Abstract

Dynein-mediated pulling forces generated on dynamic microtubule ends at the cortex contribute to cellular positioning processes such as spindle positioning during embryonic cell division and centrosome positioning during fibroblast migration. The details of dynein’s interaction with microtubule ends, and its consequences for positioning processes remain however unclear. We have reconstituted the ‘cortical’ interaction between dynein and dynamic microtubule ends in an in vitro system using microfabricated barriers. We show that barrier-attached dynein captures microtubule ends, inhibits growth, and triggers microtubule catastrophes, thereby controlling microtubule length. The subsequent interaction with shrinking microtubule ends generates pulling forces up to several pN. By combining experiments in microchambers with a theoretical description of aster mechanics, we show that dynein-mediated pulling forces lead to the reliable centering of microtubule asters in simple confining geometries. Our results demonstrate the intrinsic ability of cortical microtubule-dynein interactions to regulate microtubule dynamics and drive positioning processes in living cells.

INTRODUCTION

In cells, the organization of the microtubule (MT) cytoskeleton is often dictated by the activity of MT-nucleating organelles such as the centrosome or the nucleus. For many cellular processes, it is essential that these so-called MT-organizing centers (MTOCs) faithfully position themselves with respect to the confining geometry of the cell. For example, in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos, asymmetric positioning of the mitotic spindle, organized by two MT-nucleating centrosomes (Figure 1A), is necessary for establishment of the anterior-posterior axis (Cowan and Hyman, 2004). In budding and fission yeasts, the spindle and the nucleus need to be properly positioned for faithful localization of the mitotic plane (in the bud neck and in the cell center, respectively) (Carminati and Stearns, 1997; Chang and Nurse, 1996). In migrating fibroblasts the position of the centrosome is implicated in the delivery of membrane vesicles to the leading edge of the cell (Schmoranzer et al., 2003), and in T-cells it reinforces the initial polarity that has been established by the actin cytoskeleton (Stinchcombe et al., 2006). So how do MTOCs sense and control their position in cells of different size and shape? How do they ‘measure’ the distance to the cell periphery and harness the forces needed to adapt their position accordingly?

Figure 1. Cortical dynein captures dynamic MT ends.

(A) End-on MT-dynein contacts during spindle positioning in C. elegans embryos. (B) Schematic view of the reconstituted interaction between dynamic MT ends and ‘cortical’ dynein. (C,D) Spinning disc confocal fluorescence images of MTs interacting with a barrier without (C; Movie S1) and with (D; Movie S2) dynein (using the multilayer). Yellow line indicates the position of the barrier. Scale bar indicates 5 μm. (E,F) MTs growing against barriers coated with 100% dynein without (E; Movie S3) and with (F) use of the multilayer. Scale bars indicate 10 μm. (G) Numbers of straight (stalled) and buckled (growing) MTs observed, and numbers of observed release and catastrophe events for various dynein densities (0% refers to no dynein, Multi refers to the use of a multilayer as in D). See Figure S1 for details on the detection of buckled MTs. (H) Release (straight MTs) and catastrophe (buckled MTs) frequencies for the various conditions. Error bars give the statistical errors based on the number of observed events. For cases with fewer than 6 events only an upper limit corresponding to a 95% confidence interval is shown.

Invariably, MTOC positioning appears to be mediated by the interaction of dynamic MTs with the cell cortex. The dynamics of MTs is characterized by a process termed dynamic instability: MTs alternate between growing and shrinking states that are separated by so-called catastrophe and rescue events (Desai and Mitchison, 1997). It is by now well established that MT growth can lead to the generation of pushing forces (Dogterom et al., 2005; Dogterom and Yurke, 1997) and that MT shrinkage can lead to the generation of pulling forces (Grishchuk et al., 2005; Lombillo et al., 1995). In some cases positioning is achieved by growth-induced MT pushing forces, for example during nuclear positioning in Schizosaccharomyces pombe cells in interphase (Tran et al., 2001). In most cases, however, positioning appears to be driven by dynein-mediated pulling forces generated at the cell cortex (Burakov et al., 2003; Carminati and Stearns, 1997; Desai and Mitchison, 1997; Dujardin and Vallee, 2002; Grill et al., 2001; Koonce et al., 1999; Nguyen-Ngoc et al., 2007; Vallee et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2001). Important questions that thus need to be answered are how dynein at the cortex may be involved in the regulation of MT dynamics and length, how the dynein-MT interaction leads to the generation of cortical pulling forces, and how this may contribute to the correct positioning of MTOCs.

In principle, dynein itself may be responsible for the generation of pulling forces, as dynein is a processive minus-end directed motor (Reck-Peterson et al., 2006) that can pull on a MT-organizing center by moving laterally along the MT lattice, without the need for any direct interaction with the dynamic MT end. This type of ‘lateral’ cortical contact is observed in dividing Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells, where motion of the nucleus into the bud neck is mediated by MTs gliding along the cortex in a dynein-dependent manner (Carminati and Stearns, 1997). However, dynein-MT interactions often appear to be accomplished in a configuration where the MT is facing the cortex ‘end-on’. In this configuration, dynein may act as a linker that allows the transmission of forces generated by shrinking MT ends, similar to what has been reported for other MT-associated end-binding (motor) proteins (Franck et al., 2007; Grissom et al., 2009; Lombillo et al., 1995). End-on contacts appear to drive nuclear motions during the very early and late stages of cell division in budding yeast, (Adames and Cooper, 2000), spindle positioning in the first cell stage C. elegans embryo, (Figure 1A, detail) (Kozlowski et al., 2007; Labbe et al., 2003), and, at least in part, nuclear motions during meiotic prophase in S. pombe (Vogel et al., 2009; Yamamoto et al., 2001).

Here, we show in a series of in vitro experiments that, in an end-on configuration, barrier-attached dynein is able to regulate MT dynamics and to control MT length. We show that the interaction between dynein and shrinking MTs generates pulling forces of several pN. These pulling forces contribute to the precise centering of dynamic MT asters, when confined to simple symmetric microfabricated chambers with dynein attached to their sidewalls. We explain this result by a theoretical description of aster mechanics in the presence of pulling forces. Since cortical end-on MT-dynein interactions automatically tune MT length to the distance between MTOC and cell cortex, we propose that this system provides MTOCs with a reliable mechanisms to both sense and control their position in cells of different size and shape.

RESULTS

Barrier-Attached Dynein Captures Dynamic MT Ends and Controls MT Length

We reconstituted the cortical interaction between dynein and dynamic MT ends in a minimal in vitro system. In our assays, dynamic MT ends interact with a microfabricated barrier coated with a truncated version of S. cerevisiae’s cytoplasmic dynein, which was biotinylated after purification (GST-Dyn331, referred to hereafter as dynein). Previous experiments have shown that this truncated dynein exhibits processive minus-end-directed motility and stalls at a force (4.8 ± 1.0 pN) similar to full length dynein (Gennerich et al., 2007; Reck-Peterson et al., 2006). In our first experiments, fluorescently-labeled MTs grew from surface-attached centrosomes towards gold barriers (Figure 1B). By exploiting gold-specific-chemistry and surface blocking of the non-gold surfaces, dynein was attached specifically to the barriers through a multilayer of biotin-streptavidin linkages (Laan and Dogterom, 2010; Romet-Lemonne et al., 2005) (see also detail Figure 4A).

