Abstract

School health programmes as a platform to deliver high-impact health interventions are currently underrated by decision makers and do not get adequate attention from the international public health community. We describe the award-winning Fit for School Approach from the Philippines as an example of a large-scale, integrated, cost-effective and evidence-based programme that bridges the gap between sectors, and between evidence and practice. In view of the challenges to achieve the health and education related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in many countries, intensified efforts are required. We present the Fit for School Action Framework as a realistic and tested approach that helps to make schools places of public health for children and wider communities.

Keywords: integrated school health, child health, child education, evidence-based intervention, community health, Fit for School

Health and education are still considered major public goods and the responsibility of states and governments. However, we believe that the potential of schools as public places to promote public health is largely underestimated by health and education decision makers, but also by the wider public health community (1). While many countries have policies related to school health, the complexities of implementing large-scale school-based health programmes often lead to a gap between intention and practice. Difficulties in overcoming barriers to intersectoral collaboration between health, sanitation and education, administrations trapped in vertical thinking, and lack of leadership are among the reasons for an all-too often untapped potential of school health (2). While basic health education is a topic on most national model curricula efforts often stop there and reduce schools to places of educational knowledge transfer, ignoring the huge potential for tangible and sustained behaviour change through a skills-based approach. Furthermore, schools are not only education facilities for children, but also centres of community life and can play a pivotal leadership role in changing living conditions of the communities surrounding them by addressing key determinants of health.

It is not without reason that four out of eight MDGs focus on child health and education – areas where international public health and development efforts so far have failed to address even the most pressing needs; but also areas where improvements may have the greatest benefit for human development and poverty reduction. Preventable infections and chronic diseases take a high toll on the child population globally, with more than 200 million children not reaching their full physical and cognitive developmental potential, and about 10 million dying per year from preventable causes (3, 4). The report of the WHO's Commission on Social Determinants of Health highlighted with painful clarity that poverty, lack of access to safe water and sanitation and inequities are major factors contributing to poor child health in many countries (5). Unfortunately, ignorance of determining factors and the overwhelming scale of problems have led to a social acceptance of certain conditions, which are too often seen as inevitable or unaffordable to tackle, despite existing good evidence for cost-effective interventions (6).

The Fit for School (FIT) Approach, an innovative integrated school health concept implemented in public elementary schools in the Philippines under the Department of Education's ‘Essential Health Care Program’ (EHCP), combines evidence-based interventions against some of the most prevalent diseases among school children: worm infections, hygiene-related infections such as diarrhoea and respiratory infections, as well as rampant tooth decay (7–9). The programme implements hand washing with soap and tooth brushing with fluoride toothpaste as daily group activities run by teachers; and is complemented by biannual deworming, also done by teachers. This goes hand in hand with improvements in water and sanitation where parents and the community are actively involved in the construction of washing facilities or the provision of clean water to schools without access, thus tackling key determinants of health. The EHCP currently targets more than two million Filipino children. Material costs of 0.50USD/child/year make the programme very affordable so that it can be integrated in the regular budgets of local government units, thus ensuring sustainability beyond external funding, donations or corporate sponsorship. In the Philippines the NGO Fit for School Inc., supported by major international development agencies (German Development Cooperation GIZ, AusAID and UNICEF) provides capacity development, technical support for monitoring and evaluation as well as advocacy with all concerned partners. The recognition through international awards such as the Award for ‘Innovation in Global Health’ (2009) from the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme, and the World Health Organization; and the Poverty Reduction, Equity and Growth Network (PEGNet) Award for effectively linking research and practice, highlight the model character of FIT and of school health in general (10, 11). These factors have all contributed to an increased interest from other countries throughout Asia resulting in three other Southeast Asian countries now implementing the FIT Approach, a process in partnership with the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Association (SEAMEO).

The Fit for School Action Framework

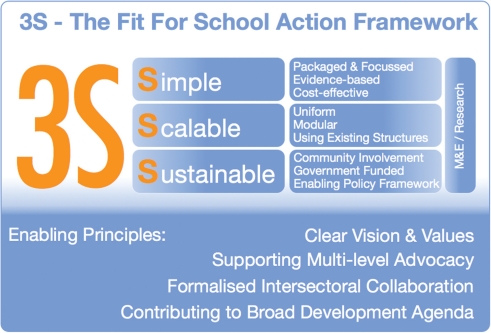

International policy frameworks for school health, particularly the UNESCO-led FRESH approach (12) and the WHO Health Promoting School concept (13) provide the conceptual context for the innovative Fit for School Action Framework, which is the basis of operation for the FIT Approach (see Fig. 1). The core of the Fit for School Action Framework are the three ‘Ss’: Simple, scalable and sustainable. These are key characteristics of any successful large-scale school health programme.

