Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pancreatic cancer (PanC) presents at late stage with high mortality. Effective early detection methods are needed. Aberrantly methylated genes are unexplored as markers for noninvasive detection by stool testing. We aimed to select discriminant methylated genes and to assess accuracy of these and mutant KRAS in stool to detect PanC.

METHODS

Nine target genes were assayed by real-time methylation-specific PCR (MSP) in bisulfite-treated DNA from microdissected frozen specimens of 24 PanC cases and 30 normal colon controls. Archived stools from 58 PanC cases and 65 controls matched on sex, age, and smoking were analyzed. Target genes from fecal supernatants were enriched by hybrid capture, bisulfite-treated, and assayed by MSP. KRAS mutations were assayed using the QuARTS technique.

RESULTS

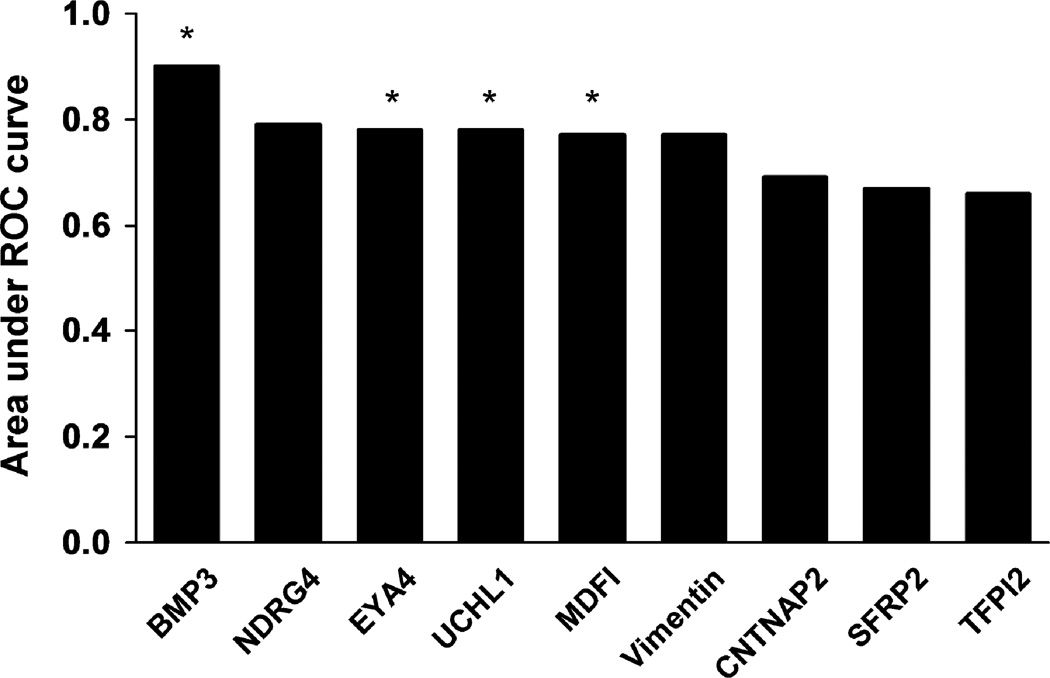

Areas under the receiver operating characteristics curves (AUCs) for tissue BMP3, NDRG4, EYA4, UCHL1, MDFI, Vimentin, CNTNAP2, SFRP2 and TFPI2 were 0.90, 0.79, 0.78, 0.78, 0.77, 0.77, 0.69, 0.67, and 0.66, respectively. The top 4 markers and mutant KRAS were evaluated in stool. BMP3 was the most discriminant methylation marker in stool. At 90% specificity: methylated BMP3 alone detected 51% of PanCs, mutant KRAS detected 50%, and combination detected 67%. AUCs for methylated BMP3, mutant KRAS, and combination in stool were 0.73, 0.75, and 0.85, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that stool assay of a methylated gene marker can detect PanC. Among candidate methylated markers discriminant in tissue, BMP3 alone performed well in stool. Combining methylated BMP3 and mutant KRAS increased stool detection over either marker alone.

Keywords: Early detection, pancreatic cancer, biological markers, epigenetics, feces/analysis, bone morphogenetic protein 3, mutant KRAS

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PanC) remains the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the US.1 Patients typically present with symptomatic, advanced stage disease.2 Among the minority patients going to surgery, 5 year survival is less than 25%; however, survivors have early stage disease at resection.3, 4 Sadly, survival rates have changed little over recent decades.

To curb the high mortality rates from PanC, effective and affordable methods for early detection are urgently needed. To date, screening efforts have been restricted to high risk subsets using invasive and expensive imaging or endoscopic procedures.5 Such focused efforts have little effect on overall PanC outcomes, as the large majority arise in those without known pre-disposition.6 Furthermore, this intensive procedural approach to PanC screening would be cost-prohibitive and potentially harmful at the population level. 7–11

Noninvasive detection of pancreatic neoplasia is biologically rational and supported by observations to date. Pancreatic cancers and precursors exfoliate into the local effluent and ultimately stool. Mutant KRAS can be sequenced from pancreatic juice from patients with PanC.12, 13 Our group14 and others15, 16 have demonstrated that mutant KRAS in stool can reflect the presence of both pancreatic cancer and precancer. However, no single mutation marker has optimal coverage of PanC, and panels of mutation markers can be analytically unwieldy for use in routine practice.

