Abstract

• Aims Soil waterlogging impedes gas exchange with the atmosphere, resulting in low PO2 and often high PCO2. Conditions conducive to development of high PCO2 (5–70 kPa) during soil waterlogging and flooding are discussed. The scant information on responses of roots to high PCO2 in terms of growth and metabolism is reviewed.

• Scope PCO2 at 15–70 kPa has been reported for flooded paddy-field soils; however, even 15 kPa PCO2 may not always be reached, e.g. when soil pH is above 7. Increases of PCO2 in soils following waterlogging will develop much more slowly than decreases in PO2; in soil from rice paddies in pots without plants, maxima in PCO2 were reached after 2–3 weeks. There are no reliable data on PCO2 in roots when in waterlogged or flooded soils. In rhizomes and internodes, PCO2 sometimes reached 10 kPa, inferring even higher partial pressures in the roots, as a CO2 diffusion gradient will exist from the roots to the rhizomes and shoots. Preliminary modelling predicts that when PCO2 is higher in a soil than in roots, PCO2 in the roots would remain well below the PCO2 in the soil, particularly when there is ventilation via a well-developed gas-space continuum from the roots to the atmosphere. The few available results on the effects of PCO2 at > 5 kPa on growth have nearly all involved sudden increases to 10–100 kPa PCO2; consequently, the results cannot be extrapolated with certainty to the much more gradual increases of PCO2 in waterlogged soils. Nevertheless, rice in an anaerobic nutrient solution was tolerant to 50 kPa CO2 being suddenly imposed. By contrast, PCO2 at 25 kPa retarded germination of some maize genotypes by 50 %. With regard to metabolism, assuming that the usual pH of the cytoplasm of 7·5 was maintained, every increase of 10 kPa CO2 would result in an increase of 75–90 mm HCO3− in the cytoplasm. pH maintenance would depend on the biochemical and biophysical pH stats (i.e. regulatory systems). Furthermore, there are indications that metabolism is adversely affected when HCO3− in the cytoplasm rises above 50 mm, or even lower; succinic dehydrogenase and cytochrome oxidase are inhibited by HCO3− as low as 10 mm. Such effects could be mitigated by a decrease in the set point for the pH of the cytoplasm, thus lowering levels of HCO3− at the prevailing PCO2 in the roots.

• Conclusions Measurements are needed on PCO2 in a range of soil types and in roots of diverse species, during waterlogging and flooding. Species well adapted to high PCO2 in the root zone, such as rice and other wetland plants, thrive even when PCO2 is well over 10 kPa; mechanisms of adaptation, or acclimatization, by these species need exploration.

Keywords: Acid load, aerenchyma, bicarbonate, carbon dioxide, cytochrome c, O2 deficiency, pH regulation, metabolism, respiration, waterlogging, wetland plants

‘What is known about this?’ said the King.

‘Very little’ said Alice.

‘That is very important’ said the King.

(paraphrased from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll)

INTRODUCTION

Owing to the 104 times slower gas diffusion in water than in air, waterlogged soils are usually anoxic and by inference the slow gas diffusion will lead to accumulation of large amounts of dissolved inorganic carbon (Fig. 1; Armstrong, 1979; Jackson and Drew, 1984). Consequently, many waterlogged soils are likely to increase in PCO2 to maxima between 10 and 40 kPa (equilibrium pressure; see Appendix 1 for abbreviations and definitions of terms used within the text) and sometimes higher, but these maxima would be reached much slower than the concurrent decrease in PO2 of the soil, owing to the combination of a ∼34-fold higher solubility of CO2 than of O2 in aqueous media (Armstrong, 1979) and the conversion of a substantial proportion of CO2 to HCO3−, which will be particularly prominent at higher soil pH (Fig. 2). Hence, the present theme is clearly relevant to long-term flooding in marshes and wetlands, as well as in rice paddies; nevertheless, substantial PCO2 may also be reached in some types of soil during transient waterlogging lasting longer than several days.

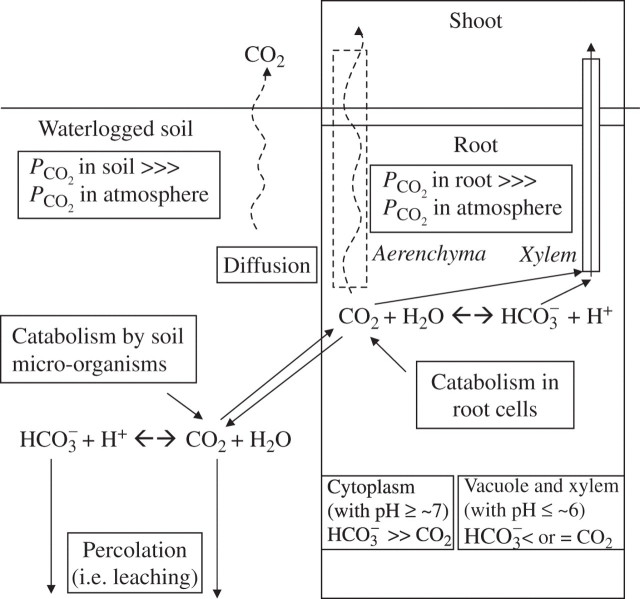

Fig. 1.

High partial pressures of CO2 occur in many waterlogged and flooded soils, particularly when pH < 7·0. Lack of ventilation leads to build up of high concentrations of dissolved inorganic carbon derived from catabolism by micro-organisms in the soil and by plant roots. CO2 and HCO3− levels in the roots will depend on the equilibrium between the input of CO2 and pathways which remove inorganic carbon to the shoots, i.e. diffusion in the gas phase of the roots and in some species by convective gas flow through rhizomes, as well as CO2 and HCO3− in the xylem stream. In species with rapid ventilation, and in a soil PCO2 of 40 kPa, PCO2 in roots is assessed at 13–26 kPa (see section in text on PCO2 in roots and rhizomes, and Table 3). Percolation may also remove dissolved inorganic carbon, at least in puddled rice soils and then would contribute substantially to mitigation of rises in soil PCO2. In some cases CO2 removal by diffusion to the atmosphere may become substantial, e.g. when PCO2 is 40 kPa and the rate of soil production is relatively low (e.g. 15 × 10–12 mol cm–3 s–1) (Appendix 2c and main text). CO2 may also be converted to CH4 (not shown), depending on soil redox (see text). Assumed is a pKa of 6·3 in the soil water. If pH of soil <6·3; then HCO3− < CO2 and increases in PCO2 will be relatively rapid. If pH of soil >6·3 than HCO3− > CO2 and increases in PCO2 will be relatively slow.

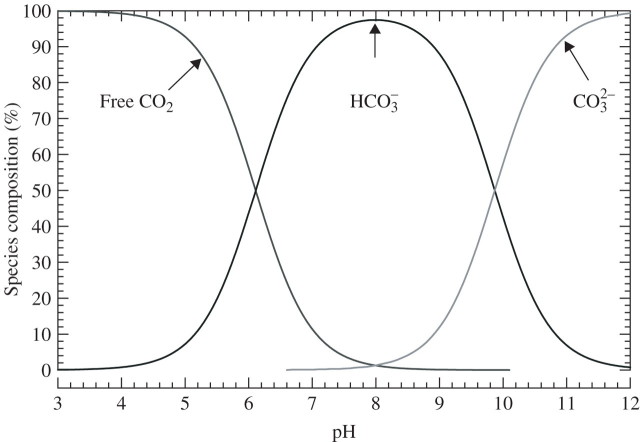

Fig. 2.

Carbonate speciation for total carbonate in a closed system, as influenced by pH. Note that at pH < 4, 100 % of the total dissolved inorganic carbon is H2CO3 (CO2 + H2O), at pH 8·0 HCO3− is at maximum and at high pH (i.e. >12) CO32– is at maximum. (courtesy of Dr John R Chipperfield, Emeritus Reader in Inorganic Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, University of Hull, Kingston upon Hull, UK). Based on the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation (Segel, 1976): pH = pKa + log(HCO3−/CO2). pKa assumed for the calculation = 6·11, and pKa2 = 9·87. The locations of the curves relative to the pH scale will depend on the ionic strength of the solution (Yokota and Kitaoka, 1985). The example shown is for the assessed ionic strength of 0.1 m in the cytoplasm (Appendix 2a). The pKa may become ∼6·3 at the low ionic strength in some soil solutions and floodwaters. In an open system, the species distributions would vary as shown, but, of course, there may be increases in dissolved inorganic carbon, so that the molar concentration of CO2 can be relatively high even when pH is above ∼7·0.

In waterlogged soils, the cortical gas-space continuum in plants provides the principal pathway for O2 flow from the air to the roots, while in many cases zones receiving sufficient O2 for oxidative phosphorylation are adjacent to anoxic zones (Jackson and Armstrong, 1999; Gibbs and Greenway, 2003). O2 movement and anaerobic metabolism have been reviewed elsewhere (for aeration: Jackson and Armstrong, 1999; Armstrong and Drew, 2002; Colmer and Greenway, 2005; for anaerobic metabolism: Armstrong and Drew, 2002; Gibbs and Greenway, 2003; Greenway and Gibbs, 2003; Jackson and Ricard, 2003). The present review evaluates the occurrence of high CO2 in waterlogged soils and the consequences for growth and metabolism of roots in such soils; as well as possible acclimatizions and adaptations to PCO2 in the range of 5–50 kPa, which have been measured in several flooded soils (Boru et al., 2003; IRRI, 2005).

Surprisingly, plant responses to high PCO2 in waterlogged-flooded soils have hardly been studied. As a gross observation, wetland plants clearly thrive during flooding. For example, paddy rice in a field at IRRI (Philippines), with water depths maintained between 50 and 100 mm above the soil surface until 7 d before maturity, yielded up to 9·3 t ha–1 (Ying et al., 1998); this soil had a pH of 6·6 and 1·4 % organic matter and, as will be described shortly, would presumably have been at high PCO2, at least when rice was in its tillering stage.

