Abstract

Objectives

An estimated 6%–10% of US adults took a hypnotic drug for poor sleep in 2010. This study extends previous reports associating hypnotics with excess mortality.

Setting

A large integrated health system in the USA.

Design

Longitudinal electronic medical records were extracted for a one-to-two matched cohort survival analysis.

Subjects

Subjects (mean age 54 years) were 10 529 patients who received hypnotic prescriptions and 23 676 matched controls with no hypnotic prescriptions, followed for an average of 2.5 years between January 2002 and January 2007.

Main outcome measures

Data were adjusted for age, gender, smoking, body mass index, ethnicity, marital status, alcohol use and prior cancer. Hazard ratios (HRs) for death were computed from Cox proportional hazards models controlled for risk factors and using up to 116 strata, which exactly matched cases and controls by 12 classes of comorbidity.

Results

As predicted, patients prescribed any hypnotic had substantially elevated hazards of dying compared to those prescribed no hypnotics. For groups prescribed 0.4–18, 18–132 and >132 doses/year, HRs (95% CIs) were 3.60 (2.92 to 4.44), 4.43 (3.67 to 5.36) and 5.32 (4.50 to 6.30), respectively, demonstrating a dose–response association. HRs were elevated in separate analyses for several common hypnotics, including zolpidem, temazepam, eszopiclone, zaleplon, other benzodiazepines, barbiturates and sedative antihistamines. Hypnotic use in the upper third was associated with a significant elevation of incident cancer; HR=1.35 (95% CI 1.18 to 1.55). Results were robust within groups suffering each comorbidity, indicating that the death and cancer hazards associated with hypnotic drugs were not attributable to pre-existing disease.

Conclusions

Receiving hypnotic prescriptions was associated with greater than threefold increased hazards of death even when prescribed <18 pills/year. This association held in separate analyses for several commonly used hypnotics and for newer shorter-acting drugs. Control of selective prescription of hypnotics for patients in poor health did not explain the observed excess mortality.

Article summary

Article focus

Estimate the mortality risks associated with specific currently popular hypnotics in a matched cohort design, using proportional hazards regression models.

Estimate the cancer risks associated with specific currently popular hypnotics.

Explore what risk associated with hypnotics can be attributed to confounders and comorbidity.

Key messages

Patients receiving prescriptions for zolpidem, temazepam and other hypnotics suffered over four times the mortality as the matched hypnotic-free control patients.

Even patients prescribed fewer than 18 hypnotic doses per year experienced increased mortality, with greater mortality associated with greater dosage prescribed.

Among patients prescribed hypnotics, cancer incidence was increased for several specific types of cancer, with an overall cancer increase of 35% among those prescribed high doses.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Design strengths included matching patient and control cohorts by age, gender and smoking. Through stratified statistical analyses, patients using hypnotics were matched with controls diagnosed with the exactly the same combination of 12 categories of comorbidity in up to 116 strata.

The major limitation was that residual confounding could not be fully excluded, due to possible biases affecting which patients were prescribed hypnotics and due to possible imbalances in surveillance.

Cohort studies demonstrating association do not necessarily imply causality, but the preferable randomised controlled trial method for assessing hypnotic risks may be impractical due to ethical and funding limitations.

Introduction

Hypnotic drugs are among the most widely used treatments in adult medicine. We estimate that approximately 6%–10% of US adults used these drugs in 2010, and the percentages may be higher in parts of Europe.1 2 By 1979, the Cancer Prevention Study I of the American Cancer Society had found that both cigarette smoking and hypnotic consumption were associated with excessive deaths,3 4 but the hypnotic findings were discounted since the Cancer Prevention Study I was not designed primarily to study these drugs.

At least 24 published studies have now examined mortality associated with hypnotic consumption (supplemental table 1). Of the 24 cited, 18 reported significant (p<0.05) associations of hypnotic usage with increased mortality. Lack of uniformity of measured elements makes it impossible to incorporate the majority of these studies into a meta-analysis. Nevertheless, of 22 reports from which a risk or hazard ratio (HR) for hypnotic-associated deaths could be estimated, 21 observed a risk exceeding 1.0 (p<0.001). One study observed a RR of 1.0 associating total mortality with hypnotics but found hypnotic use significantly associated with cancer mortality.5 Three other studies have reported an association of hypnotics with cancer deaths.6–8 These studies generally failed to report the specific hypnotic drugs used by the participants, often confounded hypnotics with tranquilisers not marketed for treatment of insomnia, and usually omitted monitoring of the quantities of hypnotic drugs provided participants during the follow-up intervals. Moreover, previous studies had insufficient data on the short-acting benzodiazepine agonists such as zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone that now dominate the US market because their shorter duration of action is believed to provide improved safety.