Aberrant DNA methylation represents a more broadly informative class of candidate tumor markers. For example, a combination of just 2 methylated gene markers may perfectly discriminate colorectal cancer and precancer from normal mucosa in tissue,17 and such informative methylation markers incorporated into a next-generation stool DNA test18 outperforms earlier tests based on assays of multiple point mutations.19, 20 To our knowledge, use of methylated markers in stool to detect PanC has not been reported.

Several promising methylated gene markers have been identified for PanC and precursors in tissue, including MDFI (MyoD family inhibitor) and CNTNAP2 (contactin associated protein-like 2),21 SFRP2 (secreted frizzled related protein 2)22 alone or in combination with UCHL1 (ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterase L1),23 and methylated tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (TFPI2).24 These markers may also be aberrantly methylated in other cancers. For example in colorectal tissue,17 TFPI2 appears to be particularly discriminating along with BMP3 (bone morphogenic protein 3), NDRG4 (N-myc down-regulated gene) and vimentin.

We hypothesized that stool detection of PanC should be feasible using aberrantly methylated DNA markers. Candidate markers would include those previously shown to discriminate pancreatic and colorectal neoplasms from normal tissue. Our study aims were to: 1) select candidate methylation markers for PanC in tissue; 2) determine which markers discriminate between PanC cases and normal controls using matched archival stools; and 3) assess the impact of clinical covariates on test performance.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This investigation began at the tissue level with selection of candidate methylation markers that discriminate PanC from normal colon epithelium using a case-control study design on archival specimens (Tissue Study). Since our intent was to select candidate markers for stool testing and since exfoliation from normal colorectum would proportionately far exceed that of normal pancreas, normal colon (rather than normal pancreas) controls were purposely selected to exclude markers likely to cause elevated background levels in stool. We evaluated markers reported by others to be discriminant for pancreatic neoplasms (MDFI, CNTNAP2, SFRP2, UCHL1, TFPI2, Vimentin) along with several markers that our group has found to be useful for stool detection of colorectal neoplasia (BMP3, NDRG4, EYA4) but which have not yet been studied in PanC. The most sensitive and specific tissue markers were selected for subsequent assessment in stool (Stool Study). Using archival stools from well-characterized patients, candidate markers were assayed in blinded fashion from 58 case patients with biopsy-proven pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and from 65 demographically matched control patients with normal colonoscopy and no known PanC, chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic exocrine deficiency or prior pancreatic surgery. Mutant KRAS was also assayed in all stools to assess complementary value. This study was approved by the Mayo Institutional Review Board.

Setting and Participants

Tissue Study

Patients had undergone distal pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy or colectomy at Mayo Clinic (Rochester MN) with an archived surgical specimen and a confirmed pathologic diagnosis. De-identified PanC cases were compared to unmatched non-neoplastic colonic epithelial controls for which DNA had been extracted and stored by the Mayo Clinic Biospecimens Accessioning Processing lab. All participants signed a research authorization prior to use of tissue specimens.

Stool Study

PanC cases seen in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology or Medical Oncology were sequentially recruited for a biospecimen archive (Mayo Clinic Pancreas SPORE Registry). Only those who submitted a stool specimen, had a biopsy-proven diagnosis of PanC, and had complete clinical staging were included. Control specimens were drawn from a stool archive submitted by volunteers enrolled in a colorectal cancer screening study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for use of their stool sample. Cases and controls were frequency matched on variables that could potentially influence DNA methylation levels, including sex, smoking status (current/former vs never) and age (in years). Cases were stratified by American Joint Committee on Cancer stage (I – IV) and by site within the pancreas (ampulla/head vs body/tail) to assess for impact of these variables on marker levels in the stool.

Clinical data were abstracted from the electronic medical record by an experienced study coordinator using a protocolized collection form. Patients were excluded for known neoplastic disease at a different aerodigestive site; prior cancer treatment with surgery, chemotherapy or radiation; or for stools collected within 1 week of oral contrast or bowel catharsis for diagnostic procedures.

Stool Collection and Processing

Whole stools were collected using a plastic bucket device mounted on the toilet seat. Following defecation, patients immediately poured a stabilizing buffer solution25 onto the stool and sealed the bucket with a water-tight lid. Samples were collected either from patients’ home and express mailed or from the outpatient setting and delivered to the processing lab via intra-institutional courier systems. Upon receipt into our central processing laboratory, stools were promptly homogenized, aliquoted, and frozen at −80C until assay.