A preliminary model, presented in this review, predicts that, even at 40 kPa CO2 in the soil, PCO2 in the roots would not often rise above 13–26 kPa. Nevertheless, even in plant organs surrounded by air some tissues may reach high PCO2 owing to restricted ventilation, as found in the xylem of stems of several tree species. Maximum values are particularly relevant to our theme, as these indicate what PCO2 the cells surrounding the xylem have to tolerate. These maximum values for CO2 in the xylem depend on the species; the range for maxima in different species was found to be 4–26 kPa CO2 (McGuire and Teskey, 2004). High PCO2 can also occur in some seed pods; in chickpea, CO2 during part of the day was zero, but 7–11 kPa CO2 was reached during the night (Ma et al., 2001). These data indicate that some germinating seeds might be tolerant to high PCO2 during flooding, because they require tolerance to high PCO2 during their formation.

Mechanisms by which wetland plants acclimatize to high PCO2 in the root zone have not been elucidated, and it is not clear to what extent there are adverse effects on non-wetland plants. Nevertheless, we can speculate on the consequences of the acid load exerted by high PCO2. Taking for the quasi steady state an example of a moderate PCO2 of 10 kPa, either HCO3− in the cytoplasm would be 75–90 mm (Table 1b), running the risk of adverse effects on metabolism, or the cytoplasm would have to be below the usual value of pH 7·5 (Table 1b). By analogy, a new set point for pH of the cytoplasm (pHcyt) has been suggested for energy-deficient cells (Felle, 1996, 2005; Greenway and Gibbs, 2003). Under anoxia, pHcyt usually decreases to between 6·9 and 7·1, even in anoxia-tolerant tissues (Greenway and Gibbs, 2003); the known exception is Potamogeton pectinatus in which pHcyt only decreased to 7·3 upon imposition of anoxia (Summers et al., 2000). So, in most species, the HCO3− concentrations in the cytoplasm, at a given PCO2, should be 2·5–4 times less for anoxic than for aerobic cells. In wetland species, with root systems containing large volumes of aerenchyma, the vast majority of cells would be expected to receive adequate O2 for oxidative phosphorylation (Armstrong and Drew, 2002; Colmer and Greenway, 2005), so whether these cells would also have a lower set point for pHcyt than when the roots are in an aerobic soil/medium is an intriguing question.

Table 1.

Information on CO2 and HCO3− in aqueous solution The table gives values at a P CO2 of 10 kPa; a pressure at the lower end of the range of P CO2 to be expected in waterlogged–flooded soils and the root tissues in these soils. Detail on the derivations is given in Appendix 2a. The influences on pKa of ionic strength and temperature are from Yokota and Kitaoka (1985)

| a. CO2 concentrations in equilibrium with 10 kPa CO2 in the gas phase, and pKa of the CO2–HCO3− equilibrium | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) |

||||

| 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | |

| CO2 (mm) | 4·4 | 3·8 | 3·3 | 2·9 |

| pKa | 6·19 | 6·14 | 6·12 | 6·10 |

| b. HCO3− in cytoplasm and vacuole (mm), calculated using the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation (see caption to Fig. 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compartment |

pH |

Temperature (°C) |

|||

| 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | ||

| Cytoplasm | 7·5 | 90 | 86 | 80 | 73 |

| 7·3 | 51 | 49 | 44 | 41 | |

| 7·0 | 28 | 27 | 25 | 23 | |

| Vacuole | 6·0 | 2·8 | 2·7 | 2·5 | 2·3 |

| 5·0 | 0·3 | 0·3 | 0·3 | 0·2 | |

The scarce information on the effects of PCO2 higher than 5 kPa on metabolism is also reviewed here. Substantial information is available on exposure of fruits to high PCO2, but the relevance of these data to our theme is tenuous as these responses are confounded by effects of the climacteric.

We conclude that studies on growth and metabolism of roots at high PCO2 are required for wetland and non-wetland species, both for tissues with sufficient O2 for oxidative phosphorylation and for anoxic tissues.

PCO2 IN WATERLOGGED SOILS

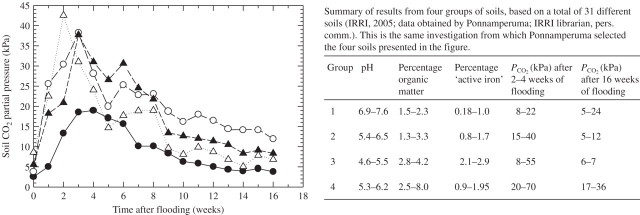

Few PCO2 values have been measured in waterlogged field soils. In one study, PCO2 increased from 1 to 30–35 kPa after 2 weeks of flooding (Boru et al., 2003; crop was soybean, pH of soil, temperature and water depth above the soil were not reported). Changes in PCO2 of soils in pots have been evaluated, with the most comprehensive data set for 31 paddy-field soils without plants (IRRI, 2005; republished data obtained by Ponnamperuma in the 1960s). As expected, rises in PCO2 were rather gradual, while PCO2 declined again after 2–4 weeks of flooding (Fig. 3). This study indicated some trends for different groups of soil (table with Fig. 3). Peaks in PCO2 remained lower when soil pH started on the alkaline side, with maxima between 8–22 kPa in the alkaline soils and 15–40 kPa in mildly acidic soils (group 1 vs. group 2 in table with Fig. 3). There are also indications that during the first weeks of flooding, PCO2 may reach as high as 55 kPa in some soils that had an initial pH of between 4·6 and 5·5 and 70 kPa in some soils with a high percentage of organic matter (groups 3 and 4, respectively, in table with Fig. 3). PCO2, in all the types of soils, declined after prolonged flooding, although some soils still contained 24–36 kPa after 16 weeks of flooding (table with Fig. 3). There are also some experimental data from pots with plants. In an experiment with rice, trends in PCO2 upon flooding were similar to those shown in Fig. 3 (Cho and Ponnamperuma, 1971). Furthermore, the importance of soil pH was demonstrated: liming a sandy loam increased the original pH of 4·8 to 6·2; the average PCO2 over 2–4 weeks of flooding was ∼40 kPa for the limed soil and ∼60 kPa for the unlimed soil (Cho and Ponnamperuma, 1971; average of the soils at 20 and 30 °C). The data of Cho and Ponnamperuma (1971) were obtained by titrations using methyl orange as an indicator, and so more direct measurements of PCO2 are required. In an experiment with wheat, the PCO2 in soil following waterlogging to the soil surface rose over 6 d from 2 to 10 kPa; after another 4 d it had risen to 14 kPa – temperature was 14 °C, organic matter was 3·3 % and initial pH was 6·3 (Trought and Drew, 1980a; PCO2 measurement using a sample of soil solution and measuring the equilibrium CO2 in the gas head-space by gas chromatography). Rises in PCO2 after the start of waterlogging were much more gradual than the decreases in PO2; PO2 commonly decreases from ∼ 21 to 0 kPa within 1–1·5 d after the start of waterlogging (Trought and Drew, 1980a). A fast decline in soil PO2 after the onset of waterlogging is consistent with calculations showing that sealing the surface would deplete the O2 present in a (previously) well-aerated soil within 2 d (Payne and Gregory, 1988).

Fig. 3.

PCO2 in flooded rice soils in pots without plants (Ponnamperuma, 1984), temperature unknown. PCO2 was calculated based on the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation; the data were obtained by sampling the soil solution and assessing HCO3− concentration using titration with methyl orange (pH range 3.0–5.0), and the pKa from the ionic strength in the soil solution. Such procedures may be in error if the soil solution contains weak acids other than CO2 (IRRI, 2005). It is not clear if, and in what way, the PCO2 values were corrected for the presence of organic acids; we have therefore not included in the table the few extremely high values measured for some soils. The value of 8 kPa in one of the soils before it was flooded (time 0) implies the soil had a very low gas-filled porosity under the experimental conditions.

The increase in PCO2 in waterlogged soils (as shown for flooded soils in Fig. 3) would be associated with CO2 evolution during catabolism by micro-organisms, mediated by organic electron acceptors, as in alcoholic fermentation (Kirk, 2004). Additional CO2 evolution would be derived from conversion of end products of anaerobic catabolism to CO2, mediated by inorganic electron acceptors, sequentially NO3−, Mn(III/IV) and then, as a principal acceptor, Fe(III) (Kirk, 2004). Usually, the CO2 production by the soil slows with time of flooding, and CO2 production is outstripped by factors decreasing PCO2, as shown after 2–4 weeks of flooding in Fig. 3.

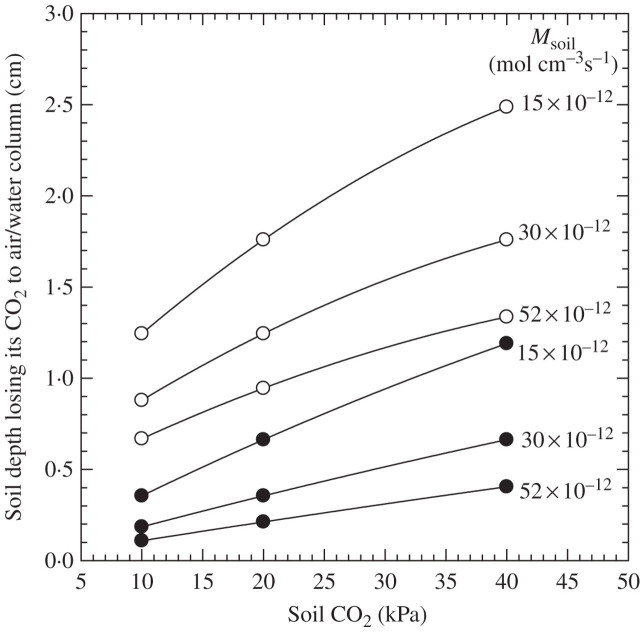

One cause of CO2 removal would be loss to the atmosphere. The soil depth from which CO2 production is lost to the atmosphere would be greater the lower the CO2 production by the soil and the higher the PCO2 in the soil (Fig. 4). The percentage production lost from the soil profile can be derived by dividing the depths shown in Fig. 4 by the depth of the soil profile producing CO2. Taking a soil depth of 200 mm, as in rice paddies, then at 40 kPa in the soil the losses would be 12·5 and 6·5 % for CO2 production rates of 15 and 52 × 10−12 mol cm–3 s–1, respectively; at 10 kPa these losses would be only 6·2 and 3·5 %, respectively. Removals would be lessened for flooded soils. For example, CO2 removals would be reduced by at least half in rice paddies, with say 100 mm stagnant water on the soil surface. Reductions would be larger the higher the rate of CO2 production by the soil and at 10 vs. 40 kPa CO2 in the soil (Fig. 4). As an example, for a PCO2 in the soil of 10 kPa, and a production rate of 52 × 10−12 mol cm–3 s–1, losses from a 200-mm soil layer would become trivial, i.e. ∼0·5 % of the rate of production. These estimates are based on a Dsoil = 0·2D0, Dsoil is the effective CO2 diffusion coefficient in the soil and D0 is the CO2 diffusion coefficient in solution. Given that the thickness of the soil layer from which the CO2 is lost to the atmosphere varies with the square root of Dsoil, losses from a soil with a Dsoil of 0·33, a usual figure for a rice paddy, would be 1·3 times greater than given above.

