Abstract

Objectives

To assess a 2-year family-based behavioural intervention programme against child obesity.

Design

Single-group pre- and post-intervention feasibility study.

Setting

Swedish paediatric outpatient care.

Participants

26 obese children aged 8.3–12.0 years and their parents who had consented to actively participate in a 2-year intervention.

Interventions

25 paediatric outpatient group sessions over a 2-year period with parallel groups for children and parents. The basis for the programme was a manual containing instructions for tutor-supervised group sessions with obese children and their parents.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was change in standardised body mass index between baseline and after 36 months. The secondary outcome measures were change in the waist:height ratio, metabolic parameters and programme adherence. The participants were examined at baseline and after 3, 12 and 24 months of therapy and at follow-up 12 months after completion of the programme.

Results

The primary outcome measure, standardised body mass index, declined from a mean of 3.3 (0.7 SD) at baseline to 2.9 (0.7 SD) (p<0.001) at follow-up 12 months after completion of the programme. There was no change in the waist:height ratio. Biomedical markers of blood glucose metabolism and lipid status remained in the normal range. 96% of the families completed the programme.

Conclusions

This feasibility study of a 2-year family-based behavioural intervention programme in paediatric outpatient care showed promising results with regard to further weight gain and programme adherence. These findings must be confirmed in a randomised controlled trial with longer follow-up before the intervention programme can be implemented on a larger scale.

Article summary

Article focus

Family-based behavioural interventions have produced promising results in controlled studies, but their effectiveness in paediatric outpatient settings remains to be shown.

Key messages

A 2-year family-based behavioural intervention programme for the management of childhood obesity in paediatric outpatient care showed promising results with regard to weight gain 1 year after the programme.

The completion rate of the programme was high, which is important as high family adherence is a success factor for childhood obesity therapy.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main methodological strengths of this study are that the primary end point measurement was performed 12 months after completion of the long-term intervention programme and that all participants were included in the data analysis at the study end point whether or not they had completed the intervention.

The major weaknesses of the study are the small study sample and single-group design. The design implies that the observed decline in standardised body mass index cannot be firmly interpreted as an effect of the intervention programme. The results would have been even more convincing if all the secondary outcome measures had displayed similar trends. Longer follow-up than 12 months is necessary to examine sustainable effects of the intervention.

Introduction

Child and adolescent obesity has increased globally.1−3 In the USA, childhood obesity has more than tripled for children aged 6–11 years in the past 3 decades with around 9 million obese children aged older than 6 years.4 In Sweden, obesity in 10-year-old children increased fourfold in <2 decades,5 although recent results have shown that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in childhood is levelling off.6 Childhood obesity is resulting in significant short-term2 7 and long-term2 7–9 consequences on health and well-being, and increased mortality.9 This situation calls for evidence-based child obesity management programmes, which in turn requires research, re-formulation of health policies and re-organisation in the healthcare system.10

A natural target for these efforts is the family. Almost 50 years ago, the idea of a family as a system was presented, an emotional completeness where the individuals are strongly tied to each other.11 The family system perspective visualises how the relationship with family diet, care giver resources and child character can be mediated or moderated by a variety of influences ranging from cultural characteristics and motherly input into family economic decisions and social support.12 A child's success with behaviour changes in association with obesity treatment has been found to be strongly contingent on the participation of the entire family in the process13 14 and on the treatment being initiated at an early age.15 A recent Cochrane review concluded that family-based behavioural lifestyle interventions intended to change diet and exercise patterns together with self-help can reduce weight in children in the short-term as well as in the long-term.2 Two approaches that have shown promising results for childhood obesity in specialist settings are cognitive behavioural therapy16 and family-based lifestyle intervention.17 However, implementation of cognitive behavioural therapy and treatments involving families require financial and personal resources that seldom are at hand for service supply to all families with obese children; however, present evidence suggests that it is difficult to maintain changes in children's diet and physical habits over time without professional support.18 19 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop treatment programmes that can be used in paediatric outpatient care. This feasibility study assesses a 2-year family-based behavioural intervention programme (FBIP) against child obesity implemented in Swedish paediatric outpatient care, where the intervention was provided by the regular nurses and dieticians guided by a manual and supervised by a clinical psychologist. The specific aim of the study was to investigate clinical outcomes and programme adherence.

