Abstract

Background

Sex determining mechanisms are evolutionarily labile and related species often use different primary signals and gene regulatory networks. This is well illustrated by the sex determining cascade of Drosophila fruitflies, which have recruited Sex-lethal as the master switch and cellular memory of sexual identity, a role performed in other insects by the gene transformer. Here we investigate the evolutionary change in the coding sequences of sex determining genes associated with the recruitment of Sex-lethal. We analyze sequences of Sex-lethal itself, its Drosophila paralogue sister-or-Sex-lethal and downstream targets transformer and doublesex.

Results

We find that the recruitment of sister-or-Sex-lethal was associated with a number of adaptive amino acid substitutions, followed by a tightening of purifying selection within the Drosophila clade. Sequences of the paralogue sister-or-Sex-lethal, in contrast, show a signature of rampant positive selection and relaxation of purifying selection. The recruitment of Sex-lethal as top regulator and memory gene is associated with a significant release from purifying selection in transformer throughout the Drosophila clade. In addition, doublesex shows a signature of positive selection and relaxation of purifying selection in the Drosophila clade. A similar pattern is seen in sequences from the sister Tephritidae clade.

Conclusions

The pattern of molecular evolution we observe for Sex-lethal and its paralogue sister-or-Sex-lethal is not characteristic of a duplication followed by neo-functionalization. Rather, evidence suggests a sub-functionalization scenario achieved through the evolution of sophisticated splicing. As expected, we find that transformer evolves under relaxed purifying selection after the recruitment of Sex-lethal in Drosophila. Finally, the observation of doublesex adaptation in both Drosophila and Tephritidae suggests that these changes are due to ongoing adaptation of downstream sex-specific regulation, rather than being associated the recruitment of Sex-lethal and the resulting change in the topology of the sex determining cascade.

Background

Sex determination is the process by which an individual makes the developmental decision to become male or female. Unlike other fundamental processes in development, such as body patterning by Hox genes [1], the molecular mechanisms responsible for sex determination have not been conserved [2]. Instead, a plethora of sex determining strategies exist, varying greatly in the primary signal used in sex determination. This diversity can be seen across the Diptera alone, where the initial signal is genetic in Drosophila melanogaster, environmental in Sciara ocellaris and maternal in Chrysomya rufifacies [3,4, for reviews]. Variation and fast turnover also occur in the genetic implementation of sex determining mechanisms. The housefly Musca domestica provides a striking example for evolutionary lability at this level. In some populations, male development is triggered by the presence of masculinizing alleles with varying genomic location in some populations, whereas in other populations these factors are fixed and sex is based on the presence of a dominant feminizing allele at another locus [5].

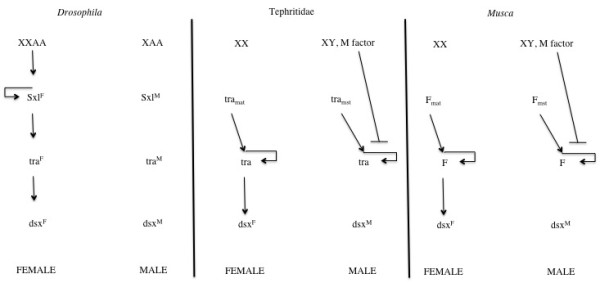

Dipteran sex determination probably provides the best studied model for understanding the evolution of sex determining mechanisms. Particularly well described is the genetic cascade of D. melanogaster, in which sex is determined by a primary signal that is transmitted through a short cascade of regulatory genes and translated into sexual phenotypes via downstream transcription factors (see Figure 1) [6, for a most recent review]. In D. melanogaster, the primary signal is provided by a gene counting mechanism sensing the number of X chromosomes (2 in females, 1 in males). This primary input is translated into differential expression of splice forms of the switch gene Sex-lethal (Sxl). Female embryos express a fully functional SXL protein while males produce a shorter peptide that lacks an RNA-binding domain. The female protein SXLF maintains the master signal through an auto-regulatory self-splicing loop. At the same time, SXLF transmits the female signal further down the cascade by ensuring that transformer (tra) transcripts are spliced into a female-specific, functional, form. The female TRAF protein, in turn, forms a heterodimer with TRA2 protein to regulate the splicing of the transcription factor doublesex (dsx) mRNA. The resulting female variant DSXF regulates female differentiation of somatic tissue. In males, the truncated SXLM has no regulatory effect, leading to the production of an equally inactive default splice variant of tra. The presence of TRAM (i.e., absence of TRAF), results in the production of default male forms of the downstream target dsx, DSXM. tra also regulates the splicing of another transcription factor fruitless. A sex-specific mRNA of this gene is produced in males that contributes to differentiation of male nervous tissue.

Figure 1.

Sex determination networks in flies. A comparison between the sex determination networks in the Drosophila, Tephritidae and Musca domestica (after [3]).

A comparison between the Drosophila sex determining cascade and those of the closely related families Tephritidae and Muscidae (Figure 1) illustrates how sex determining cascades evolved from the bottom up [7]. The downstream genes tra and dsx are used by all three groups. Only Drosophila uses the switch gene Sxl which appears to have been recruited recently to the top of the cascade. The ancestral condition is present in the Tephritidae and Muscidae, which uses tra and a tra-orthologue, respectively, as the switch gene [8-10]. The tra gene in these species maintains its signal through a self-splicing loop operated by the TRA/TRA2 heterodimer. This mechanism is common among the Diptera [8] and might be an ancestral element of the sex determining cascade across the insects [11], as indicated by the discovery in honeybees of a conserved gene with homology to tra [12]. Outside the insects, there is no evidence for tra involvement in sex determination. Homologues of the downstream target dsx, however, have been identified not only in other insects [5,13] but also in worms and mammals [14,15]. This suggests that dsx has been involved in sex determination for a very long time [16].

It is unclear what general principles underlie the bottom-up evolution of sex determining mechanisms or whether indeed such general principles exist [17,18]. However, adaptive scenarios have been proposed that provide plausible adaptive scenarios for the the recruitment of Sxl to the Drosophila cascade [16]. In this paper, we investigate the molecular changes to the Drosophila sex determining cascade due to the recruitment of Sxl. We use sequences from twelve Drosophila species, a sample of species from the Tephritidae, as well as Musca domestica to infer patterns of selection on the coding regions of sex determining genes. Thanks to the detailed molecular knowledge of sex determination in D. melanogaster and the simple structure of the genetic cascade, we are able to formulate clear hypotheses for the consequences of recruitment of Sxl on the molecular evolution of Sxl itself and its downstream targets.