Fig. 4.

Soil depth losing CO2 to the atmosphere as related to soil production rates and CO2 pressures in the soil, for soils saturated to the surface (open circles) or with 100 mm of stagnant water on the soil surface (filled circles). Predictions were based on the protocols in Appendix 2c. Msoil = metabolic rate of soil organisms = CO2 production rate in soil. The percentage of CO2 production in the soil lost to the atmosphere by diffusion would be the depth of the layer from which CO2 is lost, divided by the depth of the soil profile producing CO2.

In addition to atmospheric losses, other important factors causing CO2 in the soil to decline would be precipitation of inorganic carbon as complexes of Fe (Kirk, 2004) and, in soils acidic at the start of flooding, increases in soil pH. The pH of the solution of rice paddy soils after 2 weeks of flooding usually ranges between 6·5 and 7·0, although there were cases reported when pH remained as low as 5·0 or as high as 8·0 (Ponnamperuma, 1984), so that CO2/HCO3− ratios would have been 25 and 0·02, respectively. Soils that are acidic at the start of waterlogging are likely to develop high PCO2 upon waterlogging faster than more alkaline soils (table with Fig. 3). In a survey of soils from paddy fields in Asia, the mean soil pH was ≤ 5·5 in five of 11 countries (De Datta, 1981). Soils with a pH 5·5 or lower, including acid sulfate soils which occur in the deltas of south-east Asia (De Datta, 1981), would be particularly prone to develop high PCO2, particularly as some acid soils still had a pH of between 4·5 and 6·2 at 2 weeks after the start of flooding (Ponnamperuma, 1984). Furthermore, as discussed further below, CO2 exposure of rice roots growing in acidic soils would be increased due to biogeochemical reactions following radial loss of O2 from the roots to the soil, resulting in a lower pH in the rhizosphere and hence higher CO2 concentrations relative to the bulk soil. Thus, inorganic carbon accumulation as a result of flooding would intensify any acid load imposed by the acidity of these soils.

The time sequences for changes in PCO2 in the rice paddy soils shown in Fig. 3 can be compared with the known CO2 production rates in 16 anaerobic rice soils in a laboratory experiment at 30 °C (Yao et al., 1999). We deduce that the lowest CO2 production rates over the first 14 d of waterlogging would be 1·6 µmol g–1 d. wt soil d–1 and these rates would result in an increase in PCO2 of 4·0 kPa d–1, with about double that value for the mean production rate of the 16 soils (for procedures see Appendix 3b). By comparison, the observed increases were, on average, 1·6 kPa d–1 for the four rice paddy soils studied by Ponnamperuma (1984) with a range of 0·7–2·5 kPa (Fig. 3). This discrepancy may to some extent be due to the assumption of a soil porosity of 50 % (in Appendix 3b), while some paddy soils had total porosities of 61–62 % (Painuli et al., 1988) and heavy textured soils may change into a gel-like structure upon puddling and then increase in total porosity (Greenland, 1981); values of 60–70 % are typical for these soils (G. J. D. Kirk, pers. comm.). A total porosity of 70 rather than 50 % would reduce the assessed increase in PCO2 of 4·0 kPa d–1 to 2·9 kPa d–1. The remaining substantial discrepancy between the data on CO2 production and the observed increases in PCO2 of soils can be resolved only in comprehensive experiments designed to assess CO2 production rates, pH changes during waterlogging, total porosity of the particular soils, as well as monitoring any losses of CO2 from the soil.

The key data on soil PCO2 of Ponnamperuma (Fig. 3 and its table) were only for fallow soils, so it is crucial to obtain data for soils in the field carrying stands of rice. Roots would make a substantial contribution to the changes with time in PCO2 of the soil, in the early phase after the start of flooding CO2 production may contribute to the rate of rise in dissolved inorganic carbon in soils. Of equal importance, in the quasi steady state, the gas-space continua in the plants might vent, to the atmosphere, considerable amounts of CO2 that enter from the soil, in addition to the CO2 produced by the root's catabolism. Some indication for the importance of this venting can be gained from data on CH4 emissions: in a field ‘covered with rice’, cutting the rice stems below the water surface showed that up to 94 % of the methane emissions from the soil–root system was via the gas-space continua from roots to shoots (Holzapfel-Pschorn et al., 1986). In this quasi steady state, soil PCO2 will be determined by both the CO2 production by the soil and ventilation via the root system. That ventilation via plants depends on the density of roots of the stand was indicated by the very similar CH4 emission rates between soil with paddy rice and bare soil during the first 7 weeks after transplanting, when there would not yet be a dense stand (Holzapfel-Pschorn et al., 1986). Even when the bulk soil has reached a PCO2 of 40 kPa, the amounts of CO2 removed via the air space continuum would tend to be less than 10 % the CO2 production, as long as the density of roots is low (for details see next section).

The need for comprehensive data on PCO2 in waterlogged soils is amplified by further factors affecting PCO2, which make extrapolation of the data by Ponnamperuma (1984) to field soils quite uncertain. First, CO2 production is strongly dependent on organic matter (Rowell, 1988). Secondly, in rice soils, there is often some percolation, reaching 5–10 mm d–1, which would remove part of the produced CO2 (Rowell, 1988). Other percolation rates were 1–8 mm d–1 in montmorrilonitic clay at IRRI, Los Banos, as affected by different degrees of puddling and amounts of water use during puddling (Painuli et al., 1988) and 0·5–4·5 mm d–1 for six paddy soils in the Philippines (Kirk, 2004). That removal of dissolved inorganic carbon by percolation may be a major factor in limiting increases in PCO2 in the root zone is assessed for a 200-mm soil layer in a puddled rice field, by assuming that the soil is fallow, is at 30 °C and that percolation, at 5 mm d–1, would be the only cause of CO2 removal. Using the calculation given in Appendix 2c, assuming a pKa of 6·3 in the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation (caption to Fig. 2), it is assessed that a soil at 40 kPa CO2 would lose by percolation 8, 12 and 24 × 10−12 mol cm–3 s–1 at pH 6·5, 6·75 and 7·0, respectively, i.e. removal would exceed or at least be a substantial proportion of the CO2 production rates of 15–50 × 10−12 mol cm–3 s–1 assumed below in Table 3. The leaching would also slow down the increases in PCO2 with time and be more important at lower temperatures because of the higher solubility of CO2 (Table 1a). In contrast to observations for methane, ebullition would make only a small contribution to CO2 removal, because CO2 is ∼ 20 times less volatile than methane (Kirk, 2004). Thirdly, CO2 may be converted to CH4, with the redox potential for the equilibrium at −125 mV for a soil with pH of 5·0, and at −245 mV for a soil with pH of 7·0 (Rowell, 1988). In rice paddy soils in the quasi steady state, the ratio between production of CO2 and CH4 ranged between 0·28 and 0·93 (Yao et al., 1999). Nevertheless, even gas bubbles from marshland in the USA with 20–70 kPa CH4 still contained 5·5–10 kPa CO2 (Shannon et al., 1996), indicating that the bulk soil had about the same PCO2.

PCO2 IN ROOTS AND RHIZOMES

When the rhizosphere is high in dissolved inorganic carbon, its uptake into root cells will be dominated by the high permeability of plant membranes to CO2, as CO2 is a weak acid and plant cells rapidly take up many weak acids in the undissociated form (Guern et al., 1991; for CO2 see Heber et al., 1994). The presence of an undissociated acid in the medium is called an ‘acid load’ (Bown, 1985; Guern et al., 1991), as the dissociation of weak acids in the cell will tend to acidify the cytoplasm. Intensity of the ‘acid load’ imposed by exogenous total dissolved inorganic carbon in the soil solution will depend on the pH of the soil solution, as pH determines the HCO3–CO2 equilibrium (Fig. 2). This crucial point was demonstrated using carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) callus cells; O2 uptake was stimulated two-fold by adding pure CO2 to a solution buffered at a pH of 5·7, resulting in a PCO2 of 5·5 kPa (Palet et al., 1991). Similarly, addition of HCO3−+K+ increased O2 uptake, but this stimulation decreased with increasing pHext and became negligible when pHext was 7·8, when the CO2/HCO3− ratio would be 0·03 (Palet et al., 1991). However, to conclude from these results that the effects on metabolism were due to CO2, rather than to HCO3− (Drake et al., 1997), is misleading. Whether the metabolic consequences of high PCO2 are due to the ensuing high concentrations of endogenous CO2 or to the inevitable rises in HCO3− in the cytoplasm needs further experimentation.

The only data on PCO2 in roots of plants in waterlogged soils have been published for whole root systems of Quercus nigra (water oak) and Fraxinus pennsylvanica (green ash), at 9 months after flooding to 100 mm water depth. The highest value was 10 kPa CO2 for green ash (Good and Patrick, 1987). However, this value would be an over estimate because inorganic carbon was extracted in a solution with a pH of 2·5; taking this into account, our estimates of PCO2 in these root systems, based on the data provided by Good and Patrick (1987), are between 2·8 and 5·4 kPa (for details see Appendix 4a). Obtaining reliable data on PCO2 in roots of plants in waterlogged soils is a high priority for future research.

