Abstract

BACKGROUND

The lipid-laden macrophage index has been used to evaluate for gastroesophageal reflux-related respiratory disease, but the relationship between reflux detected by pH probe and the lipid-laden macrophage index is uncertain despite widespread use of the lipid-laden macrophage index in clinical decision-making. It was the aim of this study to correlate reflux as detected by multichannel intraluminal impedance with the lipid-laden macrophage index.

METHODS

Patients undergoing both pH multichannel intraluminal impedance testing and bronchoscopy between January 2002 and January 2006 were identified. Baseline characteristics were compared by using parametric and nonparametric testing. Reflux profiles were correlated with the lipid-laden macrophage index by using Spearman correlations.

RESULTS

There was no significant correlation between the lipid-laden macrophage index and the number of acid or nonacid reflux events. There also was no significant correlation between the lipid-laden macrophage index and the amount of full-column reflux. There was no significant difference between the mean lipid-laden macrophage index in patients with and without esophagitis. Finally, in patients who underwent fundoplication (n = 13) for intractable respiratory disease, there was no significant difference in any of the reflux parameters between patients who did and did not experience clinical improvement after fundoplication. There was, however, a higher lipid-laden macrophage index in patients with no symptomatic improvement compared with patients with symptomatic improvement.

CONCLUSIONS

Lipid-laden macrophage index lacks the specificity necessary to detect reflux-related respiratory disease.

Keywords: gastroesophageal reflux, pH monitoring, respiratory disease, lipid laden macrophages

Respiratory disease and gastroesophageal reflux are commonly associated; however, the cause-and-effect relationship is difficult to prove. Different techniques have been used to determine reflux-related disease, including the lipid-laden macrophage index (LLMI).1–5 The literature has suggested that values of >100 are associated with the highest risk for gastroesophageal reflux (GER)-related respiratory disease.6 Despite its mainstream use, the relationship between the LLMI and GER is uncertain,4,7,8 particularly when reflux is measured by pH-metry, which is the “gold standard” used to establish the presence of pathologic GER.9 One explanation for this lack of correlation could be that pH-metry is blind to nonacid reflux, such that reflux was occurring but was not detected by the available technology.

Recently, the advent of multichannel intraluminal impedance (pH-MIII) has allowed the detection of nonacid reflux. Recent data have suggested that nonacid reflux, as detected by pH-MII, is a significant contributor to respiratory disease.10,11 Because of these recent developments, we hypothesized that, if the LLMI is a marker of reflux-related respiratory disease, the correlation between the LLMI and acid and/or nonacid reflux should be high.

We also hypothesized that, if the LLMI is a marker of GER-related respiratory disease, patients who experience symptomatic improvement after antireflux therapy should have a significantly higher LLMI than those patients who do not experience improvement. In addition, pH-MII testing should predict which patients should have symptomatic improvement after fundoplication if the respiratory disease is GER related. This is particularly important, because fundoplication is the only therapy that treats both acid and nonacid reflux.10,12

The goal of this study was to determine whether there is a relationship between the LLMI and GER as detected by pH-MII and to determine whether there is a correlation between the LLMI and clinical response to fundoplication in children.

METHODS

All of the pH-MII studies were reviewed in patients who underwent bronchoscopy between January 2002 and August 2006. Each study was performed by using a portable pH-MII system (Sleuth, Sandhill Scientific, Denver, CO). All of the patients were admitted to Children's Hospital Boston for the 24-hour pH-MII recording. Three different, age-appropriate impedance catheters were used in the study: infant (0–2 years old), pediatric (2–10 years old), and adult (>10 years old). Impedance sensors were spaced 1.5 cm apart on the infant catheter, 2 cm apart on the pediatric catheter, and 2 to 4 cm apart on the adult catheter. Each catheter also has 1 distal pH sensor. Catheter location was confirmed by chest radiograph. The catheters were adjusted following the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines so that the pH sensor was at the third vertebral body above the diaphragmatic angle.13

Patients ate a regular diet with a minimum of 3 hours between each meal while in the hospital. Patients could not drink apple juice or soda during the study. When patients experienced symptoms or ate meals, they recorded their events on a symptom log and pushed the corresponding buttons on the recording device. Logs were reviewed by 1 of the authors (R.R.) during and at the end of the study to insure accurate completion. All of the information from the logs was manually entered into the impedance tracing. Data collected during meals were excluded from the analysis.11

