Abstract

Vascular cognitive impairment is an umbrella term for cognitive dysfunction associated with and presumed to be caused by vascular brain damage. Autopsy studies have identified microinfarcts as an important neuropathological correlate of vascular cognitive impairment that escapes detection by conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As a frame of reference for future high-resolution MRI studies, we systematically reviewed the literature on neuropathological studies on cerebral microinfarcts in the context of vascular disease, vascular risk factors, cognitive decline and dementia. We identified 32 original patient studies involving 10,515 people. The overall picture is that microinfarcts are common, particularly in patients with vascular dementia (weighted average 62%), Alzheimer's disease (43%), and demented patients with both Alzheimer-type and cerebrovascular pathology (33%) compared with nondemented older individuals (24%). In many patients, multiple microinfarcts were detected. Microinfarcts are described as minute foci with neuronal loss, gliosis, pallor, or more cystic lesions. They are found in all brain regions, possibly more so in the cerebral cortex, particularly in watershed areas. Reported sizes vary from 50 μm to a few mm, which is within the detection limit of current high-resolution MRI. Detection of these lesions in vivo would have a high potential for future pathophysiological studies in vascular cognitive impairment.

Keywords: cerebral microinfarct, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, MRI, neuropathology

Introduction

Cerebrovascular disease is a common cause of cognitive decline and dementia. Cognitive decline associated with and presumed to be caused by cerebrovascular disease is referred to as vascular cognitive impairment (O'Brien et al, 2003). Vascular cognitive impairment is thus an umbrella term for various clinical syndromes (e.g., vascular dementia (VaD), poststroke dementia) and dementia associated with vascular risk factors. It comprises heterogenic pathological processes that affect both the brain vessels and parenchyma. Damage to brain parenchyma is visible on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as lacunar and nonlacunar infarcts, macrohemorrhages and microhemorrhages and white matter hyperintensities (Pantoni, 2010).

Recent brain autopsy studies showed that microinfarcts are another type of vascular brain damage that is related to impaired cognition, also in patients with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) without apparent macroscopic vascular pathology (White et al, 2002; Kalaria et al, 2004; Kövari et al, 2007). Because of their limited size, microinfarcts go undetected on conventional MRI. However, with the introduction of ultra-high field strength clinical MR scanners, which offer a higher spatial resolution, it may be possible to detect them in vivo. In light of these new developments, it is important to collect the data that are already available on microinfarcts from neuropathological studies, to form a frame of reference for future MRI studies. The aim of this paper was to systematically review the literature on neuropathological studies on microinfarcts as a marker of brain injury related to vascular diseases, vascular risk factors, and cognitive impairment.

Materials and methods

Literature Search Strategy

Studies were identified by a systematic search of MEDLINE and EMBASE (1966 to 11 July 2011). In brief, we used the search term ‘microinfarct' and synonyms, for example, microinfarction, microischemia, microvascular infarct, and microvascular ischemia (for search string see Supplementary Table 1). Because we expected a limited number of relevant studies, we used a broad array of search terms in full and truncated form to identify all available papers. The bibliographies of relevant original and review articles were screened. Relevant studies were then selected by screening of title and abstract against predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were (1) original patient studies (no reviews) concerning cerebral microinfarcts, either in the general population or related to vascular brain damage (e.g., stroke, small vessel disease), vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus), or cognitive impairment or dementia; (2) the characteristics, frequency, or distribution of microinfarcts had to be described in the study. No restriction on design or pathological assessment method was made. Case reports, narrative reviews, letters, animal studies, and articles in languages other than English were excluded. Moreover, studies regarding autoimmune brain diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis) or acute encephalopathy (e.g., hypertensive or postanoxic encephalopathy) were excluded. Studies that did not distinguish between microinfarcts and lacunar infarcts (i.e., studies that combined all small infarcts <1.5 cm in their reports) were also excluded.

Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from included papers: (1) Study design: pro/retrospective cohort, population-based or hospital-based; (2) Diagnosis of the examined group and sample size per diagnosis; (3) Diagnostic procedure: primarily on clinical criteria, primarily on neuropathological criteria, or on both; (4) Demographics: mean age at death and gender; and (5) Pathological assessment method: sampling sites and slice thickness (see Supplementary Table 2), staining methods, and immunohistochemistry. To facilitate interpretation of data presented in tables, data are grouped according to the following diagnoses: reference groups, AD, VaD, cerebrovascular disease, and mixed dementia groups. Within these groups, the frequency, size, characteristics, and distribution of microinfarcts and the number of microinfarcts per patient were listed (Table 2).

Results

The literature search of MEDLINE and EMBASE yielded 571 articles. Of these, 516 articles were excluded for the following reasons: reports on microinfarcts in other organs than the brain (n=276), reports on conditions other than chronic cerebrovascular disease, for example, acute encephalopathy, infection, or epilepsy (n=119), animal studies (n=45), narrative reviews (n=33), case reports (n=27), letters/comments (n=5), or language other than English (n=11). Eight more articles were included after screening the reference lists of the included articles. The majority of these were not identified by the original search because cerebral vascular injury was described in more general terms in title and abstract.

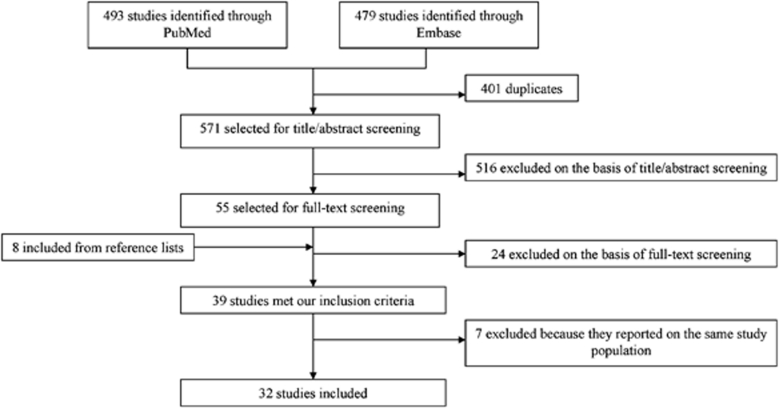

Thirty-nine articles met the inclusion criteria. One paper concerned three different cohorts (Longstreth et al, 2009), from which we only used the data of the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center. For the other two cohorts in that paper (i.e., the ACT (Adult Changes in Thought) Study and the HAAS (Honolulu Asia Aging Study)), data were extracted from the original published articles (White et al, 2002; White, 2009; Wang et al, 2009). When more than one paper reported on the same population (Sonnen et al, 2007, 2009a, 2010; Wang et al, 2009; Gold et al, 1997, 2002, 2005, 2007; Kövari et al, 2004, 2007; Santos et al, 2010; Sinka et al, 2010), the paper with the largest population sample and the most detailed information on microinfarcts was included. There were two exceptions. Two out of four papers concerning the ACT cohort (Sonnen et al, 2007, 2009a, 2010; Wang et al, 2009) were included, because they described different samples from this cohort (Wang et al, 2009; Sonnen et al, 2007). Three out of eight papers concerning a cohort of autopsied patients at the Geriatric and Psychiatric Hospitals of the University of Geneva were included (Kövari et al, 2004, 2007; Gold et al, 2002, 1997, 2005, 2007; Santos et al, 2010; Sinka et al, 2010). The paper by Gold et al (2007) described the largest sample. Two additional papers (Kövari et al, 2007; Sinka et al, 2010) were also included because they provided relevant detailed information on subsamples of this cohort (AD Braak stage III and dementia, respectively). Hence, a total of 32 articles were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of included studies.