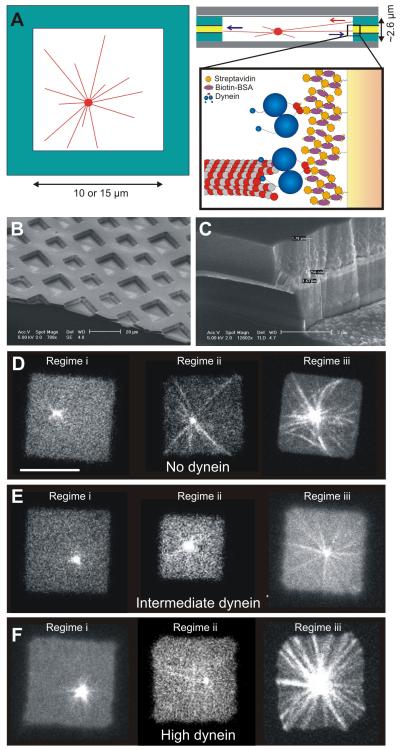

Figure 4. The positioning of MT asters in microfabricated chambers.

(A) Schematic picture of a dynamic MT aster confined in a microfabricated chamber. Detail shows the attachment of dynein molecules via a multilayer of streptavidin and biotin-BSA (roughly to scale). (B) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the microfabricated chambers. (C) SEM image of a sidewall. (D,E,F) Single plane spinning disk confocal fluorescence images for no dynein (D), intermediate dynein amounts (E), and high dynein amounts (F) on the walls. In regime (i), the average MT length is short, in regime (ii) it is similar, and in regime (iii) it is long compared to the chamber size 2d. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. In each regime, asters were followed for 60 - 600 sec with 3 sec time intervals.

We followed individual MTs over time using spinning disk confocal fluorescence microscopy. In the absence of dynein at the barrier, most MTs (91 out of 105) continued to grow and buckled upon reaching the barrier (Figure 1C, Movie S1), while a minority of MTs (14 out of 105) stopped growing and remained straight. Both buckled and straight MTs sometimes switched to a shrinking state (this event is termed a catastrophe). For straight MTs this led to the immediate release from the barrier, while buckled MTs first straightened and then lost contact with the barrier. The release (i.e. catastrophe) frequency for straight MTs was higher than the catastrophe frequency for growing buckled MTs (0.22 ± 0.09 min−1 versus 0.024 ± 0.007 min−1; p-value 6.3*10−5; Figure 1GH) due to the generation of a compressive force, as previously observed (Janson et al., 2003). The catastrophe frequency for buckled MTs was comparable to that of freely growing MTs under the same conditions (0.019 ± 0.006 min−1; p-value 0.26; Figure 1H, Table 1). In the presence of dynein, almost all MTs (60 out of 65) stopped growing after their ends hit the barrier (Figure 1D, Movie S2), whereas only a few were observed to continue to grow and buckle. In contrast to the situation without dynein, MTs remained in a straight conformation for very long times. The frequency at which these MTs were observed to release from the barrier (≈ 0.007min−1; < 0.016 min−1 with 95% confidence for 4 observed events) was much lower than in the absence of dynein (p-value 7.1*10−8; Figure 1GH: Multi). MTs were never observed to make lateral contact with the dynein-coated barrier (total of 20 centrosomes, at an average distance of 9.2 ± 4.2 μm, SD, from the barrier). These experiments show that barrier-attached dynein captures MT ends, stops MT growth, but also prevents MT shrinkage, thereby prolonging the contact time with the barrier, and tuning the MT length to the distance between the centrosome and the barrier.

Table 1. Parameters of MT dynamics for free and gliding MTs.

| n=events M=MTs |

Freely growing from centrosome |

Gliding on dynein (no barrier) |

Gliding on dynein (against barrier) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Vgrowth

(μm/min) |

1.3 +/− 0.4 (M= 38) |

1.4 +/− 0.4 (M=20) |

- |

|

Vshrink

(μm/min) |

7.5 +/− 2.0 (M= 23) |

7.7 +/− 3.7 (M= 16) |

3.4 +/− 0.8 (M=20) |

|

fcat

(1/min) |

0.019 +/− 0.006 (n=11, M=38) |

0.021 +/− 0.006 (n=14, M=20) |

0.75 +/− 0.19 (n=18, M=20) |

|

fres

(1/min) |

<0.103 (95% conf) (n=0, M=38) |

0.67 +/− 0.30 (n=8, M=20) |

- |

In these first experiments we attempted to maximize the surface density of dynein on the barriers by using a multilayer of biotin-streptavidin linkages. To investigate whether a high surface density of dynein molecules was required to trigger the observed effects, we reduced the dynein density on the gold barriers, first by using only a single biotin-streptavidin layer (100% dynein in Figure 1GH), and second by diluting the biotinylated dynein with biotinylated bovine serum albumin (BSA; 10% and 1% dynein in Figure 1GH). At lower dynein densities, we found fewer straight MTs in contact with the barriers and more growing, buckled MTs (Figure 1G). Also, the time MTs spent ‘searching’ for a stable contact at the barrier increased relative to the higher dynein concentration (Supplemental Information). The release frequency of the straight, non-growing MTs at the barriers remained however lower than when no dynein was present (p-values 100%: 6.8*10−4, 10%: 0.0021, 1%: 0.089; Figure 1H). These observations show that dynein molecules do not need to be densely packed to be able to stabilize the MT contact with the barrier.

Barrier-Attached Dynein Regulates MT Dynamics

The dynein-mediated stabilization of MT ends that we observe at the barriers could be due to either the inhibition of MT catastrophes or the stalling of subsequent MT shrinkage. We could sometimes observe how a growing buckled MT, after undergoing a catastrophe and shrinking back to a straight conformation, remained in contact with the barrier for some time (Figure 1E; Movie S3). This suggests that catastrophes are not prevented by the capture of MT ends, but that shrinkage is stalled as soon as the MT is pulled straight between the surface-attached centrosome and the dynein contact point. In fact, the catastrophe frequency of growing buckled MTs at low dynein coverage (1% and 10%) was higher than in the complete absence of dynein (p-values 1%: 0.012, 10%: 0.0033; Figure 1H), suggesting that barrier-attached dynein rather enhances catastrophes (for 100% and Multi, too few buckled MTs and catastrophe events were observed to confirm that the catastrophe frequency was enhanced).

