Abstract

Objective To determine whether people who donate a kidney have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Design Retrospective population based matched cohort study.

Participants All people who were carefully selected to become a living kidney donor in the province of Ontario, Canada, between 1992 and 2009. The information in donor charts was manually reviewed and linked to provincial healthcare databases. Matched non-donors were selected from the healthiest segment of the general population. A total of 2028 donors and 20 280 matched non-donors were followed for a median of 6.5 years (maximum 17.7 years). Median age was 43 at the time of donation (interquartile range 34-50) and 50 at the time of follow-up (42-58).

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was a composite of time to death or first major cardiovascular event. The secondary outcome was time to first major cardiovascular event censored for death.

Results The risk of the primary outcome of death and major cardiovascular events was lower in donors than in non-donors (2.8 v 4.1 events per 1000 person years; hazard ratio 0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.48 to 0.90). The risk of major cardiovascular events censored for death was no different in donors than in non-donors (1.7 v 2.0 events per 1000 person years; 0.85, 0.57 to 1.27). Results were similar in all sensitivity analyses. Older age and lower income were associated with a higher risk of death and major cardiovascular events in both donors and non-donors when each group was analysed separately.

Conclusions The risk of major cardiovascular events in donors is no higher in the first decade after kidney donation compared with a similarly healthy segment of the general population. While we will continue to follow people in this study, these interim results add to the evidence base supporting the safety of the practice among carefully selected donors.

Introduction

In the general population there is a robust association between reduced kidney function and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.1 It is possible that this risk could apply to the over 27 000 registered people who donate a kidney worldwide each year.2 Donors lose half their renal mass, and, similar to reduced kidney function for other reasons, donor nephrectomy can increase blood pressure and metabolites such as uric acid.3 4 These physiological markers, however, might not be valid surrogates in donors for the clinically relevant outcomes that patients and their providers are most interested in. Cardiovascular disease is a key event of interest and is a leading cause of death. Five studies have considered the risk of all cause mortality after kidney donation (studies from the United States, Sweden, Norway, and Japan.5 6 7 8 9) Reassuringly, all five showed no evidence of increased long term mortality among kidney donors. One of these studies also found no higher risk of cardiovascular mortality.8 In a preliminary study we also found no evidence of a higher risk of major cardiovascular events in 1278 people who donated a kidney.10 Limitations of the analysis with respect to study size and characteristics of the matched non-donors, however, meant that uncertainties persisted with these findings.11 12 13

We conducted a study that dealt with many of the previous limitations. We manually reviewed the medical charts of over 2000 living kidney donors in the largest province in Canada, linked this information to universal healthcare databases to reliably identify major cardiovascular events long term with little loss to follow-up, and used methods of restriction and matching to select the healthiest segment of the general population with which donor outcomes could be compared. We also performed subgroup analyses according to the year of nephrectomy (duration of follow-up) to identify any trends in risk with a longer period of follow-up. We did this study because better knowledge of major cardiovascular events in people who become living kidney donors maintains public trust in the transplantation system, informs the choices of potential donors and recipients, and guides follow-up care to maintain good long term health.

Methods

Design and setting

We conducted a population based matched cohort study in Ontario, Canada. Ontario currently has about 13 million residents.14 Residents have universal access to hospital care and physician services. The reporting of this study follows guidelines set out for observational studies.15

Data sources

We ascertained personal characteristics, covariate information, and outcome data from records in four databases. Trillium Gift of Life is Ontario’s central organ and tissue donation agency. This database is unique in that it captured information on living kidney donors in the province at the time of donation. We manually reviewed the medical charts of all people who underwent donor nephrectomy at all five major transplant centres in Ontario between 1992 and 2009 to ensure the accuracy of donor information in the Trillium database. The Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (CIHI-DAD) records detailed diagnostic and procedural information for all admissions to hospital in Ontario. The Ontario Health Insurance Plan database (OHIP) contains all health claims for inpatient and outpatient physician services. The Ontario Registered Persons Database (RPDB) contains demographic and vital status information on all Ontario residents. These databases have been used extensively to research health outcomes and health services.16 17 18 19 20 The databases were essentially complete for all variables used in this study.

