Summary

Background

A key feature of factor IXa (fIXa) is its allosteric transformation from an enzymatically latent form into a potent procoagulant. Whilst several small molecules have been found capable of partially effecting fIXa function (i.e. ethylene glycol, calcium ion and LMWH), the resulting modest changes in peptidolytic activity have made the study of their mechanisms of action challenging. Since these effects yield hints into potential regulatory forces that may be operational in full expression of fIXa coagulant activity, their description remains of high interest. Studies of crystal structures have yielded insight into structural changes induced by these effectors, but there remains a paucity of information to correlate any given structural change with specific consequences on fIXa function.

Objectives

To correlate structural changes induced by these modulators with defined consequences in fIXa substrate discrimination and function.

Methods

A peptidomics-based MS approach was used to examine patterns of hydrolysis of four combinatorial chemistry-derived pentapeptide libraries by fIXa under various conditions in a soluble, active enzyme system.

Results

Ethylene glycol specifically alters the S3 subsite of fIXa to render it more tolerant to side chains at the P3 substrate position, while calcium enhances tolerance at the S2 subsite. In contrast, LMWH alters both S2 and S1' subsites.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate the role of plasticity in regulating fIXa function with respect to discrimination of extended substrate sequences, as well as provide crucial insight into active site modulations that may be capitalized upon by various physiological cofactors of fIXa and in future drug design.

Keywords: factor IXa, hemophilia, thrombosis, enzymology, structure, substrate

Introduction

Blood coagulation factor IXa (fIXa)1 is a member of the serine protease family of enzymes and a crucial part of the intrinsic pathway of blood coagulation [1, 2]. Its deficiency, or that of its major protein cofactor factor VIII, results in hemophilia B and A, respectively. Conversely, excessive fIXa activity has been implicated in thrombotic disease [3]. Maximal procoagulant activity of fIXa is observed only when in the context of a quaternary complex with three essential cofactors; activated factor VIII (factor VIIIa), ionic calcium (Ca2+), and an anionic phospholipid membrane surface. The resulting lipid-bound enzyme-cofactor complex (commonly referred to as the intrinsic “tenase” complex) exhibits an overall 109-fold enhancement in activity towards its native substrate, factor X. The numerous structural mechanisms and molecular details that define this dramatic enhancement in procoagulant activity are not well defined and remain the subject of much investigation.

An interesting feature of fIXa that separates it from other blood coagulation proteases is its comparatively low peptidolytic activity even in the context of the fully-assembled tenase complex, which exhibits full procoagulant (proteolytic) activity. The combination of these seemingly contradictory enzymological characteristics strongly supports the notion of a poorly-formed (but functional) fIXa catalytic center (as revealed in available crystal structures [4, 5]) whose deficiencies are corrected for or overcome by cofactor-induced molecular effects outside of the catalytic center. In this view, these cofactor-induced changes result in the elaboration of sufficient proteolytic activity towards the macromolecular substrate factor X to support coagulation, with little (though in some cases measurable) elaboration of activity towards small substrates (such as peptides). Though intriguing, these characteristics have severely hampered studies of fIXa enzymatic activity and its mechanisms using traditional enzymological techniques. While numerous studies have been published concerning the esterolytic and amidolytic activities of thrombin, factor Xa and factor VIIa, there is a comparative paucity of such studies with fIXa. Instead, these characteristics have led to the majority of enzymological studies of fIXa focusing on the elucidation of macromolecular effects of cofactor binding. This has produced a complex (though still incomplete) model of enzymatic enhancement that involves a fascinating array of inter-connected macromolecular mechanisms (reviewed in [6, 7]).

Ethylene glycol has previously been determined to enhance the activity of fIXa as well as other clotting serine proteases, though not all [8–10], through an unknown mechanism. While the action of ethylene glycol per se does not have physiological significance in fIXa clotting activity, its ability to affect fIXa activity is intrinsically of great interest owing to the difficulties that have been observed in gaining insight into the function and regulation of this cryptic serine protease. Thus, understanding the molecular details of this effect, as well as that of other modulators, and correlating them to precise functional consequences is a highly significant prerequisite to allow their future exploitations in drug design. This information will help to garner a deeper understanding and appreciation for the role of enzyme plasticity and subtle structural modulations in defining proteolytic activity and regulation.

Given the subtle nature of the proposed modulations in describing the dramatic increase in fIXa enzyme activity [11–13], it remains critical to accurately compare and correlate observed structural perturbations with actual effects on enzyme function in the context of the native and physiologically-relevant enzyme. This remains a daunting task. The goal of the present study was to gain further insight into such correlations by examining specific functional consequences of perturbations that occur in the fIXa active site upon stimulation with various known, and relatively simple, effectors; calcium-ion [14], low molecular weight heparin [13, 15], and ethylene glycol [9, 10, 13]. The approach involved the merging of combinatorial chemistry and peptidomics to probe the fIXa active site for alterations induced by these various modulators in an active, soluble enzyme system using native fIXa. While the results generally confirm the alteration of specific enzyme subsites as observed in static crystal structures, there are some critical differences observed that may have implications in future drug design as well as our understanding of fIXa modulatory effects and conformational activation events.

Methods

Reagents

Ammonium bicarbonate, calcium chloride, and ethylene glycol were from Fisher Scientific (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). The low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) Lovenox was from Sanofi-Aventis (Bridgewater, NJ, U.S.A.). Trypsin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Bovine serum albumin (BSA; fraction V - fatty acid free) was from CalBiochem (La Jolla, CA). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) were from Fluka Analytical (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Buchs, Switzerland). Native, human factor IXaβ (fIXa) was obtained from Haematologic Technologies, Inc (Essex Junction, VT, U.S.A.). Spectrozyme FIXa, Spectrozyme t-PA and Spectrozyme FXIIa substrates were from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT). CBS 31.39 and CBS 48.03 substrates were from Diagnostica Stago (Parsippany, NJ).

Peptide Libraries

The four pentapeptide libraries used were derived from the extended reactive sequence of human antithrombin, AGRSL [13]. This peptide is referred to as the base peptide (AT3.2). Each library contained a pool of 20 peptides containing one degenerate position where each of the 20 amino acids had been incorporated (refer to text and Table 1) using combinatorial chemistry and l-isomers throughout. The Arg at the P1 position was left unchanged to allow hydrolysis by trypsin-like serine proteases. To better mimic a continuous peptide chain and reduce potential artificial effects of charged termini, all peptides were synthesized with N-terminal acetyl (Ac) and C-terminal amide (Am) blocking groups (Ac-AGRSL-Am).

