Abstract

CXCL12 is a chemotactic cytokine that has pro-metastatic functions in several malignancies through interactions with its receptor, CXCR4. CXCL12 is an estrogen-regulated gene, and notably, estrogen is a major risk factor for endometrial cancer (EC) development. As few studies examine concurrent CXCL12, CXCR4, and estrogen receptor (ER) expression in EC patients, we examined this pathway in 199 EC patients with data from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Cancer Registry. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to detect CXCR4, CXCL12, and ER protein expression. As CXCR4 expression was positive in all cases, this investigation focused on associations between CXCL12 and ER expression, clinicopathologic factors, and survival outcomes using chi-square tests, Kaplan-Meier graphs, and log-rank tests. CXCL12 expression was negative in 63 cases (32%) and positive in 136 cases (68%). Negative CXCL12 expression was borderline significantly associated with metastasis (χ2 p=0.07). ER expression was negative in 75 cases (38%) and positive in 124 cases (62%). Positive ER expression was significantly associated with low grade and early stage tumors (χ2 p<0.001). CXCL12 and ER were not significantly associated (χ2 p=0.11). Positive CXCL12 expression was associated with longer overall survival (OS) (log-rank p=0.006) and longer recurrence-free survival (RFS) (log-rank p=0.01) in ER negative patients, but not in ER positive patients. We identified a unique molecular signature associated with better OS and RFS in EC patients. In addition to pathological characteristics of the tumor, expression of CXCL12 and ER may be clinically useful for assigning adjuvant treatment to EC cases.

Keywords: clear cell, papillary serous, prognostic biomarkers, chemokines, metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. The two major subtypes of EC, Type I and Type II, have different etiologies and survival rates. Type I ECs represent 80%–90% of sporadic tumors and risk factors for this subtype are associated with unopposed estrogen exposure.1, 2 Five-year survival rates for patients with low grade (i.e. well-differentiated) Type I tumors are approximately 90% compared to five-year survival rates between 45% and 77% for patients with high grade (i.e. poorly differentiated) Type I tumors.3–7 The remaining 10%–20% of ECs, Type II, are characterized by invasive disease spread at the time of diagnosis, with survival rates between 50 and 60%.1 Clear cell (CC) and papillary serous (PS) are the two histology subtypes of Type II EC. Although these tumors typically are described as estrogen independent, estrogen receptor (ER) expression has been observed.8–9 Despite being relatively rare, high grade Type I and Type II ECs are clinically important due to their disproportionate mortality.

As high grade Type I, CC, and PS endometrial tumors are characterized by extensive extra-uterine disease at the time of diagnosis, molecular mechanisms related to disease spread are strongly implicated in these subtypes. Previous research suggests that chemokines and their receptors contribute to dissemination of cancer cells from the primary tumor site to local and distant sites.10–12 A commonly studied chemokine ligand-receptor pair, CXCL12/CXCR4, is associated with proliferation, adhesion, and most notably chemotaxis in several malignancies, including breast,13 colon,14 ovarian,15 and pancreatic cancers.16 Muller et al. demonstrated that common sites of metastasis in breast cancer patients (bone, lung, and brain) overexpress CXCL12 while the primary breast tumor is characterized by high levels of CXCR4.13 Improved breast cancer survival is associated with high expression of CXCL12 at the primary site.17–19 Mechanistically, high levels of CXCL12 at the primary tumor site may saturate the receptor and inhibit progression of the tumor beyond the primary site.

