Abstract

The medial septum (MS) of the basal forebrain contains cholinergic neurons that project to the hippocampus, support cognitive function, and are implicated in age-related cognitive decline. Hypothalamic orexin/hypocretin neurons innervate and modulate basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and provide direct inputs to the hippocampus. However, the precise role of orexin in modulating hippocampal cholinergic transmission—and how these interactions are altered in aging—is unknown. Here, orexin A was administered to CA1 and the MS of young (3–4 months) and aged (27–29 months) Fisher 344/Brown Norway rats, and hippocampal acetylcholine efflux was analyzed by in vivo microdialysis. At both infusion sites orexin A dose-dependently increased hippocampal acetylcholine in young, but not aged rats. Moreover, immunohistochemical characterization of the MS revealed no change in cholinergic cell bodies in aged animals, but a significant decrease in orexin fiber innervation to cholinergic cells. These findings indicate that: 1) Orexin A modulates hippocampal cholinergic neurotransmission directly and transsynaptically in young animals, 2) Aged animals are unresponsive to orexin A, and, 3) Aged animals undergo an intrinsic reduction in orexin innervation to cholinergic cells within the MS. Alterations in orexin regulation of septo-hippocampal cholinergic activity may contribute to age-related dysfunctions in arousal, learning and memory.

Keywords: CA1, microdialysis, basal forebrain, acetylcholine, medial septum

Introduction

The hippocampus plays a crucial role in many types of learning and memory that decline with age (Rosenzweig and Barnes, 2003). Cholinergic basal forebrain neurons located in the medial septum (MS) are an important extrinsic source of neuromodulatory inputs that support hippocampal cognitive function and are implicated in age-related cognitive decline (Gallagher and Nicolle, 1993; Sherman et al., 1981). However, the literature from animal models does not support a consistent association between aging, per se, and loss of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, suggesting that age-related alterations in hippocampal ACh-mediated cognitive processes may reflect dysregulation of cholinergic signaling, rather than frank neuronal degeneration(Decker, 1987; Mesulam et al., 1987).

It has been long known that the basal forebrain receives a substantial input from the lateral hypothalamus (Cullinan and Zaborszky, 1991; Zaborszky and Cullinan, 1989). However, the phenotype of hypothalamic projections to the basal forebrain cholinergic system (BFCS) and the conditions under which these inputs are functionally or pathologically significant are not fully understood. Recently, it has become clear that a substantial portion of hypothalamic projections to the basal forebrain derives from orexin/hypocretin neurons (Espana et al., 2005; Fadel et al., 2005a). These neuropeptides (hereafter referred to as orexins for simplicity) derive from neurons localized exclusively in a contiguous band spanning the lateral hypothalamus, perifornical region and dorsomedial hypothalamus (de Lecea et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 1998). Although limited in number, orexin neurons project to a diverse array of central nervous system targets that support putative roles for these peptides in homeostatic phenomena including sleep, feeding and reward (Aston-Jones et al., 2009; de Lecea et al., 2002; Sakurai, 2005). Orexins increase the firing rate of BFCS neurons, increase cortical ACh release (Arrigoni et al., 2010; Eggermann et al., 2001; Fadel and Frederick-Duus, 2008; Fadel et al., 2005a) and appear to be required for certain cholinergically-mediated cognitive tasks (Boschen et al., 2009; Frederick-Duus et al., 2007). A rapidly-accumulating body of evidence suggests that aging is associated with loss of orexin neurons and other markers of orexin function (Kessler et al., 2011; Kotz et al., 2005; Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 2004; Sawai et al., 2010b; Terao et al., 2002), suggesting that changes in orexin transmission may underlie age-related alterations in septo-hippocampal cholinergic functions. However, the normal role of orexins in modulating hippocampal ACh release and the effect of age on this phenomenon have not been reported.

Here, we used in vivo microdialysis to directly test the effects of MS or hippocampal orexin administration on hippocampal ACh release in young and aged rats. We also employed anatomical approaches to further test the hypothesis that aging is associated with alterations in orexin regulation of the BFCS.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal care and use procedures were carried out in accordance with protocols written under the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Carolina. Seventeen young (3–5 month) and 19 aged (26–30 month) male, Fisher 344 Brown Norway F1 hybrid rats (National Institute of Aging breeding colony; Baltimore, MD, USA ) were fed standard rat chow ad libitum and kept at a 12:12 light-dark cycle in a climate controlled facility. All in vivo experiments were conducted during the light cycle.