Assay Technique

DNA Extraction in Tissue Study

DNA was previously extracted from frozen tissues using a phenol-chloroform protocol and suspended in buffer. Quantification of total DNA was performed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE)

Real-Time Methylation-Specific PCR (MSP) in Tissue Study

DNA was bisulfite treated using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) and eluted in buffer. One µl bisulfite-treated DNA was used as a template for methylation quantification with a fluorescence-based real-time PCR. Primers for each marker were designed to target the bisulfite-modified methylated sequences of each gene (IDT, Coralville IA). A region without cytosine-phosphate-guanine sites in the β-actin gene was also quantified with real-time PCR using primers recognizing the bisulfite-converted sequence as a reference of bisulfite treatment and DNA input. PCR reactions for tissue DNA samples were performed with SYBR Green master mix (Roche, Germany).

All reactions were run on Roche 480 LightCyclers (Indianapolis, IN). Bisulfite-treated CpGenome Universal Methylated DNA (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used as a positive control, and serially diluted to create standard curves for all plates.

Sequence-Specific Gene Capture in Stool Study

Stool samples were weighed and diluted with additional buffer to 3 gram equivalents. Stools were centrifuged and the supernatant incubated with polyvinylpyrrolidone (Crosby & Baker, Westport MA) to remove solids and PCR inhibitors. Sodium chloride and guanidine thiocyanate (Sigma, St. Louis MO) denaturation buffer were added to clarified stool supernatant and denatured in a water bath at 90C for 10 minutes. 150 µL of carboxylic acid coated capture beads with amino conjugated oligonucleotides complimentary to target sequences (IDT, Coralville IA) were added and mixed to allow hybridization at room temperature. Sample tubes were then placed on magnetic beads and supernatant removed before a 3-step wash in MOPS buffer (10 mM MOPS, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) to remove remaining inhibitors. Heated tRNA elution buffer was then added and the beads removed with centrifugation. Two multiplex capture reactions of 4 MSP targets and 4 KRAS targets were performed separately.

Marker Assays in Stool Study

Methylation Markers

After capture, target DNA was bisulfite treated and amplified using MSP reactions as in the tissue study but with a 5 µL DNA sample.

KRAS Markers

KRAS gene was first PCR amplified with primers flanking codons 12/13 using 10 µl of captured KRAS DNA as template. PCR was conducted with LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche, Germany) and 200 nM of each primer at 95C for 3 minutes, and 15 cycles at 95C for 20 seconds, 62C for 30 seconds, and 72C for 30 seconds. Each amplified sample was diluted 500-fold in nuclease free water; 10 µl of the 500-fold sample dilutions was added to 96-well PCR plate. QuARTS (Quantitative Allele-specific Real-time Target and Signal amplification) assays were then used to evaluate four mutations at codons 12/13 of the KRAS gene (G12C, G12V, G12D, G13D). Each mutation assay was run separately. Each QuARTS reaction incorporated 400–600 nM primers and detection probes, 100 nM invasive oligonucleotide, 600–700 nM each of FAM (Hologic, Madison WI), fluorescence resonance energy transfers (FRETs), 6.675 ng/µl Cleavase 2.0 (Hologic), 1 unit GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison WI), 10 mM MOPS, 7.5 mM MgCl2, and 250 µM each dNTP. QuARTS cycling conditions consisted of 95C for 3 minutes, 10 cycles at 95C for 20 seconds, 67C for 30 seconds, and 70C for 30 seconds, 45 cycles at 95C for 20 seconds, 53C for 1 minute, and 70C for 30 seconds, and 40C hold for 30 seconds. Standard curves were made of 10-fold serially diluted engineered plasmids with corresponding gene inserts. Bisulfite-treated CpGenomeTM universal methylated DNA (Millipore) and human genomic DNA (Novogen, Ontario Canada) were used as positive and negative controls. Each plate contained standards made of engineered plasmids, positive and negative controls, and water blanks, and was run in a LightCycler 480 (Roche). The concentration of each mutation marker in 50 µl of KRAS was calculated based on the 500-fold dilution factor and an amplification efficiency of 1.95. All oligonucleotide sequences for the tissue and the stool studies are available on request.

Quality Assurance Measures

All assays were conducted by two investigators (J.B.K., W.R.T.) in accordance with standard operating procedures drafted for these techniques in our laboratory. All reactions were run on the same two thermocycler devices; all DNA samples were processed using the same reagents. Probes and primers were tested prior to assay use to determine optimal duration of heating and cooling cycles. The stool study assays were conducted blind to the clinical diagnosis, after samples were retrieved by a third technician (T.C.Y.). Samples for which β-actin did not amplify during MSP were excluded. The blinding code was broken at the time of analysis.

