Abstract

• Background and Aims Clonal fragments of the rhizomatous dwarf bamboo Sasa palmata, which widely predominates in temperate regions of Japan, were grown under heterogeneous resource conditions such as gap understoreys or nutrient-patchy grassland. Clonal fragments develop multiple ramets with long rhizomes and appear to be physiologically integrated by the translocation of assimilates. The glasshouse experiment reported here was designed to clarify the mechanisms of physiological integration of nitrogen more precisely.

• Methods To assess how resource conditions influence the amount of nitrogen translocation, and which organ acts as the strongest sink, two experiments were conducted that traced movement of 15N label between interconnected pairs of ramets to compare homogeneous and heterogeneous light and soil nitrogen conditions.

• Key Results The amount of 15N translocated to leaves was between 9 % and 11 % greater in high-N and high-light ramets in the heterogeneous compared with homogeneous treatments. Under heterogeneous soil nitrogen conditions, translocation increased from individual ramets in resource-rich patches to ramets in resource-poor patches, while the reverse was true under heterogeneous light environments, reflecting differences in the positions of leaves that act as the strongest sinks. Neither the mass increments nor the total mass of clonal fragments was significantly affected by heterogeneity of either light or nutrients, possibly because the experimental period was too short for differences to manifest themselves.

• Conclusions This study clearly demonstrated that nitrogen is readily translocated between ramets, particularly under heterogeneous resource conditions. The translocation patterns were governed by functional ‘division of labour’ mechanisms that resulted in net nitrogen movement from understorey sites to gaps, thereby enhancing the carbon acquisition of the whole fragment. Thus, physiological integration may provide benefits for S. palmata when it is growing under heterogeneous conditions in which there are deficits of certain environmental resources.

Keywords: Clonal fragment, dwarf bamboo, Sasa palmata, nitrogen, physiological integration, gap, forest understorey, soil nitrogen heterogeneity, heterogeneous light environment

INTRODUCTION

In clonal plants, physiological integration between connected ramets (see Pitelka and Ashmun, 1985) increases net growth and survivorship significantly more under heterogeneous than under homogeneous resource conditions (Hartnett and Bazzaz, 1983; Pitelka and Ashmun, 1985; Stuefer et al., 1994; Wijiesinghe and Handel, 1994; Saitoh et al., 2002; Sergio and Rubén, 2005). One possible reason for this is that clonal plants may be able to optimize the efficiency of their resource utilization by translocating resources along rhizome systems from more favourably placed ramets to ramets in less favourable micro-environments. Another possible reason is that the resource acquisition of entire clonal fragments could be increased by improving the photosynthetic capacity or resouce uptake-capacity in heterogeneous environments (i.e. division of labour or foraging behavior could be beneficial) (Hartnett and Bazzaz, 1983; Friedman and Alpert, 1991; Wijesinghe and Handel, 1994; Hutchings and Wijesinghe, 1997; Lötscher and Hay, 1997; Wijesinghe and Whigham, 2001; Sergio and Rubén, 2005).

Several studies have quantified the translocation of resources (i.e. nutrients) between individual ramets under heterogeneous resource environments, using the stable isotope 15N (Alpert, 1996; Lötshcher and Hay, 1997). However, little is known about which organs (i.e. leaves, stems or roots) are the strongest sinks and sources within individual ramets under such conditions (Sergio and Rubén, 2005). To clarify the mechanisms of physiological integration more precisely, it is necessary to investigate the relative importance of the organs' functioning as sinks of nutrients.