Population

We included all living kidney donors who were permanent residents of Ontario. The date of the nephrectomy served as the start date for donor follow-up and was designated the index date. Choosing the best type of non-donors with which donors can be compared is central to any study of relative risks associated with donor nephrectomy.21 Donors go through a detailed selection process and are inherently healthier than the general population. We used techniques of restriction and matching to select the healthiest segment of the general population. We randomly assigned an index date to the entire adult general population according to the distribution of index dates in donors. We then identified comorbidities and measures of access to healthcare from the beginning of available database records (1 July 1991) to the index date. This provided an average of 11 years of medical records for baseline assessment, with 99% of people having at least two years of baseline data for review. Among the general population we excluded any adult with any medical condition before the index date that could preclude donation. This included evidence of diagnostic, procedural, or visit codes for any of genitourinary disease, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, liver disease, rheumatological conditions, chronic infections, a history of nephrology consultation, and evidence of frequent physician visits (more than four visits in the previous two years). We also excluded any person who failed to see a physician at least once in the two years before the index date (given that Ontario has a shortage of physicians we wanted to ensure that non-donors had evidence of access for routine healthcare needs including preventative health measures; we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we removed this exclusion and the study results were not materially different). From a total of 9 643 344 adult Ontarians during the period of interest, our selection procedures resulted in the exclusion of 85% of adults (n=8 216 038). From the adults remaining we then matched 10 non-donors to each donor. We matched on age (within two years), sex, index date (within six months), rural (population less than 10 000) or urban residence, and income (categorised into fifths of average neighbourhood income on the index date).

Outcomes

All people were followed until 31 March 2010 or emigration from the province. The primary outcome was a composite of time to death or first major cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary angioplasty, coronary bypass surgery, carotid endarterectomy, repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm, or peripheral vascular bypass surgery). The secondary outcomes were time to first major cardiovascular event censored for death and components of the primary outcome analysed separately. These outcomes were defined by using codes proved to have good validity when compared with chart review (see appendix on bmj.com). We examined the characteristics associated with death and first major cardiovascular event separately in donors and non-donors. These characteristics were age (per five years), sex, rural or urban residence, income fifth, and year of index date (per year).

Statistical analysis

We assessed differences in baseline characteristics between donors and non-donors using standardised differences.22 23 This metric describes differences between group means relative to the pooled standard deviation; differences greater than 10% reflect the potential for meaningful imbalance. We used a two sided log rank test stratified on matched sets to compare differences in death and cardiovascular outcomes between donors and non-donors. We used Cox regression stratified on matched sets to calculate the hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The proportional hazards assumption was met (non-significant donor×follow-up time interaction term, P=0.27). We repeated the primary analysis in four prespecified subgroups defined by the median age at the index date (≤55 v >55), sex, first degree relative with kidney failure, and index date (1992-2001 (median follow-up 11.4 years, interquartile range 9.5-13.8) v 2002-9 (4.0 years, 2.4-4.8)). We defined subgroups by the characteristic in donors, with non-donors following their matched donor. We examined whether hazard ratios differed among subgroups using a series of pairwise standard z tests.24 We examined the characteristics associated with a first major cardiovascular event separately in donors and non-donors using Cox regression. We conducted all analysis with SAS software version 9.2.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics for 2028 living kidney donors and 20 280 matched non-donors. The median age was 43 (interquartile range 34-50), and 60% were women. As expected, donors had more physician visits in the year before the index date than non-donors because such visits are a necessary part of the evaluation process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of kidney donors and non-donors at time of transplantation*. Figures are numbers (percentage) unless stated otherwise

| Donors (n=2028) | Non-donors (n=20 280) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) age (years) | 43 (34-50) | 43 (34-50) |