The biology of CXCR4, CXCL12, and ER in normal endometrial tissues and EC has been described. In the normal endometrium, CXCR4 gene expression is significantly higher in epithelial cells compared to stromal cells, while CXCL12 is highly expressed in stromal cells and undetectable in normal epithelial cells.20 Compared to normal endometrial tissues, CXCR4 gene expression is significantly higher in EC cell lines and human EC tissues while CXCL12 mRNA is significantly higher in normal endometrial tissues than EC.21 A gradient of ER expression is detectable in normal endometrial tissues and EC, such that expression is generally higher in normal endometrial tissues compared to low grade Type I cancers. Furthermore, ER expression is higher in low grade Type I tumors compared to high grade Type I and Type II tumors, suggesting that lower ER expression is associated with de-differentiation.8, 22

Positive feedback loops between ER and the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis have been reported in breast cancer cell lines, such that activation of ER by estrogen induces CXCL12 gene expression, while CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling also promotes ER transcriptional activation, consequently establishing an autocrine loop for breast cancer cell proliferation.23 This paradigm also may apply to EC. Zhao et al. reported that CXCL12 differentially stimulates growth of EC cells in vitro, dependent on ER and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) expression profiles.24 Low concentrations of CXCL12 stimulated growth of ER positive, PTEN negative EC cells, but not ER negative, PTEN positive EC cells. Furthermore, Kubarek reported that estradiol increased protein expression of CXCR4 and CXCL12 in ER positive but not ER negative EC cells in vitro.25

Despite the evidence supporting a role for the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in EC, only one study has examined the prognostic value of CXCR4 and overall survival (OS) in EC. Patients with CXCR4 positive tumors had a significantly longer OS compared to patients with CXCR4 negative tumors.26 The previous research strongly suggests a prognostic role for CXCL12 and CXCR4 in EC. We investigated the association between CXCL12, CXCR4, and ER expression, clinicopathologic factors, and survival outcomes. Our hypothesis is that higher expression of CXCL12 would be associated with better survival outcomes due to saturation of CXCR4 at the primary site, thus inhibiting migration beyond the uterus.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study sample

The study sample (N=199) was identified through an honest broker system at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Cancer Registry. The sampling frame for this study included 1,486 Type I and Type II EC cases who received all or part of the first course of treatment at Magee-Womens Hospital between 1996 and 2008. Characteristics of this sampling frame have been described previously.27 Demographic, clinical, treatment, and survival information was available for each patient in the sampling frame. Cases were selected for the present study using stratified random sampling. Histology type (Type I and Type II) and stage (stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV) defined the eight sampling strata. Among Type I cases, our sample included 30 stage I, 28 stage II, 36 stage III, and 16 stage IV cases. Among Type II cases, our sample included 36 stage I, 9 stage II, 23 stage III, and 21 stage IV cases. Our goal was to include 25 cases per stratum; however, due to an insufficient number of tumor blocks in certain strata, larger strata were oversampled. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Patients provided written informed consent for archival of tissue samples for future research studies.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded archival tissue samples were retrieved from 199 patients who had a hysterectomy for the treatment of EC at Magee-Womens Hospital between 1996 and 2008. In this study, all tissue material was obtained from the primary tumor; metastatic tissues were not used. Prior to slide sectioning, tissue blocks and matching hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were examined by a gynecologic pathologist to choose tumor regions with sufficient tumor and stromal material. The immunohistochemistry (IHC) protocol began with deparaffinization and rehydration of slide sections with progressively decreasing alcohol concentrations. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% methanol peroxide, antigen was retrieved in 0.01 M boiling citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave, and non-specific staining was blocked with Protein Block (Dako North America, Inc, Carpinteria, California). Whole tissue sections then were incubated for one hour at room temperature with 100 microliters of polyclonal CXCR4 antibody (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, dilution 1:50), polyclonal CXCL12 antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, dilution 1:200), and monoclonal ER antibody (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, pre-diluted). Slides were subsequently rinsed in PBS/Tween solution for five minutes followed by incubation with a polymer (ImmPRESS Universal reagent, Vector Laboratories). Slides were again rinsed in the PBS/Tween solution followed by development with diaminobenzidine for detection. The slides were viewed after being counterstained with Shandon Hematoxylin (Thermo Scientific), rinsed in several concentrations of alcohol solution, and mounted.