The design of these studies and the population characteristics are summarized in Table 1; data on the frequency, size, and characteristics of microinfarcts are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Designa | Diagnosis (sample size)b | Diagnosis based onc | Mean age at death (years) (range) | Male (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arvanitakis et al (2011) | P | Population-based | 1. Dementia (192) | Clinical (NINCDS-ADRDA) | 1. 89 | 1. 35 |

| 2. No dementia (233) | 2. 85 | 2. 43 | ||||

| Ballard et al (2000) | R | Population-based | 1. VaD (19) 2. NDD+VaD (11) 3. AD (37) | Clinical (DSM), neuropathology (NINDS-AIREN) | 77 (Onset dementia) | 57 |

| Brayne et al (2009) | RP | Population-based | 1. Dementia (113) 2. No dementia (100) | Clinical (DSM) | 91 (81–101) | 30 |

| De Reuck et al (2011a) | RP | Hospital-based | 1. AD (45) 2. DLB (8) 3. FTD (12) 4. No dementia (10) | Neuropathology (Braak) | 1. 81 2. 78 3. 69 4. 69 | 1. 51 2. 63 3. 50 4. 60 |

| De Reuck et al (2011b) | RP | Hospital-based | 1. AD—CAA (12) 2. AD—no CAA (28) | Neuropathology (Braak) | 1. 79 2. 76 | 1. 50 2. 43 |

| Erkinjuntti et al (1988) | RP | Hospital-based | 1. AD (5) 2. VaD (27) 3. Dementia due to other causes (5) | Clinical (DSM) | 1. 74 (57–83) 2. 80 (61–92) 3. 79 (74–83) | 1. 60 2. 37 3. 40 |

| Esiri et al (1997) | RP | Hospital-based | 1.CVD (19) 2. VaD (24) 3. No dementia (18) | Neuropathology | 1. 83 2. 76 3. 80 | 1. 63 2. 38 3. 55 |

| Ghebremedhin et al (2010) | R | Hospital-based | 1. DLB (13) 2. PD (102) 3. No dementia, no PD (53) | Clinical | 1. 76 2. 75 3. 74 | 1. 38 2. 59 3. 58 |

| Gold et al (2007) | RP | Hospital-based | Dementia and no dementia (156) | Clinical (CDR) | 87 (73–101) | 41 |

| Haglund et al (2006) | RP | Hospital-based | VaD without AD (26) | Neuropathology | 82 | 50 |

| Isojima et al (2006) | R | X | 1. DLB (25) 2. AD (63) | Neuropathology (AD: CERAD) | 1. 81 (67–94) 2. 83 (67–94) | 1. 48 2. 35 |

| Kövari et al (2007) | RP | Hospital-based | AD Braak stage 3 (43) | Neuropathology (Braak) | (73–101) | 28 |

| Lee et al (2000) | P | Hospital-based | 1. AD+CVD (201) 2. AD (36) | Neuropathology (NIA), clinical (DSM) | 1. 79 2. 84 | 1. 30 2. 48 |

| Longstreth et al (2009) | R | Hospital-based | Admitted to NACC (6189) | Neuropathology | 81 | 48 |

| Okamoto et al (2009) | R | Hospital-based | 1. AD (8) 2. VaD (6) | Neuropathology (CERAD, Braak) | 1. 79 2. 77 | X |

| Olichney et al (1997) | R | Hospital-based | 1. AD—severe CAA (50) 2. AD—mild CAA (198) | Neuropathology (CERAD) | X | 1. 66 2. 55 |

| Rossi et al (2004) | RP | Hospital- and population-based | 1. AD (49) 2. Non-AD dementia (17) 3. MCI (3) 4. No dementia (18) | Neuropathology | 73 (44–99) | 48 |

| Santos et al (2009) | R | Hospital-based | 1. Poststroke depression (20) 2. No poststroke depression (21) | Neuropathology (stroke), DSM (poststroke depression) | 1. 77 (Stroke) 2. 78 (Stroke) | 1. 45 2. 52 |

| Schneider et al (2007b) | RP | Population-based | No dementia (148) | Clinical | 88 | 43 |

| Del Ser et al (2005) | RP | Hospital-based | 1. AD (35) 2. AD+CVD (22) | Neuropathology | 1. 77 2. 83 | 1. 46 2. 14 |

| Sinka et al (2010) | RP | Hospital-based | 1. Dementia (71) 2. No dementia (22) | Clinical (DSM) | 1. 95 2. 95 | 1. 36 2. 32 |

| Sonnen et al (2007) | RP | Population-based | 1. Dementia (75) 2. MCI (47) 3.No dementia (89) | Clinical (CASI, DSM) | 1. 89 2. 88 3. 84 | 1. 44 2. 49 3. 37 |

| Soontornniyomkij et al (2010) | R | Hospital-based | 1. Dementia+severe CAA (18) 2. Dementia+mild CAA (21) | Clinical (dementia), neuropathology (CAA) | 1. 82 (62–97) 2. 84 (69–101) | 1. 56 2. 52 |

| Strozyk et al (2010) | RP | Hospital- and population-based | 1. Dementia (131) 2. No dementia (59) | Clinical (DSM) | 84 | 35 |

| Suter et al (2002) | R | X | 1. AD (105) 2. No dementia (79) | Neuropathology (NIA, CERAD) | 1. 78 (54–98) 2. 72 (57–87) | X |

| Troncoso et al (2008) | RP | Population-based | Elderly±dementia (179) | Clinical (DSM) | 87 | 68 |

| Vinters et al (2000) | RP | Hospital-based | 1. ±Dementia/CVD (20) 2. No dementia, no CVD (3) | Clinical, MRI | 1. 80 (68–92) 2. 80 (74–87) | 1. 65 2. 67 |

| Wang et al (2009) | RP | Population-based | 1. Age 65–80 years (148) 2. Age >80 years (102) | Age | 1. 82 2.92 | 1. 45 2. 39 |

| White et al (2002) | P | Population-based (selected) | Elderly (285) | Age | 85 (74–97) | 100 |

| White (2009) | RP | Population-based | 1. Dementia (183) 2. MCI (I70) 3. No dementia (190) | Clinical (CASI) | X | 100 |

| Xuereb et al (2000) | P | Population-based | 1. Dementia (47) 2. No dementia (52) | Clinical (CAMDEX) | X (>75) | 1. 35 2. 30 |

| Yip et al (2005) | R | Hospital-based | AD (99) | Neuropathology (NIA) | 75 | 96 |

Studies are listed in alphabetical order. X denotes unknown/not-specified.