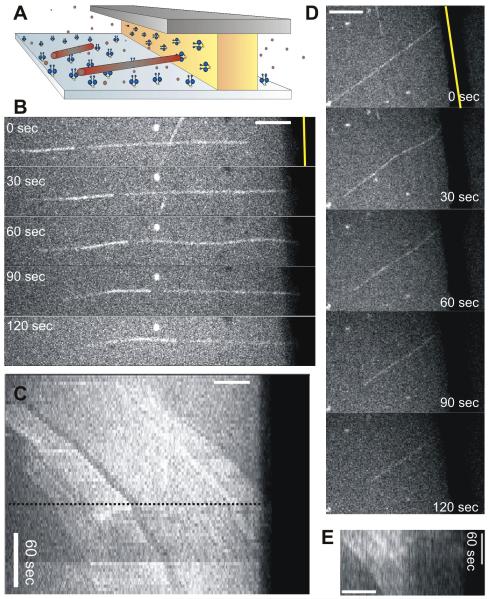

To further test whether barrier-attached dynein prolongs MT contact by preventing catastrophes or by stalling shrinkage, we performed an experiment similar to Figure 1, in which in addition to the barrier, the bottom surface of the sample was coated with dynein molecules. In this case, growing MTs were pulled loose from the centrosome and glided towards the barrier (Figure 2; Movie S4). When these MTs hit the barrier, they quickly underwent a catastrophe (fcat = 0.75 ± 0.19 min−1; Table 1), but the shrinking MT ends stayed in contact with the barrier. The subsequent shrinkage velocity was much slower (3.4 ± 0.8 μm/min, SD) than in the case of centrosome-nucleated MTs shrinking freely under the same conditions (7.5 ± 2.0 μm/min, SD) (p-value 3.1*10−10; Table 1). The shrinkage velocity was also slower than the dynein gliding velocity (7.8 ± 2.1 μm/min, SD), which means that both MT shrinkage and dynein motion were slowed down by the dynein-MT interaction at the barrier. We thus conclude that barrier-attached dynein does not prevent, but rather enhances catastrophes, and slows down (or even stalls, see Figure 1D) subsequent MT shrinkage. To test whether dynein induces catastrophes by a putative depolymerizing activity, we also performed gliding experiments with MTs that were stabilized with GMPCPP, a slowly hydrolysable analogue of GTP. These stabilized MTs stopped moving along the bottom surface when they contacted the barrier, but shrinkage was never observed (Figure S2AB).

Figure 2. Barrier-attached dynein triggers catastrophes and slows down MT shrinkage.

(A) Schematic view of the gliding experiment. (B) MT gliding with its plus-end against a barrier (Movie S4). (C) Kymograph of the same MT. The MT hits the barrier at the dotted line. MT speckles show that the MT undergoes a catastrophe and continues gliding while shrinking. (D) Another gliding MT showing similar behavior. (E) Accompanying kymograph, where only the left half of the MT can be seen due to buckling. Scale bars indicate 5 μm.

It is important to note that the effects on MT dynamics described so far were only observed when dynein molecules were attached to a barrier that faced the dynamic MT end-on. In this configuration, dynein is geometrically enforced to interact with only the very end of the MT while the dynamic MT end stays in perpendicular contact with the barrier. This leads to a coupling between dynein and MT dynamics (see also Discussion). By contrast, no changes in dynamics were observed when dynein was present in solution instead of attached to a barrier (Figure S2CDE). Even a dynein mutant that moves much slower than the MT shrinks (vglide = 0.22 ± 0.16 μm/min, SD) (Cho et al., 2008), had no effect on MT dynamics when present in solution. Similarly, as shown in Table 1, when dynamic MTs were gliding on a dynein-coated surface, no changes in growth velocity, shrinkage velocity, or catastrophe frequency were observed before contact with the barrier was established. In this case, only the rescue frequency was increased. When we performed conventional gliding assays at increasing dynein densities (done separately in the absence of barriers), we observed occasional lower shrinkage velocities, leading to a modest reduction of the average shrinkage velocity (Figure S2FGH). However, the motor gliding velocity was not reduced, and the MT growth velocity was also unaffected. We thus conclude that the enhanced MT catastrophe frequency and reduced motor velocity that we observe are the strict result of the dynein-coated barrier facing the dynamic MT end-on. We further conclude that dynein can only slow down MT shrinkage when it is associated with MT ends.

Barrier-Attached Dynein Generates Pulling Forces at Shrinking MT Ends

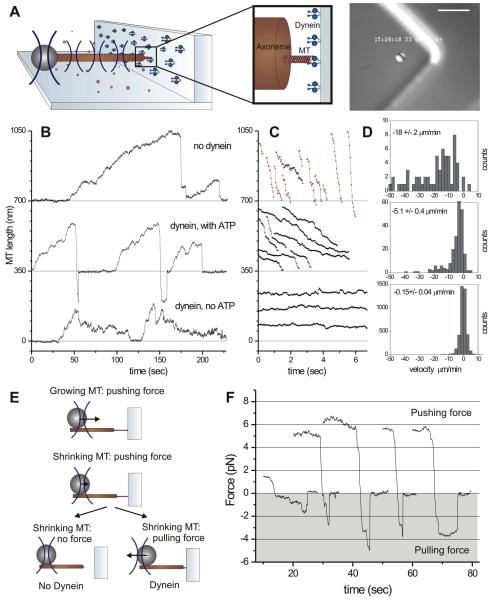

We next used an optical trap set-up to reveal whether pulling forces were indeed generated by the MT-dynein interaction at the barrier. In these experiments, dynein was non-specifically attached to barriers made of photo resist (Supplemental Information). MTs grew from an axoneme-bead-construct, which was positioned in front of a barrier with the help of an optical trap (Figure 3A) (Kerssemakers et al., 2006). Figure 3B shows sequences of MT growth and shrinkage events in the absence (top), and the presence of barrier-attached dynein, with and without the addition of ATP (middle and bottom). In all three cases, when a growing MT reached the barrier, the bead was pushed away until the MT switched to a shrinking state. As the MT shrank, the bead moved back to the center of the trap, after which, in the absence of dynein, contact between the shrinking MT and the barrier was lost until a new MT started growing. However, when dynein and ATP were present, a pulling force was generated that caused the bead to continue to move towards the barrier, beyond the center of the trap (see schematic in Figure 3E). These experiments show that in the presence of ATP, dynein can maintain the connection to a shrinking MT for several seconds, against pulling forces up to ~5 pN (the connection was lost at a mean force of 2.0 ± 1.4 pN, SD; n = 10) (Figure 3F, Table S1). In the absence of ATP, which causes dynein to bind to MTs in a rigor state, no detectable pulling forces were generated (Figure 3B bottom), indicating that motor activity is needed for force generation (Table S1). It is possible, however, that motor activity is only needed to maintain a dynamic connection between the barrier and the shrinking MT, as the work against the applied load (wholly or in part) may be performed by the depolymerizing MTs themselves (Grishchuk et al., 2005; Lombillo et al., 1995; McIntosh et al., 2010).

