive Serpin regulates the melanization cascade in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 3: 581–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak P., Donaldson M., Glover D. M., 2003. Mutations in makos, a Drosophila gene encoding the Cdc27 subunit of the anaphase promoting complex, enhance centrosomal defects in polo and are suppressed by mutations in twins/aar, which encodes a regulatory subunit of PP2A. J. Cell Sci. 116: 4147–4158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G., Chen D., Schnorrer F., Su K. C., Barinova Y., et al. , 2007. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 448: 151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal T., Dolezelova E., Zurovec M., Bryant P. J., 2005. A role for adenosine deaminase in Drosophila larval development. PLoS Biol. 3: e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli D., Selvaraj A., Yepiskoposyan H., Zhang B., Hafen E., et al. , 2003. Knockout of ‘metal-responsive transcription factor’ MTF-1 in Drosophila by homologous recombination reveals its central role in heavy metal homeostasis. EMBO J. 22: 100–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. J., Banerjee U., 2003. Transcriptional regulation of hematopoiesis in Drosophila. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 30: 223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde S., Tye B. J., Newey S. E., Roubelakis M., Smythe J., et al. , 2007. Endolyn (CD164) modulates the CXCL12-mediated migration of umbilical cord blood CD133+ cells. Blood 109: 1825–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S., Abe M., Onishi C., Taketani T., Purevsuren J., et al. , 2011. Survivin selectively modulates genes deregulated in human leukemia stem cells. J. Oncol. 2011: 946936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorian M., Mandal L., Hartenstein V., 2011. Hematopoiesis at the onset of metamorphosis: terminal differentiation and dissociation of the Drosophila lymph gland. Dev. Genes Evol. 221: 121–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg B., Ashcroft M., Loeb D. M., Kaplan D. R., Downward J., 1998. Nerve growth factor induced stimulation of Ras requires Trk interaction with Shc but does not involve phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase. Oncogene 17: 691–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing X., Infante J., Nachtman R. G., Jurecic R., 2008. E3 ligase FLRF (Rnf41) regulates differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors by governing steady-state levels of cytokine and retinoic acid receptors. Exp. Hematol. 36: 1110–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junell A., Uvell H., Pick L., Engstrom Y., 2007. Isolation of regulators of Drosophila immune defense genes by a double interaction screen in yeast. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37: 202–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S. H., Evans C. J., Uemura C., Banerjee U., 2005. The Drosophila lymph gland as a developmental model of hematopoiesis. Development 132: 2521–2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson C., Korayem A. M., Scherfer C., Loseva O., Dushay M. S., et al. , 2004. Proteomic analysis of the Drosophila larval hemolymph clot. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 52033–52041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura K., Shibata T., Saget O., Peel D., Bryant P. J., 1999. A new family of growth factors produced by the fat body and active on Drosophila imaginal disc cells. Development 126: 211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa K., Kotake Y., Kitagawa M., 2009. Ubiquitin-mediated control of oncogene and tumor suppressor gene products. Cancer Sci. 100: 1374–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzemien J., Dubois L., Makki R., Meister M., Vincent A., et al. , 2007. Control of blood cell homeostasis in Drosophila larvae by the posterior signalling centre. Nature 446: 325–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzemien J., Oyallon J., Crozatier M., Vincent A., 2010. Hematopoietic progenitors and hemocyte lineages in the Drosophila lymph gland. Dev. Biol. 346: 310–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz E., Markus R., Zsamboki J., Folkl-Medzihradszky K., Darula Z., et al. , 2007a Nimrod, a putative phagocytosis receptor with EGF repeats in Drosophila plasmatocytes. Curr. Biol. 17: 649–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz E., Vaczi B., Markus R., Laurinyecz B., Vilmos P., et al. , 2007b Definition of Drosophila hemocyte subsets by cell-type specific antigens. Acta Biol. Hung. 58(Suppl.): 95–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanot R., Zachary D., Holder F., Meister M., 2001. Postembryonic hematopoiesis in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 230: 243–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebestky T., Chang T., Hartenstein V., Banerjee U., 2000. Specification of Drosophila hematopoietic lineage by conserved transcription factors. Science 288: 146–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebestky T., Jung S. H., Banerjee U., 2003. A Serrate-expressing signaling center controls Drosophila hematopoiesis. Genes Dev. 17: 348–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunghi P., Tabilio A., Pinelli S., Valmadre G., Ridolo E., et al. , 2001. Expression and activation of SHC/MAP kinase pathway in primary acute myeloid leukemia blasts. Hematol. J. 2: 70–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H., Rose P. E., Roberts T. M., Dearolf C. R., 2002. The Hopscotch Jak kinase requires the Raf pathway to promote blood cell activation and differentiation in Drosophila. Mol. Genet. Genomics 267: 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luschnig S., Krauss J., Bohmann K., Desjeux I., Nusslein-Volhard C., 2000. The Drosophila SHC adaptor protein is required for signaling by a subset of receptor tyrosine kinases. Mol. Cell 5: 231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal L., Banerjee U., Hartenstein V., 2004. Evidence for a fruit fly hemangioblast and similarities between lymph-gland hematopoiesis in fruit fly and mammal aorta-gonadal-mesonephros mesoderm. Nat. Genet. 36: 1019–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal L., Martinez-Agosto J. A., Evans C. J., Hartenstein V., Banerjee U., 2007. A Hedgehog- and Antennapedia-dependent niche maintains Drosophila haematopoietic precursors. Nature 446: 320–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus R., Laurinyecz B., Kurucz E., Honti V., Bajusz I., et al. , 2009. Sessile hemocytes as a hematopoietic compartment in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 4805–4809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteijn J. A., van der Meer L. T., Smit J. J., Noordermeer S. M., Wissink W., et al. , 2009. The ubiquitin ligase Triad1 inhibits myelopoiesis through UbcH7 and Ubc13 interacting domains. Leukemia 23: 1480–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechler B. M., McGinnis W., Gehring W. J., 1985. Molecular cloning of lethal(2)giant larvae, a recessive oncogene of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 4: 1551–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer E. M., Lin Y. C., Murre C., 2011. Factors and networks that underpin early hematopoiesis. Semin. Immunol. 