Abstract

Background

Methods for determining cost-effectiveness of different treatments are well established, unlike appraisal of non-drug interventions, including novel diagnostics and biomarkers.

Objective

The authors develop and validate a new health economic model by comparing cost-effectiveness of tuberculin skin test (TST); blood test, interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) and TST followed by IGRA in conditional sequence, in screening healthcare workers for latent or active tuberculosis (TB).

Design

The authors focus on healthy life years gained as the benefit metric, rather than quality-adjusted life years given limited data to estimate quality adjustments of life years with TB and complications of treatment, like hepatitis. Healthy life years gained refer to the number of TB or hepatitis cases avoided and the increase in life expectancy. The authors incorporate disease and test parameters informed by systematic meta-analyses and clinical practice. Health and economic outcomes of each strategy are modelled as a decision tree in Markov chains, representing different health states informed by epidemiology. Cost and effectiveness values are generated as the individual is cycled through 20 years of the model. Key parameters undergo one-way and Monte Carlo probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

Setting

Screening healthcare workers in secondary and tertiary care.

Results

IGRA is the most effective strategy, with incremental costs per healthy life year gained of £10 614–£20 929, base case, £8021–£18 348, market costs TST £45, IGRA £90, IGRA specificities of 99%–97%; mean (5%, 95%), £12 060 (£4137–£38 418) by Monte Carlo analysis.

Conclusions

Incremental costs per healthy life year gained, a conservative estimate of benefit, are comparable to the £20 000–£30 000 NICE band for IGRA alone, across wide differences in disease and test parameters. Health gains justify IGRA costs, even if IGRA tests cost three times TST. This health economic model offers a powerful tool for appraising non-drug interventions in the market and under development.

Article summary

Article focus

Methods for determining cost-effectiveness of different treatments are well established unlike the appraisal of non-drug interventions, including novel diagnostics and biomarkers.

We develop and validate a new health economic model by comparing cost-effectiveness of tuberculin skin test (TST) and/or a tuberculosis (TB) blood test, interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA), in screening healthcare workers for latent or active TB.

We investigate gains in healthy life years, without TB or hepatitis, in a comprehensive model informed by epidemiology, meta-analysis and clinical practice, testing disease and test parameters by one-way and Monte Carlo probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

Key messages

IGRA is the most effective strategy when screening healthcare workers for latent or active TB.

IGRA screening has an incremental cost per healthy life year gained of £10 614–£20 929, base case, £8021–£18 348, market costs, TST £45, IGRA £90, IGRA specificities 99%–97%; mean (5%, 95%), £12 060 (£4137–£38 418) by Monte Carlo analysis.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Screening with IGRA alone appears cost-effective since incremental costs per healthy life year gained, a conservative estimate of benefit, are at the lower end of the £20 000–£30 000 NICE band.

Neither TST nor IGRA differentiate latent from active TB, and the specificity of IGRA is inferred from studies in populations at low risk of TB.

These findings are robust for wide differences in disease and test parameters, such as if IGRA test costs are three times TST costs, suggesting that this health economic model is a powerful tool for appraising non-drug interventions in the market and under development.

Introduction

Economic evaluation is a recognised approach to optimising national healthcare provision within a limited budget, but informed choice requires transparent analysis highlighting key assumptions and critical factors.1 Methods for determining the cost-effectiveness of different treatments are well established,2 3 unlike the appraisal of non-drug interventions, including novel diagnostics and biomarkers. We develop and validate a new health economic model by focusing on whether a tuberculin skin test (TST) and/or a blood test for tuberculosis (TB), interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA), is more cost-effective in screening healthcare workers for latent or active TB. The screening of healthcare workers for TB has economic importance given the impact of disease transmission in each case together with the large number of NHS employees at risk, 1.7 million personnel and 80 000 new employees per annum (NHS, 2010). We inform the health economic model by applying insight from epidemiology, meta-analysis and clinical practice including knowledge of market costs to compare the cost-effectiveness of new technology supporting or replacing established practice. The analysis is from the NHS and societal perspective.