Design: P, prospective; R, retrospective; RP, retrospective from prospective cohort.

Diagnosis: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MD, mixed dementia; NDD, neurodegenerative disease; PD, Parkinson's disease; VaD, vascular dementia.

Diagnosis based on: CAMDEX, Cambridge Diagnostic Examination for the Elderly; CASI, Cognitive Assessment Screening Instrument; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating scale; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; NIA, National Institute on Aging-Reagan Institute; NINCDS-ADRDA, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke—Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria for Alzheimer's Disease; NINDS-AIREN, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l′Enseignement en Neurosciences criteria for vascular dementia.

Table 2. Microinfarcts in specific diagnostic groups.

| Study | Sample (size) | Frequency (%) | Size | Characteristicsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference groups | ||||

| Arvanitakis et al (2011 | Controls (233) | 25.3 | Microscopic | X |

| Brayne et al (2009) | Controls (100) | 43 | X | X |

| De Reuck et al (2011a) | Controls (10) | 10 | X | X |

| Ghebremedhin et al (2010) | Controls (53) | 5.7 | <2 mm | X |

| Schneider et al (2007b) | Controls (148) | 24 | Microscopic | Acute: 4; chronic: 1, 2 |

| Sinka et al (2010) | Controls (22) | 18.2 | <1 mm | X |

| Sonnen et al (2007) | Controls (89) | 29 | Microscopic | 1, 3, 5 |

| Suter et al (2002) | Controls (79) | 2.5 | 300 μm to 2 mm | X |

| Vinters et al (2000) | Controls (3) | 33 | Microscopic | 1, 4 |

| Wang et al (2009) | 1. Age 65–80 years (148) | 1. 20.4 | Microscopic | X |

| 2. Age >80 years (102) | 2. 24.2 | |||

| White (2009) | Controls (190) | X | Microscopic | 1, 3, 5 |

| Xuereb et al (2000) | Controls (52) | 33.3 | X | X |

| Total: 1,229 | Weighted average: 24 | |||

| MCI | ||||

| Sonnen et al (2007) | MCI (47) | 56 | Microscopic | 1, 3, 5 |

| White (2009) | MCI (I70) | X | Microscopic | 1, 3, 5 |

| Total: 217 | ||||

| AD | ||||

| Brayne et al (2009) | AD (76) | 44 | X | X |

| De Reuck et al (2011a) | AD (45) | 15.6 | X | X |

| Erkinjuntti et al (1988) | AD (5) | 20 | Microscopic | 1, 3, 4 |

| Isojima et al (2006) | AD (63) | 68 | Microscopic | X |

| Kövari et al (2007) | AD (43) | 27.9 | Microscopic | X |

| Okamoto et al (2009) | AD (8) | 100 | 100–500 μm | 1, 4 |

| Suter et al (2002) | AD (105) | 32.4 | 300 μm to 2 mm | X |

| Yip et al (2005) | AD (99) | X (rare) | <2 mm | 1, 2 |

| Total: 409 | Weighted average: 43 | |||

| VaD | ||||

| Brayne et al (2009) | VaD (4) | 100 | X | X |

| Erkinjuntti et al (1988) | VaD (27) | 70.4 | Microscopic | 1, 3, 4 |

| Esiri et al (1997) | VaD (24) | 63 | Microscopic | GM: 1, 2, 5; WM: 2 |

| Haglund et al (2006) | VaD (26) | 57.7 | <5 mm | 3, 4 |

| Okamoto et al (2009) | VaD (6) | 16.7 | 100–500 μm | 1, 4 |

| Total: 87 | Weighted average: 62 | |||

| Mixed dementia | ||||

| Ballard et al (2000) | VaD±NDD (67) | 40 | X | GM: 1, 2, 5; WM: 2 |

| Brayne et al (2009) | AD+VaD (25) | 75 | X | X |

| Lee et al (2000) | AD+CVD (201) | 50 | X | 5 |

| Olichney et al (1997) | 1. AD—severe CAA (50) | 1. 22 | X | X |

| 2. AD—mild CAA (198) | 2. 9 | |||

| De Reuck et al (2011b) | AD—CAA (12) | 42 | X | X |

| Del Ser et al (2005) | AD (35), AD+CVD (22) | X | <0.5 mm | 1, 2 |

| Total: 553 | Weighted average: 33 | |||

AD, Alzheimer's disease; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; GM, gray matter; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NDD, neurodegenerative disease; VaD, vascular dementia; WM, white matter; X, unknown.

Grouped as following: (1) gliotic lesions, including noncystic lesions, microglial nodules, astrocytosis and fibrous and gemistocytic astrocytes; (2) cystic lesions (some described with ragged edges); (3) necrotic lesions and pallor, including focal leukoencephalopathy, foci of myelin loss and tissue devitalization; (4) inflammatory reaction, including histiocytosis, activated macrophages, and microglial activation; and (5) neuronal loss or granular cortical atrophy.

Table 3. Microinfarcts in other diagnostic groups.

| Study | Sample (size) | Frequency (%) | Size | Characteristicsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia/no dementia combined | ||||

| Gold et al (2007) | Dementia/no dementia (156) | 41.7 | <1 mm | X |

| Longstreth et al (2009) | Age>65 years (±dementia) (6,189) | 19.7 | Microscopic | X (Macroscopically 5) |

| Rossi et al (2004) | AD, dementia, MCI, controls (87) | 40 | X | GM: 1, 2, 5; WM: 2 |

| Strozyk et al (2010) | Dementia (131), controls (59) | 15.8 | Microscopic | 1, 2, 3 |

| Troncoso et al (2008) | Dementia/no dementia (179) | 21.8 | Microscopic | X |

| White et al (2002) | Elderly (285) | 19.3 (80.7 Negligible) | 50–400 μm, Cystic larger | 1, 3, 5 |

| Dementia not specified | ||||

| Arvanitakis et al (2011) | Dementia (192) | 36.5 | Microscopic | X |

| Sonnen et al (2007) | Dementia (75) | 63 | Microscopic | 1, 3, 5 |

| Xuereb et al (2000) | Dementia (47) | 40.5 | X | X |

| White (2009) | Dementia (183) | X | Microscopic | 1, 3, 5 |

| Sinka et al (2010) | Dementia (71) | 54.9 | <1 mm | X |

| DLB | ||||

| Isojima et al (2006) | DLB (25) | 40 | Microscopic | X |

| De Reuck et al (2011b) | DLB (8) | 17.5 | X | X |

| Ghebremedhin et al (2010) | DLB (13) | 30.8 | <2 mm | X |

| Vascular brain damage | ||||

| Esiri et al (1997) | CVD (19) | 26 | Microscopic | GM: 1, 2, 5; WM: 2 |

| Santos et al (2009) | 1. Poststroke depression (20) | 1. LH 35, RH 55 | Microscopic | 3, 5 |

| 2. No poststroke depression (21) | 2. LH 24, RH 52 | |||

| Soontornniyomkij et al (2010) | 1. Dementia+severe CAA (18) | 1. 77.8 | <5 mm | 4 |

| 2. Dementia+mild CAA (21) | 2. 33.3 | |||

| Vinters et al (2000) | ±Dementia/subcortical CVD (20) | 60 | Microscopic | 1, 4 |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; GM, gray matter; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; WM, white matter; X, unknown.