In vivo microdialysis

Under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (60–70 mg/kg, ip) all rats received unilateral implantation of guide cannulae (Bioanalytical Systems, Inc. (BAS); West Lafayette, IN, USA) in the caudal hippocampus in the following coordinates relative to Bregma: Young – anterior −5.2 mm, lateral +3.8 mm at 10° angle, ventral −3.6 mm; Aged – anterior −5.6 mm, lateral +4.0 mm at 10° angle, ventral −3.8 mm. A subset of rats received a second guide cannulae in the MS at the following coordinates relative to Bregma: Young, – anterior +0.2 mm, lateral +1.0 mm at 8° angle, ventral −5.5 mm; Aged, – anterior +0.2 mm, lateral +1.0 mm at 8° angle, ventral −5.6 mm. The guide cannula apparatus was held in place by dental cement and 2–3 small stainless steel jewelers’ screws. All animals received buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg, sc) following surgery to minimize post-operative pain. After a two day recovery period following stereotaxic surgery, rats were habituated to the microdialysis bowls for three consecutive days prior to the first day of microdialysis. On the morning of each dialysis session, stylets were removed and replaced with probes (BAS, 30kDa cutoff) extending 2 mm beyond the ventral tip of guide cannulas. Probes were continuously perfused at 2 µl/min with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; [in mM] NaCl 150, KCl 3.0, CaCl2 1.7, MgCl2 0.9, d-glucose 4.9, pH 6.9). Neostigmine (50 nM) was included in hippocampal aCSF to prevent the degradation of ACh as previously described (Fadel et al., 2005b). Microdialysate collection consisted of 11 collections in 15 minute intervals, beginning 3 hr after probe insertion. Cortical and hippocampal ACh release at this time point is stable virtually entirely depolarization-dependent (Bianchi et al., 2003; Moore et al., 1995). During collections 5 through 8 the microdialysis inlet line in either the MS or hippocampus was switched to an aCSF solution containing either vehicle (aCSF), low orexin A (OxA; 0.1 µM; Bachem Americas, Inc.; Torrance, CA; product No. H-4172) or high OxA (10 µM). These concentrations, administered into the basal forebrain via reverse microdialysis, have previously been shown to dose-dependently increase prefrontal cortical ACh efflux (Fadel et al., 2005a). Each animal was tested under all three conditions. Dialysates were stored at −80°C until analysis for ACh could be carried out by liquid chromatography. At the conclusion of dialysis sessions animals were sacrificed, and brains were removed. Probe placement was assessed using an acetylcholinesterase background stain. Animals with probe tracts outside of the target region were excluded from results.

Microdialysis samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Ten µl of each dialysate was injected into a liquid chromatographic instrument where ACh and choline were separated on a microbore analytical column (‘Unijet’ 530 × 1 mm; MF-8904; BAS) using a mobile phase (pH 8.5) containing 45 mM NaH2PO4. A post-column immobilized enzyme reactor containing covalently bound AChE and choline oxidase generated stoichiometric quantities of hydrogen peroxide, which were detected by a “peroxidase wired” glassy carbon electrode (Fadel et al., 2001; Huang et al., 1995). Chromatographic peaks corresponding to ACh were quantitated by comparison with a daily three-point standard curve encompassing the range of ACh dialysate concentrations. Values were then expressed as percent baseline to account for variability in basal efflux across sessions and between subjects. Microdialysis data were uncorrected for probe recovery.

Immunohistochemistry

All tissue was processed according to previously described protocols (Frederick-Duus et al., 2007; Reznikov et al., 2008). Briefly, a separate group of rats unaffiliated with OxA infusion studies were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane and transcardially perfused with 0.1M phosphate buffered saline and 4% paraformaldehyde. Whole brains were removed and post fixed overnight followed by cryoprotection in a 30% sucrose/0.1 M phosphate buffer solution. Tissue was coronally sectioned (45 µm thickness) on a cryostat using a 1:5 serial sectioning method (yielding 5 sets of tissue with adjacent sections 225 µm apart).

Free floating medial septum (MS) or hippocampal sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-OxA antibody (1:1000; Calbiochem; Darmstadt, Germany; product No. PC 362) for 24 hours at room temperature (RT). This step was followed by incubation in biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit secondary (Jackson ImmunoReasearch Inc.; product No. 7111-065-152) for 1.5 hours at RT, and horseradish peroxidase conjugated streptavidin (1:1,600; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.; product No. 016-030-084) for 1 hour at RT. Immunoreactivity was developed using nickel sulfate-cobalt chloride intensified diaminobenzidine with hydrogen peroxide, yielding blue-black immunopositive fibers. Tissue was then incubated in goat anti-choline acetyltransferase (ChAT; 1:3000; Chemicon Int.; Temecula, CA; product No. AB144) primary antibody overnight at RT. Following overnight incubation tissue was incubated in unlabeled donkey anti-goat secondary (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc.; product No. 705-005-003; 2 hrs RT) and goat peroxidase anti peroxidase (1:500; Covance; Berkeley, CA; product No. SMI-4020L; 1.5 hrs RT). Nickel-cobalt was omitted from the development step to yield brown cytoplasmic staining in ChAT+ cells.

Specificity of the antibodies used in the immunohistochemistry experiments was verified by the absence of staining when either the primary or secondary antibody was omitted. More importantly, the anatomical distribution and morphology of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and hypothalamic orexin neurons has been well-characterized. The pattern of cellular labeling produced by the OxA antibody was restricted to a band of cells extending from the lateral hypothalamus proper, arching over the fornix and into the dorsomedial hypothalamus. In forebrain sections, the ChAT antibody used in the current study labeled magnocellular somata distributed among the classically-described regions of the cholinergic basal forebrain (e.g. medial septum; diagonal band of Broca; nucleus basalis magnocellularis) and interneurons in the dorsal and ventral striatum. Collectively, these patterns correlate with those previously reported for cholinergic and orexin neurons in the rodent brain (Broberger et al., 1998; Mesulam et al., 1983).

Cell counts

Using Neurolucida software (MicroBrightField Inc.; Williston, VT), MS neurons and appositions were confined to an approximately 5 mm2 area and counted in 3 serial sections [approximately 9.7−9.2 mm caudal to Bregma (Paxinos and Watson, 1998)] at 20× magnification. Results were averaged to form a representative sample of all cell bodies and appositions within the region. Appositions were counted by randomly selecting 10 ChAT neurons positively labeled for the brown cytoplasmic stain at 10× magnification and refocusing at 40× to count apparent appositions of OxA fibers onto selected cells. A point was counted as an apparent apposition if the overlapping brown cytoplasmic stain and black fiber labeling were in the same plane of focus.

