Abstract

The C-terminus domain of G protein-coupled receptors confers a functional cytoplasmic interface involved in protein association. By screening a rat brain cDNA library using the yeast two-hybrid system with the C-terminus domain of the dopamine D3 receptor (D3R) as bait, we characterized a new interaction with the PDZ domain-containing protein, GIPC (GAIP interacting protein, C terminus). This interaction was specific for the dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) and D3R, but not for the dopamine D4 receptor (D4R) subtype. Pull-down and affinity chromatography assays confirmed this interaction with recombinant and endogenous proteins. Both GIPC mRNA and protein are widely expressed in rat brain and together with the D3R in neurons of the islands of Calleja at plasma membranes and in vesicles. GIPC reduced D3R signaling, cointernalized with D2R and D3R, and sequestered receptors in sorting vesicles to prevent their lysosomal degradation. Through its dimerization, GIPC acts as a selective scaffold protein to assist receptor functions. Our results suggest a novel function for GIPC in the maintenance, trafficking, and signaling of GPCRs.

INTRODUCTION

A common regulatory mechanism of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) activity is their sequestration from the cell surface. Thus, whereas prolonged exposure to agonist leads receptors to internalization and degradation within lysosomes (Bohm et al., 1997), brief stimulation involves internalization and trafficking to sorting compartments to recycle the receptors to the cell surface (Ferguson, 2001; Claing et al., 2002). Desensitization initiates a cascade of events leading to signaling regulation starting from the uncoupling of the G protein in response to receptor phosphorylation by either second messenger-dependent protein kinases, like protein kinase A (Mason et al., 2002) or G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRK). In turn, receptor phosphorylation promotes arrestin binding, which targets many GPCR in intracellular clathrin-coated vesicles (Zhang et al., 1997a, 1997b). Emerging alternative mechanisms have been proposed, involving β-arrestin-independent, clathrin-independent and dynamin-dependent internalization routes (Kohno et al., 2002), suggesting that the complexity and specificity of GPCR-regulatory processes may reside in the combination of accessory protein functions to be unraveled yet.

Dopamine receptors are GPCRs mediating the pleiotropic actions of dopamine in the brain and peripheral tissues. Among them, D2-like receptors (D2R, D3R, and D4R), which are the major target for antipsychotic and anti-Parkinson's disease drugs (Missale et al., 1998), differ in their brain distribution and pharmacological profiles. For instance, D3R possesses a higher affinity for endogenous dopamine than D2R and D4R (Sokoloff and Schwartz., 1995). These receptors, however, share common signaling cascades, including inhibition of cAMP formation, regulation of ion channel activities, and stimulation of mitogenesis through the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (Sokoloff and Schwartz, 1995; Missale et al., 1998). Despite the discrete distribution of the D3R as compared with the D2R, both receptors were reported to be coexpressed in neurons of striatum (Gurevich and Joyce, 1999). Whether members of the D2-like receptor family fulfill distinct functional roles has not yet been satisfactorily addressed. Growing evidence suggests the involvement of various sets of signaling regulatory proteins like GRK and arrestins in D1R (Jiang and Sibley, 1999) and D2R desensitization (Itokawa et al., 1996; Ito et al., 1999; Iwata et al., 1999), but a modest contribution of these proteins for the D3R (Kim et al., 2001; Kabbani et al., 2002).

Identification of subtype-specific dopamine receptor-interacting proteins may provide important clues for the determination of the functional differences between dopamine receptors. To better understand the regulation of D2-like receptor signaling, trafficking, and specificity, we sought to identify D3R-interacting proteins by screening a rat brain cDNA library using the yeast two-hybrid system with the C-terminal tail of the D3R as bait, bringing to light a novel interaction of D3R with the PDZ (PSD95/Dig/ZO-1) domain-containing protein, GIPC (GAIP interacting protein, C terminus). This protein has previously been identified as an interacting protein for several transmembrane and membrane-associated proteins, including GAIP, a regulator of G protein signaling (De Vries et al., 1998), β1-adrenergic receptor (Hu et al., 2003), semaphorine M-SemF (Cai and Reed, 1999), glucose transporter GLUT1 (Bunn et al., 1999), tyrosine kinase receptors like the neurotrophin receptors Trk A and Trk B (Lou et al., 2001), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor (Booth et al., 2002), and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) receptor type III (Blobe et al., 2001). These studies suggest a possible role of GIPC in the regulation of vesicular trafficking (De Vries et al., 1998; Lou et al., 2002), receptor surface expression (Bunn et al., 1999; Wang et al., 1999; Blobe et al., 2001), or G protein signaling (De Vries et al., 1998; Lou et al., 2001; Booth et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2003).

In this study, we report for the first time, a subtypespecific interaction between GIPC and the D2R, D3R but not D4R. Evidence is provided that GIPC, when recruited by the D2R or D3R at the plasma membrane, reduced receptor signaling and increased receptor stability through their sequestration in sorting vesicles, away from degradation compartments. This mechanism may take part in the regulation of D2R and D3R activity, but not D4R.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids Constructs

C-terminus domains of the rat D2R (aa 433-444), D3R (aa 435-446), D4R (aa 372-385), D3R C-terminus mutants (D3ΔC; D3A442K; D3ΔLKI and D3ΔEFR), human GAIP (aa 207-217), and human TrkB juxtamembrane domain (aa 458-544) were inserted in-frame downstream of the B42 activation domain into pEG202 vector (OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD). GIPC mutants, i.e., the PDZ domain (aa 125-265), the ACP domain (aa 223-316), both domains (aa 125-316) or the N-terminus (aa 1-125) were constructed by PCR and subcloned into pJG4.5 downstream of the LexA domain (OriGene Technologies). The D3R C-terminus coding sequence was subcloned into pGEX-2TK (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology, Piscataway, NJ). GIPC was tagged (Xpress/His-GIPC) at its N-terminus with the two epitopes (Xpress and poly-histidine) from pcDNA3.1HisC (Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, CA). Rat D3R and mutant D3ΔC were subcloned either into pcDNA3.1Hygro or pRc/CMV (Invitrogen Corp.). Other D3R mutants were PCR-amplified and subcloned in pcDNA3.1Hygro. The human D3R, D2R short isoform and D4R were fluorescently tagged at their N-terminus with the Enhanced Green Fluorescent protein fused to the nicotinic receptor α7 subunit signal peptide (Weill et al., 1999) in the pCEP4 vector (Invitrogen Corp.) and pcDNA3.1hygro, respectively. GFPD3ΔC was engineered by PCR using a specific mutant primer lacking the C-terminus cysteine residue. Human D2R short isoform and rat D3R were tagged at their N-terminus by PCR with the c-myc epitope (EQKLISEEDL). All constructions were verified by automated nucleotide sequencing (Licor, Lincoln, NE).

Yeast Two-hybrid Screening

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed using the DupLex-A Two-Hybrid system kit (OriGene Technologies) and supplied yeast strain EGY48 harboring the reporter genes LEU1 and β-galactosidase under the control of upstream LexA binding sites. Transformants were grown upon selective medium and assayed for β-galactosidase to verify and quantify interactions between bait and prey by solid-support assay and liquid culture assay, respectively, with X-gal and o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as substrates, according to the Yeast Protocols Handbook from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). Relative binding to GIPC is measured as follows: (βgal units (βU)test - βUcrl)/(βUGAIP - βUcrl). One unit of βgal is defined as the amount that hydrolyzes 1 μmol of ONPG per min per cell. Sequences isolated from clones were compared with nucleotide sequence databases using BLAST searches.

Cell Culture and Transfections

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO), COS7, and HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) or alpha-modified Eagle's medium (αMEM, Life Technologies) for the latter, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air. Cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes at 50-80% confluency and transiently transfected using calcium phosphate coprecipitation for HEK293 cells (Wigler et al., 1977) or Superfect (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA) for CHO and COS7 cells. HEK/GIPC, HEK/GFPD2R, and HEK/GFPD3R cell lines were obtained by transfection with 10 μg pcDNA3.1HisC-GIPC, pcDNA3.1hygroGFPD2R, and pCEP4-GFPD3R, respectively. HEK/GFPD2R/GIPC and HEK/GFPD3R/GIPC cell lines were obtained by transfection of the HEK/GFPD2R or HEK/GFPD3R cell lines with 10 μg pcDNA3.1HisC-GIPC. Clones were selected by resistance to hygromycin or neomycin and screened for receptor expression by measuring [125I]iodosulpride binding or for GIPC expression by Western blotting with the anti-Xpress antibody (Invitrogen Corp.). D3R mRNA expression was examined by Northern blot as described (Sokoloff et al., 1990). GIPC expression was assessed by Northern blot and RT-PCR using a GIPC N-terminus (aa 1-366) PCR probe and specific primers, respectively.