Table 1.

Peptide Libraries Based on AT3.2 Pentapeptide

| Amino Acid Identity and Position* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (P3) | (P2) | (P1)↓ | (P1') | (P2') | |

| AT3.2 Base Peptide: | A | G | R | S | L |

| P3 Library | X | G | R | S | L |

| P2 Library | A | X | R | S | L |

| P1' Library | A | G | R | X | L |

| P2' Library | A | G | R | S | X |

Each library was synthesized using combinatorial chemistry with l-isomers of amino acids and blocked with an acetyl (Ac) moiety on the N-terminus and an amide (Am) moiety on the C-terminus. Each peptide library contains all 20 possible amino acids substituted at the position denoted by an X. The P1 Arg was not varied to allow for peptide hydrolysis (arrow) by fIXa (a trypsin-like serine protease).

All peptides and peptide libraries were synthesized by New England Peptides, Inc (Gardner, MA, U.S.A.) using Fmoc chemistry and were HPLC purified. Their spectral masses were determined to be within 0.1% of the exact expected molecular weights as provided. Typical reactions used 1 mM of the entire peptide library, or ~50 µM of each peptide sequence.

Peptide Library Hydrolysis Reactions

Unless indicated otherwise, enzyme reactions were done using either 10 nM trypsin or 25 nM fIXa in 100 mM NH4HCO3, pH 8 at 37°C for either 1 hour (trypsin) or 18 h (fIXa) with indicated additives. Reactions were terminated upon drying to completion in a Speed-Vac (Savant) and then frozen at −20°C until MS analysis.

Chromogenic Enzyme Assays

Assays were done in 96-well microplates (untreated polystyrene; Corning, NY) at ambient temperature essentially as previously described [13, 15]. Standard final reaction conditions were 25 nM fIXa in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) BSA, and 5 mM CaCl2 unless indicated otherwise.

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectral analyses of peptide libraries [16] were performed using a Kratos Axima-CFR Kompact MALDI-TOF MS instrument (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Calibration of the instrument was done using a 1:1 mixture of undigested and trypsin-digested AT3.2 peptide (1 mM). Immediately prior to MS analysis, reaction samples were reconstituted in 10 µl of 0.1% TFA. 1 µl of each sample was then mixed directly on a stainless steel sample plate with an equal volume of DHB matrix [17] (10 mg/mL in 60% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA) and allowed to crystallize at room temperature. MS spectra were recorded in the positive reflectron mode with the pulsed extraction mass set to the center of the range of masses being investigated. Under these conditions, hydrolysis products were identifiable at levels as low as 5 ng. To facilitate proper identification of products a spotting level of 25 ng was used throughout.

Data Analysis

Kratos Analytical Ltd software (Kompact, v 2.4.1) was used to visualize MALDI spectra and identify substrate and product peaks as well as to perform spectral smoothing by averaging and to calculate peak areas. Results were internally normalized for each identified peptide sequence by taking into consideration the remaining unhydrolyzed (intact) peptide mass peak and the mass peak of the unique hydrolysis product resulting from normal hydrolysis C-terminal to the P1 Arg. This is defined by Equation 1:

| (Eq. 1) |

Each library and condition was tested in triplicate and hydrolysis percentages are reported as averages. This internal normalization procedure takes into account and corrects for all variations in individual peptide levels, reaction mixtures, sampling/pipetting as well as laser-shot variations. In order to compare values across peptide libraries, values of % Hydrolysis were secondarily normalized to the hydrolytic activity observed towards the base peptide sequence AGRSL, which was present in each library (internal control). This step takes into account and corrects for any variation in fIXa activity between experiments and is reported as Fractional Reactivity (Equation 2).

| (Eq. 2) |

Results

Previous studies by us demonstrated that an Ac-AGRSL-Am pentapeptide substrate (AT3.2) could sense changes in fIXa enzymatic activity as induced by calcium, heparin and ethylene glycol [13]. To further elucidate the basis for the effects of these modulators on the active site of fIXa, we used the AT3.2 peptide as a base peptide sequence to generate four individual peptide libraries (Table 1) by combinatorial chemistry (New England Peptides, Inc.). Each library represented a pool of 20 different pentapeptide sequences with a single degenerate amino acid in the sequence at either the P3, P2, P1' or P2'. The P1 position was left unchanged (Arg) in all libraries to allow for hydrolysis by serine-like proteases. Since the base peptide sequence AGRSL was present in all four libraries, 77 different peptide sequences were theoretically represented (see below).

