Abstract

Hydrolytically-labile hydrazones in peptide amphiphiles were studied as degradable tethers for drug release from nanofiber gels. On-resin addition of the novel compound tri-Bochydrazido adipic acid to a lysine ε-amine allowed for precise placement of a hydrazide in a peptide sequence. Hydrazone formation and hydrolysis were examined by addition and release of nabumetone froma peptide amphiphilematrix.

Delivery of drugs through implantable materials and devices has transformed several areas of medicine, including diabetes treatment, contraception, and cardiovascular repair.1, 2However, increased control over drug release rates and greater biocompatibility and biodegradability of the delivery materials are still necessary improvements. Especially promising new varieties of implantable biomaterials are those made from biodegradable, self-assembling small molecules.3, 4 Not only are such systems more biocompatible compared with traditional polymeric gels, but all components of these systems can also be completely characterized on a molecular scale. Despite their promise as materials, sustained drug delivery from biodegradable, small molecule gels is still an underexplored area in the fields of drug delivery and regenerative medicine.5, 6

Over the past decade, our laboratory has developed and studied peptide amphiphiles (PAs)programmed to self-assemble into high aspect ratio nanofibers.7These PAs are a broad class of molecules that have recently received great attention due to their promise as bioactive materials in regenerative applications ranging from central nervous system regeneration and angiogenesis to bone, cartilage, and enamel regeneration,as well as cancer therapeutics.8-15PAs are synthesized by attaching a hydrophobic tail to a short peptide sequence that includes charged residues to promote solubility and control gelation through electrolyte screening. When the peptide sequence design includes a strong β-sheet forming sequence, PAs can self-assemble into long, filamentous aggregates in aqueous solution.7 These nanostructures are approximately 10 nm in width and up to several microns in length and can be thought of as supramolecular polymers. Charge screening by addition of salts, especially multivalent counterions, or a change in pH induces network formation and gelation at concentrations on the order of 1% by weight.16Previous studies on PA systems have shown the capabilities of PAs to support, signal and deliver cells through the efficient display of a bioactive peptide sequence.9, 17 Here we explore a new method for thedelivery of soluble small molecules from PA gels through the use of hydrolyticallylabile hydrazone tethers. These small molecules may take the form of therapeutic drugs or biological signals.

Control of drug release rate can often be accomplished by covalently attaching a drug to a hydrolytically labile bond, such as a hydrazone, acetal or orthoester.18 Typically, the release rate is governed by the pH of the surrounding media, with faster release observed in acidic (pH 5-6) environments compared with physiological media (pH 7.4). Hydrazone bonds are convenient hydrolytically labile bonds due to the usually facile incorporation of hydrazides into delivery materials.19 However, site-specific incorporation of hydrazides into peptides via solid phase peptide synthesis is still synthetically challenging.

We first attempted on-resin addition of protected hydrazides by the previously reported strategy of adding Boc-NHNHC(O)CH2CH2COOH onto a lysine ε-amine.20, 21 However, we found couplings with this reagent to be very inefficient due undesired intramolecular cyclization reactions, which others have also noted (see Supporting Information for details).22, 23A second attempted strategy was to use (Boc)2NN(Boc)CH2COOH to reveal peptide hydrazines after cleavage, as reported by Melnyk.24Though the synthesis was effective, the resulting peptide hydrazines were found to undergo oxidative decomposition under the reaction conditions required for hydrazone formation. Inspired by Melnyk’s synthesis, we synthesized triply-protected hydrazido acid 4for use in SPPS. It was expected that the carbonyl of the hydrazide would provide more oxidative stability compared with the hydrazine.

