Abstract

Objective

To identify factors associated with intention to attend a hypothetical eye health test and provide an evidence base for developing an intervention to maximise attendance, for use in studies evaluating glaucoma screening programmes.

Design

Theory-based cross-sectional survey, based on an extended Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and the Common Sense Self-Regulation Model, conducted in June 2010.

Participants

General population including oversampling from low socioeconomic areas.

Setting

Aberdeenshire and the London Boroughs of Lewisham and Southwark, UK.

Results

From 867 questionnaires posted, 327 completed questionnaires were returned (38%). In hierarchical regression analysis, the three theoretical predictors in the TPB (Attitude, Subjective norm and Perceived Behavioural Control) accounted for two-thirds of the variance in intention scores (adjusted R2=0.65). All three predictors contributed significantly to prediction. Adding ‘Anticipated regret’ as a factor in the TPB model resulted in a significant increase in prediction (adjusted R2=0.74). In the Common Sense Self-Regulation Model, only illness representations about the personal consequences of glaucoma (How much do you think glaucoma would affect your life?) and illness concern (How concerned are you about getting glaucoma?) significantly predicted. The final model explained 75% of the variance in intention scores, with ethnicity significantly contributing to prediction.

Conclusions

In this population-based sample (including over-representation of lower socioeconomic groupings), the main predictors of intention to attend a hypothetical eye health test were Attitude, Perceived control over attendance, Anticipated regret if did not attend and black ethnicity. This evidence informs the design of a behavioural intervention with intervention components targeting low intentions and predicted to influence health-related behaviours.

Article summary

Article focus

The current UK practice of opportunistic case finding during routine sight tests misses a majority of those with glaucoma. Early detection and treatment of glaucoma reduces the risk of blindness.

The feasibility and cost-effectiveness of screening programmes is largely determined by uptake by the target population.

This study identified empirical evidence, based on models of behaviour change, to inform the design of an intervention to maximise uptake.

Key messages

Intention to attend an eye health check to detect glaucoma is associated with positive Attitude, Perceived control over screening attendance, Anticipated regret if test is not attended, perceived consequences of glaucoma and black ethnicity. These factors can be targeted in an intervention to maximise uptake.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study is the largest of its kind and uses a robust methodology based on plausible models of change to identify potential barriers to attendance for eye care.

The response rate was 38%, which is higher than generally achieved in similar population-based surveys.

There was evidence to suggest that this sample was representative of the target population (general population with over-representation of black ethnicity or of low socioeconomic status).

Introduction

Glaucoma is a leading cause of avoidable and irreversible blindness worldwide.1 In the UK, glaucoma is second to macular degeneration as the most common cause of blindness. If glaucoma is identified early, treatment is effective at reducing progressive disease.2 It is estimated, based on a synthesis of the available evidence, that the current UK practice of opportunistic case finding during routine sight tests misses a majority of those with glaucoma.3 Identified risk factors for developing the most common form of glaucoma (open angle glaucoma) include: age (>60 years), family history of glaucoma in a first-degree relative, myopia, diabetes and black ethnicity.3 Late presentation, older age and poor adherence to treatment are important determinants of blindness.4–6 Late presentation may be due to patient delay in terms of attendance for testing, process delay in terms of missed diagnosis or system delay leading to delayed access to treatment.7 There is evidence to suggest that uptake of eye care services may be lower in groups at risk of glaucoma blindness. In the UK, uptake of current eye care services is lower in black ethnic groups (38% of those aged 55 years and older compared to 80% of the same age group in the general population).8 In addition, lower socioeconomic groups and/or black and other ethnic minority groups are less likely to attend for health promotion and preventive services more generally.9 10 Considering the public health importance of glaucoma and that early detection and treatment reduce the risk of blindness, a screening programme could be considered.11 However, there is insufficient evidence from high-quality studies that the benefits of glaucoma screening or enhanced case detection programmes outweigh any potential harm (such as raising anxiety levels).3 Such evidence would be best gathered in the context of a randomised controlled trial.11 For public health programmes, a major determinant of both feasibility and cost-effectiveness is the level of uptake by the target population.12 Uptake involves intentional behaviour (eg, intend to go to screening appointment) and is likely to be influenced by the way people think (ie, their cognitions) about the action (attending an eye test) or the condition (glaucoma). We investigated the factors that predict intention to attend an ‘eye health test’ based on (1) the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)13 and (2) the Common Sense Self-Regulation Model (CS-SRM).14 The TPB proposes that intentions are determined by Attitude (beliefs about whether the benefits outweigh the costs), Subjective norm (perceived normative pressures) and Perceived control over the behaviour. There is consistent evidence that adding ‘Anticipated regret’ as a factor (ie, beliefs about whether feelings of regret will follow from inaction) to the TPB model increases prediction of intention and behaviour.15 The model including Anticipated regret is hereafter referred to as the extended TPB model. The CS-SRM proposes that cognitive representations (a ‘mental picture’) or emotional representations (worry or concern) about a health threat lead to behaviours that assist in coping with the threat. Ideally, an intervention to maximise uptake of a screening programme would be based on empirical evidence of an association between these cognitive or emotional factors and intention to attend the eye test to ensure that the intervention is based on identified (rather than assumed) barriers to uptake. Therefore, we conducted a study to identify the predictors of intention to attend for eye testing, using the factors proposed by the extended TPB to predict intention and the factors proposed by the CS-SRM to lead to coping behaviours. Specifically, we investigated the associations between intention to attend an eye test and:

measures of how people think about attending an ‘eye health test’ (Intention, Attitude, Subjective norm, Perceived Behavioural Control, Anticipated regret);

measures of how people think and feel about glaucoma (illness representations, ie, Consequences, Timeline, Personal control, Treatment control, Identity, Concern, Coherence, Emotional representation);

other personal attributes (ie, socio-demographic variables that are known risk factors for glaucoma and knowledge of glaucoma).

Identified predictors would provide an evidence base for developing a behavioural intervention to maximise uptake of glaucoma screening or enhanced case detection programmes.

Methods

Study design and population

We used a cross-sectional survey design to identify factors associated with intention to attend an eye health test, among members of the general population on the edited electoral register in two UK locations: Aberdeenshire (to target a mixture of urban and rural Scottish residents) and the London Boroughs of Lewisham and Southwark (areas with a high Black African–Caribbean population). The initial sample was obtained from a commercial company specialising in the supply of publically available data (names and addresses) for use in research.16 We requested a sample that was systematically biased towards people older than 40 years, in lower socioeconomic groups and/or of African–Caribbean ethnicity.3 17 We used the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2007 and the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) to independently assess the socioeconomic status of the initial sample. These indices provide relative ranking of geographic areas (data zones) within England or Scotland according to the levels of deprivation. The IMD is based on 37 different indicators of deprivation, weighted and combined to give a relative ranking for data zones ranging from most deprived (rank 1) to least deprived (rank 32 482). The SIMD uses different indicators to the IMD but provides a relative rank for Scottish data zones ranging from most deprived (rank 1) to least deprived (Rank 6505).

Materials

We used a questionnaire based on the extended TPB and the CS-SRM to identify factors associated with intention to attend an eye health test. Twenty factors were measured: four from the TPB, eight from the CS-SRM and eight medical and demographic factors (see below). We used the phrase ‘new eye health test’ and not ‘glaucoma screening test’ in the questionnaire to minimise anxiety that may be caused if the selected members of the public mistakenly believed that we had approached them after identifying an underlying ‘problem’ with their eyes.

