Abstract

Photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy (PAOM) is a new retinal imaging technology that offers the unique capability to measure optical absorption in the retina. Because PAOM is compatible with optical coherence tomography, scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, and autofluorescence imaging, registered multimodal images can be acquired from a single device at comparable resolution for comprehensive anatomic and functional retinal characterizations. Therefore, PAOM is anticipated to have applications in both research and clinical diagnosis of many blinding diseases. The authors explain the basic principles of the photoacoustic effect and imaging. Then, different types of photoacoustic microscopy are introduced and compared. Finally, the current status of photoacoustic imaging in animal eyes is presented and the prospects of future development of PAOM are suggested.

INTRODUCTION

Photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy (PAOM) is a branch of photoacoustic microscopy, a non-invasive, three-dimensional microscopic imaging modality based on the photoacoustic (PA) effect. PAOM differs from conventional ophthalmic imaging modalities by its unique contrast mechanisms. Existing ophthalmic imaging modalities, including fundus photography, optical coherence tomography (OCT),1,2 confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (cSLO), autofluorescence imaging, and fluorescein angiography, all rely on the detection of light either reflected from the retinal tissues or re-emitted from an endogenous chromophore or an extrinsic contrast agent. In contrast, PAOM detects the PA waves generated by the absorption of pulsed illuminating laser light to form an image. As a result, PAOM is capable of imaging the physiologically specific optical absorption contrast in the retina, which is missing in all existing ophthalmic imaging modalities.

The challenge in measuring optical absorption in scattering media such as biological tissues is that once the photons are absorbed, they cannot be directly quantified by imaging technologies that rely on back-traveling photons. Quantifying optical absorption is critical for measuring hemoglobin oxygenation in retinal vessels and pigment density in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Several groups have investigated methods based on hyperspectral fundus imaging to quantify the optical density of retinal vessels,3,4 but the results are not satisfactory due to influences from the complicated optical paths of back-scattered photons and the melanin concentration in the RPE.

PAOM was first introduced in 20105 and has since achieved high-speed, high-resolution in vivo imaging of the vasculature of the retina and the pigmentation of the RPE in small animals. The latest progress in PAOM includes integration with other imaging modalities such as OCT, autofluorescence imaging, and adaptive optics to achieve multimodal imaging of the retina. Because the technology is completely new for the ophthalmic imaging community, this review attempts to present an overall picture of the current status of PAOM.

PHOTOACOUSTIC IMAGING

Basic Principles of Photoacoustic Imaging

PAOM measures the optical absorption properties in the retina through the PA effect. The PA effect was first reported in 1880,6 and the initial purpose was to achieve the first “wireless” voice communication. In the late 1980s, researchers started to use the PA effect for biomedical imaging.7 The exponential increase in PA imaging research started around 2000.8 Review articles about the history of PA imaging can be found in the literature.8-10

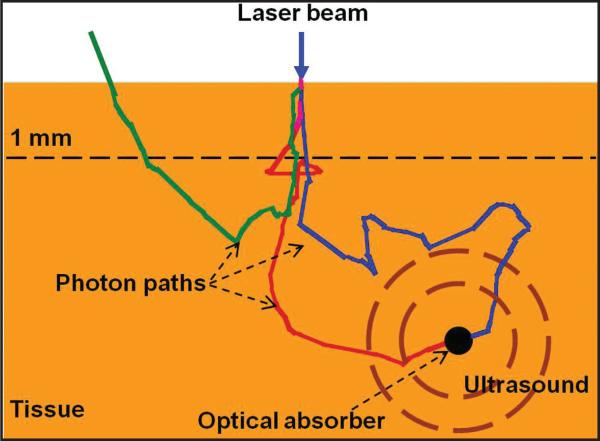

The physical principle of the PA effect is shown in Figure 1. Typically, monochromatic laser light pulse (in the nanosecond level) is used to illuminate a tissue sample. When photons travel inside the tissue, they can be both scattered and absorbed. Photons lose their original propagation direction quickly due to strong optical scattering in the tissue. When photons are absorbed by a strong optical absorber such as a blood vessel, as shown in Figure 1, the absorbed optical energy is converted into heat and generates a transient temperature rise, which leads to thermal expansion and generates ultrasonic waves. The ultrasonic waves are detected with an ultrasonic transducer to form an image. To efficiently convert the illuminating optical energy to ultrasound, the laser illuminating time needs to be shorter than both the tissue's thermal relaxation time and stress relaxation time.11 Laser pulses with duration of a few nanoseconds will usually satisfy such requirements.

Figure 1.

Illustration of photoacoustic effect in tissue.