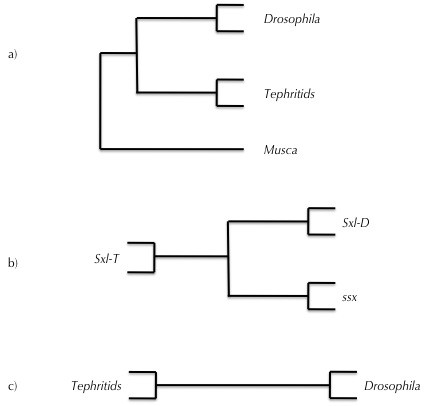

Hypotheses about the patterns of molecular evolution in Drosophila Sxl can be derived from the evolutionary origin of the gene. Evidence suggests that the recruitment of Sxl coincided with a gene duplication event [19,20] that gave rise to Sxl and its paralogue CG3056, now named sister-of-Sex-lethal (ssx) [20]. Both Drosophila genes and their orthologue in the Tephritidae contain two RNA recognition motifs (RRM domains) [[19], see also Figure 2]. Drosophila Sxl encodes an additional N-terminal protein domain, the 'Sxl-specific domain' (Figure 2). Truncated proteins lacking this domain show the same binding affinity as the full Sxl protein, but fail to induce female-specific self-splicing of Sxl transcripts [21]. The presence of the Sxl-specific domain in Drosophila, together with the fact that neither ssx in Drosophila nor the Sxl orthologue in the Tephritidae and Muscidae show sex-specific expression or splicing [19,22-25] suggest neo-functionalization of the Drosophila Sxl duplicate [19]. According to this hypothesis, the common ancestor of Drosophilidae and Tephritidae would have employed a sex determining mechanism similar to that used by the Tephritidae today [16]; following duplication in the Drosophila lineage, Sxl then adapted to its new role in sex determination while the paralogue ssx retained the ancestral, non-sex specific function. Based on this scenario, we would expect a signature of adaptation under positive selection in Drosophila Sxl but comparable levels of purifying selection on tephritid Sxl and Drosophila ssx.

Figure 2.

Structure of Drosophila and tephritid Sex-lethal (Sxl-D and Sxl-T in the Figure) and the Drosophila paralogue ssx. The Figure shows splice variants of Sxl-D, the position of translation start sites (>) and stop codons (*) as well as the position of the Sxl-specific and RRM protein domains following [47]. The gene structure for Sxl-T is for indicative purposes only, as only exonic sequences are available and the exact position of introns is unknown.

A recent study has put forward an alternative scenario for the evolution of Sxl and ssx [20], whereby Sxl would have acquired a new role in sex determination while retaining its ancestral, sex-independent function, whereas ssx would have neo-functionalized to take on roles not previously performed by Sxl. This scenario is based on the observations that loss of ssx had no significant negative effect in fly viability or fertility combined with the discovery of a conserved, non-sex-specific splice variant of Sxl. Under this scenario, we would expect signals of positive selection in both ssx and Drosophila-Sxl, while tephritid Sxl would have evolved under purifying selection.

We also predict an effect of Sxl recruitment on the evolution of the downstream genes in the sex determining cascade. In Drosophila, Sxl took over the memory function previously held by tra. This should have led to evolutionary change at two levels. First, we expect relaxation of selection on amino acids involved in the now obsolete self-splicing of tra. Whether this will result in changes in the tra coding sequence depends on the degree to which the self-splicing mechanism differs from the interaction of TRA/TRA2 with its regulatory targets dsx and fru. The high degree of similarity between TRA/TRA2 binding sites in the intronic sequences of tra outside of Drosophila (the target of self-splicing) [26-28] and in dsx [29] and fru [30] within and outside of Drosophila (the targets of allo-splicing) suggest similar splicing mechanism. The evolutionary loss of tra self-splicing in Drosophila then might not have resulted in changes in its amino acid sequence. However, there is also evidence that the self-splicing mechanism involves a protein complex including not only TRA/TRA2 and RBP1 but also an as yet unknown factor [28, named X-SR]. TRA coding regions involved in the interactions with these proteins would then be free to erode after Sxl recruitment rendered tra self-splicing redundant. Second, we expect adaptive change to accommodate the new splicing regulation of tra through Sxl. As this regulation in Drosophila occurs via the binding of SXL to a non-coding region of tra transcripts, adaptation of tra is expected to have occurred at the level of non-coding (intronic) rather than coding sequences. Adaptive evolution in response to the recruitment of Drosophila Sxl is not expected at the bottom gene of the cascade, as dsx does not directly interact with Sxl and the functional link between tra and dsx is unaffected by Sxl recruitment. If at all, the recruitment of Sxl might have allowed fine-tuning of the sex-specific signal of dsx in Drosophila [16], which would be evident in its relative expression in males and females rather than in changes in the coding sequence.

Results

Molecular evolution of Sxl

We analyzed patterns of molecular evolution by applying phylogenetic maximum likelihood models implemented in PAML [31] to sequence alignments of sex determining genes (see Methods section for details). The mode of selection acting on coding sequences (purifying, neutral or positive) was inferred by estimating the ω = dN/dS ratio that compares the rates of non-synonymous and synonymous mutations. An ω ratio smaller than one indicates that sequences are under purifying selection, where non-synonymous mutations are eliminated from the gene-pool and hence fixed at a lower rate than synonymous mutations; an ω ratio equal to one occurs in neutrally evolving sequences where drift affects synonymous and non-synonymous mutations to the same extent; finally, an ω ratio greater than one occurs in sequences under positive selection, where non-synonymous mutations have a greater chance of reaching fixation than synonymous mutations.

We first inferred selection on Sxl associated with its recruitment to the sex determining pathway of Drosophila by analyzing an alignment of Sxl sequences from the Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and M. domestica (Figure 3a, Additional File 1, Figure S1). Before analyzing evolutionary patterns specifically associated with Sxl recruitment, we tested for global patterns of neutral evolution and positive selection along all branches of the tree (Test 1, see Methods). We detected a proportion of amino acids that evolve neutrally (Table 1, line a), but there was no evidence for the evolution of amino acids under positive selection across all taxa studied (P = 1, Additional File 2, Table S1).

Figure 3.

Illustration of the phylogenetic trees used for analyses of molecular evolution. a) Analyses including sequences from Drosophila Analyses including sequences from Drosophila, the Tephritidae and M. domestica, b) the Tephritidae and a Drosophila paralogue, as used for Sxl and ssx, and c) analyses including sequences from Drosophila and the Tephritidae.

Table 1.

Significant likelihood ratio tests of selection on Sxl in Drosophila, the Tephritidae and M. domestica sequences

| Test | Line | Alternative Ma | Null Ma | 2ΔL | df | Pb | Sitesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | Nearly Neutral | One ratio | 112.53 | 1 | < 0.0001 | 21 |

| 2-D | b | Local selection | Local relaxation | 9.16 | 1 | 0.0024 | 17 |

| 2-T | c | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 262.18 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 1 |

| 2-T | d | Local selection | Local relaxation | 5.46 | 1 | 0.019 | 0 |

| 3-D | e | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 248.25 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 0 |

| 3-Rd | f | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 208.30 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 43 |

a Alternative and null models, see Additional File 2, Table S1 for more information on models and Log-likelihood values, b P value calculated from a χ2 distribution, c number of sites significant in Bayesian post-hoc tests (P < 0.05), d clade consisting of all species excluding Drosophila. The alignment, after deleting gaps, was composed of 298 codons. Tests that we deemed weakly significant because Bayesian post-hoc tests did not detect relevant AA are shown in italics.