Measurements of PCO2 in gas sampled from lacunae of rhizomes, petioles and culms of partially submerged wetland species have shown that PCO2 in these organs is at least several kPa (Table 2). Stem internodes near the soil surface of rice growing in 0·8 m of water reached 4–10 kPa CO2 (Table 2). Most of this CO2 had presumably emanated via diffusion from the roots; the only other possible source was from catabolism within the stem, as the floodwater was ruled out given that the PCO2 of the floodwater was 1·5–3 kPa when PCO2 in the internodes was 8–10 kPa (Setter et al., 1987). In this system, PCO2 in the soil will be high, so that there will be a diffusion gradient between the roots and the internodes, i.e. roots would be substantially higher in PCO2 than the internodes. Rice has no substantial convective flow (Beckett et al., 1988), so the venting of CO2 to the atmosphere via the internodes and shoots would be dependent on diffusion. Regardless, even in species with convective gas flow through their rhizomes, high PCO2 values have been observed (i.e. despite the potential of rapid ventilation); in one case PCO2 reached 10 kPa (Table 2). In the floating-leaved water lily, Nuphar luteum, in 1·2 m of water, 85 % of the CO2 flowing up the petiole was fixed by photosynthesis (Dacey and Klug, 1982a). Photosynthesis using CO2 derived from the roots is not further reviewed herein.

Table 2.

Measured values of P CO2 and P O2 in rhizomes, or stems, of wetland plants

| Species and water depth | Organ | PCO2 (kPa) | PO2 (kPa) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phragmites australis; water 20 cm above soil surface. Observations 14 d after installing the needles for sampling, which would have disturbed the steady-state PCO2 | Rhizomes, 0–20 cm depth | 2·5 | 15 | Brix (1988) |

| Rhizomes, 50–80 cm depth | 7·2 | 3 | ||

| Nuphar (water lily) a floating leaved species; in a lake with 1.5 m of water | Rhizomes, 4–6 cm under sediment | 8·2–10·3 | 8·7–5·6 | Dacey (1981) |

| Nuphar; in pond with 1 m of water | surface | 2·1–3·4 | 10–15.3 | Dacey and Klug (1982b) |

| Deep-water rice in field with 0.8 m water | Stem internodes, near soil surface | 4–10 | 8–12 | Setter et al. (1987) |

In the absence of reliable data, the value of PCO2 that may occur in roots of waterlogged plants can be speculated for two cases: (1) when PCO2 in the soil is higher than in roots, which is probably the case in soils that are waterlogged for longer than ∼7 d; and (2) when PCO2 in the roots is higher than in the soil, which would occur at least at the start of waterlogging. Before discussing these two cases it is relevant to discuss the possibility that root tissues in the mature zones of many wetland species may be ‘insulated’ from the soil, due to a ‘barrier’ to gas diffusion in the external cell layers, as found for O2 (Armstrong, 1979; Colmer, 2003a).

Roots with a low permeability to radial gas diffusion in basal zones

Basal zones of roots of many wetland species have a rather tight barrier to radial O2 loss (Armstrong, 1979; Colmer, 2003a), for example in rice roots at more than 20 mm from the apex (Colmer, 2003b). The key question for our theme is whether this barrier would also have a high resistance to CO2 diffusion. The layers with very low permeability to radial O2 loss are presumably associated with suberin in the exodermis. Further information on how solutes and water permeate through these layers, if at all, is scant. There are data on water permeability for rice roots, on isolated outer parts of the roots, which did contain suberin in their exodermis (Ranathunge et al., 2004). However, these data are of doubtful relevance to our theme as these roots were raised in aerated nutrient solution and therefore presumably had no strong barrier to O2 exchange. More relevant are some data for roots of Phragmites australis, which in their zone of very low permeability to O2 contained some passage areas (‘windows’) of about 1 mm in diameter, which did show significant radial O2 loss (Armstrong et al., 2000); such areas are likely to be also entry areas for water uptake. The radial O2 diffusion to the medium would be opposite to the water flow, and occur via diffusion whereas the water movement occurs via mass flow. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that when CO2 is higher in the root than in the environment (case 2, discussed below), CO2 loss to the root environment would, as for O2, be greatly restricted. By contrast, when CO2 is higher in the soil than in the root, CO2 entry into these root sections may be higher than predicted (case 1, discussed below), as fast water flows during the day may conceivably facilitate CO2 uptake by mass flow, i.e. restrictions to CO2 influx may be pronounced only at night. Such CO2 flow would be particularly prominent if water flow was through aquaporins, which may also have a high permeability for CO2 (Tyerman et al., 2002). On the other hand, if aquaporins have a low permeability to CO2, the high permeability of the lipid bilayer to CO2 would be dominant (Tyerman et al., 2002), while the effect of water flow on CO2 intake would be greatly reduced.

Case 1: PCO2 higher in the soil than in the root

Values for PCO2 that may occur in roots in waterlogged soil have been assessed using a preliminary model as described in Appendix 3a, and the predictions are shown in Table 3. These calculations also provide the diameter of the soil core from which CO2 would flow from the soil into the root. The latter is relevant to ecosystems during long-term flooding, as the wider the core from which CO2 flows to a root, the more likely it is that cores around several roots will overlap and hence gradually lower the PCO2 in the soil, owing to ventilation to the atmosphere via the gas-filled channels in the roots.

Table 3.

Predictions for development of root CO2 partial pressures in waterlogged soils with a bulk soil PCO2 of 40 kPa as a result of root and soil CO2 production

| Column number | 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 | 5 |

6 |

7 | 8 |

9 |

10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of different characteristics |

Soil CO2 production rates |

Root radius |

Root length and initial tip CO2 |

Root porosity |

Temperature |

|||||

| Root radius (cm) | 0·06 | 0·06 | 0·06 | 0·03 | 0·06 | 0·06 | 0·06 | 0·06 | 0·06 | 0·06 |

| Root porosity (%) | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 16 | 4.2 | 35 |

| Root length (cm) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 30 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Soil temperature (°C) | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 15 |

| Soil CO2 production rate (10–12 mol cm–3 s–1) | 52 | 30 | 15 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 15 |

| Initial CO2 in root tip (kPa) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| CO2 input into root from soil (10–12 mol s–1) | 97·2 | 88·5 | 79·6 | 58·8 | 74·9 | 52·9 | 88·5 | 79·8 | 52·1 | 90·3 |

| R(si)PCO2 in root required to ventilate influx from soil (kPa) | 3·6 | 3·3 | 2·9 | 8·7 | 8·3 | 5·9 | 3·3 | 6·5 | 16·1 | 3·5 |

| Resultant RPCO2 in 10 mm root tip (kPa) | 13·6 | 13·3 | 12·9 | 18·7 | 18·3 | 25·9 | 13·3 | 16·5 | 26·1 | 13·5 |

| Radius of soil core from which influx is derived (cm) | 0·90 | 0·97 | 1·30 | 0·79 | 0·89 | 0·75 | 0·97 | 0·92 | 0·75 | 1·39 |

The radius of the soil core from which CO2 flows into the root is also predicted. These two predictions are shown in the two bottom rows. Bulk soil at 40 kPa CO2, and effective soil CO2 diffusivity (Dsoil) = 0.2D0. Effects of Dsoil other than 0.2D0 are shown in Fig. 6. The default data set in column 2 is given in bold type, and changes in parameters from the default values are shown also in bold type for the various other columns. Columns 1–3 show the effects of differences in soil CO2 production rate [assessed from Yao et al. (1999); see Appendix 3b]; column 4 (cf. column 2), effects of decreased root radius; column 5 (cf. column 2), effects of increased root length; column 6 (cf. column 5), effects of increased root length and initial root tip CO2 concentration; columns 7–9, effects of root porosity; column 10 (cf. column 2), effects of soil temperature (lower temperature decreasing soil CO2 production and altering CO2 diffusivities and solubilities in root and soil). Data are from our own preliminary model (see text and Appendix 3a).

The preliminary model is based on the assumption that CO2 influx occurs only into the 10-mm root tip; this assumption was made for several reasons. It is the simplest model, and the predictions are particularly relevant for wetland species including rice, which, as argued earlier, might have a layer of low permeability to CO2 in the mature root zones. Furthermore, the predictions are the most conservative possible, therefore giving the minimum values of PCO2 likely to occur in roots of plants in waterlogged soils at a given PCO2 in the soil; these are the best values in a review which argues the unproven notion that roots in waterlogged–flooded soils often contain high CO2.

In Table 3, we have used an example where Dsoil is given by the relationship Dsoil/D0=0·2, where 0·2 is the product of the fractional porosity (ɛ) and a gas-space tortuosity factor (τ < 1). Results with other values of Dsoil/Do are considered after discussing the values presented in Table 3. Another assumption for Table 3 is that PCO2 in the bulk soil is 40 kPa. This value was chosen because the few data available indicate that this PCO2 would prevail in several waterlogged–flooded soils, at least for several days, so the plants need at least to survive at this particular level. Three rates of CO2 production in the soil were chosen, to evaluate the impact of this parameter on the resulting PCO2 in the root. These rates are based on the rare, but comprehensive, set of data for CO2 production in the laboratory, for 16 anaerobic rice paddy soils, from China, the Philippines and Italy, at 30 °C (Yao et al., 1999). CO2 production rates chosen were 15, 30 and 52 × 10−12 mol cm–3 soil s–1, as observed between 8 and 10 d after the start of anaerobiosis, when soil below pH 7·0 will be approaching high levels of PCO2. Subsequently, CO2 production declined and in the quasi steady state reached 0·38–5·41 × 10−12 mol cm–3 soil s–1 (calculated from Yao et al., 1999). It remains unknown whether this decline is due to feedback by the high PCO2 attained, depletion of readily decomposable organic matter or other causes.