Using data from longitudinal electronic medical records maintained by a large integrated US health system, the authors planned a matched cohort study to contrast mortality and cancer associations of zolpidem and other new short-acting hypnotics with controls and with older hypnotics.

Methods

This study was conducted in the population served by the Geisinger Health System (GHS), the largest rural integrated health system in the USA. GHS serves a 41 county area of Pennsylvania with approximately 2.5 million people. The population is mostly of low socio-economic status, having less than high school education and less than one-third are insured under the Geisinger Health Plan. During the study period, the Geisinger Clinic provided primary care to approximately 250 000 unique outpatients annually, whose average duration of care in the system exceeds 10 years. Geisinger implemented an electronic health record (EHR) in 1996; it has been the sole-source ambulatory record since 2001. All outpatient encounters and related prescriptions are captured in the EHR, and Geisinger's implementation requires that both these elements be linked to an ICD-9 diagnosis code. Mortality ascertainment is updated monthly using the Social Security Death Index, thought to be accurate, but reliable cause-of-death data are not available.

Using a query into the EHR, we selected all 224 757 primary care patients ≥18 years of age with outpatient visits between 1 January 2002 and 30 September 2006. A further query of this subset identified 12 465 unique patients who had at least one order for a hypnotic medication and were followed-up and survived ≥3 months subsequent to that order. For each hypnotic user, we attempted to identify two controls with no record of a hypnotic prescription in the EHR at any time from among the 212 292 remaining non-users. Non-user controls were matched to the user cohort by: sex, age ±5 years, smoking status and start of period of observation either by calendar date ±1 year (preferred) or by length of observation. A control likewise could not have <3 months of observation in the EHR. We identified 24 793 controls, there being fewer than 200 hypnotic users for whom only one control could be matched. We extracted demographic data, height and weight measurements, diagnoses recorded in outpatient visit records, problem lists and the cancer registry, and orders for all medications, including the indication associated with that order. Only hypnotics frequently prescribed in the EHR and FDA-indicated by the US Food and Drug Administration for insomnia were included in these analyses and then only if it appeared that bedtime dosage was intended (see supplemental files). Roughly three of four (76.3%) of prescribed hypnotics had an explicitly sleep-related indication since physicians often use another diagnosis when they believe that insomnia is secondary to other conditions.9 Medication orders were further reviewed by a physician (DFK) to exclude initially identified patients who did not fully meet criteria for users and matched non-users of hypnotics. Two per cent of patients were excluded for these reasons. Patients diagnosed with major cancer (apart from non-melanoma skin cancers) before the period of observation or within the first 0.05 years of follow-up were also excluded, reducing the numbers to 10 531 users and 23 674 matched non-user controls.

As prospectively planned, we examined the associations of hypnotic prescriptions with deaths, using Cox proportional hazards models in SPSS V.12.0.0 (SPSS, Inc.). Backwards stepwise models were calculated, with likelihood ratio criteria of p<0.10 to retain a variable and p<0.05 to re-enter. To control for potential confounders, model covariates included age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, body mass index (BMI) and self-reported alcohol use and smoking status. To minimise confounding by indication (eg, a physician might have prescribed a hypnotic to treat a non-sleep condition associated with disturbed sleep), comorbid diagnoses were entered as strata in the primary models as described in the following paragraph, and other models were constructed limited to users and controls with specific categories of comorbidity. To address the possibility that hypnotics were prescribed for an emerging condition that was not yet recorded as a diagnosis, comorbid conditions were controlled whether first diagnosed before or during the period of observation.

To control for different classes of comorbidity and each patient's overall burden of comorbidities, the primary proportional hazards models were constructed incorporating stratification on up to 116 comorbidity combinations. The 116 strata compared almost all hypnotic users with non-users having exactly the same combinations of 12 classes of comorbidity. Two sets of additional models were constructed for confirmation of effects. One used strata constructed using the numbers of comorbidities comparing hazards in hypnotic users and non-users with equivalent numbers of major comorbid conditions. Another set of models restricted the population in each model to users and controls having a specific class of major chronic disease. Additional methods are described in the online supplemental files.