Grouped as following: (1) gliotic lesions, including noncystic lesions, microglial nodules, astrocytosis and fibrous and gemistocytic astrocytes; (2) cystic lesions (some described with ragged edges); (3) necrotic lesions and pallor, including focal leukoencephalopathy, foci of myelin loss and tissue devitalization; (4) inflammatory reaction, including histiocytosis, activated macrophages, and microglial activation; and (5) neuronal loss or granular cortical atrophy.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

Most studies had a retrospective design (some of a prospectively selected cohort); only four studies were prospective (Lee et al, 2000; White et al, 2002; White, 2009; Arvanitakis et al, 2011). The greater part (63%) concerned hospital-based cohorts, mostly patients admitted to geriatric hospitals or dementia clinics. Twelve studies (41%) described a population-based cohort (Arvanitakis et al, 2011; Ballard et al, 2000; Rossi et al, 2004; Brayne et al, 2009; Xuereb et al, 2000; White et al, 2002; Sonnen et al, 2007; Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Strozyk et al, 2010; Troncoso et al, 2008; White, 2009; Wang et al, 2009), mostly of elderly, that is, the ACT Study (Sonnen et al, 2007; Wang et al, 2009) or the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (Troncoso et al, 2008). Two of these population-based studies involved specific groups of individuals: that is, only men (HAAS) (White et al, 2002; White, 2009) or people from religious orders (Religious Orders Study (Arvanitakis et al, 2011)) (Table 1).

The majority of patient studies concerned patients with dementia (AD (n=8), VaD (n=5), Lewy Body Dementia (n=3), or different types of dementia mixed (n=5)), with or without a nondemented reference group. Six studies reported on a combination of people with and without dementia described as a single group. Two studies assessed patients with stroke (Esiri et al, 1997; Santos et al, 2009), one study elderly without describing their cognitive status (Longstreth et al, 2009). Three papers concerned patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) (Olichney et al, 1997; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010; De Reuck et al, 2011a).

Thirteen studies (41%) diagnosed the patients primarily on neuropathological criteria (Esiri et al, 1997; Olichney et al, 1997; Suter et al, 2002; Rossi et al, 2004; Del Ser et al, 2005; Yip et al, 2005; Haglund et al, 2006; Isojima et al, 2006; Kövari et al, 2007; Longstreth et al, 2009; Okamoto et al, 2009; De Reuck et al, 2011a, 2011b). The most commonly used neuropathological criteria for AD were the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) (Mirra et al, 1991) and the Braak criteria (Braak and Braak, 1991). Fifteen studies (41%) primarily classified the patients on clinical criteria (Erkinjuntti et al, 1988; Vinters et al, 2000; Xuereb et al, 2000; White et al, 2002; Gold et al, 2007; Sonnen et al, 2007; Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Strozyk et al, 2010; Troncoso et al, 2008; White, 2009; Wang et al, 2009; Brayne et al, 2009; Ghebremedhin et al, 2010; Sinka et al, 2010; Arvanitakis et al, 2011). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) was used most frequently, followed by the Cognitive Assessment Screening Instrument (Teng et al, 1994). Four studies based their diagnosis on a combination of neuropathology (cerebrovascular disease, AD, stroke, CAA) and clinical examination (dementia, depression) (Lee et al, 2000; Ballard et al, 2000; Santos et al, 2009; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010) (Table 1).

The number of included patients varied per study between 14 and 6,189, with a mean of 332 and a median of 99 patients. Different definitions of age were used. Age at death was most often used, which varied between a mean of 69 and 95 years of age. One paper reported age at onset of dementia (Ballard et al, 2000), another the age at which stroke occurred (Santos et al, 2009) (Table 1).

Pathological Assessment Method

The areas of the brain that were sampled varied across papers. Eleven studies (34%) investigated only one hemisphere (Erkinjuntti et al, 1988; Xuereb et al, 2000; Lee et al, 2000; Rossi et al, 2004; Isojima et al, 2006; Strozyk et al, 2010; Troncoso et al, 2008; Brayne et al, 2009; Arvanitakis et al, 2011; De Reuck et al, 2011a, 2011b), while 13 studies (41%) assessed both hemispheres (Ballard et al, 2000; Esiri et al, 1997; White et al, 2002; Del Ser et al, 2005; Haglund et al, 2006; Gold et al, 2007; Kövari et al, 2007; Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Wang et al, 2009; Santos et al, 2009; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010; Sinka et al, 2010; White, 2009). The remainder (25%) did not specify which hemispheres were investigated (Olichney et al, 1997; Vinters et al, 2000; Suter et al, 2002; Yip et al, 2005; Sonnen et al, 2007; Longstreth et al, 2009; Okamoto et al, 2009; Ghebremedhin et al, 2010).

Twenty papers (69%) specified a sampling protocol that covered the major parts of the brain, including the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes, deep white and gray matter, brainstem, and sometimes also the cerebellum (Erkinjuntti et al, 1988; Esiri et al, 1997; Lee et al, 2000; Ballard et al, 2000; Isojima et al, 2006; Brayne et al, 2009; Ghebremedhin et al, 2010; Rossi et al, 2004; Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Vinters et al, 2000; Xuereb et al, 2000; White et al, 2002; Yip et al, 2005; Del Ser et al, 2005; Sonnen et al, 2007; Strozyk et al, 2010; Troncoso et al, 2008; White, 2009; Wang et al, 2009; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010). The remaining studies had a more limited brain coverage, that is, only the four lobes (Okamoto et al, 2009) or the temporal, parietal and frontal lobes combined with deep gray matter (Olichney et al, 1997; Gold et al, 2007; Kövari et al, 2007; Santos et al, 2009). One study focused on the watershed areas (Suter et al, 2002), another study only on one midtemporal, and one midparietal section (Haglund et al, 2006) (see Supplementary Table 2).

A brain slice thickness for macroscopic examination of 10 mm was most common (14 studies, 44%). One study used a brain slice thickness of 5 mm (Vinters et al, 2000). The brain slice thickness was not specified in 17 papers (53%). The thickness of microscopic slices was 6 μm in three studies, 7 or 8 μm in one study each, 10 and 20 μm in four studies each, and it was not specified in 19 studies (59%) (see Supplementary Table 2).