To form an image, time-resolved detection of the induced PA wave is required. The amplitude of the detected PA signal is primarily determined by the energy deposition, which is a product of local optical fluence and the optical absorption coefficient. The time of arrival of the detected PA signal to the ultrasound detector is used to determine the spatial locations of the optical absorbers in the axial direction. There are two major branches of PA imaging: photoacoustic tomography (PAT)12,13 and photoacoustic microscopy (PAM).14-16 PAT uses either an ultrasonic array or a scanning ultrasonic transducer and sophisticated inverse reconstruction algorithms to achieve three-dimensional imaging of deep tissues. Currently, the major applications of PAT are the imaging of blood vessels in the brain,13 breast,17 skin,18 and internal organs.19 In comparison, PAM uses a focused ultrasonic transducer to localize the sources of the PA signals and requires no image reconstruction.

Mechanical Scanning PAM

Two types of PAM have been developed: ultrasonic-resolution PAM (UR-PAM) and optical-resolution PAM (OR-PAM).20-24 UR-PAM is designed for deep-tissue imaging, where an illumination laser is diffusively delivered to the tissue and a focused ultrasonic detector is used to detect the induced PA signals. The lateral resolution of UR-PAM is determined by the ultrasonic focal spot and the axial resolution is determined by the ultrasonic center frequency and bandwidth.

In OR-PAM, both optical illumination and ultrasonic detection are strongly focused and arranged in a confocal geometry, and the image forming process is the same as for UR-PAM. The goal of OR-POM is to work in a comparable depth range of other optical microscopic technology but to provide optical absorption contrast. The lateral resolution of OR-PAM is, therefore, determined by the optical focal spot and the axial resolution is still determined by the ultrasonic parameters. Typical lateral and axial resolutions in OR-PAM are 5 and 15 μm, respectively, at an ultrasonic center frequency of 75 MHz and a bandwidth of 100 MHz, where single capillaries were imaged in vivo with high contrast-to-background ratio.20

In both UR-PAM and OR-PAM, during imaging the optical illumination and ultrasonic detection is raster-scanned mechanically and a water bath is required to maintain ultrasonic coupling. The detected time-resolved PA signals are converted to depth-resolved A-lines based on the acoustic propagating velocity in tissue (approximately 1.5 mm/μs). By further aligning all of the A-lines according to the corresponding location of the focused ultrasonic transducer, a volumetric image is generated.

Optical Scanning Photoacoustic Microscopy

Although existing PAM has achieved extraordinary microvasculature imaging in skin, it is impractical for ophthalmic imaging because the ultrasonic detector must be in contact with the subject through a water bath. Mechanical scanning of the optical and ultrasonic components is not only slow, which is unsuitable for in vivo retinal imaging, but also makes PAM incompatible with current ophthalmic imaging modalities such as OCT and SLO, which limits its capability for multimodal imaging.

To prepare PAM for in vivo retinal imaging, in 2009 we developed the laser-scanning optical resolution PAM (LSOR-PAM).25 In LSOR-PAM, the ultrasonic detector is kept stationary and only the optical focus is raster-scanned. The advantages include a much higher scanning speed, the capability to perform sophisticated scanning patterns, and, more importantly, suitability for retinal imaging and compatibility with OCT26 and SLO.27