GST Pull-down Assay

GST and GST-D3R-Ct fusion proteins were produced in Escherichia coli BL21 after induction with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h. Sonicated cells were incubated in 500 μl of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer containing 150 mM NaCl (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) with 1% n-octyl β-d-glucoside for 1 h and centrifuged at 45,000 × g for 30 min. Supernatants were incubated with 100 μl of glutathione-Sepharose beads (50% slurry, Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology) for 30 min and washed three times with 10 ml of ice-cold PBS. The immobilized fusion proteins were then incubated with 500 μl of cytosolic extracts (300 μg·ml-1) from Xpress/His-GIPC-transfected COS7 cells at 4°C for 1 h and washed three times with 10 ml of ice-cold PBS. Pellets were resuspended in SDS sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot using the anti-Xpress antibody (dil. 1:5000).

In Vitro Interaction

D3R-expressing COS7 cells (Bmax = 1 pmol·mg protein-1) were harvested in 500 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4), supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), sonicated, and centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Membranes from three confluent 10-cm culture plates were solubilized by incubation for 45 min at 4°C in 500 μl of 50 mM Na/Na2PO4, pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mg/ml digitonin, 10 mg/ml deoxycholate, 10 mM dithiothreitol plus protein inhibitor cocktail, followed by centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 40 min at 4°C. Ni2+-chelating Sepharose column (HisTrap, Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology) was loaded with 1 ml of cytosolic extracts from COS7 cells overexpressing Xpress/His-GIPC (300 μg·ml-1), rinsed with 10 ml of 10 mM imidazole buffer (20 mM phosphate, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.4-7.6), and subsequently loaded with 1 ml of solubilized D3R-expressing membranes from transfected COS7 cells (300 μg·ml-1). The flow-through was collected before extensive washes in 10 mM imidazole buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with 500 mM imidazole buffer and collected as 1-ml aliquots. Flow-through and elution fractions were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblots revealed with anti-Xpress (dil 1:5000) and anti-D3R antibody (dil 1:1000) as described (Diaz et al., 2000). After stripping, membranes were probed with the D3R antibody presaturated with 10 μg/ml its immunizing peptide (G15Y; Diaz et al., 2000). In an independent experiment, the column was saturated with 900 μg of D3R-Ct peptide (EFRKAFLKILSC) before loading solubilized D3R membrane samples.

Immunoprecipitation of Endogenous Proteins

Membrane and soluble fractions from rat striatum were separated by centrifugation after sonication. Membranes were extensively washed and solubilized in the digitonin-cholate mixture previously described and receptors labeled with [125I]iodosulpride (0.4 nM; Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology). Endogenous GIPC was immunoprecipitated with the anti-GIPC N19 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and protein-A Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology). GIPC-antibody complexes were extensively washed and incubated with iodo-labeled receptors for 2 h at 4°C. After centrifugation, the nonprecipitated receptors in the supernatant were assayed by filtration (Diaz et al., 2000).

In Situ Hybridization

The N-terminus region of GIPC (nucleotides 1-366) was subcloned into pGEM-4Z (Promega, Madison, WI). The D3R riboprobe corresponding to the sequence of the third intracellular loop of the receptor is described elsewhere (Sokoloff et al., 1990). α-33P labeling and in situ hybridization were performed as previously described (Diaz et al., 1995).

Binding Assays

Binding experiments on cell membrane fraction were performed using [125I]iodosulpride (0.1 nM) for D2R and D3R and [3H]spiperone (0.4 nM) for D4R, as previously described (Sokoloff et al., 1992; Sautel et al., 1995). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM eticlopride. Binding data were analyzed by the nonlinear regression curve-fitting program PRISM (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Protein concentration was estimated with the Coomassie protein assay reagent using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard.

cAMP Accumulation Assay

Cells were preincubated with 10 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine in αMEM for 25 min and treated with quinpirole in increasing concentrations for 10 min in the presence of 0.5 μM forskolin. The reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μl of ice-cold 0.1 M HCl. Cells were sonicated and cAMP accumulation was assayed with the Rianen [125I]cAMP radioimmunoassay kit (DuPont/NEN, Boston, MA).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were grown on collagen-coated cover slips and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde/PBS (pH 7.4) for 20 min at room temperature, washed twice in PBS/glycine buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and permeated for 20 min with 0.05% saponin while blocking in 10% fetal bovine serum/PBS. For the internalization assay, anti-myc antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was applied on living mycD2R- and mycD3R-transfected cells for 1 h before fixation, and detection of GIPC was performed after cell permeation. GIPC was labeled with the anti-Xpress antibody (dil 1:3000) in incubation buffer (0.1% BSA/PBS supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum). Subsequent detection was performed using either an Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibody (Interchim, Lyon, France, dil 1:100) for mycD2R, mycD3R, or a biotin-coupled secondary antibody (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA, dil 1:70) and CY3-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, dil 1:2000) for GIPC. To localize subcellular sequestration compartments, we used the following specific markers: an anti-CD71 antibody (Harlan Seralab, Loughborough, Leicestershire, United Kingdom; dil 1:10), an anti-P58K (Sigma, dil 1:50), an anticlathrin kindly provided by A. Schmidt (dil 1:50), an anti-EEA1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, dil 1:80), an anti-CD63 (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, dil 1:200), which were revealed with a CY3-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Molecular Probes, 1:200).

Animal and tissue preparations for immunohistochemistry were performed as previously described (Diaz et al., 2000). Rat brain frontal sections (10 μm) were rinsed in 0.1 M glycine/PBS after fixation with paraformaldehyde 2%, immersed in blocking solution (5% donkey serum, 0.4% BSA, 0.1% gelatin, and 0.1% Tween in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h and incubated for 48 h with the anti-D3R (dil. 1:5000) and anti-GIPC (dil. 1:500) antibodies in 5% donkey serum, and 0.05% Tween in TBS. The sections were alternatively incubated for 1 h with an anti-donkey-AlexA488 (dil. 1:500, Interchim) and an anti-rabbit biotin-conjugated (dil. 1:300, Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology) that was further coupled to Streptavidin-CY3 (Dil. 1:4000, Jackson ImmunoResearch). The sections were rinsed several times for 40 min in TBS containing 0.1% gelatin and 0.05% Tween-20 after each incubation and, as for cell cultures, mounted on glass slides using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence was captured using a laser scanning confocal image system (Leica, Deerfield, IL).

RESULTS

Critical D3R C-terminal Residues for Ligand Binding

Structural determinants in the C-terminal domain of various GPCR are critical to regulate receptor trafficking and function, like D1R through its interaction with the accessory protein DRiP78 (Bermak et al., 2001). To assess the role of D3R C-terminus domain in its receptor function, we transfected D3R mutants (D3ΔC, D3A442K, and D3ΔLKI) in COS7 cells and performed ligand-binding analysis with [125I]iodosulpride, a D2R/D3R radioligand (Table 1). Mutations of the D3R C-terminus sequence profoundly affected ligand-binding properties because D3R mutants showed reduced [125I]iodosulpride binding (up to 94%). This may reflect receptor instability or an expression defect. We further examined the pharmacological profile of D3R mutants. A mutant lacking the LKI motif (D3ΔLKI) displayed a 20-fold lower affinity for dopamine. In contrast the mutant devoid of its C-terminal cysteine residue (D3ΔC) and the mutant that has its lysine442 substituted by an alanine residue (D3A442K) displayed threefold higher affinities for dopamine (Table 1). To investigate the influence of the deletion of the C-terminus cysteine on receptor expression, we compared mRNAs expression levels of D3R and its D3ΔC mutant in transiently transfected COS7 cells as assayed by Northern blot with a D3R-specific probe. The expression level of D3ΔC mRNA was higher than wild-type D3R (unpublished data), suggesting that this mutation did not induce an expression defect. Thus, because the deletion of the D3R C-terminus cysteine decreased neither receptor mRNA expression nor its affinity for dopamine, this mutation might interfere with protein-protein interactions, suggesting a critical role for the D3R C-terminus in D3R function.

Table 1.

