Abstract

Purpose

The study was carried out to report the results of wide resection in sacral chordoma using a posterior approach and gauze packing technique.

Materials and methods

The study was carried out between 1990 and 2002; there were 21 patients who underwent the operation. Fourteen patients were male and seven were female. Their ages ranged between 29 and 75 years. Most of the patients presented with sacral mass, pain and neurological deficit. Total sacrectomy and bone reconstruction were carried out in 12 patients. Subtotal sacrectomy was carried out in the remaining nine patients. All patients were followed up for at least seven years.

Results

All survived after the operation. Operative time ranged between five and ten hours. All patients needed blood transfusion which ranged between four and 11 units. After the operation, all patients had a certain degree of bowel and bladder dysfunction. Five patients had local complications including infection in three patients with wound disruption and two patients with a seroma. During the follow-up, three patients (14%) had tumour recurrence and one of the patients expired. The remaining 18 patients were still tumour-free at the seven-year follow-up.

Conclusion

Wide resection via the posterior approach and gauze packing technique could be used for management of sacral chordoma with acceptable results.

Introduction

Chordoma, a malignant bone tumor, of the sacrum is seldom found. Most patients who have the tumor have a delayed diagnosis. The tumor can destroy the bone extensively. Furthermore, surrounding soft tissue invasion is usually found. Wide resection is still the treatment of choice in chordoma of the sacrum even though most of the patients might subsequently have significant complications [1]. Neurological complications and disability of the patients are the most common complications. The severity and extent of neurological deficit depends upon the level of tumor involvement [2].

In the resection of the tumours, most surgeons use combined anterior and posterior approaches [3, 4]. In the anterior approach, visceral organs can be protected and dissected out from the tumours directly. On the other hand, the posterior approach allows better exploration and protection to neural elements. Furthermore, the posterior approach allows bone reconstruction in total sacrectomy. However, the combined approach is extensive surgery with a prolonged operative time and prolonged recovery of the patient. The posterior approach used on its own has been reported [5]. But this technique was not a commonly used operation as visceral organs and great vessels in the pelvis might have a higher chance of injury during osteotomy. The aim of this study was to present our experience in management of chordoma sacrum by performing a wide resection with a posterior approach only. The technique for protecting visceral organs and great vessels during osteotomy of the bone was achieved by the use of gauze packing under the bones.

Materials and methods

Between 1990 and 2002, 21 patients who had chordoma of the sacrum were treated at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University. There were 14 male patients and seven female patients. Their ages ranged between 29 and 75 years. Twenty patients presented with pain and a mass at their sacrums. One patient presented with a sacral mass without pain or neurological deficit. Twelve patients who had pain and a sacral mass also had neurological deficit and eight patients had neuropathic pain. The patients underwent physical examination and investigation including plain radiograph, MRI and bone scan. After complete investigation, open biopsy was carried out via a posterior longitudinal approach. All biopsies resulted in diagnosis of typical chordoma with moderate to well differentiated tumours.

MRI was used to locate the extent of the tumor. The upper most levels of tumor involvement were L5 in four and S1 in eight patients. Total sacrectomy with instrumentation and bone grafting was done in these 12 patients. Six patients had tumor involvement up to S2, two patients had uppermost lesions at S3 and one patient had the tumor up to S4. Subtotal sacrectomy without bone reconstruction was done in these nine patients. All patients received intra-arterial embolization a day before the surgery to minimize blood loss during the surgery. Pre-operative management was carried out as for a major orthopaedic surgical procedure. Hypotensive general anaesthesia was used in all patients to minimize intra-operative bleeding.