Established practice is for trained occupational health staff to administer a TST using cheap readily available reagents injected intradermally at an initial visit. The skin test reaction is measured at a second clinic visit 48–72 h later.4 The need for two visits is operationally inefficient, and the test itself is limited both by specificity and sensitivity. TST has a low specificity in subjects exposed to BCG vaccination or environmental non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) and moderate sensitivity resulting in false negatives.5 6 A new technological approach requires a single clinic visit to draw a blood sample which is transferred to the laboratory for analysis in a TB-specific IGRA.7 The approach is operationally efficient, and the assay has a high specificity and sensitivity, although simple costs per test are greater than the TST. In principle, the advantages of old and new might be combined using TST for all and then applying IGRA blood testing to TST-positive cases to exclude false-positive TST after previous exposure to NTM including BCG immunisation. Following earlier work,8 this study has focused on healthy life years gained as the benefit metric, rather than quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). The reason is the lack of robust data to estimate quality adjustments of life years with TB and complications of treatment such as hepatitis. Healthy life years gained refers to the number of TB or hepatitis cases avoided and the associated increase in life expectancy.

This study adds to the literature8–11 in four key areas by incorporating:

healthy life years to avoid the assumptions inherent in estimating QALYs;

-

key disease parameters in a comprehensive model of all relevant health states informed by epidemiology including

-

key test parameters relevant to clinical practice including

and we provide a powerful methodology for appraising the cost-effectiveness of non-drug interventions to inform healthcare policy, including sensitivity analyses of key parameters.

Methods

The health and economic outcomes of the three alternative testing strategies are modelled as a decision tree, representing the health outcomes of each of the strategies as Markov chains over 20 years. The model incorporates economic, medical, epidemiological and operational factors in the analysis. This approach lends itself to the clinical setting where the risks are continuous over time, key events may be repeated and operational factors may interact with other key parameters to influence the base case result.

Data collection

The test, population and outcome characteristics (table 1) include data from the meta-analyses by Menzies et al15 and Pai et al.5 In the absence of a gold standard for LTBI, active TB is used as a surrogate to determine assay sensitivity.15 Specificity for LTBI is derived by testing populations at low risk of TB5 16 20 to determine the rate of false positives. The analysis is guided by our clinical and market experience with the T-Spot TB test, applying an IGRA specificity of 98%16 for the base case. We then examine the impact of IGRA specificity in the sensitivity analyses of the cost-effectiveness model. The operational characteristics of the three alternative approaches include repeat test rates due to test failure and failure to attend for skin test reading. Direct and indirect costs are shown (table 2) drawing on data supplied by NICE21 (see appendix 6), the Cambridge TB service and the NHS National tariff 201022 with costs adjusted to the 2010–2011 financial year (supplementary table 1). The impact of regional or national differences in disease parameters and costs are examined in one-way-sensitivity analyses. The impact of uncertainty within multiple parameters is then examined using Monte Carlo probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Table 1.

Base case data for test, population and outcomes parameters

| Parameter | Base case values | Range tested | Reference |

| 1. Test characteristics | |||

| TST | |||

| Specificity | 0.66 | 0.46–0.86 | 15 |

| Sensitivity | 0.70 | 0.65–0.74 | 15 |

| Probability a second TST is placed | 0.1737 | 0.025–0.25* | 14 |

| TB-specific IGRA | |||

| Specificity | 0.98 | 0.90–0.99 | 16 |

| Sensitivity | 0.90 | 0.82–0.98 | 5 |

| Probability a second IGRA is required | 0.0343 | 0.015–0.15* | 14 |

| 2. Population characteristics | |||

| Age range | 20–30 | ||

| Occupation | Healthcare worker | ||

| BCG vaccination rates | 52.8% | 17 | |

| Nationality of majority | English | ||

| Prevalence of LTBI | 0.035 | 0.035–0.35* | 17 |

| Prevalence of TB | 0.0001 | 0.0001–0.001* | 18 |

| Probability of all causes of death | 0.0045 | 0.0045–0.045* | Office for National Statistics 2008 |