Ligand binding properties of D3R mutants

| D3R | D3ΔC | D3ΔLKI | D3A442K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [125I]iodosulpride binding (% of D3R) | 100 ± 2.3 | 29 ± 2.3 | 6 ± 2 | 34 ± 3.9 |

| Dopamine Ki (nM) | 18 ± 3 | 6.3 ± 2 | 388 ± 80 | 4.5 ± 2 |

| Nafadotride Ki (nM) | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | nd | nd |

Plasmids coding for D3R and its mutants were transiently transfected in COS7 cells, and ligand binding was measured with 0.1 nM [125I]iodosulpride. D3R and its mutants were also transiently expressed in HEK293 cells, and varying concentrations (10−10-10−6 M) of dopamine or nafadotride, a D2-like antagonist, were used to inhibit [125I]iodosulpride binding. Dissociation constants were obtained by the nonlinear regression curve-fitting program PRISM (GraphPad). (means ± SEM of data from three independent experiments). nd, not determined.

GIPC Interacted with D2R, D3R, But Not D4R

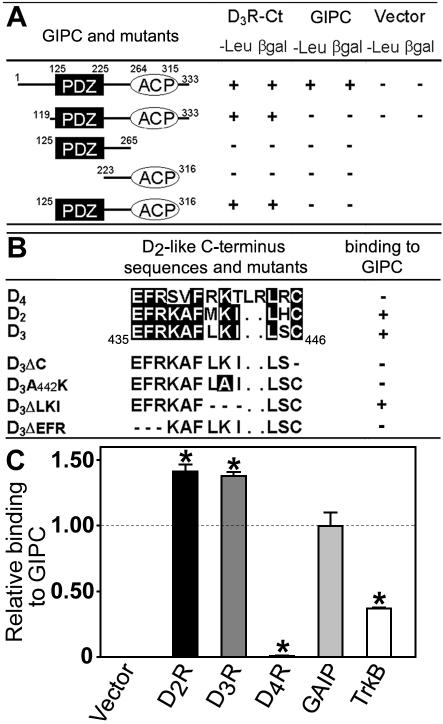

To identify proteins that interact with the D3R, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screening of a rat brain cDNA library using the D3R C-terminus cytoplasmic tail as bait. From 4.5 × 106 primary transformants screened, we isolated 50 colonies. Two of these clones coded for regions of rat GIPC. Sequence analysis revealed two conservative discrepancies (V252I and D270E) between these sequences and the published sequence of rat GIPC (De Vries et al., 1998). GIPC, mostly known as a PDZ (PSD95/Dlg/ZO-1) domain-containing protein (aa 125-225), displays two putative functional domains (Figure 1A), an acyl carrier protein domain (ACP) within the C-terminal region (aa 264-315), and a proline-rich N-terminal region (aa 1-56). The larger clone encoded the full-length open reading frame (ORF) of GIPC (aa 1-333), whereas the shorter contained the last two-thirds of the ORF (aa 119-333; Figure 1A). This suggests that the GIPC N-terminal domain did not take part in the interaction with the D3R C-terminus.

Figure 1.

Characterization of the interactions in the yeast two-hybrid system. (A) Cotransformants of the full-length GIPC cDNA (aa 1-333) or GIPC deletion mutants (including aa 119-333, aa 125-265, aa 223-316, aa 125-316) and the C-terminus of the D3R (D3R-Ct) or vector alone were screened for growth on leucine-deprived medium (-Leu) and β-galactosidase activity (βgal). Dimerization of GIPC was assessed in binary two-hybrid assays using GIPC cDNA as bait and prey. (B) For mapping of the GIPC binding site, D2R, D3R, and D4R C-termini and D3R C-terminus mutants were used in binary two-hybrid assays. +, interaction; -, no interaction. (C) The yeast strain EGY48 was cotransformed with the full-length GIPC cDNA and the putative interacting domains of the D2R, D3R, D4R, GAIP, and TrkB. The relative strength of protein-protein interactions observed in transformants was monitored by β-galactosidase liquid assay using ONPG as substrate. Binding to GIPC was compared with GAIP-GIPC interaction defined as 1. Values are means ± SEM of data from four experiments and two different transformations. *p < 0.01 versus GAIP-GIPC interaction.

To examine whether GIPC interacts with other dopamine D2-like receptors that are conserved at their C-termini (Figure 1B), we tested the D2R and D4R C-terminal domains in binary two-hybrid assays. GIPC interacted with D2R and D3R C-termini but not with that of the D4R (Figure 1B). This is in agreement with the fact that C-termini of D2R and D3R share a higher sequence identity than with the D4R. To compare the relative strength of interactions between GIPC and its various partners, we used a liquid phase assay of the two-hybrid system. Side-by-side comparisons of relative binding of several proteins to GIPC revealed a stronger interaction with dopamine receptor subtypes D2R and D3R than with the regulator of G protein signaling, GAIP, and the neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor type 2, TrkB (Figure 1C, p < 0.01). Taken together, our results indicate that the GIPC C-terminal region strongly interacts with D2R and D3R, but not with the D4R.

Characterization of the Mutual Interaction Domains

To localize the binding site of D3R on GIPC, each domain of GIPC was individually tested for its capacity to bind to the D3R C-terminus in binary two-hybrid assays. Whereas neither the PDZ nor the ACP domains alone were able to bind to the D3R C-terminus, the combination of both domains restored the interaction (Figure 1A). These observations suggest that the PDZ and ACP domains act together to carry out such an interaction. GIPC was also able to bind to itself through its N-terminal region (Figure 1A), suggesting a possible dimerization.

To delineate the GIPC target motif within the D3R C-terminus, D3R C-terminal mutants, constructed through site-directed mutagenesis, were used in binary two-hybrid assays with the full-length GIPC (Figure 1B, lower part). D2-like C-terminal sequences display a carboxy terminus type III PDZ-binding motif (X-X-CCOOH). Although interaction with GIPC was not only based on its PDZ domain as it also required the association of its ACP domain, removal of the D3R C-terminal cysteine residue (D3ΔC) abolished this interaction. However, this could not explain the subtype specificity of such an interaction, because the D4R also displays a C-terminal cysteine residue. Therefore, we next focused on residues outside the PDZ-binding motif. Removal of the EFR motif (D3ΔEFR) also abolished the interaction with GIPC (Figure 1B). In addition, the D3A442K mutant did not bind to GIPC contrary to the D3ΔLKI mutant, in which the loss of the LKI residues resulted in a shift of the K438 toward the PDZ-binding motif where it is in a position to compensate for the loss of the K442 (Figure 1B). This suggests that critical residues outside the PDZ-binding motif may carry out the interaction with GIPC together with the C-terminal cysteine residue. Moreover, the D4R C-terminal sequence contains two additional amino acids adjacent to its type III PDZ-binding motif compared with the D2R and D3R C-termini and may possess a different secondary structure of importance for receptor subtype GIPC-binding specificity. Taken together, these results indicate that specific interaction with GIPC required the C-terminal cysteine residue, which is part of the PDZ-binding motif, while other residues outside this motif likely ensure proper secondary structure of the receptor C-terminus.

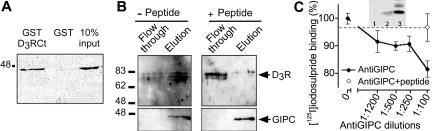

D3R and GIPC Interacted In Vitro

To verify the interaction between the D3R C-terminus and GIPC, we performed a pull-down assay (Figure 2A). GST and GST-D3R-Ct fusion protein expressed in E. coli were isolated on glutathione-Sepharose beads and incubated with lysates from COS7 cells transiently expressing Xpress/His-GIPC. Xpress/His-GIPC bound to GST-D3R-Ct, but not to GST.

Figure 2.

Interaction of GIPC with D2R and D3R. (A) GST and GST-D3R C-terminus fusion protein (GSTD3RCt) bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads, were incubated with extracts from COS7 cells overexpressing Xpress/His-GIPC. Bound proteins were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-Xpress antibody. (B) Binding of GIPC to the full-length D3R. Xpress/His-GIPC immobilized on an Ni2+-chelating column was incubated with solubilized D3R-containing membrane extracts from COS7 cells before extensive washes and elution with imidazole. Flow-through and elution fractions were analyzed by Western blot with anti-Xpress and anti-D3R antibodies. The experiment was performed without (left) or with (right) addition of an excess of the peptide EFRKAFLKILSC identical to D3R-Ct. (C) Endogenous GIPC interacts with D2R/D3R from rat striatum. Receptors from striatum were solubilized and labeled with [125I]iodosulpride, whereas endogenous GIPC from rat striatum was separately immunoprecipitated with anti-GIPC antibody in increasing concentrations, in the presence or absence of its immunizing peptide. Labeled receptors and immunopurified GIPC were incubated together and the nonprecipitated receptors were assayed (mean ± SEM of 5 determinations from 2 independent experiments and values are expressed as the percentage of immunoprecipitation with no anti-GIPC antibody). Inset: Western blot of immunoprecipitated GIPC from rat striatum.1, no antibody; 2 and 3, 1:500 and 1:100 dilutions, respectively.