Statistical analysis

All cell counts were analyzed using an independent samples t-test for significant main effects. The in vivo microdialysis data were expressed as a percentage of mean baseline values for each animal. For area-under-the-curve analysis, the cumulative percent change from baseline over collections 5–11 was calculated for each animal and then averaged for individuals of the same age category to derive group means. Although OxA infusion was terminated after the 8th collection, the last three collections were included in this analysis because the orexin response was often delayed and persisted during the post-OxA period. Basal ACh efflux was defined as the mean raw value (pmol ACh/µl dialysate) of the four baseline collections for each animal. Data were analyzed using a DOSE × TIME repeated measures ANOVA with AGE as a between-subjects factor, followed by planned comparisons consisting of modified Bonferroni comparisons (Fadel et al., 2001) to determine the source of significant main effects or interactions. Significant main effects were defined by P < 0.05 and all statistical analysis was performed in SPSS for windows (V.17.0, SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL).

Results

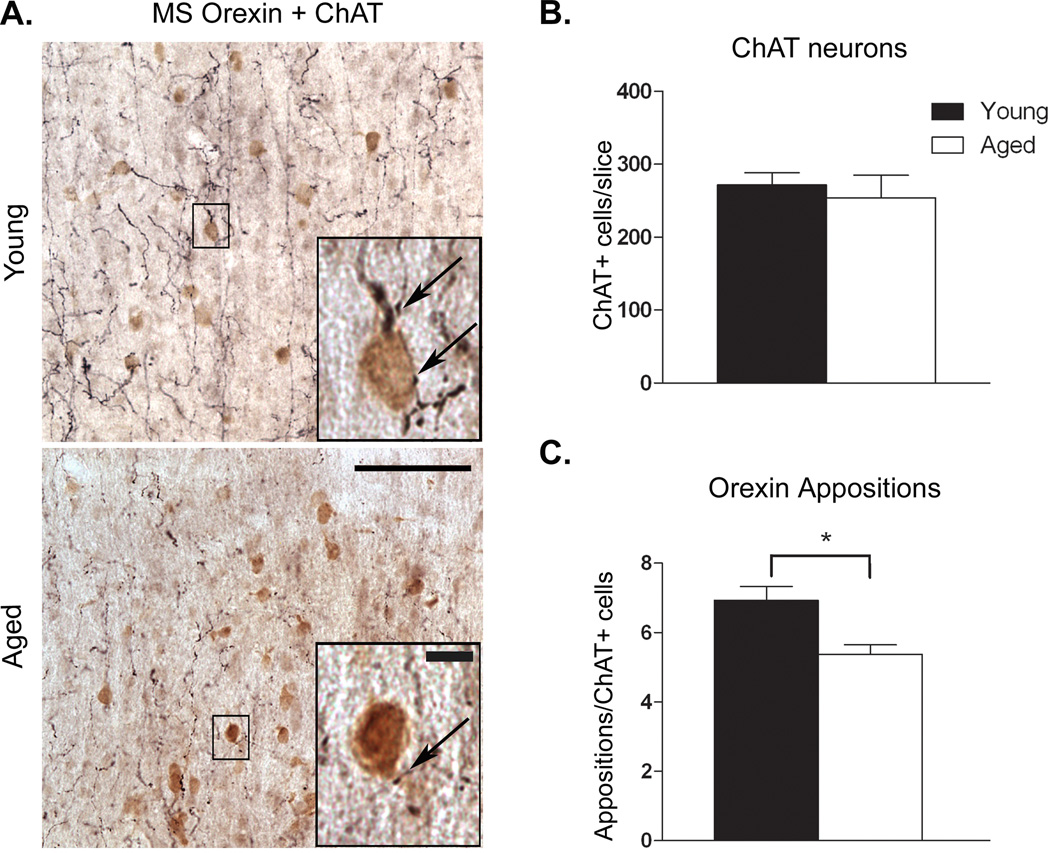

Orexin innervation of the MS is decreased in aging

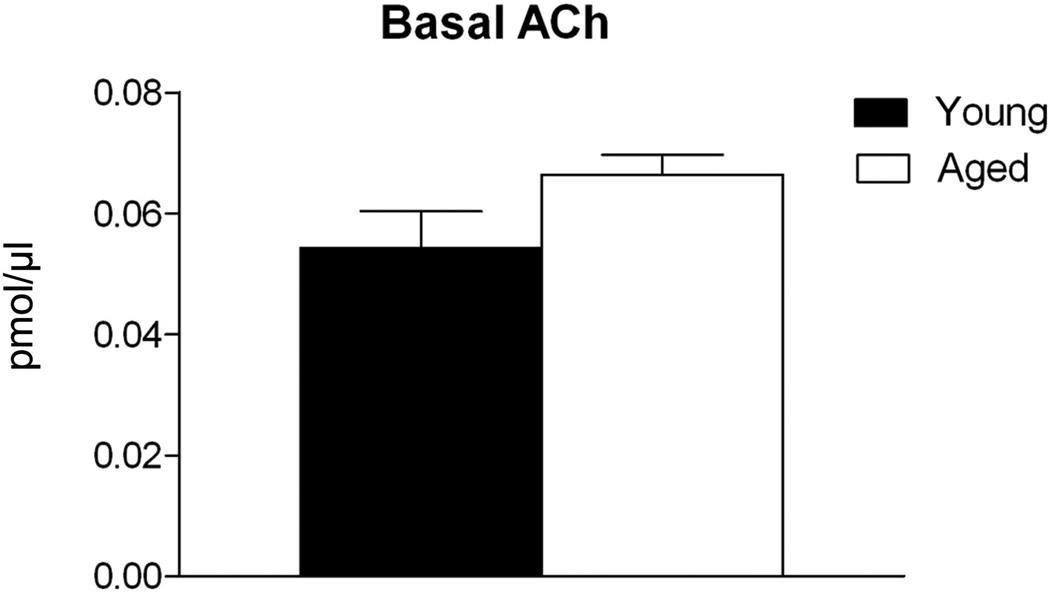

In young animals the MS receives a robust innervation from coarse orexin fibers containing numerous varicosities, including on and around ChAT+ cells (Fig. 1A). Aging was associated with a significant loss of orexin innervation of MS cholinergic neurons, as demonstrated by an approximately 30% reduction in OxA appositions on ChAT+ cells (t8 = 3.191; P = 0.013; Fig. 1B). Analysis of the ChAT+ cells in the MS indicated no change in immunoreactivity in aged rats (Fig. 1C). Despite this difference in orexin innervations, we did not observe an age-related deficit in basal hippocampal ACh efflux. Young animals exhibited basal ACh values of 0.0543 ± 0.0061 pmol/10 µl, compared to 0.0665 ± 0.0032 pmol/10 µl ACh seen in aged rats (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Reduced orexin innervation of cholinergic cells in the MS.

A.) Double labeled immunohistochemistry for orexin fiber innervation (black fibers) of ChAT+ (brown cells) in the MS from young (top) and aged (bottom) rats. B.) Aging did not affect the number of ChAT+ cells in the MS. Numbers represent the mean (±SEM) of the number of neurons counted at three levels of the MS in young and old rats. C.) Points of apparent appositional contacts between orexin fibers or varicosities and ChAT+ somata or proximal dendrites (black arrows in panel A) were significantly reduced in aged rats. Numbers represent the mean (±SEM) of the number of appositions per cholinergic neuron in the MS in young and old rats. Photomicrographs taken at 20×, scale bar = approximately 100 µm. Insets for panel A.) Representative ChAT+ neurons with arrows indicating points of apparent appositional contact. Inset images taken at 40×, scale bar = approximately 10 µm. *P < 0.05, n = 5 young, 4 aged.