The questionnaire was presented in three sections. Section A contained 18 items based on the components of the extended TPB (Intention, Attitude, Subjective norm, Perceived Behavioural Control and Anticipated regret), with items measured on 7-point response scales with consistent direction (ie, high scores indicating high intention, Perceived Behavioural Control and Anticipated regret, positive Attitude and more positive normative pressures). Items designed to assess the same construct were separated and presented in a non-systematic order (in accordance with TPB guidance).13 18 Examples of section A items are shown in table 1. The full questionnaire is available in supplementary file 1. Section B (table 1) assessed illness representations and emotional representations about glaucoma using items adapted from the Brief Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (Brief IPQ).19 The Brief IPQ is a validated questionnaire that measures the components of the CS-SRM that are proposed to influence health-related coping behaviour. Rewording of items for specific conditions and for people without a diagnosis are part of the standard use of the questionnaire,20 and items in section B were adapted to be appropriate to this study. Each item assesses a different domain of illness representations, on a 10-point scale, and each is analysed separately.19 An item assessing knowledge of the term glaucoma (Have you heard of the eye condition glaucoma?) preceded the Brief IPQ items in section B.

Table 1.

Sample questionnaire items designed to assess theoretical predictors

| Items designed to measure each component | Response options | |

| Section A | ||

| Dependent variable: intention (items: A1, A8, A17) | If I received a letter inviting me to attend for an eye health test I would attend | Strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) |

| Predictors | ||

| Attitude (items: A21A–A21F) | For me, attending an eye health test would be… | Not worthwhile (1) to worthwhile (7); bad use of my time (1) to good use of my time (7) |

| Subjective norm (items: A6, A19, A20) | Most people who are important to me would think that I should attend an eye health test | Strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) |

| Perceived behavioural control (items: A5, A14, A15, A22) | Whether I attend an eye health test would be entirely up to me | Strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) |

| Anticipated regret (items: A7, A18) | If I was invited for an eye health test and I did not attend I would later wish I had | Strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) |

| Section B (items B2–B9) | 10-point response options | |

| Consequences | How much do you think glaucoma would affect your life? | No effect at all (1) to would severely affect my life (10) |

| Timeline | How long do you think glaucoma lasts? | Very short time (1) to forever (10) |

| Personal control | Once a person has been diagnosed with glaucoma, how much control do you think they have over the disease? | Extreme amount of control (1) to absolutely no control (10) |

| Treatment control | How helpful do you think treatment is for glaucoma? | Extremely helpful (1) to not at all (10) |

| Identity | How much do you think a person with glaucoma would experience symptoms | No symptoms at all (1) to many sever symptoms (10) |

| Concern | How concerned are you about getting glaucoma? | Not at all concerned (1) to extremely concerned (10) |

| Coherence | How well do you feel you understand glaucoma? | Understand very clearly (1) to do not understand at all (10) |

| Emotional representation | How much does the possibility of getting glaucoma affect you emotionally? | Not at all affected emotionally (1) to extremely emotionally affected (10) |

Full questionnaire included as a supplementary file.

Section C of the questionnaire contained socio-demographic and general health items (gender, general health status, time since last eye test) and items to assess identified risk factors for glaucoma (age; diabetes, myopia; family history of glaucoma and ethnicity). In addition, unique study identification numbers enabled us to identify the location (London or Aberdeenshire) and socioeconomic status of the invited sample and responders.

We pilot tested the questionnaire with two members of the general population to assess usability and identify any need for clarification of wording. This resulted in changes to the instruction sheet to emphasise our interest in the honest opinions of participants and not socially desirable responses.

Procedure

The questionnaire was mailed to 867 potential participants (421 in London and 446 in Aberdeenshire) in June 2010 together with an information letter (see supplementary file 2) and reply paid envelope. One reminder was sent to non-responders 2 weeks later. The return of a completed questionnaire was considered as consent to take part. Ethical approval for the survey was obtained from the University of Aberdeen College of Life Sciences and Medicine Ethics Review Board (Ref: CERB/2010/4/507). The postal survey reported in this paper formed part of a larger study to assess the feasibility of conducting a randomised controlled trial of glaucoma screening.21

Sample size and statistical analyses

Multiple regression approaches were used to identify factors associated with intention to attend a hypothetical eye health test. The recommended minimum sample is calculated as 50+8 m, where m is the number of predictor variables.22 This study design involved a total of 20 potential predictor variables, and the minimum sample size required was thus 210. The internal consistency of each multi-item measure was assessed using Cronbach's α (for measures with three or more items) and Pearson's correlation coefficient (for the 2-item measure of Anticipated regret), using an acceptability criterion of α>0.65 and r>0.5, respectively.23 In addition, measures of central tendency and dispersion were computed for measures in sections A and B.