Dwarf bamboos (Sasa spp.) are rhizomatous, have higher grass morphology, and are perennial clonal plants widely distributed in cool temperate regions of Japan (Usui, 1961; Suzuki, 1978). They frequently predominate in grassland, forest understorey, pasture and riverbank habitats, in which environmental resource conditions are usually heterogeneous. For example, in temperate forests, the frequent creation of light gaps of various sizes (as shown by, for example, Yamamoto, 2000) results in spatially heterogeneous light and soil nutrient availability (Lechowicz and Bell, 1991; Seiwa and Kikuzawa, 1996; Denslow et al., 1998). In pastures and grasslands, spatial variations in light or soil nutrient availability have also been found at various scales (Turkington and Harper, 1979; Silvertown, 1981; Turkington et al., 1991). Their heterogeneity is at a finer scale than individual sizes of clonal fragment of dwarf bamboos. In temperate forests of Japan, individual clonal fragments of Sasa palmata, frequently grow under heterogeneous light conditions from light gaps to shaded forest understoreys, by expanding long rhizomes (length 5·5–8·5 m) connecting many above-ground culms (stems) (Saitoh et al., 2000; T. Saitoh and K. Seiwa, unpubl. res.). Furthermore, an experimental study in a field with abundant light (Saitoh et al., 2002), revealed that when ramets within clonal fragments of S. palmata are subjected to highly contrasting levels of shade [1 % ambient photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD)] the reduction in growth of the shaded ramets was compensated by the translocation of assimilates to them from illuminated ramets. These results indicate that S. palmata benefits from physiological integration when growing in spatially heterogeneous habitats such as forest understoreys or grassland. To test this hypothesis in Sasa species, it is necessary to determine whether resources are really translocated among ramets along their rhizome system, and whether the amount of nitrogen (N) moved between ramets within clonal fragments is greater when resources are heterogeneous than when they are homogeneous.

In this study, the translocation of resources along rhizome systems was investigated in detailed stable isotope (15N)-labelling experiments in a glasshouse, in which rhizomatous, clonal fragments of S. palmata were subjected to either homogeneous or spatially heterogeneous environments. The following three questions were addressed: (1) Does translocation of nitrogen in clonal fragments increase when resources are heterogeneous rather than homogeneous? (2) If so, which organs mostly clearly function as sinks of nitrogen? (3) Do the clonal fragments as a whole benefit from this clonal integration when resources are heterogeneous?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant culture

The experiments were carried out in a glasshouse at the Integrated Field Sciences Center of Tohoku University in Naruko Miyagi prefecture, northern Japan (38 °45′N, 140 °45′E; approx. 190 m a.s.l.). For the experiments, 30 clonal fragments of Sasa palmata were carefully excavated from a natural population in an open area at the Integrated Field Sciences Center in May 1997. Each clonal fragment included a pair of ramets of very similar sizes which were located on the opposite ends of a rhizome (approx. 1 m long). For each clonal fragment, two ramets were planted separately in two adjacent plastic trays (58 × 18 cm, 20 cm in depth) filled with a 1:2 mixture of sand and vermiculite. Twelve clonal fragments were used for expt 1 in 1997. The rest of the clonal fragments were temporarily planted in wet soil for a year and transplanted in experimental trays in late May 1998 for expt 2. In both experiments, all clonal fragments were watered regularly with tap water. After approx. 1 month of pre-cultivation, 12 and 14 clonal fragments in which new shoots emerged from dormant buds at the base of each ramet were selected for expts 1 and 2, respectively. The remaining four clonal fragments were not used. The PPFD inside the glasshouse, referred to as ‘open-conditions’ was equivalent to approx. 50 % of full daylight outside the glasshouse. Over the experimental period (May–August), the maximum/minimum temperatures in the glasshouse were 38·5/12·5 °C and 40·5/13 °C in 1997 and 1998, respectively.

Experiment 1 (effects of soil nitrogen heterogeneity)

To test whether clonal fragments translocate more nitrogen in heterogeneous than in homogeneous nitrogen environments, two contrasting treatments were applied. In the homogeneous nitrogen treatments, one ramet of each clonal fragment was given a high level of 14N, while the other was given a high level of 15N. In the heterogeneous nitrogen treatments, one ramet of each clonal fragment was given a low level of 14N, while the other was given a high level of 15N. During the experimental period, high and low levels of N were applied, i.e. 0·5 g N and 0·05 g N [in the form of (NH4)2SO4] per ramet, respectively. Each treatment was replicated six times. In both of these treatments, both ramets of each clonal fragment were exposed to high-light, open conditions in the glasshouse.

Experiment 2 (effects of light heterogeneity)

To test whether more nitrogen is translocated between ramets from those grown in low-light conditions to those grown in high-light conditions in heterogeneous rather than in homogeneous light conditions, two contrasting treatments were applied. In the homogeneous light treatments, both ramets were exposed to unshaded, open-conditions in the glasshouse. In each clonal fragment, one ramet was given 14N while the other was given 15N. This treatment was replicated five times. In the heterogeneous light treatments, one ramet of each clonal fragment was given 14N under unshaded open-conditions, whereas the other was given 15N under low light, shaded conditions (approx. 10 % of ambient PPFD). Shading was imposed by placing small shade cages covered with black cloth above the trays. This treatment was replicated nine times. Application of N, in the form of (NH4)2SO4, supplied 0·5 g N per ramet during the experimental period.

