Abstract

Objectives

To study prevalence at two time points and risk factors for experience of forced or coerced sex among school-going youth in 10 southern African countries.

Design

Cross-sectional surveys, by facilitated self-administered questionnaire, of in-school youth in 2003 and 2007.

Setting

Schools serving representative communities in eight countries (Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe) in 2003 and with Tanzania and South Africa added in 2007.

Participants

Students aged 11–16 years present in the school classes.

Main outcome measures

Experience of forced or coerced sex, perpetration of forced sex.

Results

In 2007, 19.6% (4432/25 840) of female students and 21.1% (4080/21 613) of male students aged 11–16 years reported they had experienced forced or coerced sex. Rates among 16-year-olds were 28.8% in females and 25.4% in males. Comparing the same schools in eight countries, in an analysis age standardised on the 2007 Botswana male sample, there was no significant decrease between 2003 and 2007 among females in any country and inconsistent changes among males. In multilevel analysis using generalised linear mixed model, individual-level risk factors for forced sex among female students were age over 13 years and insufficient food in the household; school-level factors were a lower proportion of students knowing about child rights and higher proportions experiencing or perpetrating forced sex; and community-level factors were a higher proportion of adults in favour of transactional sex and a higher rate of intimate partner violence. Male risk factors were similar. Some 4.7% of female students and 11.7% of male students reported they had perpetrated forced sex. Experience of forced sex was strongly associated with perpetration and other risk factors for perpetration were similar to those for victimisation.

Conclusions

Forced or coerced sex remained common among female and male youth in 2007. Experience of sexual abuse in childhood is recognised to increase the risk of HIV infection. The association the authors found between forced sex and school-level factors suggests preventive interventions in schools could help to tackle the HIV epidemic in southern Africa.

Article summary

Article focus

Cross-sectional studies 2003 and 2007.

History of coerced sex and its perpetration.

Individual, school and community risk factors.

Key messages

No evidence of decline 2003–2007.

Community factors include views of transactional sex.

School factors show clustering.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Cross-sectional study limits causal inferences.

School base excludes out of school youth.

Introduction

Sexual violence against children is a major public health problem in its own right, and it is directly and indirectly relevant to the HIV epidemic. The physical trauma of sexual violence can increase the risk of HIV transmission directly1–3 and the psychological damage related to abuse can result in increased risk-taking behaviours, re-victimisation4–7 and perpetration of sexual violence.8 9 Even for those not directly involved, having a friend or neighbour who suffers sexual abuse builds an environment where sexual violence is seen as an everyday occurrence.10 Gender violence in general (including forms other than sexual violence) is an important factor increasing the risk of HIV infection among young women in southern Africa.11

Sexual abuse of children is believed to be common in East and southern Africa but there are few quantitative studies, mostly in South Africa.12 13 Different methods of data collection and differing definitions of what is included within the term sexual violence can produce very different estimates of occurrence. A national South African study using a self-administered questionnaire reported 10% of school-going youth (both females and males) suffered forced or coerced sex each year, with around 35% affected by the age of 18 years.14 A smaller study with face-to-face questioning, also in South Africa, reported only 1.6% of girls experienced forced sex before the age of 15 years.15 A study among young women in Swaziland found that 35% of girls reported being ‘touched sexually or forced to have sex’ by the age of 18 years.16

Despite its importance as a public health problem and human rights violation, and its clear relevance to the HIV epidemic in southern Africa, there is little empirical data available on sexual violence against children in this region, especially data allowing comparisons between countries and over time. Internationally comparable surveys such as the Demographic and Health Survey do not collect information about sexual violence in this age group. Using data from nationally representative samples in eight southern African countries in 2003 and these same countries plus another two in 2007, we examined the frequency, changes over time and risk factors for experience of forced or coerced sex among school-going youth aged 11–16 years, as well as the frequency and risk factors of perpetration of forced sex in 2007. The surveys used the same instruments, training and data collection methods in the same settings on both occasions.

Methods

Sample

In 2002/2003, we drew a stratified (urban/rural) random sample of census enumeration areas (EAs) in Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe, covering 25–30 EAs in each country. The schools' sample reported here comprised the schools serving these EAs that included grades 6–9 (students aged approximately 11–17 years). In 2007, we added South Africa and Tanzania to cover a total of 259 EAs and 445 schools across the 10 countries. Within each school, the field teams randomly selected one class per grade for the survey, in grades covering students aged 11 years and above. In a few schools, at the request of the head teacher, they covered all the two to three classes per grade.