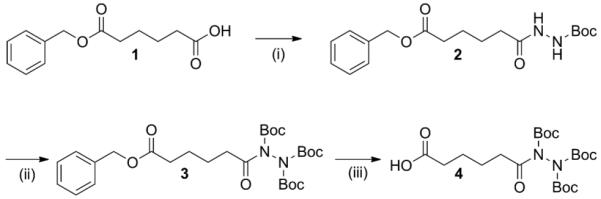

Synthesis of 4 was accomplished in three steps from previously reported adipic acid monobenzyl ester (1) according to Scheme 1. First, tert-butylcarbazate was coupled to 1 using EDC and DPTS, affording monoprotected hydrazide 2 (EDC = N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N’-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride and DPTS = dimethylaminopyridinium p-toluene sulfonate25). Addition of Boc2O to 2 yielded the triprotected derivative, 3. Hydrogenolysis of the benzyl ester with Pd/C furnished triprotected hydrazido acid 4. All reactions showed good to excellent yields, and no chromatography was required (see Supporting Information for full synthetic details and characterization).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of triply-protected hydrazide building block for solid phase peptide synthesis. Reagents and conditions:i) tert-butylcarbazate, EDC, DPTS, CH2Cl2, 2 h, 83%; ii) Boc2O, DMAP, NEt3, CH2Cl2, 2 h, 94%; iii) H2 (1 atm), Pd/C, EtOH, 4 h, 86%.

Applying building block 4 to the synthesis of potentially bioactive materials, hydrazide-containing PA 5 was produced using standard Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis conditions. A free amine was generated on-resin by addition of a Lys(Mtt) residue (Mtt = 4-methyltrityl) with selective removal of the Mtt protecting group using 5% TFA in CH2Cl2. Hydrazino acid 4 was activated using HBTU and DIEA and added on-resin to the exposed lysine ε-amine (HBTU = 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate and DIEA = N,N-diisopropylethylamine). Following cleavage using 95% TFA, PA 5 was purified by HPLC. The unprotected hydrazide was found to be oxidatively stable in air in organic solvents at 40 °C for at least 24 h.

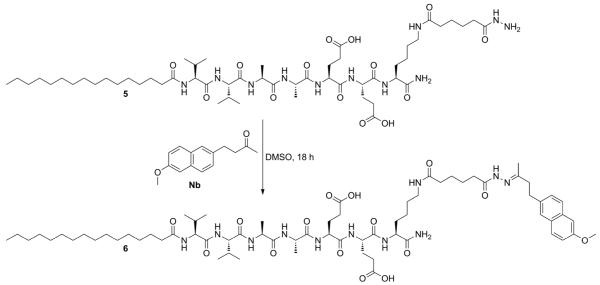

The ketone-containing,non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug nabumetone (4-(6-methoxy-2-naphthyl)-2-butanone) (Nb)was chosen as the model drug to serve as a release probe. Condensation of Nb with PA 5 was carried out in DMSO at room temperature overnight to form hydrazone-containing PA 6, which was purified by HPLC (Scheme 2).Structural characterization of PAs 5 and 6 was then carried out to assess the self-assembly of these novel PAs.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of drug-tethered PA by hydrazone formation.