The primary analysis addressed the prediction of intention to attend an eye health test. A four-step hierarchical regression analysis explored the predictive value of (1) the TPB measures, (2) Anticipated regret, (3) the Brief IPQ measures and (4) socio-demographic and general health variables in explaining variance in participants' intention to attend a test. Variables that did not contribute significantly to the model (p>0.05) at their point of entry were excluded in later steps. The TPB constructs were entered at step 1 as these are proposed by the theory to be the proximal predictors of intention. Anticipated regret was added at step 2 as this variable represents an extension of the TPB. Step 3 involved the addition of the Brief IPQ items (as they represent cognitions at a more contextual level). At step 4, demographic and general health variables were added (as they represent the broader personal context in which screening behaviour would be performed). Prior to inclusion in the model, independent sample t tests were performed to compare intention scores of dichotomised demographic and general health variables. Only those variables for which there was a significant difference in intention scores were added to the regression model at step 4. There was no imputation of missing data.

Results

Response rates and responder characteristics

Of the 867 questionnaires sent out, 327 completed questionnaires were returned, representing a response rate of 38%. The response rate differed by geographical area with London achieving 24% (101/421) and Aberdeenshire 51% (226/446). However, the areas did not differ on the key variable we were attempting to predict (intention) (p=0.084) so we combined the two samples for the primary analysis. Of the 11 445 possible data points in the returned questionnaire, 2.1% of data were missing. The mean (SD) age of respondents was 54 (12) years. The socioeconomic status of respondents, in both locations, was representative of those sampled and achieved the desired weighting towards people in lower socioeconomic groups: mean IMD rank of the London sample was 4818 versus 4809 for respondents; mean SIMD of the Aberdeenshire sample was 2818 versus 2914 for respondents. The most commonly reported health status was ‘good’ (41%). Ten per cent of the sample reported black ethnicity (table 2), and 81% reported having an eye test within the previous 3 years.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics from both locations

| Sample characteristic | n (%) |

| Male | 143 (43.7) |

| General health status | |

| Excellent | 18 (5.5) |

| Very good | 79 (24.2) |

| Good | 134 (41.0) |

| Fair | 71 (21.7) |

| Poor | 18 (5.5) |

| Heard of the term glaucoma | 280 (85.6) |

| Last eye test within 3 years | 265 (81.0) |

| Black ethnicity (Black British, Caribbean, African) | 33 (10.1) |

| Diabetic | 37 (11.3) |

| Short-sighted | 144 (44.0) |

| Family history of glaucoma | 53 (16.2) |

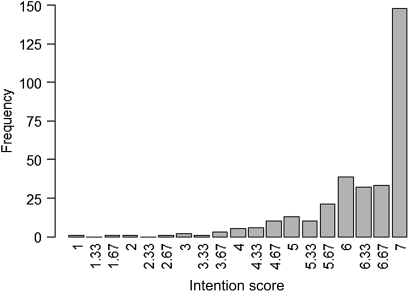

Internal consistency of the extended TPB measures was satisfactory with reliabilities (Cronbach's α) of the Intention, Attitude, Subjective norm and Perceived Behavioural Control scales >0.65 and the Anticipated regret scale >0.5 (Pearson's correlation coefficient). Summary statistics for each variable are shown in table 3. All variables representing the extended TPB had medians >6.3 (on a scale of 1–7), suggesting potential ceiling effects (generally positive views and intentions). Although intention was generally high (figure 1), there was still a substantial proportion of respondents (54.7%) who reported a mean intention score of <7, indicating some reservation in their intention to attend. All measures of the CS-SRM variables, apart from Treatment control, had medians >5 (on a scale of 1–10), representing generally negative representations about glaucoma (table 3).

Table 3.