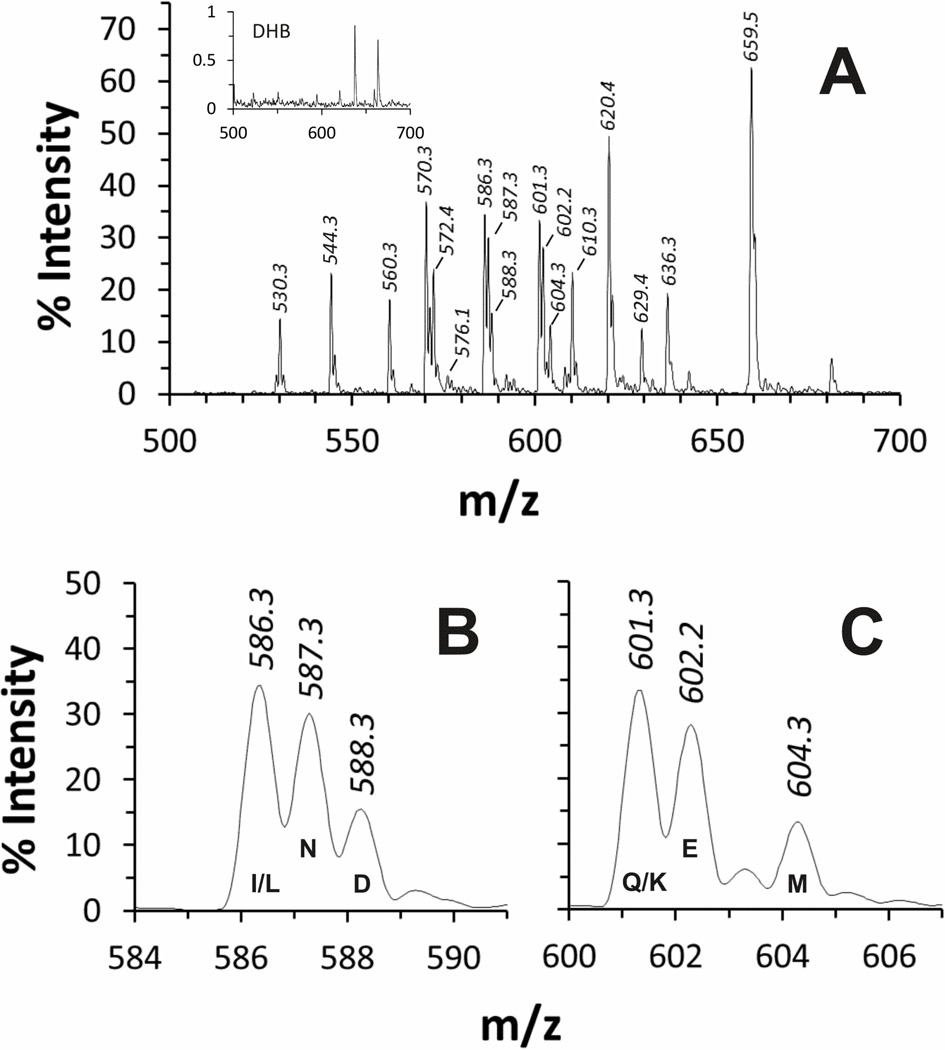

Characterization of the peptide sequences represented in each library

A sample of each library was mock-digested (no enzyme), dried, dissolved in 0.1% TFA and spotted on a MALDI target at 500 ng per spot (roughly 25 ng of each peptide). A typical MS spectrum (P3 library) is shown in Fig 1A. Although substantial variations were observed in peak height and area for the different peptides present in each library, the differences were reproducible and consistent between experiments. Thus, it is likely that this reflects differences in peptide synthesis levels and laser desorption/ionization efficiency as opposed to experimental variability. Of all the expected peptides in each library, only the Thr version of each degenerate peptide was not identified to a significant extent (albeit Ac-AGRST-Am was identified at an extremely low level in the P2' library). In addition, since Ile and Leu have identical masses, and Gln and Lys have masses indistinguishable from each other at the resolution of this system, both of these peptide pairs yielded single peaks (Figs 1B and 1C). None of these peptide peaks were observed when the peptide was left out of the reaction mixture, and minimal background signal was observed from the matrix/buffer system (Fig 1A, inset).

Figure 1. MALDI-TOF analysis of the intact AT3.2-P3 peptide library.

A typical MS spectrum of the AT3.2-P3 library is shown for illustrative purposes (panel A). Values of % Intensity were normalized to that of the DHB matrix peak (m/z of 154, not shown). The MS spectrum in the absence of peptide (essentially the DHB matrix alone) revealed insignificant masses in the range examined (inset). Each peptide library revealed 17 peptide m/z peaks corresponding to 19 out of the 20 possible peptide sequences (as labeled; refer to supplemental data Tables s1–s4). Due to Ile and Leu having identical masses, as do Gln and Lys, peptides containing these residues at the degenerate position have masses indistinguishable from each other at the resolution of this system (panels B and C).

Hydrolysis of the libraries by fIXa

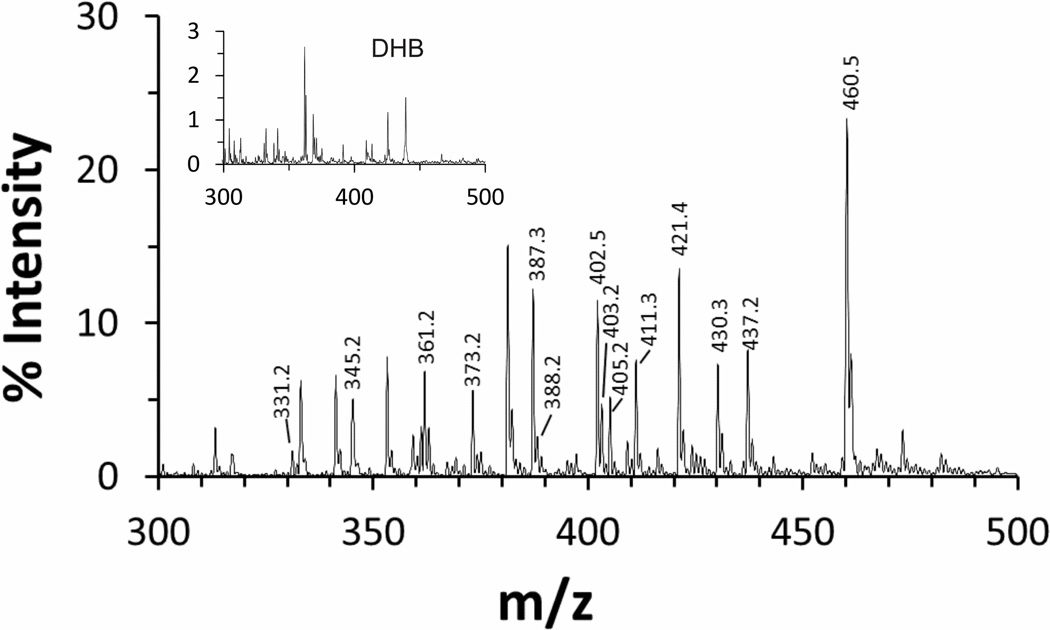

The peptide hydrolysis MS spectrum of each of the libraries was determined for fIXa alone, and in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+, 10 µM LMWH, 30% ethylene glycol, or combinations. MS analyses of each reaction produced well-resolved groups of substrate and product peaks (Fig 2 and supplemental Fig s1). As expected, the number and levels of products observed was different under each condition. Generally, the Arg version of each degenerate peptide was present only in low levels and produced sporadic results. Likewise, Cys-containing peptides, although observable, were present only at low levels and the libraries contained extremely variable levels of oxidized dimers that were not well hydrolyzed. Thus, results from sequences containing Thr, Cys, or Arg in the degenerate position were omitted from subsequent analysis. In addition, since the m/z of peptides containing either Ile/Leu or Gln/Lys in the degenerate position were indistinguishable from each other (cf. Fig 1 and supplemental Tables s1–s4), the areas for these peaks were considered as representative of the peptide pairs as opposed to the individual sequences. Thus, the final analysis focused on 15 m/z peaks (17 peptide sequences) for each library, or 65 total different peptide sequences out of the 77 theoretically possible. The representation of peptide sequences in each library was close to expected levels but did exhibit some variability (supplemental Fig s2), necessitating normalization procedures (Eqs 1 and 2).