Data collection

For both surveys, we standardised training in one country and then repeated this in each country, training 25–30 field workers in each country over 1 week. The training specifically covered methods of ensuring privacy of responses in a crowded classroom, asking about sensitive issues and how to handle students who might become upset or who might have questions or seek advice because of their participation in the survey. Field coordinators approached the head teacher of each sample school and explained the survey aims. They only rarely needed to share the actual questionnaire and then only shared it with the head teacher. Head teachers of many schools chose to send information to parents about the survey (without sending details of the contents); they did not seek opt-in consent from parents for their children to participate. In each classroom, with the teacher absent, the facilitator first explained that participation was entirely voluntary and that students could leave out any questions they did not want to answer or leave the questionnaire blank. He or she then advised students to use open exercise books to ensure privacy of their responses and read each question in turn, in the language of choice of the class, encouraging participants to wait until they heard each question before writing their answer on the scannable form. Most answers required respondents to fill in one or more bubbles for response options. In each class, at least one assistant (two or more in particularly big classes) checked that the privacy arrangements were working and alerted the facilitator if any students were having difficulty with the process. The whole session, including the explanations and instructions and collection of completed response forms, took <1 hour.

The questionnaire, translated into 27 languages, asked the respondent ‘has anyone ever forced or persuaded you to have sex when you did not want to?’ We counted as suffering sexual violence those who responded positively to this closed direct question. The questionnaire used exactly the same words in 2003 and 2007. The questionnaire also asked if the respondent had ever perpetrated sexual violence (‘forced sex with someone without their consent’).

The questionnaire also documented age and sex of the respondent, whether they drank alcohol, the degree of crowding in their homes and whether there was enough food in their house in the last week (as an indicator of serious poverty).

We derived several school-level variables from 2007 data, potentially related to the risk of experience of sexual violence. Based on the youth questionnaire responses, we categorised schools as having above or below the mean (for each country) proportion of students having experienced forced or coerced sex and having perpetrated forced sex and drinking alcohol. We also documented community-level variables: whether the community was urban or rural, whether it had tar road access and whether it had any active government HIV prevention programmes. Other community-level variables came from a household survey of adults which took place in the sample EAs served by the schools in late 2002 and 2007. Trained interviewers administered a questionnaire to adults aged 16–59 years present in households, covering 24 069 respondents across the 10 countries in 2007. Other publications describe the household survey in more detail.17 18 We categorised communities as having above or below the 2007 country mean in access by good tar road; active government HIV prevention programme; proportion of adults saying that “women sometimes deserve to be beaten”; proportion of adults saying it is “okay for an older man to have sex with teenagers”; proportion of adults saying “men have the right to sex with their girlfriends if they buy them gifts” and proportion of adults reporting intimate partner violence in the last year. We also coded school-level variables as above or below the national average: proportion of students reporting experience of sexual violence; proportion of students knowing of three child rights; proportion of students agreeing that boys and girls are equal; proportion of students reporting perpetration of sexual violence and proportion of students reporting drinking alcohol.

Analysis

Operators scanned self-administered questionnaires using Remark19 and analysis relied on CIETmap open-source software.20 The analysis excluded students who did not answer the questions about sexual violence and those who did not give their age or who reported their age as ‘17 years or older’. We weighted individual country frequency estimates to account for any rural/urban disproportion in the sample compared with the population. In addition, we weighted regional frequency estimates in proportion to population of the countries; some countries were over-sampled and others under-sampled in relation to their population. To compare reported experience of forced or coerced sex between 2003 and 2007, we restricted the comparison to schools included in both surveys in eight countries, examined male and female changes separately and standardised on the age distribution of the Botswana male sample in 2007. Risk analysis of factors related to experience of forced or coerced sex reported in 2007 began by examining bivariate associations using the Mantel–Haenszel procedure.21 We adjusted these bivariate estimates of association by country and for clustering (at school level) using a method described by Lamothe22 23 based on a variance estimator to weight the Mantel–Haenszel OR for cluster-correlated data. We report the OR and cluster-adjusted CIs. Multivariate analysis of factors significant in bivariate analysis began with a saturated model, with backwards deletion excluding the weakest association, until only significant associations remained. For the multivariate analysis, we used a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) to examine personal variables like age and sex, together with household variables like crowding and food sufficiency, community-level variables like high or low prevalence of intimate partner violence and negative attitudes about gender and gender violence and school-level variables like high or low proportion of children who said they were victims or perpetrators of forced sex or drank alcohol. For GLMM, we used the R package lme4,24 achieving a fit of fixed and random effects (country) by the Laplace approximation.25

Ethical aspects

The accredited international ethical review board of CIET international approved the project in addition to an ethical review board in each country: the Health Research and Development Committee, Ministry of Health in Botswana; Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in Lesotho; the National Health Sciences Research Committee, Ministry of Health in Malawi; the Comité Nacional de Bioética para a Saude, Ministerio da Saude in Mozambique; the Research Management Committee, Ministry of Health and Social Services in Namibia; the CIET Trust Research Ethics Committee in South Africa; the Scientific and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in Swaziland; the Institutional Review Board, Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre in Tanzania; the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Health, Zambia and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe. In each country, we also received written authority from the Ministry of Education to interview children in school. School head teachers gave consent to survey students in their school and contacted parents to inform them about the survey in general terms and give them the option to opt-out their child.