| Women | 1216 (60) | 12 160 (60) |

| Income fifth: | ||

| Lowest | 301 (15) | 3010 (15) |

| Middle | 430 (21) | 4300 (21) |

| Highest | 470 (23) | 4700 (23) |

| Rural town | 278 (14) | 2780 (14) |

| Median (IQR) No of visits to physician in previous year† | 11 (8-15) | 1 (0-2) |

| Year: | ||

| 1992-5 | 217 (11) | 2170 (11) |

| 1996-2000 | 531 (26) | 5315 (26) |

| 2001-5 | 683 (34) | 6833 (34) |

| 2006-9 | 597 (29) | 5962 (29) |

IQR=interquartile range.

*Also referred to as index date, randomly assigned to non-donors to establish start of time follow-up.

†Indicates standardised difference between donors and non-donors >10%. Standardised differences are less sensitive to sample size than traditional hypothesis tests. They provide measure of difference between groups divided by pooled SD; value >10% is interpreted as meaningful difference between groups. As expected, donors had more physician visits in year before index date than non-donors, as such visits are necessary for donor evaluation process.

Most living kidney donors were siblings of the recipients (35%), followed by spouses (19%), parents (14%), and children (13%). Nearly half (43%) of the nephrectomies were performed laparoscopically, and the rest were done with an open procedure. Before donation, the median serum creatinine was 77 µmol/L (interquartile range 66-86 µmol/L) (equivalent to 0.87 mg/dL, 0.75-0.97 mg/dL) and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 97 mL/min/1.73 m2 (86-109) (with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula (CKD-EPI).25 The median length of follow-up was 6.5 years (6.8 years in donors, 6.4 years in non-donors, maximum 17.7 years). A total of 609 donors and 5744 non-donors were followed for a period of 10 years or more. The median age at the time of last follow-up for the entire cohort was 50 (42-58). Of the 22 308 individuals (2028 donors, 20 280 non-donors), 20 450 (91.7%) were alive at the end of study follow-up (31 March 2010) and had not experienced a major cardiovascular event, and 1206 (5.4%) were censored at a time of emigration from the province (48 (2.4%) donors, 1158 (5.7%) non-donors). The total person years of follow-up was 162 508 (15 176 donors, 147 332 non-donors).