Figure 3. Barrier-attached dynein pulls on shrinking MT ends.

(A) Schematic view of the optical trap experiment. Detail is roughly drawn to scale. Image shows a DIC snapshot of the experiment. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. (B) Growth and shrinkage of MTs interacting with an uncoated barrier (upper trace), and with a dynein-coated barrier in the presence (middle trace) and absence (lower trace) of ATP. (C) Shrinkage events of the three experiments. Shrinkage intervals with a velocity higher/lower than 10 μm/min (measured over 120 ms) are indicated in red/black. (D) Histograms and average values (± SE) of all 120-ms shrinking velocities (see also Table S1). (E) Schematic of forces experienced by dynamic MT ends. (F) Shrinkage events resulting in the generation of a pulling force (shaded in grey).

In these experiments, we again found that MTs shrank more slowly when pushed against a dynein-coated barrier (5.1 ± 0.4 μm/min, SE) than against an uncoated barrier (18 ± 2 μm/min, SE) (p-value 4.7*10−23; Figure 3CD). While generating a pulling force, the MT shrinkage velocity was even lower (Table S1, Figure 3F), as expected (Akiyoshi et al., 2010). Detailed analysis of the shrinkage events shows that in the presence of dynein and ATP, occasional switches from ‘slow’ (<10 μm/min; indicated in black) to ‘fast’ (> 10 μm/min; indicated in red) MT shrinkage were observed (Figure 3C). We postulate that such slow-to-fast switches reflect the loss of dynein-mediated interactions with the barrier either through dynein’s detachment from the MT or through dynein’s detachment from the barrier. In the absence of ATP, MT shrinkage was almost completely stalled (0.15 ± 0.04 μm/min, SE). The fact that some motion was still observed in this case may be consistent with the observation that single dynein molecules, assisted by an external force, are able to move slowly in the absence of ATP (Gennerich et al., 2007). Alternatively, the residual motion could be due to the presence of GTP (our unpublished results on dynein gliding assays with GTP).

Aside from confirming that barrier-attached dynein reduces the MT shrinkage velocity, the optical trap experiments provide again evidence that barrier-attached dynein increases the catastrophe frequency. To clearly reveal this effect, we increased the tubulin concentration and temperature in our samples. In the absence of dynein, this leads to the formation of a bundle of growing MTs that experience ‘collective’ catastrophes, which occur much more infrequently than individual catastrophes (Laan et al., 2008). We found however that MTs growing against a dynein-coated barrier, retained a short catastrophe time, indicating that frequent catastrophes prevented MT bundles from forming (Figure S3).

Dynein-Mediated Pulling Forces Contribute to Efficient Aster Positioning

Having established that barrier-attached dynein can regulate MT dynamics and length, and mediate the generation of pulling forces, the question remaining to be answered is whether this MT-dynein interaction allows a MT-organizing center to reliably position itself with respect to the confining geometry of a cell. In cells, the details of positioning differ between systems and situations. To establish the basic mechanism by which cortical MT-dynein interactions may contribute to positioning processes, we focus here on the simplest situation: the positioning of a single MT-organizing center in a symmetric geometry. In our minimal in vitro experiments, dynamic MT asters, grown from centrosomes, were confined in three dimensions to microfabricated square chambers. A gold layer sandwiched in the sidewalls of the microfabricated chambers allowed for specific binding of biotinylated dynein molecules (Figure 4ABC). We varied the amount of dynein molecules in the experiments by varying the thickness of the gold layer. Pushing forces were generated by growing MTs that were in contact with the walls and exerted polymerization forces and/or elastic restoring forces due to MT buckling. Pushing MTs became pulling MTs once they were captured by dynein molecules.

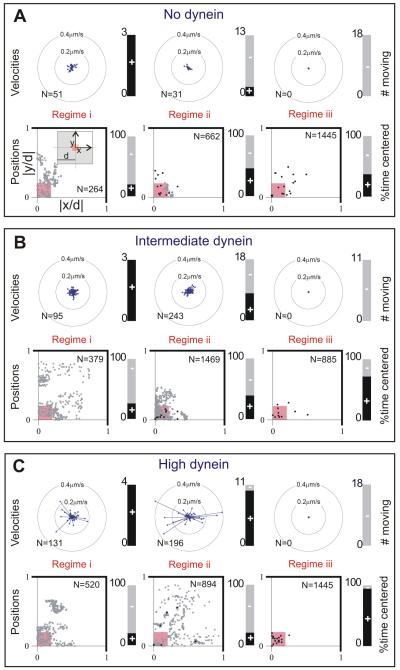

We performed experiments with three different amounts of dynein molecules bound to the sidewalls of the microfabricated chambers: no dynein, dynein bound to a 100 nm thick gold layer, and dynein bound to a 700 nm thick gold layer (Figure 4DEF). We observed the positioning process in three regimes, where the average MT length was (i) shorter, (ii) approximately equal, or (iii) longer than the half-width of the microfabricated chamber d. This corresponds to aster behavior at early, intermediate, and late times in the experiment. In these three regimes, we tracked the x and y positions of the MT asters in the microfabricated chambers for a few minutes (see Figure S5 for example traces). For each aster, we calculated the directions and magnitudes of the centrosome velocities to determine if the aster was moving, and recorded the absolute position normalized to the chamber half-width d to determine if the MT aster was centered (Figure 5). Here, moving was defined as moving more than 1 pixel (165 nm) in 150 s, and centered was defined as being located within the central square 4% area of the chamber (scheme in Figure 5A; for details see Supplemental Information).

Figure 5. MT aster positions and movements.

(A,B,C) Data are shown for the same conditions and regimes as displayed in Figure 4DEF. Top: rosette plots show the magnitude and the direction of velocity of all moving centrosomes. The velocity was determined over 15 s time intervals. The directions are binned into 16 angles. The lengths of the arrows indicate the average velocity in that direction for all time intervals, where N is the total number of time intervals per condition. The stacked bar plots show the number of centrosomes that moved (black, +). Bottom: scatter plots of all aster positions, normalized with d, plotted in one quadrant of the chamber, as indicated in the left-most plot in A (N is the total number of time points, n the number of asters). Aster positions within the small pink square are considered centered. Grey dot indicates one time point; black point indicates more than 10 time points at the same position. Mean positions and standard deviations are given in Table S2. The stacked bar plots show the percentage of time that centrosomes were centered (black, +).