Results

From 60 646 facilitated self-administered questionnaires in schools in the 10 countries in 2007, we obtained 59 986 usable records (1.1% did not complete or spoiled their questionnaires). We excluded 10 631 respondents (17.7%) who did not report their age or reported their age as ‘17 years or older’ (9623). Of 49 355 respondents aged 11–16 years, 48 586 (98.4%) answered the question about forced or coerced sex. In 2003, 28 896 students aged 11–16 years in eight of the countries completed the questionnaire and 27 772 (96.1%) of them answered the question about forced or coerced sex.

In 2007, some 27.5% (based on 13 216/47 102) of respondents lived in houses with more than three people per room and 13.6% (based on 8498/48 614) reported they had insufficient food in their households in the week before the survey. Some 29.2% (based on 14 178/49 355) correctly recognised three child rights (to go to school, to be safe and not to be abused). Based on direct observation and key informant responses, 46.4% (based on 17 202/42 028 for whom this information was available) lived in a community that could be accessed by good tar road and 67.7% (based on 30 953/44 661) lived near an active government HIV prevention programme.

Experience of forced sex

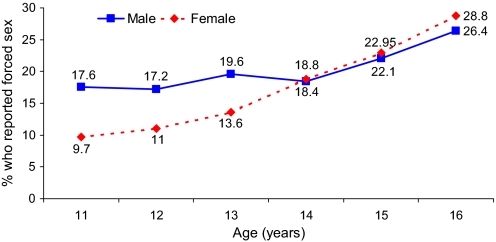

Weighting for country size and urban/rural proportions in each country, in 2007, 19.6% (based on 4432/25 840) of female youth and 21.1% (based on 4080/21 613) of male youth aged 11–16 years reported they had experienced forced or coerced sex. Figure 1 shows the age- and sex-specific rates, each point representing the population weighted average across 10 countries, for ages 11–16 years and for male and female respondents. Up until the age of 14 years, male students reported higher rates than female students. Table 1 shows the weighted percentages of male and female students aged 16 years who had ever experienced forced or coerced sex in each of the 10 countries. Across the 10 countries, 25.4% of male students and 28.8% of female students had experienced forced or coerced sex by the time they were 16. There was considerable variation between countries. Among males, the rates ranged from 11.9% in Botswana to 37.8% in Malawi, and in females, they ranged from 15.0% in Botswana to 43.2% in Tanzania.

Figure 1.

Proportions of male and female youth aged 11–16 years who reported forced or coerced sex. Each point represents the population-weighted average across the 10 countries. Female rates 11–16 years are based on 107/1064, 346/3026, 661/4986, 1039/6373, 1161/5837, 1118/4554, respectively. Male rates 11–16 years are based on 106/716, 339/2061, 692/3814, 876/5080, 974/5180, 1093/4762, respectively.

Table 1.

Reported experience of forced or coerced sex among male and female students aged 16 years in 2007, by country

| Country | Fraction (weighted %) who ever experienced forced or coerced sex |

|

| Male students | Female students | |

| Botswana | 48/408 (11.5) | 44/299 (14.7) |

| Lesotho | 127/587 (22.6) | 174/790 (21.5) |

| Malawi | 165/436 (37.8) | 87/237 (36.9) |

| Mozambique | 124/472 (27.0) | 65/290 (21.5) |

| Namibia | 80/334 (24.4) | 93/330 (29.4) |

| South Africa | 142/767 (17.7) | 176/955 (18.3) |

| Swaziland | 79/562 (13.9) | 84/496 (17.2) |

| Tanzania | 119/356 (32.0) | 196/460 (42.6) |

| Zambia | 152/572 (26.6) | 159/491 (33.4) |

| Zimbabwe | 45/219 (20.2) | 23/140 (15.7) |

| All countries combined | 1093/4762 (25.4) | 1118/4554 (28.8) |

Table 2 shows country-specific rates of the experience of forced or coerced sex in 2003 and 2007, separately for male and female respondents, age standardised on the age distribution in the Botswana 2007 male sample. The comparison is limited to those schools covered in the survey in eight countries in both 2003 and 2007. Among male respondents, age-standardised rates decreased significantly in two countries, increased significantly in two and did not change significantly in the other four. Among female respondents, in all but one country, there was a lower rate in 2007 than in 2003, but none of the changes on their own were significant.

Table 2.