Summary statistics for theory-based variables in the analysis including correlations with intention scores

| Section and factor | Mean (SD) | Median (Q1, Q3) | Pearson's correlation with intention score |

| Section A: attending an eye health test | |||

| Intention | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.7 (6.0, 7.0) | |

| Attitude | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.7 (6.0, 7.0) | 0.67** |

| Subjective norm | 6.0 (1.2) | 6.3 (5.3, 7.0) | 0.59** |

| Perceived behavioural control | 6.3 (0.8) | 6.5 (6.0, 7.0) | 0.71** |

| Anticipated regret | 6.0 (1.2) | 6.5 (5.5, 7.0) | 0.76** |

| Section B: illness and emotional representations of glaucoma | |||

| Consequences | 8.6 (1.9) | 9.5 (8.0, 10.0) | 0.44** |

| Timeline | 8.6 (2.0) | 10.0 (8.0, 10.0) | 0.24** |

| Personal control | 6.2 (2.7) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | −0.43 |

| Treatment control | 3.2 (2.4) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 0.28** |

| Identity | 6.8 (2.4) | 7.0 (5.0, 8.5) | 0.17** |

| Illness concern | 7.3 (2.8) | 8.0 (5.0, 10.0) | 0.35** |

| Coherence | 6.6 (2.7) | 7.0 (5.0, 9.0) | 0.16** |

| Emotional representation | 6.0 (2.8) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 0.25** |

Scales ranged from: (1) negative intention/belief to (7) positive intention/belief (section A); (1) positive representation of glaucoma to (10) negative representation of glaucoma (section B).

**p<0.01.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of mean intention scores (possible range 1–7).

The Pearson's correlations between intention to attend an eye health test and the theoretical predictor variables are shown in table 3. Higher intention to attend was significantly associated with all the predictors as proposed by the theories.

Intention scores for groups defined by demographic and general health variables are shown in table 4. There was a significant difference in the intention scores for respondents of black and non-black ethnicity and for respondents who reported that they had heard of glaucoma compared with those who had not. Both variables were therefore included in the regression model at step 4. The other five variables in table 4 were excluded. A further risk factor for glaucoma, the continuous variable ‘age’, was also entered at step 4 as it was highly correlated with intention to attend an eye health screening test (Spearman's rank correlation coefficient=0.155, p=0.006).

Table 4.

Independent sample t tests on intention scores

| N† | Mean intention score | SD | t | p | |

| Heard of glaucoma | |||||

| Yes | 280 | 6.33 | 0.91 | 2.04 | 0.047** |

| No | 44 | 5.87 | 1.43 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 143 | 6.28 | 0.88 | 0.17 | 0.868 |

| Female | 177 | 6.30 | 1.05 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| All black ethnicities | 33 | 5.80 | 1.51 | 2.05 | 0.048** |

| All other ethnicities | 281 | 6.35 | 0.87 | ||

| Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 37 | 6.41 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.476 |

| No | 278 | 6.29 | 0.96 | ||

| Last eye test | |||||

| Within the last 3 years | 265 | 6.29 | 1.00 | 0.17 | 0.867 |

| More than 3 years ago/never | 56 | 6.31 | 0.86 | ||

| Short-sighted | |||||

| Yes | 144 | 6.30 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.402‡ |

| No | 107 | 6.19 | 1.14 | ||

| Don't know | 61 | 6.44 | 0.82 | ||

| Family history of glaucoma | |||||

| Yes | 53 | 6.43 | 0.69 | 1.11 | 0.269‡ |

| No | 172 | 6.27 | 1.00 | ||

| Don't know | 94 | 6.30 | 0.99 | ||

Numbers for each variable do not add up to 327 as some participants did not provide the information.

The test was between ‘yes’ and ‘no’ with those answering ‘don't know’ left out. When the t tests were repeated with the variables coded dichotomously (yes vs ‘not yes’), the t tests remained non-significant.

