Abstract

Introduction

Research over the past three decades has identified p53 as a multifunctional transcription factor, which regulates the expression of >2,500 target genes. p53 impacts myriad, highly diverse cellular processes, including the maintenance of genomic stability and fidelity, metabolism, longevity, and represents one of the most important and extensively studied tumor suppressors. Activated by various stresses, foremost genotoxic damage, hypoxia, heat shock and oncogenic assault, p53 blocks cancer progression by provoking transient or permanent growth arrest, by enabling DNA repair or by advancing cellular death programs. This potent and versatile anti-cancer activity profile, together with genomic and mutational analyses documenting inactivation of p53 in more than 50% of human cancers, motivated drug development efforts to (re-) activate p53 in established tumors.

Areas covered

In this review the complexities of p53 signaling in cancer are summarized. Current strategies and challenges to restore p53’s tumor suppressive function in established tumors, i.e. adenoviral gene transfer and small molecules to activate p53, to inactivate p53 inhibitors and to restore wild type function of p53 mutant proteins are discussed.

Expert opinion

It is indubitable that p53 represents an attractive target for the development of anti-cancer therapies. Whether p53 is ‘druggable’, however, remains an area of active research and discussion, as p53 has pro-survival functions and chronic p53 activation accelerates aging, which may compromise the long-term homeostasis of an organism. Thus, the complex biology and dual functions of p53 in cancer prevention and age-related cellular responses pose significant challenges on the development of p53-targeting cancer therapies.

Keywords: p53, transactivation, cell death, cell cycle, senescence, Mdm2 inhibitors, p53 gene therapy

1. Introduction

Environmental hazards (e.g., UV sunlight, chemical mutagens, and oncogenic pathogens), and cell-intrinsic metabolic processes can damage DNA. Such damage can alter DNA structure and consequently gene transcription, or can cause mutations that impact gene function. If left unrepaired, DNA damage can cause neoplastic growth [1]. One of the most important response mechanisms to DNA damage involves the p53 tumor suppressor, the so-called “guardian of the genome”. p53 acts as an internal sentinel for DNA damage, and other cellular stresses, including hypoxia, oncogene activation, starvation, altered mitochondrial and ribosomal biogenesis, spindle poisons, or denuded telomeres [1]. Depending on the level of cellular compromise, p53 can induce cell death, senescence, or cell cycle arrest and subsequent DNA repair [1]. Identified in the 1970s as a binding partner for the SV40 tumor virus oncoprotein large T antigen and important target for tumorigenic processes induced by DNA tumor viruses [2–5], research in the late 1980s and 1990s validated p53 as a tumor suppressor gene, as p53 mutations were found in up to 50% of human cancers [6,7]. In addition, Li-Fraumeni patients harboring p53 germline mutations develop cancers with 100% penetrance [8], and p53-deficient mice develop tumors early in life [9]. Mechanistically, p53 acts as a transcription factor that activates and represses a growing number of target genes implicated in cell cycle control (e.g., p21, 14-3-3), apoptosis (e.g., bax, puma, noxa), programmed necrosis (e.g., cathepsin Q), autophagy (e.g., dram), metabolism (e.g., tigar, sco2, glut1, glut4), stem cell homeostasis (e.g., p21), angiogenesis (e.g., thrombosopondin-1), and senescence (e.g., pai-1) [10]. With the molecular elucidation of p53 signaling continuing to unravel novel signaling concepts and broadening our horizon of p53 function and the importance of p53 signaling for the pathogenesis of cancer, drug development programs have begun to target the p53 signaling pathway. In this review, we describe the multi-faceted spectrum of p53 activities, will discuss current strategies to active p53 in tumors, and will conclude with on outlook on future strategies and challenges to implement p53-targeting therapies into clinical practice.

2. The complex biology of p53

Three decades of p53 research produced more than 50,000 publications, which characterized p53 as a transcription factor orchestrating transcriptomic changes in responses to a broad spectrum of cellular stresses. In more recent years, it has become clear that p53 function extends beyond canonical cell cycle, senescence and cell death signaling, and impacts additional, highly diverse biological processes such as programmed necrosis, metabolism, and aging [11]. In addition, multiple studies unraveled transcription-independent functions of p53 that added additional layers of intricacies to an already complex tumor suppressive profile [11].

2.1 Transcription-dependent and independent mechanisms of apoptosis induction by p53 – p53 meets mitochondria and Bcl-2 family proteins

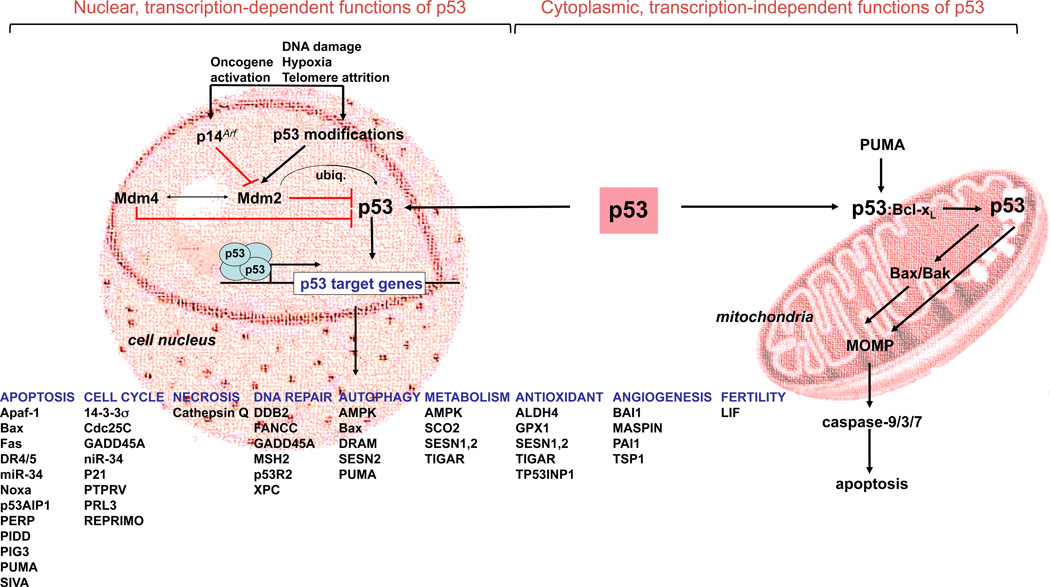

Initial cell culture and animal models with p53 gain- and loss-of-function revealed important pro-apoptotic functions of p53. Specifically, expression of p53 in p53-deficient murine myeloid leukemia cell line potently induced apoptosis [12], and various cell types derived from p53-deficient mice, including mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), thymocytes, and intestinal stem cells were resistant toward a broad range of apoptosis stimuli, including oncogene expression, radiation and chemotherapy [13–15]. Mechanistically, p53 induces apoptosis (a) by transcriptional activation of critical apoptosis regulators of the extrinsic, i.e. death receptor-dependent, and the intrinsic, i.e. mitochondria-mediated apoptosis signaling pathway, and (b) by directly impacting mitochondrial membrane physiology via an intricate interplay with mitochondrial membranes and Bcl-2 family proteins. What are the most critical molecular mechanisms (see Figure 1, nuclear transcription-dependent, and cytoplasmic functions of p53)?

Figure 1. p53 is a tetrameric transcription factor with nuclear, transactivating, and cytoplasmic, apoptogenic functions at the level of mitochondrial membranes.

Activated by a wide variety of different tresses, including oncogene activation (sensed by p14Arf), telomere dysfunction, and DNA damage, p53 transcriptionally induces a broad spectrum of genes implicated in apoptosis, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, autophagy, metabolism, antioxidant signaling, angiogenesis, and fertility. In addition, p53 interacts with Bcl-2 family proteins, and mitochondrial membranes to induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), to trigger cytochrome c release and subsequent caspase activation. Importantly, p53 is regulated by the E3 ubiquitin ligases Mdm2, and Mdm4. Importantly, cytoplasmic and nuclear functions of p53 are intertwined, as Mdm2, a p53 transcriptional target, promotes mitochondrial localization of of p53 through mono-ubiquitination [190], and p53-induced PUMA can release Bax and/or p53 from inhibitory Bax/Bcl-xL and p53/Bcl-xL complexes, to trigger MOMP.