15N labelling and harvests

15N solution was applied from the beginning of the experiments: on 20 June 1997 and 29 June 1998 in expts 1 and 2, respectively. In both experiments, (15NH4)2SO4 (30 atom% 15N) solution was applied to the soil around the ramets in the high 15N sides. All the ramets within clonal fragments were irrigated every 3–4 d with nutrient solution of low or high N concentration containing ample supply of other essential macro-nutrients (P, K, S, Ca, Fe and Mg). A nutrient solution containing all essential micro-nutrients (0·8 mmol Zn, 0·8 mmol Cu, 1·5 mmol Mn, 1·9 mmol B, and 0·3 mmol Mo per tray) was applied before each experiment. In the following text, the 15N-labelled ramet of each clonal fragment is referred to as a labelled-ramet, while the other is referred to as an unlabelled-ramet.

In both experiments, the clonal fragments were grown for 61 d between June and August which is the leaf-emerging period of S. palmata. At the end of both experiments, rhizomes were cut at the mid-point of the two ramets of each clonal fragment, and each ramet (together with the associated fine roots and rhizomes) was harvested. The leaves, culms (stem), rhizomes and roots of each ramet were separated into three components: current growing parts, older parts (>1 year old) and roots. Each component was dried to constant mass. Total nitrogen (15N + 14N) content (total N), excess atom percentage 15N and dry mass were measured for both the current-year and older parts of each organ (i.e. leaves, culms and rhizomes) and roots in each ramet of each clonal fragment. The amount of 15N movement (AMi), i.e. the amount of 15N translocated from roots of individual labelled-ramets to each of the current-year and older organs and roots of individual unlabelled-ramets, was calculated as follows: AMi (mg) = (Mi—0·365)/(A−0·365) × total Ni where A is applied 15N atom percent (30 atom%) and Mi is the measured excess atom percentage 15N of each part of each organ i. The natural abundance of 15N in the samples was assumed to be 0·365 % (Boutton, 1991). The percentage of 15N movement (%Mi) was defined as the ratio of the total amount of 15N translocated from labelled to unlabelled ramets to the amount of 15N absorbed by the roots of labelled-ramets, calculated as follows: %Mi = AMi/AMfrag where AMfrag is the total amount of 15N absorbed per clonal fragment by the roots of labelled-ramets.

Data analysis

To examine differences in the relative sink strengths of individual ramets, the initial ramet and leaf biomass were compared within clonal fragments and between clonal fragments of the two treatments using one-way ANOVA after a paired t-test in each experiment. There were no significant differences in either initial ramet mass or initial leaf mass between these sets of clonal fragments in either experiment (Table 1 and Fig. 1). In this study, thereafter, differences between the values for these sets of data that developed during the course of the experiments were compared within and between the treatments using the paired t-test.

Table 1.

Results of significance tests for initial biomass before conducting the experiments, dry mass increment, after biomass, total N, amount of 15N and percentage of 15N within and between clonal fragments in Sasa palmata

| Expt 1: effect of soil nitrogen |

Expt 2: effect of light |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

Homo |

Hetero |

All |

Homo |

Hetero |

|||||||||||||||||

| d.f. | t | d.f. | t | d.f. | t | Within pair | Between pairs | d.f. | t | d.f. | t | d.f. | t | Within pair | Between pairs | |||||||

| Initial biomass | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leaf | 8 | 0·05 | 3 | 0·62 | 4 | −0·91 | 10 | −0·10 | 3 | −0·01 | 6 | −0·11 | ||||||||||

| Ramet | 11 | 0·12 | 5 | 0·65 | 5 | −0·25 | 13 | −0·67 | 4 | −0·89 | 8 | −0·29 | ||||||||||

| Mass increment | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leaf | 11 | −0·30 | 5 | −1·13 | 5 | 0·45 | 13 | −2·14 | † | 4 | 0·15 | 8 | −2·74 | * | † | |||||||

| Ramet | 11 | −0·05 | 5 | −0·67 | 5 | 1·30 | 13 | −1·86 | † | 4 | −0·65 | 8 | −1·75 | |||||||||