| 3. Probability of outcomes | |||

| Efficacy of LTBI treatment | 0.65 | 19 | |

| Risk of hepatitis caused by treatment | 0.0177 | 0.0177–0.177* | 12 |

| Risk of activation of LTBI | 0.01 | 6 | |

| Probability of relapse of TB | 0.0315 | 0.0315–0.315* | 13 |

| Probability of death due to TB | 0.018 | 0.018–0.18* | 18 |

| Probability of death due to hepatitis | 0 | Assumption | |

10-fold range tested in sensitivity analyses to highlight potential impact on incremental cost per healthy life year gained.

IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Table 2.

Costs

| Parameter | Base case values | Range tested |

| 1. Cost of interventions | NICE21 | |

| TST | £16 | £16–£64 |

| IGRA | £44.78 | £30–£120 |

| Chest radiograph | £28 | |

| Cambridge TB Service 2010 NHS National Tariff22 | ||

| TB treatment | £1637 | 0.5–2 times |

| Contact tracing | £426 | 0.5–2 times |

| LTBI treatment | £647 | 0.5–2 times |

| Hepatitis treatment | £640 | 0.5–2 times |

| 2. Healthcare worker costs | Cambridge TB Service 2010 NHS Pay 2/201023 | |

| Time to attend for TB treatment | £662 | 0.5–2 times |

| Time to attend for contact tracing | £95 | 0.5–2 times |

| Time to attend for LTBI treatment | £172 | 0.5–2 times |

| Time for hepatitis treatment | £114 | 0.5–2 times |

| 3. Discount rate | 0.05 |

TB treatment costs are derived from the NHS National Tariff 2010–201122 applied to the Cambridge TB service. Healthcare worker costs are derived from the NHS Pay Circular (AforC) 2/2010,23 point 26 £30 460, plus 22% overheads £37 161 per annum, applied to the Cambridge TB service. Total model costs for TB treatment are TB treatment, plus contact tracing ×5 contacts per case,19 plus healthcare worker time costs, £4908; for LTBI, LTBI treatment plus healthcare worker time costs, £819 and for hepatitis, hepatitis treatment plus healthcare worker time costs, £755 (supplementary table 1).

IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Model construction

We built a decision analysis model, which incorporates the health outcomes as Markov chains over 20 years, to analyse three different diagnostic approaches to LTBI. This model only considers the initial screening for newly hired personnel; the annual testing is beyond the scope of this model. The model is coded and composed using the decision analysis software TreeAge Pro Suite 2009, 2011. The states of the Markov chains represent the health conditions of the individuals, following a LTBI diagnosis test and possible interventions. Each Markov state length is 1 year. The decision is made at the first node of the decision tree between three diagnosis options: TST, IGRA and a combined sequential testing strategy. The alternatives are assessed according to their cost and effectiveness values over 20 years, in which the costs are direct and indirect monetary costs and their effectiveness is measured by total number of healthy years. The Markov chain is implemented through 20 years; related cost and effectiveness values due to different health states are recorded as the individual is cycled through the model. All future costs are discounted at 5% per year. This Markov model assumes the following

Each health state is taken as a time period of 1 year, cannot be left earlier and can only last longer if the return probability is greater than zero.

All patients with positive results for LTBI accept treatment, consistent with conditions of employment in the NHS. The impact of limited compliance is allowed for within the efficacy of LTBI treatment.19

Standard isoniazid and rifampicin treatment for LTBI lasts 3 months and all treatments are completed.

Diagnostic tests are repeated once only as required to achieve a result.

The repeat rate for diagnostic tests is further addressed in the sensitivity analyses.

The probability that LTBI generates a positive result is assumed to be the same as the probability that active TB generates a positive result, as there is no gold standard for LTBI.

The risk of active TB in cases with false-negative results is proportional to the prevalence rates of latent and active TB.

The result of the second test is independent of the first in two-stage testing.

The effects of TB and Hepatitis are the simple sum, rather than synergistic.