To mitigate potential reproducibility problems with the IHC method, we employed the following control measures. First, we followed a standard operating procedure for processing tissues following surgery at Magee-Womens Hospital, which may limit degradation of tissues associated with long fixation times. Second, positive and negative controls were run with each batch of slides, with approximately 40 slides per batch. Normal heart, normal tonsil tissue, and breast cancer tissue were the positive controls for CXCR4, CXCL12, and ER, respectively. The primary antibody was omitted from the negative control slides. Third, optimization of all antibodies and reagents was performed by a trained histology technologist at a highly reputable molecular pathology laboratory. Finally, a random subset of slides were re-stained and reevaluated by the pathologist without knowledge of the previously recorded scores. The intra-rater agreement for the subset of re-stained slides was 100%.

IHC expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4 was classified as negative or positive by an expert gynecologic pathologist blinded to pathologic characteristics and survival outcomes. A case was considered to have positive expression when any cells showed positive staining. Furthermore, tumor and stromal localization was analyzed from a single slide. We observed nuclear and cytoplasmic staining for CXCR4, cytoplasmic and membranous staining for CXCL12, and nuclear staining for ER. Although expression was observed in several compartments, our evaluation of CXCL12 staining was an overall assessment, not a cellular compartment-specific assessment. Stromal expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4 was absent in all cases and tumor CXCR4 expression was positive in all EC cases. ER expression scores were computed as the sum of the product of staining intensity (0, 1, 2, 3) and proportion of cells staining (range: 0–100%). The total score (H-score) ranged between 0 and 300. Cases with an H-score ≥ 10 were considered positive for ER.28

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables listed in Table 2 were compared across biomarker expression categories using chi-square tests. Clinicopathologic variables of interest were age, race, body mass index (BMI), personal history of cancer, histology subtype, stage, lymph node involvement, metastasis, and tumor size.

Table 2.

Association between CXCL12 expression, ER expression, and clinicopathologic characteristics

| Characteristic N=199 |

Sample counts | Negative CXCL12 (%)† N=36 |

Positive CXCL12 (%)† N=163 |

p* | Negative ER (%)† N=75 |

Positive ER (%)† N=124 |

p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.22 | 0.19 | |||||

| < 65 years | 109 | 27 | 73 | 14 | 86 | ||

| ≥ 65 years | 90 | 44 | 56 | 28 | 72 | ||

| Race | 0.50 | 0.73 | |||||

| White | 179 | 33 | 67 | 19 | 81 | ||

| Non-White | 20 | 21 | 79 | 15 | 85 | ||

| Body Mass Index | 0.21 | 0.22 | |||||

| Normal | 49 | 16 | 84 | 22 | 78 | ||

| Overweight | 58 | 29 | 71 | 33 | 67 | ||

| Obese | 92 | 41 | 59 | 11 | 89 | ||

| Histology subtype | 0.81 | <0.001 | |||||

| Low grade Type I | 76 | 32 | 68 | 8 | 92 | ||

| High grade Type I | 34 | 36 | 64 | 55 | 45 | ||

| Clear cell | 29 | 40 | 60 | 69 | 31 | ||

| Papillary serous | 60 | 29 | 71 | 52 | 48 | ||

| FIGO stage | 0.81 | <0.001 | |||||

| Early stage (I & II) | 103 | 33 | 67 | 15 | 85 | ||

| Late stage (III & IV) | 96 | 31 | 69 | 41 | 59 | ||

| Lymph node involvement | 0.42 | 0.02 | |||||

| Negative | 102 | 25 | 75 | 19 | 81 | ||

| Positive | 37 | 30 | 70 | 48 | 52 | ||

| No nodal exam | 49 | 45 | 55 | 13 | 87 | ||

| Unknown | 11 | 17 | 83 | 17 | 83 | ||

| Metastasis | 0.07 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 158 | 31 | 69 | 17 | 83 | ||