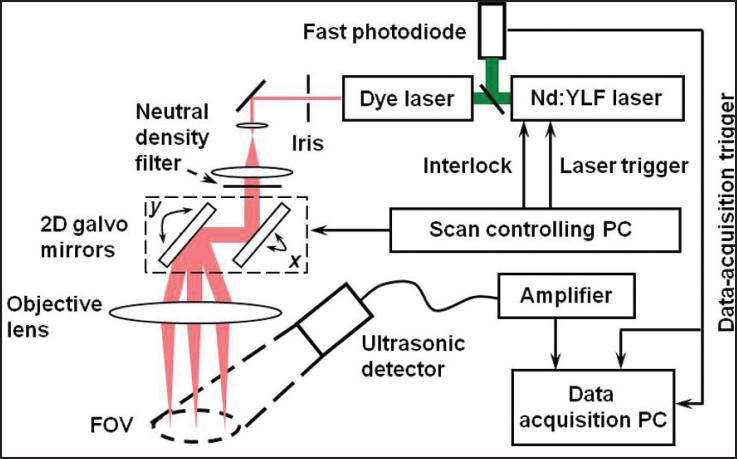

The schematic of the LSOR-PAM is shown in Figure 2. A tunable dye laser pumped by an Nd:YLF laser system (pulse duration: 6 ns) was used as the irradiation source. The laser system can operate with a pulse repetition rate of up to 5 kHz with an optical wavelength tuning range between 540 and 900 nm. The output laser light from the dye laser was spatially filtered by an iris and expanded to reach a beam diameter of 8 mm. After being attenuated by a neutral density filter, the expanded laser beam then passed through an x-y galvanometer scanner and a 60-mm focal length objective lens. An analog-output board synchronized the laser triggering and the optical scanner. The induced PA waves were detected by a commercial unfocused ultrasonic transducer (center frequency: 10 MHz; bandwidth: 80%; active element diameter: 6 mm). The detected PA signals were first amplified by a wideband pre-amplifier and then digitized and stored by a data acquisition board controlled by the data acquisition PC for further processing. A fast photodiode detected the laser pulses and triggered the data acquisition to avoid the impact of laser jittering. The energy of each laser pulse was also recorded from the photodiode to compensate for the pulse energy instability. The sampling rate of the data acquisition board was 200 MS/s and the PA signals were recorded for 3 μs. No signal averaging was employed during data acquisition. The parameters of LSOR-PAM are given in the table.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the laser-scanning optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy experimental setup. (Reprinted with permission from Xie ZX, Jiao SL, Zhang HF, Puliafito CA. Laserscanning optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Lett. 2009;34:1771-1773).

TABLE.

System Parameters of LSOR-PAM

| Laser Pulse Energy | Field of View | Lateral Resolution | Axial Resolution | CNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4 nJ | 6 mm | 7.8 μm | 50 μm | 26 dB |

LSOR-PAM = laser-scanning optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy; CNR = contrast-to-noise ratio.

Figure 3 shows an in vivo image of microvasculature in the ear of a Swiss Webster mouse, which is a maximal amplitude projection (MAP) of the three-dimensional data. In this experiment, a fixed laser wavelength of 580 nm was used. LSOR-PAM shows comparable capabilities in imaging microvascular structures as OR-PAM.20 Up to seven orders of branching can be observed and the smallest vessel is imaged by a single pixel in the image, which indicates a vessel diameter of approximately 7.8 μm. Comparing with confocal OR-PAM, the contrast-to-noise ratio in LSOR-PAM is lower due to the non-focused ultrasonic detection and the field of view is fundamentally constrained by the sensitivity of the ultrasonic detection.25

Figure 3.

Laser-scanning optical resolution-photoacoustic microscopy image of vasculature in a Swiss Webster mouse ear in vivo. Two pairs of parallel veins and arteries are highlighted by 1 and 2. PA = photoacoustic. (Reprinted with permission from Xie ZX, Jiao SL, Zhang HF, Puliafito CA. Laser-scanning optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Lett. 2009;34:1771-1773).

PA IMAGING OF THE EYE

Three groups reported their independent works on PA imaging of the eye in early 2010.5,28,29 This section summarizes the results from these three groups.

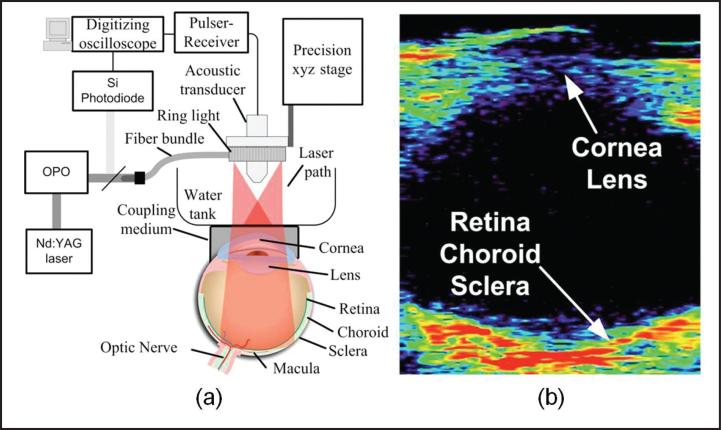

De la Zerda et al. imaged a rabbit eye in vivo28 using a mechanical scanning UR-PAM; the experimental setup is shown in Figure 4a. As previously described, mechanical scanning requires a water bath to maintain ultrasonic coupling; therefore, a water tank was placed on top of the rabbit eye coupled by ultra-sound gel. The illuminating optical wavelength was 740 nm to avoid melanin absorption and the focused ultrasonic detector had a center frequency of 15 MHz. Figure 4b shows the cross-sectional (B-scan) image of the rabbit eye, in which the whole eyeball was imaged. Due to limited ultrasonic spatial resolution, it is difficult to recognize retinal features from the B-scan image. Furthermore, the full three-dimensional image acquisition took 90 minutes and a single B-scan took 2 minutes. Due to physical contact and extended imaging time, the animal was killed after imaging.

Figure 4.

Ultrasonic-resolution photoacoustic microscopy imaging of a rabbit eye in vivo. (a) Schematic of the experimental system; (b) cross-sectional photoacoustic image of the image rabbit eye. (Reprinted with permission from de la Zerda A, Paulus YM, Teed R, et al. Photoacoustic ocular imaging. Opt Lett. 2010;35:270-272).