Figure 2. Basal ACh efflux in CA1 was not changed by aging.

Neurochemical assessment of hippocampal ACh yielded no significant change in basal efflux in aged rats (white bar) compared to young rats (black bar). n = 17 young, 19 aged.

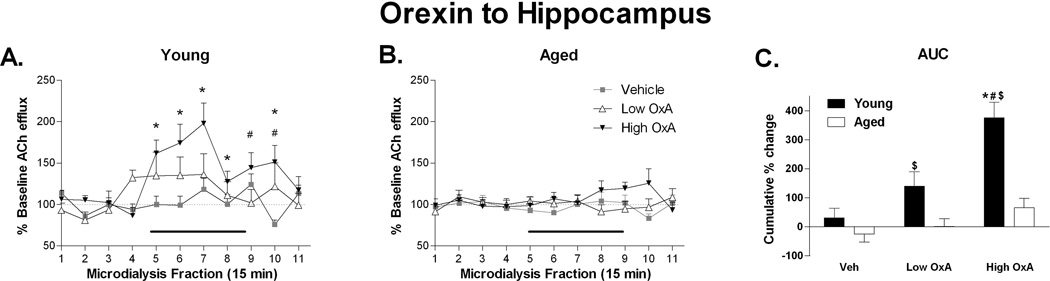

Local infusion of OxA increases ACh in CA1 of young but not aged rats

To test the direct effects of exogenous OxA on hippocampal ACh efflux vehicle (aCSF), low (0.1 µM), or high (10 µM) OxA was infused to CA1 through reverse dialysis during collection intervals 5–8. Young rats displayed a dose dependent increase in hippocampal ACh efflux with a significant DOSE × TIME effect (F(20,160) = 2.043; P = 0.008), which was absent in aged animals (Fig. 3A,B). From the onset of OxA infusion at microdialysis fraction 5, young animals observed significant increases in ACh efflux compared to vehicle infusion through collection 7, and again at collections 9 and 10 (t8 ≥ 2.343; P ≤ 0.047) until returning to baseline values at collection 11. Moreover, comparison of ACh efflux at all three doses in young compared to aged animals revealed a DOSE × TIME interaction (F(20,360) = 2.567; P ≤ 0.0001) with a main effect of age (F(1,18) = 7.295; P = 0.015). Specifically, young rats exceeded baseline efflux by approximately 50–100% during high OxA infusion at microdialysis fractions 5–7 (t18 ≥ 3.06; P ≤ 0.007) while aged animals remained unaffected. Furthermore, the cumulative effects of OxA infusion on hippocampal ACh efflux, assessed in an area-under-the-curve analysis, revealed that both doses of OxA produced greater effects in young animals than old animals, and neither dose increased ACh efflux (relative to vehicle) in the aged group (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Orexin A to the hippocampus increases ACh efflux in young, but not aged rats.

A.) In young rats, administration of OxA into hippocampal area CA1 via reverse dialysis during collection intervals 5–8 (indicated by the black bar) dose-dependently increased ACh release to a maximum of nearly 200% of basal values. At the highest (10 µM) dose, this increase persisted beyond the termination of OxA administration. (B.) Aged rats did not show a hippocampal cholinergic response to local administration of OxA during collection intervals 5–8. C.) Area-under-the-curve (AUC) analysis of the cumulative change in ACh efflux over collections 5–11 further indicated a robust effect of hippocampal OxA administration on local ACh efflux in young, but not aged, rats. * P < 0.05 compared to vehicle, # P < 0.05 compared to low OxA, $ P < 0.05 compared to aged; n = 9 young, 11 aged.