| Yes | 33 | 54 | 46 | 55 | 45 | ||

| Unknown | 8 | 66 | 34 | 66 | 34 | ||

| Tumor size | 0.35 | 0.83 | |||||

| ≤ 2 cm | 26 | 45 | 55 | 15 | 85 | ||

| > 2 cm | 95 | 38 | 62 | 23 | 77 | ||

| Unknown | 78 | 23 | 77 | 18 | 82 | ||

| ER expression | 0.11 | ----- | |||||

| Negative | 75 | 18 | 82 | ----- | ----- | ||

| Positive | 124 | 36 | 64 | ----- | ----- |

Weighted, row percentages

Adjusted Wald test p-value

OS and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were defined as the number of days between the date of diagnosis and the date of death from all causes or date of recurrence, respectively. Patients who did not experience either outcome were censored at the last date of contact or the date of last follow-up (December 31, 2008). For RFS analyses, only cases that were known to be disease-free following the primary surgery were included. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS and RFS and log-rank tests were used to compare survival distributions by CXCL12 expression status in ER negative and ER positive patients. All analyses included sampling weights to estimate proportions and other effect sizes that are representative of the target study population. In Stata 11, the svy family of commands was used to incorporate the sampling weights (StataCorp LP, College Station TX).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows unweighted demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample and the corresponding weighted proportions in the sampling frame. In the sampling frame, 66% of cases were less than 65 years of age at diagnosis, 94% were white, and 53% were obese. Most (77%) had low grade Type I tumors; 13%, 3%, and 7% had high grade Type I, CC, and PS tumors, respectively. Most (86%) were early FIGO stage, and 56% had known negative lymph node involvement. Metastasis was relatively uncommon, with only 4% of cases having a documented metastasis. Tumor size was unknown in 46% of cases, ≤2 cm in 22% of cases, and >2 cm in 31%. A majority (59%) of patients in the sampling frame was treated with surgery only (data not tabled). Thirty-percent of patients had radiotherapy following surgery, and 11% had either chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiotherapy following surgery.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of the EC patients

| Characteristics | n§ (%)† | %‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| < 65 years | 109 (55) | 66 |

| ≥ 65 years | 90 (45) | 34 |

| Race | ||

| White | 179 (90) | 94 |

| Non-White | 20 (10) | 6 |

| Body Mass Index | ||

| Normal (BMI < 25 kg/m2) | 49 (25) | 23 |

| Overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2) | 58 (29) | 23 |

| Obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 92 (46) | 54 |

| Personal history of cancer | ||

| No | 160 (80) | 81 |

| Yes | 35 (17) | 16 |

| Unknown | 4 (2) | 3 |

| Histology subtype | ||

| Low grade Type I | 76 (38) | 77 |

| High grade Type I | 34 (17) | 13 |

| Clear cell | 29 (15) | 3 |

| Papillary serous | 60 (30) | 7 |

| FIGO stage | ||

| Early (I & II) | 103 (52) | 86 |

| Late (III & IV) | 96 (48) | 14 |

| Lymph node involvement | ||

| Negative | 102 (51) | 56 |

| Positive | 37 (18) | 6 |

| No nodes examined | 49 (25) | 36 |

| Unknown | 11 (6) | 2 |

| Metastasis | ||

| No | 158 (79) | 95 |

| Yes | 33 (17) | 4 |

| Unknown | 8 (4) | 1 |

| Tumor size | ||

| ≤ 2 cm | 26 (13) | 22 |

| > 2 cm | 95 (48) | 31 |

| Unknown | 78 (39) | 46 |

sample count

proportion in the study sample, N=199

proportion in the sampling frame, N=1,486

Figure 1 shows representative IHC stains for CXCL12 expression. CXCL12 expression was negative in 63 cases (32%) and positive in 136 cases (68%). CXCL12 expression was somewhat more frequent in cases with no metastases (69%) than in cases with metastases (46%; p=0.07, Table 2). ER expression was negative in 75 cases (38%) and positive in 124 cases (62%). Histology subtype was significantly associated with ER expression (p<0.001); positive ER expression was highest among low grade Type I cases (92%), followed by PS (48%), high grade Type I (45%) and CC cases (31%). Stage (p<0.001), lymph node involvement (p=0.02), and metastases (p<0.001) were significantly associated with ER expression. Early stage cases had a significantly higher prevalence of positive ER expression compared to late stage cases (85% vs. 59%). Among cases with negative lymph involvement, 81% had positive ER expression compared to 52% among cases with positive lymph node involvement. Positive ER expression was observed in 45% of metastatic cases compared to 83% among non-metastatic cases. CXCL12 expression and ER expression were not significantly associated with each other (p=0.11).