Statistical Considerations

Tissue Study

The methylation level for each candidate gene was defined as the absolute copy number of methylated target sequences after PCR amplification, expressed as a continuous variable. The primary approach to combining the individual DNA markers into a panel was stepwise logistic regression with a probability to enter the model of 0.1 and a probability to leave of 0.05. With twenty-four cases and thirty control samples available for study, the model was limited to 3 predictive DNA markers. Of all possible three variable models (a total of 56 potential models) the model with the lowest cross validation error rate was considered as the optimal model and was used to estimate the area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. ROC curves were also calculated for each individual marker. In colorectal cancer, the ability of any single marker for detection of significant lesions ranges from 20% to 40%. For the purposes of power calculation for sensitivity estimates from a logistic regression model, an optimist level of 30% was used as the null hypothesis value for the detection rate; an individual marker or panel of markers was considered discriminant if the lower boundary of the 95% confidence interval for the sensitivity estimate did not fall below 30% in a two-sided comparison. Twenty-five patients in each stratum provided 80% to distinguish a true sensitivity of 70% from 30% with a 2-sided two sample proportion test at the 5% level.

Stool Study

In a similar approach to the Tissue Study, stepwise logistic regression was used to model a marker panel. Mutant KRAS status was determined from the absolute copy number of amplified copies of the four mutations of interest. The primary endpoint was the overall sensitivity estimate of a marker panel to detect PanC at a specificity of at least 90%. From the ROC table, the numbers of true and false positives were used to calculate 95% confidence intervals for the sensitivity estimates using the efficient score method.26 To demonstrate the feasibility of the assay for detecting markers in stool from patients with PanC, we sought to show that the lower boundary of 95% confidence level of the sensitivity estimate was not less than 40%. Sixty patients in each stratum provided 80% power to distinguish a true sensitivity of 70% from 40% with a 2-sided two sample proportion test at the 5% level.

Baseline clinical characteristics were assessed using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum comparison for continuous variables. Quantitative differences of marker levels among cases and controls were also assessed by a Wilcoxon rank sum comparison. Marker levels were compared by stage (I–IV), tumor site, sex, age and smoking using linear regression. As a measure of referral bias, linear regression was also used to compare marker levels with the distance from our referral center. Sex, age and smoking were included in the stepwise regression model to assess effect modification; sixty patients in each stratum limited the number of variables in the final model to 6. Analyses were performed using JMP software (version 8.0, SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

Tissue Study

Table 1 summarizes the results of the MSP assays for each of the 9 methylation markers. Nominal logistic regression calculated an area under the ROC curve (AUC) for each individual marker (Figure 1). Methylated BMP3 proved to be most discriminant with an AUC of 0.90. A stepwise logistic regression model demonstrated complementarity with EYA4, MDFI and UCHL1; however, their combined AUC of 0.85 was less than that of BMP3 alone. These markers and BMP3 were selected for evaluation in the Stool Study.

Table 1.

Methylation Specific Polymerase Chain Reaction Results: Tissue Study

| Marker | Median copy number (Inter-quartile range) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 23) | Controls (n = 30) | ||

| BMP3 | 117 (13 – 517) | 3.7 (3.7 – 8.4) | <0.0001 |

| NDGR4 | 56 (3 – 815) | 0.14 (0.04 – 2.7) | 0.0003 |

| EYA4 | 165 (12 – 722) | 10.1 (3.4 – 31) | 0.0004 |

| UCHL1 | 892 (7.4 – 1419) | 8.6 (3.3 – 12.6) | 0.0005 |

| MDFI | 131 (10.2 – 683) | 5.2 (1.9 – 16.3) | 0.0008 |

| Vimentin | 5.8 (1.9 – 300) | 1.2 (0.02 – 3.7) | 0.0007 |

| CNTNAP2 | 110 (18 – 1070) | 22.4 (10 – 74) | 0.02 |

| SFRP2 | 318 (10.4 – 757.5) | 37.2 (12.2 – 106) | 0.04 |

| TFPI2 | 309 (15.2 – 453) | 36 (6.8 – 70) | 0.04 |

β-actin did not amplify in 1 case sample

Figure 1.

Areas under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves for methylation marker candidates assayed from case and control tissue samples

Stool Study

From August 2006 to August 2009, 537 consecutive PanC patients were approached and 466 consented for participation in a clinical registry. Of those, 87 (19%) consented to submit a stool specimen. Three patients did not have biopsy confirmation of PanC diagnosis and 26 provided stool samples that did not meet the pre-established minimum weight threshold of 3 g. The remaining 58 PanC patients were included. Sixty-five matched control samples were selected from 255 eligible patients prospectively enrolled in a bio-bank registry between July 2006 and September 2010. For all eligible samples, the median time from defecation to laboratory receipt and processing of stools was 1 day (range, 0 – 3).

As per design, there were no significant differences in sex, smoking history or age between cases and controls (Table 2). The median distance patients traveled was determined by zip code of primary residence. Cases traveled a median of 248 miles, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 111 – 522 miles, from their primary residence to our center; this was significantly farther than for control patients, who traveled a median of 13.5 (IQR, 2.5 – 49) miles (p< 0.0001).

Table 2.