Three studies reported to have used immunohistochemistry to visualize astrocytes, microglia, and macrophages, that is, with primary antibodies to glial fibrillary acidic protein (Vinters et al, 2000; Okamoto et al, 2009) or to Cluster of Differentiation 68 (CD-68) (Okamoto et al, 2009; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010).

Histological Characteristics of Microinfarcts

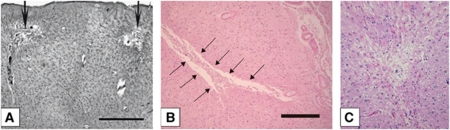

The description of the appearance of microinfarcts varied between the studies from slit-like, triangular, round, barrel-shaped, stellate, granular to wedge-shaped forms. Frequently used terms were foci with neuronal loss (five studies), gliosis (10 studies), cystic lesions (eight studies), or foci with pallor (two studies) (Tables 2 and 3; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of different types of cerebral microinfarcts. Photomicrographs showing cortical cystic microinfarcts (A, B) and a small focus of collapsed gliotic tissue (C). Material was stained with Globus silver staining (A) and hematoxylin and eosin staining (B, C). Scale bar: (A) 1,000 mm; (B) 250 mm. (Images from Gold et al, 2007 (A); Okamoto et al, 2009 (B); Strozyk et al, 2010 (C).)

Six studies described features of an inflammatory response, namely activated macrophages (Erkinjuntti et al, 1988; Haglund et al, 2006; Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Okamoto et al, 2009; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010), microglial activation (Haglund et al, 2006), and histiocytosis (Vinters et al, 2000). Two papers reported to have used immunohistochemistry to define this inflammatory response. Okamoto et al (2009) used infiltration by both glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive astrocytes and CD-68-positive microglia/microphages as a marker of recent occurrence of microinfarcts. In contrast, Soontornniyomkij et al (2010) considered microscopic foci of CD-68-positive macrophage-infiltrated tissue destruction to be old microinfarcts. A few studies only included temporally remote microinfarcts, which they described as cystic or gliotic lesions and foci of pallor (White et al, 2002; Sonnen et al, 2007; White, 2009).

Four papers only focused on cortical microinfarcts, which some of them described as widespread multiple tiny infarcts (Lee et al, 2000; Longstreth et al, 2009; Santos et al, 2009; Sinka et al, 2010).

A substantial number of studies (50%) did not specify the term ‘microinfarct,' other than naming them ‘ischemic lesions.'

Overall, it seems to be that there is no universally accepted histological definition of microinfarcts in neuropathological studies, but that lesions can vary in shape and can appear both cystic or as more gliotic, pale lesions. In the acute stage there can be an inflammatory response.

Size of Microinfarcts

Fourteen papers (44%) defined the size of microinfarcts as ‘not visible with the naked eye' or ‘only visible upon light microscopy' (Erkinjuntti et al, 1988; Arvanitakis et al, 2011; Esiri et al, 1997; Vinters et al, 2000; Isojima et al, 2006; Kövari et al, 2007; Sonnen et al, 2007; Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Strozyk et al, 2010; Troncoso et al, 2008; Longstreth et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2009; Santos et al, 2009; White et al, 2002). Some studies (31%) explicitly described sizes of microinfarcts: 50 to 400 μm (with cystic microinfarcts being somewhat larger than noncystic microinfarcts) (White et al, 2002); 100 to 500 μm (Okamoto et al, 2009); 300 μm to 2 mm (Suter et al, 2002); ≤0.5 mm (Del Ser et al, 2005); <1 mm (Gold et al, 2007; Sinka et al, 2010); ≤2 mm (Yip et al, 2005; Ghebremedhin et al, 2010); ≤5 mm (Haglund et al, 2006; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010). The remaining studies (25%) did not define the size of the lesions that they considered microinfarcts (Olichney et al, 1997; Xuereb et al, 2000; Lee et al, 2000; Ballard et al, 2000; Rossi et al, 2004; Brayne et al, 2009; De Reuck et al, 2011a, 2011b) (Tables 2 and 3).

Distribution of Microinfarcts

The compiled data of the included studies indicate that microinfarcts can occur throughout the brain, in both cortical and subcortical gray matter and white matter.

Several papers (34%) allowed comparison of lesion occurrence between the cortex and subcortical areas. Some of these studies showed microinfarcts in all cortical and subcortical regions, which were assessed (Ballard et al, 2000; White et al, 2002), or described them more globally in gray and white matter (Vinters et al, 2000; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010; Troncoso et al, 2008; Wang et al, 2009). Only two studies specifically mentioned that there was no difference in appearance of microinfarcts between the cortex and subcortical regions (Ballard et al, 2000; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010), while one study described them to be more common in the subcortical areas (Arvanitakis et al, 2011). However, most of these studies did not describe if microinfarcts preferentially occurred in cortical or subcortical regions. Regarding specific brain areas, two studies described them to appear most commonly in the parietal and occipital regions (Okamoto et al, 2009; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010). Two studies found microinfarcts only in the watershed areas (Suter et al, 2002; Strozyk et al, 2010), others only in the cortical gray matter (Olichney et al, 1997; Lee et al, 2000). White et al (2002) found cortical microinfarcts mostly located toward the base of the gray matter, while Okamoto et al (2009) described them mostly in the superficial layers of the cortex.

Taken together, these results indicate that microinfarcts can appear in all brain areas. Most studies did not specifically compare lesion occurrence in different brain regions. Some found them to be more abundant in the watershed areas or cerebral cortex.

Frequency

Frequencies of cerebral microinfarcts are described in Tables 2 and 3. Twelve studies included nondemented people, totaling 1,229 individuals (Vinters et al, 2000; Xuereb et al, 2000; Suter et al, 2002; Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Sonnen et al, 2007; Brayne et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2009; White, 2009; Ghebremedhin et al, 2010; Sinka et al, 2010; Arvanitakis et al, 2011; De Reuck et al, 2011a). The frequency of microinfarcts ranged from 3% to 43% (weighted average 24%).

Eight studies concerned patients with AD (Erkinjuntti et al, 1988; Suter et al, 2002; Yip et al, 2005; Isojima et al, 2006; Kövari et al, 2007; Brayne et al, 2009; Okamoto et al, 2009; De Reuck et al, 2011b), with a total sample size of 409 patients (range 5 to 105). Microinfarcts were detected in 20% to 100% of the patients, with a weighted average of 43%. One study on patients with AD only described microinfarcts to be ‘rare' (Yip et al, 2005).

In five studies on VaD, with a total sample size of 87 (range 4 to 27), the frequency of microinfarcts ranged from 16.7% to 100%, with a weighted average of 62% (Erkinjuntti et al, 1988; Esiri et al, 1997; Haglund et al, 2006; Brayne et al, 2009; Okamoto et al, 2009).

Six articles investigated pooled populations of patients with AD and VaD or cerebrovascular disease. In five of these papers, the frequency could be extracted. The summed sample size was 553, and the weighted frequency was 33% (Olichney et al, 1997; Lee et al, 2000; Ballard et al, 2000; Del Ser et al, 2005; Brayne et al, 2009; De Reuck et al, 2011a).