The tracings were manually reviewed, and each reflux episode was scored by a single investigator (R.R.). pH monitoring analysis was done using gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) analysis software (Sandhill Scientific, Denver, CO). An acid reflux episode was defined as a drop in pH to <4 for >5 seconds. Acid clearance time was calculated as the time from a drop in pH to <4 to the time of its recovery to a pH of >4. A pH probe was considered abnormal if the pH was <4 for >6% of the time for children >1 year of age and for >12% of the time for children <1 year of age.9

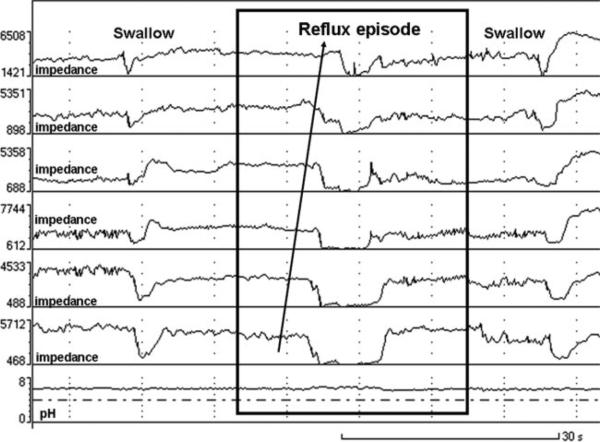

A reflux episode detected by impedance was defined as a retrograde drop in impedance to >50% of baseline in the distal 2 channels. A series of these waves defines a reflux episode. As liquid passes over the catheter from the stomach into the esophagus, the impedance drops at the distal sensor (closest to the stomach). This wave pattern progresses in a retrograde fashion up the catheter, resulting in subsequent visible drops in impedance. The bottom-most wave on an impedance tracing is a pH channel, which classifies the reflux episode as acid or nonacid (see Fig 1). Bolus clearance time was defined as the time from a drop in impedance to 50% of its baseline value to its recovery to 50% of its baseline value in the distal most impedance channel. Acid reflux episodes were those episodes detected by both pH and impedance sensors. Nonacid episodes were those episodes detected by impedance sensors only. pH-only episodes were those episodes detected by the pH sensor only and are a minimum of 5 seconds in length. Full-column reflux was defined as an episode that reached the highest pair of impedance sensors. The percentage of time that reflux is in the esophagus, as detected by impedance, was calculated by dividing the sum of the bolus clearance times by the total study duration.

FIGURE 1.

Representative picture of a nonacid reflux episode as detected by pH-MII.

Flexible bronchoscopy was performed under general anesthesia. The bronchoscope was wedged in a subsegmental bronchus (the location of which was chosen based on radiographic findings or gross findings during the examination) and 1 or 2 aliquots of 1 mL/kg of sterile normal saline instilled and suctioned for pathologic analysis. The LLMI was determined by the same pathologist based on the methods outlined by Colombo and Hallberg6; the lipid content of 100 consecutive macrophages is scored on a scale of 0 to 4 (where 0 is no opacification and 4 is completely opacified) and the scores are summed. The possible range of values is from 0 to 400.

Charts were reviewed for all of the patients who underwent a fundoplication based on clinical indications and who had also undergone pH-MII and bronchoscopy. The outcome of all of the patients after fundoplication was established without any knowledge of pH-MIII or LLMI results. Patients were reported as improved if they were able to decrease their doses of acid-blocking medicines without a worsening of respiratory status or if patients reported improvement in respiratory symptoms to their pulmonologist or gastroenterologist within 1 year of the fundoplication. Patients were excluded from analysis if they had modified barium swallows that were consistent with aspiration or if there was clinical evidence of aspiration while swallowing.