Methods

A single-group pre- and post-intervention design was used for the study. The primary outcome measure was change in standardised body mass index (z-BMI) between baseline and after 36 months, and 12 months after completion of the programme. The secondary outcome measures were change in the waist:height ratio (WHtR), metabolic parameters and programme adherence. The participants were examined at baseline and after 3, 12 and 24 months of therapy and at follow-up 12 months after completion of the programme.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the study were age 8–<12 years, obesity defined according to the International Obesity Taskforce criteria (above age- and gender-specific cut-offs corresponding to adult BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres, ≥30 kg/m2)20 and absence of other diseases. Both children and parents had to give consent that they were motivated and willing to participate in regular group sessions for the 2-year intervention period, to change eating and physical exercise habits and to note food and beverage intake and physical activity in a diary during the period.

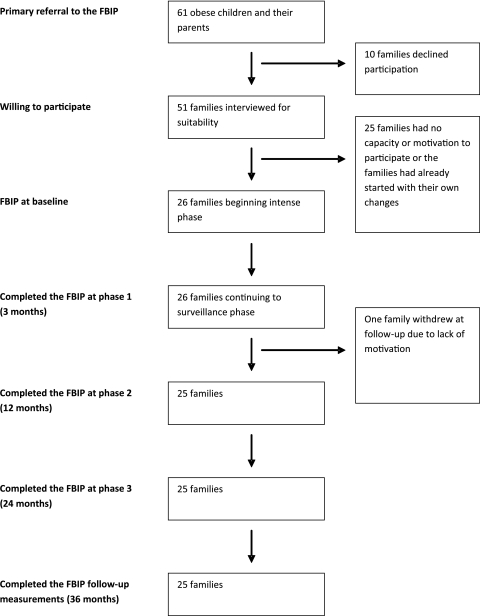

Participant recruitment

Figure 1 presents the flow of subjects referred to the programme and eventually included in the study. School nurses in two municipalities in southeast Sweden with 63 elementary schools were asked to refer obese children and their parents for suitability evaluation, resulting in referral of 61 children. When invited, 10 families declined to participate in the selection interview. The remaining 51 children and their parents were given a structured interview regarding their motivation to change habits and participate in group sessions. Twenty-six children fulfilled all inclusion criteria (table 1). The parent group included biological parents, foster parents and step-parents.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the study of families referral to the family-based behavioural intervention programme (FBIP).

Table 1.

Display of mean age (SD) and z-BMI (SD) for the study population at baseline

| Total (n=26) | Boys (n=14) | Girls (n=12) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 10.9 (0.9) | 10.9 (1.1) | 10.8 (0.7) |

| z-BMI | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.6) |

z-BMI, standardised body mass index.

The FBIP

The FBIP for management of childhood obesity was delivered using the regular community-level health service resources. A manual for group-based family interventions developed by a psychologist and a dietician21 was used as the basis for the programme. The manual contained instructions for family selection (equivalent to the inclusion criteria used in this study) and for tutor-supervised group sessions with obese children and their parents.

The programme started in 2004 and ended in 2006. During the first 3 months, the groups met once weekly (intensive phase 1). Throughout the second phase (months 4–12), group sessions were held once monthly (phase 2) and during the third phase (months 13–24) once every 3 months. The practical goals of the activities in the FBIP included how to promote sustainable and healthy eating habits among the children and stimulate regular physical activity, discussion on influences from commercials on eating and exercise, teaching them how to handle stress and disappointments, solving problems and finding alternative ways to contentment. The tutors wrote down the children's suggestions and changes accomplished in a notebook. After the first phase, the tutors offered individual discussion sessions with the parents. The purpose was to discuss the results the children achieved and how to maintain them.

Programme implementation

Group sessions were conducted in three child groups and three parental groups. Four tutors in the FBIP were paediatric registered nurses. Two tutors were dieticians. The tutors were instructed before and during the intervention by one of the authors of the manual and then continuously supervised during the intervention period by a clinical psychologist.

Group session for children

The 2 h sessions with the children were held after school. At the first meeting, the children received a diary. The diary was used to record the child's eating and physical activity habits and their steps of change. During the first 3 months, they were encouraged to write in the diary every day and thereafter once 1 week before each session. The parents helped the youngest children. The changes were later presented and discussed in the children's group. The tutors and the other children gave feedback on the notes; it was important to increase the children's awareness of their own behaviour. During each group session in phase 1, the children were encouraged to work with two small and realistic steps of changes concerning diet and physical activity until the next session. The tutors presented information handouts regarding diet and physical activity and from those the children were given homework tasks. If the children had not implemented the agreed changes, these were postponed to the next session. Some weeks the children also had to list the rewards they wanted if they had done well with their changes. However, food, drinks or sweets could not be chosen. Physical exercise was not scheduled in the sessions, but sometimes the tutors and the children went for a walk. Each session included a light meal.