Figure 1.

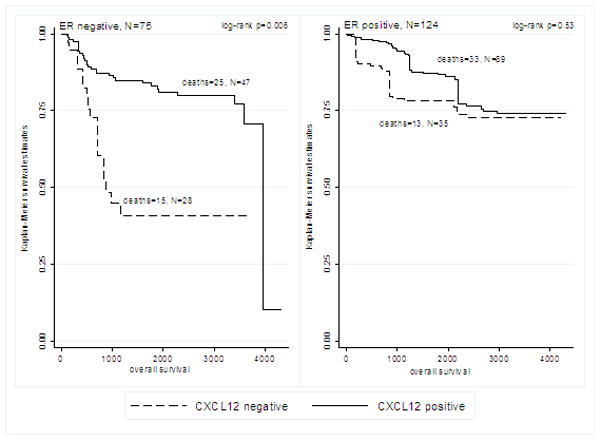

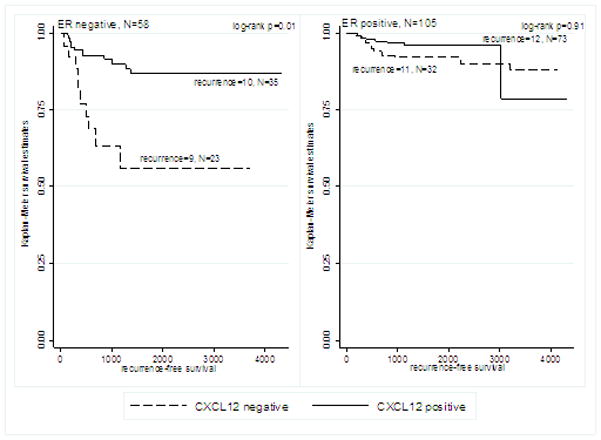

Median follow-up time in the sample was 1,260 days (range: 24 days – 4,328 days). The association between CXCL12 expression and survival outcomes differed by ER expression status. In ER negative patients, positive CXCL12 expression was significantly associated with longer OS (log-rank p=0.006, Figure 2A) and longer RFS (log-rank p=0.01, Figure 3A). CXCL12 expression was not significantly associated with OS or RFS in ER positive patients (Figures 2B and 3B).

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

We examined the role of CXCR4, CXCL12, and ER expression in a diverse sample of EC cases. CXCR4 was expressed by all cases in this study. Although no significant association between CXCL12 expression and ER expression was observed, positive CXCL12 expression was significantly associated with better OS and RFS in ER negative cases. No association between CXCL12 and survival outcomes in ER positive patients was observed. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the prognostic significance of concurrent CXCL12 and ER expression in EC patients.

Chemokines are an important class of stromal-derived signaling proteins which contribute to tissue maintenance and repair by binding specific receptors expressed by target cells. For a particular chemokine ligand-receptor pair, high concentrations of the ligand “chemoattract” cells that express the receptor through a chemokine gradient. CXCR4 is typically expressed by immune cells, such as hematopoietic cells, T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes, monocytes and macrophages, as well as cells of the liver, kidney, brain, lung, and colon.29 Upon binding, downstream processes such as chemotaxis, cell survival and proliferation, increases in intracellular calcium, and gene transcription are triggered.29 Among the chemokine ligand-receptor pairs examined in the cancer literature, the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is the most frequently studied. During carcinogenesis, tumor cells may acquire CXCR4 expression as a result of hypoxic tissue conditions or activating mutations. Consequently, CXCR4-expressing cancer cells have the potential to metastasize to tissues that abundantly express CXCL12 via a chemokine gradient. By analogy, positive expression of CXCL12 at the primary tumor site presumably would suppress the metastasis of CXCR4-expressing cells, which has been shown in colon30 and breast cancer models.31