All cases with positive TST or IGRA will have a chest radiograph that identifies all cases of active TB. All positive chest radiographs are active TB.

The relapse rate of TB is higher than the prevalence rate in the general population for the first 3 years after recovery.13

The probability of continuing to have TB after standard TB treatment is the probability of relapse.

All TB is diagnosed and treated on time. The effect of late diagnosis of latent or active TB in cases with false-negative results is neglected.

An equal number of males and females make up new NHS healthcare workers.

Death of an employee has no monetary cost for NHS.

Transmission of TB to the community is modelled as a constant monetary cost for contact tracing, including screening the close contacts of the patient and their treatment in the case of positive TB findings.

All employees are employed for 20 years.

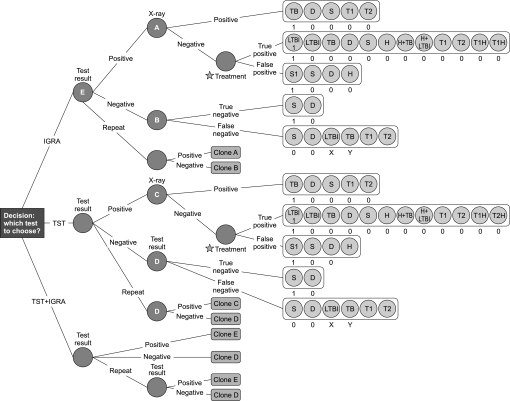

The comprehensive decision tree consists of 985 nodes including three similar sub-trees with different probability and cost parameters (figure 1). The initial analysis was then subjected to one-way sensitivity analyses applied to key parameters including IGRA sensitivity and specificity; prevalence rates of TB and LTBI; all-cause death rates; test repetition rates; market rates for TST and IGRA tests and treatment costs for TB, LTBI and hepatitis. We tested the impact of variation in multiple parameters by first generating triangular distributions using minimum, mode or peak and maximum values for key parameters.24 Probabilistic sensitivity analysis was then carried out by Monte Carlo simulation using 100 000 iterations to estimate the total impact of uncertainty on the model, TreeAge Pro 2011.

Figure 1.

The decision tree. Health and economic outcomes of tuberculin skin test and/or IGRA modelled as a decision tree in Markov chains representing different health states informed by epidemiology: TB, active tuberculosis; LTBI, LTBI1, latent tuberculosis, with treatment; D, Death; S, S1, healthy, with unnecessary treatment for LTBI; H, H + TB, H + LTBI, hepatitis and TB or LTBI; T1, T2, T1H, T2H, transition states indicating relapse rates within 3 years of treatment and thereafter, with hepatitis; A–E, node points repeated as Clones A–E. X, Y are probabilities, p, X = pLTBI/(pLTBI + pTB), Y = pTB/(pLTBI + pTB).

Results

Base case analysis indicates that the incremental cost of IGRA alone is offset by the increased effectiveness of this approach over the two-stage sequential approach of TST followed by IGRA for positive TST results (table 3a). IGRA is the most effective strategy with an incremental effectiveness of 0.0015 and an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £15 757 per healthy life year gained. The strategy of TST alone is clearly inferior by all criteria. We therefore focused on further analysis of parameters affecting the relative efficacy of TST + IGRA versus IGRA alone.

Table 3.

Incremental costs per healthy life year gained (ICER) of IGRA or TST

| Strategy | Cost | Incremental cost | Effectiveness | Incremental effectiveness | Cost/effectiveness | ICER |

| a. Base case | ||||||

| IGRA + TST | £76.60 | £0.00 | 19.07569 | 0 | 4.02 | £0 |

| IGRA | £99.52 | £22.92 | 19.07714 | 0.001455 | 5.22 | £15 757 |

| TST | £333.42 | £233.90 | 19.07088 | −0.00626 | 17.48 | −£37 358 |

| (Dominated) | ||||||

| b. Market costs | ||||||

| IGRA + TST | £127.13 | £0.00 | 19.0757 | 0 | 6.66 | £0 |

| IGRA | £146.29 | £19.16 | 19.0771 | 0.00145 | 7.67 | £13173 |

| TST | £367.45 | £221.16 | 19.0709 | −0.0063 | 19.27 | −£35324 |

| (Dominated) | ||||||

Base case, TST £16, IGRA £45; market costs TST £45, IGRA £90.

ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Sensitivity analyses of disease and test parameters

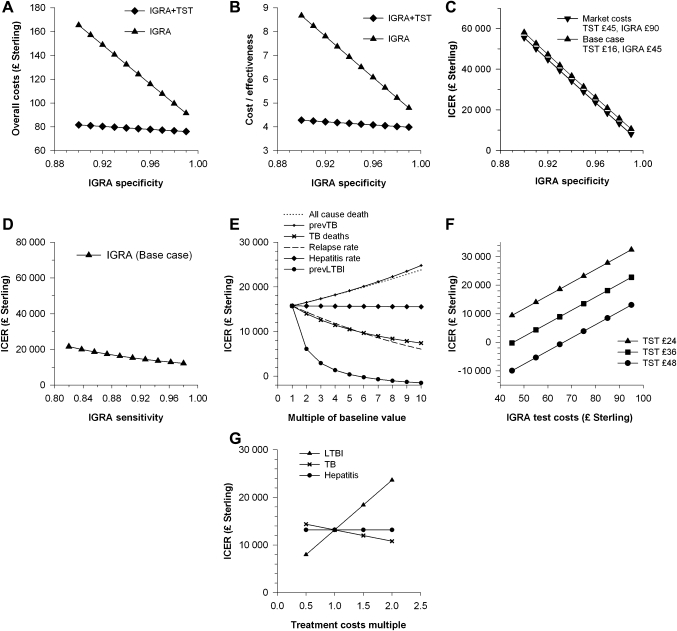

Sensitivity analysis of the base case model indicates that the ICER for IGRA ranges from £20 929 to £10 614 per healthy life year gained for test specificities of 97%–99% (figure 2A–C, supplementary table 2). Assay sensitivity has a much smaller impact on the ICER (figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Impact of wide differences in disease and test parameters on cost-effectiveness. (A–C) IGRA specificity versus (A) overall costs in £ Sterling, (B) cost/effectiveness, (C) ICER, incremental cost per healthy life year gained, (D–F) ICER in the base case model versus (D) IGRA sensitivity, (E) key disease parameters increased times 10, prev, prevalence, (F) tuberculin skin test and IGRA costs and (G) ICER in the market case model versus fourfold variation in treatment costs.

The superior cost-effectiveness of IGRA was not threatened when base case values were inflated 10-fold for all-cause death rates, TB death rates, prevalence of LTBI or TB, relapse rates and hepatitis rates (figure 2E, supplementary table 3a–f).

TST repeat rates were estimated using the 17.4% rate of failure to achieve a TST result in a UK study of routine practice.14 This compares with 53%, 35/66, of medical students who failed to attend their first Mantoux appointment25 and a 12% failure rate to read the first TST.11 Varying the IGRA repeat rate from 1.5% to 15% or TST repeat rate from 2.5% to 25% had little impact on the ICER which increased from £15 573 to £16 860 and £14 242 to £16 776 per healthy life year gained, respectively (supplementary table 3g, h).

The cost of TST testing was investigated by eliciting costs from five private medical service providers, median £65 per test, range £45–£75, and by using estimated itemised costs from Occupational Health and Safety Service, University of Cambridge (supplementary, table 1V), total cost £48.53. We used £45 as a market cost for TST and tested the impact of test costs on ICER. Market costs for TST significantly enhance the ICER for IGRA alone across a range of IGRA costs (figure 2F, supplementary table 4). In particular, the market standard test costs of £45 per TST and £90 per IGRA generate an ICER of £13 173 per healthy life year gained (table 3b). A threshold value of £30 000 per healthy life year gained is still achieved when IGRA test costs are three times TST test costs.