| After biomass | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leaf | 11 | −0·28 | 5 | −0·52 | 5 | 0·38 | 13 | −2·01 | † | 4 | 0·13 | 8 | −2·54 | * | ||||||||

| Ramet | 11 | 0·12 | 5 | −0·60 | 5 | 0·79 | 13 | −1·59 | 4 | −0·84 | 8 | −1·35 | ||||||||||

| Total N | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leaf | 11 | −0·78 | 5 | −1·21 | 5 | 0·54 | 13 | −2·39 | * | 4 | 0·11 | 8 | −3·11 | * | † | |||||||

| Ramet | 11 | −1·11 | 5 | −2·44 | † | 5 | 1·38 | * | 13 | −2·54 | * | 4 | −1·21 | 8 | −2·29 | † | ||||||

| Amount of 15N | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leaf | 11 | 4·53 | *** | 5 | 3·75 | * | 5 | 2·55 | † | 13 | 2·34 | * | 4 | 5·06 | ** | 8 | 1·11 | |||||

| Ramet | 11 | 6·32 | *** | 5 | 3·50 | * | 5 | 5·51 | ** | * | 13 | 5·61 | *** | 4 | 3·47 | * | 8 | 4·18 | ** | |||

| Percentage of 15N | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leaf | 11 | 6·07 | *** | 5 | 12·98 | *** | 5 | 2·60 | * | * | 13 | 3·53 | ** | 4 | 7·55 | ** | 8 | 1·66 | † | |||

| Ramet | 11 | 9·97 | *** | 5 | 8·45 | *** | 5 | 5·72 | ** | − | 13 | 8·29 | *** | 4 | 8·40 | ** | 8 | 5·89 | ** | † | − | |

Differences within and between clonal fragments were tested by one-way ANOVAs after testing for the effects of soil nitrogen (expt 1) or light (expt 2) in all treatments and each treatment by paired t-test. Values are d.f. (degree of freedom), t ratio and its significance for effects (paired t-test or ANOVA: †P < 0·1, *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001).

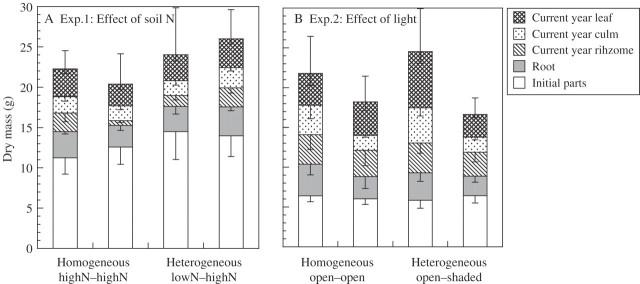

Fig. 1.

Accumulation of dry mass by ramets within clonal fragments in Sasa palmata when heterogeneous and homogeneous resource conditions are compared for the effects of (A) soil nitrogen (expt 1) or (B) light (expt 2). Bars show means; vertical lines show s.e. for total mass of ramets (up) and mass of ramet components within clonal fragments (down).

To test the effects of heterogeneity of the environmental resources light and nitrogen availability on ramet performance, the mass increment, the biomass after experiment, the total N content, the amount of 15N movement and percentage of 15N movement of the sets of ramets and leaves were compared within and between each treatment using paired t-tests. After this analysis, the mean values for these sets of data of clonal fragments were compared within and between treatments using one-way ANOVA in each experiment. To test whether the translocation of 15N between ramets is related to the basipetal or acropetal direction of rhizomes, with respect to the heterogeneity, the effects of the treatments and rhizome direction on the amount of 15N movement in leaves were analysed by two-way ANOVA in each experiment. Statistical tests were performed with the JMP statistical program (SAS Institute, 1995). Data were square-root transformed to meet the assumptions of the normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk's test) where necessary.