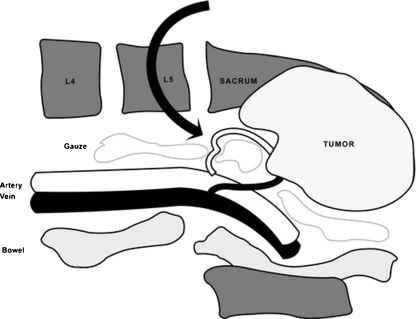

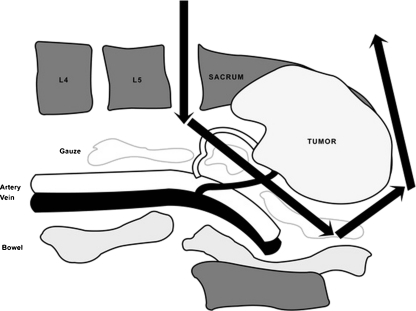

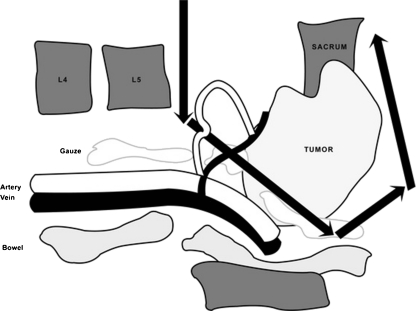

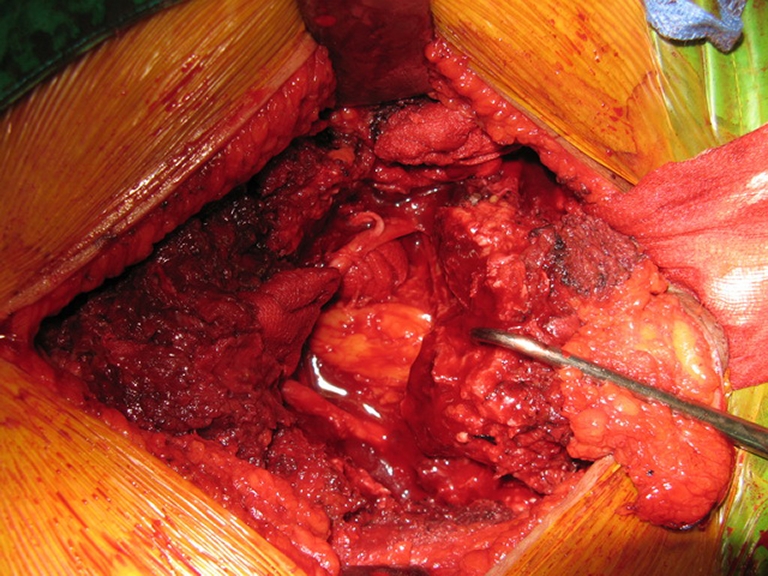

The surgical techniques and steps that we used were as follows. After general anaesthesia, the patient was placed in prone position. The skin was prepared and draped from mid back to buttock and posterior thighs. A median longitudinal incision was performed over the tumor mass starting at about three vertebral levels above the lesion and down to the coccyx. The biopsy scar was dissected out with the tumor mass. With electrocautery, dissection through fascia and muscles was performed down to the bones. During dissection around the tumor, 2–3 cm of gluteal muscles were preserved to provide an adequate tumour-free margin. At the upper end of the incision, dissection was done to identify the spinous processes and lamina of L3 to L5. Both posterior superior iliac spines and posterior inferior iliac spines were identified and dissection was performed to expose the posterior part of both iliac crests, both iliac wings and ala of the sacrum. Dissection was also done along the anterior aspect of the posterior iliac crests. Then, a certain number of rolled gauze swabs with radio-opaque labels were used to pack under the iliac crests and anterior to the body of the lower lumbar vertebra and sacrum (see Fig. 1). Dissection was then carried out along the posterior part of both iliac wings to expose both sciatic notches. At the sciatic notch, the superior gluteal vessels must be identified and protected. With blunt dissection under the rim of sciatic notch, a certain number of rolled radio-opaque gauze swabs were packed under the iliac wing and ala of sacrum. Gauze packing could push the visceral organs and great vessels away from iliac wings, ala of sacrum and the bodies of lower lumbar vertebra and sacrum. These vital organs should be protected during the osteotomy (see Fig. 2). Then a laminectomy was performed starting at L3 or L4, depending on the upper limit of the tumor. All nerve roots were identified and dissected down to the tumor mass. We tried to preserve as many nerve roots as possible. The nerve roots that passed into the tumor mass have to be cut. Then, the margin of resection was re-evaluated carefully by the use of an image intensifier as well as the relationship of bone lesion in the MRI and intraoperative findings. Small Steinman pins were superficially fixed on the iliac wing and the lower lumbar spines which were 2–3 cm away from the tumor margins. They were used to locate the line of the osteotomy to ensure a tumour-free margin. With an osteotome, the normal vertebral body or the disc above the tumor was cut in the postero-anterior direction. Both the posterior iliac crests were cut in the same fashion. Then, a bone hook was placed at the upper surface of the cut vertebra above the lesion and the hook was pulled up to rotate the sacrum and the tumor mass posteriorly (see Fig. 3). With this technique the pre-vertebral space could be explored. The sacral nerves and all feeding vessels of the tumor were dissected out from the tumor. The L5 nerve roots that usually passed closely anterior to the ala of sacrum were identified and protected. This L5 nerve led to the identification of the sacral plexus [6]. All the gluteal muscles above the sacral plexus were cut with electrocautery. Then, exploration of sacral plexus on both sides was carried out. The sacrospinal and sacrotuberous ligaments on both sides were directly identified and cut. At this stage, the cut sacrum with the tumor was easily mobilized to facilitate blunt and sharp dissection between the tumor mass and the visceral organs. After the sacrum and the tumor were removed, all bleeding points were stopped (see Fig. 4). The tumor mass was examined for the free margin and all findings were recorded (see Fig. 5). Bone wax was also used to minimize blood loss from the raw surface of the cut bones. Dacron mesh was use for reconstruction of the urogenital diaphragm.