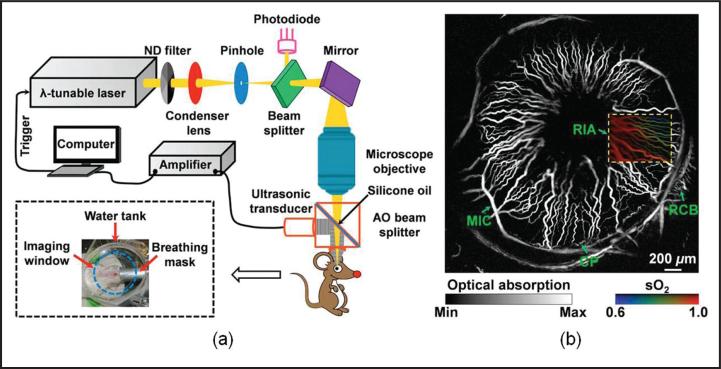

Hu et al. conducted in vivo imaging of the microvascular network in the iris of a mouse eye29 using OR-PAM. As shown in Figure 5a, the illuminating laser was strongly focused by a microscope objective lens to achieve a lateral resolution of 5 μm. The center frequency of the focused ultrasonic detector was 75 MHz and the optical wavelength was tuned to emphasize hemoglobin absorption for angiography (Fig. 5b). Single capillary was resolved with a fitted diameter of approximately 6 μm. Based on the differential molecular extinction coefficient spectrum of oxy-hemoglobin and deoxy-hemoglobin, multi-wavelength OR-PAM was further conducted to extract the hemoglobin oxygen saturation (sO2)15,16,30-32 in vessels, as shown by the color insert in Figure 5b. Despite the impressively high image quality, the image acquisition took approximately 2 hours, which was limited by the mechanical scanning. Physical contact of the water bath with the cornea was required and the animal had to be killed after imaging. Due to the intrinsic limit of the system design, mechanical scanning PAM is unable to image the retina with high spatial resolution and high imaging speed.

Figure 5.

Optical resolution-photoacoustic microscopy imaging of a mouse eye in vivo. (a) Schematic of the experimental system and (b) maximum amplitude project image of the vascular network in the anterior segment. AO = acousto-optical; CP = ciliary process; MIC = major iris circle; RCb = recurrent choroidal branch; RIA = radial iris artery. (Reprinted with permission from Hu S, Rao b, Maslov K, et al. Label-free photoacoustic ophthalmic angiography. Opt Letters. 2010;35:1-3).

It is clear that to image the retina the PA scanning system not only must be fast, it also must not come into physical contact with the cornea. We developed the OCT-guided photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy (PAOM) to address these needs5 and to achieve multimodal retinal imaging. Multimodal imaging takes advantage of combining different contrast mechanisms to provide comprehensive anatomical and functional information of the retina. Combining OCT with PAOM can potentially provide retinal anatomy, retinal blood flow, and retinal sO2 from a single instrument.

OCT-GUIDED MULTIMODAL PAOM FOR IN VIVO RETINAL IMAGING

We integrated the LSOR-PAM with a spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT).26 The reasons to combine LSOR-PAM with SD-OCT are twofold. First, we can achieve multimodal imaging from a single scan and the two imaging modalities are intrinsically registered. Second, in retinal imaging in vivo, we can use SD-OCT as an alignment tool to guide PA imaging to minimize the discomfort caused by visible light illumination in PAOM.5

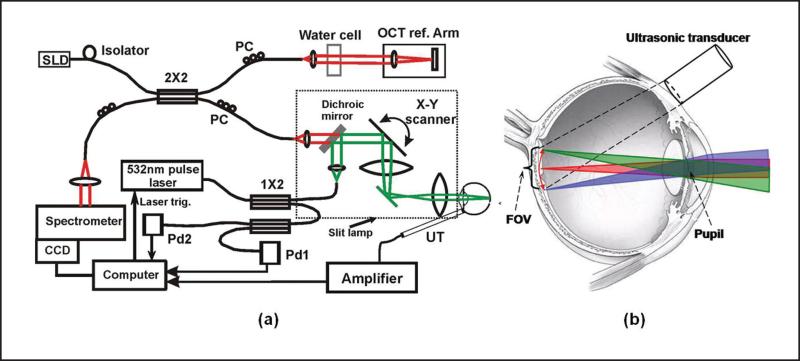

Figure 6a shows a schematic of the OCT-guided PAOM. The illumination source was a frequency-doubled Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (532 nm; 10 μJ/pulse; 2-ns pulse duration; 30-kHz pulse repetition rate). The output laser light was coupled into a 2 × 2 single-mode optical fiber beam splitter. The output laser light from one output arm of the beam splitter was collimated and combined with the OCT light beam in the sample arm by a dichroic mirror. The other output arm of the fiber beam splitter was connected to a multimode fiber beam splitter, the outputs of which were connected to two photodiodes, respectively. To ensure ocular laser safety, the PAOM laser pulse energy was set below 40 nJ/pulse. A detailed derivation of the conformance to the ANSI laser safety standard33 has been published.5,29

Figure 6.