RESULTS

Heterogeneity of soil nitrogen (expt 1)

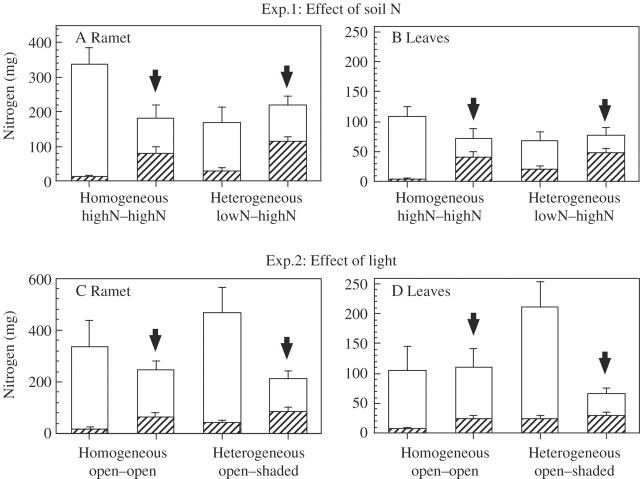

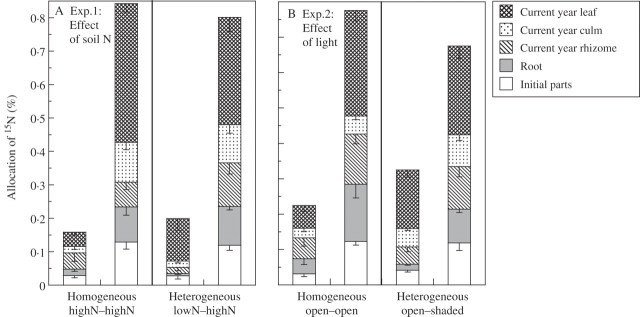

Neither the mass increment and the after biomass of ramets (i.e. leaves + culms + rhizomes) and leaves nor the total N content of the leaves significantly differed within and between clonal fragments (Table 1 and Fig. 2). However, the percentage of 15N movement from the 15N pool of labelled-ramets to newly emerging leaves of unlabelled-ramets were significantly higher in the heterogeneous than in the homogeneous soil N treatment (Table 1 and Fig. 2B). The percentage of 15N in the leaves of unlabelled-ramets was greater in the heterogeneous soil N (13 %) than the homogeneous soil N treatment (4 %) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2.

Total N content (open bars) and amount of 15N (shaded bars) per (A and C) ramet and per (B and D) current-year leaves in Sasa palmata when heterogeneous and homogeneous resource conditions are compared for the effects of (A and B) soil nitrogen (expt 1) or (C and D) light (expt 2). 15N was applied to the soil around the ramets indicated by arrows. See Table 1 for results of significance tests.

Fig. 3.

Partitioning of 15N among ramet components within clonal fragments in Sasa palmata on comparison of heterogeneous and homogeneous resource conditions for the effects of (A) soil nitrogen (expt 1) or (B) light (expt 2).The amount of 15N applied to the soil around the ramets is shown on the vertical axis. Downward error bars show s.e. for ramet components within clonal fragments. See Table 1 for results of significance tests.

At harvest, the mean biomass of individual clonal fragments did not differ significantly between the two treatments (Table 1). However, the amount of total absorption of 15N per ramet (i.e. leaves + culms + rhizomes + roots) was significantly greater when soil N was distributed heterogeneously than when it was homogeneous (Table 1). Total N content per ramet differed significantly between ramets in homogeneous soil N conditions (Table 1), and was highest in unlabelled-ramets in the homogeneous treatment (Fig. 2A), probably because the corresponding clonal fragments had higher N contents at the start of the experiment.

The amount of 15N that moved to leaves was affected by environmental resource heterogeneity, but not by the direction of the movement (acropetal or basipetal) along the rhizome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Leaf 15N of unlabelled ramet and results of significance tests for direction of nitrogen translocation in Sasa palmata

| Acropetal |

Basipetal |

Treatment |

Rhizome direction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf 15N (mg) | n | Leaf 15N (mg) | n | F | P | F | P | |

| Expt 1: the effect of soil nitrogen | ||||||||

| Heterogeneous | 20·9 ± 17·5 | 2 | 18·6 ± 4·8 | 4 | 8·72 | * | 0·02 | NS |

| Homogeneous | 4·9 | 1 | 3·3 ± 1·4 | 5 | ||||

| Expt 2: the effect of light | ||||||||

| Heterogeneous | 13·5 ± 4·4 | 4 | 28·2 ± 9·3 | 5 | 5·79 | * | 1·27 | NS |

| Homogeneous | 5·5 ± 3·7 | 2 | 6·6 ± 3·6 | 3 | ||||

The effects of treatment and rhizome direction (acropetal or basipetal) tested by two-way ANOVAs. Values are mean ± s.e., F ratio and its significance for effects (ANOVA: *P<0·05; NS, not significant).