In regime (i), aster behavior was at first sight similar for different dynein densities: the MT aster moved in a diffusion-like manner through the microfabricated chamber, and the centrosomes were found in the center only around 20% of the time. However, quantification of the velocities of the centrosomes shows that the centrosomes moved faster at high dynein amounts, suggesting occasional pulling interactions with dynein. In regime (ii), different dynein amounts led to different behaviors. If dynein was not present, MTs only exerted pushing forces. Around 20% of the MT asters moved, and the centrosomes were found centered around 50% of the time, with their MTs slightly buckled, consistent with previous results (Faivre-Moskalenko and Dogterom, 2002; Holy et al., 1997). At intermediate dynein amounts, asters moved in almost half of the cases, although they never moved very fast, nor very far from the center. At high dynein amounts, the movement of the MT asters was most dramatic: the asters moved throughout the whole microfabricated chamber, with higher velocities than in the absence of dynein (see also Movie S5). Due to these movements the centrosomes spent only around 20% of the time in the center. Apparently, more and more MTs start to be captured by dynein molecules due to contacts between MT ends and the chamber walls. However, the pulling forces generated by initially only a few MTs do not balance each other, resulting in dramatic movements of the MT asters and disruption of the centering process. In regime (iii), the MTs were long and there was no observable movement of the asters for any given amount of dynein. When dynein was absent, the MTs strongly buckled and around 40% of the centrosomes were centered, similar to what was observed in regime (ii). Interestingly, in regime (iii), the presence of dynein significantly improved the centering of the asters. At intermediate dynein amounts around 70%, and at high dynein amounts 95% of the observed centrosomes were centered (see also Movie S6). Especially at high dynein densities, MTs did not buckle, but remained straight, which is in strong contrast to the long buckled MTs observed in the absence of dynein. This suggests that, in contrast to regime (ii), dynein has now captured almost all MT ends, leading to an effective control of MT length and a balance of forces on the MT asters that drives them to the middle of the chambers. Note that the MTs establish again only end-on contacts with dynein at the barrier.

Centering of MT Asters Due to a Combination of Pushing and Pulling Forces

In the past, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain dynein-mediated positioning processes observed in living cells. In many cases, these positioning mechanisms relied on the assumption of length-dependent pulling forces due to lateral interactions of pulling force generators along the length of MTs (Hamaguchi and Hiramoto, 1986), either at the cortex or in the cytoplasm (Kimura and Kimura, 2011; Wuhr et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2010). Here, we show using a physical description of aster mechanics that includes MT dynamics and the effects of pushing and pulling forces at the chamber sidewalls, that centering can be reliably achieved by length-independent cortical pulling forces (Figure 6). Our simple model is described in Box 1: we distinguish two time-dependent populations of centrosome-nucleated MTs that are in contact with a confining boundary. Growing MTs exert pushing forces that are limited in magnitude by the length-dependent buckling force of MTs. Shrinking MTs that are captured by dynein molecules exert a constant pulling force. A key ingredient of our model is that pushing MT ends may grow and slip along the walls, before they are captured by dynein molecules and become pulling MT ends (as experimentally observed; see Figure 1).

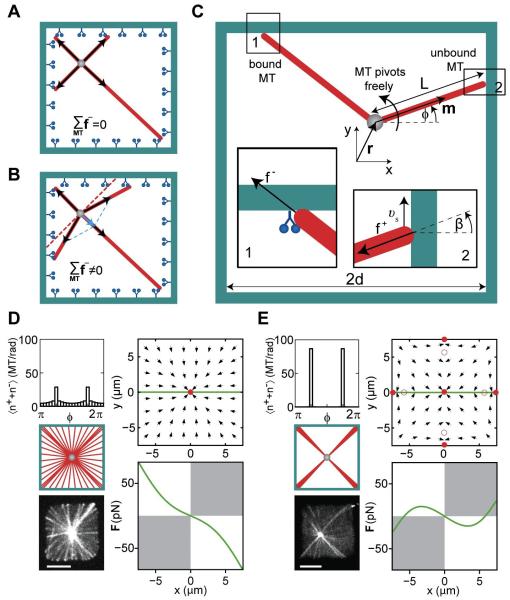

Figure 6. Theory of aster positioning.

Cartoon showing the net pulling force without (A) and with MT slipping (B). (C) Schematic representation of a MT organizing center at r=(x,y) in a confining geometry. The MT orientation is described by the angle φ, the MT length is denoted by L. Inset 1 shows a MT under pulling force f−. Inset 2 shows a MT under pushing force f+, which slips along the wall with velocity νs. The angle between the MT orientation and the normal to the boundary is β. (D,E) Angular MT distributions and the corresponding force direction fields for a MT organizing center in a chamber with (D; kb=0.02 s−1) and without dynein (E; kb =0 s−1). Full and hollow red circles show the stable and unstable force-balanced states, and the green line indicates the positions for which the forces are shown below. White quadrants indicate where the force is centering. Other parameters (see Box 1) are kcat = 10−4 s−1, koff = 10−3 s−1, = 5 pN, ζ = 5·10−5 N·s/m, κ = 3.3·10−23 Nm2, M=50. For comparison, images of a MT aster in a microfabricated chamber with (D), and without dynein (E) are shown. Scalebars indicate 5 μm.

Box 1: Theoretical description of MT aster mechanics in a confining geometry.

In our description of aster mechanics, MTs radiate from an organizing center located at position r (Figure 6C). Two time-dependent populations of MTs are in contact with a confining boundary: (i) pushing MTs distributed with angular density n+(φ,t), and (ii) pulling, dynein-attached MTs distributed with angular density n−(φ,t). Here φ describes the MT orientation relative to the x-direction and t denotes time. These MT distributions obey the following kinetic equations:

| (B1) |

| (B2) |

Here ν denotes the nucleation rate of MTs at the organizing center (assuming that all nucleated MTs reach the boundary), kcat denotes the rate at which pushing MTs release from the boundary, kb denotes the rate of MT capture by dynein, and koff denotes the detachment rate of pulling MTs. Note that these equations do not include the growth and shrinkage velocities of MTs. The tangential flux of pushing MT ends

| (B3) |

describes the reorientation of pushing MTs due to slipping along the boundary. Here, is the rate of angular MT reorientation, where L(r,φ) is the distance between the organizing center at r and the MT contact with the boundary, and β(r,φ) is the angle between the MT orientation and the normal to the boundary. The slipping velocity is , where f+ denotes the force exerted by a pushing MT on the boundary in a direction given by the angle φ, and ζ is the friction coefficient associated with slipping. The net force acting on the organizing center is given by F = F+ + F−, where

| (B4) |

correspond to the net pushing and pulling forces, respectively. Here, m(φ) denotes the unit vector in the direction of the MT at an angle φ. The pushing force of a single MT is approximated as f+ = π2k/L2, where k denotes the MT bending rigidity. The pulling force f− > 0 is constant. In steady state, ∂tn+ = ∂tn− = 0 and the nucleation rate is ν = M(kcat + kb)/(1 + kb/koff), where M is the total number of MTs in contact with the boundary, which assumes a finite number of nucleation sites at the organizing center. A more detailed discussion of the model and choice of parameters is presented in the Supplemental Information.