Experimental system of the optical coherence tomography (OCT)-guided photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy (PAOM). (a) Schematic of the OCT-guided PAOM. (b) Illustration of the optical beam delivery to the retina and the position of the ultrasonic transducer. The light delivery systems were built on a slit-lamp biomicroscope. The two imaging subsystems are synchronized by the PAOM laser pulses detected by photodiode Pd1. CCD = charge coupled device; SLD = superluminescent diode; PC = polarization controller; Pd = photodiode; FOV = field of view; UT = ultrasonic transducer. (Reprinted with permission from Jiao SL, Jiang MS, Hu JM, et al. Photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy for in vivo retinal imaging. Opt Express. 2010;18:3967-3972).

The induced PA waves from the retina were detected by a custom-built needle ultrasonic transducer (30 MHz; bandwidth: 50%; active element diameter: 1 mm), which was placed in contact with the eyelid coupled by ultrasound gel (Fig. 6b). The detected PA signals were first amplified by 80 dB, then digitized and stored by a digitizer at a sampling rate of 100 MS/s. The energy of each laser pulse was also recorded by one of the photodiodes (Pd1) to compensate for the pulse energy instability. No signal averaging was used. The axial resolution of the PAOM was independently quantified to be 23 μm and the lateral resolution was comparable to that of the OCT subsystem (differed only by the ratio of the two optical wavelengths between PAOM and OCT).

The fiber-based SD-OCT subsystem is similar to that reported in previous publications.34 The light source has a center wavelength of 870 nm and a full-width half-maximum bandwidth of 100 nm. The exposure time of the line scan charge coupled device (CCD) camera in the spectrometer was set to 36 μs, which can acquire OCT images with a line rate of 24 kHz. The measured sensitivity was better than 95 dB. The calibrated depth resolution was 4 μm in tissue and the lateral resolution was estimated to be 20 μm. The combined PAOM and OCT light beams were scanned by an x-y galvanometer and delivered to the eye through an achromatic relay lens (f = 60 mm) and an objective lens (f = 14 mm).

To ensure automatic registration of the two imaging modalities as previously described,5,35 the PAOM and OCT subsystems were synchronized by the sampling clock of the analogue output board, which triggers both the PAOM laser and the image acquisition board for the CCD camera in the OCT spectrometer and controls the galvanometer scanner. The PAOM data acquisition was triggered by one of the photodiodes (Pd2) to avoid laser jittering. In both PAOM and OCT, the A-line rate was 24 kHz. For B-scan images consisting of 256 A-lines, the B-scan frame rate was 93 Hz. The simultaneous acquisition of the volumetric PAOM and OCT images consisting of 256 B-scans took 2.7 seconds.

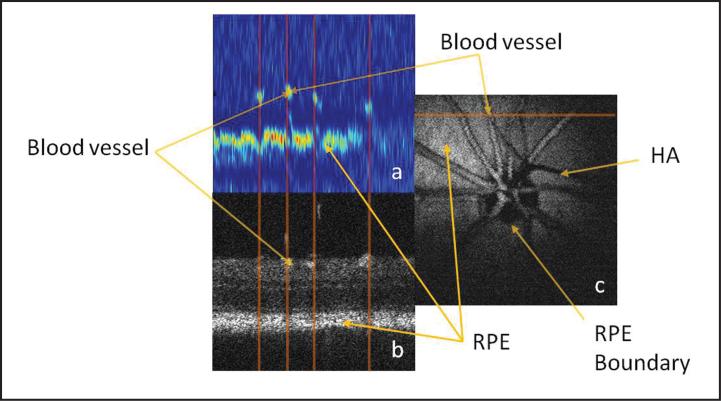

Figure 7 shows the simultaneously acquired PAOM (Fig. 7a) and OCT (Fig. 7b) B-scan images of the left eye of a rat at the position marked in Figure 7c. As clearly seen in the PAOM B-scan, the blood vessels appear as clusters of high-amplitude PA signals. Beneath the blood vessels, the continuous line of high PA amplitude is the RPE layer. The vertical lines mark the corresponding positions of the recognized vessels, which show the automatic registration of the two modalities. Figures 7a and 7b demonstrate the contrast mechanism of PAOM—the stronger the optical absorption, the stronger the generated ultrasonic signals. We can see that the hemoglobin in the blood vessels and the melanin in the RPE cells are strong absorbers of the illuminating light, whereas other retinal tissues have very low optical absorption. This difference in optical absorption provides the foundation of functional and anatomical imaging of the blood vessels and the RPE.

Figure 7.