Heterogeneity of light (expt 2)

The mass increment and after biomass of leaves and the total N content of leaves were significantly higher, and total N content of ramets (i.e. leaves + culms + rhizomes + roots) were marginally higher in the open ramets than the shaded ramets in the heterogeneous light treatment (Table 1 and Figs 1B and 2C, D). However, the percentage of the 15N pool of labelled-ramets that moved to unlabelled-ramets and newly emerging leaves were marginally higher in the heterogeneous than in the homogeneous light treatment (Table 1 and Fig. 2C, D). The percentage of 15N movement in the leaves of unlabelled-ramets was greater in the heterogeneous (17 %) than in the homogeneous light treatment (6 %) (Fig. 3B).

The mean biomass of individual clonal fragments did not differ significantly between the two treatments (Table 1). However, the percentage of 15N movement per ramet (i.e. leaves + culms + rhizomes + roots) was marginally greater in heterogeneous than in homogeneous light conditions (Table 1 and Fig. 3B). In the heterogeneous light conditions, the total N content per leaf differed marginally between ramets, and was higher in exposed ramets compared with shaded ramets (Table 1 and Fig. 2D).

The amount of 15N that moved to leaves was affected by environmental light heterogeneity but not by the direction of the movement (acropetal or basipetal) along the rhizome (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Resource heterogeneity and nitrogen translocation

This stable isotope 15N-labelling study clearly revealed that the dwarf bamboo Sasa palmata readily translocates nitrogen between ramets along the rhizome system, particularly under heterogeneous environmental resource conditions. Although these results are in accordance with previous studies of several plant species of other taxa (Jonsdottir and Callaghan, 1990; Alpert, 1996; Derner and Briske, 1998) this is the first stable isotope study, as far as is known, to demonstrate the physiological integration between ramets in woody and higher grass morphology clonal plants (bamboo, dwarf bamboo). Furthermore, this study revealed that translocation patterns of nitrogen were especially distributed to the leaves, which presumably are acting as the strongest sinks. There were no significant differences in either the mass increment and the total mass of clonal fragments grown in heterogeneous (light or nutrient) conditions and those grown in homogenous conditions in both the experiments, although the total amounts of exposed resources available were lower in the former than the latter, perhaps because the experimental period ran for so little time. Therefore, it was not possible to conclude that a clonal fragment of S. palmata benefits from physiological integration of nitrogen.

Under heterogeneous light conditions, the results of translocated nitrogen from shaded ramets to exposed leaves within individual clonal fragments suggests that nitrogen translocation between ramets was prompted by the transpiration of newly emerged leaves of light-exposed ramets acting as strong nitrogen sinks (Marshall, 1990). Such a nitrogen translocation pattern would have strongly contributed to optimization of net photosynthesis and maximization of carbon acquisition, not only for open ramets but also for entire fragments, since higher nitrogen concentrations per unit leaf area is beneficial in increasing photosynthetic ability, particularly under abundant light conditions (Hirose and Werger, 1994; Sergio and Rubén, 2005), whereas shaded ramets had a lower nitrogen content by exporting nitrogen to the open-ramet. Furthermore, when clonal fragments were exposed to heterogeneous light conditions in previous studies of S. palmata (Saitoh et al., 2002), ramets under open conditions allocated more biomass to their leaves than shaded ones, irrespective of rhizome connection, and the individual leaf had modified morphological plasticity independently of such physiological integration. Thus, the results of this study, together with previous findings, may indicate a division of labour for carbon acquisition in S. palmata clonal fragments (Hutchings and Wijesinghe, 1997; Allison et al., 2005).

Under heterogeneous soil nitrogen environments, S. palmata translocated nitrogen from high-N ramets to low-N leaves within individual clonal fragments. Marshall (1990) showed that the increasing sink strength of emerging or elongating leaves could prompt the translocation of mineral nutrients. The present results also suggest that the mass of the emerging new leaves was not decreased by translocation of nitrogen between ramets, even in the low-N ramets, since the low-N ramet would act as a strong nitrogen sink. Therefore, such physiological integration between ramets may have the potential to reduce the loss of photosynthetic ability of both ends of a ramet, even in the micro-environment of nitrogen shortage under abundant light conditions (Sergio and Rubén, 2005).