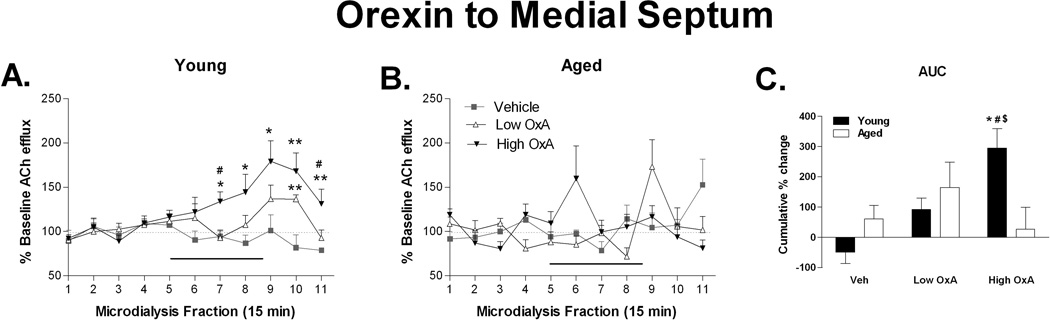

MS infusion of OxA increases ACh in CA1 of young but not aged rats

Given the substantial innervation of the basal forebrain by orexin, OxA may also modulate hippocampal ACh efflux transsynaptically (i.e., via the MS); therefore, OxA was administered to the MS during hippocampal microdialysis sampling (Fig. 4). In young animals, MS infusion of OxA dose dependently increased hippocampal ACh (F(20, 140) = 2.063; P = 0.008). Analysis of aged animals showed a similar DOSE × TIME interaction following OxA infusion (F(20, 140) = 2.871; P ≤ 0.0001) but post hoc analysis failed to reveal the source of significance in the in the ANOVA, as no post-OxA time points were significantly different from baseline or vehicle. In young animals, OxA-mediated increases in ACh efflux were observed starting at microdialysis fraction 7 and continuing until collection 10 (t7 ≥ 2.42; P ≤ .046) before returning near baseline levels. Similar to direct hippocampal infusion, comparison between young and aged rats revealed a significant DOSE × TIME × AGE interaction (F(20, 280) = 2.911; P < 0.0001). The biggest effect of age in MS infusion of OxA was seen in the higher dose, when a delayed reaction to MS OxA, starting at microdialysis fraction 9 and extending throughout the remainder of the dialysis session, was observed in young, but not aged, rats (Fig. 4A,B; t14 ≥ 2.391; P ≤ 0.031). This was further demonstrated by assessment of the cumulative response to the 10 µM dose, where the young group showed robust significant increases relative to both the vehicle condition and the aged group (Fig. 4C). The 0.1 µM OxA dose also revealed a divergence in ACh efflux in between age groups at microdialysis fraction 8 (t14 = 2.34; P = 0.035) when aged animals displayed an apparent depression of hippocampal ACh while young animals were slightly elevated.

Figure 4. Orexin A to the MS increases hippocampal ACh efflux in young, but not aged rats.

A.) In young rats, administration of OxA into the MS via reverse dialysis during collection intervals 5–8 (indicated by the black bar) dose-dependently increased ACh release to a maximum of nearly 180% of basal values. At both the high (10 µM) and low (0.1 µM) doses, this increase persisted beyond the termination of OxA administration. (B.) Aged rats did not show a hippocampal cholinergic response to MS administration of OxA during collection intervals 5–8. C.) Area-under-the-curve (AUC) analysis of the cumulative change in ACh efflux over collections 5–11 revealed a robust effect of the high dose of OxA on hippocampal ACh efflux in young, but not aged, rats. * P < 0.05 compared to vehicle, # P < 0.05 compared to low OxA, $ P < 0.05 compared to aged; n = 8 young, 8 aged.

Discussion

Our studies indicate that aging is associated with a reduction in orexin innervation of medial septal cholinergic neurons. Furthermore, the substantial increase in hippocampal ACh efflux produced by local or MS administration of exogenous OxA in young animals could not be reproduced in aged rats. Collectively, these data point to loss of orexin signaling as a potential source of age-related dysregulation of hippocampal ACh release.

Aging and static measures of orexin and cholinergic function

Recent accounts of orexin immunoreactivity over the aging spectrum have indicated a significant decline in orexin cell bodies in the lateral hypothalamus (Brownell and Conti, 2010; Sawai et al., 2010a) and fibers in the basal forebrain (Zhang et al., 2005). Our own recent work in animals of the same strain and age as those used in the current study showed an age-related loss of more than 40% of orexin neurons (Kessler et al., 2011). The loss of orexin appositions on MS cholinergic neurons reported here, while still significant, was quantitatively less robust than the cell loss, suggesting some degree of compensatory sprouting. Collectively, however, our findings corroborate these previous studies showing age-related decreases in markers of orexin function and further suggest that decreased orexin drive may contribute to decreases in cholinergic activity.