The estimated PCO2 in the root which would be required to ventilate the CO2 influx from the soil (R(si)PCO2) to the atmosphere should be added to an estimate for PCO2 associated with ventilation of CO2 produced by the root's own catabolism (R(rc)PCO2), to obtain total PCO2 in roots (RPCO2). The minimum value for R(rc)PCO2 can be assessed by assuming a respiratory quotient of 1·0. If there were no net CO2 flux between the root and the soil, the PCO2 gradient in the gas-space continuum would be of the same magnitude as the observed PO2 gradient, but of course in the opposite direction. Any anaerobic CO2 evolution, as in ethanolic fermentation, would increase these levels of CO2.

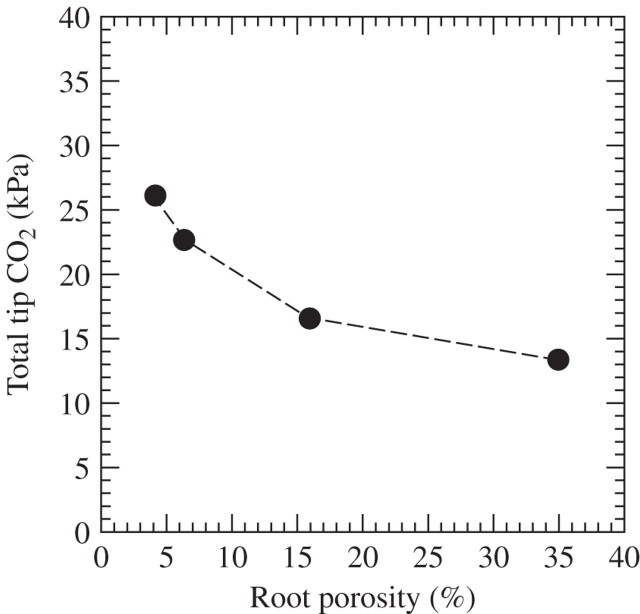

Overall, the predictions show that the PCO2 in the root (RPCO2) generated by a combination of net influx of CO2 from the soil (R(si)PCO2) and CO2 produced by the root catabolism (R(rc)PCO2) is greatly influenced by the percentage gas-filled porosity of the roots, and to a lesser extent by root diameter and length. Surprisingly little effect arises from three-fold differences in the rate of CO2 production in the soil. The effects of different effective diffusion coefficients for CO2 in soil will be discussed after considering cases 1·1 and 1·2.

Case 1·1: predictions for roots of wetland species with high root porosity, when in flooded soil

Most of the cases given are for rice, with the gas-filled porosity in the roots set at 35 %. Furthermore, it was assumed the roots were 100 mm long and their diameter was 0·6 mm, unless stated otherwise. Predictions for various conditions are:

(1) Soil production increases of CO2 by as much as 3·5-fold only increased the predicted RPCO2 in the 10-mm root tip from 12·9 to 13·6 kPa (Table 3, columns 1–3). By contrast, the diameter of the soil core from which CO2 flows into the root is 45 % larger at the lower CO2 production rate in the soil (Table 3, columns 1 and 3).

(2) Smaller root diameters of 0·3 mm would increase RPCO2, for example in the 10-mm tip of a 100-mm-long root to 18·7 kPa compared with 13·3 kPa for a root diameter of 0·6 mm, while decreasing the predicted diameter of the soil core from which CO2 flows into the root by ∼20 % (Table 3, columns 2 and 4).

(3) Rice roots can reach a length of ∼ 300 mm in flooded fields (Kirk, 2003), for which RPCO2 in the 10-mm root tip would be 18·3 kPa, rather than the 13·3 kPa predicted for a 100-mm-long root (Table 3, columns 5 and 2).

(4) The conclusion in condition (3) was based on the assumption that the CO2 production rate of 300-mm-long roots would result in an R(rc)PCO2 of only 10 kPa in the 10-mm tip. However, in 300-mm-long roots, the PO2 in the 10-mm root tip is more likely to be close to zero and hence the R(rc)PCO2 at which CO2 ventilation in the gas-space continuum balances the CO2 production in catabolism is assessed at 20 kPa. Then, still assuming the bulk soil PCO2 is at 40 kPa, the RPCO2 would be 25·9 rather than 18·3 kPa (Table 3, columns 5 and 6), while the R(si)PCO2 (i.e. the component of RPCO2 due to influx from the soil) would drop from 8·3 to 5·9 kPa CO2 (Table 3, columns 5 and 6), as a result of the smaller concentration gradient between the bulk soil and the root.

(5) Because many wetland species thrive in cool climates, predictions on RPCO2 were also made for 15 vs. 30 °C. For this comparison, the lowest rate of CO2 production 15 × 10−12 mol cm–3 soil s–1 was used for the value of 15 °C, as the rate of CO2 evolution from soil has a Q10 of ∼2 (Yao and Conrad, 2000; Bouma et al., 1997). The predicted PCO2 in the 10-mm root tip was nearly identical at 15 and 30 °C (Table 3, column 10 vs. 3): in the soil solution a 20 % lower diffusion coefficient at 15 than at 30 °C is outweighed by the 50 % increase in solubility of CO2, while diffusion in the gas-space continuum is 10 % slower at 15 than at 30 °C (Armstrong, 1979).

Overall, these predictions for roots of rice and other wetland plants, which have in their mature zones an impermeable barrier to O2, and hence possibly to CO2 exchange, indicate that when the bulk soil PCO2 is 40 kPa, the 10-mm tips of their roots, which have no impermeable barrier to gas exchange, would reach at least 13 kPa and rise to 26 kPa PCO2 in some cases. Equally importantly, the model predicts that PCO2 in the roots of these species would remain well below the 40 kPa CO2 in the soil: the PCO2 assumed in Table 3 to be in the bulk soil.

Case 1·2: predictions for roots with porosities lower than 35 %, when in flooded soil

Gas-filled porosities in roots of several species are smaller than in rice (Justin and Armstrong, 1987; Colmer, 2003a). RPCO2 was estimated for 100-mm-long roots and the bulk soil at 40 kPa; porosities of ∼ 15 % would still limit RPCO2 to 16·5 (Fig. 5). At lower porosities, RPCO2 rises rather steeply, although even at the low porosity of 4 %, RPCO2 is still about 14 kPa below the PCO2 in the bulk soil. These lower porosities would be representative for non-wetland plants in waterlogged soil; for example, maize reaches a root porosity of 16 % (Yu et al., 1969). Importantly, as with other non-wetland species, maize lacks a barrier to O2 exchange along its roots (Darwent et al., 2003). So, the predicted RPCO2 will be substantially above the 16·5 kPa given for a root porosity of 16 % in Fig. 5, where it is assumed that only the 10-mm tip is permeable to CO2. These considerations show that roots of non-wetland species are likely to reach substantially higher internal PCO2 during waterlogging–flooding than those of wetland species. High root porosity leads to larger radii for the soil cores from which CO2 flows into the root (Table 3, columns 7–9); the amount of CO2 lost from the soil would be 1·7 times higher at a root porosity of 35 % than at 4·2 %.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between root porosity and RPCO2, when the bulk soil is at 40 kPa PCO2. Predictions were derived using the protocols in Appendix 3a. Conditions assumed are: CO2 production by the soil of 30 × 10−12 mol cm–3 s–1, PCO2 in the root required to ventilate CO2 production in the root of 10 kPa, root radius of 0·6 mm, root length of 100 mm and soil temperature of 30 °C. Other conditions are as in Table 3. Note that the PCO2 in the root due to influx from the soil would be the values shown minus 10 kPa.

In conclusion, when PCO2 in the soil is higher than in the roots, PCO2 in the roots can be surprisingly much lower than in the soil: depending on the PCO2 in the bulk soil and plant characteristics such as percentage gas-filled porosity, root length and resistance to CO2 movement across the external cell layers of roots, the estimated PCO2 in the roots ranged between 13 and 26 kPa. Variations in CO2 production rates in the soil have little effect on PCO2 in the roots, as these are compensated for by changes in the soil volume from which CO2 flows into the roots (Table 3, columns 1–3). Nevertheless, soil CO2 production rates remain relevant to the ecosystem of flooded fields because (1) at the start of waterlogging high rates of CO2 production will lead to rapid increases in PCO2 of the soil, and hence in roots, and (2) in the longer term the radius of the soil core from which CO2 enters roots would determine the impact that vegetation has on soil PCO2; soils with low rates of CO2 production and therefore a larger radius of soil core from which CO2 enters roots (Table 3, columns 1–3) might, when root density becomes high, intensify any gradual removal of CO2 produced in the soil via gas-space continua in the roots to the atmosphere. Let us assume that in a stand of rice, young, 100-mm-long roots would be 26 mm apart. This figure is chosen because at 40 kPa CO2 in the soil and a production rate of 15 × 10−12 mol cm–3 s–1 the cores from which CO2 flows into the root would be just touching. At this root density, the removal of CO2 to the atmosphere from a 200-mm soil layer with a PCO2 of 40 kPa would be 1·1 and 4 % of the CO2 produced at rates of 50 and 15 × 10−12 mol cm–3 s–1, respectively (protocols given in Appendix 2d). Such losses will be much lower if the PCO2 in the bulk soil has reached only 20 kPa, always assuming the same root density; for example, at 15 × 10−12 mol cm–3 s–1 the removal via the gas space continua would only be 1·6 % of the rate of production (assessed using the protocols given in Appendix 3a). These calculations are based on a simplified case; in reality, CO2 would also enter via lateral roots and the removal as a percentage of that produced by the soil would tend to increase. Nevertheless, this increase would be mitigated by the decrease in CO2 concentration gradient between the tip and the atmosphere, associated with the entry of CO2 into root sections closer to the surface.