This study followed the guidelines of the 2008 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved and overseen by the Geisinger Institutional Review Board (IRB). Secondary approval was obtained from IRBs at the Scripps Clinic and the University of California, San Diego. The data were obtained under a data use agreement between the lead authors (RDL and DFK) and the GHS. No personally identifying data were included in the data distributed to the authors, the use of which the IRBs approved without patient consent.

Results

Zolpidem was the most frequently prescribed hypnotic drug during the study interval from 2002 to 2006, and temazepam was the next most common. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study sample, including details by categories of hypnotic used. The hypnotic user and control cohorts were well matched in age, gender, period of observation and BMI, and did not differ importantly in ethnicity, marital status or smoking status.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Non-users | Any hypnotic users | Zolpidem | Temazepam | |

| N | 23 674 | 10 531 | 4338 | 2076 |

| % Female* | 62.7 | 63.9 | 64.8 | 60.0 |

| Age (years, mean±SD)* | 53.6 ±16.6 | 54.0±16.9 | 54.0±17.1 | 53.7±17.2 |

| Years of observation (mean±SD) | 2.50±1.43 | 2.49±1.39 | 2.34±1.33 | 2.51±1.37 |

| Comorbidity classes (mean ±SD)*** | 1.06±1.27 | 1.53±1.55 | 1.49±1.54 | 1.53±1.52 |

| Died during observation (% deceased)*** | 295 (1.2) | 638 (6.1) | 265 (6.1) | 143 (6.9) |

| BMI (%)*** | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 18.7 | 19.3 | 19.5 | 18.4 |

| 25–29.9 | 24.6 | 23.6 | 23.4 | 23.7 |

| 30–34.9 | 15.8 | 16.0 | 15.8 | 16.1 |

| >35 | 13.1 | 14.4 | 13.7 | 14.2 |

| Unknown | 26.8 | 25.3 | 26.3 | 26.0 |

| Marital status (%)*** | ||||

| Married | 62.7 | 56.1 | 56.6 | 57.7 |

| Divorced | 7.9 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 11.9 |

| Single | 15.1 | 14.7 | 14.3 | 13.8 |

| Separated | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| Widowed | 12.5 | 14.8 | 15.3 | 14.4 |

| Unknown | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Ethnicity (%)*** | ||||

| White | 93.5 | 97.0 | 97.2 | 96.8 |

| Asian, Black, Hispanics | 5.6 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| Native or other | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Smoking status (%)*** | ||||

| Never | 42.7 | 42.8 | 44.1 | 41.0 |

| Unknown | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| Passive | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Quit | 32.6 | 29.9 | 29.3 | 30.6 |

| Yes, now | 21.0 | 23.5 | 22.5 | 24.5 |

| Alcohol use (%)*** | ||||

| Yes | 42.0 | 38.5 | 39.4 | 37.0 |

| No | 46.3 | 51.7 | 49.7 | 53.2 |

| Unknown | 11.7 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 9.8 |

Non-users: controls with no record of hypnotic prescription. Any hypnotic users: receiving any hypnotic prescription during the period of observation. Zolpidem: users receiving prescriptions for zolpidem only. Temazepam: users receiving prescriptions for temazepam only. Years of observation: the period of observation for users and non-users in years. Comorbidity classes: the number of disease classes diagnosed both before and during the period of observation (see supplemental files for definitions of comorbidity classes). BMI (%): the percentage of the total group within the BMI range defined (kg/m2). Ethnicity (%): the percentage in each self-reported ethnicity (Asians, Blacks and Hispanics were combined because of small numbers). Alcohol use (%): a simple yes/no self-report. See supplemental table 3 for data concerning the less commonly prescribed hypnotics. * indicates p<0.05 and *** indicates p<0.001, contrasting non-users versus all hypnotic users.

BMI, body mass index.

Table 2 presents the rates of comorbidities, including incident diagnoses. These data indicated greater comorbidity among hypnotic users for each class of diagnoses, except for dementias. For most diagnoses, there was greater comorbidity among hypnotic users before the period of observation, and greater new comorbidity incidence during the period of observation (supplemental tables 4–6.)

Table 2.