Age-standardised comparison between 2003 and 2007: experience of forced or coerced sex among school-going youth aged 11–16 years, in schools which conducted both surveys

| Country | Male |

Age-standardised contrast 2007/2003, RR (95% CI) | Female |

Age-standardised contrast 2007/2003, RR (95% CI) | ||||||

| 2003 |

2007 |

2003 |

2007 |

|||||||

| Cases/total | Age-standardised rate* | Cases/total | Age-standardised rate* | Cases/total | Age-standardised rate* | Cases/total | Age-standardised rate* | |||

| Botswana | 163/1006 | 0.164 | 295/2812 | 0.0995 | 0.61 (0.49 to 0.75) | 142/1215 | 0.113 | 348/3342 | 0.099 | 0.88 (0.74 to 1.05) |

| Lesotho | 352/1917 | 0.170 | 416/2071 | 0.211 | 1.24 (1.04 to 1.49) | 451/2805 | 0.156 | 499/3269 | 0.137 | 0.88 (0.75 to 1.02) |

| Malawi | 521/1829 | 0.258 | 517/1904 | 0.246 | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.10) | 479/1822 | 0.249 | 465/1698 | 0.255 | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.17) |

| Mozambique | 233/947 | 0.268 | 479/2043 | 0.264 | 0.98 (0.69 to 1.39) | 153/698 | 0.180 | 291/1562 | 0.179 | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.28) |

| Namibia | 325/1313 | 0.234 | 332/1355 | 0.238 | 1.02 (0.84 to 1.23) | 397/1736 | 0.219 | 394/1698 | 0.209 | 0.95 (0.84 to 1.12) |

| Swaziland | 259/2024 | 0.122 | 249/2389 | 0.091 | 0.75 (0.62 to 0.90) | 360/2792 | 0.121 | 358/2948 | 0.116 | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.13) |

| Zambia | 501/1807 | 0.241 | 418/1699 | 0.236 | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.21) | 526/1837 | 0.249 | 495/2012 | 0.221 | 0.89 (0.75 to 1.03) |

| Zimbabwe | 202/1247 | 0.109 | 511/2772 | 0.183 | 1.68 (1.41 to 1.94) | 326/1577 | 0.192 | 527/3461 | 0.154 | 0.80 (0.53 to 1.20) |

Values in bold indicate a 2003–2007 difference significant at the 5% level.

Direct age standardisation on Botswana 2007 male population.

Table 3 shows the bivariate associations, adjusted for country and clustering, between personal and cluster-level variables and experience of forced or coerced sex, among male and female students. The patterns were similar among the males and females: older youth were more likely to have experienced forced or coerced sex, as were those who did not have enough food in the house in the last week. Students attending schools where experience and perpetration of forced sex was more common and where more students used alcohol were more likely to report experiencing forced or coerced sex.

Table 3.

Risk factors for lifetime experience of sexual violence in school-going male and female youth aged 11–16 years in 2007

| Characteristics | Categories | Lifetime experience of sexual violence* |

|||

| Male |

Female |

||||

| Proportions | OR (95% CI)† | Proportions | OR (95% CI)† | ||

| Individual and household variables | |||||

| Age group | 11–13 years | 1137/6591 | 1.13 (1.03 to 1.23) | 1114/9076 | 1.71 (1.52 to 1.92) |

| 14–16 years | 2943/15 022 | 3318/16 764 | |||

| Area of residence | Urban | 1685/10 007 | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.25) | 1840/12 237 | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.25) |

| Rural | 2395/11 606 | 2592/13 603 | |||

| Crowding in the house | 1–3 per room | 2710/14 840 | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.04) | 3055/17 814 | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) |

| 4–10 per room | 1154/5767 | 1206/7006 | |||

| Enough food in the house in the last week | Yes | 3199/17 621 | 1.33 (1.20 to 1.46) | 3409/21 041 | 1.51 (1.35 to 1.69) |

| No | 824/3724 | 952/4457 | |||

| Community-level variables | |||||

| Access by good tar road | Yes | 1319/7405 | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.09) | 1496/9190 | 1.03 (0.88 to 1.20) |

| No | 2260/11 190 | 2309/12 673 | |||

| Active government HIV prevention programme | Yes | 2390/13 124 | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.17) | 2524/15 361 | 1.01 (0.85 to 1.19) |

| No | 1185/5551 | 1196/6538 | |||

| Proportion of adults saying that “women sometimes deserve to be beaten” | Below average | 1979/10 366 | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.07) | 2139/12 442 | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.04) |

| Above average | 1884/10 104 | 2028/12 142 | |||

| Proportion of adults saying it is “okay for an older man to have sex with teenagers” | Below average | 2582/13 517 | 0.98 (1.86 to 1.12) | 2865/16 462 | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.03) |

| Above average | 1281/6953 | 1302/8122 | |||

| Proportion of adults saying “men have the right to sex with their girlfriends if they buy them gifts” | Below average | 2213/11 879 | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.20) | 2515/14 535 | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) |

| Above average | 1650/8591 | 1652/10 049 | |||

| Proportion of adults reporting intimate partner violence in last year | Below average | 1654/8619 | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.07) | 1785/10 435 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.15) |

| Above average | 2209/11 851 | 2385/14 149 | |||

| School-level variables | |||||

| Proportion of students reporting experience of sexual violence | Below average | 1540/10 909 | 1.94 (1.73 to 2.17) | 1819/13 561 | 1.84 (1.61 to 2.11) |