We then looked for signatures of selection during Sxl's recruitment to the sex determining cascade. We tested for a signal of relaxed selection on the basal branch leading to the Drosophila clade, i.e., identifying amino acids that evolve neutrally on the basal branch but are under purifying selection on the rest of the tree. This test was significant (P < 0.0001, Additional File 2, Table S1) revealing an evolutionary shift from purifying selection to neutral evolution on the branch leading to the Drosophila clade. Given the signature of relaxed purifying selection, we then tested for the signal of positive selection on the basal Drosophila branch, seeking to identify sites that are under positive selection on that branch but evolve neutrally or are under purifying selection on the rest of the tree. We found significant evidence of positive selection (P = 0.0024, Table 1, line b). Furthermore, posterior Bayesian analysis provided evidence for adaptive fixation of 17 amino acids (with P ≥ 95%) (Table 1, line b). Taken together, these tests indicate that the recruitment of Sxl to the Drosophila sex determining cascade coincided with release from selective constraint and adaptive changes in the protein sequence.

As a comparison, the same tests were applied to assess selection specific to the basal branch of the tephritid clade. The test for positive selection was significant (Table 1, line d), but Bayesian analysis did not identify any site under positive selection (Table 1, line d). The failure to identify selected codons by Bayesian estimation does not provide reliable evidence for positive selection on the branch leading to the Tephritidae. Inconsistent results of this type can occur whenever codons cannot be unambiguously allocated to a particular class of sites (Z. Yang, pers. comm.). Our data therefore provide, at best, weak evidence for positive selection at the root of the Tephritidae, in contrast to strong evidence for positive selection at the root of the Drosophila clade.

The previous tests investigated the selective signatures of substitutions along the branch coinciding with Sxl's recruitment to the sex determining cascade. We also performed tests to investigate patterns of evolutionary change following the recruitment to sex determination. A first test sought to identify sites that are under relaxed selection along all branches of the Drosophila clade but under purifying selection elsewhere in the tree. This test was significant (P < 0.0001, Table 1, line e), but again no individual amino acid was identified by site-specific Bayesian tests. Evidence for relaxed selection of Sxl in the Drosophila clade is therefore inconclusive. In contrast to this, we obtained highly significant results for the mirror model, which identified amino acids that are under purifying selection in Drosophila but evolve neutrally across the rest of the clade. Moreover, Bayesian posterior tests provided robust evidence for relaxation of purifying selection affecting 43 sites (Table 1, line f). Tests for positive selection either along the internal branches of the Drosophila clade or the rest of the tree were non-significant. Together this evidence suggests that the main evolutionary change to Sxl after its recruitment to Drosophila sex determination was a relative strengthening of purifying selection. The absence of recurrent positive adaption within the Drosophila clade indicates that adaptive change of Sxl to its new role in sex determination occurred prior to the divergence of the Drosophila species.

Molecular evolution of the Sxl paralogue ssx

We investigated selection pressures associated with the duplication of Sxl in Drosophila by analysing an alignment including Drosophila Sxl and ssx as well as their orthologue Sxl in the Tephritidae (Figure 3b, Additional File 3, Figure S2). Analysis of selection on specific sites along all branches provided evidence for neutrally evolving sites over the whole tree (Table 2, line a) but the test for tree-wide positive selection was not significant (P = 1, Additional File 4, Table S2). Branch-site models on the branch leading from the Sxl/ssx split to the ssx clade in Drosophila provided evidence for the adaptive fixation of 18 amino acids on the ancestral branch (Table 2, line b). In addition, the test for local relaxation across the ssx clade, rather than the basal branch only, was significant (Table 2, line c) and identified 31 codons that evolve under purifying selection in Sxl, but neutrally in ssx. So we find evidence from two different tests: adaptive fixation of some amino acids on the ancestral branch of ssx (from the first test) which is followed by neutral evolution of some amino acids in the clade (from the second test). Because nine of the 18 amino acids that were inferred by Bayesian analysis to have been positively fixed at the Sxl/ssx split were also found to evolve neutrally once fixed in the ssx clade, they are likely characteristic of Sxl evolution rather than ssx evolution. There remains consistent evidence of nine amino acids fixing under positive selection for ssx. Our results suggest that adaptive evolution following the gene duplication in Drosophila was not restricted to Sxl, as extensive ancestral adaptive evolution was observed for amino acids of the paralogue ssx.

Table 2.

Significant likelihood ratio tests for selection on Drosophila and tephritid Sxl and Drosophila ssx

| Test | Line | Alternative Ma | Null Ma | 2ΔL | df | Pb | Sitesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | Nearly Neutral | One ratio | 189.21 | 1 | < 0.0001 | 24 |

| 2-ssx | b | Local selection | Local relaxation | 7.94 | 1 | 0.019 | 18 |

| 3-ssx | c | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 193.70 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 35 |

a Alternative and null models, see Additional File 4, Table S2 for more information on models and Log-likelihood values, b P value calculated from a χ2 distribution, c number of sites significant in Bayesian post-hoc tests (P < 0.05). The alignment, after deleting gaps, was composed of 265 codons.

Molecular evolution of downstream sex determining genes

We performed analyses designed to detect changes in the pattern of molecular evolution of the downstream sex determining genes tra and dsx, coinciding with the recruitment of Sxl in Drosophila. For tra, we analyzed an alignment of Drosophila and tephritid sequences (Figure 3c, Additional File 5, Figure S3). We found evidence for site-specific neutral evolution (Table 3, line a). The likelihood ratio test for local relaxation on the basal branch (separating the Drosophila clade and the Tephritidae) was significant, but no amino acid was found to have evolved neutrally on that branch (Table 3, line b), so the overall evidence for relaxation on the basal branch alone is weak. Tests of local relaxation of selective constraint were significant for both clades (Table 3, lines c and d). The effect was quantitatively stronger in the Drosophila clade than in the Tephritidae (Additional File 6, Table S3); 16 sites were inferred to evolve neutrally in Drosophila, but only 1 in the Tephritidae. Taken together, these results show that the recruitment of Sxl to the sex determining cascade coincided with a significant loosening of selective constraint in the Drosophila clade.

Table 3.