Figure 2. MALDI-TOF analysis of the hydrolyzed AT3.2-P3 peptide library.

A typical MS spectrum of the AT3.2-P3 library after hydrolysis with fIXa in the presence of 30% ethylene glycol is shown for illustrative purposes. Values of % Intensity were normalized to that of the DHB matrix peak (m/z of 154, not shown). The MS spectrum for the reaction mixture in the absence of peptide (essentially the DHB matrix alone) revealed insignificant masses in the m/z range examined (inset). Each peptide library and condition examined revealed different product m/z peaks, but all products were readily identifiable based on their expected m/z values (refer to supplemental data Tables s1–s4). The analysis focused on 15 potential m/z product peaks representing 17 peptide sequences.

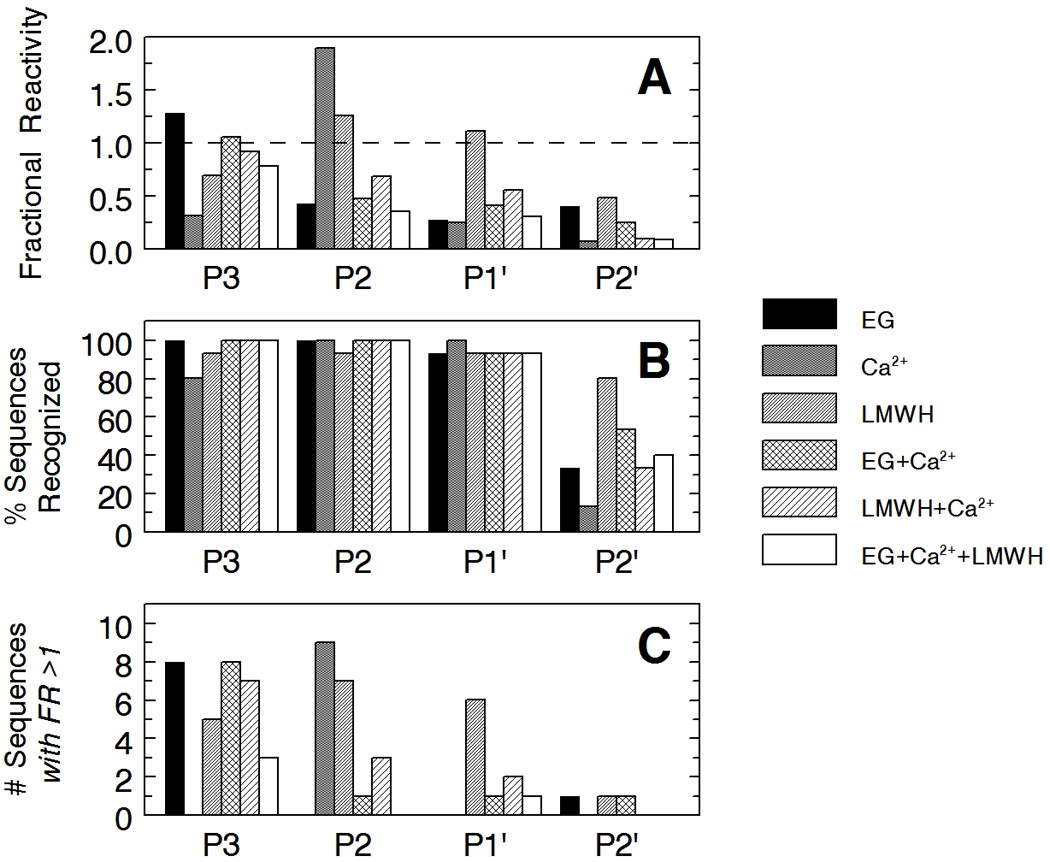

Correlations between fIXa subsite modulations and substrate discrimination

As expected due to its poor activity, fIXa alone showed extremely low and sporadic hydrolysis of all four libraries (not shown). However, the addition of any of the three effectors substantially increased and stabilized hydrolytic activity allowing consistent MS measurements to be made. For each library, an average value for Fractional Reactivity (reactivity normalized to AGRSL) was determined under each condition to allow inter-library comparisons to be made. The analyzed data is shown in Fig 3A as the overall Fractional Reactivity observed with each library at each condition examined. The results reveal complex responses to multiple effectors, but fairly clear responses to singular effectors. The predominant effect of ethylene glycol alone was observed with the P3 library, and the predominant effect of calcium alone was observed with the P2 library. LMWH was found to have the most global effect, but was predominantly observed with the P2 and P1' libraries. Despite these differences, the total number of peptides in each library that were hydrolyzed to any extent remained fairly constant, with most conditions yielding identifiable products for 80–100% of the different peptide sequences represented in the libraries (Fig 3B). The obvious exception to this was the P2' library for which the number of products observed was significantly lower. The pattern observed in Fig 3A was reproduced when plots of the number of peptides in each library whose Fractional Reactivity was greater than 1.0 were examined for each condition (Fig 3C). This analytical view supports the notion that for those conditions where average Fractional Reactivity increased, it was due to an overall increase in tolerance of variation and not just an increase in Fractional Reactivity of a few preferred sequences. Together, this data re-affirms the targeting of the beneficial effects of ethylene glycol, calcium, and LMWH to specific fIXa subsites as sensed by the various peptide degenerate amino-acid positions. In addition, this analysis demonstrates the effects of these modulations on enhancing global substrate side chain accommodation (substrate discrimination) of the fIXa subsites rather than in defining single-substrate specificity or recognition.

Figure 3. Modulation of substrate discrimination by fIXa.