Fig. 1.

Dissection was done along the anterior aspect of the posterior iliac crests and a certain number of rolled gauzes with radio-opaque labels were used to pack under the iliac crests and anterior to the body of lower lumbar vertebra and sacrum to push visceral organs and great vessels away from the bones

Fig. 2.

Gauze packing could protect visceral organs and great vessels from bone cutting with an osteotome

Fig. 3.

After the body of the upper most vertebra and the iliac wings were cut, the sacrum with the tumor could be rotated backward by the use of a bone hook

Fig. 4.

The cut sacrum with the tumor was easily mobilized to facilitate blunt and sharp dissection between the tumor mass and visceral organs. Furthermore, packed gauze could minimize bleeding

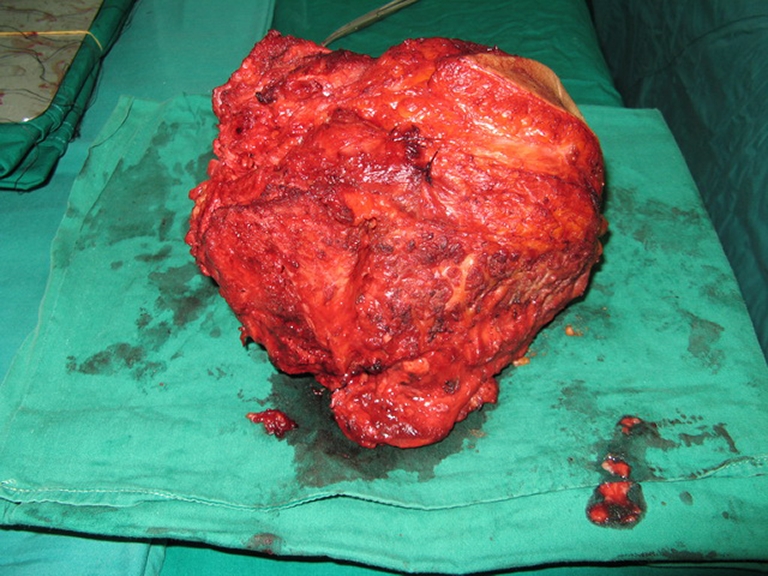

Fig. 5.

The removed tumor was examined for free margin

In the patients who underwent total sacral resection, composite auto-allogenic bone graft and pedicular screw and plate or pedicular screw and rod system were use for stabilization between the ilium and spine. For the patients who underwent partial sacrectomy, all still had enough stability of the axial skeleton so that instrumentation was not applied. The skin and the rest of the soft tissue were repaired. Bulky pressure dressing was done to close the dead space and to minimize blood loss.