CD95/Fas, and the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptors, DR4 and DR5, have been identified as p53 transcriptional targets [16–18]. Death receptors (DR) are cell surface transmembrane proteins that upon binding their cognate ligands activate the intracellular caspase-8/-10-instigated apoptosis machinery, culminating in direct activation of effector caspases, most importantly caspase-3, -6 and -7, or in amplification of the death signals through the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway [19]. In response to DNA damaging agents, p53 binds an intronic response element within the CD95 gene, and transcriptionally induces CD95 in a variety of different cancer cells, including hepatoma, gastric cancer, colon cancer, and breast carcinoma lines [17]. Similarly, chemotherapy-induced p53 induction drives transcriptional upregulation of DR4 and DR5 [16,18]. Importantly, p53 also induces genes implicated in receptor proximal signaling, foremost caspase-8 [20], and the caspase-8 activator Perp, a tetraspan plasma membrane protein with similarities to the PMP-22/gas family, which is implicated in hereditary human neuropathies [21,22].

DR ligation and initiator caspase activation culminate in cleavage of the BH3-containing protein BH3-interacting domain death agonist (Bid) to generate truncated Bid (tBid). tBid translocates to mitochondria and induces mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), which triggers the release of mitochondrial apoptogenic factors into the cytoplasm [23]. Often referred to as the “point of no return”, MOMP is an irreversible and, consequently, tightly regulated process, which is controlled by an intricate interplay among pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Anti-apoptotic members, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, are embedded into organelle membranes, most importantly the outer mitochondrial membrane, where they can bind their BH3-only pro-death relatives, such as tBid. tBid displaces multi-BH domain-containing pro-apoptotic death agonists, such as Bad and Bax, from a heterodimeric complex with Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL. Once released, Bad/Bax oligomerize and insert into the outer mitochondrial membrane to induce MOMP [24]. Subsequently, mitochondrial proteins, most notably cytochrome c (cyt c), are released into the cytosol where they induce caspase activation. By analogy to membrane-bound DRs acting as scaffold proteins to promote caspase maturation, the apoptotic protease-activating factor (Apaf-1) assembles a cytosolic, multimeric structure to enable caspase-9 activation in the presence of cyt c and ATP. Once activated, caspase-9 activates downstream caspases, most importantly, effector caspase-3 and –7, which in turn selectively cleave and inactivate cellular proteins to induce and propagate cellular demise [23]. p53 transactivates a variety of genes implicated in mitochondrial and post-mitochondrial apoptosis signaling, including Bax [25], PUMA and NOXA [26–29], Apaf-1, and caspase-9 [30] (Figure 1, left panel) to promote mitochondrial membrane disintegration and subsequent caspase activation. In particular PUMA, and to a lesser extant NOXA, appear to be the most critical mediators of p53-driven apoptosis, as deficiencies in these genes recapitulate several key apoptosis phenotypes observed in p53 null mice [31,32]. Most intriguingly, recent studies unraveled transcription-independent, cytoplasmic mechanisms of p53-instigated apoptosis (Figure 1, right panel, cytoplasmic, transcription-independent functions of p53), as p53-instigated death can proceed in enucleated cells [33], does not require de novo RNA synthesis and translation [34], and can be genetically dissected from p53-driven transactivation programs [35]. Chipuk et al. [36,37] linked p53-directed transcriptomic changes of apoptosis modulators to cytoplasmic, transcription-independent functions of p53, as p53-dependent genotoxic insult induced PUMA, which subsequently displaced p53 from an cytosolic, inhibitory p53:Bcl-xL complex. Liberated p53 subsequently bound and activated Bax to trigger MOMP. Additional models suggest that p53 can physically interact with Bcl-2/Bcl-xL to release Bid and instigate Bid-mediated activation of the multi BH domain proteins Bax and Bak [38], or can form an activating complex with Bak, thereby disrupting a Bak-inhibitory Bak:Mcl-1 interaction [39] (Figure 1, right panel). Finally, the atypical Bcl-2 family protein Bcl-2-Like12 (Bcl2L12), a XIAP-like inhibitor of effector caspase activation [40–42], was recently identified as a nuclear protein, which attenuated the transactivational activity of p53. Mechanistically, Bcl2L12 bound p53, prevented it from binding promoter elements of its transcriptional targets, e.g., p21, DR5, PUMA, and NOXA, and reduced p53 protein stability [43,44].

In addition to caspases 8 and 9, p53 also regulates apoptosis initiation by caspase-2, which does not directly activate executioner caspases, but induces MOMP to propagate programmed cell death [45]. Similarly to caspase-activating DR and apoptosome structures, the caspase-2 activation platform is a multimeric protein complex termed the PIDDosome consisting of p53-induced protein with death domain (PIDD), RIP associated Ich-1/CED homologous protein with death domain (RAIDD), and caspase-2 [46]. Basal and radiation-induced levels of PIDD correlated with p53 expression in MEFs, and accordingly, p53 transcriptionally induce PIDD via binding to responses elements upstream of the transcriptional start site [47].

2.2 p53 and programmed necrosis

In addition to its well-documented roles in apoptosis signaling, p53 has recently been implicated in programmed necrosis. Also referred to as autolysis, oncosis, pyroptosis, necraptosis, and necroptosis, the concept is that necrosis is a genetically regulated, cell autonomous process [48]. Similar to enhanced proliferative capacity and apoptosis resistance as hallmark features of cancer, tumor cells have acquired mutations that function to induce an irreversible bioenergetic crisis. In response, cells die through necrosis and, in the process, release gene products into the extracellular space to trigger a plethora of pro-tumorigenic host responses [49]. Several laboratories hypothesized that necrosis is initiated by a distorted vasculature and intratumoral hypoxia, and supported or sustained by tumors cells genetically predetermined to undergo programmed necrosis. Recent evidence suggest that the tumor suppressive activity of p53 might in part relate to its capacity to drive programmed necrosis, as p53 transactivates cathepsin Q in response to DNA damage in apoptosis-deficient Bax/Bak double knock out cells [50]. Cathepsin Q is a lysosomal protease that upon lysosomal membrane permeabilization leaks into the cytosol, where it cooperates with reactive oxygen species (ROS) to digest cellular substrates and induce programmed necrosis [50].

2.3 p53 and the control of cell cycle progression and DNA repair

Besides orchestrating transcription-dependent and independent cell death programs, p53 has pivotal functions in cell cycle progression, as it regulates G1/S, S, and G2/M cell cycle checkpoints [51]. Cell cycle progression is driven by cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks), including cyclin D/cdk4, cyclin E/cdk2, and cyclin A/cdk2 complexes, which sequentially phosphorylate tumor suppressors of the Rb family, resulting in activation of E2F-driven transcriptional programs to instigate DNA replication [52]. Central to the cell cycle inhibitory function of p53 is its capacity to transcriptionally upregulate the cdk inhibitor p21 (CIP1/WAF1), which upon induction localizes to the nucleus of DNA-damaged, p53 proficient, but not p53 mutant cells, binds to and inhibits cyclin E/cdk2, and cyclin A/cdk2 complexes, halts cell cycle progression and DNA replication, and allows for DNA repair [53,54]. Critical roles for p21 in G1/S transition have been validated in p21-deficient MEFs and colon cancer cells, exhibiting deficiencies in DNA damage-induced G1 arrest [55–57].

Extending the role of p53-mediated p21 induction in G1 cell cycle arrest, the p53-p21 signaling axis appears to be instrumental for maintaining S phase checkpoints [51], with some suggestions that an alternatively spliced, and apoptosis-deficient p53 isoform, Δp53, is responsible for inhibiting S phase progression via selective induction of p21 and 14-3-3σ [58].

In addition, p53 also impacts the G2/M checkpoint by transcriptionally modulating the expression of multiple, physically and functionally intertwined targets, including Cdc25C, 14-3-3σ, p21, and GADD45 [51]. Mechanistically, p53 represses Cdc25C [59], a mitosis-promoting phosphatase, which dephosphorylates and activates the cyclinB1/cdc2 complex as a critical executioner of the G2/M arrest. In addition, Cdc25C can be inhibited by Chk1 and Chk2-mediated phosphorylation. Such modification of Cdc25C triggers complex formation with 14-3-3 proteins, which are transcriptionally induced by p53 [60]. A Cdc25C;14-3-3σ complex is sequestered in the cytosol and enzymatically inactive. 14-3-3σ also prevents nuclear localization of the cyclin B1/cdc2 complex. While the contribution of p21 to the G2/M checkpoint arrest is controversially discussed [51], some studies suggest that p21 can inhibit cyclin B1/cdc2 complex activity through physical interaction, thereby displacing Cdc25C from an activating Cdc25C:cyclinB1/cdc2 complex [61], by retaining cyclin B1/cdc2 complexes in the nucleus [62], and by blocking activation of cdc2/cyclin B by CAK [63]. Finally, p53-induced GADD45 inhibits the cyclinB1/cdc 2 complex via interaction with and inhibition of the cdc2 kinase activity [64,65].

