Abstract

Objective

To evaluate gender differences in the prognostic value of renal function for mortality in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI).

Design

Prospective single-center cohort.

Setting

Single tertiary referral center in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Patients consecutive STEMI patients undergoing PPCI (1412 men and 558 women).

Main outcome measure

The authors calculated adjusted HRs for 3-year all-cause mortality according to the presence of a reduced renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min) using Cox proportional hazards models. In order to investigate a possible gender difference in the prognostic value of a reduced renal function, a comparison was made between the HRs of male and female patients and an interaction term was added to the model and tested for significance. Adjustments were made for age, body mass index, history of diabetes or hypertension, systolic blood pressure and heart rate, anterior myocardial infarction and time to treatment.

Results

In male patients, a reduced renal function was associated with increased 3-year mortality (adjusted HR 6.31, 95% CI 3.74 to 10.63, p<0.001). A reduced renal function was associated with a twofold increase in the mortality hazard in female patients (adjusted HR 2.22, 95% CI 1.25 to 3.94, p=0.006).

Conclusions

In this large single-centre registry of STEMI patients undergoing PPCI, renal dysfunction as assessed by estimated glomerular filtration rate had prognostic significance for mortality in both male and female patients.

Article summary

Article focus

To evaluate gender differences in the prognostic value of renal function in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Key message

Renal dysfunction has prognostic significance for mortality in both male and female patients.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Renal function was routinely measured at admission in a large tertiary referral center.

Single-center cohort and information on the cause of death was not available.

Introduction

Even in mild forms, renal dysfunction as assessed by the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is a major risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction.1 Renal dysfunction is more prevalent among women presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), although female patients presenting with STEMI are generally older and have more comorbidities when compared with male patients.1 2 A recently performed single-centre study in Sweden showed a clear gender difference in the prevalence and prognostic impact of renal insufficiency in STEMI patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI).3 In this cohort, 67% of female patients had renal insufficiency, defined as an eGFR <60 ml/min, compared with 26% of the male patients. Moreover, a prognostic impact of renal insufficiency on 1-year mortality was only observed in female patients, even after adjustments for baseline differences between both genders. This counterintuitive finding deserves confirmation. In the current manuscript, the main objective was to evaluate gender differences in the relation between renal function and outcomes in STEMI patients undergoing PPCI in a large single centre in the Netherlands.

Methods

Source population and procedures

We used data from consecutive STEMI patients who underwent PPCI in our centre between 1 January 2005 and 1 January 2009. The PPCI and adjunctive pharmacological treatment were performed according to ACC/AHA and ESC guidelines. In general, patients were eligible for PPCI if they presented with ischaemic chest pain, onset of symptoms ≤12 h prior to presentation and at least 1 mm of ST-segment elevation in two contiguous leads on the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Patients received aspirin (500 mg), clopidogrel (300–600 mg) and unfractioned heparin (5000 IU). Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used at the discretion of the operator. If a coronary stent was implanted, clopidogrel was prescribed for at least 1 month to patients with a bare metal stent and for at least 6 months following a dug-eluting stent.

eGFR and biomarkers

Blood samples prior to PPCI were obtained as part of routine clinical care. Blood samples were drawn immediately after insertion of the arterial sheath prior to PPCI for assessment of cardiac troponin T (cTnT), C reactive protein, glucose, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) and plasma creatinine. Blood samples were centrifuged without undue delay and analysed. Both cTnT and NT-pro-BNP were measured using a Hitachi modular E-170 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). C reactive protein was measured with an immunoturbidimetric assay, and glucose and plasma creatinine were measured with an enzymatic assay on a Hitachi modular P-800 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH). The eGFR was calculated according to the Cockcroft and Gault formula.4 For our current study, an eGFR of 60 ml/min was defined as a reduced renal function.5

Data collection

Our local catheterisation laboratory database was consulted for information about the patients' demographics, procedural and angiographic characteristics that had been prospectively collected and entered by interventional cardiologists and specialised nurses.