Outcomes

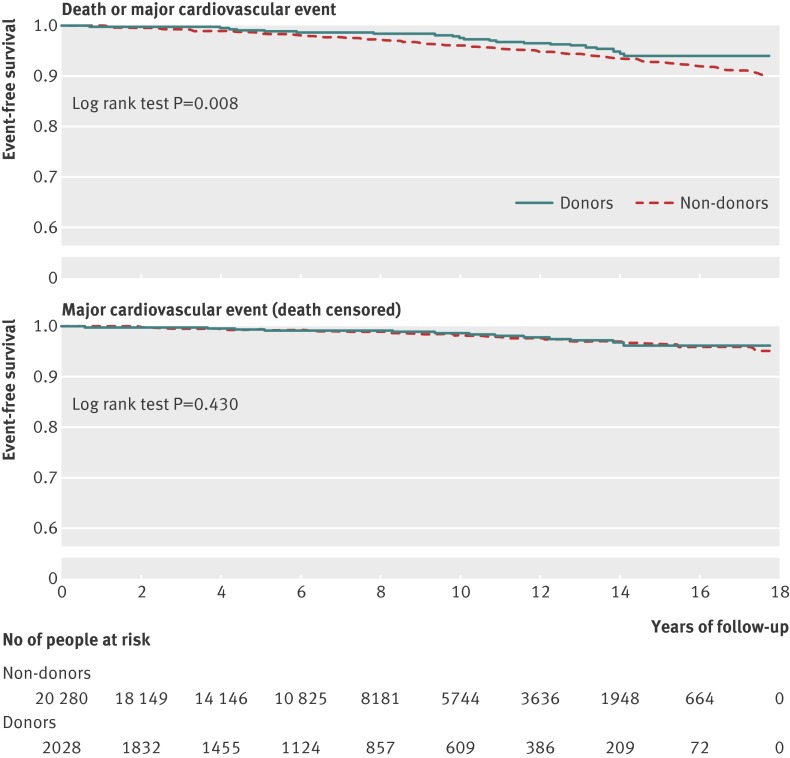

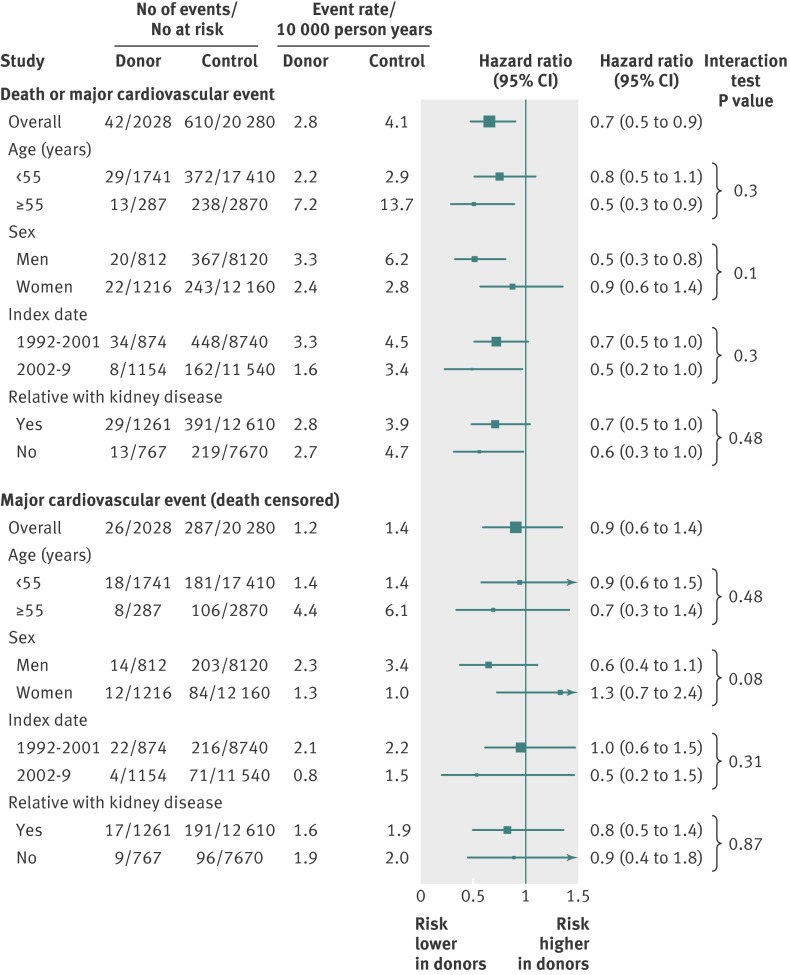

Figure 1 and table 2 present the main outcomes . There were 381 deaths (16 donors, 365 non-donors) and 313 major cardiovascular events (26 donors, 287 non-donors). The risk of death or first major cardiovascular event was lower in donors than in non-donors (2.1% v 3.0%; 2.8 v 4.1 events per 1000 person years; hazard ratio 0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.48 to 0.90; log rank P=0.01). Table 2 shows the types of cardiovascular events. There was no significant difference in the risk of major cardiovascular events censored for death between donors and non-donors (1.3% v 1.4%, 1.7 v 2.0 events per 1000 person years; hazard ratio 0.85, 0.57 to 1.27). Figure 2 shows the subgroup analyses. An earlier index date (longer period of follow-up) did not influence the association between kidney donation and the primary outcome, nor did older age at index date, sex, or history of a first degree biological relative with kidney failure (P value for interaction ranged from 0.10 to 0.48). Subgroup results were similar for the outcome of time to first major cardiovascular event censored for death. Older age and lower income were associated with a higher risk of death or first major cardiovascular event in both donors and non-donors when each group was examined separately (table 3).