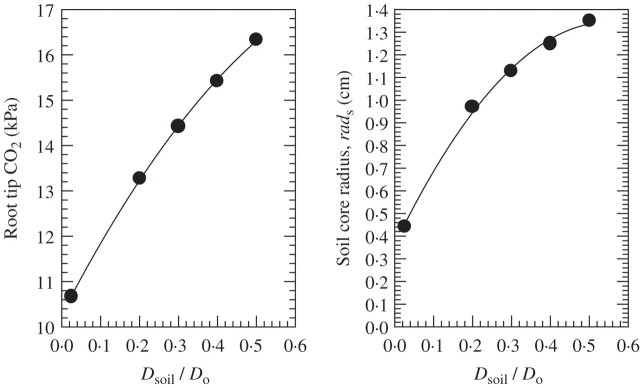

Effect of soil porosity (ɛ) and tortuosity (τ). There is, at present, insufficient information on the effective diffusion coefficient for CO2 in waterlogged soils. Different values of the effective diffusion coefficient (Dsoil) than the 0·2 taken in the calculations presented in Table 3 would give substantial changes in R(si)PCO2, as affected by the various characteristics of the soil and root systems; nevertheless, these changes would be only in degree, not in kind. Total porosities (ɛ) range between 40 % for sands and 50 % for clays (Ahuja et al., 1999), while in some puddled rice soils ɛ can be as high as 60–70 % (Kirk, 2004). Assuming these materials are not ‘cemented’, the tortuosity factor (τ) would be ∼ 0·66 (Penman, 1940), and similar values of 0·5–0·7 were found for the impedance factor in rice soils based on diffusion of 36Cl− (Kirk et al., 2003; the impedance factor is close to the tortuosity factor, τ). Tortuosity will increase (i.e. τ will decrease) with decreasing soil porosity (ɛ) (Kirk et al., 2003). Dsoil is derived by multiplying the product of τ and ɛ with D0, from the diffusion coefficient in aqueous solution. The product of τ and ɛ (i.e. Dsoil/D0) is 0·28 for sands, 0·33 for clays and 0·3–0·5 for the puddled rice soils. Taking the mean value of Dsoil/D0 for the puddled rice soils of ∼0·4, R(si)PCO2 would be 57 % higher than at a Dsoil/D0 of 0·2, and the radius of the soil core from which CO2 flows into the root would increase by ∼25 % (Fig. 6); nevertheless, RPCO2 would increase only from 13·3 to 15·4 kPa. By contrast, at least for the drained state, Currie (1965) has shown that crumbs (aggregates) in clays are in a ‘consolidated-cemented’ state and that these crumbs have a mean Dsoil/D0 of ∼0·1 (range 0·025–0·156). If these crumbs persisted following waterlogging, the pathway of CO2 diffusion may be mainly through these crumbs to root surfaces, which line these crumbs. If the Dsoil/D0 was 0·1, rather than 0·2, there would be a reduction of 42 % for R(si)PCO2 (calculated according to Appendix 3a), while the reduction in RPCO2 would be only 10 %, with a 30 % smaller radius of the soil core from which CO2 flows into the root (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Plots for root tip CO2 (RPCO2 in kPa) and soil core radius (rads) from which CO2 enters roots in waterlogged soil as predicted using the model presented in Appendix 3a, for a range of values of Dsoil/D0, and the following conditions: root length = 100 mm, site of entry into the root only the 10-mm root tip, CO2 production rate = 30 × 10−12 mol cm–3 soil s–1, root fractionial porosity = 0·35. This is the combination of soil and plant characteristics shown in column 2 of Table 3. The substantial effects of Dsoil/D0 (i.e. the product of soil porosity and tortuosity) on RPCO2 at the combination of soil and plant characteristics used would also apply to other combinations of characteristics of the soil–plant system (shown in Table 3); the magnitude of the effects on RPCO2 will differ in degree, but not in kind.

Role of HCO3− diffusion in the soil on CO2 entry into roots. This theme will only be considered qualitatively, as more precise analysis will require detailed modelling of the complex interplay between HCO3− and CO2 diffusion. Possible relevance of HCO3− diffusion depends upon both the soil and the rhizosphere pH. Assuming first that pH is uniform between the bulk soil and rhizosphere, then any HCO3− diffusion would not alter the picture derived by considering CO2 diffusion alone, as the rate constant of the uncatalysed rate of CO2 hydration is 0·037 s–1 (Raven and Newman, 1994), i.e. much faster than the rate of diffusion prevailing in the soil. However, radial O2 loss, as occurs from root tips and laterals in many wetland plants (Armstrong, 1979; Colmer, 2003a), would complicate the picture. Radial O2 loss will tend to lower the pH of the rhizosphere, by oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, which will precipitate, and by NH4+ removal, either by its uptake or by nitrification with subsequent uptake of NO3− by the roots (Begg et al., 1994; Kirk, 2004). Both oxidation of Fe2+ to insoluble Fe(III) and NH4+ removal will reduce the cation concentration in the rhizosphere and hence lower pH (Gerendas and Schurr, 1999). The Henderson–Hasselbalch equation shows that under such conditions, PCO2 would be higher in the rhizosphere than in the bulk soil, while a gradient in HCO3− towards the root surface would be equal in magnitude to the CO2 gradient from rhizosphere to bulk soil, i.e. CO2 will tend to diffuse from the rhizosphere to the bulk soil, while HCO3− would flow towards the root (Begg et al., 1994). (Note that, for convenience, this deduction has assumed an absence of CO2 uptake by the root.) Thus, the boundary conditions postulated for the model in Appendix 3a would no longer apply. Here we consider only the extreme case where the presented model would give grave errors. In Iloilo sand with rice plants, the pH at 3 d after the start of waterlogging was 5·0 at the root surface compared with 6·5 at 10 mm from the root surface (Begg et al., 1994). The Henderson–Hasselbalch equation predicts that at equilibrium, PCO2 would be 2·5 times greater at the root surface than in the bulk soil, while during CO2 uptake by the root, the diffusion of dissolved inorganic carbon to the root will presumably nearly entirely depend on the large HCO3− gradient in the direction of the root surface. Consequently, CO2 uptake by the rice roots in Iloilo sand is likely to be substantially faster than predicted by the model used in the present paper, albeit by less than expected from the high CO2 level in the rhizosphere because the diffusion of HCO3− is 40 % slower than that of CO2 (Kirk, 2004). The application of these deductions to the present model are uncertain because it is as yet unknown what the pH gradient would be around the 10-mm extending root tip. Nevertheless, substantial pH gradients might be expected despite the shorter exposure of the soil to the influence of the root, associated with the continued extension of the root tip, as this shorter exposure would be counteracted by high rates of processes tending to reduce the pH of the rhizosphere, such as vigorous uptake of NH4+ (either as the cation or as NO3− after nitrification) (see Colmer and Bloom, 1998) and oxidation of Fe2+ (Kirk, 2004), stimulated by the substantial radial O2 loss to the rhizosphere surrounding the apex (Armstrong, 1979; Colmer 2003a). Note that this complication is much less serious in better-buffered soils; for example, in Maahas soil the pH was 7·24 at 10 mm from the root and 7·1 next to the root (Kirk, 2004).

Effects of xylem flow along roots, and of convective gas-flows through aerenchyma in rhizomes. PCO2 in roots might be lower than indicated above because the CO2 efflux to the shoot may be increased due to rapid transpiration. For the xylem stream, the amount of dissolved inorganic carbon removed from the roots can be calculated using the flow rates and anatomy given by Armstrong (1979), while the amount would also depend on the pH of the xylem sap (Table 1b). In a survey of three tree species, pH of the xylem sap ranged between 5·6 and 6·5 (McGuire and Teskey, 2004). In Ricinus communis the pH of the xylem sap fluctuated between 6·0 round midnight and 5·3 at midday (Gerendas and Schurr, 1999). At pH 5·3, the ratio of HCO3−/CO2 would be 0·1; even so, substantial dissolved inorganic carbon would be removed at fast transpiration; assuming that roots had a PCO2 of 10 kPa, the xylem stream would remove 40 % of the CO2 produced in aerobic catabolism. Substantially more dissolved inorganic carbon might exit in the xylem stream if its pH was higher; for example, at pH 6·5 the HCO3−/CO2 ratio would be 1·6 (cf. equation in caption to Fig. 2), and then nearly all the CO2 produced by the root's aerobic catabolism would be removed in the xylem stream. Estimates of the same order of magnitude can be derived from transpiration ratios presented by Ludlow (1976); dissolved inorganic carbon removal was estimated to range between 20 and 100 % of production (procedures given in Appendix 2b). As the combination of CO2 production by the roots and CO2 influx from the soil may give rise to as much as 26 kPa PCO2 in the root (Table 3, column 6), much higher than the example of 10 kPa used above, substantial diurnal fluctuations in PCO2 may occur when transpiration is high during daylight hours as compared with when transpiration is low during the night.

Possible diurnal fluctuations in PCO2 in roots, as dependent on xylem flow, would be accentuated in species with convective gas flow through their rhizomes; for example, Phragmites australis has a PCO2 in its rhizomes close to 0 kPa during the day, whereas at night, when gas movement is by diffusion, PCO2 was 6 kPa (Chanton et al., 2002). Similar fluctuations for CH4 (Chanton et al., 2002) demonstrated that these diurnal changes were due to differences in gas flow, not related to photosynthesis. During darkness lasting 50 h, PCO2 in rhizomes of P. australis increased, but only in those at depths of 0–60 cm, not when the rhizomes were at greater depths in the mud (Brix, 1988). Furthermore, the deductions made here require a caveat; as discussed earlier CO2 influx into roots may become substantial during rapid water flow, and if so, the predicted fluctuations in CO2 would be dampened. Thus, the hypothesis that diurnal cycles of transpiration cause diurnal cycles in PCO2 in the rhizomes and root system needs testing; a comprehensive test would include rates of transpiration, pH of the xylem sap and convective gas flow through rhizomes, in addition to internal PCO2 measurements.