The children were reassured that everything that was said was in confidence within the child and parental groups. Therefore, the diaries were not accessible to the researchers.

Group session for parents

The 1.5 h sessions with the parents were held in the evening. Documented changes in the child's eating and physical activity habits were communicated to the parents. The parents were given the same information about diet and physical activity, and they were also given homework tasks from the session content. Moreover, the parents were given various food recipes and information about the risk factors and diseases associated with obesity. Parents presented to the group how the changes had turned out during the week. They gave examples of difficulties that had arisen from a parent's perspective.

Data collection

The participating children were clinically examined at baseline, after 3, 12 and 24 months of group therapy and 12 months after completion of the programme.

Weight wearing trousers and a T-shirt was measured to an accuracy of 0.1 kg. Height was measured using a stadiometer attached to a wall according to standard procedures by two paediatric registered nurses, to an accuracy of 0.5 cm. To compensate for BMI varying with age and gender, the z-BMI was calculated using Swedish national reference values for children from 2001 and the Box transformation formula.22 At each examination, waist circumference measurements were always done by one of the authors (PB) at the navel plane to an accuracy of 0.5 cm. The WHtR was calculated by dividing the waist circumference (in centimetres) by the height (in centimetres).23 24 Fasting blood samples for analysis of glucose, insulin, triglycerides, total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL cholesterol) were taken. The low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol) was calculated according to the Friedewald formula.25 An oral glucose tolerance test was performed only at baseline. After overnight fasting, the child was given a glucose dose of 1.75 g/kg (max 75 g) and plasma glucose was then analysed after 120 min.3 Insulin was analysed using AutoDELFIA from Wallac® (fluoroimmunoassay method), Turku, Finland. Total plasma cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides were analysed using Siemens® Advia-1650 (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, Illinois, USA). Plasma glucose was measured using Hemocue® from HemoCue AB, Ängelholm, Sweden. All blood samples were analysed at an accredited medical laboratory (Vrinnevi Hospital, Norrköping, Sweden). Data on family participation in the intervention were collected from the tutors.

Statistical analysis

Standard descriptive statistics (mean and SD) were computed. Given that variables were normally distributed, paired two-tailed T tests were used for significance testing. The significance level was set at p<0.05. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V.17 was used for the analyses.

Results

Ninety-six per cent (n=25) of the families completed the group sessions. Only one family withdrew from the group sessions after the first 3-month phase of intervention. The child did not feel comfortable in the group and did not see obesity as a problem. Not all children agreed to participate in all examinations, even if they participated in the entire intervention programme (table 2).

Table 2.

Values of anthropometric, body composition and metabolic variables at baseline and at 3-, 12-, 24- and 36-month follow-ups*

| Variables (reference value) | Baseline |

3 months |

12 months |

24 months |

36 months |

0–36 month change |

|||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (95% CI) | p Value | |

| z-BMI | 26 | 3.3 (0.7) | 25 | 3.1 (0.7) | 26 | 3.0 (0.8) | 24 | 2.9 (0.7) | 23 | 2.9 (0.7) | 23 | –0.4 (–0.6 to –0.2) | <0.001 |

| WHtR | 26 | 0.67 (0.06) | 25 | 0.66 (0.07) | 26 | 0.66 (0.07) | 23 | 0.66 (0.07) | 22 | 0.67 (0.08) | 22 | 0 (–0.03 to 0.01) | 0.332 |

| P-fasting glucose (mmol/l) (4.2–6.0) | 26 | 4.6 (0.4) | 25 | 4.7 (0.4) | 26 | 5.1 (0.3) | 23 | 4.9 (0.3) | 23 | 5.0 (0.3) | 23 | +0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) | <0.001 |

| S-fasting insulin (pmol/l) (18–175) | 26 | 78.5 (45.1) | 24 | 76.0 (37.6) | 25 | 77.6 (41.8) | 23 | 80.0 (37.8) | 23 | 76.7 (35.9) | 23 | −1.8 (–27.5 to 16.5) | 0.608 |

| P-LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) (1.2–4.3) | 26 | 2.7 (0.4) | 25 | 2.3 (0.4) | 23 | 2.3 (0.5) | 23 | 2.2 (0.5) | 23 | 2.3 (0.5) | 23 | –0.4 (–0.5 to –0,2) | <0.001 |