Fig 1 Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival probability without death or major cardiovascular event (top) and without major cardiovascular event (censored for death, bottom)

Table 2.

Death or major cardiovascular events among kidney donors and non-donors

| Donors (n=2028) | Non-donors (n=20 280) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) follow-up (years) | 6.8 (3.7 to 10.9) | 6.4 (3.5 to 10.6) |

| Range follow-up (years) | 0.5-17.7 | 0.1-17.7 |

| Total follow-up (person years) | 15 176 | 147 332 |

| No (%) of events | 42 (2.1) | 610 (3.0) |

| No of events per 1000 person years* | 2.8 | 4.1 |

| Model based risk ratios (95% CI) | 0.66 (0.48 to 0.90) | 1.0 (reference) |

| No (%) of types of events†: | ||

| Death | 16 (0.8) | 365 (1.8) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 14 (0.7) | 141 (0.7) |

| Coronary artery angioplasty or surgery | 15 (0.7) | 179 (0.9) |

| Stroke | 5 (0.2) | 51 (0.2) |

IQR=interquartile range.

*P=0.01, stratified log rank test.

†Events of carotid endarterectomy, abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and peripheral vascular bypass surgery were rare (≤25 events for all three outcomes combined for donors and non-donors combined) and are not reported here for reasons of privacy. Events reported here are not mutually exclusive; individual might have had more than one event in follow-up. In survival models we considered time to first event.

Fig 2 Influence of age, sex, index date (duration of follow-up), and relative with kidney failure on risk of death or first major cardiovascular event (top) and first major cardiovascular event (censored for death, bottom). Individuals with index date of 1992-2001 had median follow-up 11.4 years (interquartile range 9.5-13.8); individuals with index date of 2002-9 had median follow-up 4.0 years (2.4 to 5.8)

Table 3.

Risk factors for death or major cardiovascular events in kidney donors and non-donors* when each group was analysed separately. Figures are rate ratios (95% CI)

| Donors | Non-donors | |

|---|---|---|

| Death or major cardiovascular event | ||

| Older age (per 5 years)† | 1.44 (1.25 to 1.66) | 1.61 (1.55 to 1.68) |

| Women (v men) | 0.73 (0.40 to 1.33) | 0.43 (0.37 to 0.51) |

| Rural residence (v urban residence) | 0.58 (0.21 to 1.62) | 1.06 (0.86 to 1.32) |

| Higher income fifth (per fifth) | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.96) | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.90) |

| More recent year of index (per year) | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.08) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.01) |

| Major cardiovascular event (death censored) | ||

| Older age (per 5 years)† | 1.47 (1.23 to 1.75) | 1.60 (1.51 to 1.69) |

| Women (v men) | 0.57 (0.26 to 1.23) | 0.27 (0.21 to 0.35) |

| Rural (v urban) residence | 0.70 (0.21 to 2.34) | 1.23 (0.91 to 1.65) |

| Higher income fifth (per fifth) | 0.83 (0.63 to 1.10) | 0.86 (0.79 to 0.93) |

| More recent year of index (per year) | 0.92 (0.81 to 1.04) | 0.98 (0.94 to 1.01) |

*Separate multivariable Cox regression models created for kidney donors and non-donors.

†Refers to individual’s age at beginning of follow-up (also referred to as index date or cohort entry date).

Discussion

The risk of major cardiovascular events in people who donate a kidney is no higher in the first decade after transplantation than in matched non-donors. There is no trend of increased cardiovascular risk in subgroups of donors with a longer (compared with shorter) period of follow-up, nor do Kaplan Meier curves after 10 years of follow-up suggest any higher risk of death or major cardiovascular events in donors compared with non-donors.

