The secret of good coffee – keep it under wraps

I am sitting at my computer taking sips from a cup of delicious dark-roast black coffee and it seems appropriate that I am writing about green coffee (i.e. dried, unroasted beans), the subject of a paper by Selmar et al. (Braunschweig, Germany, pp. 31–38). The first stage in coffee manufacture is to extract the beans from the flesh of the coffee ‘cherry’; this is done by different methods that result in different flavours in the final product. In wet treatments, the first stage is a mechanical de-pulping followed by immersion in water (‘fermentation’) to remove the remaining pulp. The beans are then dried and the endocarp (‘parchment’) is removed. In semi-dry processing, the fermentation step is omitted; residual pulp and endocarp are removed mechanically after drying. In dry processing, whole cherries are dried and the pulp and endocarp are removed mechanically. In the authors' research, green coffee was treated by these three methods under strictly controlled conditions. For the wet treatment, only half the beans had the endocarp removed. The green coffee beans were stored at 22 °C and 63 % relative humidity for up to 2 years. Viability and germination tests gave very clear results: beans with endocarp retained viability, in some instances for up to 2 years; bare beans lost viability rapidly over the first 4 months. The reason for this was unclear since it seems unlikely that the dried endocarp (parchment) could affect significantly the metabolism of the bean. Distinct biochemical changes such as slow loss of sugars and significant loss of glutamine occurred in all beans and again these changes gave no clue about changes in viability. Sensory tests showed that storage of green coffee caused a distinct loss of aroma within 6 months. Intriguingly, this loss of aroma was slightly less in the beans with retained endocarp; maintenance of viability is thus correlated with an improved retention of quality.

Sink signals source in shaded sugar

Following a small decline in 2000–01, world sugar production has risen steadily to reach 163 million tonnes in 2006–07. About 70 % of this comes from sugar cane (Saccharum spp.), providing a major source of revenue for many less-developed countries. It is thus important to understand more about the factors that influence sucrose synthesis and deposition, as discussed by a South African–Australian group, McCormick et al. (pp. 89–102). They disrupted normal source–sink relationships by reducing the source to just one leaf; all other leaves being shaded. This led to decreased hexose concentrations in the unshaded leaf, while sucrose concentrations were little affected; the reverse was true for culm (the sink tissue). There was a marked increase in photosynthetic efficiency of the unshaded leaf, especially evident in the assimilation rate and the electron transport rate. Then, in a very careful and thorough study, the authors used a reverse northern macroarray to look at gene expression in the unshaded leaf. Of the genes studied, 27 showed changes in expression greater than two-fold; the majority of these were up-regulated. The cohort of up-regulated genes showed a remarkable correlation with the changes in leaf metabolism; for example, expression of PEP carboxylase, representing the C4 phase of photosynthesis, increased by between 2·2- and 4·3-fold in 14 days, while that of the large subunit of Rubisco increased 3-fold over the same period. Such changes were typical of the range of genes involved in photosynthesis. Of the down-regulated genes, the authors note particularly hexokinase (HXK) and fructokinase (FK). Down-regulation of HXK was strongly correlated with the decline in leaf hexose concentration, consistent with a role for HXK as a sensor in hexose signalling. Overall, the results provide clear evidence that an increased carbon demand at the sink (because of decreased supply from the source) leads to signalling, possibly via a hexose-based pathway, thus up-regulating C-fixation via increased photosynthesis in the source leaf.