Comparison of OCT and photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy (PAOM) images acquired simultaneously in vivo. (a) PAOM b-scan image in pseudocolors; (b) OCT b-scan image; (c) maximal amplitude projection image of the PAOM dataset. bar: 100 μm. HA = hyaloid artery; RPe = retinal pigment epithelium. (Reprinted with permission from Jiao SL, Jiang MS, Hu JM, et al. Photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy for in vivo retinal imaging. Opt Express. 2010;18:3967-3972).

Figure 7c shows the MAP of the PA dataset. The circular boundary of RPE at the optic disc can be clearly observed. We can find that inside the optic disc only the blood vessels absorb the illuminating light; thus, the optic disc appears dark except for the blood vessels. The shadow marked hyaloid artery in the MAP image is cast by the hyaloid artery remnant.34 The contrast-to-background ratio in Figure 7c is 23 dB.

It is important to note that in Figure 7a the depth resolution of the current PAOM system is sufficient to resolve the retinal blood vessels from the RPE in the depth direction. This resolving capability guarantees no interference between the blood vessels and the RPE when quantitative absorption is calculated from the images, which is critical for calculating the blood vessel sO2 from the PAOM image.

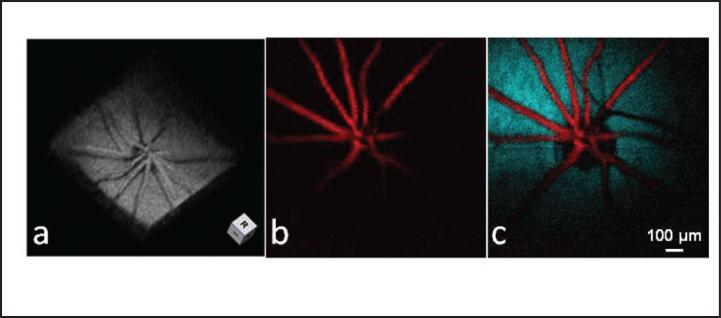

Figure 8 demonstrates the volumetric imaging capability of PAOM. The shadows on the RPE are created by blood vessels blocking the illuminating laser light. Moreover, we developed an algorithm to automatically segment the RPE layer and the retinal vessels. Figure 8b shows the MAP image of the segmented blood vessels, and Figure 8 shows the overlaid MAP image of the segmented retinal vessel onto the segmented RPE, where the vessels are pseudo-colored in red and the RPE is pseudo-colored in blue.

Figure 8.

Volumetric visualization and segmentation of photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy (PAOM) image. (a) Three-dimensional rendering showing the imaged retinal structure by PAOM. (b) Segmented PAOM images of the retinal blood vessels. (c) Pseudo-colored PAOM images of the retinal vessels and RPe. (Reprinted with permission from Jiao SL, Jiang MS, Hu JM, et al. Photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy for in vivo retinal imaging. Opt Express. 2010;18:3967-3972).

PROSPECTS OF PAOM

In this section, we provide our thoughts on the future directions of technological development of PAOM.

Multimodal Retinal Imaging

As a result of its compatibility, PAOM can be integrated seamlessly not only with SD-OCT, but also with other ophthalmic imaging modalities. By detecting the reflected illuminating light in PAOM, we can achieve the function of cSLO27 simultaneously. There is no penalty for laser safety because the reflected photons will be otherwise discarded. Furthermore, PAOM can also be integrated with autofluorescence imaging, yet still share the same excitation light source.36 Such multimodal imaging can be particularly useful in studying the roles of the two key molecules, melanin (through optical absorption) and lipofuscin (through autofluorescence), during the development of age-related macular degeneration.

Metabolic Study of Retina

PAM has long been used to study the sO2 in microvasculature.8,13,15,29 We anticipate that PAOM can measure the sO2 in retinal vessels accurately. Multiwavelength PAOM measurements are necessary for calculating the retinal sO2. In the integrated OCT and PAOM, the blood flow can be measured with OCT; as a result, the metabolic rate of oxygen can be derived based on the measured sO2, blood flow, and vessel diameters.9 Compared with reported retinal oximetry,3,4 PAOM measures optical absorption of hemoglobin directly and is insensitive to the photon propagation paths and RPE melanin concentration; hence, the precision of PAOM is estimated to be higher than reflection-based retinal oximetry. The capability to measure either global or local retinal metabolic rate of oxygen can be important for the study and diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy in its early stage.

Further Improving the Spatial Resolution of PAOM

The lateral resolution of PAOM is determined by the smallest achievable spot size of the illuminating light on the retina. In imaging the eye in vivo, for large pupil diameters, monochromatic aberrations of the eye is the major factor that limits the achievable resolution of retinal images. Although the depth resolution of PAOM could be improved by increasing the bandwidth of the ultrasonic detecting system, the lateral resolution of PAOM is still limited by the optics. One possible approach for correcting the ocular aberrations to decrease the spot size of the illuminating light on the retina, and therefore improve the lateral resolution of PAOM, is to use adaptive optics. Adaptive optics has been applied to ophthalmic imaging with great success, making it possible to image single photoreceptors. Adaptive optics has also been successfully integrated in OCT and SLO.