| Above average | 2540/10 704 | 2613/12 279 | |||

| Proportion of students knowing of three child rights | Above average | 1678/9588 | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.25) | 2095/12 263 | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) |

| Below average | 2402/12 025 | 2337/13 577 | |||

| Proportion of students agreeing that boys and girls are equal | Above average | 1851/10 491 | 1.13 (1.00 to 1.27) | 2255/13 342 | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) |

| Below average | 2229/11 122 | 2177/12 498 | |||

| Proportion of students reporting perpetration of sexual violence | Below average | 1939/12 293 | 1.60 (1.42 to 1.81) | 2298/15 320 | 1.48 (1.29 to 1.70) |

| Above average | 2141/9320 | 2134/10 520 | |||

| Proportion of students reporting drinking alcohol | Below average | 2182/12 700 | 1.34 (1.19 to 1.52) | 2370/14 831 | 1.31 (1.15 to 1.49) |

| Above average | 1898/8913 | 2062/11 009 | |||

Values in bold indicate associations significant at the 5% level.

Defined as those who responded positively to the question: “Has anyone ever forced or persuaded you to have sex when you did not want to?”

OR and 95% CI from bivariate analysis of group with characteristic compared with counterfactual group (eg, age 14–16 years compared with age 11–13 years), stratified by country and adjusted for clustering.

Multilevel analysis (GLMM) treated country as a random effect (table 4). The final GLMM model for female youth included one personal factor (age over 13 years), a household factor (insufficient food in the last week), three school group factors (a higher proportion who experienced forced or coerced sex, a higher proportion who perpetrated forced sex and a lower proportion who knew about child rights) and two community factors (where more adults said a man could expect sex if he gave a gift to a woman and where more adults reported intimate partner violence in the last year). Among male youth, there was one household factor (insufficient food in the last week), three school group factors (a higher proportion who experienced forced or coerced sex, a higher proportion who perpetrated forced sex and a higher proportion who reported use of alcohol) and one community factor (where more adults said a man could expect sex if he gave a gift to a woman).

Table 4.

GLMM of factors associated with forced or coerced sex in male and female youth aged 11–16 years

| Variables in final GLMM models | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

| Males (n=22 098) | Females (n=26 292) | |

| Age over 13 years | 1.49 (1.38 to 1.61) | |

| Insufficient food in the last week | 1.22 (1.12 to 1.34) | 1.40 (1.29 to 1.53) |

| Attending a school where there was a higher proportion of students who said they had suffered sexual violence | 1.79 (1.65 to 1.95) | 1.76 (1.62 to 1.90) |

| Attending a school where a lower proportion of students knew about child rights | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.25) | |

| Attending a school where there was a higher proportion of students who said they had perpetrated sexual violence | 1.22 (1.12 to 1.33) | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.28) |

| Attending a school where alcohol use was more common among students | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.20) | |

| Living in a community where a higher proportion of adults said a man could expect sex if he gave a gift to a woman | 1.16 (1.08 to 1.26) | 1.16 (1.07 to 1.24) |

| Living in a community where a higher proportion of adults reported intimate partner violence in the last year | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.17) | |

Country was treated as a random effect in the models. The initial saturated models for males and females included all the variables in table 2.

GLMM, generalised linear mixed model.

While the school group variables in table 4 each had an effect in their own right, there was also evidence that the factors combined to increase the risk of sexual violence. Of female youth at schools where fewer people reported being a victim and fewer claimed to be perpetrators, 13.2% (1460/11 030) had suffered sexual violence; of those at schools where fewer than average were victims and more were perpetrators, 14.2% (359/2531) suffered sexual violence; of those with more victims and fewer perpetrators, 19.5% (838/4290) suffered sexual violence and of those at schools with more victims and more perpetrators, 22.2% (1775/7989) suffered sexual violence.

Perpetration of forced sex

In 2007, weighted for country population and urban/rural proportions in each country, 4.7% of female students (based on 1157/25 902) and 11.7% of male students (based on 2413/21 701) said they had perpetrated forced sex. The final GLMM model of risk factors for female perpetration of forced sex (table 5) included one personal factor (experienced forced or coerced sex), four school group factors (a higher proportion of students who experienced sexual violence, a higher proportion who perpetrated sexual violence, a lower proportion who knew about child rights and a higher proportion who used alcohol) and three community factors (where more adults said it is okay for older men to have sex with teenagers, where more adults reported intimate partner violence in the last year and communities that could not be accessed by tar road). The final GLMM model of risk factors for male perpetration of forced sex (table 5) included one personal factor (experienced forced or coerced sex), a household factor (insufficient food in the last week), three school group factors (a higher proportion of students who experienced sexual violence, a higher proportion who perpetrated sexual violence and a higher proportion who used alcohol) and one community factor (communities that could not be accessed by tar road).

Table 5.