One study reported that microinfarcts were detected in 27 (56%) of 47 patients with mild cognitive impairment (Sonnen et al, 2007). The frequency of microinfarcts was relatively high in patients with mild cognitive impairment compared with the other diagnostic groups, but this estimate was only based on a small number of patients.

Three studies examined patient groups with vascular brain disease. Esiri et al (1997) identified microinfarcts in 26% of the cases with neuropathological determined cerebrovascular disease, Soontornniyomkij et al (2010) in 78% of the demented patients with severe and in 33% of the patients with mild or absent amyloid angiopathy. Finally, Santos et al (2009) identified similar prevalences in patients with and without poststroke depression (left hemisphere 35% to 24% and right hemisphere 55% to 52%).

The frequency in mixed populations of patients with and without dementia ranged from 16% to 42% (weighted average 20%) (White et al, 2002; Rossi et al, 2004; Gold et al, 2007; Strozyk et al, 2010; Troncoso et al, 2008; Longstreth et al, 2009).

One study observed that the mean age was significantly higher in those with microinfarcts (Longstreth et al, 2009). Overall, the mean age at death of the different study populations was quite homogeneous. Therefore, based on our survey, no definite conclusions can be drawn on the relation between age and microinfarct occurrence. The extensiveness of pathological assessment (i.e., the amount of examined brain regions and slice thickness) seemed to have no influence on the frequency, though it was difficult to compare the studies and frequencies because of the variety of assessment methods and study populations.

Overall, the frequency of microinfarcts varied across studies, but microinfarcts are particularly common in patients with other types of cerebrovascular brain damage and/or dementia.

Number of Microinfarcts per Patient

The majority of studies (72%) did not specify lesion numbers per individual patient. Haglund et al (2006) mentioned a maximum of 15 microinfarcts detected in one patient (only one midtemporal and one midparietal coronal section were examined). Arvanitakis et al (2011) reported a mean number of microinfarcts of 1.6±0.9, 62% of the 129 persons had a single microinfarct, and 38% had multiple microinfarcts.

Some studies used a semiquantitative scale, for example 0, 1 to 2, and >2 microinfarcts (with corresponding prevalence that ranged from 6% with multiple microinfarcts in nondemented individuals to 31% in patients with dementia) (Sonnen et al, 2007); <3; 3; ≥4 in the basal ganglia and thalamus and <3; 3 to 4; ≥5 in the neocortex (81% of the patients had <3 microinfarcts in both categories, 1% the highest category) (White et al, 2002); or ‘multiple' (Vinters et al, 2000; Lee et al, 2000). The remaining studies mentioned the number of microinfarcts per patient more precisely: 0 to 4 in patients with different types of dementia (Erkinjuntti et al, 1988); a mean of six microinfarcts (range 1 to 37) in 14 patients with severe CAA and 3 (range 1 to 6) in 7 patients with mild CAA (Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010); 1 to 4 per watershed zone area (Suter et al, 2002).

In summary, in studies that mentioned the number of microinfarcts per patient, the majority of patients had multiple infarcts. Importantly, it should be noted that it is impossible to examine the whole brain neuropathologically and quite a number of studies investigated only limited sampling sites. Therefore, the actual number of microinfarcts per individual could be up to several hundred fold higher than has been described in these studies.

Clinical Correlates of Microinfarcts

Because papers examined different study populations, microinfarcts were reported to be associated with various conditions. Several studies reported microinfarcts to be associated with a clinical diagnosis of ‘dementia' (Gold et al, 2007; Sonnen et al, 2007; Troncoso et al, 2008; Sinka et al, 2010; Arvanitakis et al, 2011), neuropathologically confirmed AD (Suter et al, 2002; Isojima et al, 2006; Okamoto et al, 2009), a clinical diagnosis of VaD (Esiri et al, 1997; Brayne et al, 2009), or ‘cognitive dysfunction' (White et al, 2002; Kövari et al, 2007; White, 2009). However, others found no relationship between microinfarcts and dementia (Strozyk et al, 2010; Brayne et al, 2009), AD pathology (Xuereb et al, 2000), or pathologically determined VaD (Okamoto et al, 2009). There were no differences in sample size or pathological assessment method between papers that have or have not found an association with different forms of dementia. Overall, the group of investigated patients with VaD was small. The occurrence of cavitated microinfarcts in the basal ganglia in patients with AD may be modulated by APOE4 genotype (Yip et al, 2005).

A number of studies found an association between microinfarcts and other cerebrovascular disease: lacunar infarcts (Vinters et al, 2000; Rossi et al, 2004), small (<15 mL) macroscopic infarcts (Ballard et al, 2000), macroinfarcts (Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Troncoso et al, 2008; Longstreth et al, 2009; Arvanitakis et al, 2011), and leukoencephalopathy (Rossi et al, 2004; Longstreth et al, 2009). There may be an association between microinfarcts and CAA, but reported frequencies are not consistent (Olichney et al, 1997; Haglund et al, 2006; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010; De Reuck et al, 2011a).

Finally, a few studies described a relationship between microinfarcts and vascular risk factors (systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, myocardial ischemia) (Wang et al, 2009; Longstreth et al, 2009; Sonnen et al, 2009b).

Discussion

This systematic review includes 32 papers concerning neuropathological studies on cerebral microinfarcts in patients with cognitive dysfunction or cerebrovascular disease. Microinfarcts are described as gliotic or cystic lesions, sometimes with neuronal loss, and may occur in all brain regions, although the cerebral cortex may be a preferential location. Microinfarcts are commonly described in the elderly, particularly in patients with VaD, AD, and cerebrovascular disease. In the majority of cases, multiple microinfarcts are observed.

The studies described in this review differed in several aspects. Study populations did not only consist of groups of patients with different types of dementia, but also involved demented and nondemented people together and groups with different types of cerebrovascular disease. The frequency of microinfarcts seems to increase in patients with dementia (VaD as well as AD) and dementia combined with cerebrovascular disease compared with controls. However, because pathology studies cannot achieve full brain coverage, these numbers are unlikely to be precise estimates of the true prevalence of microinfarcts. For the same reason, it is difficult to draw conclusions on the number of microinfarcts per patient. In the papers that did report microinfarct numbers in their samples, the majority of patients had multiple microinfarcts. Therefore, the actual number for the whole brain could be up to hundreds or thousands. About half of the studies used a population-based cohort, the others a hospital-based cohort. In both types of cohorts, sampling bias is inevitable. A limitation of population-based studies is selection bias, due to a limited number of participants. In hospital-based studies, especially from tertiary reference centers, atypical types of dementia could be overrepresented. However, we have not found systematic differences in frequency of microinfarcts between these two types of cohorts.