Comorbid diagnoses of non-users and users of hypnotics (percentages of total group)

| Comorbidity | Non-users | Any hypnotic users | Zolpidem | Temazepam |

| Asthma*** | 6.6 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 11.3 |

| Cerebrovascular disease*** | 3.8 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 6.1 |

| Coronary heart disease*** | 9.4 | 14.5 | 14.1 | 15.8 |

| Chronic kidney disease*** | 0.9 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| COPD*** | 5.5 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 8.8 |

| Cardiovascular disease, all*** | 14.1 | 21.4 | 21.1 | 22.3 |

| Dementia | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Diabetes*** | 14.6 | 17.9 | 17.8 | 18.5 |

| Heart failure*** | 3.2 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.6 |

| Hypertension*** | 37.5 | 42.8 | 41.9 | 43.9 |

| Obesity*** | 6.7 | 10.5 | 9.6 | 10.0 |

| Reflux and peptic disease*** | 15.0 | 27.9 | 26.9 | 26.3 |

| Peripheral vascular disease*** | 2.1 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.7 |

The percentages with each class of comorbidity diagnoses are shown for non-users and users of hypnotics. Among users, specific comorbidity percentages are shown for those prescribed only zolpidem or only temazepam. Comorbidity classes are further defined in supplemental table 2.

***Indicates p<0.001, contrasting non-users versus all hypnotic users.

Associations between hypnotic use and death

Associations between hypnotic prescriptions and deaths from Cox proportional hazards models stratified by comorbidity classes are presented in table 3. Patients prescribed any hypnotic had substantially elevated hazards of dying compared to those with equivalent comorbidity who took no hypnotics. Importantly, the death hazard was evident even in the lowest tertile of use. Compared with non-users, patients prescribed 1–18 pills of any hypnotic per year had a HR for death of 3.60 (95% CI 2.92 to 4.44). HRs increased further in the second and third tertiles of estimated pills consumed at 4.43 (95% CI 3.67 to 5.36) and 5.32 (95% CI 4.50 to 6.30). For use of zolpidem, the HR in the lowest tertile (5–130 mg/year) was similar, 3.93 (95% CI 2.98 to 5.17), and not significantly different from the HR for the lowest tertile of temazepam, 3.71 (95% CI 2.55 to 5.38), with exposure to 10–240 mg/year. For any hypnotic, or for zolpidem or temazepam specifically, the hazards of death in the middle tertiles of use were four to five times higher in users compared to non-users, and the hazards in the highest tertiles were five- or sixfold greater than those in non-users, indicating dose–response relationships for zolpidem and temazepam specifically and for any hypnotic.

Table 3.

HRs for deaths and for cancers with dose–response analyses

| Hypnotic | Deaths |

Cancers |

||

| p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Any hypnotic: doses/year | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No hypnotics, N=23 676 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 0.4–18 pills/year, mean 8, N=3491 | <0.001 | 3.60 (2.92 to 4.44) | 0.086 | 0.86 (0.72 to 1.02) |

| 18–132 pills/year, mean 57, N=3548 | <0.001 | 4.43 (3.67 to 5.36) | 0.022 | 1.20 (1.03 to 1.40) |

| >132 pills/year, mean 469, N=3490 | <0.001 | 5.32 (4.50 to 6.30) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.18 to 1.55) |

| Zolpidem only: mg/year | <0.001 | 0.035 | ||

| No zolpidem or other hypnotics, N=23 671 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Zolpidem 5–130 mg/year, mean 60, N=1453 | <0.001 | 3.93 (2.98 to 5.17) | 0.095 | 0.79 (0.60 to 1.04) |

| Zolpidem 130–800 mg/year, mean 360, N=1456 | <0.001 | 4.54 (3.46 to 5.95) | 0.585 | 1.07 (0.83 to 1.39) |

| Zolpidem >800 mg/year, mean 3600, N=1427 | <0.001 | 5.69 (4.58 to 7.07) | 0.023 | 1.28 (1.03 to 1.59) |

| Temazepam only: mg/year | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| NO temazepam or other hypnotics, N=23 674 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Temazepam 1–240 mg/year, mean 98, N=798 | <0.001 | 3.71 (2.55 to 5.38) | 0.003 | 0.48 (0.30 to 0.77) |

| Temazepam 240–1640 mg/year, mean 683, N=613 | <0.001 | 4.15 (2.88 to 5.99) | 0.024 | 1.44 (1.05 to 1.98) |

| Temazepam >1640 mg/year, mean 7777, N=665 | <0.001 | 6.56 (5.03 to 8.55) | <0.001 | 1.99 (1.57 to 2.52) |