To confirm the interaction with the full-length recombinant D3R, we performed affinity chromatography using an Xpress/His-GIPC construct bound onto a (poly)His-Trap column. Unbound proteins from D3R-transfected COS7 cells were collected in the flow-through, and bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by subsequent immunoblotting with an anti-Xpress antibody and a specific anti-D3R antibody (Diaz et al., 2000). D3R appeared on blot as typical 60-80-kDa species (Figure 2B), probably representing different glycosylation forms of the receptor (Diaz et al., 2000). D3R was retained on the column and coeluted with Xpress/His-GIPC (Figure 2B, left). In an independent experiment, the addition of an excess of a synthetic D3R C-terminal peptide, inhibited by 75% the interaction between Xpress/His-GIPC and D3R, of which immuno-reactivity was mostly detected in the flow-through (Figure 2B, right). Moreover, the D3R antibody presaturated with the immunizing peptide (G15Y, 10 mg/ml, Diaz et al., 2000) failed to produce any signal (unpublished data). These results provide biochemical evidence for an interaction between GIPC and mature and immature D3R.

Endogenous GIPC Interacted with D2R/D3R from Rat Striatum

To validate an interaction between endogenous proteins, an anti-GIPC antibody and [125I]iodosulpride to detect D2R/D3R binding sites from extracts of the rat striatum, were used. Solubilized D2R/D3R receptors were incubated with [125I]iodosulpride and the immunopurified GIPC-bound protein-ASepharose. Bound versus unbound proteins were separated by centrifugation, and the nonprecipitated receptors were assayed in the supernatant. Immunoprecipitation of GIPC with the anti-GIPC antibody was monitored by Western blot (Figure 2C, inset). GIPC from solubilized rat striatum was maximally immunoprecipitated with a 1:100 dilution of anti-GIPC antibody (lane 3), faintly with a 1:500 dilution (lane 2) but not without the use of the anti-GIPC antibody (lane 1). As shown in Figure 2C, solubilized D2R/D3R binding sites in the supernatant were depleted by immunopurified GIPC by up to 20%, depending on the dilution of the anti-GIPC antibody. This effect was almost abolished by presaturation of the anti-GIPC with an excess of its immunizing peptide, when the antibody was tested at the lowest dilution (1:100). Assaying the radioactivity retained on the GIPC-absorbed beads also showed, less reproducibly, that ∼19% of [125I]iodosulpride binding sites were immunoprecipitated with the lowest antibody dilution tested (1:100, unpublished data). These results support a physiological interaction between endogenous GIPC and D2R/D3R dopamine receptors from striatum.

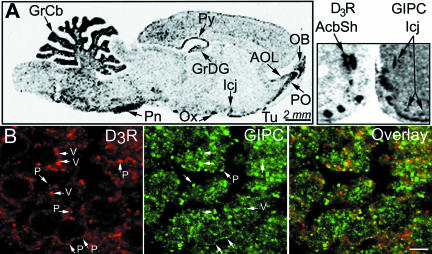

GIPC and D3R Colocalized in Rat Brain

To compare the localization patterns of GIPC and D3R mRNAs in the brain, we performed in situ hybridization with GIPC- and D3R-specific33P-labeled riboprobes on adjacent rat brain sections. GIPC displayed a widespread expression throughout the adult rat brain, yet with different hybridization signal intensities in various brain regions. Indeed, the expression level was higher in the granular layer of the cerebellum, pontine nuclei, granular layer of the dentate gyrus, olfactory tract, and cortex than in the striatum (Figure 3A). The addition of an excess of unlabeled GIPC riboprobe prevented signal detection in an adjacent section (unpublished data). Both D3R and GIPC mRNAs were observed in the nucleus accumbens and the islands of Calleja (Figure 3A), and coexpressed in the granular cells of the islands of Calleja wherein all cells expressed D3R mRNAs (Diaz et al., 1995).

Figure 3.

Distribution of GIPC and D3R in the rat brain. (A) In situ hybridization on a sagittal section with a33P-labeled GIPC riboprobe and frontal adjacent sections with33P-labeled D3R and GIPC riboprobes shown in mirror-image orientation. AOL, anterior olfactory nucleus, Acbsh, accumbens shell; lateral part; GrCb, granular layer of cerebellum; GrDG, granular layer of dentate gyrus; Icj, islands of Calleja; OB, olfactory bulb, PO, primary olfactory cortex; Py, pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus; PN, pontine nuclei; Ox, optic chiasm; Tu, olfactory tubercle. (B) Immunofluorescence on a 10-μm rat brain section with the anti-GIPC and anti-D3R antibodies revealed with an anti-donkey-AlexA488 and an anti-rabbit biotin-conjugated antibody that was further coupled to streptavidin-CY3. Arrows point to colocalization found in the granular cells in the islands of Calleja. P, plasma membrane; V, vesicles; Scale, 4 μm.

The overall distribution of GIPC protein, as assessed by immunohistochemistry, perfectly matched that of its mRNAs and was observed as a diffuse cellular and punctate labeling that was totally displaced by the addition of an excess of the immunizing peptide and absent when the anti-GIPC antibody was omitted (unpublished data). The D3R mainly localized to the plasma membrane and in vesicles, as suggested by the punctate distribution previously described (Diaz et al., 2000). The GIPC and D3R proteins partially colocalized in clusters at the plasma membrane (P) and in vesicles (V) in the granular cells of the islands of Calleja (Figure 3B, see arrows). These results support a physiological interaction between the two proteins in neurons in vivo.

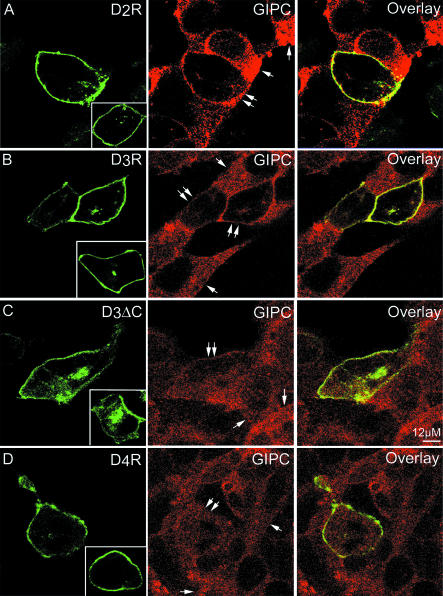

D2R, D3R, But Not D4R, Caused Translocation of GIPC to the Plasma Membrane

To further determine the subcellular site of the interaction between GIPC and dopamine receptors, we performed immunofluorescence studies. Wild-type HEK293 cells or stably expressing Xpress/His-GIPC (HEK/GIPC) were transiently transfected with GFPD2R, GFPD3R, or GFPD4R (Figure 4), which possess ligand-binding characteristics similar to that of wild-type receptors (unpublished data). In HEK/GIPC cells devoid of detectable dopamine receptor subtypes expression, GIPC was diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm (Figure 4, arrows). On single transfection in HEK293 and HEK/GIPC cells and under determined conditions, i.e., low amount of transfected DNA (<0.1 μg/well of a 12-well plate) and examination shortly after transfection (24 h), GFP-tagged receptors were prominently expressed at the plasma membrane (Figure 4, A and B, insets). GIPC translocated to the plasma membrane and colocalized with D2R or D3R in cells transiently expressing these receptors (Figures 4, A and B, double arrows). However, GIPC translocation to the plasma membrane was less efficient when transiently overexpressed in HEK293 cells stably expressing dopamine receptors (unpublished data). To confirm that this effect resulted from a direct interaction between GIPC and the D2R or D3R, we used GFPD4R and the GFPD3ΔC mutant, which does not to interact with GIPC. In HEK293 and HEK/GIPC cells, GFPD3ΔC was expressed at the plasma membrane, but also more readily in intracellular compartments than GFPD3R (Figure 4C, inset), which may explain the reduction of D3ΔC ligand binding (Table 1). Moreover, GFPD4R and GFPD3ΔC did not cause any GIPC translocation (Figures 4, C and D, double arrows). In addition, mutation of GIPC in its D3R-binding site by deletion of its ACP domain resulted in a distribution similar to that of the wild-type GIPC, but a complete loss of its translocation and colocalization with the D3R upon cotransfection (unpublished data). These data show that, through a direct interaction, the D2R and D3R are able to recruit GIPC at the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

D2R-, D3R-dependent translocation of GIPC to the plasma membrane. HEK293 and HEK/GIPC cell lines were transiently transfected with cDNAs encoding for GFPD2R (A), GFPD3R (B), GFPD3ΔC (C), or GFPD4R (D). CY3-labeled Xpress antibody for GIPC and GFP fluorescence were observed by confocal microscopy. For comparison, cells expressing receptors but not GIPC are shown in insets. Arrows show cells expressing GIPC alone and double arrows show cells coexpressing GIPC and a dopamine receptor subtype.