Previous EC studies have investigated the association between CXCR4 and/or CXCL12 expression and tumor grade,21, 32 myometrial invasion,33 and survival.26 Using IHC, Mizokami et al. reported CXCR4 and CXCL12 protein expression were significantly higher in low grade Type I tumors (N=27) compared to high grade Type I tumors (N=15).32 Conversely, Gelmini et al. reported that IHC expression of CXCR4 showed high and uniform staining among 41 Type I tumors with different grades of differentiation.21 Our result that CXCR4 was moderately or strongly expressed by all ECs agrees with findings from Gelmini et al.

Interestingly, stromal expression of CXCL12 was not apparent in our study. Based on the biology of CXCL12 in normal tissues,20 we anticipated that CXCL12 would be expressed by infiltrating stromal cells. However, other studies have reported CXCL12 and CXCR4 production in primary tumors, which supports the hypothesis that autocrine signaling enhances tumor proliferation.30–31 With respect to ER, we observed less aggressive tumor characteristics among patients with positive ER expression, i.e. low grade, early stage, negative lymph node involvement, and no metastases, which confirms previously published reports.8, 34

Our prognostic results are in accordance with large studies performed in breast cancer patients. Mirisola, Hassan, and Kobayashi reported that CXCL12 expression was an independent and significant prognostic factor for better OS and RFS.17–19 Two of these studies reported an association between CXCL12 and better prognosis regardless of ER expression,17, 19 while one study reported the association only in ER positive cases.18 These studies proposed that the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis mediates survival through directional movement of cancer cells during metastasis. Tumor cells lacking CXCL12 but maintaining CXCR4 expression may selectively migrate to tissues with high levels of CXCL12; however, tumors expressing high levels of both CXCR4 and CXCL12 may be less likely to metastasize, resulting in a favorable prognosis.30–31 Indeed, we observed a borderline significant negative association between CXCL12 expression and metastasis, i.e., expression of CXCL12 by the primary tumor was associated with reduced probability of metastases. ER may contribute to this paradigm as it forms an important positive feedback loop with CXCL12 and CXCR4.23 Studies of other cancer sites, including pancreatic cancer35 and colorectal cancer,36 report that CXCL12 expression is a strong prognostic factor for poor survival outcomes. These studies emphasize the conflicting role that CXCL12 plays in various cancers, appearing protective in some cancers and associated with poor outcomes in others.

A major strength of this clinicopathologic study is the inclusion of a large sample of high grade Type I, CC, and PS tumors compared to other published case series; this group of aggressive ECs is characterized by advanced stage, poor differentiation, and metastasis. Furthermore, the large sample size allowed us to investigate the prognostic significance of CXCL12 by ER status. Other strengths include the high quality pathology data, information on potential confounders, and use of archived tissue specimens.