Panel A—The average Fractional Reactivity of each of the four different peptide libraries (P3, P2, P1' and P2') for fIXa in the presence of various known fIXa effectors is shown. Effectors as indicated are: EG, 30% v/v ethylene glycol; Ca2+, 5 mM ionic calcium; LMWH, 10 µM low molecular weight heparin (Lovenox). Values for Fractional Reactivity were obtained from mean values of % Hydrolysis (n = 3) which were then normalized to the mean % Hydrolysis of the base AGRSL peptide present in each library (arbitrarily defined as 100% Hydrolysis and Fractional Reactivity of 1.0, dotted line) (refer to Eqs 1 & 2). Panel B—The percentage of sequences recognized under each condition examined is indicated for each library. The values are based on the 17 peptide sequences that were included in the analysis of each library; sequences containing Thr, Cys or Arg at the degenerate position were omitted (see Results pg 12). Most conditions examined produced at least detectable levels for the majority of sequences. The P2' library showed the fewest products, likely due to solubility issues with this library. Panel C—To gain further insight into overall enhancements in reactivity over the AGRSL base peptide sequence, the number of sequences (out of the 15 total product peaks examined) with a Fractional Reactivity greater than 1.0 (FR > 1.0) are shown. These results indicate that for the main modulations observed, the average values of Fractional Reactivity in Panel A are not simply due to very large increases in reactivity towards a few sequences, but rather are indicative of overall increases in reactivity towards the majority of sequences in the libraries.

Correlations between fIXa subsite modulations and rates of substrate hydrolysis

The above results demonstrate a specific functional consequence of each fIXa effector that is focused on a specific and different fIXa subsite. While these modulations clearly affect substrate discrimination, they may or may not also be involved in affecting subsequent enzymatic events in peptide hydrolysis. Since the observed effects of calcium and ethylene glycol were focused on specific subsites that are amino-terminal to the scissile bond (non-prime side), we were able to examine the potential kinetic consequences of these defined modulations using commercially-available chromogenic substrates. The use of these substrates, as opposed to the pentapeptide substrates used above, greatly facilitates subsequent kinetic analyses as well as provides valuable validation of the above observations by an alternative method. The chromogenic substrates used are given in Table 2 and were obtained from several suppliers. All are p-nitroanilide based substrates with small defined differences in P4, P3 and P2 positions, thus allowing direct comparisons to be made concerning the effects of the various modulators.

Table 2.

Sequences of chromogenic substrates examined with fIXa*

| Sequence |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | (P4) | (P3) | (P2) | (P1)↓ | (P1') |

| Spectrozyme FIXa | d-L | phG | R | p-nitroanilide | |

| CBS 31.39 | CH3SO2 | d-L | G | R | p-nitroanilide |

| CBS 48.03 | CH3OCO | d-L | G | R | p-nitroanilide |

| Spectrozyme t-PA | CH3SO2 | d-chT | G | R | p-nitroanilide |

| Spectrozyme FXIIa | d-chT | G | R | p-nitroanilide | |

Each tripeptidyl chromogenic substrate sequence is presented from N-terminus to C-terminus. The CH3SO2 and CH3OCO moieties on three of the substrates are amino-terminal blocking groups. All of the chromogenic substrates contained a d-isomeric amino acid at the P3 position, and three of the five incorporated modified amino acids; phG (phenylated Gly) or chT (cyclohexyl-Thr). Hydrolysis by trypsin-like serine proteases occurs at the amide bond between the P1 Arg residue and the P1' p-nitroanilide moiety (arrow).