GIPC Affected a D3R-mediated Response

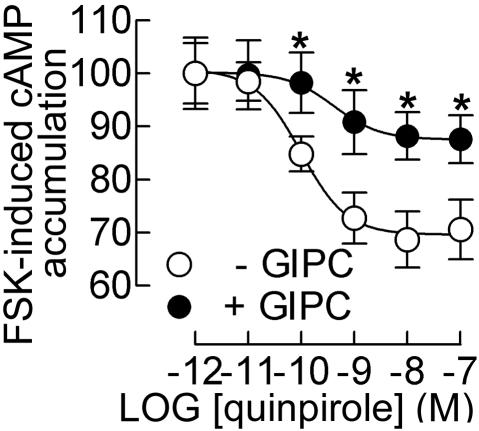

Because D3R provokes a massive translocation of GIPC to the plasma membrane, the question arose as to whether GIPC could affect agonist-induced D3R signaling. To address this question, we first developed a cell line stably expressing the human D3R (GFPD3R), which was subsequently transfected with GIPC. In HEK293 cells, D3R stimulation by the D2-like agonist, quinpirole (LY), inhibited cAMP accumulation triggered by forskolin (0.5 μM) in a concentration-dependent manner, with an EC50 of 0.11 ± 0.02 nM (mean ± SEM) and a maximal inhibition of 31 ± 0.6% (Figure 5). The overexpression of GIPC reduced the maximal inhibition of cAMP accumulation by forskolin after D3R stimulation to 12 ± 0.3% (p < 0.01) with a significant rightward shift in the dose-response curve (EC50 = 0.42 ± 0.06 nM, p < 0.01; Figure 5). This result suggests a role of GIPC in the negative regulation of the D3R signaling.

Figure 5.

GIPC reduces D3R-mediated response. Inhibition of cAMP accumulation by quinpirole (LY) in increasing concentrations in HEK/GFPD3R and HEK/GFPD3R/GIPC cell lines in the presence of 0.5 μM forskolin (FSK). Results are expressed as a percentage of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation and are means ± SEM of data from seven independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus + GIPC.

D2R, D3R, But Not D4R, Cointernalized with GIPC

PDZ proteins have previously been shown to regulate receptor internalization, so we investigated the effect of GIPC on such a process in HEK/GIPC cells transiently transfected with extra-cellular epitope-tagged receptors (mycD2R, mycD3R, and GFPD4R). We used GFPD4R instead of mycD4R in these experiments, because mycD4R did not readily internalize upon activation. To detect receptors at the cell surface and those internalized upon quinpirole (LY) stimulation, we applied the anti-myc antibody on living mycD2R- and mycD3R-transfected cells, as this antibody did not induce, by itself, receptor internalization (unpublished data). To properly distinguish internalized from newly synthesized D4R, we used the previously determined experimental conditions, in which the receptors are prominently expressed at the plasma membrane. On stimulation with quinpirole, D2R, D3R, and D4R receptors internalized with different kinetics, rapid and strong for D2R and D4R after a 30 min-exposure to 2 μM and 5 μM quinpirole (LY), respectively (unpublished data). In contrast, exposure to 2 μM quinpirole for 1 h induced a low extent of internalization of the D3R with a slower kinetic rate than that of the D2R (unpublished data). GIPC partially colocalized with D2R-labeled vesicles upon stimulation with quinpirole for 1 h (Figure 6A) and strictly cotrafficked with D3R from the plasma membrane to endocytotic vesicles (Figure 6B), an effect blocked in the presence haloperidol (50 μM), a D2-like antagonist (unpublished data). Unlike D2R and D3R, D4R-labeled endocytotic vesicles were never labeled with the anti-GIPC antibody (Figure 6C). Thus, GIPC cointernalized with D2R, D3R but not D4R. The nonexhaustive labeling of D2R-labeled vesicles with GIPC may suggest that it is subsequently released during vesicular sorting.

Figure 6.

Cointernalization of GIPC with the D2R, D3R but not the D4R. HEK/GIPC cells were transiently transfected with mycD2R (A), mycD3R (B), and GFPD4R (C) cDNAs and stimulated by quinpirole (LY), a D2-like agonist (2 μM for D2R and D3R, and 5 μM for D4R) for 1 h. The anti-myc antibody was added on living cells, which were subsequently fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with the anti-Xpress antibody. Anti-myc and Xpress antibodies were revealed with secondary antibodies coupled to Alexa488 and CY3, respectively, the D4R was detected by the GFP fluorescence and visualized by confocal microscopy.

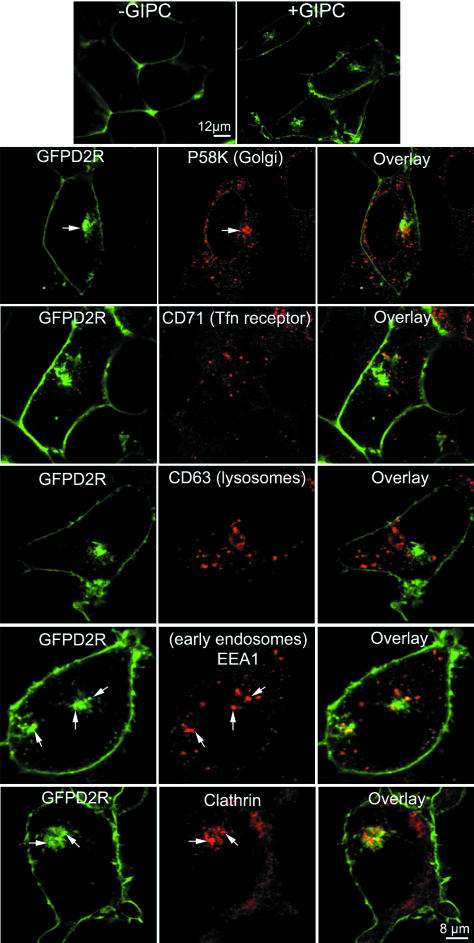

GIPC Altered Plasma Membrane Localization of the D2R

To investigate the function associated to the persistent interaction between GIPC and the internalized D2R and D3R, we focused on receptor trafficking and sorting. GFPD2R localized strictly to the plasma membrane, when stably expressed in HEK293 cells (Figure 7, top panel, left), although its transient expression resulted in faint labeling in the Golgi apparatus (Figure 4). In contrast, when stably coexpressed with GIPC, GFPD2R partially localized in vesicles (Figure 7, top panel, right), as observed with GFPD3R (unpublished data). To identify the nature of these vesicles, we performed immunocytochemistry with several biomarkers. Receptor-bearing vesicles were different from recycling vesicles where the transferrin receptor CD71 constitutively traffics, and lysosomes as revealed by the marker CD63 (Figure 7). However, vesicles partially colocalized with the Golgi apparatus marker P58K, the early endosome marker EEA1 and clathrin-coated vesicles (Figure 7). These results suggest that GIPC altered D2R and D3R subcellular localization independently of receptor activation by either redistributing or sequestrating receptors in sorting vesicles.

Figure 7.