Simple: Interventions in school health must be based on best possible evidence, should be cost-effective and are more likely to achieve high impact if only a few key diseases are at focus and the interventions are packaged to make implementation as easy as possible.

Scalable: The FIT Approach shows that large-scale implementation is possible if interventions follow a modular structure and are based on uniform templates. Using existing structures and resources is an essential part of scalability, such as relying on a few simple interventions implemented by teachers, rather than health professionals.

Sustainable: Any programme will only be successful in the long run if it is not donor-dependent. The FIT Approach is based on the principle of sustained government funding after an initial start-up phase. It also actively involves actively communities and parents in the programme through a participative monitoring and evaluation (M&E) process or through the construction of required group washing facilities. A supporting policy framework that addresses macro- and micro-management issues alike is key in ensuring sustainability. Effective and appropriate research and monitoring complement and inform the programme management as well as political decision makers.

Fig. 1.

The Fit for School Action Framework.

A set of simple enabling principles is helping to pragmatically bridge the gap between well-intended policy and real-life implementation: clear agreements between stakeholders on vision and values of the programme, a formalised intersectoral collaboration and advocacy at the different levels of the health and education system, addressing the broad range of stakeholders on local, regional and national levels. In this context it helps to demonstrate that effective school health contributes to different sectors of the overall development agenda.

Effective school health, embedded in a community context, driven by the education sector and supported by the health and sanitation sectors produces benefits across many areas, makes schools healthier places and thus tackles determinants of health and contributes to greater health equity – all of this at exceptionally low cost. Preventing diseases at an early age and promoting healthy life-skills promises huge long-term returns. ‘The question now is not whether school health programs are necessary (…), but how they can be implemented at meaningful scale in the poorest countries, which need them the most. This is the challenge that we now face’ (14). We could not agree more with this statement from Donald Bundy, the World Bank's leading expert on school health. The inclusion of school health in the declaration of the UN High-Level Meeting on Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) is a step in the right direction to address the growing tide of NCDs and puts effective school health back on political agendas worldwide (15). The Philippines and the successful Fit for School Approach are at the forefront of intensified efforts to revitalise school health as a platform for concerted intersectoral public health action addressing health and education, but also key determinants of development progress. Further information about Fit for School is available at: www.fitforschool.ph

Conflict of interest and funding

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. No funding was received to draft this comment and no ethics approval was required.

References

- 1.Lear JG. Health at school: a hidden health care system emerges from the shadows. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:409–19. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiscella K, Kitzman H. Disparities in academic achievement and health: the intersection of child education and health policy. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1073–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:60–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361:2226–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaglehole R, Bonita R. Global public health: a scorecard. Lancet. 2008;372:1988–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monse B, Benzian H, Panse R. Fit for School. Development and Cooperation. 2008;49:434–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monse B, Naliponguit E, Belizario V, Benzian H, van Palenstein Helderman W. Essential health care package for children – the ‘Fit for School’ program in the Philippines. Int Dent J. 2010;60:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Lancet. Oral health: prevention is key (Editorial) Lancet. 2009;373:1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) New York: UNDP; 2010. Special unit for south-south cooperation. Solutions! Global South-South Development Expo 2009 Report. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poverty Reduction, Equity and Growth Network (PEGNet) Kiel: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW); 2011. Third Best Practice Award at PEGNet Conference 2011 [Internet] Available from: http://www.pegnet.ifw-kiel.de/activities/best-practice-award/the-pegnet-best-practice-award [cited 10 November 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2012. School and youth health. What is a health promoting school? Available from: http://www.who.int/school_youth_health/gshi/hps/en/index.html [cited 20 January 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNESCO. Paris: UNESCO; 2011. FRESH. a comprehensive school health approach to achieve EFA. Available from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001255/125537e.pdf [cited 20 January 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundy D. Rethinking School Health: a key component of education for all. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations. Resolution A/66/L1. New York: United Nations; Political declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. 16 September 2011. Available from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A%2F66%2FL.1&Lang=E [cited 11 November 2011] [Google Scholar]