On the third day after the operation the surgical wound was examined and pressure dressing was re-applied. Any wound complications were identified and recorded. Neurological signs were re-evaluated. Plain radiograph after the operation was carried out to determine the osteotomy site. All stitches were removed at the end of the second week after the operation.

Histopathological examination of the tumor mass was studied and tumor margin was identified. The criteria of tumor free margin were (1) marginal margin at the ventral aspect of the tumor, (2) there was at least one normal bone or one normal disc which was spared on the tumor side and (3) at least 2 cm of normal muscle and bone were spared on the posterolateral aspect of the tumor. In the patients who did not have tumor margin free as has been mentioned, radiotherapy at the average dose of 3,500–4,500 Gy was administered to minimize local tumor recurrence.

Physical examination including neurological examination of the lower limbs and perianal area, per rectal examination and plain radiograph of chest, sacrum and lower lumbar spine were carried out at each follow-up. During the first two years after the operation, the patient was followed-up every three months. Then, every six months follow-up was carried out between the third and fifth years after the operation. After the fifth postoperative year, the patient was followed-up once a year. MRI of the lumbar spine and sacrum was carried out twice a year during the first two years and then once a year for the later follow-up.

Results

All survived the operation. The operative time ranged between five and ten hours, with an average of 6.4 hours. Average estimated intra-operative blood loss was 1,238 ml, which ranged between 850 and 1,650 ml. The average post-operative blood drainage was 474 ml, which ranged between 300 and 650 ml. All patients needed blood transfusion which ranged between four and 11 units with an average of 7.1 units.

In subtotal sacrectomy, the average operative time was 5.3 hours, ranging between five and seven hours. The patients had an average intra-operative blood loss of 905.55 ml and needed an average blood transfusion of 5.4 units, ranging between four and seven units.

In total sacrectomy, the average operative time was 7.25 hours, ranging between five and ten hours. About one third of the operative time in total sacrectomy was spent on instrumentation after tumor removal. For bone stabilization, a pedicular screw and rod system was used in six patients. In the other six patients, a plate and pedicular screw system was used for bone reconstruction. Average blood transfusion in the patients was 8.5 units and ranged between seven and 11 units.

Infection with skin necrosis was found in three patients. After debridement, local flap and hamstring muscle flap were used for soft tissue reconstruction and all healed satisfactorily. Two patients had a seroma and they responded well after repeated aspiration and pressure dressing. Eleven patients had neuropathic pain after the operation. Eight patients who had neuropathic pain before the operation still had neuropathic pain after the operation. All responded well after anti-neuropathic administration. Visual analog scales of pain severity of the patients ranged between 0.5 and 3 at four months after medication.

From histopathological examination, seven patients had a definite tumour-free margin. The rest (14 patients) had a marginal tumour-free margin at the ventral aspect without tumor contamination. However, the margins at the gluteal muscles were too close, less than 2 cm, ranging between 0.5 and 1.5 cm. Radiotherapy was used in these patients. No significant complication was found in the patients except for one who had radiation colitis. He was a 52-year-old male upon whom total sacrectomy with instrumentation was carried out. He had lower abdominal pain and bleeding per rectum which responded well after symptomatic and supportive treatment.

In the 12 patients who underwent total sacrectomy, their L4 nerve roots could be preserved. However, L5 nerve roots could be preserved only in ten patients. Bilateral L5 nerve roots had to be cut in one and the unilateral L5 root had to be removed with the tumor in another patient. All could not walk without orthotics and five patients were wheelchair ambulators. All patients needed permanent urine bypass by the use of urethral catheterization, and supra pubic cystostomy was carried out in one patient. Regular use of enema and evacuation were carried out in all patients and one needed colostomy.

In the nine patients who underwent partial sacrectomy, L2 nerve roots could be preserved in five patients. These patients could walk normally; however, all needed permanent urethral catheterization for bypassing urine and a regular enema for defecation. One L2 nerve root had to be cut in four patients to provide margin free. These patients could ambulate by the use of foot–ankle orthotics. They also needed permanent urethral catheterization and regular enema.