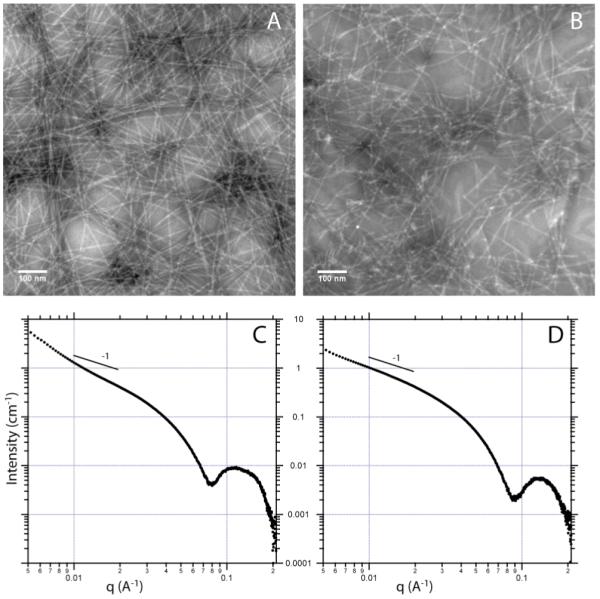

PAs 5 and 6 were characterized in aqueous solution by conventional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) (Figure 1). TEM of PA 5 showed long, cylindrical nanofibers typical ofmany PAs synthesized in our laboratory.26 Some bundling of fibers can be observed in the TEM image.TEM of PA 6showed similar cylindrical nanofibers, though they appeared shorter and less bundled than those of PA 5. SAXS in aqueous solution was used to furtherinvestigate the aggregates formed from PAs 5 and 6. A slope of −1 in the low q region is indicative of cylindrical aggregatesand would be expected;27however, the slight deviation from the −1 slopeobserved in the SAXS curve of PA 6(Figure 1D) is likely a result of a small contribution of bundled aggregates. The even steeper slope in the low q region seen in the PA 5scattering curve(Figure 1C) is consistent with the higher-order aggregates (bundles) seen in the TEM. We attribute the bundling observed in PA 5 to interfiber hydrogen bonding between surface hydrazide groups. Addition ofNb yields a hydrazone that is less capable of hydrogen bonding, which may explain the reduced number of higher-order aggregates observed in PA 6. Excluding the low qregion, the SAXS curves can be reasonably fitted to a polydisperse core-shell cylinder form factor(Supporting Information). The best fit parameters yielded an average fiber diameter of 7.1 nm for PA 5and 7.0 nm for PA 6, supporting TEM results that addition of Nb did not alter fiber dimensions.

Figure 1.

TEM and SAXS of PA 5 (A and C) and PA 6 (B and D).

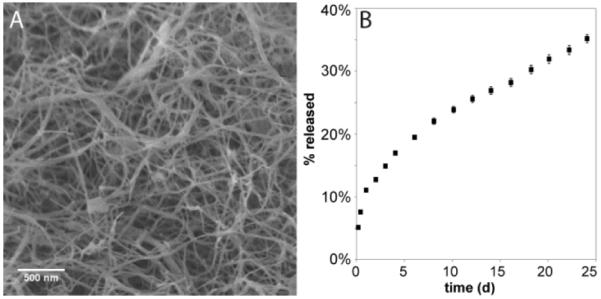

To investigate the release of Nb from PA 6, a mixture of PA6with diluent PA C16V2A2E2 (1:1 w/w, structure shown in Supporting Information) was prepared and gelled with CaCl2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the gel (Figure 2A) shows the expected fibrous morphology. The release kinetics of Nbweremeasured into a sink solution of buffer by monitoring absorbance at 330 nm (Figure 2B).As we are interested in using drug-delivering PA materials as injectable gels for the long-term, sustained delivery of drugs, signals, and cells, we chose to investigate release kinetics at physiological pH.Although hydrazones are often designated as exhibiting high hydrolytic stability at physiological pH, slow hydrolysis is often still observed.28Release was observed over 24 d, with an initial burst release but eventual conversion to a zero-order release profile. We speculate that the burst release may be due to some free Nb in the gel that occurs as a result of sample preparation.

Figure 2.

SEM (A) and release profile (B) of Nb from gel of PA 6 mixed 1:1 with diluent PA into buffer at physiological pH (n=5).