GIPC induces D2R sequestration in endosomes. HEK/GFPD2R (top panel, left) and HEK/GFPD2R/GIPC (top panel, right) cells were seeded on glass cover slips, fixed, and permeabilized before subsequent detection of the different subcellular markers. Markers were all revealed with a CY3-conjugated anti-mouse antibody and GFP fluorescence visualized by confocal microscopy. The following markers, CD71, CD63, P58K, EEA1, labeled the transferrin receptor, lysosomes, the Golgi apparatus, and early endosomes, respectively.

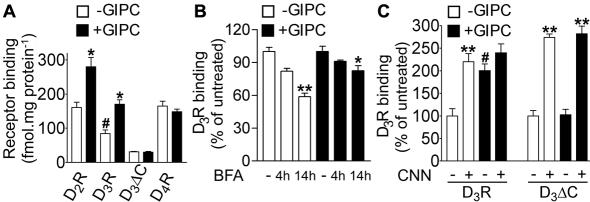

GIPC Increased the Number of D2R and D3R Binding Sites

To further test the above mentioned possibilities, we studied the effect of GIPC on the expression of the D2-like receptors by assaying [125I]iodosulpride binding to the wild-type recombinant D2R and D3R, and [3H]spiperone binding to the wild-type recombinant D4R using HEK293 and HEK/GIPC cells that were transiently transfected with the D2R, D3R, D3ΔC, or D4R. Receptor overexpression was allowed for 48 h posttransfection and followed by ligand-binding studies on total cell membrane preparations to include receptors at the cell surface and in vesicles. [125I]iodosulpride binding was 75-100% higher when D2R or D3R was transfected in HEK/GIPC cells than in HEK293 cells, whereas no effect of GIPC on either D3ΔC that has reduced ligand binding (Table 1) or D4R binding could be noted (Figure 8A). A similar but reduced effect (+30%) was found when Xpress/His-GIPC was transiently transfected in HEK293 cells stably expressing either D3ΔC or D3R and CHO cells stably expressing either D2R, D3R, or D4R (unpublished data). In fact, GIPC increased the maximal number of D3R expressed (Bmax = 721 ± 35 vs. 589 ± 39 fmol·mg protein-1, p < 0.05), without any change in [125I]iodosulpride binding affinity (Kd = 1.2 ± 0.015 vs. 1.197 ± 0.06 nM; unpublished data). Moreover, GIPC overexpression did not affect mRNA levels of heterologous D3R as assessed by Northern blot analysis (unpublished data), suggesting that elevated receptor expression was a consequence of protein stabilization. These results establish that GIPC specifically increased D2R and D3R protein expression in virtue of its direct interaction with the two receptors by their sequestration during biosynthesis, processing, or degradation.

Figure 8.

GIPC affects D2R, D3R ligand binding and prevents D3R vacuolar degradation. (A) [125I]iodosulpride (0.1 nM) binding for the D2R and D3R and [3H]spiperone (0.4 nM) for the D4R in HEK293 and HEK/GIPC cell lines transiently transfected with pCMV-mycD2R, pCMV-D3R, pCMV-D3ΔC, or pCMV-D4R. Values are the mean ± SEM of data from four experiments. #p < 0.05 versus D3ΔC; **p < 0.05 versus -GIPC. (B) Effect of brefeldin A (BFA), an ER-to-Golgi protein translocation inhibitor, on D3R binding in HEK293 (open columns) or HEK/GIPC (filled columns) transiently transfected with pCMV-D3R. Values are expressed as percentage of untreated cells and are means ± SEM of data from four experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 versus untreated cells. (C) Effect of concanamicyn A (CNN), a vacuolar protein degradation inhibitor, incubated for 14 h, on D3R and D3ΔC binding in HEK293 (open columns) or HEK/GIPC (filled columns) transiently transfected with pCMV-D3R and pCMV-D3ΔC. Values are expressed as percentage of untreated cells and are means + SEM of data from three experiments, **p < 0.01 versus untreated cells,#p < 0.01 versus untreated cells-GIPC.

GIPC Did Not Interfere with D3R Maturation

Previous data (Liu et al., 2001) showed that only newly synthesized tyrosinase-related protein-1 (TRP-1) associates with GIPC, primarily in the juxtanuclear Golgi region to help its biosynthetic sorting. Having found that GIPC interacted with the different D3R maturation forms (Figure 2B) together with the fact that stably expressed GIPC translocated better at the plasma membrane with D2R and D3R (Figure 4) than transiently expressed GIPC (unpublished data), we hypothesized that interaction with GIPC establishes during receptor maturation. To block the trafficking of newly synthesized D3R and thus their maturation, we used brefeldin A (BFA), an endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi apparatus protein translocation inhibitor. Indeed, in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with D3R, treatment with BFA resulted in a time-dependent decrease of [125I]iodosulpride binding, reaching 40% after 14 h (Figure 8B) as the cellular pool of receptors is depressed by degradation (Fukuchi et al., 1986). However, when measured in HEK/GIPC cells transiently transfected with D3R, the decrease of [125I]iodosulpride binding observed after BFA treatment was limited to <15% (Figure 8B), suggesting that GIPC still increased receptor binding despite treatment by stabilizing receptors on postmaturation.

GIPC Prevented D3R Degradation

To examine whether GIPC prevented D3R degradation as a possible explanation for GIPC-induced receptor sequestration, we assayed the effect of GIPC on receptor ligand binding in the presence of a set of degradation inhibitors containing the proteasome inhibitor I, a blocker of chymotrypsin-like activity; MG132, a potent reversible inhibitor of the 26-S proteasome; lactacystin, a specific irreversible inhibitor of the 20-S proteasome; and concanamicyn A (CNN), which inhibits acidification of organelles as in lysosomes and the Golgi apparatus (Woo et al., 1992). In HEK293 cells transiently expressing the D3R, a 14-h incubation with the proteasome inhibitors had no effect on D3R degradation (unpublished data), indicating that this pathway was not required. On the contrary, CNN treatment increased by 130% the number of D3R and D3ΔC binding sites (Figure 8C), suggesting that D3R degradation, as that of many GPCRs, required the vacuolar proteolytic pathway. In HEK/GIPC cells transiently transfected with the D3R, [125I]iodosulpride binding was twice as high as in wild-type HEK293 cells and CNN did not significantly increase D3R expression (Figure 8C). In contrast, CNN increased D3ΔC binding in HEK/GIPC cells. Thus the effect GIPC on D3R expression is not synergistic with CNN because GIPC mimicked the effect of CNN by inhibiting receptor degradation. These results support the role of the endosomal or lysosomal compartments in regulating D3R expression and suggest that GIPC, via its direct interaction with D3R but not with D3ΔC, protects receptors from degradation, probably preventing vesicular sorting to lysosomes.

DISCUSSION

An important functional role for the cytoplasmic C-terminus of D3R, which served as bait in the yeast two-hybrid screening, was initially suggested by the high conservation of this domain within the D2-like receptors. The crystal structure of rhodopsin, a prototypical GPCR, predicts that its C-terminal domain exists as an amphipathic helix anchoring this domain at the intracellular face of the membrane. These results show that several mutations in the D3R C-terminal domain produced a dramatic reduction of ligand binding, suggesting that it confers a proper conformation to the ligand-binding pocket or binds the receptor to regulatory cytoplasmic partners (Bermak et al., 2001; Xiang et al., 2002). For instance, a D3R mutant that lacks its C-terminal cysteine, D3ΔC, displayed reduced ligand binding, but quite an intact pharmacological profile, suggesting that the mutation may have impaired receptor trafficking and/or maturation. In agreement with a role for GIPC in these latter function, D3ΔC did not interact with GIPC. The interaction of GIPC with both D2R and D3R seems to involve an unusual mode of PDZ recognition (Harris et al., 2001), because both receptors have a PDZ type III consensus motif X-X-C (Harris and Lim, 2001) at their C-terminus, whereas most GIPC-interacting proteins binding sites match the PDZ type I consensus motif S/T-X-V/A/L/I (De Vries et al., 1998; Hu et al., 2003). Moreover, both the PDZ and ACP domains of GIPC were required to interact with D3R. Although the necessity of the ACP domain could have resulted from instability or improper folding of the PDZ domain fusion protein in yeast, previous studies have shown that the ACP domain of Kermit, the GIPC Xenopus homologue, is also required to interact with frizzled 3, a receptor for the Wnts, and with neuropilin 1, a receptor for Semaphorin III (Cai and Reed, 1999; Tan et al., 2001). In addition, GIPC binds to an internal motif of the TrkB receptor although interaction is less potent with an internal than a C-terminal PDZ-binding consensus. The interactions of GAIP and TrkA are based on two distinct sites in the PDZ domain of GIPC (Lou et al., 2001), highlighting the plasticity of the PDZ-based recognition by GIPC. Thus, the conformation of the whole cytoplasmic tail might also be of crucial importance because the D4R C-terminus, which displays the X-X-C motif, but is two amino acids longer than that of D2R and D3R, did not bind to GIPC. Hence, whereas PDZ domain specificity is primarily determined by the chemical nature of the last and third from last residues of the PDZ-binding consensus sequence (Harris et al., 2001), amino acids that are crucial for the structural integrity of the hairpin required for interaction with the PDZ domain are at least as important as residues making direct contacts.