Study population

For the current analysis, we included all STEMI patients who underwent PPCI between 1 January 2005 and 1 January 2009 and had eGFR measured prior to percutaneous coronary intervention. Patients in whom we were not able to calculate an eGFR were excluded. Only the first PPCI was included in case of a patient with multiple PPCIs within the time window (n=66). We excluded STEMI patients undergoing rescue percutaneous coronary intervention after failed thrombolysis (n=28). Ten patients were removed because they had symptoms lasting longer than 12 h.

Outcomes

The outcome for our current analysis was all-cause mortality. Information on vital status obtained from the institutional database was synchronised with the Dutch national population registry.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables were compared with the Student t test and skewed-distributed variables with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test. Follow-up was right censored at 3 years or at last known follow-up, whichever came first. The prognostic value of eGFR was assessed by investigating the relation between mortality and eGFR in two sets of Cox proportional hazards analyses: univariable analyses and multivariable analysis with adjustments for age or established predictors of mortality (complete case analysis). The following established prognostic factors derived from the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) score were included in the model: age, body weight, history of diabetes, hypertension, systolic blood pressure and heart rate, anterior myocardial infarction and time to treatment (symptom onset to first balloon inflation).6 7 The interaction between gender and renal function was assessed by entering an interaction term in the Cox proportional hazards model. In an exploratory analysis, we added NT-pro-BNP, glucose and shock to the established predictors in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. Both biomarkers were added as categorical variables according to previously described cut-offs.8 Cumulative event rates were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. We plotted Kaplan–Meier curves for the following categories: eGFR <45 ml/min, eGFR 45–59 ml/min and eGFR ≥60 ml/min.9 A p value of <0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

We included 1970 patients with a measured eGFR in our current study. Of these patients, 1412 (71.7%) were men and 558 (28.3%) were women. The baseline characteristics of the study patients are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study patients according to gender and renal function

| Characteristics | Men (n=1412) |

Women (n=558) |

p Value* | ||||

| eGFR <60 ml/min (n=124) | eGFR ≥60 ml/min (n=1288) | p Value | eGFR <60 ml/min (n=138) | eGFR ≥60 ml/min (n=420) | p Value | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age (year) | 75± (9) | 59± (12) | <0.001 | 78± (9) | 62± (13) | <0.001 | 0.005 |

| Body mass index | 25± (3.7) | 27± (3.8) | <0.001 | 25± (3.9) | 28± (10) | <0.001 | 0.19 |

| Risk factors | |||||||

| Current smoking | 33 (27%) | 560 (44%) | <0.001 | 25 (18%) | 179 (41%) | <0.001 | 0.098 |

| Hypertension | 48 (39%) | 360 (28%) | 0.012 | 62 (45%) | 144 (34%) | 0.025 | 0.31 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 19 (15%) | 264 (21%) | 0.17 | 21 (15%) | 99 (24%) | 0.04 | 0.98 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (16%) | 126 (10%) | 0.027 | 29 (21%) | 62 (15%) | 0.085 | 0.31 |

| Clinical history | |||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 38 (36%) | 163 (13%) | <0.001 | 28 (22.0%) | 36 (9.3%) | <0.001 | 0.025 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 25 (21%) | 126 (10%) | <0.001 | 8 (6.1%) | 31 (7.6%) | 0.55 | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 4 (3.5%) | 22 (1.8%) | 0.19 | 5 (3.8%) | 8 (2.0%) | 0.24 | 0.91 |

| Laboratory assessments | |||||||

| Troponin T (μg/l) | 0.04 (0.09–0.59) | 0.04 (0.04–0.20) | <0.001 | 0.15 (0.04–0.74) | 0.05 (0.04–0.26) | 0.001 | 0.15 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 8.9 (7.0–11.7) | 7.9 (6.7–9.5) | <0.001 | 9.1 (7.3–11.2) | 8.2 (6.9–10.1) | 0.003 | 0.72 |

| NTproBNP (ng/l) | 980 (340–3728) | 102 (50–341) | <0.001 | 1012 (307–5027) | 180 (99–627) | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| eGFR (ml/min) | 45± (12) | 116± (37) | – | 46 (10) | 105± (42) | – | – |

| Procedural characteristics | |||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 123± (32) | 128± (27) | 0.11 | 135± (35) | 136± (30) | 0.59 | 0.006 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 80± (21) | 77± (17) | 0.21 | 79± (20) | 79± (19) | 0.79 | 0.92 |

| Shock | 14 (11.4%) | 37 (2.9%) | <0.001 | 10 (7.3%) | 15 (3.6%) | 0.074 | 0.26 |

| Anterior myocardial infarction | 58 (47%) | 502 (39%) | 0.17 | 49 (36%) | 172 (41%) | 0.26 | 0.06 |

| Time to treatment (min) | 223 (153–321) | 179 (125–269) | 0.013 | 201 (132–338) | 188 (141–276) | 0.49 | 0.07 |

Data are presented as absolute n (%), mean± (SD) or median (IQR).

p Value for differences in characteristics between male and female patients with eGFR <60 ml/min.