Significant likelihood ratio tests of selection on transformer in Drosophila and the Tephritidae

| Test | Line | Alternative Ma | Null Ma | 2ΔL | df | Pb | Sitesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | Nearly Neutral | One ratio | 13.75 | 1 | 0.0002 | 4 |

| 2 | b | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 5.39 | 2 | 0.02 | 0 |

| 3-D | c | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 64.89 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 16 |

| 3-T | d | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 15.79 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 1 |

a Alternative and null models, see Additional File 6, Table S3 for more information on models and Log-likelihood values, b P value calculated from a χ2 distribution, c number of sites significant in Bayesian post-hoc tests (P < 0.05). The alignment, after deleting gaps, was composed of 122 codons. Tests that we deemed weakly significant because Bayesian post-hoc tests did not detect relevant AA are shown in italics.

The evidence for a relaxed purifying selection in Drosophila tra is corroborated by the pattern of insertions and deletions (indels) for tra that is not taken into account by PAML's analysis of coding sequences. First, the coding sequence of the tra protein is on average much shorter in Drosophila than in the tephritids (Table 4). Whilst some indels appear to be species-specific, we observe four substantial domains (length greater than 30 nucleotides, with a total of 469 nucleotides) that are conserved in all tephritid species but absent in all Drosophila species (see Additional File 6, Figure S3). These represent indel events that have most likely taken place on the ancestral branch dividing the two clades. The difference in mean coding length between the two clades is 652 nucleotides, so the 469 ancestral indels make up a significant share of this length difference. These important structural changes in the protein provide further evidence for the relaxation of purifying selection on tra coinciding with the recruitment of Sxl in the sex determination network.

Table 4.

Coding sequence (CDS) length and indel rate within the Drosophila and tephritid clades for transformer

| Clade | CDS Length | Indel ratea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Variance | Mean | Variance | |

| Drosophila | 603 | 4412 | 0.409 | 0.397 |

| Tephritids | 1255 | 132 | 0.258 | 0.062 |

| P Value | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.017 | < 0.0001 |

a Indel rate was calculated for each pair of species within a clade by dividing the number of indel sites by the number of nucleotides in the pairwise alignment, then further dividing by the branch length between the two species estimated using the dsx gene.

In addition to a general shortening, we observe much greater variance in the length of the tra protein between Drosophila than between tephritid species (see Table 4). This again suggests weaker purifying selection against indels, or less consistent selection across Drosophila species. The comparison between Drosophila and the Tephritidae is potentially confounded by differences in branch length (i.e., divergence time) between the clades. To control for this effect, pairwise comparisons were made within each clade, and the number of indels per site was scaled by the branch lengths separating each pair of species. Based on these data, we found that the rate of indels is higher in the Drosophila than the tephritid clade (Wilcoxon test, W = 1092, P = 0.017). In addition, the variance in the indel rate was much higher in the Drosophila than the tephritid clade (Bartlett test for homogeneity of variances, K2 = 28.6, P < 0.0001). From a statistical point of view these tests are not entirely rigorous, as they do not take into account the inter-dependence between the data points derived from overlapping pairs of species. However, the large difference observed, in particular in the variance in indel rates, suggests that the evolutionary processes are not identical in the two clades, with lower evolutionary constraint in the Drosophila clade.

We finally analyzed patterns of molecular evolution in the dsx gene. The lower rate of change in dsx allowed us to include the gene sequence from M. domestica in our analysis, without removing an excess of amino acids due to alignment gaps (Figure 3a, Additional File 7, Figure S4). As with Sxl and tra, analyses based on site models revealed that some sites evolve neutrally across the entire tree (Table 5, line a), but there was no evidence for consistent positive selection (P = 1, Additional File 8, Table S4). Including the sequences from M. domestica allowed us to root the split between the Drosophila and tephritid clades.

Table 5.

Significant likelihood ratio tests of selection on doublesex in Drosophila, the Tephritidae and M. domestica

| Test | Line | Alternative Ma | Null Ma | 2ΔL | df | Pb | Sitesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | Nearly Neutral | One ratio | 183.62 | 1 | 0.0001 | 17 |

| 2-D | b | Local selection | Local relaxation | 10.52 | 1 | 0.005 | 6 |

| 2-T | c | Local selection | Local relaxation | 8.34 | 1 | 0.015 | 4 |

| 3-D | d | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 36.64 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 4 |

| 3-Rd | e | Local relaxation | Uniform Selection | 70.17 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 8 |

a Alternative and null models, see Additional File 8, Table S4 for more information on models and Log-likelihood values, b P value calculated from a χ2 distribution, c number of sites significant in Bayesian post-hoc tests (P < 0.05). The alignment, after deleting gaps, was composed of 364 codons.

Applying tests to infer changes in selection on the basal branches leading to the Drosophila and tephritid clades, we detected evidence for positive selection along both branches (Table 5, lines b and c), with 6 and 4 sites being identified as targets in Drosophila and the Tephritidae, respectively. Comparing the evolution of the gene within and outside of Drosophila, we found evidence for relaxation of purifying selection at a small proportion of sites within Drosophila (4 sites, Table 5, line d) and in the outgroup (8 sites in the Tephritidae and M. domestica, Table 5, line e).

Type I error in the inference of positive selection

Although our analyses provide evidence for adaptation at some point in the phylogeny of every gene except tra, caution is required when inferring past selection from DNA sequences. When sequences are very divergent, the occurrence of multiple substitutions at a site (saturation) can cause the rate of synonymous substitutions (dS) to be under-estimated. This, in turn, results in an inflated dN/dS ratio and the inference of spurious positive selection. Problems of this kind are unlikely to affect our results because the MLE methods used here estimate the most likely dN/dS ratio based on patterns of substitutions along all branches of a tree and have been shown to be significantly more powerful and reliable for inferring ancestral positive selection than counting methods comparing pairs of sequences [32-34].

In order to formally rule out effects of saturation on our results, we performed extensive simulations in an approach previously taken by Studer et al. [34, see also Methods]. These simulations seek to estimate the type I error in a conservative scenario. We generated artificial alignments by simulating sequence evolution along the tree of the original sequences using the parameters of the null models (in the absence of positive selection) for all genes. To make the test conservative, the risk of saturation was artificially increased by multiplying the number of substitutions per codon on the tested branch by a factor of 1.5. For each gene, a set of 200 simulated alignments was analyzed for positive selection using the same tests as in the original analyses. The highest rate of false positives observed in our conservative approach was 1% (for Sxl), indicating that our inferences of positive selection are extremely unlikely to be due to type I error.

Discussion

In this paper we investigated the changes in the patterns of molecular evolution evolution of sex determining genes associated with the recruitment of Sxl to the top of the Drosophila sex determining cascade. We analyzed the evolution of Sxl itself, its Drosophila paralogue ssx, and the downstream targets tra and dsx, using sequences from species of Drosophila and their sister clade the Tephritidae, as well as M. domestica.