Case 2: PCO2 lower in the soil than in the root

This situation is likely to occur at the start of waterlogging before PCO2 in the soil builds up, or when O2 deficiency occurs in swelling clays, with a low gas-filled porosity which can be aggravated by soil compaction (Blackwell et al., 1985). In such compacted soils CO2 might still be ventilated through the inter-crumb pore space, as the water-filled soil capillaries can be relatively short; thus, diffusive fluxes can still be substantial, and much faster for CO2 than for O2 in view of the earlier mentioned 34-fold higher solubility of CO2 versus O2, so that the ΔPCO2 will be much smaller than the ΔPO2 (Greenwood, 1973; Payne and Gregory, 1988). Similarly, with low PCO2 in the soil, effluxes of CO2 from roots will only require relatively small differences in ΔPCO2 between the gas-space within the roots and the external solution. This crucial point is best demonstrated using data for excised maize roots, in which the only fluxes are between root and external solution. In these roots, the ΔPO2 between solution and the middle cortex was 21·1 – 14·4 kPa=6·7 kPa (Gibbs et al., 1998). Let us assume that the respiratory quotient is 1·0, the flow of both O2 and CO2 is through the same pathway though in the opposite directions, while the main resistance would be in the liquid steps (i.e. through cells and through any water in extracellular spaces). Then, the required efflux of CO2 to the root medium would only require a ΔPCO2 of 6·7/26·5 = 0·25 kPa; the denominator is 26·5 rather than 34 because in water the ratio of diffusion coefficients of CO2 to O2 is 0·78 (Armstrong, 1979). Similarly, only low ΔPCO2 between cortex and stele are predicted; based on the ΔPO2 of 4 kPa between inner cortex and outer stele in aerated maize roots (Gibbs et al., 1998), the ΔPCO2 would be only 0·15 kPa.

In conclusion, detailed modelling of the factors determining PCO2 in plant roots is clearly needed, but will be warranted only when data on PCO2 in soils and root tissues become available. Such measurements, combined with modelling, would elucidate the question of to what extent the root tissues of waterlogged plants experience high PCO2.

EFFECTS OF HIGH PCO2 ON ROOT GROWTH

Effects of high PCO2 on root growth have been studied in solution culture for flooding-tolerant rice, and the much less flooding-tolerant soybean (Boru et al., 2003). Treatments were imposed at 14 d after germination and continued for another 14 d. Rice grew as well with its roots in anaerobic as in aerated solutions. Response to CO2 was only studied for plants in anaerobic solutions. Root dry weight of rice was not affected by 15 kPa CO2, but was reduced by 25 % at 50 kPa CO2 (Boru et al., 2003). The longest roots, a more refined indicator of root growth than dry weight, were 15 % shorter at 15–30 kPa CO2 than with anaerobiosis alone. The length was reduced by a further 15 % at 50 kPa CO2. These rice roots have a large volume of aerenchyma and hence would receive large amounts of O2 from the shoot, so might not experience a combination of high PCO2 and anoxia. Consistent with the results for rice given by Boru et al. (2003), rice plants survived exposure of their roots to 100 kPa CO2, even at pH 4·0 (Tanaka and Navasero, 1967); nevertheless, dry weight of similarly treated rice roots was decreased by ∼45 %, compared with a mere 7 % due to anoxia without CO2 (Rao and Mikkelsen, 1977).

In contrast to rice, soybean (under the same experimental protocol) root length reduced by 60 % in anaerobic solutions, while this inhibition was increased to 78, 89 and 94 % when the anaerobic flushing gas contained 15, 30 and 50 kPa CO2, respectively (Boru et al., 2003). Consistent effects, although usually less severe, were found for dry weight and various characteristics of shoot growth. It is relevant that a much larger part of the root system of soybean than of rice might have been anoxic. It would also be of interest to establish whether high PCO2 was adverse to the zones receiving sufficient O2 for oxidative phosphorylation, to the anaerobic zones or to both. As pointed out by Boru et al. (2003), part of the adverse effect of high PCO2 during anaerobiosis of the nutrient solution could be related to its inhibition of ethylene action, as indicated by a pronounced reduction in the number of adventitious roots in soybean. Consistently, 10 kPa CO2 reduced aerenchyma in adventitious roots of rice by 8–40 % (Jackson et al., 1985). Confirmation of the results reported by Boru et al. (2003) is important for several reasons. Foremost, Boru et al. (2003) applied the high PCO2 suddenly; it has been discussed above that such sudden increases are quite atypical for soils in the field and, as shown in a later section, sudden increases in PCO2 will result in transient, drastic, decreases in pHcyt, followed by at least partial recovery. Severe adverse effects during the ‘shock’ of sudden exposure to high PCO2 may well occur, and these might have long-term repercussions on growth; indeed, it is impressive that rice tolerated the combination of these shocks, and subsequent exposure to 50 kPa CO2 for 14 d. A second important limitation of using solution culture, for the evaluation of the consequences of high PCO2 in waterlogged soil, is that these solutions are usually flushed with gas and hence are turbulent. Consequently, the endogenous PCO2 in the roots will be fairly close to the exogenous PCO2; so this technique is unsuitable to ascertain the tolerance of various species in waterlogged soils, as the soil solution will be stagnant, and therefore the endogenous PCO2 will be lower the larger the gas-space continuum in the roots (Fig. 5), which is species-dependent. Summing up, the available data make a convincing case for tolerance to high PCO2 for rice roots. On the other hand, whether intolerance to high PCO2 in soybean roots is a component of the well-known intolerance to waterlogging of this species needs to be tested with more gradual increases in PCO2.

Of particular relevance to our theme are the few investigations on the interaction between high PCO2 and low PO2. Studies on wheat show that adverse effects of high PCO2 on root growth either did not occur, or were not as severe, at low compared with at ambient PO2 (Huang et al., 1997). Exposure of wheat roots to 10 kPa CO2 at 20 kPa O2 reduced total root length by ∼30 %; however, at 5 kPa O2 the 10 kPa CO2 did not aggravate the adverse effects of 5 kPa O2 (Huang et al., 1997). Interestingly, with the combination of 10 kPa CO2 and 5 kPa O2, the length of the axes of the seminal roots was reduced less than at either 10 kPa CO2 or 5 kPa O2 alone (Huang et al., 1997); in other words, at 5 kPa O2, 10 kPa CO2 stimulated seminal root elongation by 25–35 %. Similarly, 10 kPa CO2 did not aggravate the already large growth reductions of wheat roots in N2-flushed nutrient solution (Trought and Drew, 1980b). The results from Huang et al. (1997) present an enigma because, at 5 kPa O2, substantial parts of the roots would still receive sufficient O2 for oxidative phosphorylation; for 6-mm root tips of wheat this proportion was assessed at ∼50 % (Thomson et al., 1989). It is not clear why these aerobic zones, which presumably are critical to the performance of the roots, would not be impaired in their function by high PCO2, even though high PCO2 clearly reduced growth in aerated solutions. A similar mitigation of the adverse effects of high PCO2 by concurrent exposure to low PO2 was found for germinating maize (Table 4). Interestingly, a genotypic difference in tolerance to 25 kPa CO2 was consistent with their tolerance to flooding (Cerwick et al., 1995). This is so far the only recorded case in which differences in flooding tolerance within a species were associated with the ability to cope with high PCO2 rather than with low PO2 in the medium. In contrast to these responses by wheat and maize, in soybean the earlier described adverse effect of 30 kPa PCO2 on growth in anaerobic solutions (Boru et al., 2003) was not found in soil flushed with gas mixtures containing 30 kPa CO2 and 20 kPa O2 (Grable and Danielson, 1965). Thus, in soybean, high PCO2 may have adverse effects only when the roots are in anaerobic solution, and this possible interaction needs to be tested in the same experiment and with the same genotype.

Table 4.

Germination of maize in rolls of moistened paper at 25 kPa P CO2 at 5 and 20 kPa O2

| Treatment | Flooding-tolerant genotype | Flooding-intolerant genotype |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage germination relative to controls | ||

| 25 kPa CO2 + 20 kPa O2 | 81 | 47 |

| 25 kPa CO2 + 5 kPa O2 | 97 | 77 |

| 5 kPa O2 | 98 | 96 |

Data are expressed as percentage of germination at 20 kPa O2 and 0 CO2 in the flushing gas (data from Cerwick et al., 1995).

The genotypes are assigned as being ‘tolerant’ or ‘intolerant’ data based on experiments in soil flooded for 72 h, when germination of the tolerant genotype was reduced by 40 % and of the intolerant genotype by 85 %.

The interaction between high PCO2 and low PO2 requires comprehensive information on the effects of high PCO2 on aerated roots; unfortunately there is very little information on this topic. In flooding-tolerant Rumex palustris, exposure to 10 kPa CO2 for 2 h in aerated solution reduced the elongation rate of primary roots by 20 % (Visser et al., 1997). By contrast, dramatic injury resulting from exposure to modest PCO2 (∼2 kPa) has been reported for roots of some cacti. The cortical cells of the cacti were considered to be dead within 3–6 h following exposure to CO2 as low as 2 kPa (Nobel and Palta, 1989; Palta and Nobel, 1989). The same period of exposure to anoxia was not fatal. Based on these and other data, Nobel and Palta (1989) concluded the extreme intolerance of these species to PCO2 of 1–3 kPa was the likely reason for their restriction to well-aerated sandy soils. Enigmatically, in the leaves of the same and a related species as used by Nobel and Palta (1989), PCO2 increased to 1·3–2·5 kPa during the day, when CO2 is liberated from malate, which is part of the normal circadian rhythm (Luettge, 2002). In view of this apparent difference in tolerance between leaf and root tissues, confirmation of the results of Nobel and Palta would be useful (some further reservations on the experiments by Palta and Nobel are given in Appendix 4b).

Further information on the tolerance of roots to high PCO2 is scant and contradictory. In experiments lasting a few days, PCO2 of 6·5–8·5 kPa stopped root growth in pea, bean, sunflower and broad bean (Stolwijk and Thimann, 1957) and cell division in broad bean (Williamson, 1968). By contrast, PCO2 at 5–6·5 kPa had little effect on roots of oat (Stolwijk and Thimann, 1957) and soybean (Grable and Danielson, 1965). Possible reasons for these discrepancies include differences in tolerance between various species, contamination of ethylene in the CO2 supply (suggested by M. Cramer) and insufficient prevention of CO2 enrichment of the air around the shoots (Cramer, 2002). So, new experiments are needed to evaluate the effects of high PCO2 in the root zone on plant growth.

EFFECTS OF HIGH PCO2 ON METABOLISM

We have found no information on the effects of high PCO2 on root metabolism of waterlogging-tolerant species, and with the exception of large reductions in CO2 evolution in the roots of the cacti mentioned earlier (Nobel and Palta, 1989; Palta and Nobel, 1989) no information on non-wetland species (for further comments on the experiments on cacti, see Appendix 4b).