We did not observe any age-related loss of MS cholinergic neurons, nor did our old animals show decreased basal levels of hippocampal ACh efflux. Due to the potential for age-related differences in extraction fraction or sensitivity to cholinesterase inhibitors, a more exacting assessment of basal release such as that provided by ‘no-net flux’ microdialysis would be required to definitively demonstrate that aged animals do not have reductions in basal hippocampal ACh levels. However, our findings are consistent with previous reports that aging, per se, is not associated with substantial alterations in static presynaptic markers of basal forebrain cholinergic function such as ChAT expression or ACh efflux ( (Decker, 1987; Lippa et al., 1980; Sherman et al., 1981) but see(Wu et al., 1988) ). The apparent lack of effect on basal ACh efflux further indicates that orexin inputs to MS do not play a significant role in maintaining tonic levels of cholinergic output, but may be recruited in the arousal or attentional response to salient stimuli, such as those related to homeostatic drives. This hypothesis derives, in part, from the observation that basal cortical ACh efflux is unaltered in rats following orexin lesions, but the cholinergic response to an appetitive stimulus is impaired (Frederick-Duus et al., 2007).

Orexin activation of hippocampal ACh release

In young animals, administration of OxA in either the MS or hippocampus caused a significant increase in ACh efflux. Direct hippocampal infusion elicited an immediate increase in local ACh efflux that persisted throughout the length of OxA application and gradually returned to near basal levels following the termination of exogenous peptide exposure. Conversely, the hippocampal cholinergic response to MS infusion of OxA was delayed, but then persisted even after cessation of OxA infusion. The divergence in hippocampal cholinergic neurotransmission depending on regional application of orexin suggests pathway specific mechanisms in orexin-hippocampus interactions. We speculate that orexin infusion to the hippocampus may activate orexin receptors located on presynaptic cholinergic terminals whereas the gradual increase in hippocampal ACh efflux following MS OxA can be accounted for by the multi-synaptic pathway used through this route. Orexin receptors have been suggested to presynaptically regulate mediate glutamate release in the ventral midbrain and prefrontal cortex(Borgland et al., 2008; Lambe et al., 2005), although such a mechanism has not been reported for cholinergic terminals in these or other areas. The long duration of hippocampal ACh efflux driven by MS OxA application, meanwhile, may reflect an activation of arousal-related septo-hippocampal circuitry that persists even when exogenous peptide is removed.

Old rats did not show significant changes in hippocampal ACh efflux following either local or MS application of OxA, suggesting that the orexin receptor subtype(s) that normally mediates this response is either downregulated or, perhaps, uncoupled from its intracellular G-protein signaling cascade. Age-related declines in orexin 2 receptor (Ox2R) expression have been reported in rodent brain, including the hippocampus and a strong trend in basal forebrain (Terao et al., 2002). Whereas activation of prefrontal cortical ACh efflux by OxA appears to be primarily an orexin 1 receptor (Ox1R)-dependent phenomenon (Frederick-Duus et al., 2007), electrophysiological studies indicate that orexin excitation of septo-hippocampal cholinergic neurons is largely Ox2R-dependent (Wu et al., 2004). In situ hybridization and immunohistochemical studies further support a predominance of Ox2R in the rodent MS(Cluderay et al., 2002; Trivedi et al., 1998). Aged rodents also show diminished feeding responses to exogenous administration of OxA, which activates both orexin 1 receptors (Ox1R) and Ox2R (Kotz et al., 2005; Takano et al., 2004). Collectively, these observations suggest that the functional consequences of the diminished orexin innervation of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons are exacerbated by reduced or dysfunctional orexin receptors in the MS and hippocampus.

Functional implications of decreased orexin function in aging

An emerging body of evidence is beginning to implicate the orexins in cognitive functions beyond that which can simply be accounted for in terms of arousal. Infusion of OxB into the medial prefrontal cortex improves accuracy under conditions of high attentional demand (Lambe et al., 2005). Systemic or intrabasalis administration of an Ox1R antagonist impairs performance in a signal detection sustained attention task, further supporting a role for orexin inputs to the basal forebrain in modulating cholinergic-dependent cognition(Boschen et al., 2009; Fadel and Burk, 2010). Finally, transnasal or intravenous delivery of OxA improves performance on a delayed match-to-sample task in sleep-deprived rhesus monkeys (Deadwyler et al., 2007). Importantly, facilitation of task performance was not observed in control (non sleep-deprived) animals, suggesting that enhancement of cognitive function by orexins may be restricted to amelioration of deficits (perhaps including aging) rather than improvement of baseline performance in unimpaired animals.

With regard specifically to hippocampal-dependent cognition, intracerebroventricular infusions of OxA facilitate avoidance learning (Jaeger et al., 2002; Telegdy and Adamik, 2002) whereas CA1 infusion of the Ox1R antagonist SB-334867 impairs performance on tests of spatial learning and memory (Akbari et al., 2008; Akbari et al., 2006). Electrophysiological studies demonstrate a role for orexins in the generation of long-term potentiation (LTP) in area CA1 of hippocampal slices (Selbach et al., 2010; Selbach et al., 2004). Orexins may also play an instrumental role in the in vivo expression of LTP in the dentate gyrus (Akbari et al., 2011). Importantly, blockade of cholinergic receptors within CA1 inhibited orexin-mediated LTP, suggesting that cholinergic neurotransmission is required for orexin-mediated synaptic strengthening (Selbach et al., 2004). Collectively, these studies suggest that orexin in general, and orexin modulation of septo-hippocampal cholinergic transmission, in particular, is important for cognitive function. Thus, reduced orexin innervations of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and the failure of exogenous orexin to activate hippocampal acetylcholine release in aged animals is likely to contribute to age-related cognitive deficits.