CRP, C reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

Women were older and had a higher prevalence of risk factors. Generally, the biomarkers were more deviant in women.

Regarding renal function in male patients, 91.2% had an eGFR ≥60, 4.9% of 45–69 and 3.9% of <45 ml/min. In female patients, these percentages were, respectively, 75.3%, 14.9% and 9.9% (p<0.001 for the comparison between male and female patients).

Outcomes

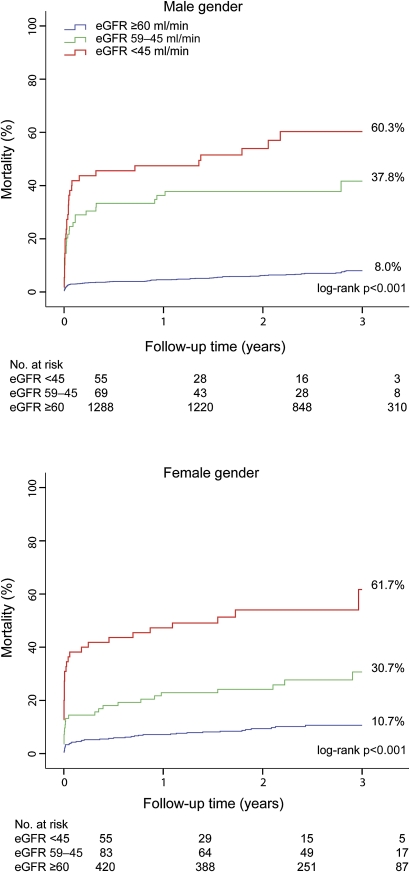

No patients were lost to follow-up. At 3-year follow-up, 240 of the 1970 patients died (cumulative mortality 13.7%). Although there was a significant difference in mortality according to gender (11.7% in men vs 18.8% in women, HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.76, p<0.001), this difference was not significant after adjustment for age (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.17, p=0.42). A decreasing renal function was associated with increasing 3-year mortality in both male and female patients (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Long-term mortality according to gender and renal function. The upper panel shows the Kaplan–Meier curves in male patients and the lower panel in female patients. p Value by the log-rank test for overall comparison.

As shown by the Cox proportional hazards models in table 2, an eGFR of <60 ml/min was associated with higher unadjusted 30-day and long-term mortality in both genders (p<0.001 for all).

Table 2.

Prognostic value of reduced admission eGFR for 30-day and long-term mortality according to gender

| Variable | Mortality |

|||||

| Male HR (95% CI) | p Value |

Female HR (95% CI) | p Value | P for interaction | ||

| Thirty-day mortality | ||||||

| Univariable | ||||||

| eGFR <60 ml/min | 12.6 (8.10 to 19.7) | <0.001 | 6.27 (3.53 to 11.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable | ||||||

| eGFR <60 ml/min | 13.59 (5.67 to 32.61) | <0.001 | 6.42 (1.89 to 21.9) | 0.003 | ||

| Age | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.04) | 0.90 | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07) | <0.01 | ||

| Multivariable* | ||||||

| eGFR <60 ml/min | 11.58 (5.39 to 24.91) | <0.001 | 3.41 (1.38 to 8.44) | 0.008 | 0.005 | |

| Multivariable* | ||||||

| eGFR 45–60 ml/min | 7.29 (2.84 to 18.72) | <0.001 | 2.39 (0.86 to 6.61) | 0.095 | ||

| eGFR <45 ml/min | 16.11 (7.17 to 36.21) | <0.001 | 7.82 (2.64 to 23.17) | <0.001 | ||