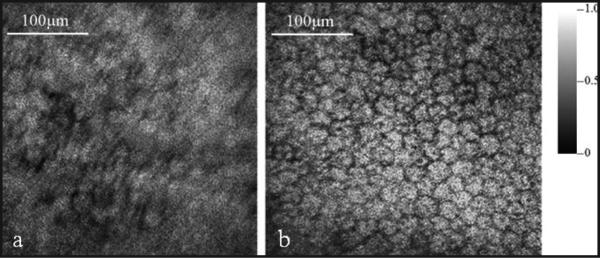

A feasibility study was conducted on the integration of adaptive optics with PAM for ex vivo imaging of ocular tissues,37 which is a technical preparation for the ultimate adaptive optics–PAOM for in vivo retinal imaging. The goal of the study was to correct the aberrations of the optical system for delivering the illuminating light to the sample. A compact close-loop adaptive optics system was integrated into a LSOR-PAM. The adaptive optics system consisted of a real-time Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor operating at 15 Hz and a 141-element MEMS-based deformable mirror.

We imaged the exposed RPE of an excised pig eye. The acquired PAM images without and with adaptive optics correction are shown in Figures 9a and 9b, respectively. The MAP images consist of 256 × 256 pixels covering an area of 0.4 mm × 0.4 mm. From the images we can see significant image resolution improvement with adaptive optics compared with the image without adaptive optics. In the image with adaptive optics single RPE cells are well resolved, whereas in the image without adaptive optics the RPE cells are barely recognizable.

Figure 9.

Maximal amplitude projection of the photoacoustic microscopy images of the retinal pigment epithelium of the pig eye: (a) without adaptive optics and (b) with adaptive optics. (Reprinted with permission from Jiang MS, Zhang XY, Puliafito CP, et al. Adaptive optics photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Express. 2010;18:21770-21776).

Longitudinal Laser Safety Evaluation

Before PAOM can be applied to patient imaging, a thorough evaluation of the laser safety is necessary. Although we have designed the system based on the guidance of ANSI laser safety regulations, monitoring the long-term effect is still necessary.

CONCLUSION

PAOM has been successfully demonstrated in imaging the retina in vivo; however, it is still in its very early stages of development. Tremendous work will need to be done before it can benefit the millions of patients with blinding diseases. Although challenging, the new imaging contrast offered by PAOM may provide new exciting opportunities for the research and clinical diagnosis of major retinal diseases.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grant number NIH 7R21EB008800-02 and the Coulter Translational Award (SJ), and grant number NIH 1RC4EY021357, JDRF Innovative Award 5-2009-498, and Shaw Scientist Award (HFZ).

Dr. Puliafito receives a royalty payment from Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary as a co-inventor of OCT and is a consultant to Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc. The remaining authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the materials presented herein.

Dr. Puliafito did not participate in the editorial review of this manuscript.