In summary, a small molecule building block (4) for incorporation of hydrazides into peptides has been synthesized. Under standard coupling conditions,4 can be added on-resin to a lysine ε-amine, revealing a free hydrazide upon cleavage from the resin. We demonstrated an application of this chemistry by developing a hydrazide-containing PA, to which a small molecule drug could be tethered via hydrazone formation.Drug tethering was found not to alter the assembly of the PA into filamentous aggregates. The small molecule drug could then be slowly released from the gel into aqueous solution.Further studies on small molecule drug release from PA gels are currently underway in our laboratory. We expect that building block 4 will be useful in several areas of peptide and polymer-based medicine, including peptide-based biomaterials, peptide labeling and polymeric drug conjugation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIDCR, grant No. 2R01DE015920-06 and the NIBIB, grant No. 2R01EB003806-06A2. JBM was supported by a Baxter Early Career Development Award in Bioengineering. We are grateful to the Institute for BioNanotechnology in Medicine (IBNAM) Chemistry Core, the Biological Imaging Facility (BIF), the Integrated Molecular Structure Education and Research Center (IMSERC) and the Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) of the Northwestern University Atomic- and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental Center (NUANCE) for instrument use. NUANCE Center is supported by NSF-NSEC, NSFMRSEC, Keck Foundation, the State of Illinois, and Northwestern University. We acknowledge Dr. Steven Weigand and the DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access Team (DND-CAT) Synchrotron Research Center at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Lab for assistance with SAXS measurements.Use of the APS was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.Matt Webber and Dr. RonitBittonof the authors’ laboratoryare acknowledged for help with SEM and SAXS, respectively.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Full experimental details and characterization data on new compounds, SAXS fittings and aggregate parameters. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Goldberg M, Langer R, Jia XQ. J. Biomater. Sci.-Polym. Ed. 2007;18:241–268. doi: 10.1163/156856207779996931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaVan DA, McGuire T, Langer R. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/nbt876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dankers PYW, Meijer EW. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2007;80:2047–2073. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui HG, Webber MJ, Stupp SI. Biopolymers. 2010;94:1–18. doi: 10.1002/bip.21328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapadia MR, Chow LW, Tsihlis ND, Ahanchi SS, Hrabie JA, Murar J, Martinez J, Popowich DA, Jiang Q, Saavedra JE, Keefer LK, Hulvat JF, Stupp SI, Kibbe MP. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008;47:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branco MC, Pochan DJ, Wagner NJ, Schneider JP. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9527–9534. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webber MJ, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. J. Intern. Med. 2010;267:71–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva GA, Czeisler C, Niece KL, Beniash E, Harrington DA, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Science. 2004;303:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1093783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajangam K, Behanna HA, Hui MJ, Han XQ, Hulvat JF, Lomasney JW, Stupp SI. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2086–2090. doi: 10.1021/nl0613555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webber MJ, Han XQ, Murthy SNP, Rajangam K, Stupp SI, Lomasney JW. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. M. 2010;4:600–610. doi: 10.1002/term.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mata A, Geng YB, Henrikson KJ, Aparicio C, Stock SR, Satcher RL, Stupp SI. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6004–6012. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah RN, Shah NA, Lim MMD, Hsieh C, Nuber G, Stupp SI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:3293–3298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906501107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Z, Newcomb CJ, Bringas P, Jr., Stupp SI, Snead ML. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9202–9211. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Standley SM, Toft DJ, Cheng H, Soukasene S, Chen J, Raja SM, Band V, Band H, Cryns VL, Stupp SI. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3020–3026. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stendahl JC, Rao MS, Guler MO, Stupp SI. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006;16:499–508. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webber MJ, Tongers J, Renault MA, Roncalli JG, Losordo DW, Stupp SI. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ihre HR, De Jesus OLP, Szoka FC, Frechet JMJ. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:443–452. doi: 10.1021/bc010102u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauthier MA, Klok HA. Chem. Commun. 2008:2591–2611. doi: 10.1039/b719689j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao J, Tam JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:3893–3899. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dirksen A, Dirksen S, Hackeng TM, Dawson PE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15602–15603. doi: 10.1021/ja067189k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guy L, Vidal J, Collet A, Amour A, Reboud-Ravaux M. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4833–4843. doi: 10.1021/jm980419o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grandjean C, Gras-Masse H, Melnyk O. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:230–239. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010105)7:1<230::aid-chem230>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonnet D, Grandjean C, Rousselot-Pailley P, Joly P, Bourel-Bonnet L, Santraine V, Gras-Masse H, Melnyk O. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7033–7040. doi: 10.1021/jo0343432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore JS, Stupp SI. Macromolecules. 1990;23:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer LC, Stupp SI. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1674–1684. doi: 10.1021/ar8000926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glatter O, Kratky O. Small Angle X-ray Scattering. Academic Press Inc.; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalia J, Raines RT. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:7523–7526. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.