Drosophila Sxl is thought to have originated through duplication on the branch leading to the Drosophila clade [19,20]. The ancestral function of Sxl, and its current function in the Diptera outside Drosophila are not known to be associated with sex determination [22,24]. Two hypotheses have been put forward as to how new and ancestral functions were shared between the two Drosophila paralogues Sxl and ssx. Traut et al. [19] proposed that Sxl neo-functionalized to its sex determining role whereas the paralogue ssx would have maintained the ancestral functions. Alternatively, Cline et al. [20] suggested Sxl would take on a new sex determining function while simultaneously both Sxl and ssx would sub-functionalize to share non sex-specific functions ancestrally performed by Sxl.

Based on our analyses and including previous findings, it is now possible to weigh up the relative merits of these two evolutionary scenarios. The fact that Sxl has undergone significant changes is not contentious. It is clear that the gene has adapted to its new sex determining role by the addition of a new domain and the evolution of sophisticated RNA splicing. Our analyses have shown that Sxl has undergone adaptive evolution in its coding sequence at a limited number of amino acids, followed by a tightening of purifying selection on the protein sequence. It seems furthermore likely that Sxl has retained an ancestral function, an interpretation that is supported by the fact that one of the Sxl transcripts in Drosophila lacks the Sxl-specific domain and is expressed in both sexes [20]. But in the light of our findings it is now also clear that ssx has undergone adaptive evolution. Thus, we have shown that the gene shows a signature of adaptive change as well as a release from purifying selection on its coding sequence, resulting in a protein that differs significantly from both its paralogue in Drosophila and its orthologue in the Tephritidae. This finding is in line with Cline et al.'s [20] hypothesis of sub-functionalization. Adaptation in both genes could further indicate that the duplication of Sxl allowed for the alleviation of 'adaptive conflict' [35] previously imposed by the double function of the ancestral gene. Establishing whether this is the case, however, will require more detailed information on the non sex-specific functions of Drosophila Sxl and ssx and their orthologue in other dipteran species.

Our analyses were also able to shed some light on the repercussions of Sxl recruitment in the patterns of molecular evolution of genes further down the sex determining cascade. The protein evolution observed in Drosophila tra is characterized by extensive neutral evolution and high rates of indels. These results echo those found by a previous study using a smaller number of species [36]. The evidence for sequence degradation adds to the inferred loss of the putative auto-regulation domain in Drosophila tra [11,28], and corroborates the view that the recruitment of Sxl as the main sex switch gene relieved the pressure of purifying selection on tra. Whether the relaxation of selection on Drosophila tra outside the specific auto-regulatory domain is due to the loss of the sexual memory function is difficult to ascertain. The TRA/TRA2 binding sites in Drosophila dsx and fru are well conserved [26-30], implying that TRA's regulatory function is still required. There are, however, suggestions that the auto-regulation of tra is more complicated than its regulation of dsx [28,37]; rather than forming an enhancing complex with TRA2 as for dsx pre-mRNA, the TRA protein silences expression in tra pre-mRNA. Regions of the protein only involved in these specific auto-regulatory mechanisms would be free to erode after recruitment of Sxl in Drosophila.

There is also the additional (and non-exclusive) possibility that the relaxation of purifying selection on tra sequence is the result of Sxl taking over other sex-specific regulatory functions. Over thirty potential functional binding sites for Sxl have been found in Drosophila [38,39], some of these may have been ancestrally regulated by tra. The loss of these functional links from tra could have relieved it from selection pressure. Since Drosophila Sxl was sex specifically spliced by tra before it was promoted to top regulator in the sex determining cascade [40], there has been a relatively long evolutionary time for Sxl and tra to exchange various functions, potentially selected for their effectiveness of specific target splicing. In that light it would be interesting to compare the putative targets of Sxl in Drosophila with those of tra outside of Drosophila. Overlap between these two sets would support this hypothesis.

Taken together, our results indicate that the adaption of tra to its new regulatory role in somatic sex determination (loss of self-regulation, and potential targets, interaction with Sxl), did not require positively selected amino acid substitutions, but rather the degradation of redundant parts of the protein-coding sequence. This partial erosion was complemented with selective changes elsewhere in the gene sequence. Thus, we observe changes in the non-coding sequence, where we see the emergence and conservation of a Sxl binding site in intronic sequences of Drosophila tra (data not shown).

The evolution of Sxl and tra in Drosophila can be compared with a different change in the top regulator in honeybees. In this group, female development is driven complementary sex determiner (csd), a switch gene specific to the genus Apis. Sex determination in honeybees is haplodiploid, with females heterozygous and males hemizygous at the csd locus. Similar to Drosophila Sxl, csd arose by duplication of feminizer (fem), the ancestral top regulator and orthologue of tra [12,41]. In contrast to Drosophila, where Sxl underwent a short bout of adaptation on its recruitment and tra shows evidence of relaxed selection, csd in honeybees has undergone continued positive selection since its creation by duplication, whereas fem has experienced tightening purifying selection. Presumably, it is the requirement for heterozygosity in females that drives continued change in the amino acid sequence of csd [41]. The strong purifying selection on fem has been attributed to potentially deleterious effects of unspecific protein-protein interactions that could arise from amino acid changes [41]. Our results suggest that such deleterious effects either play a lesser role in Drosophila or are compensated by the benefit of mutations degrading tra functions that have become redundant since the recruitment of Sxl.

We also found evidence for positive selection and relaxed purifying selection in dsx, the transcription factor translating the sex determining signal into sex-specific gene expression and differentiation. This was detected both in the Drosophila and in the Tephritidae (albeit in different amino acids). Furthermore, a preliminary analysis found evidence for positive selection in fruitless (fru), a gene with a similar position to dsx in the sex determining cascade that is directly regulated by tra (data not shown). The evidence for widespread adaptive evolution in the downstream target genes of sex determination in Drosophila is surprising as neither dsx nor fru interact with Sxl and both should therefore be unaffected by the recruitment of Sxl. In the Tephritidae, adaptive change is even more surprising, as it occurs in the absence of any (known) topological change in the sex determining cascade. The results therefore suggest that although dsx is conserved in function and sequence across a large part of the animal tree [42], continuous evolutionary change occurs independent of topological changes in the network. It is unclear what forces might generate positive selection on downstream sex determining genes [16].

Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that the recruitment of Sxl to the Drosophila sex determining cascade has coincided with changes in the evolution of the Sxl gene itself, its paralogue ssx and the downstream genes involved in sex determination, tra, dsx and fru. Studying a well-known and relatively simple gene cascade has enabled us to relate and confront the evolution of a network structure with the direction of selection on the amino acids of the genes participating in that network. Patterns of molecular evolution of amino acids in relation to network changes (or indeed their absence) in Drosophila emerge from our analysis, notably the sub-functionalization of Sxl and ssx, and the degeneration of tra, along with the ongoing evolution of dsx in Drosophila and the Tephritidae. Future experimental work will hopefully shed more light on this issue, notably by investigating the molecular function of Sxl splice forms that are produced equally in both sexes and so may perform one the of the ancestral function of the gene.