At the two-year follow-up, none had tumor recurrence. At the three-year follow-up one female patient had local tumor recurrence and re-operation was carried out successfully. The patient was well and without tumor at later follow-up. At the five-year follow-up no patient presented with tumor recurrent or metastasis. At the seven-year follow-up, two patients had tumor recurrence at their pelvises with generalized metastasis, and one patient had passed away because of generalized metastasis of the tumor, including lung and bones.

Discussion

Wide or adequate resection is still the best treatment in chordoma of the sacrum even though most of the patients have permanent neurological deficit after tumor resection [7, 8]. Resecting the tumor as completely as possible will decrease the chances of local recurrence of the sacral chordoma [9]. Rates of being tumor free have been reported to be about 80% at the five-year follow-up after complete resection [10]. The patients who have gross tumor contamination during the surgery have a significantly shorter tumour-free period than the ones who underwent wide resection [11, 12]. In our patients, adequate or wide resection was carried out to lessen recurrence rate and to maximize the tumour-free period by the use of the posterior approach.

Concerning the surgical approach to facilitate adequate tumor resection, it was noted that most authors preferred a combined anterior and posterior approach to provide an adequate approach to the tumor [4, 13]. We have used a combined anterior and posterior approach for wide resection of chordoma of sacrum in five patients from 1987 to 1990. All underwent embolization before the operation and hypotensive anaesthesia was also used during the operation; however, all patients had blood loss over 2,000 ml. We observed that all patients had prolonged operative time, ranging from seven to 13 hours, with a high resulting morbidity. All patients had ileus and severe postoperative pain. Prolonged bed rest and wound complications were also commonly found in the patients. Furthermore, in the patient who had large sacral mass that extended anteriorly and closely to the pubic symphysis, visceral organs and great vessels were usually displaced upward and laterally. The tumor mass usually occupied most of the pelvic cavity and left only a very narrow space for dissection of those visceral organs out from the sacrum and tumor during an anterior approach. We found that only the visceral organs and great vessels, which were above the tumor mass, could be explored easily via the anterior approach. So, we suggested that the anterior approach might not be applicable in the patients who had such a large tumor mass.

We performed a cadaveric study using the posterior approach to explore the sacrum. When the posterior iliac crest and greater sciatic notch were identified, we could pass a certain number of rolled radio-opaque gauzes underneath the ala and the body of sacrum. We found that these gauzes were in between the bones and visceral organs. With a large number of gauzes packing under the bones, all visceral organs and vessels were pushed away from the anterior surface of sacrum and bodies of lower lumbar spines. Packed gauzes could protect those vital organs from bone cutting by an osteotome from the posterior approach. Furthermore, the packed gauze could provide a tamponade effect to intra pelvic venous plexus and result in less intra-operative bleeding. This technique has been used in our patients successfully. None of our patients had injury to their visceral organs or great vessels during bone cutting from the posterior approach. After the bones had been cut, the sacrum and the tumor mass could be mobilized posteriorly at a certain distance and this allowed us to explore and to dissect visceral organs and great vessels out from the tumor easily. Sacral tumours in our patients were removed completely with free margin in seven patients (30%) and none had tumor contamination during the surgery. No visceral organ or great vessel injury in the pelvis and close to the tumor mass was observed. All patients recovered expeditiously after the operation.

Concerning tumor free margin, all specimens were revealed to be marginal tumor free at the ventral aspect of the tumor although the tumor usually extended close to the visceral organs. At the proximal part, all specimens revealed that there was at least one normal bone or one normal disc which was spared on the tumor side. However, 14 patients had less than 2 cm of normal sparing gluteal muscles on the postero-lateral side, even though no gross tumor contamination and a histopathologically tumour-free margin were observed. Radiotherapy was used in these 14 patients. Our findings could be compared to another report concerning adequate safe margins [11–14].

The tumour-free period and tumor recurrence rate of our patients were comparable to other reports. The tumor free period of our patients was 86% at the seven-year follow-up which similar or slightly better than most previous reports which ranged between 56 and 77% [1–5, 11–14]. Tumor recurrence rate in our patients was 14% (3/21) at the seven-year follow-up which was also slightly less than the previous reports, ranging between 26 and 40% [11–14]. The lower tumor recurrent rate in our patients might be the result of both surgical technique and the use of radiotherapy.