HRs associated with levels of hypnotic consumption from Cox proportional hazards survival analyses, controlled for age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, body mass index, marital status and alcohol use and stratified by diagnoses in 12 classes of comorbidity. N: number of patients in each dose group for deaths. Restrictions of stratification produced small differences in N for the cancer analyses. p: probability that HR=1 from Cox proportional hazards models. For each drug, the top p level is for the overall contrast among dosage categories (including the no medication or reference category), and the lower p values are for the significance of each HR referenced to no hypnotic use. HR: hazard ratio for death or cancer (95% CI). Models for zolpidem and temazepam excluded patients receiving other hypnotics. See the supplemental files for additional HRs.

The death HR associated with prescriptions for less commonly prescribed hypnotic drugs were likewise elevated, and the confidence limits of death hazards for each other hypnotic overlapped that for zolpidem, with the exception of eszopiclone, which was associated with higher mortality (see supplemental files).

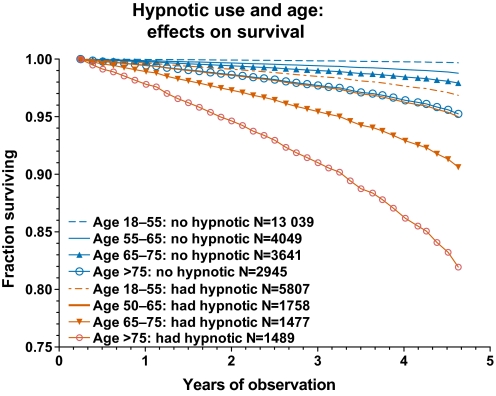

Figure 1 shows that the hazards of hypnotics were seen in every age group. Whereas the absolute magnitude of the added hazards associated with hypnotics increased with age, as did the survival risks of hypnotic-free controls, the ratio of death hazards of hypnotic users compared to non-users was greater in users aged 18–55 years than in older groups (supplemental files).

Figure 1.

Survival curves for patients prescribed no hypnotic are compared with survival curves for patients prescribed hypnotics, divided into four age groups (age at commencement of period of observation). These curves were derived from a special Cox proportional hazards model in which those taking and not taking hypnotics in the four age groups were coded as eight categories of an independent predictor variable. The curves represent the fraction of patients surviving over the increasing years of observation until censored (died, lost to follow-up or end of observation). Those censored <0.23 year of observation were excluded. The red curves represent the fact that a higher percentage of hypnotic users died during the observation periods and fewer survived. Each curve was adjusted for covariates except age (which shared excessive colinearity with the age-based categories) and was adjusted for comorbidity strata.

Models addressing potential confounding of mortality association by health status

To further address the possibility that hypnotic-associated hazards were due to use of hypnotic drugs by patients with a greater burden of disease, so that elevated risks of death might be attributable to comorbidities rather than to hypnotic medications, we conducted analyses within subgroups of hypnotic non-users and users defined by diagnoses in specific disease classes (supplemental table 7). Allowing for differences in sample size, hazards in subgroups restricted to patients with specific diseases were generally consistent with the overall findings. We also observed no statistically reliable differences in death HR in subgroups constructed to assess the overall burden of disease by stratifying on the total number of comorbidities diagnosed for each patient, and no reliable differences in death HR comparing groups diagnosed with different numbers of comorbidity classes. Whereas the raw death rate of the user cohort was 4.86 times that of non-user controls (table 1), adjustment for all covariates (eg, age, gender, BMI, smoking) with stratification by comorbidities only reduced the overall HR to 4.56 (95% CI 3.95 to 5.26).

Associations between hypnotic use and incident major cancer

Since prior studies suggested an association between hypnotics and deaths from major cancers, we constructed Cox models for major cancer incidence (ie, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer incidence) and excluding all patients who had major cancers diagnosed before the period of observation. As shown in table 3, there were modestly increased statistically significant cancer HRs for those prescribed any hypnotic compared to non-users, with the middle and highest tertiles having cancer HRs of 1.20 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.40) and 1.35 (95% CI 1.18 to 1.55), respectively. The association with zolpidem was significant for the highest tertile. The HRs for temazepam were significant for the middle tertile and the highest tertile. The cancer HR of 1.99 (95% CI 1.75 to 2.52) for the highest tertile of temazepam was significantly greater than the corresponding HRs for zolpidem or for all hypnotics combined.