GLMM of factors associated with being a perpetrator of forced sex, among male and female youth aged 11–16 years

| Variables in final GLMM models | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

| Males (n=22 098) | Females (n=26 292) | |

| Experienced forced or coerced sex | 4.37 (3.96 to 4.82) | 5.34 (4.66 to 6.13) |

| Insufficient food in the last week in household | 1.30 (1.16 to 1.45) | |

| Attending a school where there was a higher proportion of students who said they had suffered sexual violence | 1.51 (1.28 to 1.78) | |

| Attending a school where a lower proportion of students knew about child rights | 1.29 (1.16 to 1.43) | 1.35 (1.16 to 1.57) |

| Attending a school where a higher proportion of students said they had perpetrated forced sex | 2.23 (2.01 to 2.49) | 2.13 (1.81 to 2.51) |

| Attending a school where a higher proportion of students drank alcohol | 1.25 (1.13 to 1.38) | 1.17 (1.01 to 1.36) |

| Living in a community that is not accessible by tar road | 1.33 (1.20 to 1.48) | 1.51 (1.30 to 1.75) |

| Living in a community where a higher proportion of adults said it is acceptable for an older man to have sex with a teenager | 1.17 (1.01 to 1.35) | |

| Living in a community where a higher proportion of adults reported intimate partner violence in the last year | 1.23 (1.07 to 1.42) | |

Country was treated as a random effect in the models.

GLMM, generalised linear mixed model.

Discussion

Sexual violence was very common among school children in the 10 countries of southern Africa, affecting one in every five children aged 11–16 years of both sexes. The occurrence increased with age, so that by 16 years, a quarter of male students and a higher proportion of female students said they had experienced forced or coerced sex.

There was little evidence of a reduction in rates of forced sex between 2003 and 2007; the small reduction among female students was not significant in any country and the pattern among male students was inconsistent, with decreases in some countries but increases in others.

Risk factors for female and male students were similar, including personal factors (age), household-level factors (insufficient food as an indicator of poverty), school-level factors (attending schools where sexual violence and alcohol use was more common) and community-level factors (communities with more support for transactional sex and more intimate partner violence).

One in every 10 male students and one in 20 female students in 2007 said they had perpetrated forced sex. Victimisation was a strong risk factor for perpetration in both male and female students, and again, there were school- and community-level risk factors.

The 2007 study applied the same instrument in 10 countries within a period of 4 months, generating comparable data about coerced sex among youth of these 10 countries. This is the first school-based study of sexual violence using the same instrument at the same time across multiple countries in southern Africa. The anonymous self-administered questionnaire under carefully arranged conditions may have increased disclosure compared with face-to-face interviews, and this might help to explain the higher rates of forced sex than a study in South Africa that used face-to-face interviews.15 Our measure of sexual violence was limited specifically to coerced physical sex. This leads to lower estimates of sexual violence than studies that include unwanted touching and verbal abuse as well as forced sex.16

The school-based surveys probably underestimated the rates of forced and coerced sex among all children since we excluded children not in school, who may have a higher risk of experiencing sexual violence or who may have left school because they experienced sexual violence. We have no details about enrolment and attendance other than on the day of the survey. The school-based surveys did not contact young women who were unable to attend school due to pregnancy, a possible result of sexual abuse. The percentage of female students illustrates their dropout with age: 60%, 59%, 57%, 55%, 53% and 49% with increasing age from 11 through to 16 years. If girls who experience forced or coerced sex leave school as a result, this could explain the apparently small gender gap or, in many country- and age-specific groups, more frequent reports of sexual violence among male than female respondents.

As with any self-reported experience, some students declined to answer questions and some may have given false answers. We recognise reasons not to report but we have no basis to expect respondents to fabricate a history of coerced sex; we expect this bias underestimated true rates. It is possible that under-reporting of forced or coerced sex was more marked among the female students. If so, this could explain our finding of a similar reported rate of forced sex between the sexes, even if the female youth actually experienced more forced sex.

There is a prevailing belief that child sexual abuse affects predominantly girls. Studies in Europe, the USA and Australia have generally reported higher rates of experience of sexual violence among female than male youth,26–31 although a recent study from Ireland reported male rates of experience of sexual abuse in childhood not much lower than female rates.32 Few studies from Africa report both male and female rates of experience of child sexual abuse. Collings33 reported that 29% of a small sample of male university students in South Africa had experienced contact or non-contact sexual abuse as children and later reported 35% of female students in the same university had experienced contact forms of sexual abuse as children.34 Two studies from a province of South Africa found similar rates of experience of childhood sexual violence among male and female youth35 36 and a large study of school-going youth in South Africa found similar rates of experience of forced or coerced sex among males and females.14 37 The problem is much less studied among male youth, especially in Africa, with many enquiries limited to female youth.