All patients in our report needed blood transfusion. The number of blood units used during the surgery and post-operative period ranged between four and 11 units with an average of 7.1 units. This figure was slightly better than some previous reports that indicated blood transfusion of more than eight units was required in most of the patients [4, 5]. However, there was inadequate information about pre-operative embolization in the previous reports and perioperative blood loss. So, the data from our patients might not be comparable to those reports. Using preoperative embolization and gauze packing under the bones to be cut during surgery could lessen intraoperative blood loss. Gauze packing under the bones could provide a tamponade effect on intra pelvic venous plexus and result in less blood loss.

All of our patients had a certain degree of neurological deficit and 11 patients had neuropathic pain. Previous reports did not mention much about the natural history and the management of neuropathic pain after sacrectomy. Neuropathic pain after sacrectomy should be studied in detail as neuropathic pain could unduly burden the patients’ quality of life.

There were five patients who had post-operative complications that required a second operation. The complication rate of our patients seemed to be less than the other reports [1–5, 11–14]. Furthermore, there were no serious complications including great vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or bowel, bladder and great vessels injuries in our patients.

Conclusion

Wide resection of chordoma of sacrum using a posterior approach and large amount of gauze packing under ala and body of sacrum during bone cutting was safe with better results in terms of remaining tumour-free and incurring less blood loss. This technique may be used for other common primary malignant sacral tumours.

References

- 1.Samson IR, Springfield DS, Suit HD, Mankin HJ. Operative treatment of sacrococcygeal chordoma. A review of twenty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(10):1476–1484. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fourney DR, Rhines LD, Hentschel SJ, Skibber JM, Wolinsky JP, Weber KL, Suki D, Gallia GL, Garonzik I, Gokaslan ZL. En bloc resection of primary sacral tumors: classification of surgical approaches and outcome. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3(2):111–122. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.2.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramamurthy R, Bose JC, Muthusamy V, Natarajan M, Kunjithapatham D. Staged sacrectomy—an adaptive approach. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(3):285–294. doi: 10.3171/2009.3.SPINE08824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahakitrungruang C, Chantra K. One-staged subtotal sacrectomy for primary sacral tumor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(9):2594. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0570-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waisman M, Kligman M, Roffman M. Posterior approach for radical excision of sacral chordoma. Int Orthop. 1997;21(3):181–184. doi: 10.1007/s002640050146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waikakul S, Chandraphak S, Sangthongsil P. Anatomy of L4 to S3 nerve roots. J Orthop Surg (HK) 2010;18(3):352–355. doi: 10.1177/230949901001800319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wuisman P, Lieshout O, Sugihara S, Dijk M. Total sacrectomy and reconstruction: oncologic and functional outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;381:192–203. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200012000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen KW, Yang HL, Lu J, Liu JY, Chen XQ. Prognostic factors of sacral chordoma after surgical therapy: a study of 36 patients. Spinal Cord. 2010;48(2):166–171. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Zhu L, Ebraheim NA, Liu X, Castillo S, Tang T, Liu J, Cui H. Analysis of risk factors for recurrence after the resection of sacral chordoma combined with embolization. Spine J. 2009;9(12):972–980. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.08.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferraresi V, Nuzzo C, Zoccali C, Marandino F, Vidiri A, Salducca N, Zeuli M, Giannarelli D, Cognetti F, Biagini R. Chordoma: clinical characteristics, management and prognosis of a case series of 25 patients. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sar C, Eralp L. Surgical treatment of primary tumors of the sacrum. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122(3):148–155. doi: 10.1007/s00402-001-0356-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fourney DR, Rhines LD, Hentschel SJ, Skibber JM, Wolinsky JP, Weber KL, Suki D, Gallia GL, Garonzik I, Gokaslan ZL. En bloc resection of primary sacral tumors: classification of surgical approaches and outcome. J Neurosurg Spinen. 2005;3(2):111–122. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.2.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puri A, Agarwal MG, Shah M, Srinivas CH, Shukla PJ, Shrikhande SV, Jambhekar NA. Decision making in primary sacral tumors. Spine J. 2009;9(5):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed AR. Safety margins in resection of sacral chordoma: analysis of 18 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(4):483–487. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0674-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]