Discussion

Patients with prescriptions for hypnotics had approximately 4.6 times the hazard of dying over an average observation period of 2.5 years as compared to non-users. These findings were robust with adjustment for multiple potential confounders and consistent using multiple strategies to address confounding by health status. A dose–response effect was seen. Among users in the highest tertiles of annualised dosages, the HRs for death were 5.3, 5.7 and 6.6, respectively, for all hypnotics, zolpidem alone and temazepam alone. This top third of users were prescribed 92.8% of all the prescription doses of hypnotics (supplemental figure 2). Those in the top third were also 35% more likely to develop a new major cancer.

Perhaps the most striking finding was that an increased hazard for death was present even in the lowest tertile of hypnotic use, such that hypnotic drugs were associated with a 3.6-fold increased risk of dying for patients using <18 hypnotic pills per year. Several strategies to discover biases that could account for this hazard, even at low levels of use, revealed none. Nonetheless, some residual confounding is inevitable in our results as a consequence of factors that were inadequately assessed. However, considering the minimal impact of the major confounders for which we did control upon the HRs, we think it unlikely that confounding explains the high mortality that we found associated with hypnotics.

Multiple causal pathways by which hypnotics might lead to mortality have been demonstrated. Though the acute lethality of benzodiazepine agonists seems less than that of barbiturates, it has been demonstrated in animals given high doses of benzodiazepine agonists, especially in combination with alcohol. Moreover, benzodiazepines and agonists are often present in mixed-drug overdoses.10 11 Compilation of randomised controlled trials has shown that hypnotics increase incident depression.12 Several non-randomised studies have reported an increase in suicide associated with hypnotics use,8 13–15 and depression may increase mortality through other mechanisms besides suicide.16 17

Controlled trials show that hypnotics impair motor and cognitive skills, such as driving.18 Hypnotics have been associated with increased automobile crashes and an increase in falls, due to hangover sedation.19–22 In some patients, hypnotics increase sleep apnoea, prolong apnoeas or suppress respiratory drive, though among other patients, there may be mild improvement.23–25 Sleep apnoeas, in turn, may lead to motor vehicle crashes, hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmias, cardiovascular diseases and death.26 Hypnotics may cause somnambulistic night-eating syndromes resulting in poor diet and obesity27 as well as other automaton-like behaviours, which can be dangerous.28 29 Indeed, in controlled trials, participants randomised to hypnotics experience more adverse medical events overall than those randomised to placebo.21 30

Zolpidem has been shown to increase gastroesophageal regurgitation.31 In our sample, hypnotic prescriptions were associated with increased diagnoses of oesophageal regurgitation and peptic ulcer disease (supplemental files). Increased regurgitation could cause oesophageal damage and cancer. In randomised controlled trials, patients receiving hypnotics reported significantly more infections.32 Joya et al32 inferred that increased upper respiratory irritation and infection might result from the increased gastroesophageal regurgitation caused by hypnotics. Infections, in turn, are major causes of mortality and cancer.33

Sparse data from randomised controlled trials of hypnotics suggested increased rates of cancer,34 and those findings are supported by studies demonstrating carcinogenic effects of hypnotics in laboratory rodents and by evidence that hypnotics can cause chromosomal damage.34 Our finding that for lymphomas, lung, colon and prostate cancers, the HR for hypnotic usage was even greater than the HR for current smoking (supplemental table 11) argues for specific biologic mechanisms. It is possible that patients receiving hypnotics experienced more medical care than non-users, providing greater surveillance and potential cancer detection as contrasted to non-users, even though the Cox models matched users and non-users by numbers of comorbidities. However, it would be hard to imagine how greater surveillance of hypnotic users could explain two- to threefold higher HR for some cancers with no excess mortality for other cancers (see supplemental table 11), whereas specific biological effects of hypnotics would more plausibly explain the differences in HR between cancers.

In addition to the residual confounding discussed above, the data available for this study had further limitations, which should be noted. Importantly, the EHR provided information on medication orders but not on dispensing. Accordingly, we were unable to verify that the medications ordered were dispensed by a pharmacy, and, if dispensed, whether the patient ingested the prescribed hypnotic. Moreover, controls not receiving hypnotic prescriptions might have taken hypnotics prescribed for others or over-the-counter antihistamine sleep drugs equivalent to prescribed antihistamines. Such errors of overestimation of hypnotic consumption among users or underestimation among controls would lead to underestimation of the true hypnotic hazards.