Methods

Sequence data

For the genus Drosophila, our analyses were based on the genome sequence and annotation of D. melanogaster [43] and genome assemblies for eleven additional species, D. simulans, D. sechelia, D. yakuba, D. erecta, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, D. persimilis, D. willistoni, D. virilis and D. grimshawi. Starting from the D. melanogaster annotation, we identified orthologous sequences of Sxl, ssx, tra, fru and dsx in the eleven other species by querying their genomic scaffolds with exonic sequences of D. melanogaster using the BLAST program (v8.11.0) [44].

Orthologues of the genes in the Tephritidae were obtained from the NCBI sequence repository. In these searches, we used the female splice variants of Sxl and tra in D. melanogaster and concatenated the early and late variants of Sxl. For dsx, the male and female variants were also concatenated. Using this approach, we obtained orthologues of Sxl from one Ceratitis and one Bactrocera species, and orthologues of tra and dsx from eight Anastrepha, one Ceratitis and three Bactrocera species. The accession numbers of these sequences can be found in Additional File 9, Table S5. For the gene fruitless, alignments of available sequences produced only a moderate number of overlapping sites. This gene was therefore excluded form our analyses.

Sequences were aligned with the Mafft software (v6.624 beta) [45] using the E-INS-i option with default parameters. Exon boundaries were checked for the Drosophila species using the Jalview visualization software (v11) [46] and the DEDB database [47]. Before proceeding with selection analyses, all positions containing indels were removed from the alignment. Complete alignments are provided in the Additional Files accompanying this article (Additional File 1, Figure S1, Additional File 3, Figure S2, Additional File 5, Figure S3 and Additional File 7, Figure S4).

Maximum likelihood tests of positive selection

Estimations of the selection pressure on coding sequences were based on the ω = dN/dS ratio, comparing the rates of non-synonymous and synonymous mutations. We estimated ω ratios using PAML software (v4.4b) [31]. Several different types of maximum likelihood tests of positive selection were performed.

Test 1 aims to detect amino acids that are under positive selection on all branches. It assumes that codons are under identical selection pressures on all branches of the tree (ωT = ωB = ωD for each codon, see Figure 3 for a tree with branch labels). Test 1 is based on the three "sites" models [31]: the "one ratio" model [31] estimates a single ω0 value for all codons, the "nearly neutral" model ("M1a") classifies codons into those under purifying selection (for which it estimates an ω0 < 1) and those evolving neutrally (for which it fixes ω1 = 1), and finally the "positive selection" model ("M2a") adds a third category of codons under positive selection (for which an ω2 > 1 is estimated). Likelihood ratio tests were used to detect relaxation of purifying selection (comparing the likelihood of the nearly neutral model to that of the one-ratio model) and positive selection (comparing the positive selection to the nearly neutral model). These tests compare the difference in likelihood between two nested models (as 2ΔL) to a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of parameters used by the two models compared.

Tests 2 and 3 are based on "branch-site" models [48] and are aimed at detecting differences in the selective pressures that affect particular codons on particular branches of the tree. Test 2 allows us to detect selective pressures on the basal branch between the Drosophila and tephritid clades, coinciding with the recruitment of Sxl to the Drosophila sex determining cascade. It identifies amino acids that either evolve neutrally on the basal branch but are under purifying selection in both the Drosophila and tephritid clades (ωT = ωD < 1, ωB = 1) or those that evolve under positive selection on the basal branch while being under purifying or no selection within the clades (ωT = ωD ≤ 1, ωB > 1). Test 3 detects general changes in the mode of selection following the recruitment of Sxl. It allows us to detect amino acids that are under purifying selection in one clade but evolve neutrally in the rest of the tree, or those that evolve neutrally in one clade but are under positive selection on the rest of the tree. Each of these tests are specified by three models. The null model ("uniform selection") does not include differences between branches and considers two classes of sites, those evolving under purifying selection (ω0 < 1) and those evolving neutrally (ω1 = 1) across the whole tree. This model is identical to the "nearly neutral model" of test 1 ("M1a"). The first alternative model ("local relaxation") assumes relaxed selection on the branch(es) to be tested. It includes a third class of sites that are evolving neutrally (with ω1 = 1) on the tested branch(es) while being under purifying selection (with ω0 < 1) on the remainder of the tree. The second alternative model ("local selection") omits the class of branch-specific neutral evolution of the "local relaxation" model and replaces it by two additional classes in which sites are under positive selection (with ω2 > 1) on the tested branch(es) but are either under purifying selection (with ω0 < 1) or evolve neutrally (with ω1 = 1) on the rest of tree. Again, likelihood ratio tests are used to assess the improvement of fit between increasingly more parameter-rich models. Whenever likelihood ratio tests provided evidence for significant positive selection, a bayesian procedure [48] implemented in PAML was used to identify the individual sites that most likely were the targets of that selection. All tests were performed according to PAML guidance [31].

To check that saturation of synonymous substitutions was not spuriously inflating the dN/dS ratio, we performed a simulation analysis following the approach of [34]. Artificial alignments were produced with EVOLVER [31] under the null model of "local relaxation". All parameters were set at values equal to the maximum likelihood estimates obtained by fitting the "local relaxation" model to the original data, except the length of the tested branch (defined as number of substitutions per codon in EVOLVER) which was multiplied by a factor of 1.5. The resulting alignments were tested for positive selection by applying test 2. The log-likelihood difference (2ΔL) of these tests was recorded. As the sequences were generated in the absence of true positive selection but with longer branch lengths, this procedure provided a null distribution of 2ΔL for sequences with exaggerated divergence against which we tested the value observed in the analysis of the original data. Due to the artificially increased branch lengths in the simulated data, this approach provides an extremely conservative test for positive selection. If the test on the original sequences was prone to type I error due to saturation in the estimated rate of synonymous substitutions, then tests on the even more divergent produced alignments should be even more so, and the original 2ΔL value would be unlikely to fall within the extremes of the null distribution.

Authors' contributions

MR and AP conceived the study, CM performed the analyses, all authors wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Alignment of Sex-lethal of Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and M. domestica. Alignment used for analyses of Sex-lethal including sequences from Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and Musca domestica. The alignment is shown translated into amino acids. Sites under relaxed selection in the Tephritidae and Musca are indicated by a "1" in the line "Clade R ω = 1", those under positive selection on the basal brach leading to Drosophila Sex-lethal are indicated by a "*" in the line "Clade Droso ω > 1". These site-specific results are based on Bayes Empirical Bayes analyses mentioned in the main text. The RRM domains of the protein are also shown.

Table S1. Maximum likelihood models of selection on Sxl in Drosophila, the Tephritidae and M. domestica sequences.