We conducted this study to determine whether people who donate a kidney have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease than a similarly healthy segment of the general population. While we will continue to follow up people in this study, these interim results provide important safety reassurances to donors, their recipients, and transplant professionals. Reassuringly, with longer follow-up the observed risk for the primary outcome continued to be lower in donors than in non-donors. As stated by others, we attribute this lower risk to the rigorous selection process of establishing excellent health before donation, which includes psychological assessment and counselling, abdominal imaging, cancer screening, and an assessment for chronic infectious diseases.7 Healthy lifestyle behaviours are also emphasised at this time. Restriction of non-donors to the healthiest segment of the general population, as done in this study, still did not replicate this process.

Strengths and limitations of study

Our analyses meaningfully assessed major cardiovascular events in previous kidney donors.10 We were able to do this because of the universal healthcare benefits in the province of Ontario, with the collection of all healthcare encounters for all citizens. This reduces concerns about selection and information biases. As mentioned, for the present study we manually reviewed over 2000 consecutive medical charts to ensure the accuracy of donor information presented in this study. The large number of donors and non-donors provided good precision for the estimates we provide. Outcomes of death and major cardiovascular events were ascertained in a reliable and valid manner in our data sources. Loss to follow-up, a concern in many long term follow-up studies of donors, was minimal in our setting (less than 6% of people emigrated from the province during follow-up). Our data, however, are not without limitations. Cause of death could not be reliably assessed in our data sources. Our results describing major cardiovascular events, however, are consistent with a study from Norway that showed no higher risk of cardiovascular mortality in people who donated a kidney compared with the general population (median follow-up 14.3 years from nephrectomy).8 Accurate racial information was not available. Given that 75% of Ontario residents are white, these results might generalise less well to non-white donors.26 The acceptance criteria of living donors in our region during the period of review were quite stringent.27 Thus, these data should not be generalised to the recent practice of accepting donors with health conditions such as obesity or hypertension.28 Information on kidney function and family history of kidney disease were unavailable in non-donors, and measurements such as blood pressure and body mass index (BMI) before transplantation were unavailable in both donors and non-donors. This information might have allowed for better selection of non-donors. Collection of such information in the number of individuals needed to adequately examine cardiovascular events in our setting, however, would have been prohibitively expensive, with results unavailable for another decade. Finally, we did not have data on glomerular filtration rate in donors during follow-up, which precluded an assessment of cardiovascular risk according to this feature.

Comparison with other studies

A collaborative meta-analysis of multiple general population non-donor cohorts has recently summarised the association between reduced kidney function and cardiovascular disease.1 Over a median follow-up of eight years, the risk of cardiovascular mortality increases with a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate. Compared with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 90-104 mL/min/1.73 m², hazard ratios for cardiovascular mortality are 1.03 (95% confidence interval 0.85 to 1.24) for an estimated rate of 75-89 mL/min/1.73 m², 1.09 (0.92 to 1.29) for an estimated rate of 60-74 mL/min/1.73 m², 1.52 (1.18 to 1.97) for an estimated rate of 45-59 mL/min/1.73 m², and 2.04 (1.80 to 3.21) for an estimated rate of 30-44 mL/min/1.73 m². Similar associations with narrower confidence intervals are seen for all cause mortality. Concurrent evidence of albuminuria increases these risks. In the donor setting, about 10% of individuals show 300 mg or more of proteinuria a day in the decade after donation. Donors are more likely to develop microalbuminuria than the general population. In addition, in the decade after donation 40% of people who donate a kidney have a glomerular filtration rate of 60-80 mL/min/1.73 m² and 10% have a of 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m².29 30