Rubisco renewed as ravages of age are reversed

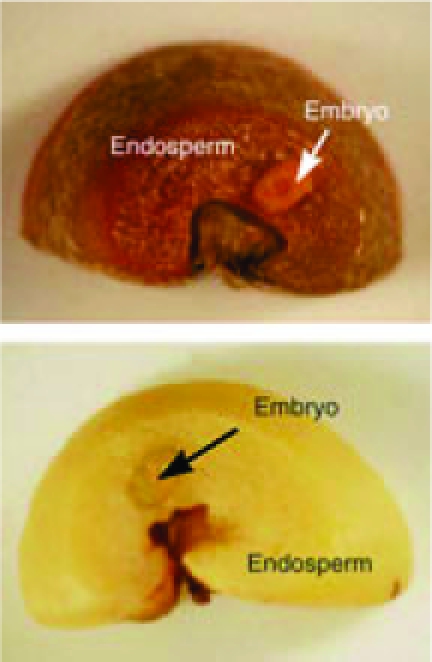

Rubisco is by far the most abundant protein in green leaves. It can comprise 50 % or more of total leaf protein and contain up to 35 % of leaf N. Its synthesis is affected by both light and N supply, and its expression is regulated at both transcriptional and translational levels. In senescing leaves it is an important source of N and C for recycling as synthesis declines and existing protein is broken down. However, it is apparent from the work of Imai et al., Sendai, Japan (pp. 135–144) that the senescence-related loss can be reversed. From their very thorough study we focus on the dynamics of Rubisco synthesis and turnover in leaves of Oryza sativa. Senescence was studied in the 24 days following full leaf expansion. Plants were supplied with 1·0 or 4·0 mm N [supplied as (NH4)2SO4] at intervals. As expected, Rubisco synthesis declined during this time. Transcriptional regulation was evident in the decline of mRNAs encoding both the large and small subunits; there was also regulation at the translational level in that the translational efficiencies of both mRNAs were decreased. This involved both the cytoplasmic and chloroplastic translation systems. However, all these features could be reversed, at least temporarily, by increased N-flux, especially at 4 mm. Thus, as shown by other authors for other aspects of leaf physiology, the senescence programme can be turned around. In the present work, this reversal was especially marked in the most extreme treatment when all tillers and all leaves except for the eighth were removed from plants fed with N at 4 mm. Even at a late stage of senescence, 16 days after full expansion, this treatment led to an increased Rubisco mRNA population (especially of the nuclear-encoded small subunit mRNA) and increased translational efficiency of both mRNAs. This resulted in an increase in Rubisco protein in leaves that had previously been well advanced in senescence.

Small is beautiful when plants are on the pull

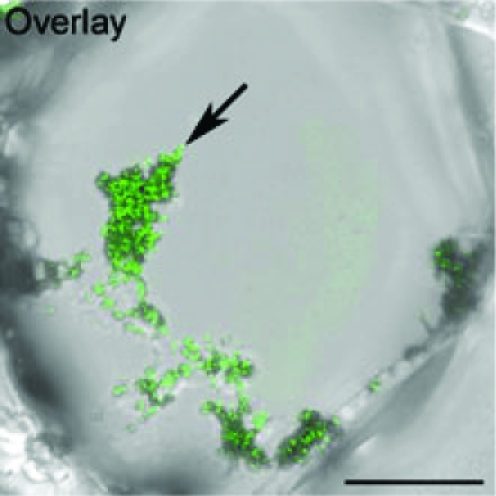

Richard Fleischer's film Fantastic Voyage tells of a surgical team who were miniaturized in order to travel in a tiny submarine through a patient's bloodstream. The purpose of this voyage was to locate and disperse a blood clot in the brain. Although it is impossible to shrink humans, sending therapeutic agents to specific places in the body has become possible through nanotechnology. Tiny particles on a nanometre scale may be directed, for example, to deliver cytotoxic drugs to cancer cells. But what about plants? In the late 1980s, methods were developed for shooting DNA-coated gold or tungsten particles into plant cells, methods now known as biolistics. Questions arise as to whether, in addition to genetic modification via biolistics, nanotechnology has any other applications, including applications with whole plants. The work of a Spanish research team, González-Melendi et al. (pp. 187–195), suggests that the answer may soon be ‘yes’. The authors suspended carbon-coated iron nanoparticles in surfactant solution that was thoroughly mixed into a commercially available succinated gel to give a ‘biocompatible magnetic fluid’. This was injected into the petioles of whole Cucurbita pepo plants, facilitating entry into and transport through the vascular system. Furthermore, the transport could be directed by placing magnets adjacent to parts of the plant. Analysis of plant organs and tissues by microscopy, confocal microscopy and EM showed that the particles became concentrated in relation to the magnetic field. Thus particles accumulated, both inside and outside cells, in regions of the roots and of petioles adjacent to a magnet. The way is therefore opened for the delivery of particular cargoes coated onto the nanoparticles to specific parts of the plant. The use of magnets to generate particle distribution in individual plants is not readily applicable to large crop stands, but certainly could be used with individual plants such as olive and other fruit trees, as suggested by the authors.