We were unable to control for depression, anxiety and other emotional factors because of Pennsylvania laws protecting the confidentiality of these diagnoses. However, several previous studies reporting hypnotic risks have controlled for these confounders.7 35 Mallon et al found that when depression, hypnotic use and other risk factors were entered into a multivariate model for all-cause mortality, hypnotic use was the strongest risk factor among men (stronger than cigarette smoking). In that analysis, depression was not an independent risk factor for death in either men or women.7 Moreover, one might expect an emotional confounder to cause insomnia, leading, in turn, to use of hypnotics, but several large studies have reported that insomnia is not a significant mortality risk factor, especially when hypnotic usage is controlled.7 35–37 Nevertheless, to the extent that social and psychological problems lead patients to receive hypnotics, and to the extent that these problems cause death through pathways independent of hypnotics, our findings might reflect some confounding by those conditions.

Conclusions

Rough order-of-magnitude estimates at the end of the supplemental files suggest that in 2010, hypnotics may have been associated with 320 000 to 507 000 excess deaths in the USA alone. From this non-randomised study, we cannot be certain what portion of the mortality associated with hypnotics may have been attributable to these drugs, but the consistency of our estimates across a spectrum of health and disease suggests that the mortality effect of hypnotics was substantial. Even 10 000 yearly excess deaths caused by hypnotics would be too many.

A randomised clinical trial of sufficient duration and size could provide definitive evidence for or against the disturbing mortality hazards suggested by our study. Some American NIH reviewers have opined that a randomised trial of hypnotic lethality would be unethical. No such trial has ever been mounted, perhaps for reasons similar to the absence of randomised trials of cigarettes and of skydiving without parachutes.38 Absent randomised trials of sufficient dimensions, we must be guided by observational data for hypnotics, as we have been guided by similar data for cigarettes.

Excess mortality is associated with hypnotic use. Hypnotic users had more prevalent disease of many sorts than non-users before hypnotics were ordered. However, the consistent results across varying levels of comorbidity and the persistent elevated hazards within strata of users and non-users matched for comorbid diagnoses strongly suggest that neither the level of individual health nor the presence of particular categories of comorbidity explains the bulk of the hazard associated with the use of hypnotic medications.

The meagre benefits of hypnotics, as critically reviewed by groups without financial interest,21 30 39 would not justify substantial risks. A consensus is developing that cognitive-behavioural therapy of chronic insomnia may be more successful than hypnotics.40 41 Against meagre benefits, it is prudent to weigh the evidence of mortality risks from the current study and 24 previous reports, in order to reconsider whether even short-term use of hypnotics, as given qualified approval in National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidance,39 is sufficiently safe.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the following staff at the Geisinger Center for Health Research: Jennifer Sartorius for help in assembling the research data set and Mary Ann Blosky for coordinating administrative issues. James Koziol, Ph.D., Professor at the Scripps Research Institute provided paid statistical consultation. Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, M.D., Professor of Family and Preventive Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, kindly reviewed and offered suggestions for the manuscript. Geisinger Center for Health Research costs were reimbersed by support from Scripps Clinic Academic Funds.

Footnotes

To cite: Kripke DF, Langer RD, Kline LE. Hypnotics' association with mortality or cancer: a matched cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000850. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000850