Figure S2. Alignment of Sex-lethal of Drosophila species and the Tephritidae only, and ssx of Drosophila. Alignment used for analyses of Sex-lethal and ssx including sequences from Drosophila species and the Tephritidae. The alignment is shown translated into amino acids. Sites under relaxed selection in ssx (or CG3056) are indicated by a "1" in the line "Clade CG ω = 1", those under positive selection on the basal brach leading to ssx are indicated by a "*" in the line "Clade CG ω > 1". These site-specific results are based on Bayes Empirical Bayes analyses mentioned in the main text. The RRM domains of the protein are also shown.

Table S2. Maximum likelihood ratio models for selection on Drosophila and tephritid Sxl and Drosophila ssx.

Figure S3. Alignment of transformer of Drosophila species and the Tephritidae only. Alignment used for analyses of transformer including sequences from Drosophila species and the Tephritidae. The alignment is shown translated into amino acids. Sites under relaxed selection in the tephritid clade are indicated by a "1" in the line "Clade Teph ω = 1", those under relaxed selection in the Drosophila clade are indicated by a "1" in the line "Clade Droso ω = 1". These site-specific results are based on Bayes Empirical Bayes analyses mentioned in the main text. The domains that are conserved in the Tephritids but absent in Drosophila and longer that 10 AAs are from position 2 to 99, 215 to 249, 295 to 317 and 370 to 380 of A. serpentina.

Table S3. Maximum likelihood models of selection on transformer in Drosophila and the Tephritidae.

Figure S4. Alignment of doublesex of Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and M. domestica. Alignment used for analyses of doublesex including sequences from Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and Musca domestica. The alignment is shown translated into amino acids. Sites under positive selection on the basal brach leading to the tephritid clade are indicated by a "*" in the line "Clade Teph ω > 1", those under positive selection on the basal brach leading to the Drosophila clade are indicated by a "*" in the line "Clade Droso ω > 1". These site-specific results are based on Bayes Empirical Bayes analyses mentioned in the main text. Male- and female-specific domain of the protein are also shown.

Table S4. Maximum likelihood models of selection on doublesex in Drosophila, the Tephritidae and M. domestica.

Table S5. GI Accession numbers for sequences.

Contributor Information

Charles Mullon, Email: c.mullon@ucl.ac.uk.

Andrew Pomiankowski, Email: a.pomiankowski@ucl.ac.uk.

Max Reuter, Email: m.reuter@ucl.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ziheng Yang and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. CM was supported by a CoMPLEX PhD studentship from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, MR by funding from the Natural Environment Research Council (fellowship NE/D009189/1 and grant NE/G019452/1) and AP by grants from the Natural Environment Research Council (NE/G00563X/1) and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/F500351/1).