In addition to LTP, hippocampal theta represents an additional physiological correlate of septo-hippocampal-related cognitive function. Lesion studies suggest that orexin inputs to the MS play an important role in the generation of hippocampal theta (Gerashchenko et al., 2001). Narcoleptic canines, with a loss of function mutation in Ox2R, show axonal degeneration in the MS/diagonal band region of the basal forebrain (Siegel et al., 1999). Humans with narcolepsy have dramatically reduced numbers of orexin neurons (Nishino et al., 2000; Thannickal et al., 2000) and show subtle, but significant cognitive deficits, even during periods of normal wakefulness (Naumann et al., 2006; Rieger et al., 2003). Thus, reduced orexin innervation of the septo-hippocampal pathway and/or diminished postsynaptic responsiveness to endogenously-released orexin could contribute to dysfunction in arousal, learning and memory processes related to hippocampal theta rhythms.

In conclusion, we have shown that aging is associated with reduced innervation of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons by orexins and a marked loss of the ability of exogenous orexin to activate hippocampal ACh release. Dysregulation of septo-hippocampal cholinergic transmission in aging, in the absence of frank degeneration of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, could reflect a role for the orexin system in age-related cognitive decline.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Aging grant R01 AG030646 to JF.

References

- Akbari E, Motamedi F, Davoodi FG, Noorbakhshnia M, Ghanbarian E. Orexin-1 receptor mediates long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus area of freely moving rats. Behav Brain Res. 2011;216(1):375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari E, Motamedi F, Naghdi N, Noorbakhshnia M. The effect of antagonization of orexin 1 receptors in CA1 and dentate gyrus regions on memory processing in passive avoidance task. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187(1):172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari E, Naghdi N, Motamedi F. Functional inactivation of orexin 1 receptors in CA1 region impairs acquisition, consolidation and retrieval in Morris water maze task. Behav Brain Res. 2006;173(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigoni E, Mochizuki T, Scammell TE. Activation of the basal forebrain by the orexin/hypocretin neurones. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;198(3):223–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Smith RJ, Moorman DE, Richardson KA. Role of lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward processing and addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56 Suppl 1:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi L, Ballini C, Colivicchi MA, Della Corte L, Giovannini MG, Pepeu G. Investigation on acetylcholine, aspartate, glutamate and GABA extracellular levels from ventral hippocampus during repeated exploratory activity in the rat. Neurochem Res. 2003;28(3–4):565–573. doi: 10.1023/a:1022881625378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Storm E, Bonci A. Orexin B/hypocretin 2 increases glutamatergic transmission to ventral tegmental area neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28(8):1545–1556. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschen KE, Fadel JR, Burk JA. Systemic and intrabasalis administration of the orexin-1 receptor antagonist, SB-334867, disrupts attentional performance in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;206:205–213. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1596-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broberger C, De Lecea L, Sutcliffe JG, Hokfelt T. Hypocretin/orexin- and melanin-concentrating hormone-expressing cells form distinct populations in the rodent lateral hypothalamus: relationship to the neuropeptide Y and agouti gene-related protein systems. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402(4):460–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell SE, Conti B. Age- and gender-specific changes of hypocretin immunopositive neurons in C57Bl/6 mice. Neuroscience Letters. 2010;472(1):29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluderay JE, Harrison DC, Hervieu GJ. Protein distribution of the orexin-2 receptor in the rat central nervous system. Regul Pept. 2002;104(1–3):131–144. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Zaborszky L. Organization of ascending hypothalamic projections to the rostral forebrain with special reference to the innervation of cholinergic projection neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1991;306(4):631–667. doi: 10.1002/cne.903060408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(1):322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, Sutcliffe JG, Fabre V. Hypocretins/orexins as integrators of physiological information: lessons from mutant animals. Neuropeptides. 2002;36(2–3):85–95. doi: 10.1054/npep.2002.0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler SA, Porrino L, Siegel JM, Hampson RE. Systemic and nasal delivery of orexin-A (Hypocretin-1) reduces the effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance in nonhuman primates. J Neurosci. 2007;27(52):14239–14247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3878-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MW. The effects of aging on hippocampal and cortical projections of the forebrain cholinergic system. Brain Res. 1987;434(4):423–438. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(87)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermann E, Serafin M, Bayer L, Machard D, Saint-Mleux B, Jones BE, Muhlethaler M. Orexins/hypocretins excite basal forebrain cholinergic neurones. Neuroscience. 2001;108(2):177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana RA, Reis KM, Valentino RJ, Berridge CW. Organization of hypocretin/orexin efferents to locus coeruleus and basal forebrain arousal-related structures. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481(2):160–178. doi: 10.1002/cne.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel J, Burk JA. Orexin/hypocretin modulation of the basal forebrain cholinergic system: Role in attention. Brain Res. 2010;1314:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel J, Frederick-Duus D. Orexin/hypocretin modulation of the basal forebrain cholinergic system: insights from in vivo microdialysis studies. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(2):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel J, Pasumarthi R, Reznikov LR. Stimulation of cortical acetylcholine release by orexin A. Neuroscience. 2005a;130(2):541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel J, Pasumarthi R, Reznikov LR. Stimulation of cortical acetylcholine release by orexin A. Neuroscience. 2005b;130(2):541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel J, Sarter M, Bruno JP. Basal forebrain glutamatergic modulation of cortical acetylcholine release. Synapse. 2001;39(3):201–212. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010301)39:3<201::AID-SYN1001>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick-Duus D, Guyton MF, Fadel J. Food-elicited increases in cortical acetylcholine release require orexin transmission. Neuroscience. 2007;149(3):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Nicolle MM. Animal models of normal aging: relationship between cognitive decline and markers in hippocampal circuitry. Behav Brain Res. 1993;57(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerashchenko D, Salin-Pascual R, Shiromani PJ. Effects of hypocretin-saporin injections into the medial septum on sleep and hippocampal theta. Brain Res. 2001;913(1):106–115. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02792-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Yang L, Gitzen J, Kissinger PT, Vreeke M, Heller A. Detection of basal acetylcholine in rat brain microdialysate. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1995;670(2):323–327. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(95)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger LB, Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE. Effects of orexin-A on memory processing. Peptides. 2002;23(9):1683–1688. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler BA, Stanley EM, Frederick-Duus D, Fadel J. Age-related loss of orexin/hypocretin neurons. Neuroscience in press; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotz CM, Mullett MA, Wang C. Diminished feeding responsiveness to orexin A (hypocretin 1) in aged rats is accompanied by decreased neuronal activation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289(2):R359–R366. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00717.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambe EK, Olausson P, Horst NK, Taylor JR, Aghajanian GK. Hypocretin and nicotine excite the same thalamocortical synapses in prefrontal cortex: correlation with improved attention in rat. J Neurosci. 2005;25(21):5225–5229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippa AS, Pelham RW, Beer B, Critchett DJ, Dean RL, Bartus RT. Brain cholinergic dysfunction and memory in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 1980;1(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(80)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Rogers J. Age-related shrinkage of cortically projecting cholinergic neurons: a selective effect. Ann Neurol. 1987;22(1):31–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Wainer BH, Levey AI. Central cholinergic pathways in the rat: an overview based on an alternative nomenclature (Ch1-Ch6) Neuroscience. 1983;10(4):1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore H, Stuckman S, Sarter M, Bruno JP. Stimulation of cortical acetylcholine efflux by FG 7142 measured with repeated microdialysis sampling. Synapse. 1995;21(4):324–331. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann A, Bellebaum C, Daum I. Cognitive deficits in narcolepsy. J Sleep Res. 2006;15(3):329–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S, Ripley B, Overeem S, Lammers GJ, Mignot E. Hypocretin (orexin) deficiency in human narcolepsy. Lancet. 2000;355(9197):39–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Porkka-Heiskanen T, Alanko L, Kalinchuk A, Heiskanen S, Stenberg D. The effect of age on preproorexin gene expression and contents of orexin A and B in the rat brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(2):231–238. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznikov LR, Reagan LP, Fadel JR. Activation of phenotypically distinct neuronal subpopulations in the anterior subdivision of the rat basolateral amygdala following acute and repeated stress. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508(3):458–472. doi: 10.1002/cne.21687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger M, Mayer G, Gauggel S. Attention deficits in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep. 2003;26(1):36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig ES, Barnes CA. Impact of aging on hippocampal function: plasticity, network dynamics, and cognition. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69(3):143–179. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T. Roles of orexin/hypocretin in regulation of sleep/wakefulness and energy homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9(4):231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92(4):573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai N, Ueta Y, Nakazato M, Ozawa H. Developmental and aging change of orexin-A and -B immunoreactive neurons in the male rat hypothalamus. Neuroscience Letters. 2010a;468(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai N, Ueta Y, Nakazato M, Ozawa H. Developmental and aging change of orexin-A and -B immunoreactive neurons in the male rat hypothalamus. Neurosci Lett. 2010b;468(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach O, Bohla C, Barbara A, Doreulee N, Eriksson KS, Sergeeva OA, Haas HL. Orexins/hypocretins control bistability of hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity through co-activation of multiple kinases. Acta Physiologica. 2010;198(3):277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach O, Doreulee N, Bohla C, Eriksson KS, Sergeeva OA, Poelchen W, Brown RE, Haas HL. Orexins/hypocretins cause sharp wave- and theta-related synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus via glutamatergic, gabaergic, noradrenergic, and cholinergic signaling. Neuroscience. 2004;127(2):519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman KA, Kuster JE, Dean RL, Bartus RT, Friedman E. Presynaptic cholinergic mechanisms in brain of aged rats with memory impairments. Neurobiol Aging. 1981;2(2):99–104. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(81)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM, Nienhuis R, Gulyani S, Ouyang S, Wu MF, Mignot E, Switzer RC, McMurry G, Cornford M. Neuronal degeneration in canine narcolepsy. J Neurosci. 1999;19(1):248–257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00248.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano S, Kanai S, Hosoya H, Ohta M, Uematsu H, Miyasaka K. Orexin-A does not stimulate food intake in old rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287(6):G1182–G1187. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00218.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telegdy G, Adamik A. The action of orexin A on passive avoidance learning. Involvement of transmitters. Regul Pept. 2002;104(1–3):105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terao A, Apte-Deshpande A, Morairty S, Freund YR, Kilduff TS. Age-related decline in hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 messenger RNA levels in the mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332(3):190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000;27(3):469–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi P, Yu H, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LH, Guan XM. Distribution of orexin receptor mRNA in the rat brain. FEBS Lett. 1998;438(1–2):71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CF, Bertorelli R, Sacconi M, Pepeu G, Consolo S. Decrease of brain acetylcholine release in aging freely-moving rats detected by microdialysis. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9(4):357–361. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(88)80081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Zaborszky L, Hajszan T, van den Pol AN, Alreja M. Hypocretin/orexin innervation and excitation of identified septohippocampal cholinergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24(14):3527–3536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5364-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaborszky L, Cullinan WE. Hypothalamic axons terminate on forebrain cholinergic neurons: an ultrastructural double-labeling study using PHA-L tracing and ChAT immunocytochemistry. Brain Res. 1989;479(1):177–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J-H, Sampogna S, Morales FR, Chase MH. Age-related changes of hypocretin in basal forebrain of guinea pig. Peptides. 2005;26(12):2590–2596. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]