By definition, sex with children is abuse whether or not the child ‘consents’. The age of consent is complicated, with differing ages in different forms of legislation. The age of consent in the countries included in our study is generally 16 years and 18 years in Tanzania. Thus, nearly all coerced sex reported in our study was child sexual abuse as a matter of definition. The questionnaire asked those who reported forced or coerced sex how old they were when it first occurred. Of the 1,118 sixteen-year-old females who reported forced or coerced sex, 498 said this first occurred when they were aged 16 years or did not give an age when it occurred, similarly among the 1093 sixteen-year-old males reporting forced or coerced sex, 377 said it first occurred when they were aged 16 years or did not specify the age of first occurrence. A sensitivity analysis excluded these 875 youth; we could detect no shift in the pattern of risk factors.

The risk factors we included in the survey and analysis were based on evidence from other studies,12 26 27 33 34 38–40 and a belief that since sexual violence is a clustered phenomenon, factors at school and community level may be important. We recognise other risk factors for forced sex among children that this study did not measure.12 33 34

Our findings on perpetration of forced sex are consistent with those reported elsewhere.12 Male students were more likely to admit to forcing sex on someone else, but some female students also admitted to it. And being a victim of forced or coerced sex was a strong risk factor for being a perpetrator. In this cross-sectional study, we cannot say which came first, but the finding is compatible with the finding that many child perpetrators of rape have themselves been victims of sexual abuse.41

School-based group variables were strong risk factors for experience of forced or coerced sex and indeed perpetration of forced sex, illustrating the social nature of sexual violence. In this cross-sectional study, we cannot draw conclusions about which came first: personal experiences leading to school characteristics or the other way around. It seems plausible that some schools foster a culture of sexual violence, while others foster a culture of protection. If true, this could be key for school-based strategies to reduction of sexual violence among the students. Raghavan and colleagues42 showed that witnessing community violence influenced social support networks, and these in turn influenced gender violence. The counterpoint is that not witnessing community violence might also influence gender violence but in a positive way.

Sexual abuse in childhood is profoundly linked to the risk of HIV, largely through high-risk behaviours among survivors10; the high rates of forced and coerced sex we found among school students are a cause for serious concern. Increasing resources and developing approaches for reducing sexual abuse of children in southern Africa, including randomised controlled trials of school-based interventions, should be a public health priority.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

These findings emanate from further analysis of the “Soul City regional programme audience reception and impact evaluation”, for which CIET were commissioned to undertake surveys in eight countries in 2002–2003 and 2007. The Tanzania survey was part of the African Development of AIDS Prevention Trials capacities (ADAPT) project, funded by the Global Health Research Initiative through Canada's International Development Research Centre IDRC grant 104051-005. CIET Trust funded the South African survey. We thank the Ministries of Education that authorised the survey in the 10 countries, CIET field teams in each country and the 60 000 school-going youth who contributed to the survey.

Footnotes

To cite: Andersson N, Paredes-Solís S, Milne D, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for forced or coerced sex among school-going youth: national cross-sectional studies in 10 southern African countries in 2003 and 2007. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000754. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000754

Contributors: NA designed the studies, provided oversight and training for fieldwork, conducted the analysis and wrote the present manuscript. SPS, DM, KO, NM and DL conducted the fieldwork and contributed to the writing. AC provided training and field supervision for the 2007 study and assisted with writing of the current manuscript. NA and AC are guarantors.

Funding: The Soul City commissioned surveys were funded by the European Union. The Tanzania survey was funded by the Global Health Research Initiative through the International Development Research Centre.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Health Research and Development Committee, Ministry of Health in Botswana; Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in Lesotho; the National Health Sciences Research Committee, Ministry of Health in Malawi; the Comité Nacional de Bioética para a Saude, Ministerio da Saude in Mozambique; the Research Management Committee, Ministry of Health and Social Services in Namibia; the CIET Trust Research Ethics Committee in South Africa; the Scientific and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in Swaziland; the Institutional Review Board, Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre in Tanzania; the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Health, Zambia and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe. In each country, we also received written authority from the Ministry of Education to interview children in school.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from this study are not in the public domain.