**p<0.05.

The results of the hierarchical regression analysis are presented in tables 5 and 6. At step 1, the three theoretical predictors of the TPB (Attitude, Subjective norm and Perceived Behavioural Control) accounted for two-thirds of the variance in intention scores (adjusted R2=0.65), and all three predictors contributed significantly to prediction. The addition of Anticipated regret at step 2 resulted in a significant increase in prediction (adjusted R2=0.74). At step 3, only representations about consequences of the condition (How much do you think glaucoma would affect your life?) and illness concern (How concerned are you about getting glaucoma?) significantly predicted. The final model (step 4) explained 75% of the variance in intention scores, with ethnicity significantly contributing to prediction.

Table 5.

Hierarchical regression model summary for predicting intention to attend and eye test

| Model | R2 | R2 change | p Value |

| 1 | 0.651 | 0.651 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.738 | 0.088 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.747 | 0.009 | 0.006 |

| 4 | 0.752 | 0.004 | 0.025 |

Table 6.

Coefficients of terms in the final model (model 4) for predicting intention to attend and eye test

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | p Value |

| (Constant) | −0.067 | 0.248 | −0.556 to 0.421 | 0.786 |

| Attitude | 0.176 | 0.039 | 0.098 to 0.253 | 0.000** |

| Subjective norm | 0.067 | 0.030 | 0.007 to 0.126 | 0.028** |

| Perceived Behavioural Control | 0.407 | 0.046 | 0.316 to 0.499 | 0.000** |

| Anticipated regret | 0.298 | 0.033 | 0.232 to 0.363 | 0.000** |

| Consequences of glaucoma | 0.045 | 0.016 | 0.013 to 0.078 | 0.006** |

| Illness concern | 0.016 | 0.011 | −0.006 to 0.037 | 0.153 |

| Black ethnicity | −0.212 | 0.094 | −0.396 to −0.027 | 0.025** |

**p<0.05.

Discussion

This study showed that, in this population-based sample, intention to attend an eye health test was relatively high and was related to Attitude, Subjective norm, Perceived Behavioural Control, Anticipated regret, perceived consequences of having glaucoma and ethnicity. In other words, people who reported that they were in favour of attending an eye health test, that other people would approve of their attending, that they would be able to attend and that they would regret not attending were more likely to report strong intention to attend such a test. (The effect size for the association between Subjective norm and intention was small, so Subjective norm will not be considered further). In this sample, in which lower socioeconomic status was well represented, the theory did better in predicting intention than is usually reported in the literature (ie, 65% in this study, 40% frequently reported) demonstrating the theoretical coherence of the data.24 People who reported that glaucoma would negatively affect their life (consequences of glaucoma) were more likely to report strong intention to attend an eye health test, but the effect size was small. Intention was not uniquely predicted by knowledge or perceptions about glaucoma nor was it associated with age when analysed with the other predictors. However, people of black ethnicity, known to be at increased risk of developing glaucoma, were less likely than those of other ethnicities to report strong intention to attend such a test. This pattern of findings can be used as an evidence base for developing an intervention to be evaluated in a possible population-based screening trial.

Implications of this evidence base for designing a behavioural component of a complex intervention to improve glaucoma detection

Intention scores were generally high, as were measures of other variables that represented the way people thought about attending a hypothetical eye health test. The data indicate that a large proportion of this sample was highly receptive to the idea of an eye health programme to detect glaucoma. Motivation (ie, high intention24) is thus possibly not a barrier to uptake of a screening programme for the majority of this sample. However, there was still a substantial proportion of the sample (54.7%) who reported some uncertainty about their intention (ie, mean intention score <7) (figure 1). Thus, an intervention could include components to increase motivation to attend. The distribution of intention scores (median of 6.7 on a 7-point scale) also indicated that many in the sample reported that they were highly motivated to re-arrange other priorities in order to attend a screening test. This is not to say that all people who strongly intend to attend would actually do so. We were unable to estimate the likely size of the ‘intention–behaviour’ gap for attendance at this hypothetical eye health test as a glaucoma screening programme is not current policy. However, the literature suggests that around 50% of people who intend to perform a health-related behaviour actually translate that intention into action.25 Thus, intervention components could target ‘post-intentional’ (action) processes to support increased uptake of a screening programme or an enhanced case detection programme by assisting people to translate their high intentions into actual behaviour. The inclusion of non-modifiable socio-demographic and general health variables in the predictive model enabled us to determine that, in addition to targeting modifiable predictors of intention to attend an eye test, it would be appropriate to develop an intervention that is tailored to different ethnic groups. However, there was no evidence to suggest that tailoring to different age groups is warranted.