The unstable behavior induced by dynein pulling as observed in regimes (i) and (ii) occurs if MT lengths are typically shorter than the chamber size. Under these conditions our theory suggests that pulling forces generally destabilize centering (Figure S6D). However, when MT lengths are typically long enough to reach the chamber boundaries, the model predicts stable centering, as we indeed experimentally observe in regime (iii). This can be understood as follows: without slipping, the ends of isotropically nucleated MTs would remain isotropically distributed along the chambers walls upon capture by dynein molecules, resulting in a net zero pulling force on the centrosome (Figure 6A). By contrast, slipping leads to an anisotropic distribution of MT ends along the chambers walls, and a corresponding net centering force on the centrosome (Figure 6B). Analysis of the model shows that for every aster position r, the net steady state centering force F due to pulling is directed towards a unique stable force-balanced state in the center (Figure 6D). Only when the capture of MTs by dynein is fast, and slipping is suppressed, do pulling forces fail to cause centering (Figure S6B).

When dynein is absent, the model also predicts a net force towards the center of the chamber due to pushing MTs. This centering by pushing is due to the length-dependence of the pushing force, as proposed in previous work (Dogterom et al., 2005; Dogterom and Yurke, 1998; Faivre-Moskalenko and Dogterom, 2002; Howard, 2006; Zhu et al., 2010). However, if the MT aster is too far from the center, pushing forces do not lead to centering. We find four additional force-balanced states at the middle of each edge of the square, where off-centering effects due to the anisotropic MT distribution take over (Figure 6E). Note that our model does not describe the effect of MT curvature due to buckling of long MTs that occurs in regime (iii) in the absence of dynein. Buckled MTs introduce additional off-centering forces (Faivre-Moskalenko and Dogterom, 2002; Holy et al., 1997; Kimura and Kimura, 2011), which reduce the accuracy of centering, as observed in our experiments (Figure 5A). Taken together, these theoretical findings, which are qualitatively the same for a large range of parameters (Figure S6C), lead us to conclude that in simple symmetric geometries such as considered here, pulling forces in combination with MT slipping provide a more reliable centering mechanism than pushing alone.

DISCUSSION

Coupling of MT and Dynein Dynamics

In our experiments we observe a tight coupling between MT dynamics and dynein activity that appears to be a result of the ‘end-on’ contact between the MT end and the barrier. The alternative configuration, in which a MT is interacting ‘laterally’ with a dynein-covered surface, does not lead to the same behavior. Depending on the geometry of the interaction between dynein and MTs in cells, one may thus find distinctly different direct regulatory effects on MT dynamics. We propose that the difference in behavior between end-on and lateral contacts can be explained in the following way: growing MT ends that are captured by barrier-attached dynein are observed to switch to a shrinking state. We have shown that this is not the result of a depolymerizing activity of dynein, and we instead propose that dynein induces a catastrophe simply by holding the MT with its growing end against the barrier. This hinders further growth which results in a catastrophe (Janson et al., 2003). In a ‘gliding’ configuration, or in general when dynein is coupled to a lateral cargo, dynein cannot trigger catastrophes in this way because it is not coupled to a barrier that prevents MT growth. Following a catastrophe, dynein cannot move at its preferred velocity, as it depends on MT shrinkage: without MT shrinkage (or severe bending of the MT end), the MT cannot be pulled further towards the barrier, and as a result, dynein is unable to move in the direction of the MT minus-end. We further propose that MT shrinkage is hindered when dynein is connected to the very MT end. We speculate that barrier-attached dynein slows shrinkage by mechanically preventing protofilaments from curling outwards, as has been proposed for the Dam1 complex (Franck et al., 2007). In an end-on configuration, it is possible that two (or more) dynein molecules interact with protofilaments on opposite sides of the MT, which may enhance the effectiveness of this mechanism. In a lateral configuration there are no constraints to keep the dynein molecule strictly associated with the MT end. Since the motor does not need to wait for the MT to shrink, it can walk at full speed. This results in a lower effective concentration of dynein molecules at the MT end, which can furthermore only interact with protofilaments on one side of the MT, explaining the less pertinent effect on MT shrinkage.

Regulation of Cortical MT Dynamics in Vivo

Although our results demonstrate that the regulation of MT dynamics and the generation of pulling forces are intrinsic capabilities of cortical MT-dynein interactions, it is well known that in vivo other factors, which vary between different systems, contribute to the proper regulation of MT forces and dynamics. In fact, typical values for both the MT growth velocity and the catastrophy frequency are higher in living cells than what is observed with pure tubulin in vitro (Desai and Mitchison, 1997). Keeping in mind that it is therefore not straightforward to interpret the effects of cortical dynein (deletions) on MT dynamics in vivo, our results may provide a direct explanation for several in vivo observations. During meiotic prophase in S. pombe, astral MTs shrink more than two times faster in cells lacking dynein compared to wild type cells (Yamamoto et al., 2001). The authors propose that a MT-disassembling factor might be involved in this effect, but our study raises the possibility that dynein itself is responsible for the regulation of MT shrinkage. In S. cerevisiae, in G2/M phase, MTs that grow into the bud shrink two times faster in mutants where dynein is effectively removed from the cortex (Adames and Cooper, 2000). The interaction with dynein at the cortex of a subset of MTs may cause the slower (average) rates of MT shrinkage in wild type cells. Note, however, that conflicting results, suggesting that MTs grow slower instead of faster in a dynein mutant, have also been published (Carminati and Stearns, 1997). In wild-type C. elegans embryos, it has been shown that MTs which establish contacts with the cortex have an enhanced catastrophe frequency due to the presence of a specific regulatory factor (EFA-6) (O’Rourke et al., 2010). Besides having a direct effect on the MT catastrophe rate, it is possible that such a factor indirectly affects the catastrophe frequency by influencing the relative activity of lateral versus end-on cortical dynein contacts (Gusnowski and Srayko, 2011). If predominantly lateral contacts were established in the absence of a regulatory factor, dynein would no longer lead to an increase of the catastrophe rate. Clearly, to establish the direct role of cortical dynein in the regulation of MT dynamics in these and other cases, it will be necessary to specifically measure the dynamics of MT ends that are in contact with the cortex, and compare them to MT dynamics in the cytoplasm in wild-type and dynein-deficient cells.

Positioning of MT Organizing Centers in Cellular Geometries

Our work suggests that cortical MT-dynein interactions may play a key role in cellular positioning processes. The centering mechanism we propose relies on the idea that growing MT ends can slip along cellular boundaries. In our in vitro experiments, such slipping (Figure 1F) and the predicted anisotropy MT distributions are readily observed (see Figure 6DE, Figure S4). An important question is whether slipping can be observed in living cells. In previous experiments where MTs or MT plus ends were fluorescently labeled, tracks of growing MTs revealed motion of MT ends along the cell cortex (see e.g. (Komarova et al., 2009) for mammalian cells or (Minc et al., 2009) for fission yeast). These observations suggest that MT slipping occurs in living cells. In addition, it has been shown that the distribution of MT orientations depends on cell shape, and it has been suggested that MT slippage is responsible for this (Picone et al., 2010). In the future, it will be interesting to directly test whether MT distributions in living cells are consistent with MT slipping at cellular boundaries in situations where cortical pulling forces drive positioning processes.