Scaffolding proteins usually have multiple PDZ domains, contrary to GIPC, which has a single PDZ domain. Nevertheless, GIPC is able to interact with itself through its N-terminus region to form homo-oligomers, thus containing multiple PDZ-binding sites permitting the formation of macro-molecular multicomplexes. Hence, GIPC possesses structural and functional characteristics favorable to its role as a scaffold protein, believed to be involved in organizing and assembling protein complexes by spatially clustering cytosolic proteins, which are usually components of signal transduction pathways of transmembrane receptors or channels (Li and Montell, 2000; Hamazaki et al., 2002).

Although GIPC mRNA is known to be highly expressed in the brain, its distribution among brain regions at the cellular level was previously unknown (De Vries et al., 1998; Bunn et al., 1999). Here GIPC mRNAs were found to be enriched in several brain regions, including the granular layer of cerebellum and dentate gyrus, pontine nuclei, olfactory tract, and cortex. Such an ubiquitous distribution for GIPC is consistent with the variety of its ascribed binding targets. Furthermore, expression of GIPC mRNAs in the rat brain strictly matched that of its protein counterpart, and the GIPC and D3R mRNAs and proteins colocalized in neurons of the islands of Calleja. Not only do these anatomical studies support the formation of a GIPC/D3R complex in vivo, but an antibody directed toward GIPC immunoprecipitated D2R/D3R from the striatum. Collectively, these results show that GIPC and dopamine receptors are found in close association in neurons, which supports the physiological relevance of their interaction.

In neurons and cell cultures, GIPC protein was detected as a diffuse cellular and punctate staining typical of vesicular localization, which is consistent with the identification of distinct soluble and membrane-based pools (Lou et al., 2002). However, when coexpressed with D2R or D3R independently of receptor activation, GIPC massively translocated from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane as previously described for the Xenopus GIPC homologue (Tan et al., 2001). This effect likely resulted from a direct interaction, because a D3R mutant or the wild-type D4R, neither of which bound to GIPC in the yeast two-hybrid system, were unable to recruit GIPC at the plasma membrane. Such an effect may reflect clustering of cytosolic proteins coupled to signal transduction. Accordingly, GIPC reduced both the maximal inhibition of forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation, a typical D3R-mediated response (Griffon et al., 1997) and quinpirole potency to evoke this response. Our results suggest a role of GIPC in D3R signaling, by reducing its transduction via Giα/Goα, which are preferentially coupled to D2-like receptors. In agreement, it was shown that GIPC regulates the β1-adrenergic receptor-mediated, Giα-dependent ERK activation (Hu et al., 2003). Because GIPC binds to GAIP, a regulator of G protein signaling that serves as GTPase-activator for Giα and Gqα subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins (De Vries et al., 1995), we hypothesize that GIPC, GAIP, and the D3R form a multimeric complex. According to this hypothesis, GIPC might constitute a physical link between the two other components, to turn off Giα and then act negatively on D3R signaling. The function of GIPC would be to promote GAIP-mediated Giα-GTP hydrolysis that terminates the G protein signal and recycles the resulting Giα-GDP for another round of G protein activation. Such an effect would result in termination of the receptor transduction cascade. Further studies are needed to directly demonstrate the formation of a GPCR/GIPC/GAIP multimeric complex. At this stage, it can be hypothesized that the subtype specificity of interacting proteins, as the suggested interaction of GIPC with D2R, D3R, but not D4R, may be relevant to receptors sharing a common signaling pathways, such as the D2-like receptors.

Agonist-induced GPCR signaling is rapidly downregulated through receptor phosphorylation by GRK, followed by arrestin binding leading to receptor internalization (Claing et al., 2002). GIPC could take part in such a multiprotein scaffolding complex. However, little effect of GIPC on agonist-induced D3R internalization was found (unpublished data), which is consistent with previous observations concerning the β1-adrenergic receptor (Hu et al., 2003). Although GIPC had no effect on receptor endocytosis, it cointernalized with D2R or D3R, which is consistent with the association of GIPC in clathrin-coated pits and clathrin-coated vesicles (Lou et al., 2002). Colocalization of GIPC with receptors in endocytotic vesicles, after a prolonged agonist stimulation, was complete with D3R and partial with D2R, suggesting the possible dissociation of GIPC-receptor complexes in sorting vesicles. Such discrepancies probably reflect different internalization kinetics, rapid for the D2R and slow for the D3R (unpublished data). Such a persistent interaction with D2R and D3R could reflect other functional roles for GIPC, such as in assisting receptor trafficking after its internalization. Indeed, GIPC promoted agonist-independent sequestration of D2R in early endosomes and clathrin-coated vesicles, thus providing protection of receptors against degradation. As expected for a GPCR, the vacuolar route is mainly involved in D3R degradation. Nevertheless, GIPC may exert its protective effect independently of the degradation route, because it also protects the TGFβ type III receptor from ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated degradation (Blobe et al., 2001). It is noteworthy that overexpression of the GIPC-binding partner, GAIP, by stimulating GTPase activity of Gi3α, regulates autophagic sequestration and thus degradation (Ogier-Denis et al., 1997). The GIPC-mediated receptor stabilization may reflect GIPC interaction with cytoskeletal-binding proteins, such as α-actinin1, or cytoskeletal motors, such as kinesin KIF1B and myosin VI (Bunn et al., 1999). Recent data demonstrated that myosin VI is recruited on GIPC-coated vesicles to promote vesicular trafficking of nascent endocytotic vesicles to early endosomes (Aschenbrenner et al., 2003).

In summary, depending on the cytoplasmic effectors recruited, the stable and selective interaction with scaffold protein GIPC may exert distinct roles to assist receptor functions, i.e., signaling, trafficking, and sorting. Indeed, through dimerization, GIPC may alternatively recruit either RGS or cytoskeleton-associated proteins (Bunn et al., 1999) to uncouple the D2R and D3R from their signaling cascade and to subsequently link the receptor to the cytoskeleton, leading to receptor sequestration in vesicles and protection against degradation. The mechanism described here could represent a previously unrecognized process of regulation of the D2R and D3R, and possibly other GPCRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Betz, O. El Far, and S. Kins for advice in two-hybrid system; F. Prieur for technical assistance; J.L. Galzi and S. Morisset for help with the GFP-D3R construct; F. Coumailleau for technical support in immunofluorescence; and T. Ouimet and A. Parker for critical reading and editing the manuscript.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0293. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0293.

Abbreviations used: aa, amino acids; Ct, C-terminus; D2R, D3R and D4R, dopamine D2, D3, and D4 receptors; GAIP, Gαi3 interacting protein; GIPC, GAIP-interacting protein C-terminus; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; GRK, G protein-coupled receptor kinase; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HEK293, embrionic kidney cells; PDZ, consensus sequence in PSD95/DLG/zo-1; RGS, regulator of G protein signaling.