References

- Lappin TR, Grier DG, Thompson A, Halliday HL. HOX genes: seductive science, mysterious mechanisms. Ulster Med J. 2006;75:23–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin I, Baker BS. The Evolutionary Dynamics of Sex Determination. Science. 1998;281(5385):1990–1994. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez L. Sex-determining mechanisms in insects. Int J Dev Bio. 2008;52(7):837–856. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072396ls. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gempe T, Beye M. Function and evolution of sex determination mechanisms, genes and pathways in insects. Bioessays. 2011;33:52–60. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubendorfer A, Hediger M, Burghardt G, Bopp D. Musca domestica, a window on the evolution of sex-determining mechanisms in insects. Int J Dev Bio. 2002;46:75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salz HK, Erickson JW. Sex determination in Drosophila: The view from the top. Fly. 2010;4:60–70. doi: 10.4161/fly.4.1.11277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins AS. Moving up the hierarchy: a hypothesis on the evolution of a genetic sex determination pathway. BioEssays. 1995;17:71–77. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger M, Burghardt G, Siegenthaler C, Buser N, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Dübendorfer A, Bopp D. Sex determination in Drosophila melanogaster and Musca domestica converges at the level of the terminal regulator doublesex. Dev Genes Evol. 2004;214:29–42. doi: 10.1007/s00427-003-0372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger M, Henggeler C, Meier N, Perez R, Saccone G, Bopp D. Molecular characterization of the key switch F provides a basis for understanding the rapid divergence of the sex-determining pathway in the housefly. Genetics. 2010;184:155–170. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.109249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvemini M, Robertson M, Aronson B, Atkinson P, Polito LC, Saccone G. Ceratitis capitata transformer-2 gene is required to establish and maintain the autoregulation of Cctra, the master gene for female sex determination. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:109–120. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082681ms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst EC, van de Zande L, Beukeboom LW. Insect sex determination: it all evolves around transformer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20(4):376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmann M, Gempe T, Schiøtt M, Nunes-Silva CG, Otte M, Beye M. Evidence for the evolutionary nascence of a novel sex determination pathway in honeybees. Nature. 2008;454(7203):519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature07052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohbayashi F, Suzuki MG, Mita K, Okano K, Shimada T. A homologue of the Drosophila doublesex gene is transcribed into sex-specific mRNA isoforms in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Comp Biochem Physiol., Part B: Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;128:145–158. doi: 10.1016/S1096-4959(00)00304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CS, Murphy MW, O'Sullivan MG, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. Dmrt1, a gene related to worm and fly sexual regulators, is required for mammalian testis differentiation. Gene Dev. 2000;14(20):2587–2595. doi: 10.1101/gad.834100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J. The remarkable ubiquity of DM domain factors as regulators of sexual phenotype: ancestry or aptitude? Genes Dev. 2002;16(18):2322–2326. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomiankowski A, Nothiger R, Wilkins A. The Evolution of the Drosophila Sex-Determination Pathway. Genetics. 2004;166(4):1761–1773. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.4.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins AS. The Evolution of Developmental Pathways. first. Sinauer Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy T, Seymour R, Pomiankowski A. Differential regulation drives plasticity in sex determination gene networks. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:388–400. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traut W, Niimi T, Ikeo K, Sahara K. Phylogeny of the sex-determining gene Sex-lethal in insects. Genome. 2006;49(3):254–262. doi: 10.1139/G05-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline TW, Dorsett M, Sun S, Harrison MM, Dines J, Sefton L, Megna L. Evolution of the Drosophila feminizing switch gene Sex-lethal. Genetics. 2010;186(4):1321–1336. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.121202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp D, Calhoun G, Horabin JI, Samuels M, Schedl P. Sex-specific control of Sex-lethal is a conserved mechanism for sex determination in the genus Drosophila. Development. 1996;122(3):971–982. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone G, Peluso I, Artiaco D, Giordano E, Bopp D, Polito LC. The Ceratitis capitata homologue of the Drosophila sex-determining gene sex-lethal is structurally conserved, but not sex-specifically regulated. Development. 1998;125(8):1495–1500. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos D, Ruiz MF, Sánchez L, Komitopoulou K. Isolation and characterization of the Bactrocera oleae genes orthologous to the sex determining Sex-lethal and doublesex genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Gene. 2005;348(0):111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meise M, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Dubendorfer A, Brunner C, Nothiger R, Bopp D. Sex-lethal, the master sex-determining gene in Drosophila, is not sex-specifically regulated in Musca domestica. Development. 1998;125(8):1487–1494. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrieli P, Falaguerra A, Siciliano P, Gomulski LM, Scolari F, Zacharopoulou A, Franz G, Malacrida AR, Gasperi G. Sex and the single embryo: early deveiopment in the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:10–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pane A, Salvemini M, Delli Bovi P, Polito C, Saccone G. The transformer gene in Ceratitis capitata provides a genetic basis for selecting and remembering the sexual fate. Development. 2002;129(15):3715–3725. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos D, Koukidou M, Savakis C, Komitopoulou K. The transformer gene in Bactrocera oleae: the genetic switch that determines its sex fate. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16(2):221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MF, Milano A, Salvemini M, Eirín-López JM, Perondini ALP, Selivon D, Polito C, Saccone G, Sánchez L. The Gene Transformer of Anastrepha Fruit Flies (Diptera, Tephritidae) and Its Evolution in Insects. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(11):e1239+. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshijima K, Inoue K, Higuchi I, Sakamoto H, Shimura Y. Control of doublesex alternative splicing by transformer and transformer-2 in Drosophila. Science. 1991;252(5007):833–836. doi: 10.1126/science.1902987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs V, Ryner LC, Baker BS. Regulation of sex-specific selection of fruitless 5' splice sites by transformer and transformer-2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:450–458. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Parsch J. Positive Correlation Between Evolutionary Rate and Recombination Rate in Drosophila Genes with Male-Biased Expression. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(10):1945–1947. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, dos Reis M. Statistical Properties of the Branch-Site Test of Positive Selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(3):1217–1228. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer RA, Penel S, Duret L, Robinson-Rechavi M. Pervasive positive selection on duplicated and nonduplicated vertebrate protein coding genes. Genome Res. 2008;18(9):1393–1402. doi: 10.1101/gr.076992.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. The evolution of functionally novel proteins after gene duplication. Proc R Soc A. 1994;256(1346):119–124. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulathinal RJ, Skwarek L, Morton RA, Singh RS. Rapid Evolution of the Sex-Determining Gene, transformer: Structural Diversity and Rate Heterogeneity Among Sibling Species of Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20(3):441–452. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MFF, Sánchez L. Effect of the gene transformer of Anastrepha on the somatic sexual development of Drosophila. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54(4):627–633. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.092917fr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels ME, Bopp D, Colvin RA, Roscigno RF, Garcia-Blanco MA, Schedl P. RNA binding by Sxl proteins in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(7):4975–4990. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robida MD, Rahn A, Singh R. Genome-Wide Identification of Alternatively Spliced mRNA Targets of Specific RNA-Binding Proteins. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(6):e520+. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siera SG, Cline TW. Sexual Back Talk With Evolutionary Implications: Stimulation of the Drosophila Sex-Determination Gene Sex-lethal by Its Target transformer. Genetics. 2008;180(4):1963–1981. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.093898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmann M, Lechner S, Schulte C, Beye M. Origin of a function by tandem gene duplication limits the evolutionary capability of its sister copy. PNAS. 2010;107(30):13378–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005617107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CS, Shamu CE, Shen MM, Seifert KJ, Hirsch B, Hodgkin J, Zarkower D. Evidence for evolutionary conservation of sex-determining genes. Nature. 1998;391(6668):691–695. doi: 10.1038/35618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flybase C. The FlyBase database of the Drosophila Genome Projects and community literature. The FlyBase Consortium. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:85–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Kuma Ki, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(2):511–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clamp M, Cuff J, Searle SM, Barton GJ. The Jalview Java alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(3):426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Wee Tan T, Ranganathan S, Lee BTK, Tan T, Ranganathan S. DEDB: a database of Drosophila melanogaster exons in splicing graph form. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wong WSW, Nielsen R. Bayes Empirical Bayes Inference of Amino Acid Sites Under Positive Selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(4):1107–1118. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Alignment of Sex-lethal of Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and M. domestica. Alignment used for analyses of Sex-lethal including sequences from Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and Musca domestica. The alignment is shown translated into amino acids. Sites under relaxed selection in the Tephritidae and Musca are indicated by a "1" in the line "Clade R ω = 1", those under positive selection on the basal brach leading to Drosophila Sex-lethal are indicated by a "*" in the line "Clade Droso ω > 1". These site-specific results are based on Bayes Empirical Bayes analyses mentioned in the main text. The RRM domains of the protein are also shown.

Table S1. Maximum likelihood models of selection on Sxl in Drosophila, the Tephritidae and M. domestica sequences.

Figure S2. Alignment of Sex-lethal of Drosophila species and the Tephritidae only, and ssx of Drosophila. Alignment used for analyses of Sex-lethal and ssx including sequences from Drosophila species and the Tephritidae. The alignment is shown translated into amino acids. Sites under relaxed selection in ssx (or CG3056) are indicated by a "1" in the line "Clade CG ω = 1", those under positive selection on the basal brach leading to ssx are indicated by a "*" in the line "Clade CG ω > 1". These site-specific results are based on Bayes Empirical Bayes analyses mentioned in the main text. The RRM domains of the protein are also shown.

Table S2. Maximum likelihood ratio models for selection on Drosophila and tephritid Sxl and Drosophila ssx.

Figure S3. Alignment of transformer of Drosophila species and the Tephritidae only. Alignment used for analyses of transformer including sequences from Drosophila species and the Tephritidae. The alignment is shown translated into amino acids. Sites under relaxed selection in the tephritid clade are indicated by a "1" in the line "Clade Teph ω = 1", those under relaxed selection in the Drosophila clade are indicated by a "1" in the line "Clade Droso ω = 1". These site-specific results are based on Bayes Empirical Bayes analyses mentioned in the main text. The domains that are conserved in the Tephritids but absent in Drosophila and longer that 10 AAs are from position 2 to 99, 215 to 249, 295 to 317 and 370 to 380 of A. serpentina.

Table S3. Maximum likelihood models of selection on transformer in Drosophila and the Tephritidae.

Figure S4. Alignment of doublesex of Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and M. domestica. Alignment used for analyses of doublesex including sequences from Drosophila species, the Tephritidae and Musca domestica. The alignment is shown translated into amino acids. Sites under positive selection on the basal brach leading to the tephritid clade are indicated by a "*" in the line "Clade Teph ω > 1", those under positive selection on the basal brach leading to the Drosophila clade are indicated by a "*" in the line "Clade Droso ω > 1". These site-specific results are based on Bayes Empirical Bayes analyses mentioned in the main text. Male- and female-specific domain of the protein are also shown.

Table S4. Maximum likelihood models of selection on doublesex in Drosophila, the Tephritidae and M. domestica.

Table S5. GI Accession numbers for sequences.