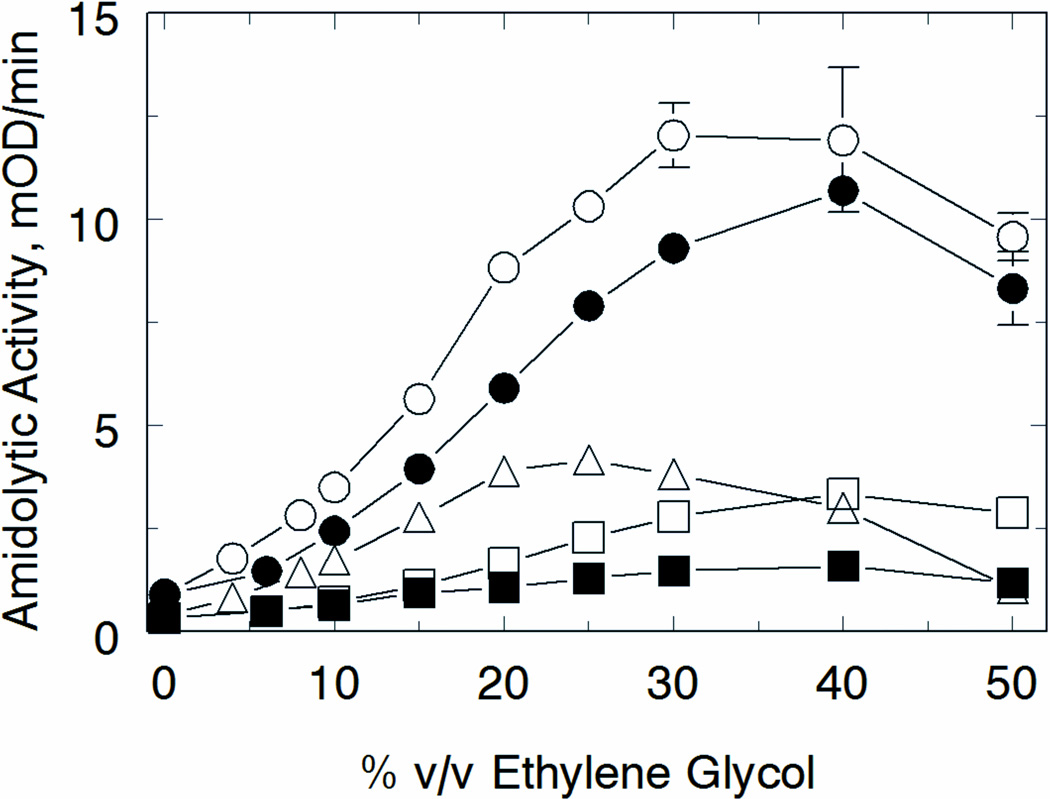

Heparin alone had little to no effect on altering the initial rates of hydrolysis of these substrates (not shown). In contrast, ethylene glycol enhanced the activity of fIXa towards all the substrates in a substrate-sequence dependent manner. For the four substrates with Gly at the P2 position, maximal fIXa activity was observed in the presence of 30–40% v/v ethylene glycol (Fig 4), consistent with previous observations [8, 10]. The sole substrate containing a bulky phenylated-Gly in the P2 position (Spectrozyme FIXa) exhibited substantially different ethylene glycol dependence, with peak activity observed at significantly lower levels of ethylene glycol (20–25% v/v). Of additional interest, only the two substrates containing CH3SO2 in the P4 position (as the blocking group) exhibited the maximal 17-fold enhancement in reactivity. The remaining substrates, with a different or no blocking group, exhibited only a 2- to 4-fold enhancement in reactivity. Considering that each of the chromogenic substrates use the d-isomer of Leu in the P3 position, the subsequent opposite steric positioning of the N-terminal blocking group in the active site makes this result fully consistent with effects of ethylene glycol on the S3 subsite as described above (see Discussion). Examination of the kinetic parameters of substrate hydrolysis indicated that this effect was likely due to a change in Km for substrate, with no measurable change in kcat (Fig s3).

Figure 4. Substrate sequence specificity of the ethylene glycol effect on fIXa chromogenic activity.

Initial rates of hydrolysis of CBS 31.39 (○), Spectrozyme t-PA (●), CBS 48.03 (□), Spectrozyme FXIIa (■), and Spectrozyme FIXa (△) were measured under standard conditions with increasing concentrations of ethylene glycol (% v/v). The sequence of each substrate is given in Table 2. Points are means of triplicate determinations ± standard error.

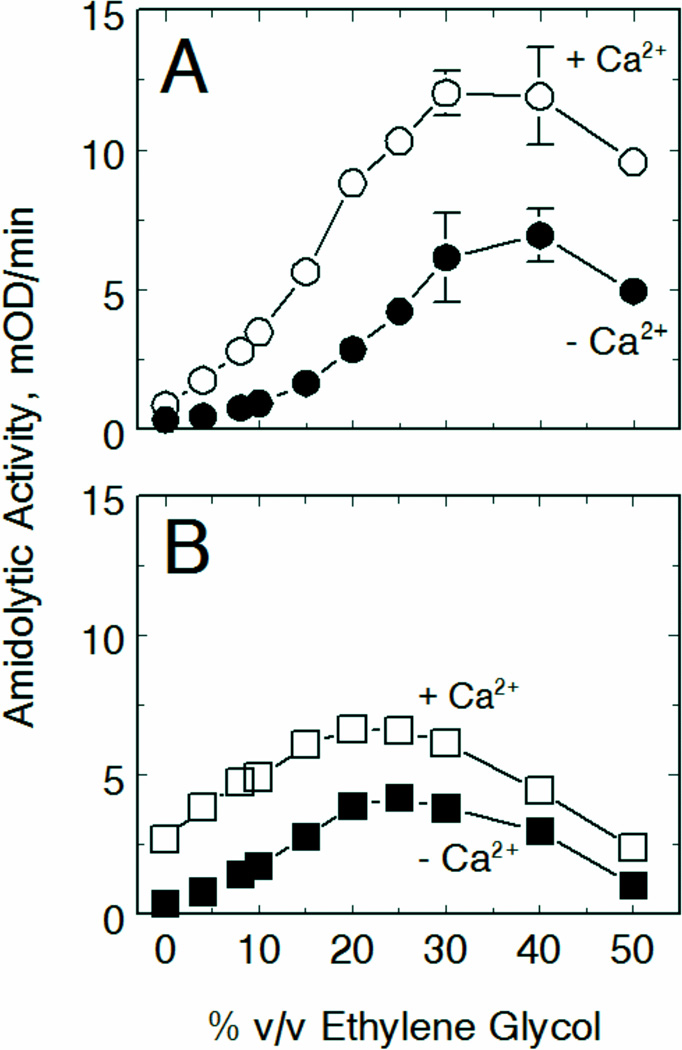

An examination of the calcium dependence of substrate hydrolysis revealed that while calcium effectively enhanced the ability of fIXa to hydrolyze all the substrates to some degree, hydrolysis of Spectrozyme FIXa was affected differently than that of the other substrates (Fig 5B). This was most apparent in the absence of ethylene glycol, where fIXa activity was greatest towards Spectrozyme FIXa compared to all the other substrates. This result is consistent with calcium binding enhancing the side-chain tolerance of the S2 subsite in fIXa as observed above (cf. Fig 3).

Figure 5. Substrate sequence specificity of the calcium effect on fIXa chromogenic activity.

Initial rates of hydrolysis of CBS 31.39 (panel A) or Spectrozyme FIXa (panel B) were measured using standard reaction conditions and the indicated levels of ethylene glycol in the presence of either 5 mM calcium ion (○,□) or 2.5 mM EDTA (●,■). Points are means of triplicate determinations ± standard error.

Discussion

This study addresses a crucial gap in the study and understanding of fIXa activity and regulation. By examining the changes in hydrolysis patterns of four pentapeptide libraries by fIXa in the presence of three different known small molecule effectors of fIXa (ethylene glycol, calcium and LMWH) we have been able to begin establishing correlations between the structural alterations induced by these relatively simple effectors [12, 15] and specific functional consequences with respect to substrate discrimination functions by fIXa.

Interpretation of the results and comparison across libraries required a secondary normalization procedure of the data to determine Fractional Reactivity compared to the base peptide sequence AGRSL (Equation 2). Thus, potential effects on the reactivity of the AGRSL peptide with fIXa under the various conditions are not observable. These normalization steps were required due to the variability observed in absolute % Hydrolysis values between MALDI experiments (although hydrolysis patterns remained constant) as well as the variation in the level of each peptide in the libraries. While this precludes conclusions to be drawn with respect to substrate sequence preferences within libraries or effects on initial rates of hydrolysis, this procedure does facilitate and allow the examination of changes in overall patterns of reactivity across libraries, which is the main premise of the study.