Contributors: DFK contributed to study concept and design, performed statistical analyses and drafted and revised the manuscript. RDL contributed to study concept and design, supervised the queries of electronic records, transformed the data files, performed statistical analyses and revised the manuscript. LEK obtained funding and administrative support, contributed public health perspectives and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript. DFK is the guarantor of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form. DFK reports long-term criticism of hypnotic drugs at his non-profit web site. DFK reports a family interest in an investment corporation, which has a small percentage of its assets in stock of Sanofi-Aventis and Johnson & Johnson. RDL and LEK report no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.International Narcotics Control Board Psychotropic Substances: Statistics for 2008; Assessments of Annual Medical and Scientific Requirements for Substances in Schedules II, III and IV of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971. New York: United Nations, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen A. Dawn of a new sleep drug? Wall St J 2011:D1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond EC. Smoking in relation to the death rates of one million men and women. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1966;19:127–204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kripke DF, Simons RN, Garfinkel L, et al. Short and long sleep and sleeping pills: is increased mortality associated? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36:103–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merlo J, Hedblad B, Ogren M, et al. Increased risk of ischaemic heart disease mortality in elderly men using anxiolytics-hypnotics and analgesics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1996;49:261–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Wingard DL, et al. Mortality hazard associated with prescription hypnotics. Biol Psychiatry 1998;43:687–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J. Is usage of hypnotics associated with mortality? Sleep Med 2009;10:279–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belleville G. Mortality hazard associated with anxiolytic and hypnotic drug use in the national population health survey. Can J Psychiatry 2010;55:137–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCall WV, Fleischer AB, Jr, Feldman SR. Diagnostic codes associated with hypnotic medications during outpatient physician-patient encounters in the United States from 1990-1998. Sleep 2002;25:221–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zosel A, Osterberg EC, Mycyk MB. Zolpidem misuse with other medications or alcohol frequently results in intensive care unit admission. Am J Ther 2011;18:305–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, et al. 2008 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 26th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47:911–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kripke DF. Greater incidence of depression with hypnotics than with placebo. BMC Psychiatry 2007;7:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allgulander C, Ljungberg L, Fisher LD. Long-term prognosis in addiction on sedative and hypnotic drugs analyzed with the Cox regression model. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1987;75:521–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlsten A, Waern M. Are sedatives and hypnotics associated with increased suicide risk in the elderly? BMC Geriatr 2009;9:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rod NH, Vahtera J, Westerlund H, et al. Sleep disturbances and cause-specific mortality: results from the GAZEL cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2010;173:300–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J. Relationship between insomnia, depression, and mortality: a 12-year follow-up of older adults in the community. Int Psychogeriatr 2000;12:295–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuijpers P, Smit F. Excess mortality in depression: a meta-analysis of community studies. J Affect Disord 2002;72:227–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermeeren A, Coenen AM. Effects of the use of hypnotics on cognition. Prog Brain Res 2011;190:89–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1701–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang PS, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ, et al. Zolpidem use and hip fractures in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1685–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, et al. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ 2005;331:1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustavsen I, Bramness JG, Skurtveit S, et al. Road traffic accident risk related to prescriptions of the hypnotics zopiclone, zolpidem, flunitrazepam and nitrazepam. Sleep Med 2008;9:18–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cirignotta F, Mondini S, Zucconi M, et al. Zolpidem-polysomnographic study of the effect of a new hypnotic drug in sleep apnea syndrome. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1988;29:807–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guilleminault C. Benzodiazepines, breathing, and sleep. Am J Med 1990;88:25S–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckert DJ, Owens RL, Kehlmann GB, et al. Eszopiclone increases the respiratory arousal threshold and lowers the apnea/hypopnea index in obstructive sleep apnea patients with low arousal threshold. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;120:505–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jean-Louis G, Brown CD, Zizi F, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk reduction with sleep apnea treatment. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2010;8:995–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgenthaler TI, Silber MH. Amnestic sleep-related eating disorder associated with zolpidem. Sleep Med 2002;3:323–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolder CR, Nelson MH. Hypnosedative-induced complex behaviours: incidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs 2008; 22:1021–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai JH, Yang P, Chen CC, et al. Zolpidem-induced amnesia and somnambulism: rare occurrences? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2009;19:74–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C, et al. The efficacy and safety of drug treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a meta-analysis of RCTs. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1335–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gagliardi GS, Shah AP, Goldstein M, et al. Effect of zolpidem on the sleep arousal response to nocturnal esophageal acid exposure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:948–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joya FL, Kripke DF, Loving RT, et al. Meta-analyses of hypnotics and infections: eszopiclone, ramelteon, zaleplon, and zolpidem. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5:377–83 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 2006;118:3030–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kripke DF. Possibility that certain hypnotics might cause cancer in skin. J Sleep Res 2008;7:245–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Althuis MD, Fredman L, Langenberg PW, et al. The relationship between insomnia and mortality among community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:1270–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, et al. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:131–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips B, Mannino DM. Does insomnia kill? Sleep 2005;28:965–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2003;327:1459–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Guidance of the use of zaleplon, zolpidem and zopiclone for the short-term management of insomnia. Technol Appraisal 2004;77:1–27 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobs GD, Pace-Schott EF, Stickgold R, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1888–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kyle SD, Morgan K, Spiegelhalder K, et al. No pain, no gain: an exploratory within-subjects mixed-methods evaluation of the patient experience of sleep restriction therapy (SRT) for insomnia. Sleep Med 2011;12:735–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.