The direction of resource translocation within individual clonal fragments differed between those subjected to soil nitrogen heterogeneity and those subjected to light heterogeneity. In heterogeneous soil nitrogen conditions, translocation of nitrogen increased from individual ramets in resource-rich patches to ramets in resource-poor patches, while the reverse was true in heterogeneous light conditions. This difference would be approximately caused by differences in the positions of sinks along rhizome systems, and ultimately governed by the selective pressure for clonal fragments to allocate nitrogen within and among ramets in such a way that their overall carbon acquisition parameters are optimized.

Implications for natural habitats

In both temperate and tropical forests, light intensities are higher in light gaps but the availability of water and/or nutrients tends to be lower than in understoreys (Stuefer et al., 1994; Seiwa and Kikuzawa, 1996), because of the rapid decomposition of the large mass of litter from the fallen trees that created the gaps, although the soil concentrations of nutrients return to background levels within a year from the treefall in tropical forests (Denslow et al., 1998). In temperate forests of Japan, single clonal fragments of S. palmata often grow under heterogeneous light conditions, extending from gap to forest understorey, with long (5·5–8·5 m) rhizomes connecting the various above-ground culms (ramets) (T. Saitoh and K. Seiwa, unpubl. res.). Sasa palmata may therefore depend on physiological integration of assimilates to persist in the heterogeneous resource environments characteristic of the understorey (Saitoh et al., 2002). In addition, this study confirmed that nitrogen is translocated in S. palmata from ramets growing under the characteristic low-light and high soil N conditions of forest understories to ramets growing under the characteristic high-light and low soil N conditions of gaps. It is inferred from these observations that clonal fragments of S. palmata translocate different resources (i.e. mineral nutrients and assimilates) bidirectionally, as previously described in herbaceous clonal species (Alpert and Mooney, 1986; Stuefer et al., 1994, 1996; Shumway, 1995). This is one of the mechanisms whereby populations of S. palmata persist vegetatively, and subsequently predominate in heterogeneous resource and limited light environments in the forest.

This study was based on glasshouse experiments in which the clonal fragments of S. palmata were planted in conditions where two resources (light and nitrogen) were separately varied while all other variables were kept constant. Under field conditions, the availabilities of two or more resources are often negatively correlated in space (Stuefer, 1994; Alpert and Mooney, 1996). Thus, further experimental studies are needed to assess responses in the field to such complex resource heterogeneities. This glasshouse experiment demonstrated that nitrogen is translocated from labelled-ramets to neighbouring leaves up to at least 1 m away. Further study is needed to establish whether translocation occurs over longer distances in the field.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Akasaka Shigetoshi and Imai Akane for assistance with fieldwork and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that greatly improved the manuscript. We are grateful to the following for helpful discussions and comments: Dr Saigusa Masahiko, Dr Ito Toyoaki, Dr Makita Akifumi, Dr Suyama Yoshihisa, Dr Sugita Hisashi, Imai Akane, Dr Ueno Naoto, Dr Tomita Mizuki, Dr Kimura Megumi Dr Kabeya Daisuke and Miwa Yoshiko. This study was supported by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute in Japan (Japanese National Institution of Forest).

LITERATURE CITED

- Allison P, Chad H, Kristin R, Deborah EG. 2005. Do physiological integration and soil heterogeneity influence the clonal growth and foraging of Schoenoplectus pungens? Plant Ecology 181: 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Alpert P. 1996. Nutrient sharing in natural clonal fragments of Fragaria chiloensis. Journal of Ecology 84: 395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Alpert P, Mooney HA. 1986. Resource sharing among ramets in the clonal herb, Fragaria chiloensis. Oecologia 70: 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert P, Mooney HA. 1996. Resource heterogeneity generated by shrubs and topography on coastal sand dunes. Vegetatio 122: 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Boutton TW. 1991. Stable carbon isotope ratios of natural material. I. Sample preparation and mass spectrometric analysis. In: Coleman DC, Fry B, eds. Carbon isotope techniques. New York, NY: Academic Press, 155–171.