Finally, we used a broad array of search terms to find as many neuropathological studies on cerebral microinfarcts as possible, and did not use inclusion/exclusion criteria with respect to specific features or definitions of the microinfarcts. This is reflected in the large variability in the characteristics of microinfarcts reported in the different studies, such as size and appearance, but may also be a source of differences in microinfarct frequencies and numbers between studies. As such, this review demonstrates that there is an obvious need for standardization of neuropathological criteria for microinfarcts, to achieve better correspondence of findings from different laboratories in future studies.

The presence of microinfarcts was often correlated to small vessel disease represented by lacunar infarcts (Vinters et al, 2000; Rossi et al, 2004) and leukoencephalopathy on both neuropathological examination and brain computed tomography or MRI before death (Rossi et al, 2004; Longstreth et al, 2009). Furthermore, a few studies assessed patients with CAA and found an association with the occurrence of microinfarcts (Olichney et al, 1997; Soontornniyomkij et al, 2010; De Reuck et al, 2011a). Others found cortical vessels in immediate proximity to microinfarcts often to be engorged with amyloid (Haglund et al, 2006). Small vessel disease, as well as amyloid angiopathy, can cause marginal local brain perfusion (Pantoni, 2010). Moreover, cortical microinfarcts may be more common in the watershed areas (Suter et al, 2002; Strozyk et al, 2010). Therefore, microinfarcts could be related to intermittent focal ischemic episodes as a result of marginal brain perfusion. However, microinfarcts are also found in the brain regions supplied by large cerebral vessels and some studies found an association with macroscopic infarcts (Schneider et al, 2007a, 2007b; Troncoso et al, 2008; Longstreth et al, 2009; Arvanitakis et al, 2011). Therefore, some microinfarcts could also have an embolic origin, from ulcerated atherosclerotic plaques in large cerebral arteries. Nevertheless, at present the exact mechanisms underlying the occurrence of microinfarcts remain elusive.

Microinfarcts and other vascular damage of the cerebral parenchyma, with which they are associated, can result in lower cognitive performance. Indeed, microinfarcts seem to be associated with cognitive dysfunction and dementia. An explanation could be that microinfarcts themselves, because of neuronal loss, lead to intellectual decline. Disturbances in neuronal connectivity throughout the brain could also be the cause of cognitive dysfunction.

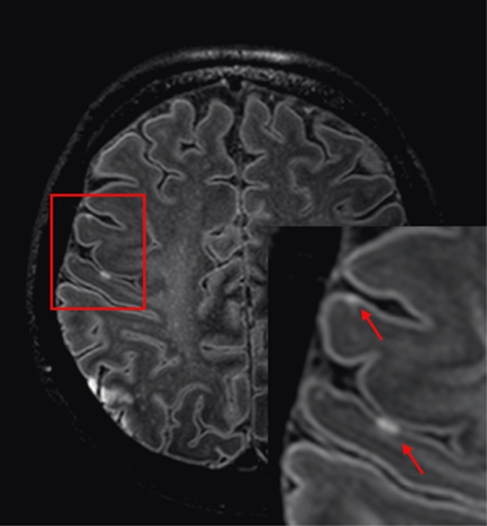

Because microinfarcts are correlated to vascular brain damage and dementia, detection of these lesions in vivo may have a high potential for future pathophysiological studies in vascular cognitive impairment. Detection in vivo would make it possible to investigate their evolution over time and their relationship with the development of cognitive impairment and dementia. Based on the neuropathological findings on microinfarcts, that is, their widespread appearance, differences in shape and the fact that they can appear as both gliotic and cystic lesions, it will be a challenge to recognize them on MR imaging. Nevertheless, with ultra-high field (7 T) MRI, we have already been able to visualize cortical hyperintense lesions, which may represent small ischemic lesions (Figure 3). To visualize microinfarcts on the brain MRI, one should focus on all brain regions, probably with particular attention for the watershed areas and cerebral cortex. Cystic microinfarcts would be hypointense on FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The more gliotic lesions will result in a hyperintense signal on both T2-weighted and FLAIR images. With the current resolution that can be achieved by a 7-T MRI scanner, microinfarcts are expected to give focal signal intensity changes in only one or a few voxels. Therefore, typical characteristics that can be seen in a histological biopsy will be difficult to recognize. Furthermore, up to the present, an inflammatory response can only be visualized on the brain MRI in experimental studies (Rausch et al, 2001; Petry et al, 2007). Future research should focus on radiological-pathological correlates in human as well.

Figure 3.

Example of cortical ischemic lesions on magnetic resonance (MR) images obtained at 7 T. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images from a 57-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation who presented with aphasia and left-sided hemiparesis based on cortical ischemia in the right middle cerebral artery territory. Note the small cortical hyperintensities (arrows), which represent minute acute ischemic lesions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Lon R White (Pacific Health Research Institute, Kuakini Medical Center, John A Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA) for his comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism website (http://www.nature.com/jcbfm)

This study was financially supported by a high potential grant from Utrecht University.