Modulation of the fIXa S3 region

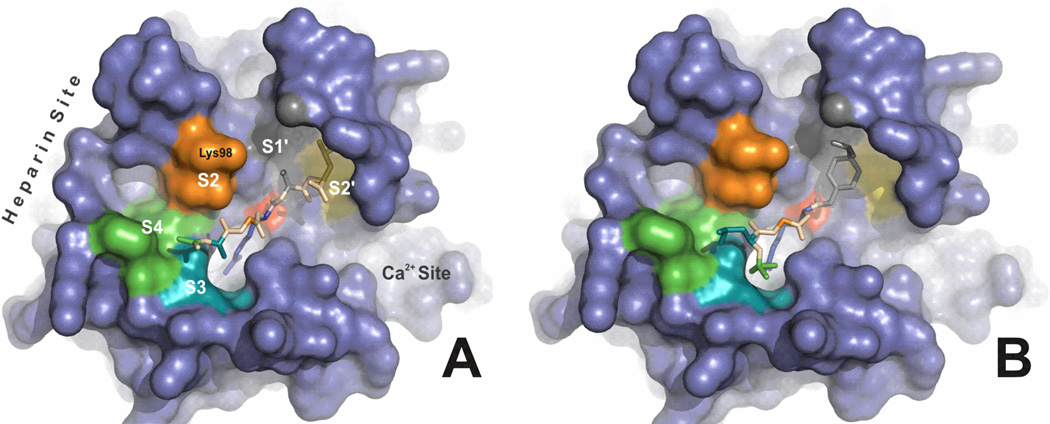

Our results demonstrate that the ethylene glycol-induced alterations in fIXa predicted by fluorescence studies [8] and observed in structural studies [12] can be correlated to enhanced tolerance of variation of l-amino-acid side chains at the P3 position of peptide substrates. This result provides direct evidence of a specific functional consequence of S3 modulation by ethylene glycol and supports a model of this effector producing a more side-chain accessible S3 region. We have previously reported that ethylene glycol induces specific changes in the fluorescence of Fl-d-FPR-labeled fIXa that are not observed with other similarly-labeled blood clotting serine proteases [8]. This suggested that the effect of ethylene glycol on fIXa was at least in part due to specific structural alterations of fIXa near the dye. Although the fluorescein dye of the inhibitor as well as the CH3SO2 moiety of the chromogenic substrates used here are located at the P4 position of the linear peptide sequence, based on the presence of a d-isomeric amino acid at the P3 position in both of these peptides, as well as on the intrinsic rotatability of the amide bond, it is quite feasible (and in fact highly probable) that the moiety at the P4 position of these non-natural peptides senses changes in the region of fIXa that is typically defined as S3. This is supported in molecular docking simulations (Fig 6) and is consistent with the proposed binding site of ethylene glycol adjacent to the S3 region in crystal structures of fIXa [12]. The docking configuration of the free AGRSL peptide is supported by the recent study from the Huntington lab describing the crystal structure of AT-bound fIXa in the presence of calcium and pentasaccharide [18].

Figure 6. Molecular docking models of fIXa and peptide substrates.

The AGRSL base peptide (panel A) or CBS 31.39 (panel B) was docked into the active site of fIXa (pdb code 1RFN) using AutoDock Vina [19] and displayed using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.4, Schrödinger, LLC. Putative subsites in fIXa are indicated (S4, S3, S2, S1' and S2') and are color-coded to match the corresponding amino acid position in the peptide. The P1 Arg residue is shown in blue inserted into the primary S1 specificity pocket of fIXa. The calcium-ion binding site and the LMWH (heparin) binding regions in fIXa are indicated. Lys98, which is part of the 99-loop and forms part of the S2 region, has been shown to be directly modulated by heparin binding [15]. The orientations of the P3 and P4 residues are reversed in CBS 31.39 (which incorporates a d-isomeric Leu in the P3 position) compared to the AGRSL peptide. This is predicted to orient the N-terminal CH3SO4 moiety of CBS 31.39 (green stick structure in Panel B) towards the fIXa S3 region. The active site Ser195 is indicated by the red surface in the center of the active site. Both dockings resulted in the reactive carbonyl of the substrate being placed adjacent to the reactive hydroxyl of Ser195 (roughly 3 Å), consistent with what would be expected for a productive enzyme-substrate complex.

Modulation of the fIXa S2 region

Our data clearly demonstrate that calcium modulates fIXa discrimination of the P2 substrate residue. This is likely due to effects on the S2 subsite that result in an increased tolerance of variation of side chain structures at the P2 position. Unlike the S3 and S4 regions of fIXa, the S2 region is more highly defined due to the more rigorous requirements of positioning of the P2 substrate residue for proper scissile bond reactivity. Available fIXa crystal structures suggest that this region is largely defined by the 99-loop (orange region in Fig 6A). Thus, our results would seem to implicate modulations of the 99-loop in the response to ionic calcium binding. This is somewhat surprising considering that only minimal structural changes were observed in the 99-loop upon calcium removal from crystals [12]. However the fIXa used in the crystal studies was a truncated and mutated form of E. coli-expressed fIXa (fIXa_3) in which part of the 99-loop had been altered (specifically, Lys98 was mutated to Thr). Additionally, the effects of calcium may have been somewhat masked in those studies as a result of calcium extraction from crystals that had been preformed using covalently-inhibited fIXa, locking the enzyme into a specific conformation. The potential consequences of these numerous significant differences from the native soluble and physiological form of fIXa are difficult to judge, and may very well result in substantial disparate conformational perturbations from those which occur in the native molecule during substrate hydrolysis. Our combined use of wild-type fIXa, peptide substrates composed of natural amino acids and an assay system based on substrate hydrolysis (rather than enzyme inhibition) can be considered to more accurately reflect the molecular changes that occur in the S2 region in response to calcium, and that are required for fIXa enzymatic function.