| P-HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) (1.0–2.7 girls, 0.8–2.1 boys) | 26 | 1.3 (0.2) | 25 | 1.3 (0.2) | 25 | 1.3 (0.2) | 23 | 1.5 (0.3) | 23 | 1.2 (0.2) | 23 | −0.1 (–0.1 to 0.1) | 0.433 |

| Total P-cholesterol (mmol/l) (3.1–5.2 at 2–12 years) | 26 | 4.4 (0.5) | 25 | 4.0 (0.5) | 25 | 4.1 (0.6) | 22 | 4.3 (0.6) | 23 | 4.1 (0.5) | 23 | –0.3 (–0.5 to –0.1) | 0.004 |

| P-fasting triglycerides (mmol/l) (0.30–1.40 at <10 years, 0.30–1.60 at 10–14 years) | 26 | 1.06 (0.39) | 25 | 1.11 (0.53) | 25 | 1.17 (0.74) | 22 | 1.3 (0.46) | 23 | 1.18 (0.48) | 23 | 0.12 (–0.13 to 0.31) | 0.384 |

One to three children dropped out at each examination, but it was not the same children every time and some children agreed to the weight and height measurements but not the blood sampling or vice versa.

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; P, plasma; S, serum; WHtR, waist:height ratio; z-BMI, standardised body mass index.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome measure, the mean z-BMI, was reduced from 3.3 (SD 0.7) at baseline to 2.9 (SD 0.7) (p<0.001) at the end point (12 months after completion of the programme). A decrease in z-BMI was noted already after 3 months (table 2). The boys had higher z-BMI at baseline (mean 3.5 (SD 0.6)) compared with the girls (mean 3.0 (SD 0.6)) (p=0.028). At the 36-month follow-up, there were no gender differences in the decrease in z-BMI (p=0.141) (data not shown). Regarding the secondary outcome measures, there was no significant reduction of WHtR (table 2). There was a decrease in the LDL cholesterol (p<0.001) and total cholesterol (p<0.01) in the study group at the end point (12 months after completion of the programme), but no significant differences in HDL cholesterol or triglyceride values (table 2). All children displayed normal values for the oral glucose tolerance test at baseline (data not shown). Fasting glucose was higher at the end point measurement (table 2). However, all biomedical markers were within the normal range throughout the study.

Discussion

In this feasibility study, we found that obese children who agreed to a 2-year FBIP delivered in a paediatric outpatient care setting had reduced their z-BMI 12 months after completion of the programme. The mean decline in z-BMI was 12.1%. Even though the weight reduction was limited, it could be of importance in the prevention of long-term complications. Also moderate changes in BMI among children are known to influence metabolic risk indicators for cardiovascular disease.26

The small study sample and the single-group design imply that the observed decline in z-BMI cannot be firmly interpreted as an effect of the intervention programme. Without a randomised control group, it is impossible to know if the decrease in z-BMI was an effect of the intervention programme per se. One bias in this study could be that the intervention procedure selected only highly motivated families, who might have managed their children's weight without the FBIP support.

Among secondary end point measures, the WHtR showed no change; the measurements for lipid status showed favourable trends. The results would have been even more convincing if all the secondary outcome measures had displayed similar trends. WHtR did not change, but perhaps the decline in z-BMI was too low to affect this measurement. The fasting glucose values increased at the follow-up 12 months after completion of the programme. A Swedish study points out that BMI, level of physical activity, seasonal variations in physical activity and biological age (pubertal development) must be taken into consideration when interpreting clinical laboratory data.27 Puberty signs were not consistently investigated in this study, which made it more difficult to interpret the biochemical data. Initial pubertal development in girls starts at approximately 10.9 years of age (range of 8.5–13.3 years) and in boys at 11.9 years of age on average (range 10.1–13.7 years).28 Some children in this study may thus have reached the age for initiation of pubertal development when they started the FBIP (table 1). It can be inferred that at least the interpretation of the metabolic parameters is complicated by the fact that the children entered puberty during the study period. It is thus possible that the higher blood glucose at follow-up could be explained by older age and more mature pubertal stage and not deterioration of metabolic status.