Patient and Lesion Characteristics in the Stool Study

| Cases | Controls | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | 57 | 62 | |

| Men (%) | 41 (72) | 41 (66) | 0.49 |

| Smokers (%) | 39 (68) | 43 (69) | 0.91 |

| Median Age (IQR) | 64 (59–73) | 62 (55–70) | 0.08 |

| Median Distance traveled (IQR), miles |

248 (111–522) |

13.5 (2.5–49) |

< 0.0001 |

|

Lesion Location (%) |

|||

| Head | 38 (66) | - | - |

| Body/tail | 19 (33) | - | - |

| Stage (%) | |||

| I | 3 (5) | - | - |

| II | 20 (35) | - | - |

| III | 15 (26) | - | - |

| IV | 19 (33) | - | - |

Wild-type KRAS did not amplify in 3 cases and 1 control

β-actin did not amplify in 1 case and 3 controls

IQR = interquartile range

Among cases, 38 (66%) of tumors were located in the pancreatic head. Stage I tumors were under-represented, consistent with the natural history of the disease at presentation. Stage distribution of PanC was as follows: stage I (5%), II (35%), III (26%), and IV (33%).

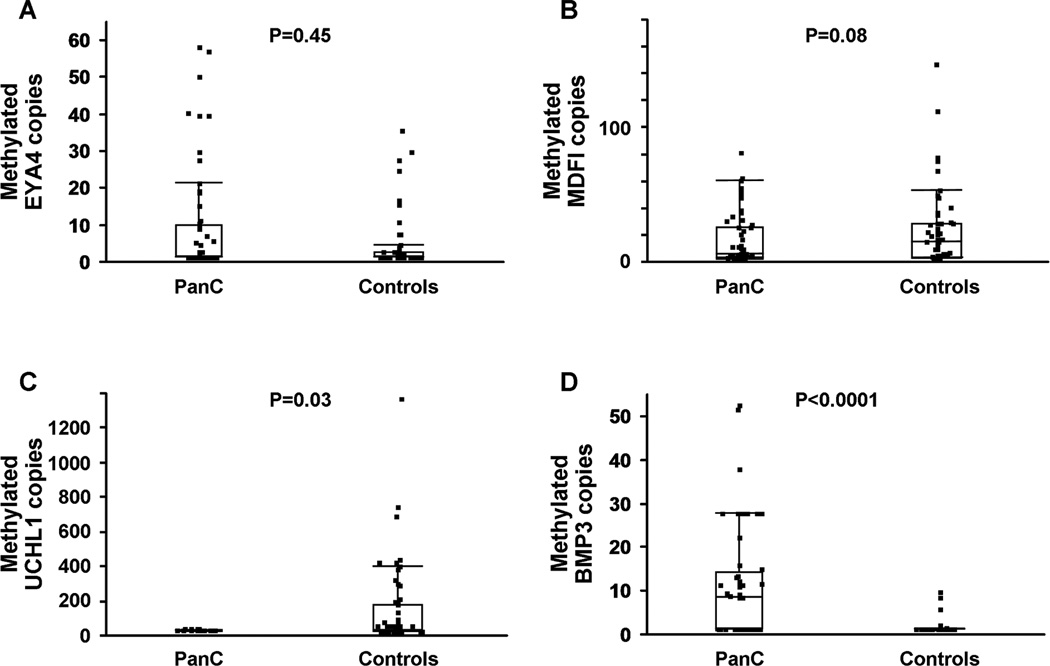

Methylated BMP3 was found at significantly higher levels in stools from PanC cases than from control samples. Median copy number among cases was 7.5 (IQR, 0 – 13.5 copies compared to 0 (IQR, 0-0) copies among controls (p <0.0001). The distributions of methylated EYA4 and MDFI were not significantly different between cases and controls (Figure 2). Paradoxically, UCHL1 levels were significantly higher in control samples than in cases, with median copies of 4.25 (IQR, 0–7.2) and 7.2 (IQR, 0–149) respectively (p = 0.03).

Figure 2.

Distribution of methylated copy numbers of (A) EYA4, (B) MDFI, (C)UCHL1 and (D) BMP3 assayed from case and control stool samples. Box plots depict interquartile range and whiskers extend to 1.5x the interquartile range; PanC = pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