Supplementary Material

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct pathology, dementia, and cognitive systems. Stroke. 2011;42:722–727. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C, McKeith I, O'Brien J, Kalaria R, Jaros E, Ince P, Perry R. Neuropathological substrates of dementia and depression in vascular dementia, with a particular focus on cases with small infarct volumes. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11:59–65. doi: 10.1159/000017215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayne C, Richardson K, Matthews FE, Fleming J, Hunter S, Xuereb JH, Paykel E, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Huppert FA, O′Sullivan A, Dening T. Neuropathological correlates of dementia in over-80-year-old brain donors from the population-based Cambridge city over-75 s cohort (CC75C) study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:645–658. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Reuck J, Deramecourt V, Cordonnier C, Leys D, Maurage CA, Pasquier F. The impact of cerebral amyloid angiopathy on the occurrence of cerebrovascular lesions in demented patients with Alzheimer features: a neuropathological study. Eur J Neurol. 2011a;18:913–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Reuck J, Deramecourt V, Cordonnier C, Leys D, Pasquier F, Maurage CA. Prevalence of small cerebral bleeds in patients with a neurodegenerative dementia: a neuropathological study. J Neurol Sci. 2011b;300:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Ser T, Hachinski V, Merskey H, Munoz DG. Alzheimer's disease with and without cerebral infarcts. J Neurol Sci. 2005;231:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkinjuntti T, Haltia M, Palo J, Sulkava R, Paetau A. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of vascular dementia: a prospective clinical and post-mortem neuropathological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:1037–1044. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.8.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esiri MM, Wilcock GK, Morris JH. Neuropathological assessment of the lesions of significance in vascular dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:749–753. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.6.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebremedhin E, Rosenberger A, Rub U, Vuksic M, Berhe T, Bickeboller H, De Vos RA, Thal DR, Deller T. Inverse relationship between cerebrovascular lesions and severity of lewy body pathology in patients with lewy body diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:442–448. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d88e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold G, Bouras C, Canuto A, Bergallo MF, Herrmann FR, Hof PR, Mayor PA, Michel JP, Giannakopoulos P. Clinicopathological validation study of four sets of clinical criteria for vascular dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:82–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold G, Giannakopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bouras C, Kövari E. Identification of Alzheimer and vascular lesion thresholds for mixed dementia. Brain. 2007;130:2830–2836. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold G, Giannakopoulos P, Montes-Paixao JC, Herrmann FR, Mulligan R, Michel JP, Bouras C. Sensitivity and specificity of newly proposed clinical criteria for possible vascular dementia. Neurology. 1997;49:690–694. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold G, Kövari E, Herrmann FR, Canuto A, Hof PR, Michel JP, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Cognitive consequences of thalamic, basal ganglia, and deep white matter lacunes in brain aging and dementia. Stroke. 2005;36:1184–1188. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000166052.89772.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund M, Passant U, Sjobeck M, Ghebremedhin E, Englund E. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cortical microinfarcts as putative substrates of vascular dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:681–687. doi: 10.1002/gps.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isojima D, Togo T, Kosaka K, Fujishiro H, Akatsu H, Katsuse O, Iritani S, Matsumoto T, Hirayasu Y. Vascular complications in dementia with Lewy bodies: a postmortem study. Neuropathology. 2006;26:293–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaria RN, Kenny RA, Ballard CG, Perry R, Ince P, Polvikoski T. Towards defining the neuropathological substrates of vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2004;226:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kövari E, Gold G, Herrmann FR, Canuto A, Hof PR, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Cortical microinfarcts and demyelination affect cognition in cases at high risk for dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:927–931. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257094.10655.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kövari E, Gold G, Herrmann FR, Canuto A, Hof PR, Michel JP, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Cortical microinfarcts and demyelination significantly affect cognition in brain aging. Stroke. 2004;35:410–414. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110791.51378.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Olichney JM, Hansen LA, Hofstetter CR, Thal LJ. Small concomitant vascular lesions do not influence rates of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1474–1479. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.10.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstreth WT, Jr, Sonnen JA, Koepsell TD, Kukull WA, Larson EB, Montine TJ. Associations between microinfarcts and other macroscopic vascular findings on neuropathologic examination in 2 databases. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:291–294. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318199fc7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van BG, Berg L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer′s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien JT, Erkinjuntti T, Reisberg B, Roman G, Sawada T, Pantoni L, Bowler JV, Ballard C, DeCarli C, Gorelick PB, Rockwood K, Burns A, Gauthier S, DeKosky ST. Vascular cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Ihara M, Fujita Y, Ito H, Takahashi R, Tomimoto H. Cortical microinfarcts in Alzheimer's disease and subcortical vascular dementia. Neuro Report. 2009;20:990–996. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832d2e6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olichney JM, Ellis RJ, Katzman R, Sabbagh MN, Hansen L. Types of cerebrovascular lesions associated with severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;826:493–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:689–701. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry KG, Boiziau C, Dousset V, Brochet B. Magnetic resonance imaging of human brain macrophage infiltration. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch M, Sauter A, Frohlich J, Neubacher U, Radu EW, Rudin M. Dynamic patterns of USPIO enhancement can be observed in macrophages after ischemic brain damage. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:1018–1022. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R, Joachim C, Geroldi C, Combrinck M, Esiri MM, Smith AD, Frisoni GB. Association between subcortical vascular disease on CT and neuropathological findings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:690–695. doi: 10.1002/gps.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M, Gold G, Kövari E, Herrmann FR, Bozikas VP, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Differential impact of lacunes and microvascular lesions on poststroke depression. Stroke. 2009;40:3557–3562. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.548545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M, Gold G, Kövari E, Herrmann FR, Hof PR, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Neuropathological analysis of lacunes and microvascular lesions in late-onset depression. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2010;36:661–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007a;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JA, Boyle PA, Arvanitakis Z, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Subcortical infarcts, Alzheimer's disease pathology, and memory function in older persons. Ann Neurol. 2007b;62:59–66. doi: 10.1002/ana.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinka L, Kövari E, Gold G, Hof PR, Herrmann FR, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P. Small vascular and Alzheimer disease-related pathologic determinants of dementia in the oldest-old. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:1247–1255. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ffc3b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Brickell K, Crane PK, Woltjer R, Montine TJ, Craft S. Different patterns of cerebral injury in dementia with or without diabetes. Arch Neurol. 2009a;66:315–322. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Crane PK, Haneuse S, Li G, Schellenberg GD, Craft S, Leverenz JB, Montine TJ. Pathological correlates of dementia in a longitudinal, population-based sample of aging. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:406–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Haneuse S, Woltjer R, Li G, Crane PK, Craft S, Montine TJ. Neuropathology in the adult changes in thought study: a review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009b;18:703–711. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Walker RL, Haneuse S, Crane PK, Gray SL, Breitner JC, Montine TJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with increased neuritic plaques. Neurology. 2010;75:1203–1210. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f52db1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soontornniyomkij V, Lynch MD, Mermash S, Pomakian J, Badkoobehi H, Clare R, Vinters HV. Cerebral microinfarcts associated with severe cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:459–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00322.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strozyk D, Dickson DW, Lipton RB, Katz M, Derby CA, Lee S, Wang C, Verghese J. Contribution of vascular pathology to the clinical expression of dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1710–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter OC, Sunthorn T, Kraftsik R, Straubel J, Darekar P, Khalili K, Miklossy J. Cerebral hypoperfusion generates cortical watershed microinfarcts in Alzheimer disease. Stroke. 2002;33:1986–1992. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000024523.82311.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, Imai Y, Larson E, Graves A, Sugimoto K, Yamaguchi T, Sasaki H, Chiu D. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6:45–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso JC, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, Crain B, Pletnikova O, O'Brien RJ. Effect of infarcts on dementia in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:168–176. doi: 10.1002/ana.21413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinters HV, Ellis WG, Zarow C, Zaias BW, Jagust WJ, Mack WJ, Chui HC. Neuropathologic substrates of ischemic vascular dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:931–945. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.11.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Larson EB, Sonnen JA, Shofer JB, McCormick W, Bowen JD, Montine TJ, Li G. Blood pressure and brain injury in older adults: findings from a community-based autopsy study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1975–1981. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L. Brain lesions at autopsy in older Japanese-American men as related to cognitive impairment and dementia in the final years of life: a summary report from the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:713–725. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, Nelson J, Davis DG, Ross GW, Masaki K, Launer L, Markesbery WR. Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;977:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuereb JH, Brayne C, Dufouil C, Gertz H, Wischik C, Harrington C, Mukaetova-Ladinska E, McGee MA, O'Sullivan A, O'Connor D, Paykel ES, Huppert FA. Neuropathological findings in the very old. Results from the first 101 brains of a population-based longitudinal study of dementing disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;903:490–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip AG, McKee AC, Green RC, Wells J, Young H, Cupples LA, Farrer LA. APOE, vascular pathology, and the AD brain. Neurology. 2005;65:259–265. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168863.49053.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.