So how does one reconcile the lack of observed risk of cardiovascular disease among living donors in the current study with the observed risk among individuals with reduced glomerular filtration rate in general population cohorts? Firstly, the association seen in the general population might not be causal. It might, for example, reflect systemic atherosclerosis related to diabetes, hypertension, and older age, which coexist with reduced glomerular filtration rate but which are not fully accounted for in multivariable models. On the other hand, donors develop reduced glomerular filtration rate and low grade proteinuria through a non-pathological process, which might not carry the same prognostic relevance. Secondly, the process of donor evaluation is used to select individuals who are in excellent health with good long term prognosis. In our setting, follow-up healthcare is a universal benefit to all Canadians, and we have previously confirmed that donors tend to have more have routine primary healthcare visits in follow-up than non-donors.10 These elements of healthcare, which can include early detection and management of cardiovascular risk factors, could offset any increase in risk of cardiovascular disease attributable to reduced glomerular filtration rate. If unmeasured baseline cardiovascular risk factors were more prevalent in non-donors than donors in our study, however, this could have masked evidence of an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in donors. For these reasons it remains prudent to counsel all donors on modifiable risk factors that prevent future cardiovascular disease both before and after the donation process. In our study the non-modifiable factor of older age and the difficult to modify factor of low income were similarly associated with death and cardiovascular events in donors and non-donors. Finally, it is possible that an association between living donation and risk of cardiovascular disease does exist but takes much longer to manifest. It might depend on more donors entering an older age range and manifesting a glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the decades after donation. For this reason, ongoing follow-up of this and other donor cohorts is warranted.

Conclusion

Taken together with other studies that have shown no increase in mortality in the decades after kidney donation, the present study adds to the available evidence base supporting the safety of the practice among carefully selected donors.27 The results do not provide evidence to justify relaxing the rigorous criteria used to select people who become kidney donors.

What is already known on this topic

Each year over 27 000 people around the world become a kidney donor, and the number is increasing in response to a shortage of kidneys for transplantation from deceased donors

In the general population there is a robust association between reduced kidney function and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease

Similar to reduced kidney function for other reasons, donor nephrectomy could increase blood pressure, which is a potent risk factor for cardiovascular disease

What this study adds

The risk of major cardiovascular events was no higher in the first decade after people had donated a kidney than in a similarly healthy segment of the general population

The results add to the evidence base supporting the safety of the practice among carefully selected donors

We thank Ping Li and Nelson Chong from the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, and Frank Markel, Versha Prakash, and Keith Wong from Trillium Gift of Life Network for their support. We also thank Laura Agar, Nishant Fozdar, Mary Salib, and Robyn Winterbottom, who abstracted data from medical charts at five transplant centres for this project.

Donor Nephrectomy Outcome Research (DONOR) Network Investigators

Jennifer Arnold, Neil Boudville, Ann Bugeya, Christine Dipchand, Mona Doshi, Liane Feldman, Amit Garg, Colin Geddes, Eric Gibney, John Gill, Martin Karpinski, Joseph Kim, Scott Klarenbach, Greg Knoll, Ngan Lam, Charmaine Lok, Philip McFarlane, Mauricio Monroy-Cuadros, Norman Muirhead, Immaculate Nevis, Christopher Y Nguan, Chirag Parikh, Emilio Poggio, G V Ramesh Prasad, Jessica Sontrop, Leroy Storsley, Ken Taub, Sonia Thomas, Darin Treleaven, Ann Young.

Contributors: All authors contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and revising the paper. AXG is guarantor.

Funding: This project was conducted at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). ICES is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). AXG was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Clinician-Scientist Award. GK was supported by a University of Ottawa Chair in Clinical Transplantation Research. SK was supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research/Alberta Innovates Health Solutions, a joint initiative between Alberta Health and Wellness and the University of Alberta. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent of the funding sources. The funding sources did not influence any aspect of this study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was conducted according to a prespecified protocol, which was approved by the research ethics board at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (Toronto, ON, Canada).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;344:e1203

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Definition of death and cardiovascular events using valid diagnostic and procedural codes in Ontario healthcare databases