Implications for other MT-dynein interactions

Finally, our results may have implications for other cellular processes where dynein interacts with dynamic MT ends. An important example is the interaction between MT ends and kinetochores during dynein-mediated poleward motion of chromosomes (Savoian et al., 2000; Sharp et al., 2000). In this context, dynein might serve to stabilize the end-on attachment between kinetochores and shrinking MT ends, and control the speed of chromosome motion during anaphase. Our experiments show that dynein molecules can be locked for some time in a configuration where the detachment rate from the MT end is reduced (Figure 1D), even in the presence of ATP (consistent with previous observations on stalled single dynein molecules (Gennerich et al., 2007)). Interestingly, this could explain the observation that dynein under tension can stabilize MT attachment at kinetochores (Varma et al., 2008). In addition to regulating MT dynamics and participating in the generation of pulling forces, our results show that cytoplasmic dynein can efficiently couple cargo to the ends of depolymerizing MTs, as has been previously reported for flagellar dynein, the DAM1 complex, and plus-end directed motors such as members of the kinesin-1 and kinesin-8 families (Franck et al., 2007; Grissom et al., 2009; Lombillo et al., 1995; Powers et al., 2009). An important added insight from our results is that such coupling can function in a configuration where the motor protein is attached to a barrier that faces the dynamic MT end-on, as was recently reported for the depolymerizing motor MCAK interacting with stabilized MTs (Oguchi et al., 2011).

We conclude that our experiments reveal intrinsic biophysical properties of end-on MT-dynein interactions that are likely to be important for a wide range of cellular processes, including the positioning processes that are the focus of this work.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Tubulin was purchased from Cytoskeleton Inc. (Denver). Dynein constructs used were the biotinylated GST-dynein331 construct (referred to as dynein) as well as the GST-dynein331 E2488Q construct, which contains a GFP (referred to as dynein AAA3E/Q-GFP) (Cho et al., 2008; Reck-Peterson et al., 2006).

Microfabrication and Functionalization of Gold Barriers and Chambers

The microfabricated barriers and chambers were made and labeled with biotin as described in (Laan and Dogterom, 2010). A multilayer of three layers of streptavidin and two layers of biotinylated BSA was bound to the biotinylated gold, ending with a layer of biotinylated dynein (Romet-Lemonne et al., 2005). Alternatively (Figure 1EGH), only one layer of streptavidin was used, and biotinylated dynein was diluted with biotinylated BSA.

MTs Growing against Gold Barriers

Rhodamine-labeled MTs nucleated from surface-attached centrosomes were imaged at 25°C on a Leica microscope with a 100×, 1.3 NA oil immersion objective, equipped with a spinning disk confocal head from Yokogawa and a cooled EM-CCD camera (C9100, Hamamatsu Photonics). For the analysis of MT dynamics (see Supplemental Information), data were collected from 3-6 independent experiments for every condition.

Optical Trap Experiments

We used a “key hole” trap as described in (Kerssemakers et al., 2006). Trap stiffnesses in the range of 0.025-0.035 pN/nm were used. Experiments were performed at 25°C. The position of the bead was measured at video-rate (25 Hz) and used to determine MT length changes and forces. Shrinking events were identified by eye in 3-6 independent experiments for each condition (Table S1).

Positioning Experiments in Microfabricated Chambers

Microfabricated chambers and poly-dimethylsiloxane (PDMS) lids were assembled into a temporary flowcell, placed on a metal block at 4°C. After surface blocking, functionalization, and the introduction of centrosomes and tubulin, the PDMS coverslip was pressed on the microfabricated chambers. For every dynein amount, centrosomes were imaged in 5 different samples. The position of the centrosome in the microfabricated chamber was tracked using the automatic ImageJ plugin spot tracker (Sage et al., 2005).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This collaborative project benefited greatly from interactions during the Physiology Course at the MBL, Woods Hole. All experiments were performed by LL, together with JH (optical trap) and MPL (supplemental gliding assays), based on chamber functionalization technology developed by GRL and MvD, under supervision of MD. RV and SRP provided materials and expertise on dynein. Theory was developed by NP and LL, under supervision of FJ. We thank M. Footer for providing us with axonemes, C. Celati for help with the centrosome purifications, E.L. Munteanu and J.W.J. Kerssemakers for developing the optical trap set-up, C. Rétif, H. Bar, and M. Seynen for technical support, and S. Kryazhimskiy for help with statistical analysis. Financial support from the European network Active BIOMICS, and from HFSP is gratefully acknowledged. This work is part of the research program of the “Stichting voor Fundamenteel Onderzoek der Materie (FOM)”, which is financially supported by the “Nederlandse organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO)”.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes six figures, six movies, two tables, and extended Experimental and Theoretical Procedures.