One limitation of this study is the unavailability of tumor blocks for some cases who differed from included cases with respect to stage and histology type; this may have introduced selection bias. Another potential limitation is our use of IHC to detect protein expression. Although IHC is subjective and semi-quantitative, IHC is widely used in clinical pathology and research. Finally, although we included a large number of cases, the small numbers of cases and events within histology subtypes precluded subgroup analyses. As we observed a significant association between CXCL12 and survival in ER negative cases, this marker may be particularly useful for EC subtypes that typically have low ER expression, i.e. high grade Type I and Type II.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that CXCL12 expression is associated with longer OS and RFS among ER negative EC patients. In addition to stage and histology subtype, these biomarkers may be relevant for identifying a subset of patients who will have a better outcome, and potentially could avoid adjuvant therapy. Future EC studies of this pathway should examine a larger sample of patients to confirm these findings. Furthermore, basic science studies that examine mechanisms associated with CXCL12 expression in EC would increase knowledge regarding this pathway.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant R25-CA057703.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Mendivil A, Schuler KM, Gehrig PA. Non-endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: a review of selected histological subtypes. Cancer Control. 2009;16(1):46–52. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasool N, Fader AN, Seamon L, Neubauer NL, Shahin FA, Alexander HA, Moore K, Moxley K, Secord AA, Kunos C, Rose PG, O’Malley DM. Stage I, grade 3 endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: an analysis of clinical outcomes and patterns of recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116(1):10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidaka T, Kato K, Yonezawa R, Shima T, Nakashima A, Nagira K, Nakamura T, Saito S. Omission of lymphadenectomy is possible for low-risk corpus cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(1):86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soslow RA, Bissonnette JP, Wilton A, Ferguson SE, Alektiar KM, Duska LR, Oliva E. Clinicopathologic analysis of 187 high-grade endometrial carcinomas of different histologic subtypes: similar outcomes belie distinctive biologic differences. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(7):979–87. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31802ee494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petignat P, Usel M, Gauthier P, Popowski Y, Pelte MF, Bouchardy C, Verkooijen HM. Outcome of uterine clear cell carcinomas compared to endometrioid carcinomas and poorly-differentiated endometrioid carcinomas. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton CA, Cheung MK, Osann K, Chen L, Teng NN, Longacre TA, Powell MA, Hendrickson MR, Kapp DS, Chan JK. Uterine papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas predict for poorer survival compared to grade 3 endometrioid corpus cancers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(5):642–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alektiar KM, McKee A, Lin O, Venkatraman E, Zelefsky MJ, McKee B, Hoskins WJ, Barakat RR. Is there a difference in outcome between stage I–II endometrial cancer of papillary serous/clear cell and endometrioid FIGO Grade 3 cancer? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02913-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu W, Slomovitz BM, Celestino J, Chung L, Thornton A, Lu KH. Coordinate expression of Cdc25B and ER-alpha is frequent in low-grade endometrioid endometrial carcinoma but uncommon in high-grade endometrioid and nonendometrioid carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63(19):6195–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelsen IB, Stefansson IM, Akslen LA, Salvesen HB. GATA3 expression in estrogen receptor alpha-negative endometrial carcinomas identifies aggressive tumors with high proliferation and poor patient survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):543, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(7):540–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-Baruch A. Organ selectivity in metastasis: regulation by chemokines and their receptors. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25(4):345–56. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlotnik A. Chemokines in neoplastic progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14(3):181–5. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, Barrera JL, Mohar A, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410(6824):50–6. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kollmar O, Rupertus K, Scheuer C, Junker B, Tilton B, Schilling MK, Menger MD. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 promotes cell migration and tumor growth of colorectal metastasis. Neoplasia. 2007;9(10):862–70. doi: 10.1593/neo.07559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Terauchi M, Ino K, Nawa A, Kikkawa F. Involvement of SDF-1alpha/CXCR4 axis in the enhanced peritoneal metastasis of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(1):91–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koshiba T, Hosotani R, Miyamoto Y, Ida J, Tsuji S, Nakajima S, Kawaguchi M, Kobayashi H, Doi R, Hori T, Fujii N, Imamura M. Expression of stromal cell-derived factor 1 and CXCR4 ligand receptor system in pancreatic cancer: a possible role for tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(9):3530–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mirisola V, Zuccarino A, Bachmeier BE, Sormani MP, Falter J, Nerlich A, Pfeffer U. CXCL12/SDF1 expression by breast cancers is an independent prognostic marker of disease-free and overall survival. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(14):2579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi T, Tsuda H, Moriya T, Yamasaki T, Kikuchi R, Ueda S, Omata J, Yamamoto J, Matsubara O. Expression pattern of stromal cell-derived factor-1 chemokine in invasive breast cancer is correlated with estrogen receptor status and patient prognosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123(3):733–45. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0672-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassan S, Ferrario C, Saragovi U, Quenneville L, Gaboury L, Baccarelli A, Salvucci O, Basik M. The influence of tumor-host interactions in the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 ligand/receptor axis in determining metastatic risk in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(1):66–73. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz A, Salvo VA, Ruiz LA, Baez P, Garcia M, Flores I. Basal and steroid hormone-regulated expression of CXCR4 in human endometrium and endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2010;17(10):894–903. doi: 10.1177/1933719110379920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelmini S, Mangoni M, Castiglione F, Beltrami C, Pieralli A, Andersson KL, Fambrini M, Taddei GL, Serio M, Orlando C. The CXCR4/CXCL12 axis in endometrial cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26(3):261–8. doi: 10.1007/s10585-009-9240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mylonas I, Jeschke U, Shabani N, Kuhn C, Kriegel S, Kupka MS, Friese K. Normal and malignant human endometrium express immunohistochemically estrogen receptor alpha (ER-alpha), estrogen receptor beta (ER-beta) and progesterone receptor (PR) Anticancer Res. 2005;25(3A):1679–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sauve K, Lepage J, Sanchez M, Heveker N, Tremblay A. Positive feedback activation of estrogen receptors by the CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5793–800. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao D, Li XP, Gao M, Zhao C, Wang JL, Wei LH. Stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha stimulates human endometrial carcinoma cell growth through the activation of both extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and Akt. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103(3):932–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubarek L, Jagodzinski PP. Epigenetic up-regulation of CXCR4 and CXCL12 expression by 17 beta-estradiol and tamoxifen is associated with formation of DNA methyltransferase 3B4 splice variant in Ishikawa endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(7):1441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodama J, Hasengaowa, Seki N, Kusumoto T, Hiramatsu Y. Expression of the CXCR4 and CCR7 chemokine receptors in human endometrial cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2007;28(5):370–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felix AS, Weissfeld JL, Stone RA, Bowser R, Chivukula M, Edwards RP, Linkov F. Factors associated with Type I and Type II endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(11):1851–6. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodi Z, Chakrabarti J, Lee AH, Ronan JE, Elston CW, Cheung KL, Robertson JF, Ellis IO. The reliability of assessment of oestrogen receptor expression on needle core biopsy specimens of invasive carcinomas of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(3):299–302. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.036665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teicher BA, Fricker SP. CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(11):2927–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wendt MK, Johanesen PA, Kang-Decker N, Binion DG, Shah V, Dwinell MB. Silencing of epithelial CXCL12 expression by DNA hypermethylation promotes colonic carcinoma metastasis. Oncogene. 2006;25(36):4986–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wendt MK, Cooper AN, Dwinell MB. Epigenetic silencing of CXCL12 increases the metastatic potential of mammary carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2008;27(10):1461–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizokami Y, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Ino K, Kikkawa F, Mizutani S. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha-induced cell proliferation and its possible regulation by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;110(5):652–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukamoto H, Shibata K, Kajiyama H, Terauchi M, Nawa A, Kikkawa F. Uterine smooth muscle cells increase invasive ability of endometrial carcinoma cells through tumor-stromal interaction. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24(6):423–9. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujimoto J, Sato E. Clinical implication of estrogen-related receptor (ERR) expression in uterine endometrial cancers. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;116(1–2):71–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang JJ, Zhu S, Bruggeman R, Zaino RJ, Evans DB, Fleming JB, Gomez HF, Zander DS, Wang H. High levels of expression of human stromal cell-derived factor-1 are associated with worse prognosis in patients with stage II pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(10):2598–604. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akishima-Fukasawa Y, Nakanishi Y, Ino Y, Moriya Y, Kanai Y, Hirohashi S. Prognostic significance of CXCL12 expression in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132(2):202–10. doi: 10.1309/AJCPK35VZJEWCUTL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]