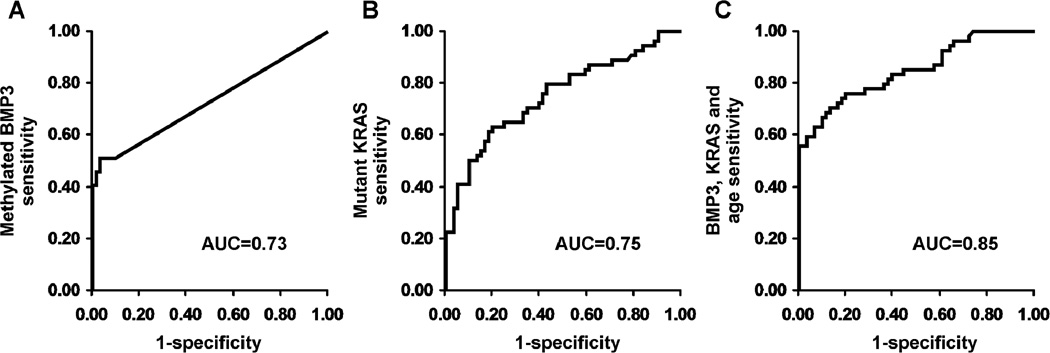

By univariate logistic regression, methylated BMP3 had an AUC of 0.73. Setting specificity to 90%, the sensitivity was 51% (95% confidence interval, 37 – 64%). A multivariate regression model of the 4 KRAS mutations had an AUC of 0.75. Setting specificity to 90%, the sensitivity was 50% (36 – 64%). Stepwise logistic regression assessed the combination of BMP3 and KRAS as well as potential interactions with each of the matching variables. Smoking history, sex and two of the KRAS mutations (G12V, G12D) were non-contributory. The final model included methylated BMP3, two KRAS mutations (G12C, G13D), age and the interaction of age with methylated BMP3; the resulting AUC was 0.85. At 90% specificity, the sensitivity was 67% (52 – 79%) (Figure 3). Inclusion of methylated UCHL1 improved the AUC to 0.88. However, due to the discordant results between the tissue study and the stool study, methylated UCHL1 was excluded from the final model.

Figure 3.

Stool Study Receiver Operating Characteristics Curves. (A) Univariate model of methylated BMP3 to predict case and control status. (B) Multivariate model of 4 KRAS mutations to predict case and control status. (C) Multivariate model for prediction of case and control status using methylated BMP3, KRAS G12C mutation, KRAS G13D mutation, age and the interaction of age with methylated BMP3: Ln (odds PanC) = −2.67 + 0.28 (methylated BMP3 copies) + 0.012 (KRAS G12C copies) −0.01 (KRAS G13D copies)+ 0.02 (Age, years) + −0.01 (Age × methylated BMP3 copies); AUC = Area under the curve.

Covariates were evaluated. There was no association between tumor site and the copy numbers of methylated BMP3 (p = 0.1), KRAS G12C (p = 0.9) or KRAS G13D (p = 0.9). There was no association between tumor stage and copy numbers of methylated BMP3 (p = 0.2), KRAS G12C (p = 0.65) or KRAS G13D (p = 0.85). Univariate associations of age, sex and smoking with BMP3, KRAS G12C and KRAS G13D were all non-significant. There was no association of the distance from our center and the copy numbers of methylated BMP3 (p = 0.2), KRAS G12C (p = 0.18) or KRAS G13D (p = 0.08).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that stool assay of a methylated gene marker can be used to detect pancreatic cancer. Combined stool assay of methylated BMP3 and mutant KRAS increased PanC detection over either marker alone. Age may modify the discriminant value of the stool assays for both markers; however, neither sex nor smoking history appeared to influence the results. Importantly, neither methylated BMP3 levels nor copies of mutant KRAS showed significant trends across tumor stage or site. The lack of association between tumor stage and mutant KRAS was corroborated in preliminary results from a companion study using an independent sample set from an outside institution.27

For a marker to effectively detect PanC by stool assay, it must both be broadly expressed in PanC tissue and be absent or at very low levels in normal gastrointestinal epithelia. Given the large surface area of the colon from which DNA can exfoliate, our findings highlight the importance of accounting for the background levels of each marker in the biospecimen milieu. Despite the use of analytically sensitive assays, many methylated genes that were discriminant in tissue could not be detected above background levels in stool. It is possible that some of the markers not studied in stools may also have been discriminant, specifically NDRG4 which also showed extremely high specificity in the tissue study. In contrast to the tissue findings, UCHL1 appeared to have negative predictive value in stools; however, we opted not to include this marker in the logistic model until a biological mechanism for this finding can be elucidated and stool findings can be corroborated.

While KRAS mutations are frequently found in PanC, less is known about methylated BMP3. Bone morphogenetic proteins and other members of the transforming growth factor β superfamily are implicated pancreatic tumor biology.28 BMP2 and its receptors were found to be overexpressed in pancreatic cancer tissues and correlated with prognosis.29 Hamada and colleagues showed that BMP4 induces the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a pancreatic cancer cell line through induction of transcription factor MSX2.30 In colon cancer, BMP3 has a tumor suppressor role when phenotypically methylated in association with the BRAF V600E mutation.31 In colon cancer cell lines with methylation-dependent BMP3 down-regulation, cell colony growth suppression was reliably observed after re-introduction of BMP3 coding sequences.32 Methylation of the BMP3 promotor has also been described in sub-types of stomach,33 lung34 and breast cancers.35

KRAS is thought to be mutated early in the development of PanC based on prevalent KRAS mutations in non-invasive pre-cursors.36 In contrast, some studies suggest that certain methylation markers may be more specific for cancer and high-grade precursors.21, 22, 37, 38 In the present study, the combination of markers in a logistic regression model detected 67% of the cancers at 90% specificity.