In addition, p53 modulates the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) to ensure proper chromosome segregation during anaphase and to prevent aneuploidy. SAC detects misalignments of chromosome at the cell equator and failure to attach chromosomes to microtubles of the mitotic spindle, and subsequently initiates Mad protein-dependent inactivation of the anaphase promoting complex (APC) [66]. Consistent with a role of p53 in SAC control, p53-deficient MEFs exhibited defects in cell cycle arrest upon treatment with microtubule inhibitors [67,68], and contained abnormal number of centrosomes [69]. Similar to p53-dependent, DNA damage-induced G1 arrest, p53-driven SAC control involves p21 [70].

In addition to its multi-faceted roles in cell cycle checkpoints, p53 also impacts DNA repair to maintain genomic integrity via physical interactions with and transcriptional induction of critical DNA repair proteins. p53-instigated DNA repair mechanisms involve (a) upregulation of GADD45, which subsequently binds to PCNA, the DNA polymerase ™ loading, and processivity factor [71] to promote DNA excision repair [72], (b) interaction with several protein involved in replication, homologous recombination and nucleotide excision repair, including replication protein A (RPA) [73], and (c) intrinsic activities of p53, e.g., DNA-reannealing and DNA end-joining activities, DNA strand transfer, and a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity [51].

2.4 p53 regulation of metabolic pathways

In 1902, the German geneticist Theodor Boveri hypothesized that human cancers are caused by genomic aberrations converting normal cells into incessantly dividing tumor cells. By extension, Otto Warburg proposed, in the 1920s, that tumor cells exhibit defects in mitochondrial energy metabolism to adapt to the increased demands of limitless proliferation. Boveri’s concepts of cell cycle check points, oncogenes, and tumor suppressors, and Warburg’s idea of metabolic adaptation to cancerous transformation ignited the field of cancer genetics and metabolics to elucidate the molecular underpinnings of malignant initiation and progression. Today, more than 100 years after the seminal discoveries of Boveri and Warburg, the idea that tumorigenesis and altered metabolism are intertwined (“metabolic transformation”) is more relevant than ever. Cancer-causing mutations can drive metabolic changes, which in turn, confer growth advantages and/or resistance to apoptosis. In contrast to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence as p53-directed processes in response to extensive (cancer-associated) insult, recent evidence suggests that p53 plays important roles in regulating cellular metabolism, in particular when cells are exposed to low-level stresses [74]. Specifically, p53 promotes oxidative phosphorylation with some suggestion that enhanced respiratory functions decreases tumor-promoting glycolysis [75]. In addition, p53 is implicated in maintaining mitochondrial mass and genome integrity [76,77], transcriptionally activates proteins involved in respiratory functions, including cytochrome c oxidase 2 (SCO2) [78], and subunit I of cytochrome c oxidase [79]. In addition, p53 inhibits glycolysis via multiple mechanisms, including (a) downregulation of glucose transporters through direct transcriptional repression (glut1 and glut4) [80], and through inhibition of the NFκB-IKK signaling axis (glut3) [81], (b) ubiquitination and inactivation of the glycolytic enzyme phosphoglycerate mutase (PGM) [82], and (c) transcriptionally upregulation of TIGAR, a fructose 2,6 bisphosphatase (FBPase) [83,84]. In addition to this dual impact on oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis, p53 also activates the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) to supply cells with NADPH for reductive biosynthesis reactions, and ribose-5-phosphate (R5P) for the synthesis of nucleotides and nucleic acids. Mechanistically, p53 may drive PPP activation via concomitant upregulation of hexokinase 2 to initiate PPP, and via induction of TIGAR to inhibit phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK1) and consequently glycolysis [85]. Interestingly, hypoxia-induced downregulation of ribonucleotide reductase and subsequent PPP inhibition activate p53 [86], suggesting that a positive feedback loop sustains PPP to promote cell survival, and to repair low-level damage in response to normal growth or moderate stress.

In addition to the p53-TIGAR signaling arm, additional p53-instigated survival programs have been identified that protect cells toward reactive oxygen species (ROS), including p53-dependent activation of sestrins [87], p53INP1 [88], and the p21-Nrf2 axis as a master regulatory pathway orchestrating complex antioxidant gene expression [89]. Importantly, p53 can also induce ROS to promote apoptosis, and senescence, e.g. via upregulation of PUMA, NOXA, and PIG3. Ongoing research to unravel the molecular basis of these divergent activities of p53 hypothesizes that extent and duration of cellular stresses determines, whether p53 induces and or inhibits ROS production. High-stress levels favor ROS induction and cell death, moderate stresses induce ROS-antagonizing functions of p53 to repair damage and promote cell survival [11].

2.5 p53 and cellular senescence – transient versus permanent, irreversible cell cycle arrest

Contrasting mechanisms to transiently halt cell cycle progression described above, cellular senescence is an irreversible form of cell cycle arrest [90], which restrains neoplastic growth [91]. Similar to transient cell cycle arrest, an intricate interplay of p53-p21 and p16INK4a-Rb-E2F signaling axes is most critical for driving senescence. Here, p14Arf can act as a sentinel for senescence-inducing signals (e.g., telomere erosion, non-telomeric DNA damage, perturbations in chromatin organization, and oncogene hyperactivation), to stabilize p53 by Mdm2 sequestration (Figure 1). Subsequently, p53 transcriptionally activates p21 to induce senescence rather than transient cell cycle arrest [92]. What are the molecular parameters that determine the cellular fate of transient cell cycle arrest versus senescence? It may depend on additional signals that cooperate with p53, such as Rb-induced senescence-associated heterochromatin foci to silence E2F target genes, as co-activation of Rb-E2F and p53 axes permanently block cell cycle progression [93,94].

Further molecular analyses of p53-instigated senescence programs revealed non-cell autonomous roles of p53, as p53 modulates the secretome of senescent cells by upregulating immune-modulatory cytokines, and modulating the extracellular matrix [95,96]. This p53-driven secretory phenotype contributes to the overall tumor suppressor profile of p53, as p53 restoration in liver tumors induced senescence and resulted in potent induction of the innate immune response to halt tumor growth [96]. Due to the impact of p53 on senescence, p53 deletion in cancers may not only trigger unabated tumor growth, but may also compromise immune surveillance mechanisms.

2.6 p53, aging, and stem cells

Cancer is an age-related disease [97,98]. Consequently, genes that stop cancer progression, such as p53, promote longevity by restraining genomic instability, and inhibiting the growth and expansion of genetically aberrant cells. Excessive p53 tumor suppressive activity, however, can be detrimental to organismal homeostasis by promoting certain aspects of aging. When does too much of a good thing become a bad thing?

Maintenance and regeneration of adult tissues, and consequently longevity depend on the continuous proliferation and differentiation of resident stem cells [99,100]. In line with a tumor suppressive, pro-death and anti-proliferative role of p53, deficiency in p53 was shown to attenuate profound defects in tissue homeostasis caused by mutations in DNA repair genes [101]. In addition, mice expressing a carboxy-terminal, constitutively active p53 mutant exhibited a premature aging phenotype, including organ atrophy, osteoporosis, and reduced life span [102]. Such excessive decline of organ function due to the exacerbate and chronic activation of p53, has been linked to the depletion of adult tissue stem cells [103]. Sharply contrasting these studies, bacterial artificial chromosome-transgenic mice harboring a single copy of p53 (or Arf) resulting in moderately elevated levels of p53 and Arf, exhibited increased life span with reduced tissue damage, elevated antioxidant gene expression. These studies suggest that moderate p53 activation is beneficial for tissue homeostasis [104,105], as chronic hyperactivation of p53 decreases longevity, while moderate, physiological enhancement of p53 activity with intact regulatory mechanisms to control p53 stability, induces an anti-aging phenotype. It appears that duration and extent of stress and consequently levels p53 activity determine cell and organismal fate; high p53 activation restricts proliferation, low levels induce cell survival, and decrease oxidative damage via induction of an antioxidant gene signature.