In summary, an intervention to increase uptake could include components to increase motivation and components to increase action. In addition, tailoring of the intervention to increase motivation in people of black ethnicity should be considered (eg, a letter of invitation endorsed by a relevant community leader). Methods have recently been reported for developing interventions based on the evidence reported here.26 Hence, it would be feasible to design an intervention to support both (1) motivation to attend and (2) action (attendance for testing). An intervention to increase motivation could include techniques such as persuasive communication (eg, argument in favour of attending, delivered by letter, mass media or an individual matched to the target group) to target people's beliefs about the benefits of screening (Attitude, Anticipated regret) and factors likely to make it easier to attend the test (Perceived Behavioural Control). In addition, prompts and/or reminders (eg, letters or phone calls) and contracts (ie, written and signed agreements to attend) could make actual attendance more likely among those who are motivated to attend for screening.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study is the largest of its kind and uses a robust methodology based on plausible models of change to identify potential barriers to attendance for eye care. We avoided the term ‘glaucoma screening’ in the participant information sheet and questionnaire, instead using the phrase ‘new eye health tests’. Our purpose was to minimise potential participant anxiety that they had been specifically targeted in a research study about a serious condition. However, the use of a generic description of the proposed eye test has generated results that are applicable to development of interventions for improving attendance at eye care services more generally.

The response rate was 38%, which is higher than generally achieved in similar population-based surveys.27 28 There was evidence to suggest that this sample was representative of the target population (general population with oversampling from low socioeconomic areas). Furthermore, the intention to attend an eye health test did not differ significantly between the two locations. The proportion of participants reporting having their eyes tested in the last 3 years (81%) was consistent with findings in the general population.8 The socioeconomic status and sample characteristics of responders and non-responders suggested that responders were not distinguishable from non-responders on these variables, and the desired weighting towards people in lower socioeconomic groups was achieved. Furthermore, groups that might be at higher risk of developing glaucoma including hard-to-reach groups were well represented in the sample. For example, 2.0% of the UK population29 but 10% of our sample are of black ethnicity. In addition, there was a good spread of general health status in the sample, but the proportion reporting excellent health (5.5%) was lower than the UK average (21.3%).30

Conclusions

This study identified that, in a population-based sample (including over-representation of lower socioeconomic groupings), the main predictors of intention to attend for sight testing to detect glaucoma were Attitude, Perceived control over attendance, Anticipated regret if not attended and black ethnicity. This evidence will inform the design of a behavioural intervention to maximise screening uptake. The intervention components that are the likely ‘best bets’ for targeting these factors can be selected using a tool systematically developed for this purpose.26 This study illustrates the evidence base that is required to inform the development of interventions to influence health-related behaviours.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marion Campbell, Augusto Azuara-Blanco and Jemaima CheHamzah from the Glaucoma screening Platform Study research group for their contribution to the development of the larger study and their guidance throughout its conduct. We thank the Glaucoma screening Platform Study advisory panel including R Bativala, D Crabb, D Garway-Heath, R Hitchings, S McPherson, A Tuulonen, A Viswanathan and R Wormald for their guidance and contribution to development and oversight of the study and its findings. We also thank Gladys McPherson for providing IT programming support.

Footnotes

To cite: Prior M, Burr JM, Ramsay CR, et al. Evidence base for an intervention to maximise uptake of glaucoma testing: a theory-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000710. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000710

Contributors: At the time of the research, all authors were at the University of Aberdeen Health Services Research Unit. JMB, JJF and CRR had the original ideas for the study. JJF, MP, JMB, SC and CRR developed the questionnaire. MP and SC conducted the data collection. DJ and MP performed the statistical analysis. MP drafted the paper. All authors participated in the interpretation of results, revision and approval of the final draft. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JJF is guarantor.