Responses of fruit and vegetables exposed to high CO2 during storage might provide an indication of the likely responses by plant cells. In harvested fruits and vegetables, respiration was usually reduced by high PCO2, while injury was postulated in the cases when respiration was increased (Herner, 1987; Mathooka, 1996). Such data are not reviewed in detail here because the results for the vegetables are merely descriptive and the results for the fruits may be confounded by delay in the climacteric and possible interactions with ethylene (Mathooka, 1996). More relevant might be some papers on the response of non-growing cell cultures and protoplasts of pear fruit (Kerbel et al., 1990 and Lammertyn et al., 2001, respectively). Decreases in respiration of these cells and protoplasts were 25 and 40 % for 5 and 15–20 kPa CO2, respectively, and this degree of inhibition was not affected by PO2 between 2·5 and 21 kPa (Lammertyn et al., 2001); this is a similar response to that described earlier for growth of roots of intact wheat plants. As these preparations were derived from pear fruits, there is still the confounding possibility of physiological changes associated with the climacteric. Consistently, these cultures responded similarly to the intact fruit, in respect both to high PCO2 (Kerbel et al., 1990L; ammertyn et al., 2001) and to ethylene (Brady and Romani, 1988).

Substantial data are available on the effects of 10–50 kPa CO2 on photosynthesis by leaves of a range of species (Heber et al., 1994); high CO2 was used to simulate acid rain. This response of photosynthesis to high PCO2 is only peripheral to our theme, because submerged leaves are seldom exposed to PCO2 higher than 10 kPa. In a flooded rice field, the PCO2 was 3 kPa at 0600 h, but due to increases in pH of the waters associated with CO2 uptake during photosynthesis, CO2 concentrations became very low at midday (Kirk, 2004); the effects of high PCO2 on photosynthesis will thus be transient. Furthermore, as shown in a large survey of ‘CO2-rich’ freshwater streams in Denmark, the highest values of CO2 (1·5–3 kPa) occurred only in 2 % of the streams (Sand-Jensen and Frost-Christensen, 1998). However, in sheltered, slightly polluted lakes in the Netherlands PCO2 ranged between 3·5 and 10 kPa (Prince and de Guia, 1986). Furthermore, leaves may not respond to high CO2 in the same way as roots, given that adverse effects on CO2 fixation may be particularly severe as the pH of the stroma of the chloroplasts is ∼8·0 (Alberts et al., 2002), i.e. at a given PCO2 the HCO3− concentrations would be approx. three-fold higher than in the cytoplasm (Table 1b). Nevertheless, in view of the scarcity of studies on metabolic responses to high PCO2, this seminal paper by Heber et al. (1994) remains valuable to this review, as it provides ideas on how plant metabolism may cope with high dissolved inorganic carbon. In some experiments by Heber et al. (1994), CO2 was added at the start of a light period, quasi steady-state rates of photosynthesis in leaves of Symphytum officinale were then reached at 1 min after transfer to 2 kPa CO2, but this lag was 15–30 min after transfer to 20 kPa CO2. There were remarkable differences in tolerance to high CO2 among species; times to reach a new quasi steady-state photosynthesis were sometimes much longer than in Symphytum officinale. Furthermore, quasi steady-state rates of photosynthesis of spruce and barley leaves were not affected by 20 kPa CO2, while in maize leaves photosynthesis was inhibited by 40 and 80 % at 10 and 20 kPa CO2, respectively (Heber et al., 1994), values consistent with intolerance to 25 kPa CO2 of some maize genotypes during germination (Table 4).

Changes in metabolism are now be discussed, first in relation to the imposed acid load (i.e. a tendency to acidify the cytoplasm) and then in relation to direct effects of CO2 and/or HCO3− on enzymes.

Acid loads

At equilibrium, the vacuole, which usually has a pH of 5–6 (Guern et al., 1991), would contain a mere 0·3–2·5 mm HCO3− for each 10 kPa CO2 (Table 1b). By contrast, pHcyt is usually ∼7·5 in aerobic cells (Xia and Roberts, 1996; Ratcliffe, 1997), so each increase of 10 kPa PCO2 in the roots would result in an additional 75–90 mm HCO3− in the cytoplasm (Table 1b). Hence, 10 kPa PCO2 presents a large ‘acid load’ as the buffering capacity of the cytoplasm in cells, other than leaf cells, is 20–80 meq l–1 (pH unit)–1 (Kurkdjian and Guern, 1989).

The response to high PCO2 will be first considered for the quasi steady state, when high PCO2 is predicted for most roots in waterlogged soil, provided soil pH is not too far above the pKa of the CO2–HCO3− equilibrium, say not above ∼7·0. Subsequently, responses to sudden changes in PCO2 will be considered. Responses to such rapid changes in PCO2 of the environment are seldom relevant to waterlogging in the field, because as discussed earlier PCO2 in soils only increases by 0·05–0·1 kPa h–1 (calculated from Fig. 3 and Trought and Drew 1980a), which would result in an increase of a mere 0·45–0·9 mm HCO3− h–1 in the cytoplasm, assuming its pH was 7·5. Nevertheless, responses to sudden changes in PCO2 remain of interest for four reasons:

Rather rapid fluctuations in dissolved inorganic carbon in plant tissues might occur, as argued earlier, due to fluctuations in transpiration, as well as in convective gas flows through rhizomes.

Sudden exposure to high PCO2 would occur during the planting of paddy rice in puddled fields, already flooded for 2–3 weeks (Rowell, 1988). Presumably, the roots would be suddenly exposed to high PCO2 and this shock would coincide with a need for healing of the root systems.

Data obtained following sudden changes in PCO2 provide evidence that pH stats have become engaged (as discussed below).

Sudden changes in exogenous PCO2 have been the practice in nearly all nutrient solution experiments, making discussion of the consequences of such ‘shocks’ relevant to interpretation of these experiments.

Mechanisms of acclimatization to high PCO2

There are three possible mechanisms of acclimatization to high endogenous PCO2, all related to either mitigating or coping with formation of HCO3− in the cytoplasm. By contrast, the only way to minimize CO2 concentrations in cells of roots exposed to high soil PCO2 is, as discussed earlier, via rapid ventilation to the shoots in the root gas-space continuum (Table 3 and Fig. 5). First, the biochemical pH stat, i.e. removal of organic acids, or production of organic cations, would provide cation balance for the increased level of HCO3−. Secondly, a biophysical pH stat would via uptake of cations (usually K+) provide the charge to balance the HCO3−, as discussed in general for pH regulation by Ullrich and Novacky (1990). These two mechanisms would not change the HCO3− concentration, which will be determined by the pH of the cytoplasm and the CO2 concentration attained in the tissues, as determined by rates of production during catabolism, influx from the environment and ventilation via the gas-space continua within roots. The third mechanism would mitigate the increases in HCO3− in the cytoplasm by a decrease in the set point of the pH of the various cytoplasmic compartments, which would greatly reduce the formation of HCO3− at a given CO2 concentration (Table 1b) and hence reduce its possible effects on metabolism. At moderate PCO2, such a mechanism may avoid the need to engage the pH stats, provided the cytoplasm had a high buffering capacity. All three mechanisms have their limitations and it is therefore likely that in tissues reaching 30–40 kPa CO2, the three mechanisms may have to act in concert if acclimatization is to be achieved.

(1) The quasi steady-state

(a) A decrease in the set point of pHcyt. A decrease in pHcyt would greatly lessen the increase of HCO3− by decreasing the ionization of H2CO3 (Table 1b). For the CO2–HCO3− equilibrium, even a relatively small decrease in pH from 7·5 to 7·3 would result in a decrease of 45 % in the equilibrium HCO3− concentration (Table 1b). In embryos of Artemia, the brine shrimp, pHcyt was reduced by increases in PCO2, but even the smallest decrease from pH 7·9 to 7·3, due to an increase in PCO2 by 10 kPa, reduced respiration by 50 % (Busa and Crowe, 1983). Accordingly, these authors concluded that decreases in pHcyt in Artemia triggered metabolic arrest, which is well established during anoxia for this and some other animal species (Hofmann and Hand, 1990). Whether the set point in pHcyt can decrease without slowing metabolism remains unknown. Regardless, lowering the set point of pHcyt will have a limit: in anoxic plant tissues substantial decreases of pHcyt below ∼7·0 are associated with compromised metabolism and eventual death (Xia and Roberts, 1996; Greenway and Gibbs, 2003).

(b) The biochemical pH stat. This stat would merely replace endogenous organic acids by HCO3− and therefore have few further repercussions for metabolism. The maximum amount of organic acids that could be removed would be about 80 meq ml–1 of cytoplasm; this value is based on the K+ level in the cytoplasm of barley roots (Leigh, 2001), which is mainly balanced by organic anions, but a lower value is likely as some of the organic anions would be essential for intermediary metabolism.

(c) The biophysical pH stat. For each rise of PCO2 by 10 kPa, such a stat would have to increase the concentration of monovalent cations by 75–90 mm, mainly K+, assuming the set point of pHcyt remained at 7·5. However, the increase in cation concentration is unlikely to cope completely with the large acid loads likely to occur in a number of situations for roots in waterlogged soils: K+ in the cytoplasm of barley roots was 80 mm (Leigh, 2001), and substantial increases in K+ above this concentration have adverse effects on metabolism. For example, 170 mm K+ (as acetate) gave a 80 % reduction in 35S-methionine incorporation into proteins by an isolation from wheat germ (Flowers and Dalmond, 1993). This paper is particularly relevant to the present theme, because it indicates genetic diversity in tolerance to high K+ concentrations, with K+ optima of 100–150 mm in five non-halophytes, 125–200 mm in two halophytes and 200–275 mm in the extreme halophyte Suaeda maritima (Flowers and Dalmond, 1993). Such data need further scrutiny, as the isolations were supplemented with post-ribosomal supernatant of wheat germ and showed polypeptide elongation, but little initiation of new polypeptide chains (Flowers and Dalmond, 1993).