3. Impact of p53 restoration on cancer initiation and progression – lessons learned from murine cancer models

Murine cancer models employing p53-targeting RNA interference, a 4-hydroxytamoxifen-inducible p53 knock-in, and a Cre-reactivatable p53 knockout allele harboring a transcription–translation stop cassette flanked by loxP sites, have been described recently. These models are engineered to reversibly reinstate p53 in established, oncogene-driven murine lymphomas, sarcomas, and liver carcinomas. Confirming important roles of p53 in cancer suppression, these studies showed that reactivation of p53 in established tumors can temporarily stop tumor growth; the precise cellular mechanism is cancer type-specific, as lymphomas die by apoptosis, whereas p53 restoration in sarcomas and liver carcinomas leads to growth arrest and senescence [96,106,107]. p53-driven apoptosis and senescence responses associated with temporary p53 reactivation led to prolonged survival. Although cancer remission was not permanent, and p53-resistant tumors emerged, possibly via inactivation of p19Arf or Mdm2 activation, these studies clearly reinforced the potential of p53 inhibition to halt tumor progression. More recent studies using a KRas-driven models of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), however, documented that p53 reinstatement only affected the more advanced adenocarcinoma lesions, while growth rates of early, hyperplastic lesions were not impacted by p53 [108,109]. It is plausible that low oncogenic stress in early lesions, together with low or undetectable levels of the p53 activator p19Arf are insufficient to activate p53; advanced lesions, however, which exhibit high oncogenic stress levels due to amplification of mutant, and loss of endogenous KRas, together with additional genomic/genetic alterations in other components of the Ras-MAPK signaling arm, can induce high levels of p19Arf to activate p53. These lesions are dependent on sustained p53 inactivation to progress, and consequently die or arrest upon p53 reactivation. These murine cancer models also reinforce the notion that p53 elicits tumorsuppressive functions, i.e. cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, when cellular homeostasis is compromised by high stress levels. In response to low-level assaults, with signal strengths comparable to pathway activation under physiological conditions, p53 is not activated, as p53-driven cell cycle inhibitory and pro-death functions would compromise normal tissue maintenance and regeneration as discussed above. Finally, these studies also suggest that p53 reactivation would only affect more malignant tumors with high oncogenic flux. The majority of human cancers is diagnosed in a more advanced state, and could therefore benefit from p53 targeting therapies. It is important to stress, however, that hyperplastic lesions are still present; they can advance to a more malignant state, suggesting that continual p53 targeting might be necessary to control tumor progression.

4. Targeting p53 signaling for cancer therapy

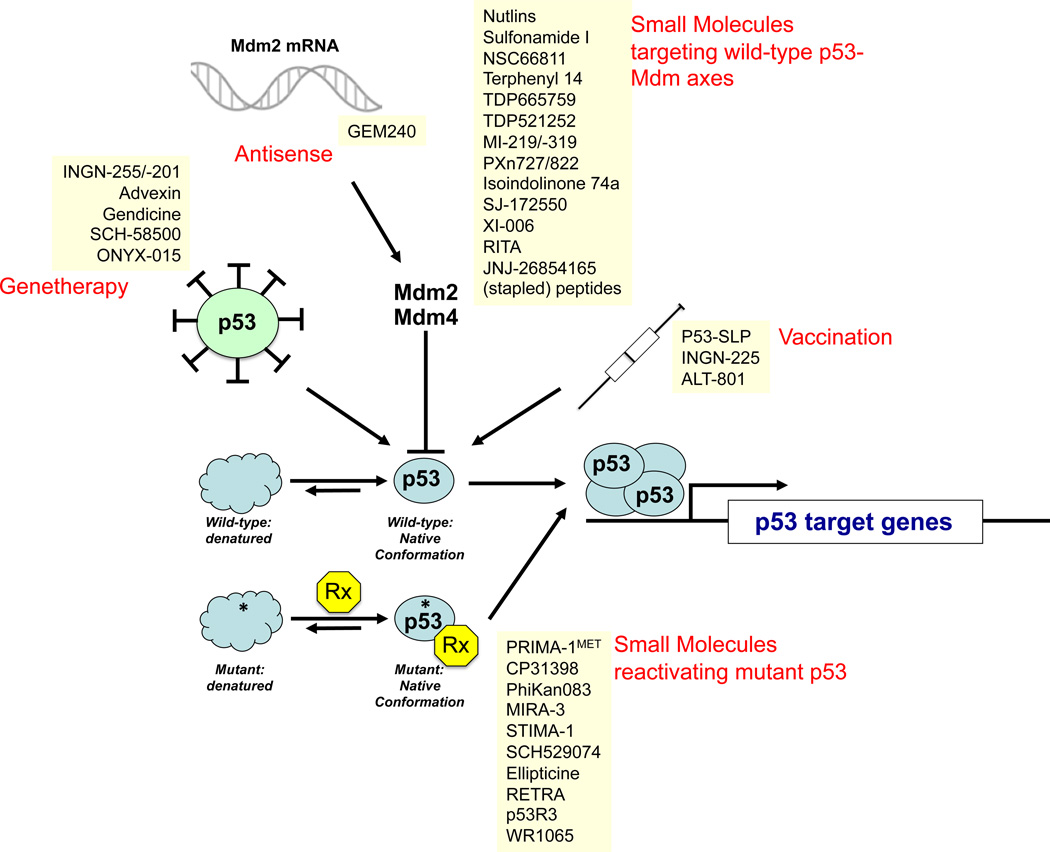

The tumor suppressor p53 plays critical roles in cancer pathogenesis and therapy (apoptosis) resistance and, consequently, represents a vital cellular drug target. Importantly, p53 is inactivated in 50% of human cancers, and components of the p53 signaling pathway, e.g., Mdm2 and p14Arf, are often misappropriated in the other 50% of cases. In addition, molecular epidemiological analyses revealed that several cancers, including breast, head and neck, liver, and hematopoietic malignancies, showed a significant association of TP53 mutations with worsened patient survival (for detailed review of p53 abnormalities as biomarkers for cancer risk and prognosis, see [7]). Based on the paramount importance of p53 for tumorigenesis, several strategies have been developed to restore p53-instigated cell cycle-inhibitory, pro-apoptotic, and pro-senescence functions in p53 mutant cells and tumors. These have employed gene therapy methodologies using adenoviral p53 expression vectors, or small-molecule-/peptide-based approaches to functionally reactivate mutant p53, and to block molecular targeting of p53 by chaperone and ubiquitin ligases to prevent its proteasomal degradation. Here, we summarize p53-targeting strategies that are in pre-clinical or clinical development, or represent novel approaches to incapacitate p53 signaling in human cancers. More than 150 clinical studies are listed in the clinical trial database of the National Cancer Institute (http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/), which aim to assess the p53 status of patients to optimize drug and radiation regimens, and to evaluate p53 gene transfer and Mdm2 blockage to restore the tumor suppressive activity of p53. Figure 2 and table 1 summarize p53-targeting therapeutics currently in preclinical and clinical development.

Figure 2. Therapeutics targeting the p53-signaling pathway.

Depicted are the five classes of p53-targeting therapeutics, i.e., genetherapeutic agents to delivery p53 via adenoviral transduction into p53-deficient cancer cells; anti-sense oligonucleotides targeting Mdm2; small molecules targeting wild-type p53 (i.e., compounds that liberate p53 from a inhibitory p53:Mdm24 complexes); small molecules targeting mutant p53 to restore its native conformation, and transactivational activity; and vaccination approaches (i.e., p53-SLP, a mixture of overlapping p53 peptides representing amino acids 70 to 248 used in conjunction with montanide, a water in oil emulsions as adjuvant; INGN-225, a vaccine utilizing p53-peptide transfected dendritic cells; and ALT-801, an interleukin-2-T cell receptor fusion protein directed against MHC-presented p53 peptides). RITA, reactivation of p53 and induction of tumor cell apoptosis; PRIMA, p53 reactivation and induction of massive apoptosis-1; MIRA-3, mutant p53 reactivation and induction of rapid apoptosis; STIMA, SH group targeting and induction of massive apoptosis; RETRA, reactivation of transcriptional reporter activity.

Table 1.

Most prominent p53-targeting therapeutics in (pre-)clinical development.