Examining the impact of assay specificity and sensitivity, this market standard model generates a range of £18 348–£8021 per healthy life year gained for an IGRA specificity of 97%–99%. Sensitivity analysis for TST test characteristics over a range of 0.46–0.86 for specificity and 0.65–0.74 for sensitivity15 suggests that IGRA remains the optimal strategy with costs of £354–£31 069 and £10 385–£16 484 per healthy life year gained, respectively (supplementary table 5).

The calculation and apportionment of treatment costs is likely to vary between centres, but a fourfold variation, 0.5–2 times baseline, in treatment costs for LTBI, TB or hepatitis is also accommodated by the market standard model (figure 2G, supplementary table 6).

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis by Monte Carlo simulation was carried out with uncertainty in each of 12 key parameters defined as triangular distributions (supplementary table 7). Mean incremental cost per healthy life year gained was £12 060, with 5% and 95% values of £4137 and £38 418, respectively.

Discussion

The methodology for determining the cost-effectiveness of different treatments is well established1–3 in contrast to the analysis of non-drug interventions. Our health economic model suggests a methodology to appraise the host of novel diagnostics7 and biomarkers generated by clinical science. Healthy life years, despite being a conservative benefit metric, may be particularly useful in evaluating novel screening and monitoring tests by avoiding the assumptions inherent in generating QALYs.1 8 11 26 27 This approach, allied to the use of multiple disease states supported by epidemiological data, is far more powerful than standard comparisons since the IGRA strategy will overcome a twofold to threefold excess of simple test costs.

In our study, we compare the effectiveness of the diagnostic procedures by focusing on healthy life years gained,1 8 rather than QALYs.11 21 26 The reason is there are limited data to base estimates of QALYs for each of the health states applicable to latent or active TB and its treatment.28 The additional costs of IGRA alone appear justified by the health gains at £15 757 per healthy life year gained, falling to £13 173 per healthy life year when applying market costs where blood tests cost twice as much as skin tests. Our estimates are conservative in that they only take a healthy life year as a benefit (ie, years without TB or hepatitis). Since the calculated ratio is at the lower end of the NICE band of £20 000–£30 000, IGRA is cost-effective, even at the current NICE threshold which may or may not be conservative.2 3 These findings are supported by the probabilistic sensitivity analysis of multiple disease and test parameters. There is no validated instrument for determining quality of life with TB,29 but when such data are available, it is likely that additional health gains would be identified, further improving the cost/benefit ratio.

The health economic model is sensitive to IGRA specificity, which is derived from estimates of false positives in populations at low risk of TB.16 27 30 An IGRA specificity of 98% is conservative by current literature16 27 30 but higher than analyses potentially confounded by data from studies in populations at intermediate rather than low risk of TB.5 20 21 Our model accommodates substantial enhancement of TST specificity greater than expected in BCG-vaccinated populations or mixed populations including non-BCG-vaccinated healthcare workers.15 The outcome may be different in non-BCG-vaccinated populations with low NTM infection rates,5 but NTM infection is an increasing problem in adults.31 Studies testing children prior to BCG immunisation have revealed false-positive TST rates of 14% in South East England32 and 79% in Norway.33 It seems likely therefore that previous infection with NTM has a significant role in reducing the specific of TST. The study's findings accommodate wide regional or national differences in disease parameters, although health gains are enhanced by a relative increase in the prevalence of LTBI and hampered by doubling costs for the treatment of LTBI.

Studies including the RR of progression to active TB suggest additional limits to TST specificity, reviewed recently.34 IGRA-positive cases with LTBI are more likely to progress to active TB than TST-positive cases. In particular, IGRA-positive cases showed a 19% greater chance of progression to active TB than expected solely from the increased specificity of IGRA over TST.10 This advantage would lead to further domination of TST-only approaches, by sequential TST then IGRA and IGRA-alone strategies.