Funding: This study is one component of a Medical Research Council-funded strategic grant, G0701759: Developing the intervention and outcome components of a proposed randomised controlled trial of a national screening programme for open angle glaucoma. The Health Services Research Unit receives a core grant from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates. All research was conducted independent of the funders.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) MP, JMB, CRR, DJ, SC and JJF had support for the submitted work through a Medical Research Council-funded strategic grant; (2) no authors have relationships that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work and (4) no authors have non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was approved by University of Aberdeen College of Life Sciences and Medicine Ethics Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:262–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maier PC, Funk J, Schwarzer G, et al. Treatment of ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J 2005;331:134–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burr JM, Mowatt G, Hernandez R, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for open angle glaucoma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2007;11:iii–iv, ix–x, 1–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Wyatt HJ, Swanson WH, et al. Rapid pupil-based assessment of glaucomatous damage. Optom Vis Sci 2008;85:471–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant WM, Burke JF. Why do some people go blind from glaucoma? Ophthalmology 1982;89:991–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen PP. Risk and risk factors for blindness from glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2004;15:107–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safer MA, Tharps Q, Jackson TC, et al. Determinants of three Stages of delay in Seeking care at a medical Clinic. Med care 1979;17:11–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal National Institute for the Blind Open Your Eyes. London, UK: Royal National Institute for the Blind, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goddard M, Smith P. Equity of access to health care services: theory and evidence from the UK. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:1149–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross V, Shah P, Bativala R, et al. ReGAE 2: glaucoma awareness and the primary eye-care service: some perceptions among African Caribbeans in Birmingham UK. Eye (London) 2007;21:912–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UK National Screening Committee UK National Screening Committee's Policy Positions. 2009. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/criteria [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooke R, French DP. How well do the theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behaviour predict intentions and attendance at screening programmes? A meta-analysis. Psychol Health 2008;23:745–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organisational Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50:179–211 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steele DJ. Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, eds. Handbook of Psychology and Health: Social Psychological Aspects of Health. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1984:219–52 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham C, Sheeran P. Acting on intentions: the role of anticipated regret. Br J Soc Psychol 2003;42:495–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SCS Direct. 2004. http://www.scsdirect.com:8888/webcount_v2_2/index.jsp??linkname=first [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser S, Bunce C, Wormald R, et al. Deprivation and late presentation of glaucoma: case-control study. Br Med J 2001;322:639–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis JJ, Eccles MP, Johnston M, et al. Constructing Questionnaires Based on The Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Manual For Health Services Researchers. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Centre of Health Services Research, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, 2004;ISBN:0-9540161-5-7 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, et al. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosomatic Res 2006;60:631–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Figueiras MJ, Alves NC. Lay perceptions of serious illnesses: an adapted version of the Revised Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (IPQ-R) for healthy people. Psychol Health 2007;22:143–58 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burr JM, Campbell MK, Campbell SE, et al. ; Glaucoma screening Platform Study group Developing the clinical components of a complex intervention for a glaucoma screening trial: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabachnik B, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics. New York: Harper Collins, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 3rd edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol 2001;40:471–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheeran P. Intention—behavior relations: a conceptual and empirical review. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 2002;12:1–36 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, et al. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol 2008;57:660–80 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alkerwi A, Sauvageot N, Donneau A, et al. First nationwide survey on cardiovascular risk factors in Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg (ORISCAV-LUX). BMC Public Health 2010;10:468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer RC, Emmons KM, Fletcher RH, et al. Familial risk and colorectal cancer screening health beliefs and attitudes in an insured population. Prev Med 2007;45:336–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Office for National Statistics Ethnicity and Identity—Census 2001 Key Statistics. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/downloads/theme_compendia/foe2004/ethnicity.pdf (accessed 21 Sep 2011).

- 30.Taylor MF, Brice J, Buck N, et al. British Household Panel Survey User Manual Volume A: Introduction, Technical Report and Appendices. Colchester, UK: University of Essex, 2010 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.