Modulation of the fIXa active site “upper-rim”

Our previous studies have shown that LMWH binding to fIXa allosterically modulates Lys98 in the 99 loop in such a way as to remove its hindrance of the active site, thus allowing reactivity of fIXa with the Kunitz-type inhibitor BPTI. Results obtained with small synthetic chromogenic substrates did not recapitulate this effect indicating that perhaps the movement of Lys98 may be too far removed from the immediate active site to directly affect their reactivity. However, studies with the AGRSL libraries show that LMWH binding does indeed alter substrate discrimination of fIXa; by increasing side-chain tolerance of variation at the P2 and P1' positions. This apparent discrepancy can be explained by the lack of a proper P1' side chain and the presence of small side chains at the P2 position in the chromogenic substrates, which would preclude sensing changes in both the S2 and S1' regions. Overall, the results are consistent with LMWH altering the configuration of the “upper rim” of the fIXa active site. This could be entirely due to movement of the Lys98 side chain as previously described [15]. Interestingly, the combination of calcium and heparin together negated their individual effects, suggesting that competing modulations likely occur. Indeed, although LMWH was found not to enhance hydrolysis of chromogenic substrates, we have observed a significant and consistent dampening of the rate of hydrolysis of 1 mM Spectrozyme FIXa (phenylated Gly at P2) when 10 µM LMWH (Lovenox) is added to a mixture of 25 nM fIXa and 5 mM calcium in the absence of ethylene glycol (not shown). This is likely not merely due to calcium depletion by its binding to heparin as the calcium concentration is in large molar excess (roughly 500-fold) over the LMWH (33-fold molar excess over saccharide units; Lovenox is 15 saccharide units in length).

The disparities between substrate recognition, substrate discrepancy and substrate reactivity are well recognized in enzymology, but remain ambiguous in relation. Thus, it is important to note that the results of this study do not necessarily suggest greater reactivity of fIXa towards specific substrate sequences, and conclusions regarding such substrate preferences are not warranted based on the data presented. The results do, however, demonstrate the role of plasticity in regulating fIXa function. These mechanisms may be used in part and/or in various combinations by different physiological cofactors, modulators, and substrates to induce the desired final proteolytic functionality of fIXa. The ability to artificially and differentially modulate fIXa functionality also highlights the great potential for the use of these various molecular effects in the rational design of drugs to control and modulate fIXa reactivity for treatments of either thrombosis or hemophilia.

Although hydrolysis of peptides is typically monitored using HPLC, previous studies have demonstrated the use of mass spectrometry as a higher throughput and rapid method suitable for the analysis and identification of peptide fragments in mixtures of peptides [16]. The present study demonstrates that this type of analysis is extendable to larger libraries as well as amenable to MALDI-TOF MS instrumentation. Thus, the technique is suitable for identification of known peptide masses within complex reaction mixtures, and the peaks are well removed from contaminant peaks and the DHB matrix peaks. This study provides a basis for future comparison as well as a novel methodology for approaching fIXa enzymology. Future studies of this type examining modulatory effects on fIXa using hydrolysable peptidyl substrate libraries may help to unravel the complex and subtle mechanisms involved in regulating the activity of this cryptic serine protease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; R01 HL075696 (P.F.N.).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: FIXa, factor IXa; BSA, bovine serum albumin; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; …P2, P1~P1', P2'… refer to peptide amino acid positions extending outward from the scissile bond (~) in an N-terminal (non-prime) or C-terminal (prime) direction. Enzyme subsites corresponding to these positions are typically referred to by …S2, S1, S1', S2'… etc.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.High KA, Roberts HR. Factor IX. In: High KA, Roberts HR, editors. Molecular Basis of Thrombosis and Hemostasis. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1995. pp. 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limentani SA, Furie BC, Furie B. The Biochemistry of Factor IX. In: Colman RW, Hirsh J, Marder VJ, Salzman EW, editors. Hemostasis and Thrombosis: Basic Principles and Clinical Practice. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company; 1994. pp. 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowe GD. Factor IX and thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:507–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopfner KP, Brandstetter H, Karcher A, Kopetzki E, Huber R, Engh RA, Bode W. Converting blood coagulation factor IXa into factor Xa: dramatic increase in amidolytic activity identifies important active site determinants. Embo J. 1997;16:6626–6635. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopfner KP, Lang A, Karcher A, Sichler K, Kopetzki E, Brandstetter H, Huber R, Bode W, Engh RA. Coagulation factor IXa: the relaxed conformation of Tyr99 blocks substrate binding. Structure. 1999;7:989–996. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zogg T, Brandstetter H. Activation mechanisms of coagulation factor IX. Biol Chem. 2009;390:391–400. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt AE, Bajaj SP. Structure-function relationships in factor IX and factor IXa. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2003;13:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuenschwander PF, McCollough J, McCallum CD, Johnson AE. A Conformational Change in the Active Site of Blood Coagulation Factor IXa is Associated with an Increase in Activity Upon Treatment with Ethylene Glycol. Thromb Haemost. 1997 Suppl:428. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuenschwander PF, Branam DE, Morrissey JH. Importance of substrate composition, pH and other variables on tissue factor enhancement of factor VIIa activity. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:970–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuerzebecher J, Kopetzki E, Bode W, Hopfner KP. Dramatic enhancement of the catalytic activity of coagulation factor IXa by alcohols. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00811-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sichler K, Kopetzki E, Huber R, Bode W, Hopfner KP, Brandstetter H. Physiological fIXa activation involves a cooperative conformational rearrangement of the 99-loop. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4121–4126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zogg T, Brandstetter H. Structural basis of the cofactor- and substrate-assisted activation of human coagulation factor IXa. Structure. 2009;17:1669–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuenschwander PF. Exosite occupation by heparin enhances the reactivity of blood coagulation factor IXa. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2978–2986. doi: 10.1021/bi035452d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita T, Isaacs BS, Esmon CT, Johnson AE. Derivatives of blood coagulation factor IX contain a high affinity Ca2+-binding site that lacks gamma-carboxyglutamic acid. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:5698–5704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuenschwander PF, Williamson SR, Nalian A, Baker-Deadmond KJ. Heparin modulates the 99-loop of factor IXa: effects on reactivity with isolated Kunitz-type inhibitor domains. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23066–23074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603743200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang P, Snavley DF, Freitas MA, Pei D. Screening combinatorial libraries for optimal enzyme substrates by mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:1166–1171. doi: 10.1002/rcm.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strupat K, Karas M, Hillenkamp F. 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid: a new matrix for laser desorption-ionization mass spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Process. 1991;111:89–102. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson DJ, Langdown J, Huntington JA. Molecular basis of factor IXa recognition by heparin-activated antithrombin revealed by a 1.7-A structure of the ternary complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:645–650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910144107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–61. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.