| Type | Therapeutics | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Genetherapy using adenovirally delivered p53 | Gendicine, SCH-58500, INGN-201 | Phase IV (in China) |

| Advexin | Phase I/II | |

| Vaccination | P53-SLP | Phase II |

| INGN-225 | Phase I | |

| ALT-801 | Phase I/II | |

| Mdm2 antagonists | Nutlin | Phase I |

| MI-219 | Preclinical | |

| RITA | Preclinical | |

| JNJ-26854165 | Phase I | |

| PXn727/822 | Preclinical | |

| Reactivation of mutant p53 | PRIMAMET/APR-246 | Phase I/II |

| CP-31398 | Preclinical | |

| MIRA-1 | Preclinical | |

| STIMA-1 | Preclinical | |

| Mdm2 antisense | GEM240 | Preclinical |

| Cyclotherapy | Nutlin + BI-2536 | Phase I |

| Nutlin + VX680 | Phase I |

4.1 Genetherapy to restore p53 function

Several studies demonstrated that adenoviral delivery of wt p53 (Ad-p53) triggers a dramatic apoptosis response in cell culture and tumor regression in rodents with subcutaneously and orthotopically implanted cancers, e.g. gliomas [110–114]. The clinical potential of Ad-p53 (Gendicine, Shenzhen Sibiono Genetech, China; ADVEXIN, Introgen Therapeutics, Inc) was tested in phase I studies for the treatment of patients with recurrent malignant gliomas [115]. Intratumoral injection of Ad-p53 resulted in expression of a functionally active p53 protein as assessed by apoptosis induction and p21 upregulation, and was associated with minimal toxicity. The distribution of exogenous p53, however, was limited to the injection site without demonstrable, more pervasive intratumoral dispersal. Consequently, p53 gene delivery did not significantly impact progression-free or overall survival rates [115], thus requiring different strategies to more effectively deliver p53 into tumor cells. Additional efforts to evaluate p53-based gene transfer include clinical studies in patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [116], and ovarian cancer with adjunct chemotherapy [117]. While the ovarian cancer trial did not reveal any therapeutic effect of adenovirally delivered p53, studies in head and neck cancer[118,119], and hepatocellular carcinomas [120,121] revealed a statistically significant increase in time to progression in patients with p53 wildtype alleles. Encouraging responses of replication-incompetent adenoviral p53 constructs in Li-Fraumeni patients [122], yet failure to prove a more general efficacy, may point to ineffective patient stratification based on biomarkers predicting responsiveness toward p53 reactivation. More recent efforts elucidated combination therapies of gendicine and epirubicin hydrochlorid (EPI) in gastric cancer [123], and combinatorial Ad-p53 and radiation regimens for patient diagnosed with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinomas [124]. These and addition studies assessing intraepithelial injections of Ad-p53 for the treatment of oral leukoplakia, a precancerous lesion of squamous cell carcinomas [125], and bronchoalveolar lavage of Ad-p53 in patients with bronchioalveolar cell lung carcinoma [126], pointed to tumor inhibitory effects of Ad-p53, in particular in combination with chemo- and radiation therapy, and warrant further, in-depth clinical assessment. Additional efforts have been directed toward the characterization of more advanced vector systems [127], most importantly of oncolytic, conditionally replicating adenoviruses (CRAs) that only replicate in p53-dysfunctional tumor cells [128–130]. ONYX-015/dl1520 is the most prominent, and clinically evaluated CRA, which has been generated by deleting the p53-inhibitory protein E1B55kDa from the viral genome. Patients diagnosed with malignant glioma [131] and head and neck cancers [118] tolerated the virus well. Due to only moderate potency, inefficient systemic delivery, and limited intratumoral dissemination, multiple phase II/III clinical trials failed to demonstrate single-agent activity of ONYX-015, and synergistic effects with a wide spectrum of chemotherapeutic agents, e.g., cisplatin, 5-FU, doxorubicine, and gemcitabine [132]. To overcome the limited clinical applicability of oncolytic vectors, recent preclinical studies developed mesenchymal (MSCs), and neural stem cells (NSCs) as delivery vehicles for CRAs, in particular for the treatment of malignant glioma [133,134]. These novel delivery strategies are awaiting further evaluation in early phase I/II clinical trials.

4.2 Small molecule-based approaches to target the p53-Mdm2 axis

The E3 ubiquitin ligase Mdm2 is one of the most critical regulators of p53. Mdm2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets p53 for mono- and poly-ubiquitination Monoubiquitination mediated by low levels of Mdm2 promotes mitochondrial localization of p53, and elevates nuclear export of p53 to block its transactivational activity; high Mdm2 levels promote polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-dependent degradation of p53 [135]. Reflecting its importance as a negative p53 regulator, Mdm2 is frequently amplified in human cancers [136]. The p53-Mdm2 interaction is controlled by transcriptional mechanisms, post-translational modifications and complex formation with additional, regulatory proteins. These include (a) transcriptional induction of Mdm2 by p53, (b) p53-dependent upregulation of the Mdm2 inhibitor p14Arf, (c) ATM, ATR, DNA-PK and Chk1/2-mediated phosphorylation of p53, (d) complex formation of Mdm2 with Mdm4, and (e) modulation of p14Arf mRNA levels by TWIST, Tbx-2, and Bmi1 [137].

The importance of the p53-Mdm2 axis in cancer prompted cell culture-based and xenograft studies, which confirmed potent cytostatic, pro-apoptotic and tumorsuppressive functions of small molecule-based and polypetidylic inhibitors of Mdm2, foremost Nutlin-3 [138], and MI-219 (AT-219; Ascenta Therapeutics, Malvern, PA, USA) [139].

Nutlin-3, a cis-imidazoline mimicking critical residues in the transactivation domain of p53 essential for Mdm2 binding (i.e. Phe19, Trp23, Leu26), is the best-studied Mdm2 antagonists [140]. Preclinical data in hematological, neurological and malignant bone cancers revealed potent pro-apoptotic, anti-tumorigenic and anti-metastatic functions with only subtle adverse side effects [141]. This favorable activity profile likely reflects the capacity of nutlin-3 to induce apoptosis, inhibit authophagy, and promote pro-senescence responses selectively in tumor elements, but not normal cells, where nutlin-3-mediated Mdm2 blockage is linked primarily to cell cycle inhibition [141]. Tumor-selective killing by nutlin-3 is dependent on wildtype p53, as p53 mutant AML and neuroblastoma cells are resistant toward nutlin-3-associated cytotoxic effects [142]. Importantly, nutlin-3 shows synergism with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs, including doxorubicin and cytarabine, radiation, TRAIL, and inhibitors of XIAP, γ-secretase, Cdks, JNK, PI3K, and aurora kinases, pointing to the possibility of combinatorial therapies for the treatment of advanced stage blood, brain and bone cancers [141]. A more detailed molecular understanding of cellular responses elicited by nutlin-3 treatment is beginning to emerge, and will aid in optimizing drug combinations for preclinical and clinical testing. Recent reports documented that nutlin-3 treatment lead to p53-dependent upregulation of Notch1 in leukemia and CLL B cells [143]. Notch-1 activates the PI3K-mTOR signaling pathway, which in turn limits pro-death activities of p53. Consequently, the rational combination of nutlin-3 with the γ-secretase inhibitors DAPT and L-685458 potentiated nutlin-3 action [143]. A similar enhancement of nutlin-3-mediated apoptosis was observed, when it was combined with the effector caspase inhibitor XIAP. XIAP inhibition promoted caspase-driven proteolytic degradation of anti-apoptotic p21, which in turn sensitized cells toward caspase-6- mediated cell death [144]. Finally, nutlin-3 does not only induce tumor-cell specific apoptosis, but is also implicated in pro-senescence responses, as nutlin-3 treatment was shown to potentiate tumor regression induced by Pten-loss induced cellular senescence (PICS) [145].

The spiro-oxindole MI-219 represents a second class of Mdm2 inhibitors, which similar to nutlin-3, blocks the interaction of p53 with Mdm2 by mimicking critical residues of the p53-Mdm2 complex interface [146]. Consequently, MI-219 and MI-319 triggered apoptosis in p53 wildtype, but not p53 mutant cells, induced tumor regression, in particular in lymphoma mouse models, provoked little systemic toxicity, and showed synergism with DNA damage-inducing agents ([141]; see Figure 2 for additional Mdm2 inhibitors, which include sulfonamide I (NSC279287; CAS 59541-35-4)[147], the quinolinole NSC66811 (CAS 6964-62-1)[148], terphenyl 14 [149], TDP521252 and TDP665759 [150], the PXn series of Mdm2 inhibitors [151], and isoindolinones [152,153]).

4.2.1 Mdm2 inhibitors and cyclotherapy

Mdm inhibitors showed low systemic toxicity, and a highly differential impact on tumor versus non-tumor elements, as cancerous cells undergo p53-dependent apoptosis, and normal cells exhibit transient cell cycle arrest. Consequently, nutlin-3, and MI-219 are emerging as drug candidates for cyclotherapy. The concept is that chemotherapy only kills continuously cycling tumor cells; normal cells with low proliferative capacity will undergo transient cell cycle arrest, and after drug withdrawal, will re-enter the cell cycle without measurable cytotoxic effects [154]. Consequently, combinatorial treatment regimes of nutlins and chemotherapeutic drugs, such as paclitaxel, have been evaluated in p53 mutant tumor versus normal cells with wildtype p53 alleles. Here, nutlin treatment caused p53-dependent cell cycle arrest in normal, but not cancerous cells; second line treatment with cytarabine, the aurora kinase inhibitor VX-680 (Vertex Pharmaceuticals, USA), paclitaxel, or polo-like kinase inhibitor BI-2536 (Boehringer Ingelheim, UK) caused apoptosis in tumor cells, while sparing cell cycle-arrested, and consequently drug-resistant normal cells [154]. Preclinical testing of sequential Mdm2 and polo-like kinase inhibition in xenogeneic grafts revealed dramatic reduction in neutropenia, a common side effect of chemotherapy, without limiting chemotherapy-induced, tumor cell-specific apoptosis [155]. The challenges for translating cyclotherapy into the clinic are obvious: First, Mdm2 inhibitors with potent activity upon systemic administration in patients have to be identified, as nutlins may lack sufficient potency for sustained Mdm2 inhibition. Second, further preclinical testing is required to determine the most appropriate drug combinations, and the most effective sequence and timing of Mdm2 inhibitor and chemotherapy regimens.