- Denslow JS, Ellison AM, Sanford RE. 1998. Treefall gap size effects on above- and below-ground processes in a tropical wet forest. Journal of Ecology 86: 597–609. [Google Scholar]

- Derner JD, Briske DD. 1998. An isotopic (15N) assessment of intraclonal regulation in C4 perennial grasses: ramet interdependence, independence or both? Journal of Ecology 86: 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Alpert P. 1991. Reciprocal transport between ramets increases growth of Fragaria chiloensis when light and nitrogen occur in separate patches but only if patches are rich. Oecologia 86: 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett DC, Bazzaz FA. 1983. Physiological integration among intraclonal ramets in Solidago canadensis. Ecology 64: 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T, Werger MJA. 1994. Photosynthetic capacity and nitrogen partitioning among species in the canopy of a herbaceous plant community. Oecologia 100: 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings MJ, Wijesinghe DK. 1997. Patchy habitats, division of labour and growth dividends in clonal plants. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 12: 390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsdottir IS, Callaghan TV. 1990. Intraclonal translocation of ammonium and nitrogen in Carex bigelowii Torr. ex Schwein. using 15N and nitrate reductase assays. New Phytologist 114: 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechowicz MJ, Bell G. 1991. The ecology and genetics of fitness in forest plants. II. Microspatial heterogeneity of the edaphic environment. Journal of Ecology 79: 687–696. [Google Scholar]

- Lötscher M, Hay MJM. 1997. Genotypic differences in physiological integration, morphological plasticity and utilization of phosphorus induced by variation in phosphate supply in Trifolium repens. Journal of Ecology 85: 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C. 1990. Source–sink relations of interconnected ramets. In: van Groenendael J, de Kroon H, eds. Clonal growth in plants: regulation and function. The Hague: SPB Academic Publishing, 23–41.

- Pitelka LF, Ashmun JW. 1985. Physiology and integration of ramets in clonal plants. In: Jackson JBC, Buss LW, Cook RE, eds. Population biology and evolution of clonal organisms. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 399–437.

- Saitoh T, Seiwa K, Nishiwaki A, Kanno H, Akasaka S. 2000. Spatial distribution patterns of Sasa palmata in relation to light conditions across gap-understory continuum in a beech (Fagus crenata) forest. Journal of Japanese Forest Society 82: 342–348 [in Japanese]. [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh T, Seiwa K, Nishiwaki A. 2002. Importance of physiological integration of dwarf bamboo to persistence in forest understorey: a field experiment. Journal of Ecology 90: 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- SAS. 1995. JMP user's guide. Version 3 of JMP. Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

- Seiwa K, Kikuzawa K. 1996. Importance of seed size for the establishment of seedlings of five deciduous broad-leaved tree species. Vegetatio 123: 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sergio RR, Rubén R. 2005. Presence of developing ramets of Fragaria vesca L. increases photochemicals in parent ramets. International Journal of Plant Science 166: 795–803. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway S. 1995. Physiological integration among clonal ramets during invasion of disturbance patches in a New England salt marsh. Annals of Botany 76: 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Silvertown JW. 1981. Micro-spatial heterogeneity and seedling demography in species-rich grassland. New Phytologist 88: 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Stuefer JF, During HJ, de Kroon H. 1994. High benefits of clonal integration in two stoloniferous species, in response to heterogeneous light environments. Journal of Ecology 82: 511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Stuefer JF, de Kroon H, During HJ. 1996. Exploitation of environmental heterogeneity by spatial division of labour in a clonal plant. Functional Ecology 10: 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S. 1978. Index to Japanese Bambusaceae. Tokyo: Gakken [in Japanese].

- Turkington R, Harper JL. 1979. The growth, distribution and neighbour relations of Trifolium repens in a permanent pasture. I. Ordination, pattern and contact. Journal of Ecology 67: 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Turkington R, Hamilton RS, Gliddon C. 1991. Within-population variation in localized and integrated responses of Trifolium repens to biotically patchy environments. Oecologia 86: 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui H. 1961. Phytosociological revision of the dominant species of Sasa-type undergrowth: silvicultural application of the researches on Japanese forest vegetation. Special Bulletin of the College of Agriculture, Utsunomiya University 11: 1–35 [in Japanese]. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe DK, Handel ST. 1994. Advantages of clonal growth in heterogeneous habitats: an experiment with Potentilla simplex. Journal of Ecology 82: 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe DK, Whigham DF. 2001. Nutrient foraging in woodland herbs: a comparison of three species of Uvularia (Liliaceae) with contrasting belowground morphologies. American Journal of Botany 88: 1071–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S. 2000. Forest gap dynamics and tree regeneration. Journal of Forest Research 4: 223–229. [Google Scholar]