References

- Aschenbrenner, L., Lee, T.T., and Hasson, T. (2003). Myo6 facilitates the translocation of endocytotic vesicles from cell peripheries. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 2728-2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermak, J.C., Li, M., Bullock, C., and Zhou, Q-Y. (2001). Regulation of transport of the D1 receptor by a new membrane-associated ER protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 492-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobe, G.C., Liu, X., Fang, S.J., How, T., and Lodish, H.F. (2001). A novel mechanism for regulating transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling. Functional modulation of type III TGF-β receptor expression through interaction with the PDZ domain protein, GIPC. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39608-39617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, S.K., Grady, E.F., and Bunnett, N.W. (1997). Regulatory mechanisms that modulate signalling by G protein-coupled receptors. Biochem. J. 322, 1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth, R.A., Cummings, C., Tiberi, M., and Liu, X. (2002). GIPC participates in G protein signaling downstream of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6719-6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn, R.C., Jensen, M.A., and Reed, B.C. (1999). Protein interactions with the glucose transporter binding protein GLUT1CBP that provide a link between GLUT1 and the cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 819-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H., and Reed, R.R. (1999). Cloning and characterization of neuropilin-1-interacting protein: a PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 domain-containing protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of neuropilin-1. J. Neurosci. 19, 6519-6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claing, A., Laporte, S.A., Caron, M.G., and Lefkowitz, R.J. (2002). Endocytosis of G protein-coupled receptors: roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and beta-arrestin proteins. Prog. Neurobiol. 66, 61-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, L., Lou, X., Zhao, G., Zheng, B., and Farquhar, M.G. (1998). GIPC, a PDZ domain containing protein, interacts specifically with the C terminus of RGS-GAIP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12340-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, L., Mousli, M., Wurmser, A., and Farquhar, M.G. (1995). GAIP, a protein that specifically interacts with the trimeric G protein G alpha i3, is a member of a protein family with a highly conserved core domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11916-11920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, J., Lévesque, D., Lammers, C.H., Griffon, N., Martres, M.-P., Schwartz, J.-C., and Sokoloff, P. (1995). Phenotypical characterization of neurons expressing the dopamine D3 receptor. Neuroscience 65, 731-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, J., Pilon, C., Le Foll, B., Gros, C., Triller, A., Schwartz, J.-C., and Sokoloff, P. (2000). Dopamine D3 receptors expressed by all mesencephalic dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 20, 8677-8684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, S. (2001). Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: the role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol. Rev. 53, 1-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi, I., Fujita, N., Nakahiro, M., Saito, K., and Yoshida, H. (1986). D-2 dopamine receptor synthesis and turnover in rat striatum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 127, 291-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffon, N., Pilon, C., Sautel, F., Schwartz, J.-C., and Sokoloff, P. (1997). Two intracellular pathways for the dopamine D3 receptor: opposite and synergistic interactions with cyclic AMP. J. Neurochem, 68, 1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich, E.V., and Joyce, J.N. (1999). Distribution of dopamine D3 receptor expressing neurons in the human forebrain. Neuropsychopharmacology 1, 60-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki, Y., Itoh, M., Sasaki, H., Furuse, M., and Tsukita, S. (2002). Multi-PDZ domain protein 1 (MUPP1) is concentrated at tight junctions through its possible interaction with claudin-1 and junctional adhesion molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 455-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, B.Z., Hillier, B.J., and Lim, W.A. (2001). Energetic determinants of internal motif recognition by PDZ domains. Biochemistry 40, 5921-5930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, B.Z., and Lim, W.A. (2001). Mechanism and role of PDZ domains in signaling complex assembly. J. Cell Sci. 114, 3219-3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.A., Chen, W., Martin, N.P., Whalen, E.J., Premont, R., and Lefkowitz, R.J. (2003). GIPC interacts with the beta 1-adrenergic receptor and regulates beta 1-adrenergic receptor mediated ERK activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26295-26301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, K., Haga, T., Lameh, J., and Sadee, W. (1999). Sequestration of dopamine D2 receptors depends on coexpression of G protein-coupled receptor kinases 2 or 5. Eur. J. Biochem. 260, 112-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itokawa, M., Toru, M., Ito, K., Tsuga, H., Kameyama, K., Haga, T., Arinami, T., and Hamaguchi, H. (1996). Sequestration of the short and long isoforms of dopamine D2 receptors expressed in CHO cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 49, 560-566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, K., Ito, K., Fukuzaki, A., Inaki, K., and Haga, T. (1999). Dynamin and rab5 regulate GRK2-dependent internalization of dopamine D2 receptors. Eur. J. Biochem. 263, 596-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D., and Sibley, D.R. (1999). Regulation of D(1) dopamine receptors with mutations of protein kinase phosphorylation sites: attenuation of the rate of agonist-induced desensitization. Mol. Pharmacol. 56, 675-683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani, N., Negyessy, L., Lin, R., Goldman-Rakic, P., and Levenson, R. (2002). Interaction with neuronal calcium sensor NCS-1 mediates desensitization of the D2 dopamine receptor. J. Neurosci. 22, 8476-8486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.M., Valenzano, K.J., Robinson, S.R., Yao, W.D., Barak, L.S., and Caron, M.G. (2001). Differential regulation of the dopamine D2 and D3 receptors by G protein-coupled receptor kinases and beta-arrestins. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37409-37414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno, T., Wada, A., and Igarashi, Y. (2002). N-glycans of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor Edg-1 regulate ligand-induced receptor internalization. FASEB J. 16, 983-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.S., and Montell, C. (2000). TRP and the PDZ protein, INAD, form the core complex required for retention of the signalplex in Drosophila photoreceptor cells. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1411-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.F., Kandala, G., and Setaluri, V. (2001). PDZ domain protein GIPC interacts with the cytoplasmic tail of melanosomal membrane protein gp75 (tyrosynase-related protein-1). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35768-35777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou, X., McQuistan, T., Orlando, R.A., and Farquhar, M.G. (2002). GAIP, GIPC and Galphai3 are concentrated in endocytotic compartments of proximal tubule cells: putative role in regulating megalin's function. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 918-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou, X., Yano, H., Lee, F., Chao, M.V., and Farquhar, M.G. (2001). GIPC and GAIP form a complex with TrkA: a putative link between G protein and receptor tyrosine kinase pathways. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 615-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J.N., Kozell, L.B., and Neve, K.A. (2002). Regulation of dopamine D(1) receptor trafficking by protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation. Mol. Pharmacol. 61, 806-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale, C., Nash, S.R., Robinson, S.W., Jaber, M., and Caron, M.G. (1998). Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 78, 189-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogier-Denis, E., Petiot, A., Bauvy, C., and Codogno, P. (1997). Control of the expression and activity of the Galpha-interacting protein (GAIP) in human intestinal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24599-24603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautel, F. et al. (1995). Nafadotride, a potent preferential dopamine D3 receptor antagonist,. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 3, 1239-1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, P., Andrieux, M., Besançon, R., Pilon, C., Martres, M.-P., Giros, B., and Schwartz, J.-C. (1992). Pharmacology of human D3 dopamine receptor expressed in a mammalian cell line: comparison with D2 receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Mol. Pharmacol. Sect. 225, 331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, P., Giros, B., Martres, M.-P., Bouthenet, M.-L., and Schwartz, J.-C. (1990). Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature 347, 146-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, P., and Schwartz, J.-C. (1995). The novel dopamine receptors half a decade later. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 16, 270-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C., Deardorff, M.A., Saint-Jeannet, J.P., Yang, J., Arzoumanian, A., and Klein, P.S. (2001). Kermit, a frizzled interacting protein, regulates frizzled 3 signaling in neural crest development. Development 128, 3665-3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.H., Kalb, R.G., and Strittmatter, S.M. (1999). A PDZ protein regulates the distribution of the transmembrane semaphorin, M-SemF. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14137-14146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weill, C., Ilien, B., Goeldner, M., and Galzi, J.L. (1999). Fluorescent muscarinic EGFP-hM1 chimeric receptors: design, ligand binding and functional properties. J. Recept. Signal. Transduct. Res. 19, 423-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigler, M., Silverstein, S., Lee, L.S., Pellicer, A., Cheng, Y.C., and Axel, R. (1977). Transfer of purified herpes virus thymidine kinase gene to cultured mouse cells. Cell 11, 223-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.T., Shinohara, C., Sakai, K., Hasumi, K., and Endo, A. (1992). Inhibition of the acidification of endosomes and lysosomes by the antibiotic concanamycin B in macrophage J774. Eur. J. Biochem. 207, 383-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y., Devic, E., and Kobilka, B. (2002). The PDZ binding motif of the beta 1 adrenergic receptor modulates receptor trafficking and signaling in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33783-33790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., Barak, L.S., Winkler, K.E., Caron, M.G., and Ferguson, S.S. (1997a). A central role for beta-arrestins and clathrin-coated vesicle-mediated endocytosis in beta2-adrenergic receptor resensitization. Differential regulation of receptor resensitization in two distinct cell types. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27005-27014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., Ferguson, S.S., Barak, L.S., Aber, M.J., Giros, B., Lefkowitz, R.J., and Caron, M.G. (1997b). Molecular mechanisms of G protein-coupled receptor signaling: role of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins in receptor desensitization and resensitization. Receptors Channels 5, 193-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]