4.3 p53-based vaccination

Besides gene therapy and small-molecule based approaches to reinstate p53 activity, a radically different approach has entered early phase I/II clinical trials, which employs vaccination with p53-dervied peptides. Due to high expression levels and frequent mutation of p53 in human cancers, p53 is immunogenic, as cancer patients produce p53 autoantibodies and p53-reactive CD4 and CD8 T cells [156]. The most advanced clinical validation of this technology includes (a) vaccination with a mixture of synthetic p53-dervied peptides (p53-SLP; ISA Pharmaceuticals, Bilthoven, the Netherlands) for the treatment of colorectal cancer [157], and (b) dendritic-cell delivered p53 vaccines resulting from transduction of dendritic cells with a modified p53 adenovirus for patients with small-cell lung cancer (INGN-225, Introgen) [158].

4.4 Small molecules to rescue mutant p53 function

With more detailed insights into the structure and regulation of p53 wildtype and mutant proteins, small molecules have been developed to restore wildtype function of mutant p53 proteins. PRIMA-1 (p53 reactivation and induction of massive apoptosis-1), and its optimized derivative PRIMA-1MET, were identified as compounds that specifically inhibited the growth of p53 mutant tumor cells [159,160]. Mechanistically, the PRIMA-1 decomposition product methylene quinuclidinone functions as a Michael acceptor to alkylate cysteine residues within the DNA binding domain of the p53 polypeptide [161]. Similarly to MIRA-3 (mutant p53 reactivation and induction of rapid apoptosis), and STIMA-1 (SH group targeting and induction of massive apoptosis), which also rescue mutant p53 function via thiol modification within the DNA binding domain, PRIMA-1 increased p53 activity by restoring sequence-specific DNA binding, and triggered the mitochondria-dependent intrinsic apoptosis program via activation of caspase-2 [162]. Xenograft studies using lung and osteosarcoma cell lines have documented potent anti-tumorigenic activity of PRIMA-1 alone or in combination with cisplatin, without adverse systemic side effects [160,163,164], and motivated early-stage clinical trials with APR-246, a structural PRIMA-1 analog [165].

In addition, in silico screens with more than 2.5 million compounds identified the carbazole PhiKan083 (1-(9-ethyl-9H-carbazole-3-yl)-N-methylmethanamine) as a small molecule that selectively interacted with and stabilized the p53 Y220C mutant, one of the ten most prevalent p53 mutations targeting the DNA binding domain [166]. While detailed biological data assessing the impact of PhiKan083 on p53 function are still elusive, physico-chemical, and structural characterization of the PhiKan083-p53Y220C complex catalogued conformational changes, and revealed a significant increase in melting temperature and half life of the Y220C mutant polypeptide upon complex formation with the drug [167]. Additional compounds targeting mutant p53 include (a) CP31398, which increased mutant p53 protein stability independently of Mdm2, increased DNA binding and transcriptional activity, and showed efficacy in murine GI cancer and melanoma models (for review see [168]); (b) SCH529074, which reactivated and stabilized mutant p53 via Mdm2-dependent and independent mechanisms [169]; (c) ellipticine, which enhanced the transactivational activity of mutant p53, in particular transcription of Bax, p21, and Mdm2 (fro review see [151]); (d) RETRA (reactivation of transcriptional reporter activity), which induced tumor regression in xenogeneic explants harboring a R273H p53 mutation, presumably by release p73 from an inhibitory p73:p53 mutant complex [170]; (e) the aminothiol WR1065, the active metabolite of amifostine, which specifically reactivated the temperature-sensitive M272 p53 mutant, resulting in enhanced transcriptional induction of p21, GADD45 and MDM2, G1 cell cycle arrest [171]; and (f) p53R3, which restored DNA binding of p53 R175H and R273H mutants, robustly induced DR5 transcripts, and consequently exhibited synergistic pro-apoptotic effects in combination with TRAIL [172].

5. Expert opinion: When complex becomes too complex – the potential and perils of p53 targeting therapies

30 – 50,000 – 15 – these are the key figures that summarize our progress in driving p53-related basic science discoveries into clinical application: 30 years of research resulted in more than 50,0000 publications, and enabled enrollment of 15 p53-trageting agents into clinical studies. Can we harness the powerful tumor suppressive function of p53 for the treatment of cancer, or will the sheer endless complexities of p53 biology and the many, often diametrically opposed activities of p53 pose too many obstacles for drug development? These are some of the critical challenges:

5.1 Defining combinatorial complexity

The multitude of cellular stresses, the existence of different p53 family members, i.e. p53, p63, and p73, the various combinations of splice forms, the tissue-specific expression of these proteins, and their inhibitors (e.g., Mdm2 and Mdm4), together with the complex posttranslational modifications of individual isoforms create a highly convoluted signaling network (for detailed review on p53 family members p63 and p73, see [173]; for review of p53 isoforms, see [174]). Future research aims to understand, which inputs activate which functions of p53, and how the concerted action of p53 family proteins activates a specific, p53-driven transcriptional or cytoplasmic program. When does p53 induce cell survival, and what are the conditions, under which p53 triggers death and senescence?

The molecular understanding of these networks and the ability to predict p53-driven phenotypic endpoints, have grave implications for translating p53-targeting drugs into the clinic. First, p53 may help, rather than hinder neoplastic transformation, as this multifunctional transcription factor plays important roles in normal growth and development. Specifically, p53 impacts cellular metabolism, and promotes cell survival, e.g., by activating oxidative phosphorylation and limiting detrimental effects of ROS. Therefore, it will be important to molecularly understand and subsequently neutralize some of these pro-survival functions. Second, the p53 family relative p63 and p73 can functionally replace p53. Contrasting studies in CLL, Mdm2 inhibitors, such as nutlin-3, can induce apoptosis in certain p53-deficient tumor cells [175], likely by activating p63 and p73 and initiating a p63/p73-driven, p53-independent apoptotic program, which includes transactivation of PUMA and NOXA and subsequent caspase activation [176–179]. Therefore, it will be important to understand, which p53-mutant tumors can activate p63 and p73 in response to Mdm2 inhibition, to predict susceptibility toward nutlins or MI compounds. These findings will most definitely broaden the applicability of nutlins as anti-cancer therapeutics. Third, nutlin- and MI-targeting of Mdm2 may not be sufficient to activate p53, as Mdm4 can also regulate the stability and activity of p53 [180]. Mdm4 lacks ubiquitin-ligase activity, but can regulate p53 activity via binding of its N-terminal transcription activation domain to inhibit its transactivational activity, and to prevent complex formation with p300, which results in reduced acetylation, i.e. activation of p53. Understanding the context of Mdm-2-p53 and Mdm4-p53 interactions, and the development of small molecules that also inhibit Mdm4 or cause dual inhibition of Mdm2 and Mdm4 [181,182], will be critical to optimize Mdm-targeting therapies for clinical use. Of note, high throughput screens identified SJ-172550 as a potent inhibitor of the p53:Mdm4 interaction [182], and the benzofuroxan XI-006 (NSC207895) as an inhibitor of Mdm4 transcription [183]. Finally, drugs that bind to p53 rather than Mdm proteins to abrogate p53 degradation might be useful. Candidates include RITA (reactivation of p53 and induction of tumor cell apoptosis), which showed anti-tumor effects in murine colon cancer models by inducing conformational changes in p53 thereby preventing interaction with Mdm proteins [184], and the tryptamine derivate JNJ-26854165, which blocked p53 proteasomal degradation, inhibited tumor formation in lung, breast colon, and glioma xenograft models [185–187], and is currently enrolled in phase I clinical trials for the treatment of advanced solid tumors.