A methodological strength of this study is that the primary end point measurement was performed 12 months after completion of the intervention programme. Although this follow-up period is longer than in many other studies, an even longer follow-up is necessary to evaluate the persistence of intervention effects. For instance, a randomised study of a 6-month obesity programme in children aged 7–9 years in which a family-based group treatment was compared with routine counselling showed positive short-term effects,29 but no difference in z-BMI at 2 and 3 years after the start of the intervention.30 Another strength is that all participants were included in the data analysis at the study end point whether or not they completed the intervention. To improve the reliability of follow-up measurements, the height was measured by the same two paediatric registered nurses and waist circumference was always measured by the same person.

An interesting observation is the high rate of families (96%) completing the 2-year intervention programme. A previous study has shown that high family adherence is an important success factor for long-term weight reduction in childhood obesity.31 In comparison, results from the similar Families for Health Programme provided in a community setting in England reported that only 18 of 27 (67%) children completed a 3-month programme.32 One reason for the more favourable adherence to the present FBIP could be that the families were interviewed before starting the group sessions and estimated to be highly motivated to act on the obesity and to participate in the whole-group programme. Another factor contributing to the high adherence in this study could be the weight reduction during the intensive phase at the beginning of the programme. Initial weight decrease has been suggested to be an important factor for success and for reducing the risk of dropout from the treatment programme.33 A recent assessment of an outpatient treatment programme with an 8-year follow-up of 90 obese children with a mean age of 10.1 years at baseline indicated that the mean reduction of 8% in adjusted BMI was a result of the children's success at the beginning of their treatment.34 Another 1-year outpatient obesity intervention programme of 170 children with a mean age 10.5 years showed promising results regarding weight outcomes 3 years after the end of the programme. Also here, the weight reduction was interpreted to be connected to the initial weight reduction in the first 3 months of the intervention programme.35

The recent Cochrane review of randomised controlled trials of interventions on childhood obesity reported that family-based behavioural lifestyle intervention programmes are superior to regular care and self-help in the short and the long term.2 Our feasibility study suggests that a long-term obesity management FBIP supported by a detailed manual can be implemented in routine paediatric outpatient care. We agree with the recommendations from the Cochrane review that more research is needed on obesity treatment in children and adolescents, especially large randomised effectiveness studies of different intervention programmes with evaluations of long-term outcomes using changes in z-BMI and metabolic parameters as measures. In addition, we agree with the conclusion from the review that more research is needed to evaluate psychosocial, ethnic and cost-effectiveness aspects.

Conclusions

This feasibility study of an FBIP for management of childhood obesity in a paediatric outpatient care setting using a single-group pre- and post-intervention design showed promising outcomes and high adherence with 96% of families completing the 2-year intervention. The detailed manual and the structured programme make it possible for available primary care or paediatric outpatient staff to lead groups. However, this FBIP assessment must be confirmed in a larger randomised controlled trial with a longer follow-up period before it can be implemented on a larger scale. Another interesting topic for further research is a comparison of the cost-effectiveness between the FBIP and other family-based behavioural interventions in treating obese children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the the tutors, school nurses for referring families, and to all participating children and their parents. We also thank statistician Olle Eriksson, PhD, for assistance with the data analyses.

Footnotes

To cite: Teder M, Mörelius E, Bolme P, et al. Family-based behavioural intervention programme for obese children: a feasibility study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000268. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000268

Contributors: MT was involved in the conception and design of the project, as well as the analysis and interpretation of the data. She drafted and revised the manuscript and provided intellectual content. EM was involved in the conception and design of the project and in the interpretation of the data. She drafted and revised the manuscript, providing intellectual content. PB conceived and designed the project. He drafted and revised the manuscript, providing intellectual content. MN was involved in the conception and design of the project and in the interpretation of the data. She revised the manuscript, providing intellectual content. JE helped with data interpretation, revised the manuscript and provided intellectual content. TT accepts direct responsibility for the manuscript. He was involved in the design of the project and the interpretation of the data. He drafted and revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Crown Princess Lovisa's Foundation for Paediatric Care, Procter & Gamble, the Carl and Albert Molins Memorial Foundation, Novo Nordisk Scandinavia, Eli Lilly, Faculty of Health Sciences and Department of Social and Welfare Studies Linköping University Sweden.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the research ethics committee at Faculty of Health Sciences, Linköping University, Sweden (dnr. 03-600).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors are willing to share data from the study with researchers having an interest in comparative studies on family intervention effects.