Plasma assay of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) is currently the most widely used noninvasive test for detection of PanC. In a study from our institution, plasma CA 19-9 detected PanC with a sensitivity of 75% at 94% specificity.39 Because we did not aim to make a direct comparison between mBMP3 and CA 19-9 in the present study, CA 19-9 levels were not available on control patients. However, an informal assessment suggests that mBMP3 is complementary to CA 19-9. Of the 48 PanC patients in our study sample who had both stool BMP3 assay and CA 19-9 measurements, CA 19-9 was positive in 35 patients (73%), using a cut-off value of 70 IU/mL (94% specificity on historical controls).39 Though stool mBMP3 was positive in 27 patients (56%) at 90% specificity, the combination of markers detected 45/48 PanC tumors (94%). Of 13 PanC patients who were CA 19-9 negative, stool mBMP3 detected an additional 10 cases, 5 of whom had potentially resectable tumors. Given this intriguing preliminary observation, further comparisons would be of interest when stool DNA testing is optimized for this application.

Our study has several strengths. First, the laboratory personnel who performed the stool analyses were blinded to the clinical diagnosis of the patients. Second, the stool study patients were tightly matched on potential confounding variables. Though case patients were more likely than controls to be referred, their enrollment was sequential and there was no association between marker levels and the distance of the patients’ primary residence, a surrogate marker of potential referral bias. Third, the low prevalence of PanC in the general population minimized the risk of misclassification bias among the controls. Similarly, prevalence/incidence bias, while possible, was also unlikely given the near uniform lethality of the disease.

Study limitations should also be noted. Only 19% of the eligible pancreas cancer patients during the enrollment time consented to participate in the stool collection protocol, introducing the potential for non-responder/volunteer bias. Enrollment rates in large trials of stool DNA for colorectal neoplasia detection have not been published for direct comparison.19, 20 This will be an important area of scrutiny in subsequent studies validating these results on a larger scale. Sensitivity and specificity estimates obtained in the case-control setting are also subject to spectrum bias; and the ultimate performance characteristics of the test must incorporate population prevalence of the disease. Future studies of methylation marker panels for pancreatic cancer detection will also need to include diseased controls, such as patients with chronic pancreatitis, early in the development process.40

Patients with precursor lesions of PanC were not included in the present study. Our preliminary data suggest that intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms can be detected with high sensitivity by stool assay of mutant KRAS.27 Stool assay of methylation markers remains to be evaluated for detection of PanC precursor lesions.

Encouraged by these results, we are conducting an un-biased, genome-wide search to find new methylation marker candidates. Ideally, candidate markers should have tumor site specificity permitting the use of stool DNA markers unique for PanC and precursors. Such site-specific markers might in the future be used in a stand-alone test or as part of a panel of markers for screening multiple aerodigestive neoplasms by stool testing.41 We are enrolling patients to validate these and other markers in both high-risk surveillance42 and population screening settings.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support:

This work was supported by the Charles Oswald Foundation, the Clinical Core of the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (P30DK084567), the Mayo Clinic SPORE in Pancreatic Cancer (P50 CA102701) and the Lustgarten Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Mayo Clinic is a minor equity investor in and has licensed intellectual property to Exact Sciences. Dr. Ahlquist, Mr. Taylor, and Ms. Yab hold patents related to stool DNA testing and, consistent with Mayo Clinic policy, could share in potential future royalties. Dr. Kisiel, Mr. Taylor, Ms. Yab and Dr. Ahlquist have filed a provisional patent application based on the results presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Biology and management of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2007;56(8):1134–1152. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.103333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleary SP, Gryfe R, Guindi M, et al. Prognostic factors in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: analysis of actual 5-year survivors. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(5):722–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;221(6):721–731. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00011. discussion 31-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canto MI, Goggins M, Hruban RH, et al. Screening for early pancreatic neoplasia in high-risk individuals: a prospective controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(6):766–781. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.02.005. quiz 665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schenk M, Schwartz AG, O'Neal E, et al. Familial risk of pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(8):640–644. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.8.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein AP, Hruban RH, Brune KA, Petersen GM, Goggins M. Familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer J. 2001;7(4):266–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gudlaugsdottir S, van Blankenstein M, Dees J, Wilson JH. A majority of patients with Barrett's oesophagus are unlikely to benefit from endoscopic cancer surveillance. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13(6):639–645. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inadomi JM. Surveillance in Barrett's esophagus: a failed premise. Keio J Med. 2009;58(1):12–18. doi: 10.2302/kjm.58.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh JM, Ho W, Hur C. Cost-effectiveness of endoscopic surveillance of gastric ulcers to improve survival. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rulyak SJ, Kimmey MB, Veenstra DL, Brentnall TA. Cost-effectiveness of pancreatic cancer screening in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(1):23–29. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berthelemy P, Bouisson M, Escourrou J, Vaysse N, Rumeau JL, Pradayrol L. Identification of K-ras mutations in pancreatic juice in the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(3):188–191. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-3-199508010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo H, Sugano K, Fukayama N, et al. Detection of K-ras gene mutations at codon 12 in the pancreatic juice of patients with intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Cancer. 1997;79(5):900–905. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970301)79:5<900::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou H, Harrington JJ, Taylor WR, et al. T2036 Pan-Detection of Gastrointestinal Neoplasms By Stool DNA Testing: Establishment of Feasibility. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(Supplement 1)(5):A-625. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldas C, Hahn SA, Hruban RH, Redston MS, Yeo CJ, Kern SE. Detection of K-ras mutations in the stool of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and pancreatic ductal hyperplasia. Cancer Res. 1994;54(13):3568–3573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berndt C, Haubold K, Wenger F, et al. K-ras mutations in stools and tissue samples from patients with malignant and nonmalignant pancreatic diseases. Clin Chem. 1998;44(10):2103–2107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou HCX, Domenico M, Harrington J, Taylor W, Yab T, Ahlquist D, Lidgard G. Sensitive quantitation of methylated markers with a novel methylation-specific technology; Annual Meeting for the American Association of Clinical Chemistry; Los Angeles, CA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahlquist D, Zou H, Domanico M, Mahoney DW, Thibodeau SN, Lidgard G. Next Generation Stool DNA Testing for Detection of Colorectal Neoplasia- Early Marker Evaluation [abstract]. Presented at Colorectal Cancer: Biology to Therapy hosted by the American Association for Cancer Research; 2010 October 27–30; Philedelpia PA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, Turnbull BA, Ross ME. Fecal DNA versus fecal occult blood for colorectal-cancer screening in an average-risk population. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2704–2714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahlquist DA, Sargent DJ, Loprinzi CL, et al. Stool DNA and occult blood testing for screen detection of colorectal neoplasia. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(7):441–450. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-7-200810070-00004. W81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omura N, Li CP, Li A, et al. Genome-wide profiling of methylated promoters in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(7):1146–1156. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato N, Fukushima N, Hruban RH, Goggins M. CpG island methylation profile of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(3):238–244. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong SM, Kelly D, Griffith M, et al. Multiple genes are hypermethylated in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(12):1499–1507. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsubayashi H, Canto M, Sato N, et al. DNA methylation alterations in the pancreatic juice of patients with suspected pancreatic disease. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):1208–1217. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou H, Harrington JJ, Klatt KK, Ahlquist DA. A sensitive method to quantify human long DNA in stool: relevance to colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1115–1119. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):857–872. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang C, Kumar S, Yab TC, et al. Noninvasive Detection of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms (IPMN) and Early Stage Cancer of the Pancreas With Stool DNA Testing. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(Supplement 1)(5):S-678. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kayed H, Kleeff J, Keleg S, et al. Correlation of glypican-1 expression with TGF-beta, BMP, and activin receptors in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2006;29(5):1139–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleeff J, Maruyama H, Ishiwata T, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 exerts diverse effects on cell growth in vitro and is expressed in human pancreatic cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(5):1202–1216. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamada S, Satoh K, Hirota M, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition through MSX2 induction on pancreatic cancer cell line. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213(3):768–774. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinoue T, Weisenberger DJ, Pan F, et al. Analysis of the association between CIMP and BRAF in colorectal cancer by DNA methylation profiling. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(12):e8357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loh K, Chia JA, Greco S, et al. Bone morphogenic protein 3 inactivation is an early and frequent event in colorectal cancer development. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(6):449–460. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen XR, Wang JW, Li X, Zhang H, Ye ZY. Role of BMP3 in progression of gastric carcinoma in Chinese people. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(11):1409–1413. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai Z, Popkie AP, Zhu WG, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 3B silencing in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23(20):3521–3529. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronneberg JA, Fleischer T, Solvang HK, et al. Methylation profiling with a panel of cancer related genes: Association with estrogen receptor, TP53 mutation status and expression subtypes in sporadic breast cancer. Mol Oncol. 2011;5(1):61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moskaluk CA, Hruban RH, Kern SE. p16 and K-ras gene mutations in the intraductal precursors of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57(11):2140–2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukushima N, Sato N, Ueki T, et al. Aberrant methylation of preproenkephalin and p16 genes in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(5):1573–1581. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jansen M, Fukushima N, Rosty C, et al. Aberrant methylation of the 5' CpG island of TSLC1 is common in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and is first manifest in high-grade PanlNs. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1(3):293–296. doi: 10.4161/cbt.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chari ST, Klee GG, Miller LJ, Raimondo M, DiMagno EP. Islet amyloid polypeptide is not a satisfactory marker for detecting pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(3):640–645. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen R, Crispin DA, Pan S, et al. Pilot study of blood biomarker candidates for detection of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2010;39(7):981–988. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181dac920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahlquist DA. Next-generation stool DNA testing: expanding the scope. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(7):2068–2073. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brune K, Hong SM, Li A, et al. Genetic and epigenetic alterations of familial pancreatic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(12):3536–3542. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]