5.2 Defining the’ p53 pathway genotype’ as a prognostic marker

The type of inherited mutations in the p53 pathway, including p53 missense mutations, or deletions, inactivation of p14Arf, hyperactivation of Mdm2, Mdm4, WIP-1 by amplification or point mutations, or deregulated microRNA expression targeting p53 pathway components, have prognostic value. Consequently, oncogenomic surveys of modes to inactivate p53 will aid in stratifying patients according to their mutation profile, as certain drugs specifically inhibit the activity of p53 wildtype protein, while others act preferentially on cells with certain p53 missense mutations. A recent study employed high-density single nucleotide polymorphism arrays to analyze copy number alterations and p53 allele status in AML patients, and illustrated the importance of ex vivo genomic/transcriptomic profiling to predict tumor responses toward Mdm2 inhibition. Specifically, Saddler et al. demonstrated that p53 status in conjunction with additional molecular parameters, including mutations in the fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3), an important AML oncogene associated with poor clinical outcome, determine drug susceptibility [175].

5.3 Refining the drug development process

Small-molecule inhibitors have been developed for a broad spectrum of therapeutic applications. They block protein-protein-interaction that compromise cellular homeostasis; nutlins and MI compounds are important examples targeting the p53-Mdm2/4 interaction. Peptide-based therapies represent a valid alternative, as they mimic protein-protein actions more accurately than small molecules. Their translation into the clinic, however, has been hampered by conformational variability, and limited bioavailability. ‘Hydrocarbon peptide stapling’ is a recently developed methodology that uses hydrophobic linkers to ‘lock’ a peptide in a predetermined conformation. These stapled peptides are protease-resistant, cell-permeable, metabolically stable, bind multidomain proteins with high affinity [188], and were able to inhibit the p53-Mdm2 interaction [189].

5.4 Looking beyond canonical p53 signaling

‘Life was like a box of chocolates. You never know what you're gonna get’. This quote from the movie “Forrest Gump” also holds true for p53 research. p53 was discovered in 1979, initially characterized as an obscure oncogene, and finally established as a potent tumor suppressor with clinical applicability. At this critical juncture, p53 therapies are beginning to emerge in clinical practice and have the potential to make an impact on patients diagnosed with cancer. At the same time, the molecular elucidation of pathways impacted by p53 continues to surprise us by establishing unexpected connections between p53 signaling and diverse biological processes, e.g. metabolism, longevity, fertility, germ-line fidelity, stem cell reprogramming, autophagy, necrosis, angiogenesis, and tumor cell invasion. The next years will confirm these activities and possibly, incorporate them into translational approaches to optimize existing, and develop novel p53-based therapeutics. You never know what you’re gonna get.

Article Highlights.

p53 is a multi-faceted tetrameric transcription factor that transactivates a broad spectrum of genes implicated in cell cycle progression, cell death signaling, metabolism, DNA repair, and angiogenesis.

Depending on intensity and duration of cellular stresses, p53 has pro-survival and pro-death functions.

Several p53-targeting therapeutics have been developed, including adenoviral p53 vectors, dendritic cell-derived vaccines, small-molecules to reinstate the DNA binding activity of p53, inhibitors of Mdm2, a p53-degrading E3 ubiquitin ligase.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interest

The author has previously received funding from the Kimmel Scholar award, The Zell Family Foundation, Hoffman Research Fellowships and NIH funding, grant number: 4R00CA129172-03.

Bibliography

- 1. Vousden KH, Lane DP. p53 in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:275–283. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. * excellent review of the multi-faceted activity profile of p53.

- 2.Lane DP, Crawford LV. T antigen is bound to a host protein in SV40-transformed cells. Nature. 1979;278:261–263. doi: 10.1038/278261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarnow P, Ho YS, Williams J, et al. Adenovirus E1b-58kd tumor antigen and SV40 large tumor antigen are physically associated with the same 54 kd cellular protein in transformed cells. Cell. 1982;28:387–394. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werness BA, Levine AJ, Howley PM. Association of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 E6 proteins with p53. Science. 1990;248:76–79. doi: 10.1126/science.2157286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheffner M, Werness BA, Huibregtse JM, et al. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell. 1990;63:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robles AI, Harris CC. Clinical outcomes and correlates of TP53 mutations and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001016. a001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, et al. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990;250:1233–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.1978757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. * characterization of p53-deficient mice revealing potent tumor suppressive activity of p53.

- 10.Beckerman R, Prives C. Transcriptional regulation by p53. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000935. a000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. * excellent review on novel p53 functions.

- 12.Yonish-Rouach E, Resnitzky D, Lotem J, et al. Wild-type p53 induces apoptosis of myeloid leukaemic cells that is inhibited by interleukin-6. Nature. 1991;352:345–347. doi: 10.1038/352345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke AR, Purdie CA, Harrison DJ, et al. Thymocyte apoptosis induced by p53-dependent and independent pathways. Nature. 1993;362:849–852. doi: 10.1038/362849a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe SW, Ruley HE, Jacks T, et al. p53-dependent apoptosis modulates the cytotoxicity of anticancer agents. Cell. 1993;74:957–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe SW, Schmitt EM, Smith SW, et al. p53 is required for radiation-induced apoptosis in mouse thymocytes. Nature. 1993;362:847–849. doi: 10.1038/362847a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Yue P, Khuri FR, et al. p53 upregulates death receptor 4 expression through an intronic p53 binding site. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5078–5083. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller M, Wilder S, Bannasch D, et al. p53 activates the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) gene in response to DNA damage by anticancer drugs. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2033–2045. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikh MS, Burns TF, Huang Y, et al. p53-dependent and -independent regulation of the death receptor KILLER/DR5 gene expression in response to genotoxic stress and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1593–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peter ME, Krammer PH. The CD95(APO-1/Fas) DISC and beyond. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:26–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehrhardt H, Hacker S, Wittmann S, et al. Cytotoxic drug-induced, p53-mediated upregulation of caspase-8 in tumor cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:783–793. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attardi LD, Reczek EE, Cosmas C, et al. PERP, an apoptosis-associated target of p53, is a novel member of the PMP-22/gas3 family. Genes Dev. 2000;14:704–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies L, Gray D, Spiller D, et al. P53 apoptosis mediator PERP: localization, function and caspase activation in uveal melanoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1995–2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stegh AH, Peter ME. Apoptosis and caspases. Cardiol Clin. 2001;19:13–29. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyashita T, Reed JC. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human bax gene. Cell. 1995;80:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, et al. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;7:683–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oda E, Ohki R, Murasawa H, et al. Noxa, a BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family and candidate mediator of p53-induced apoptosis. Science. 2000;288:1053–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han J, Flemington C, Houghton AB, et al. Expression of bbc3, a pro-apoptotic BH3-only gene, is regulated by diverse cell death and survival signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11318–11323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201208798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soengas MS, Alarcon RM, Yoshida H, et al. Apaf-1 and caspase-9 in p53-dependent apoptosis and tumor inhibition. Science. 1999;284:156–159. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffers JR, Parganas E, Lee Y, et al. Puma is an essential mediator of p53-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Villunger A, Michalak EM, Coultas L, et al. p53- and drug-induced apoptotic responses mediated by BH3-only proteins puma and noxa. Science. 2003;302:1036–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1090072. * identification of PUMA and NOXA as critical regulators of p53-mediated apoptosis.

- 33.Chipuk JE, Maurer U, Green DR, et al. Pharmacologic activation of p53 elicits Bax-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcription. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caelles C, Helmberg A, Karin M. p53-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcriptional activation of p53-target genes. Nature. 1994;370:220–223. doi: 10.1038/370220a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson TM, Meade K, Pathak N, et al. Knockin mice expressing a chimeric p53 protein reveal mechanistic differences in how p53 triggers apoptosis and senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1215–1220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706764105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Kuwana T, et al. PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science. 2005;309:1732–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.1114297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, et al. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. * papers 36–37: Molecular dissection of cytoplasmic activities of p53.

- 38. Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, et al. p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2003;11:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. * first evidence of a molecular interplay between p53 and Bcl-2 family proteins at the level of mitochondrial membranes.