| Long-term mortality | ||||||

| Univariable | ||||||

| eGFR <60 ml/min | 9.39 (6.73 to 13.10) | <0.001 | 4.74 (3.15 to 7.13) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable | ||||||

| eGFR <60 ml/min | 5.09 (3.38 to 7.69) | <0.001 | 2.54 (1.56 to 4.13) | <0.001 | ||

| Age | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.07) | <0.001 | ||

| Multivariable* | ||||||

| eGFR <60 ml/min | 6.31 (3.74 to 10.63) | <0.001 | 2.22 (1.25 to 3.94) | 0.006 | 0.03 | |

| Multivariable* | ||||||

| eGFR 45–60 ml/min | 3.58 (1.79 to 7.14) | <0.001 | 1.65 (0.86 to 3.15) | 0.131 | ||

| eGFR <45 ml/min | 5.73 (2.68 to 12.27) | <0.001 | 4.15 (2.04 to 8.43) | <0.001 | ||

For all Cox models. The reference category for the eGFR variable is eGFR ≥60 ml/min.

Adjusted for age, body mass index, history of diabetes or hypertension systolic blood pressure and pulse, anterior myocardial infarction and time to treatment.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

An eGFR <60 ml/min remained a strong independent predictor for short- and long-term mortality irrespective of patient gender after adjustments for age or established predictors for mortality (p<0.01 for all). Importantly, the interaction term between gender and renal function was significant because overall higher mortality hazards were observed in male patients compared with female patients.

Furthermore, renal dysfunction remained associated with increased mortality (HR 5.82, 95% CI 2.91 to 11.66, p<0.001) in male patients after addition of the additional biomarkers NT-proBNP and glucose. In women, a weakened HR was observed for renal dysfunction, most likely due to lack of power (HR 1.22, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.65, p=0.61). After addition of shock to the established risk factors, the HRs were, respectively, 7.05 (95% CI 3.84 to 12.96, p<0.001) in male and 1.48 (95% CI 0.78 to 2.81, p=0.23) in female patients.

Discussion

In accordance with multiple observational and randomised trials, we observed an independent graded effect of renal insufficiency on the risk of all-cause mortality.10–12 This relationship was strong for both genders, although we noted a significant quantitative but not qualitative interaction between the genders. After multivariable risk adjustments, male patients with an eGFR below 60 ml/min were at the highest risk for mortality.

Quantitative gender difference in prognostic value eGFR

In multivariable adjustments, a significant quantitative interaction was observed between gender and renal function with regard to prognostic value for mortality. An explanation for this interaction may be found in gender differences in the prevalence of factors mechanistically linking renal dysfunction with mortality. Such factors include age, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease.13 Male patients with renal dysfunction were younger but had a higher incidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) or revascularisation compared with female patients. However, adjustment for these factors did not materially alter the HRs of the shown multivariable models. Other factors associated with both renal dysfunction and mortality did not significantly differ between men and women with renal dysfunction.

A second explanation for the gender difference in prognostic value of renal dysfunction could be that there were differences in concomitant therapy. Therapeutic nihilism has been suggested as a possible mechanism for worse outcomes with renal dysfunction.1 However, we did not observe differences in PPCI incidence, stent use or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use. Furthermore, we previously described a comparable quality of care in male and female patients.14

Renal dysfunction is associated with anaemia, endothelial dysfunction, increased homocysteine levels, procoagulant coagulopathy, systemic inflammation, hyperparathyroidism with associated disorder in calcium–phosphate homeostasis and increased risk of contrast-induced nephropathy, all of which potentially deteriorate atherosclerosis or outcomes.1 13 15 Some of these factors were not measured in our database; therefore, we cannot rule out important differences between the sexes in these factors. Therefore, residual unobserved confounding may have contributed to the differences between male and female patients.

Finally, the quantitative difference might be a spurious finding as indicated by the broad CIs.