References

- 1.Lobstein L, Baur R. Uauy for the IASO International obesity taskforce. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev 2004;5:4–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, et al. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD001872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications, Report of a WHO Consultation; Part 1:Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva: Department of Noncommunicable disease Surveillance, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koplan JP, Liverman CT, Kraak VI. Committee on prevention of obesity in children and Youth. Preventing childhood obesity: health in the balance: executive summary. J Am diet Assoc 2005;105:131–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marild S, Bondestam M, Bergstrom R, et al. Prevalence trends of obesity and overweight among 10-year-old children in western Sweden and relationship with parental body mass index. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:1588–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sundblom E, Petzold M, Rasmussen F, et al. Childhood overweight and obesity prevalences levelling off in Stockholm but socioeconomic differences persist. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1525–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reilly JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, et al. Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis child 2003;88:748–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:891–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mossberg HO. 40-Year follow-up of overweight children. Lancet 1989;2:491–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flodmark CE, Lissau I, Moreno LA, et al. New insights into the field of children and adolescents' obesity: the European perspective. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28:1189–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowen M. The use of family theory in clinical practice. Compr Psychiatry 1966;7:345–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wachs TD. Multiple influences on children's nutritional deficiencies: a systems perspective. Physiol Behav 2008;94:48–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pocock M, Trivedi D, Wills W, et al. Parental perceptions regarding healthy behaviours for preventing overweight and obesity in young children: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev 2010;11:338–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yackobovitch-Gavan M, Nagelberg N, Phillip M, et al. The influence of diet and/or exercise and parental compliance onhealth-related quality of life in obese children. Nutr Res 2009;29:397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reinehr T, Kleber M, Lass N, et al. Body mass index patterns over 5 y in obese children motivated to participate in a 1-y lifestyle intervention: age as a predictor of long-term success. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:1165–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braet C, Van Winckel M, Van Leeuwen K. Follow-up results of different treatment programs for obese children. Acta Paediatr 1997;86:397–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West F, Sanders MR, Cleghorn GJ, et al. Randomised clinical trial of a family-based lifestyle intervention for childhood obesity involving parents as the exclusive agents of change. Behav Res Ther 2010;48:1170–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitlock EA, O'Connor EP, Williams SB, et al. Effectiveness of weight management programs in children and adolescents. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2008:1–308 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitlock EP, O'Connor EA, Williams SB, et al. Effectiveness of weight management interventions in children: a targeted systematic review for the USPSTF. Pediatrics 2010;125:e396–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonnedal U, Pettersson C. [Group Treatment Of Children With Overweight And Obesity; Investigation Interview (MORSE) and Treatment Manual for Children and Parents]. Gruppbehandling av barn med övervikt och fetma; Utredningsintervju (MORSE) och Behandlingsmanual för barn och föräldrar (In Swedish). 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlberg J, Luo ZC, Albertsson-Wikland K. Body mass index reference values (mean and SD) for Swedish children. Acta Paediatr 2001;90:1427–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashwell M, Hsieh SD. Six reasons why the waist-to-height ratio is a rapid and effective global indicator for health risks of obesity and how its use could simplify the international public health message on obesity. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2005;56:303–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nambiar S, Truby H, Abbott RA, et al. Validating the waist-height ratio and developing centiles for use amongst children and adolescents. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:148–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson C, Hernell O, Lind T. Moderately elevated body mass index is associated with metabolic variables and cardiovascular risk factors in Swedish children. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:102–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wennlof AH, Yngve A, Nilsson TK, et al. Serum lipids, glucose and insulin levels in healthy schoolchildren aged 9 and 15 years from Central Sweden: reference values in relation to biological, social and lifestyle factors. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2005;65:65–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bramswig J, Dubbers A. Disorders of pubertal development. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2009;106:295–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalavainen MP, Korppi MO, Nuutinen OM. Clinical efficacy of group-based treatment for childhood obesity compared with routinely given individual counseling. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1500–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalavainen M, Korppi M, Nuutinen O. Long-term efficacy of group-based treatment for childhood obesity compared with routinely given individual counselling. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:530–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Arslanian SA, et al. Family-based treatment of severe pediatric obesity: randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2009;124:1060–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson W, Friede T, Blissett J, et al. Pilot of ‘families for health': community-based family intervention for obesity. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:921–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elfhag K, Rossner S. Initial weight loss is the best predictor for success in obesity treatment and sociodemographic liabilities increase risk for drop-out. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79:361–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moens E, Braet C, Van Winckel MV. An 8-year follow-up of treated obese children: children's, process and parental predictors of successful outcome. Behav Res Ther 2010;48:626–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinehr T, Temmesfeld M, Kersting M, et al. Four-year follow-up of children and adolescents participating in an obesity intervention program. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1074–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.