- 39.Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, et al. Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:443–450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stegh AH, Chin L, Louis DN, et al. What drives intense apoptosis resistance and propensity for necrosis in glioblastoma? A role for Bcl2L12 as a multifunctional cell death regulator. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2833–2839. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stegh AH, Kesari S, Mahoney JE, et al. Bcl2L12-mediated inhibition of effector caspase-3 and caspase-7 via distinct mechanisms in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10703–10708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712034105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stegh AH, Kim H, Bachoo RM, et al. Bcl2L12 inhibits post-mitochondrial apoptosis signaling in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2007;21:98–111. doi: 10.1101/gad.1480007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stegh AH, Brennan C, Mahoney JA, et al. Glioma oncoprotein Bcl2L12 inhibits the p53 tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2194–2204. doi: 10.1101/gad.1924710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stegh AH, Depinho RA. Beyond effector caspase inhibition: Bcl2L12 neutralizes p53 signaling in glioblastoma. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:33–38. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.1.14365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar S. Caspase 2 in apoptosis, the DNA damage response and tumour suppression: enigma no more? Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nrc2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tinel A, Tschopp J. The PIDDosome, a protein complex implicated in activation of caspase-2 in response to genotoxic stress. Science. 2004;304:843–846. doi: 10.1126/science.1095432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin Y, Ma W, Benchimol S. Pidd, a new death-domain-containing protein, is induced by p53 and promotes apoptosis. Nat Genet. 2000;26:122–127. doi: 10.1038/79102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zong WX, Thompson CB. Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1–15. doi: 10.1101/gad.1376506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan J, Kroemer G. Alternative cell death mechanisms in development and beyond. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2592–2602. doi: 10.1101/gad.1984410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tu HC, Ren D, Wang GX, et al. The p53-cathepsin axis cooperates with ROS to activate programmed necrotic death upon DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1093–1098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808173106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giono LE, Manfredi JJ. The p53 tumor suppressor participates in multiple cell cycle checkpoints. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:13–20. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sherr CJ. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.el-Deiry WS, Harper JW, O'Connor PM, et al. WAF1/CIP1 is induced in p53-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1169–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, et al. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brugarolas J, Chandrasekaran C, Gordon JI, et al. Radiation-induced cell cycle arrest compromised by p21 deficiency. Nature. 1995;377:552–557. doi: 10.1038/377552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, et al. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waldman T, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. p21 is necessary for the p53-mediated G1 arrest in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5187–5190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rohaly G, Chemnitz J, Dehde S, et al. A novel human p53 isoform is an essential element of the ATR-intra-S phase checkpoint. Cell. 2005;122:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.St Clair S, Giono L, Varmeh-Ziaie S, et al. DNA damage-induced downregulation of Cdc25C is mediated by p53 via two independent mechanisms: one involves direct binding to the cdc25C promoter. Mol Cell. 2004;16:725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Polyak K, et al. 14-3-3 sigma is a p53-regulated inhibitor of G2/M progression. Mol Cell. 1997;1:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ando T, Kawabe T, Ohara H, et al. Involvement of the interaction between p21 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen for the maintenance of G2/M arrest after DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42971–42977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Charrier-Savournin FB, Chateau MT, Gire V, et al. p21-Mediated nuclear retention of cyclin B1-Cdk1 in response to genotoxic stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3965–3976. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smits VA, Klompmaker R, Vallenius T, et al. p21 inhibits Thr161 phosphorylation of Cdc2 to enforce the G2 DNA damage checkpoint. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30638–30643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005437200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhan Q, Antinore MJ, Wang XW, et al. Association with Cdc2 and inhibition of Cdc2/Cyclin B1 kinase activity by the p53-regulated protein Gadd45. Oncogene. 1999;18:2892–2900. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jin S, Antinore MJ, Lung FD, et al. The GADD45 inhibition of Cdc2 kinase correlates with GADD45-mediated growth suppression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16602–16608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nezi L, Musacchio A. Sister chromatid tension and the spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cross SM, Sanchez CA, Morgan CA, et al. A p53-dependent mouse spindle checkpoint. Science. 1995;267:1353–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.7871434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Di Leonardo A, Khan SH, Linke SP, et al. DNA rereplication in the presence of mitotic spindle inhibitors in human and mouse fibroblasts lacking either p53 or pRb function. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1013–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fukasawa K, Choi T, Kuriyama R, et al. Abnormal centrosome amplification in the absence of p53. Science. 1996;271:1744–1747. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lanni JS, Jacks T. Characterization of the p53-dependent postmitotic checkpoint following spindle disruption. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1055–1064. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith ML, Chen IT, Zhan Q, et al. Interaction of the p53-regulated protein Gadd45 with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Science. 1994;266:1376–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.7973727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith ML, Kontny HU, Zhan Q, et al. Antisense GADD45 expression results in decreased DNA repair and sensitizes cells to u.v.-irradiation or cisplatin. Oncogene. 1996;13:2255–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Janus F, Albrechtsen N, Dornreiter I, et al. The dual role model for p53 in maintaining genomic integrity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:12–27. doi: 10.1007/s000180050266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. p53 regulation of metabolic pathways. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001040. a001040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ma W, Sung HJ, Park JY, et al. A pivotal role for p53: balancing aerobic respiration and glycolysis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2007;39:243–246. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kulawiec M, Ayyasamy V, Singh KK. p53 regulates mtDNA copy number and mitocheckpoint pathway. J Carcinog. 2009;8:8. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.50893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lebedeva MA, Eaton JS, Shadel GS. Loss of p53 causes mitochondrial DNA depletion and altered mitochondrial reactive oxygen species homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Matoba S, Kang JG, Patino WD, et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Okamura S, Ng CC, Koyama K, et al. Identification of seven genes regulated by wild-type p53 in a colon cancer cell line carrying a well-controlled wild-type p53 expression system. Oncol Res. 1999;11:281–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schwartzenberg-Bar-Yoseph F, Armoni M, Karnieli E. The tumor suppressor p53 down-regulates glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4 gene expression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2627–2633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawauchi K, Araki K, Tobiume K, et al. p53 regulates glucose metabolism through an IKK-NF-kappaB pathway and inhibits cell transformation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:611–618. doi: 10.1038/ncb1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kondoh H, Lleonart ME, Gil J, et al. Glycolytic enzymes can modulate cellular life span. Cancer Res. 2005;65:177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bensaad K, Vousden KH. p53: new roles in metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li H, Jogl G. Structural and biochemical studies of TIGAR (TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1748–1754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807821200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vousden KH. Functions of p53 in metabolism and invasion. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:511–517. doi: 10.1042/BST0370511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Muniyappa H, Song S, Mathews CK, et al. Reactive oxygen species-independent oxidation of thioredoxin in hypoxia: inactivation of ribonucleotide reductase and redox-mediated checkpoint control. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17069–17081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Budanov AV, Sablina AA, Feinstein E, et al. Regeneration of peroxiredoxins by p53-regulated sestrins, homologs of bacterial AhpD. Science. 2004;304:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1095569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cano CE, Gommeaux J, Pietri S, et al. Tumor protein 53-induced nuclear protein 1 is a major mediator of p53 antioxidant function. Cancer Res. 2009;69:219–226. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen W, Sun Z, Wang XJ, et al. Direct interaction between Nrf2 and p21(Cip1/WAF1) upregulates the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response. Mol Cell. 2009;34:663–673. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hayflick L. The Limited in Vitro Lifetime of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zilfou JT, Lowe SW. Tumor suppressive functions of p53. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001883. a001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brown JP, Wei W, Sedivy JM. Bypass of senescence after disruption of p21CIP1/WAF1 gene in normal diploid human fibroblasts. Science. 1997;277:831–834. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, et al. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell. 2003;113:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Narita M, Krizhanovsky V, Nunez S, et al. A novel role for high-mobility group a proteins in cellular senescence and heterochromatin formation. Cell. 2006;126:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, et al. p53 activates ICAM-1 (CD54) expression in an NF-kappaB-independent manner. EMBO J. 2003;22:1567–1578. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. ** in vivo evidence that restoration of p53 halts progression of liver cancer.

- 97.Campisi J. Cancer and ageing: rival demons? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:339–349. doi: 10.1038/nrc1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vijg J, Suh Y. Genetics of longevity and aging. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:193–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal homeostasis: a balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:207–217. doi: 10.1038/nrm2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008;132:631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schoppy DW, Ruzankina Y, Brown EJ. Removing all obstacles: a critical role for p53 in promoting tissue renewal. Cell Cycle. 9:1313–1319. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.7.11194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, et al. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature. 2002;415:45–53. doi: 10.1038/415045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dumble M, Moore L, Chambers SM, et al. The impact of altered p53 dosage on hematopoietic stem cell dynamics during aging. Blood. 2007;109:1736–1742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-010413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Matheu A, Maraver A, Klatt P, et al. Delayed ageing through damage protection by the Arf/p53 pathway. Nature. 2007;448:375–379. doi: 10.1038/nature05949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Garcia-Cao I, Garcia-Cao M, Tomas-Loba A, et al. Increased p53 activity does not accelerate telomere-driven ageing. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:546–552. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, et al. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Martins CP, Brown-Swigart L, Evan GI. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell. 2006;127:1323–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.007. ** in vivo evidence that restoration of p53 halts cancer progression.

- 108.Junttila MR, Karnezis AN, Garcia D, et al. Selective activation of p53-mediated tumour suppression in high-grade tumours. Nature. 468:567–571. doi: 10.1038/nature09526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Feldser DM, Kostova KK, Winslow MM, et al. Stage-specific sensitivity to p53 restoration during lung cancer progression. Nature. 468:572–575. doi: 10.1038/nature09535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]