Previous studies

The observation that eGFR is an independent risk factor for both male and female patients is in contrast to the recently published Swedish single-centre study. In this study, no prognostic value of eGFR was observed in male patients.3 In 247 STEMI patients, the unadjusted ORs for each 10 ml/min increment in eGFR for 1-year mortality in female and male patients with renal dysfunction were 0.37 and 1.05, respectively. After multivariable adjustment, the HR remained unaltered and statistically significant in women. In contrast, the adjusted OR for male patients with renal dysfunction was 1.10. It is unlikely that this difference has arisen from differences in baseline descriptors and procedural characteristics between the Swedish cohort and our cohort, as these are small. One notable exception might be the higher percentage of female patients with renal dysfunction in the Swedish study population. In our estimation, in view of the lack of a biological rationale for the difference, the most important explanation for the difference between the two studies could be the number of patients. We observed a significant difference in mortality between patients with eGFR >60 ml/min and patients with 45–59 ml/min, while the cumulative mortality curves for these groups were almost superimposable in the Swedish cohort probably due to lack of power. Other possible explanations might be that the male patients with an eGFR >60 ml/min generally had a more favourable baseline risk profile compared with the female patients with an eGFR >60 ml/min.

Finally, in the Swedish study, the eGFR was estimated with the modification of diet in renal disease equation. We estimated the eGFR with the Cockcroft and Gault formula. However, if we assume that all patients are non-black and calculate the eGFR with the modification of diet in renal disease equation, results are consistent.

In concordance with the Swedish study, a second study showed a stronger association between renal dysfunction and outcomes in female patients, although renal dysfunction had prognostic significance in both sexes.2 However, this study was performed in patients undergoing coronary angiography regardless of indication. This hampers direct comparison because mortality is higher in STEMI patients than in stable coronary artery disease patients.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current analysis have to be addressed. First, this study was performed using data from a large single-centre registry. This could be a potential source for selection bias. However, the data concerns a large heterogeneous group of STEMI patients treated by PPCI in a high-volume tertiary referral centre with surgical backup. Second, information on vital status was obtained from the Dutch national population registry, wherein information on the cause of death is not available.

Conclusions

In our large single-centre registry of STEMI patients undergoing PPCI, renal dysfunction as assessed by eGFR had prognostic significance for mortality in both male and female patients. This emphasises the role of renal function as both a prognostic marker as well as a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of atherosclerotic disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all interventional cardiologists and catheterisation laboratory nurses for the data collection.

Footnotes

To cite: Damman P, Kikkert WJ, Woudstra P, et al. Gender difference in the prognostic value of estimated glomerular filtration rate at admission in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000322. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000322

Contributors: The first two authors contributed equally. PD, WK and PW contributed to the design, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published. WK, MG and RH contributed to the interpretation of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. JB, MV, JH, JJP, JvS, JF, JGPT and RdW contributed to the collection and interpretation of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethical review committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Anavekar NS, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al. Relation between renal dysfunction and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1285–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen R, Kumar S, Timmis A, et al. Comparison of the relation between renal impairment, angiographic coronary artery disease, and long-term mortality in women versus men. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:630–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sederholm Lawesson S, Todt T, Alfredsson J, et al. Gender difference in prevalence and prognostic impact of renal insufficiency in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart 2011;97:308–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976;16:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function–measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2473–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrow DA, Antman EM, Charlesworth A, et al. TIMI risk score for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a convenient, bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation: an intravenous nPA for treatment of infarcting myocardium early II trial substudy. Circulation 2000;102:2031–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, et al. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation 2004;109:1223–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damman P, Beijk MA, Kuijt WJ, et al. Multiple biomarkers at admission significantly improve the prediction of mortality in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawesson SS, Stenestrand U, Lagerqvist B, et al. Gender perspective on risk factors, coronary lesions and long-term outcome in young patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart 2010;96:453–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medi C, Montalescot G, Budaj A, et al. Reperfusion in patients with renal dysfunction after presentation with ST-segment elevation or left bundle branch block: GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009;2:26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadeghi HM, Stone GW, Grines CL, et al. Impact of renal insufficiency in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2003;108:2769–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson CM, Pinto DS, Murphy SA, et al. Association of creatinine and creatinine clearance on presentation in acute myocardial infarction with subsequent mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1535–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luft FC. Renal disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Basic Res Cardiol 2000;95(Suppl 1):I72–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sjauw KD, Stegenga NK, Engström AE, et al. The influence of gender on short- and long-term outcome after primary PCI and delivered medical care for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. EuroIntervention 2010;5:780–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:1393–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.