23: 317–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle J. A., Rickmyre J. L., Garg A., Loggins E. B., Jodoin J. N., et al. , 2009. no poles encodes a predicted E3 ubiquitin ligase required for early embryonic development of Drosophila. Development 136: 449–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milchanowski A. B., Henkenius A. L., Narayanan M., Hartenstein V., Banerjee U., 2004. Identification and characterization of genes involved in embryonic crystal cell formation during Drosophila hematopoiesis. Genetics 168: 325–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakhina S., Druzhinina M., Steward R., 2007. Zfrp8, the Drosophila ortholog of PDCD2, functions in lymph gland development and controls cell proliferation. Development 134: 2387–2396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakhina S., Steward R., 2010. Hematopoietic stem cells in Drosophila. Development 137: 27–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakhina S., Tan W., Steward R., 2011. JAK/STAT and the GATA factor Pannier control hemocyte maturation and differentiation in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 352: 308–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee T., Kim W. S., Mandal L., Banerjee U., 2011. Interaction between Notch and Hif-alpha in development and survival of Drosophila blood cells. Science 332: 1210–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratoglu S., Garratt B., Hyman K., Gajewski K., Schulz R. A., et al. , 2006. Regulation of Drosophila friend of GATA gene, u-shaped, during hematopoiesis: a direct role for serpent and lozenge. Dev. Biol. 296: 561–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. E., Fessler L. I., Takagi Y., Blumberg B., Keene D. R., et al. , 1994. Peroxidasin: a novel enzyme-matrix protein of Drosophila development. EMBO J. 13: 3438–3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni J. Q., Zhou R., Czech B., Liu L. P., Holderbaum L., et al. , 2011. A genome-scale shRNA resource for transgenic RNAi in Drosophila. Nat. Methods 8: 405–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novershtern N., Subramanian A., Lawton L. N., Mak R. H., Haining W. N., et al. , 2011. Densely interconnected transcriptional circuits control cell states in human hematopoiesis. Cell 144: 296–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshiro T., Yagami T., Zhang C., Matsuzaki F., 2000. Role of cortical tumour-suppressor proteins in asymmetric division of Drosophila neuroblast. Nature 408: 593–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin S. H., Zon L. I., 2008. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell 132: 631–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C. Y., Manning L., Albertson R., Doe C. Q., 2000. The tumour-suppressor genes lgl and dlg regulate basal protein targeting in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature 408: 596–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam C., Thien C. B., Langdon W. Y., Gu H., Flavell R. A., 2008. The E3 ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl restricts development and functions of hematopoietic stem cells. Genes Dev. 22: 992–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavie L., Della Gatta G., Crusio K., Aranda-Orgilles B., Buckley S. M., et al. , 2010. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cell differentiation by a single ubiquitin ligase-substrate complex. Nat. Immunol. 11: 207–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizki T. M., Rizki R. M., 1992. Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 16: 103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A., Zhou Z., Tang M. L., Meller S., Chen J., et al. , 1996. Identification of immune system and response genes, and novel mutations causing melanotic tumor formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 143: 929–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardina J. L., Lopez-Ruano G., Sanchez-Sanchez B., Llanillo M., Hernandez-Hernandez A., 2011. Reactive oxygen species: Are they important for haematopoiesis? Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. (in press) DOI: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinenko S. A., Mandal L., Martinez-Agosto J. A., Banerjee U., 2009. Dual role of wingless signaling in stem-like hematopoietic precursor maintenance in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 16: 756–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino R. P., Carton Y., Govind S., 2002. Cellular immune response to parasite infection in the Drosophila lymph gland is developmentally regulated. Dev. Biol. 243: 65–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokusumi Y., Tokusumi T., Stoller-Conrad J., Schulz R. A., 2010. Serpent, suppressor of hairless and U-shaped are crucial regulators of hedgehog niche expression and prohemocyte maintenance during Drosophila larval hematopoiesis. Development 137: 3561–3568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweedie S., Ashburner M., Falls K., Leyland P., McQuilton P., et al. , 2009. FlyBase: enhancing Drosophila Gene Ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 37: D555–D559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wimmer U., Lichtlen P., Inderbitzin D., Stieger B., et al. , 2004. Metal-responsive transcription factor-1 (MTF-1) is essential for embryonic liver development and heavy metal detoxification in the adult liver. FASEB J. 18: 1071–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K., Sanada M., Shiraishi Y., Nowak D., Nagata Y., et al. , 2011. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature 478: 64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zettervall C. J., Anderl I., Williams M. J., Palmer R., Kurucz E., et al. , 2004. A directed screen for genes involved in Drosophila blood cell activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 14192–14197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Egli D., Georgiev O., Schaffner W., 2001. The Drosophila homolog of mammalian zinc finger factor MTF-1 activates transcription in response to heavy metals. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 4505–4514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G. Q., Zhang Y., Ferguson D. J., Chen S., Rasmuson-Lestander A., et al. , 2006. The Drosophila ortholog of the endolysosomal membrane protein, endolyn, regulates cell proliferation. J. Cell. Biochem. 99: 1380–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.