The one-stop approach of IGRA alone has additional operational advantages, which are likely to enhance the value of this strategy. Testing at a single visit boosts compliance while minimising consumption of resources to achieve a test result and the risk of loss to follow-up. The health economic model does not include an allowance for healthcare workers' time to attend for testing, but these staff costs would be greater when two to three visits are required for TST then IGRA further limiting cost-effectiveness of strategies incorporating TST. Efficiency is enhanced by combining IGRA with other screening blood tests, although a blood sample is more invasive than TST. Blood testing may offer more flexibility than TST with blood sampling facilities widely available in primary care and hospital settings. In contrast, carrying out a TST requires registered nurses with proven competence and recent training or administration of TSTs,4 which is more expensive than phlebotomy and may be limiting during peaks in demand such as in contact tracing. An IGRA strategy transfers costs from the clinic to the laboratory, where cost pressures are intense but responsive to focusing expertise and optimising staffing structures. Critical aspects of blood sampling are defined including the impact of the test population and sampling conditions on the performance characteristics of IGRA.14 35–37 An IGRA strategy also avoids the possibility of TST boosting TST responses after repeat testing6 or IGRA responses if follow-up testing is delayed.36 The relative merits of different IGRA tests are controversial,5 16 27 but where there is a consensus on the assay characteristics, this model should allow further investigation.

Our study suggests that health gains justify IGRA costs when screening healthcare workers for latent or active TB. These findings are robust for wide differences in key disease and test parameters, such as if IGRA test costs are three times TST costs, while maintaining cost-effectiveness at the lower end of the £20 000–£30 000 NICE band. We suggest that this health economic model incorporating healthy life years gained, epidemiology, meta-analyses and clinical practice provides a powerful tool for assessing the potential impact of new technology on established practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary-Jane Robinson, Occupational Health Nurse Manager, Occupational Health and Safety Service, University of Cambridge, for sharing data prior to presentation; Edward Mwarangu, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, for discussing costs during consultation prior to publication of CG117; Emma Harris, Nurse Specialist, University Hospitals Cambridge TB service, for help in generating treatment cost and Victoria Stoneman, Research and Development, Papworth Hospital, for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

To cite: Eralp MN, Scholtes S, Martell G, et al. Screening of healthcare workers for tuberculosis: development and validation of a new health economic model to inform practice. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000630. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000630

Contributors: ARE and RW conceived the study. SS and MNE developed the economic model with additional clinical data from GM, ARE and RW. MNE, SS and ARE tested and revised the economic model. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and approved the final version of the manuscript drafted by MNE, SS, RW, and ARE.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MNE, SS, GM and RW have no competing interests. ARE is the director of the specialist Immunology Laboratory at Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust which provides a supra-regional service for interferon-gamma release assays using the T-Spot TB test (Oxford Immunotech).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The economic model run on TreeAge Pro is available from the corresponding author. Data deposited in the Dryad repository: doi:10.5061/dryad.7576g50f