The authors thank their collaborators Drs. Amani Fawzi, Janice Burke, and Dennis Han, as well as their students and post-doctoral fellows at both the University of Southern California and Northwestern University: Minshan Jiang, Dr. Xiangyang Zhang, Dr. Jing Wang, Tan Liu, and Dr. Qing Wei.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ruggeri M, Webbe H, Jiao S, et al. In vivo three-dimensional high-resolution imaging of rodent retina with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1808–1814. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cense B, Chen TC, Park BH, Pierce MC, de Boer JF. In vivo depth-resolved birefringence measurements of the human retinal nerve fiber layer by polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography. Optics Lett. 2002;27:1610–1612. doi: 10.1364/ol.27.001610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris A, Dinn RB, Kagemann L, Rechtman E. A review of methods for human retinal oximetry. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2003;34:152–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardarson SH, Harris A, Karlsson RA, et al. Automatic retinal oximetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5011–5016. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiao SL, Jiang MS, Hu JM, et al. Photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy for in vivo retinal imaging. Opt Express. 2010;18:3967–3972. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.003967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell AG. On the production and reproduction of sound by light. Am J Sci. 1880;20:305–324. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen T. Radiation-induced thermoacoustic soft-tissue imaging. IEEE Trans Sonics Ultrasonics. 1982;29:187–187. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang LV. Multiscale photoacoustic microscopy and computed tomography. Nat Photonics. 2009;3:503–509. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2009.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang LV. Prospects of photoacoustic tomography. Med Phys. 2008;35:5758–5767. doi: 10.1118/1.3013698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ntziachristos V. Going deeper than microscopy: the optical imaging frontier in biology. Nat Methods. 2010;7:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang LV, Wu H. Biomedical Optics Principles and Imaging. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. pp. 283–321. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oraevsky AA, Karabutov AA. Optoacoustic tomography. In: Vo-Dinh T, editor. Biomedical Photonics Handbook. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2003. pp. 3401–3434. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang XD, Pang YJ, Ku G, Xie XY, Stoica G, Wang LHV. Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:803–806. doi: 10.1038/nbt839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maslov K, Stoica G, Wang LHV. In vivo dark-field reflection-mode photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Lett. 2005;30:625–627. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.000625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang HF, Maslov K, Stoica G, Wang LHV. Functional photoacoustic microscopy for high-resolution and noninvasive in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:848–851. doi: 10.1038/nbt1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang HF, Maslov K, Wang LHV. In vivo imaging of subcutaneous structures using functional photoacoustic microscopy. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:797–804. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ermilov SA, Khamapirad T, Conjusteau A, et al. Laser optoacoustic imaging system for detection of breast cancer. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14:024007. doi: 10.1117/1.3086616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang EZ, Laufer JG, Pedley RB, Beard PC. In vivo high-resolution 3D photoacoustic imaging of superficial vascular anatomy. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:1035–1046. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/4/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brecht HP, Su R, Fronheiser M, Ermilov SA, Conjusteau A, Oraevsky AA. Whole-body three-dimensional optoacoustic tomography system for small animals. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14:064007. doi: 10.1117/1.3259361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maslov K, Zhang HF, Hu S, Wang LV. Optical-resolution photo-acoustic microscopy for in vivo imaging of single capillaries. Opt Lett. 2008;33:929–931. doi: 10.1364/ol.33.000929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu S, Maslov K, Wang LHV. Noninvasive label-free imaging of microhemodynamics by optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Express. 2009;17:7688–7693. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.007688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu S, Wang LHV. Photoacoustic imaging and characterization of the microvasculature. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15:011101. doi: 10.1117/1.3281673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ku G, Maslov K, Li L, Wang LHV. Photoacoustic microscopy with 2-microm transverse resolution. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15:021302. doi: 10.1117/1.3339912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang C, Maslov K, Wang LHV. Subwavelength-resolution label-free photoacoustic microscopy of optical absorption in vivo. Opt Lett. 2010;35:3195–3197. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.003195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie ZX, Jiao SL, Zhang HF, Puliafito CA. Laser-scanning optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Lett. 2009;34:1771–1773. doi: 10.1364/ol.34.001771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiao SL, Xie ZX, Zhang HF, Puliafito CA. Simultaneous multimodal imaging with integrated photoacoustic microscopy and optical coherence tomography. Opt Lett. 2009;34:2961–2963. doi: 10.1364/OL.34.002961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang HF, Wang J, Wei Q, Liu T, Jiao SL, Puliafito CA. Collecting back-reflected photons in photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Express. 2010;18:1278–1282. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.001278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de la Zerda A, Paulus YM, Teed R, et al. Photoacoustic ocular imaging. Opt Lett. 2010;35:270–272. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu S, Rao B, Maslov K, Wang LV. Label-free photoacoustic ophthalmic angiography. Opt Lett. 2010;35:1–3. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang HF, Maslov K, Sivaramakrishnan M, Stoica G, Wang LHV. Imaging of hemoglobin oxygen saturation variations in single vessels in vivo using photoacoustic microscopy. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;90:3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sivaramakrishnan M, Maslov K, Zhang HF, Stoica G, Wang LV. Limitations of quantitative photoacoustic measurements of blood oxygenation in small vessels. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:1349–1361. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/5/010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maslov K, Zhang HF, Wang LV. Effects of wavelength-dependent fluence attenuation on the noninvasive photoacoustic imaging of hemoglobin oxygen saturation in subcutaneous vasculature in vivo. Inverse Probl. 2007;23:S113–S122. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American National Standards Institute Inc. American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers ANSI Z136.1-2007. Author; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruggeri M, Webbe H, Jiao SL, et al. In vivo three-dimensional high-resolution imaging of rodent retina with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1808–1814. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiao SL, Xie ZX, Zhang HF, Puliafito CA. Simultaneous multimodal imaging with integrated photoacoustic microscopy and optical coherence tomography. Opt Lett. 2009;34:2961–2963. doi: 10.1364/OL.34.002961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang XY, Jiang MS, Fawzi AA, et al. Simultaneous dual molecular contrasts provided by the absorbed photons in photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Lett. 2010;35:4018–4020. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.004018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang MS, Zhang XY, Puliafito CA, Zhang HF, Jiao SL. Adaptive optics photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Express. 2010;18:21770–21776. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.021770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]