References

- 1.Jenny C, Hooton TM, Bowers A, et al. Sexually transmitted disease in victims of rape. N Engl J Med 1990;322:713–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glaser JB, Schachter J, Benes S, et al. Sexually transmitted disease in post-pubertal female rape victims. J Infect Dis 1991;164:726–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meel BL. HIV infection among victims of sexual assault using condoms and other contraceptive methods: a comparative study. Med Sci Law 2007,47:341–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koenig MA, Zablotska I, Lutalo T, et al. Coerced first intercourse and reproductive health among adolescent women in Rakai, Uganda. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2004;30:156–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindegren ML, Hanson IC, Hammett TA, et al. Sexual abuse of children: intersection with the HIV epidemic. Pediatrics 1998;102:E46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, et al. Outcomes from a group intervention for coping with HIV/AIDS and childhood sexual abuse: reductions in traumatic stress. AIDS Behav 2007;11:49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen M, Deamant C, Barkan S, et al. Domestic violence and childhood sexual abuse in HIV-infected women and women at risk for HIV. Am J Public Health 2000;90:560–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:1603–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, Finkelhor D. Impact of sexual abuse on children: a review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychol Bull 1993;113:164–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat MD, et al. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:459–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersson N, Cockcroft A, Shea B. Gender-based violence and HIV: relevance for HIV prevention in hyperendemic countries of southern Africa. AIDS 2008;22(Suppl 4):S73–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lalor K. Child sexual abuse in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. Child Abuse Negl 2004;28:439–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lalor K. Child sexual abuse in Tanzania and Kenya. Child Abuse Negl 2004;28:833–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson N, Ho-Foster A, Matthis M, et al. National cross sectional study of views on sexual violence and risk of HIV infection and AIDS among South African school pupils. BMJ 2004;329:952–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jewkes R, Levin J, Mbananga N, et al. Rape of girls in South Africa. Lancet 2002;359:319–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reza A, Breiding MJ, Gulaid J, et al. Sexual violence and its health consequences for female children in Swaziland: a cluster survey study. Lancet 2009;373:1966–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersson N, Ho-Foster A, Mitchell S, et al. Risk factors for domestic violence: eight national cross-sectional household surveys in southern Africa. BMC Womens Health 2007;7:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell S, Cockcroft A, Andersson N. Equity in HIV testing: evidence from a cross-sectional study in ten Southern African countries. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2010;10:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.http://www.gravic.com/remark/officeomr/index.html?gclid=CJzi0-St96oCFSEEQAodIwyPGA

- 20.Andersson N, Mitchell S. Epidemiological geomatics in evaluation of mine risk education in Afghanistan: introducing population weighted raster maps. Int J Health Geogr 2006;5:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 1959;22:719–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamothe G. Adjusting the Mantel Haenszel test statistic and Odds Ratio for cluster sampling. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11(Suppl 2):S15 (Statistical annex). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersson N, Lamothe G. Clustering and meso-level variables in cross-sectional surveys: an example of food aid during the Bosnian crisis. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11(Suppl 2):S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bates D, Maechler M.http://lme4.r-forge.r-project.org/

- 25.Wolfinger R. Laplace's approximation for nonlinear mixed models. Biometrika 1993;80:791–5 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouvier P, Halpern D, Rey H, et al. Typology and correlates of sexual abuse in children and youth: multivariate analyses in a prevalence study in Geneva. Child Abuse Negl 1999;23:779–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eghardh K, Ormstad K. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual abuse in a national sample of Swedish seventeen-year-old boys and girls. Acta Paediatr 2000;88:310–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Priebe G, Svedin CG. Child sexual abuse is largely hidden from the adult society: an epidemiological study of adolescents' disclosures. Child Abuse Negl 2008;32:1095–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danielsson I, Blom H, Nilses C, et al. Gendered patterns of high violence exposure among Swedish youth. Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica 2009;88:528–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olshen E, McVeigh KH, Wunsch-Hitzig RA, et al. Dating violence, sexual assault, and suicide attempts among urban teenagers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:539–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore EE, Romaniuk H, Olsson CA, et al. The prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and adolescent unwanted sexual contact among boys and girls living in Victoria, Australia. Child Abuse Negl 2010;34:379–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGee H, Garavan R, Byrne J, et al. Secular trends in child and adult sexual violence-one decreasing and the other increasing: a population survey in Ireland. Eur J Public Health 2010;21:98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collings SJ. Childhood sexual abuse in a sample of South African university males: prevalence and risk factors. South Afr J Psychol 1991;21:153–8 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collings SJ. Child sexual abuse in a sample of South African women students: prevalence, characteristics, and long-term effects. South Afr J Psychol 1997;27:37–42 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madu SN, Peltzer K. Risk factors and child sexual abuse among secondary school students in the Northern Province (South Africa). Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:259–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Madu SN. The relationship between parental physical availability and child sexual, physical and emotional abuse: a study among a sample of university students in South Africa. Scand J Psychol 2003;44:311–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson N, Ho-Foster A. 13,915 reasons for equity in sexual offences legislation: a national school-based survey in South Africa. Int J for Equity Health 2008;7:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bassani DG, Palazzo LS, Beria JU, et al. Child sexual abuse in southern Brazil and associated factors: a population-based study. BMC Public Health 2009;9:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breiding MJ, Reza A, Gulaid J, et al. Risk factors associated with sexual violence towards girls in Swaziland. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:203–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laaksonen T, Sariola H, Johansson A, et al. Changes in the prevalence of child sexual abuse, its risk factors, and their associations as a function of age cohort in a Finnish population sample. Child Abuse Negl 2011;35:480–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantwell HB. Child sexual abuse: very young perpetrators. Child Abuse Negl 1990;14:294–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raghavan C, Rajah V, Gentile K. Community violence, social support networks, ethnic group differences, and male perpetration of intimate partner violence. J Interpersonal Violence 2009;24:1615–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.