References

- 1.Trunz BB, Fine P, Dye C. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet 2006;367:1173–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towse A. Should NICE's threshold range for cost per QALY be raised? Yes. BMJ 2009;338:b181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raftery J. Should NICE's threshold range for cost per QALY be raised? No. BMJ 2009;338:b185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vivian C, NHS Policy for Occupational Health Management of Tuberculosis. NHS Plus, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an Update. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:177–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mack U, Migliori GB, Sester M, et al. LTBI: latent tuberculosis infection or lasting immune responses to M. tuberculosis? A TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J 2009;33:956–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lalvani A. Diagnosing tuberculosis infection in the 21st century: new tools to tackle an old enemy. Chest 2007;131:1898–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diel R, Wrighton-Smith P, Zellweger JP. Cost-effectiveness of interferon-{gamma} release assay testing for the treatment of latent tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 2007;30:321–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diel R, Nienhaus A, Lange C, et al. Cost-optimisation of screening for latent tuberculosis in close contacts. Eur Respir J 2006;28:35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diel R, Schaberg T, Loddenkemper R, et al. Enhanced cost-benefit analysis of strategies for LTBI screening and INH chemoprevention in Germany. Respir Med 2009;103:1838–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Perio MA, Tsevat J, Roselle GA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of interferon gamma release assays vs tuberculin skin tests in health care workers. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:179–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong Kong Chest Service/Tuberculosis Research Centre, Madras/British Medical Research Council A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of three antituberculosis chemoprophylaxis regimens in patients with silicosis in Hong Kong. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.British Thoracic Society A controlled trial of 6 months' chemotherapy in pulmonary tuberculosis. Final report: results during the 36 months after the end of chemotherapy and beyond. Br J Dis Chest 1984;78:330–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dosanjh DP, Hinks TS, Innes JA, et al. Improved diagnostic evaluation of suspected tuberculosis in routine practice. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:325–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menzies D, Pai M, Comstock G. Meta-analysis: new tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:340–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diel R, Goletti D, Ferrara G, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2011;37:88–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schablon A, Beckmann G, Harling M, et al. Prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection among health care workers in a hospital for pulmonary diseases. J Occup Med Toxicol 2009;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health Protection Agency Tuberculosis in the U.K. Annual Report on Tuberculosis Surveillance in the U.K. 2009. HPA Reports 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions Tuberculosis: Clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis and measures for its prevention and control. Royal College of Physicians, London; 2006; ISBN 1 86016 227 0. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee K, Han MK, Choi HR, et al. Annual Incidence of latent tuberculosis infection among newly employed nurses at a tertiary care University hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:1218–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Clinical diagnosis and management of Tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. NICE Clinical Guidelines 2011;CG117:1–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Health Payment by Results: National Tariff 2010-11. Guidance. 2010. dh_115898.xls. [Google Scholar]

- 23.NHS Pay circular (AforC) 2/2010. The NHS Terms and Conditions of Service Handbook, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox MP, Lash TL, Greenland S. A method to automate probabilistic sensitivity analyses of misclassified binary variables. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:1370–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martell G, Robinson MJ. Inefficiencies and delays in healthcare worker screening for Mycobacterium tuberculosis—an audit of medical student screening. 3rd HPA Pointers (Prevention of Occupational Infections, Treatment and Exposure Reporting Strategies for Healthcare Workers) Conference. London, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griebsch I, Coast J, Brown J. Quality-adjusted life-years lack quality in pediatric care: a critical review of published cost-utility studies in child health. Pediatrics 2005;115:e600–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pooran A, Booth H, Miller RF, et al. Different screening strategies (single or dual) for the diagnosis of suspected latent tuberculosis: a cost effectiveness analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2010;10:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller TL, McNabb SJN, Hilsenrath P, et al. Personal and societal health quality lost to tuberculosis. PLoS One 2009;4:e5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo N, Marra F, Marra CA. Measuring health-related quality of life in tuberculosis: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bienek DR, Chang CK. Evaluation of an interferon-gamma release assay, T-SPOT.TB, in a population with a low prevalence of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009;13:1416–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fowler SJ, French J, Screaton NJ, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in bronchiectasis: prevalence and patient characteristics. Eur Respir J 2006;28:1204–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weir RE, Fine PE, Nazareth B, et al. Interferon-gamma and skin test responses of schoolchildren in southeast England to purified protein derivatives from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other species of mycobacteria. Clin Exp Immunol 2003;134:285–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winje BA, Oftung F, Korsvold GE, et al. School based screening for tuberculosis infection in Norway: comparison of positive tuberculin skin test with interferon-gamma release assay. BMC Infect Dis 2008;8:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nienhaus A, Schablon A, Costa JT, et al. Systematic review of cost and cost-effectiveness of different TB-screening strategies. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrara G, Losi M, D'Amico R, et al. Use in routine clinical practice of two commercial blood tests for diagnosis of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a prospective study. Lancet 2006;367:1328–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Zyl-Smit RN, Pai M, Peprah K, et al. Within-subject variability and boosting of T-cell interferon-{gamma} responses after tuberculin skin testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrera V, Yeh E, Murphy K, et al. Immediate incubation reduces indeterminate results for QuantiFERON-TB Gold in-tube assay. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:2672–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.