REFERENCES

- Adames NR, Cooper JA. Microtubule interactions with the cell cortex causing nuclear movements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:863–874. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyoshi B, Sarangapani KK, Powers AF, Nelson CR, Reichow SL, Arellano-Santoyo H, Gonen T, Ranish JA, Asbury CL, Biggins S. Tension directly stabilizes reconstituted kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Nature. 2010;468:576–579. doi: 10.1038/nature09594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burakov A, Nadezhdina E, Slepchenko B, Rodionov V. Centrosome positioning in interphase cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:963–969. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carminati JL, Stearns T. Microtubules orient the mitotic spindle in yeast through dynein-dependent interactions with the cell cortex. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:629–641. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F, Nurse P. How fission yeast fission in the middle. Cell. 1996;84:191–194. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho C, Reck-Peterson SL, Vale RD. Regulatory ATPase sites of cytoplasmic dynein affect processivity and force generation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25839–25845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802951200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CR, Hyman AA. Asymmetric cell division in C. elegans: cortical polarity and spindle positioning. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:427–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.113823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogterom M, Kerssemakers JW, Romet-Lemonne G, Janson ME. Force generation by dynamic microtubules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogterom M, Yurke B. Measurement of the force-velocity relation for growing microtubules. Science. 1997;278:856–860. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogterom M, Yurke B. Microtubule dynamics and the positioning of microtubule organizing centers. Physical Review Letters. 1998;81:485–488. [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin DL, Vallee RB. Dynein at the cortex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:44–49. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre-Moskalenko C, Dogterom M. Dynamics of microtubule asters in microfabricated chambers: the role of catastrophes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16788–16793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252407099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck AD, Powers AF, Gestaut DR, Gonen T, Davis TN, Asbury CL. Tension applied through the Dam1 complex promotes microtubule elongation providing a direct mechanism for length control in mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:832–837. doi: 10.1038/ncb1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennerich A, Carter AP, Reck-Peterson SL, Vale RD. Force-induced bidirectional stepping of cytoplasmic dynein. Cell. 2007;131:952–965. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill SW, Gonczy P, Stelzer EH, Hyman AA. Polarity controls forces governing asymmetric spindle positioning in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Nature. 2001;409:630–633. doi: 10.1038/35054572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishchuk EL, Molodtsov MI, Ataullakhanov FI, McIntosh JR. Force production by disassembling microtubules. Nature. 2005;438:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature04132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissom PM, Fiedler T, Grishchuk EL, Nicastro D, West RR, McIntosh JR. Kinesin-8 from fission yeast: a heterodimeric, plus-end-directed motor that can couple microtubule depolymerization to cargo movement. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:963–972. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusnowski EM, Srayko M. Visualization of dynein-dependent microtubule gliding at the cell cortex: implications for spindle positioning. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:377–386. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi MS, Hiramoto Y. Analysis of the role of astral rays in pronuclear migration in sand dollar eggs by the colcemid-UV method. Development Growth & Differentiation. 1986;28:143–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1986.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holy TE, Dogterom M, Yurke B, Leibler S. Assembly and positioning of microtubule asters in microfabricated chambers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6228–6231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J. Elastic and damping forces generated by confined arrays of dynamic microtubules. Phys Biol. 2006;3:54–66. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/3/1/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson ME, de Dood ME, Dogterom M. Dynamic instability of microtubules is regulated by force. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:1029–1034. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerssemakers JW, Munteanu EL, Laan L, Noetzel TL, Janson ME, Dogterom M. Assembly dynamics of microtubules at molecular resolution. Nature. 2006;442:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature04928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Kimura A. Intracellular organelles mediate cytoplasmic pulling force for centrosome centration in the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:137–142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova Y, De Groot CO, Grigoriev I, Gouveia SM, Munteanu EL, Schober JM, Honnappa S, Buey RM, Hoogenraad CC, Dogterom M, et al. Mammalian end binding proteins control persistent microtubule growth. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:691–706. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonce MP, Kohler J, Neujahr R, Schwartz JM, Tikhonenko I, Gerisch G. Dynein motor regulation stabilizes interphase microtubule arrays and determines centrosome position. EMBO J. 1999;18:6786–6792. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski C, Srayko M, Nedelec F. Cortical microtubule contacts position the spindle in C. elegans embryos. Cell. 2007;129:499–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laan L, Dogterom M. In vitro assays to study force generation at dynamic microtubule ends. Methods Cell Biol. 2010;95:617–639. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(10)95031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laan L, Husson J, Munteanu EL, Kerssemakers JW, Dogterom M. Force-generation and dynamic instability of microtubule bundles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8920–8925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710311105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe JC, Maddox PS, Salmon ED, Goldstein B. PAR proteins regulate microtubule dynamics at the cell cortex in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2003;13:707–714. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombillo VA, Stewart RJ, McIntosh JR. Minus-end-directed motion of kinesin-coated microspheres driven by microtubule depolymerization. Nature. 1995;373:161–164. doi: 10.1038/373161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JR, Volkov V, Ataullakhanov FI, Grishchuk EL. Tubulin depolymerization may be an ancient biological motor. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3425–3434. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minc N, Bratman SV, Basu R, Chang F. Establishing new sites of polarization by microtubules. Curr Biol. 2009;19:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Ngoc T, Afshar K, Gonczy P. Coupling of cortical dynein and G alpha proteins mediates spindle positioning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1294–1302. doi: 10.1038/ncb1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke SM, Christensen SN, Bowerman B. Caenorhabditis elegans EFA-6 limits microtubule growth at the cell cortex. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1235–1241. doi: 10.1038/ncb2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguchi Y, Uchimura S, Ohki T, Mikhailenko SV, Ishiwata S. The bidirectional depolymerizer MCAK generates force by disassembling both microtubule ends. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:846–852. doi: 10.1038/ncb2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picone R, Ren X, Ivanovitch KD, Clarke JD, McKendry RA, Baum B. A polarised population of dynamic microtubules mediates homeostatic length control in animal cells. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AF, Franck AD, Gestaut DR, Cooper J, Gracyzk B, Wei RR, Wordeman L, Davis TN, Asbury CL. The Ndc80 kinetochore complex forms load-bearing attachments to dynamic microtubule tips via biased diffusion. Cell. 2009;136:865–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck-Peterson SL, Yildiz A, Carter AP, Gennerich A, Zhang N, Vale RD. Single-molecule analysis of dynein processivity and stepping behavior. Cell. 2006;126:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romet-Lemonne G, VanDuijn M, Dogterom M. Three-dimensional control of protein patterning in microfabricated devices. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2350–2354. doi: 10.1021/nl0507111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage D, Neumann FR, Hediger F, Gasser SM, Unser M. Automatic Tracking of Individual Fluorescence Particles: Application to the Study of Chromosome Dynamic. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 2005;14:1372–1383. doi: 10.1109/tip.2005.852787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoian MS, Goldberg ML, Rieder CL. The rate of poleward chromosome motion is attenuated in Drosophila zw10 and rod mutants. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:948–952. doi: 10.1038/35046605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmoranzer J, Kreitzer G, Simon SM. Migrating fibroblasts perform polarized, microtubule-dependent exocytosis towards the leading edge. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4513–4519. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DJ, Rogers GC, Scholey JM. Cytoplasmic dynein is required for poleward chromosome movement during mitosis in Drosophila embryos. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:922–930. doi: 10.1038/35046574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchcombe JC, Majorovits E, Bossi G, Fuller S, Griffiths GM. Centrosome polarization delivers secretory granules to the immunological synapse. Nature. 2006;443:462–465. doi: 10.1038/nature05071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PT, Marsh L, Doye V, Inoue S, Chang F. A mechanism for nuclear positioning in fission yeast based on microtubule pushing. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:397–411. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee RB, Varma D, Dujardin DL. ZW10 function in mitotic checkpoint control, dynein targeting and membrane trafficking: is dynein the unifying theme? Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2447–2451. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma D, Monzo P, Stehman SA, Vallee RB. Direct role of dynein motor in stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment, orientation, and alignment. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1045–1054. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel SK, Pavin N, Maghelli N, Julicher F, Tolic-Norrelykke IM. Self-organization of dynein motors generates meiotic nuclear oscillations. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuhr M, Dumont S, Groen AC, Needleman DJ, Mitchison TJ. How does a millimeter-sized cell find its center? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1115–1121. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.8.8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Tsutsumi C, Kojima H, Oiwa K, Hiraoka Y. Dynamic behavior of microtubules during dynein-dependent nuclear migrations of meiotic prophase in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3933–3946. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.12.3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Burakov A, Rodionov V, Mogilner A. Finding the cell center by a balance of dynein and myosin pulling and microtubule pushing: a computational study. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:4418–4427. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.