References

- 1.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:2073-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horvat LD, Shariff SZ, Garg AX. Global trends in the rates of living kidney donation. Kidney Int 2009;75:1088-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudville N, Prasad GV, Knoll G, Muirhead N, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Yang RC, et al. Meta-analysis: risk for hypertension in living kidney donors. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:185-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young A, Nevis IF, Geddes C, Gill J, Boudville N, Storsley L, et al. Do biochemical measures change in living kidney donors? A systematic review. Nephron Clin Pract 2007;107:c82-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, Rogers T, Bailey RF, Guo H, et al. Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med 2009;360:459-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, Mehta SH, Singer AL, Taranto SE, et al. Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA 2010;303:959-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Elinder CG, Stenbeck M, Tyden G, Groth CG. Kidney donors live longer. Transplantation 1997;64:976-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mjoen G, Reisaeter A, Hallan S, Line PD, Hartmann A, Midtvedt K, et al. Overall and cardiovascular mortality in Norwegian kidney donors compared to the background population. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamoto M, Akioka K, Nobori S, Ushigome H, Kozaki K, Kaihara S, et al. Short- and long-term donor outcomes after kidney donation: analysis of 601 cases over a 35-year period at Japanese single center. Transplantation 2009;87:419-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg AX, Prasad GV, Thiessen-Philbrook HR, Ping L, Melo M, Gibney EM, et al. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension risk in living kidney donors: an analysis of health administrative data in Ontario, Canada. Transplantation 2008;86:399-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan L, Tai BC, Wu F, Raman L, Consigliere D, Tiong HY. Impact of Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines on the prevalence of chronic kidney disease after living donor nephrectomy. J Urol 2011;185:1820-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomic A, Jevtic M, Novak M, Ignjatovic L, Zunic G, Stamenkovic D. Changes of glomerular filtration after nephrectomy in living donor. Int Surg 2010;95:343-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes R, Landray MJ, Winearls CG. Reassuring results with regard to the effect of donor nephrectomy on cardiovascular outcomes. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2009;5:126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Canada. Population by sex and age group, by province and territory. 2010. www40.statcan.gc.ca/l01/cst01/demo31a-eng.htm.

- 15.Von EE, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alter DA, Naylor CD, Austin P, Tu JV. Effects of socioeconomic status on access to invasive cardiac procedures and on mortality after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1359-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin PC, Mamdani MM, Tu K, Jaakkimainen L. Prescriptions for estrogen replacement therapy in Ontario before and after publication of the Women’s Health Initiative Study. JAMA 2003;289:3241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juurlink DN, Mamdani M, Kopp A, Laupacis A, Redelmeier DA. Drug-drug interactions among elderly patients hospitalized for drug toxicity. JAMA 2003;289:1652-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, Kopp A, Austin PC, Laupacis A, et al. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the randomized aldactone evaluation study. N Engl J Med 2004;351:543-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mamdani M, Juurlink DN, Lee DS, Rochon PA, Kopp A, Naglie G, et al. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors versus non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and congestive heart failure outcomes in elderly patients: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 2004;363:1751-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin J, Kramer H, Chandraker AK. Mortality among living kidney donors and comparison populations. N Engl J Med 2010;363:797-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput 2009;38:1228-34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, Normand SL, Streiner DL, Austin PC, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 2005;330:960-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ 2003;326:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, Zhang YL, Beck GJ, Froissart M, et al. Comparative performance of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equations for estimating GFR levels above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 Am J Kidney Dis 2010;56:486-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statistics Canada. Population Groups (28) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census—20% Sample Data. 2011. www.statcan.gc.ca.

- 27.Delmonico F. A report of the Amsterdam forum on the care of the live kidney donor: data and medical guidelines. Transplantation 2005;79(6 suppl):S53-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young A, Storsley L, Garg AX, Treleaven D, Nguan CY, Cuerden MS, et al. Health outcomes for living kidney donors with isolated medical abnormalities: a systematic review. Am J Transplant 2008;8:1878-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ibrahim HN, Rogers T, Tello A, Matas A. The performance of three serum creatinine-based formulas in estimating GFR in former kidney donors. Am J Transplant 2006;66:1479-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg AX, Muirhead N, Knoll G, Yang RC, Prasad GV, Thiessen-Philbrook H, et al. Proteinuria and reduced kidney function in living kidney donors: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Kidney Int 2006;70:1801-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Definition of death and cardiovascular events using valid diagnostic and procedural codes in Ontario healthcare databases