Spearman correlations were performed to determine the strength of association between continuous variables. t tests were performed to compare means. SPSS 14 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

There were 50 patients who had both bronchoscopy and pH-MII testing. The mean age of the patients was 6.4 ± 5.2 years. There were 31 male patients and 19 female patients. The primary diagnoses included asthma, recurrent pneumonia, chronic cough, chronic lung disease of unknown etiology, and other pulmonary symptoms, such as desaturations, recurrent croup, and cyanotic spells. Other patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 6.4 ± 5.2 |

| Gender, male/female ratio | 31:19 |

| Primary diagnosis, n | |

| Asthma | 12 |

| Recurrent pneumonia | 11 |

| Chronic lungd | 8 |

| Chronic lung disease | 7 |

| Other pulmonary symptoms | 12 |

| Medication during pH-MII, n | |

| None | 28 |

| H2 blocker | 1 |

| PPI | 18 |

| PPI and H2 blocker | 3 |

| Upper endoscopy (n = 23) | |

| Normal esophageal biopsies | 19 |

| Esophagitis | 4 |

H2 indicates histamine-2 receptor; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

The mean numbers of acid, nonacid, and pH-only events in the 50 patients were 22.9 ± 20.8, 20.3 ± 19.7, and 13.3 ± 17.8, respectively. The mean percentage of time that the pH was <4 was 5.9% ± 8.0%. The mean LLMI was 47.8 ± 38.5. As shown in Table 2, there were no significant correlations between the LLMI and any of the reflux parameters detected by pH-MII. There was, however, an inverse correlation between the LLMI and the percentage of time that pH was <4; the more acid present in the esophagus, the lower the LLMI.

TABLE 2.

Spearman Correlations to Determine the Relationship Between the LLMI and Reflux Parameters Detected by pH-MII

| Variable | r | P |

|---|---|---|

| No. of acid events | −0.20 | .200 |

| No. of nonacid events | −0.15 | .300 |

| No. of pH-only events | −0.18 | .200 |

| Percentage of time reflux in esophagus by pH-MII | −0.19 | .200 |

| Percentage of time pH <4 | −0.37 | .008 |

| Percentage of full-column reflux | −0.13 | .400 |

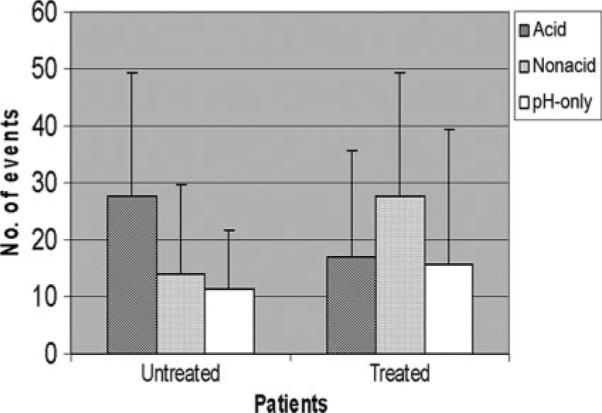

Because of the heterogeneous use of acid suppression medications, reflux profiles of patients taking acid suppression therapy were compared with profiles of patients who did not take acid suppression therapy during testing (Fig 2). In the treated patients, there were significantly more nonacid events than in untreated patients (P = .01), and there was a trend toward more acid events in untreated patients (P = .07). There were no significant differences in the mean LLMI between untreated (47.6 ± 37.0) and treated patients (48.0 ± 41.1; P = .9). There were no significant differences in the mean percentage of time that the pH was <4 between untreated (7.1% ± 9.2%) and treated patients (4.5% ± 6.1%; P = .3). Correlations between the LLMI and reflux parameters in treated and untreated patients are shown in Table 3; there was a significant inverse relationship between the LLMI and percentage of time that the pH was <4 in untreated patients.

FIGURE 2.

Reflux events in patients who were and were not taking acid-suppression medications at the time of pH-MII testing.

TABLE 3.

Spearman Correlations to Determine the Relationship Between the LLMI and Reflux Parameters in Treated and Untreated Patients

| Variable | Untreated (n = 27) |

Treated (n = 23) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| No. of acid events | −0.3 | .10 | −0.20 | .5 |

| No. of nonacid events | −0.3 | .08 | −0.02 | .9 |

| No. of pH-only events | −0.2 | .30 | −0.20 | .5 |

| Percentage of time reflux in esophagus by pH-MII | −0.5 | .20 | −0.20 | .4 |

| Percentage of time pH <4 | −0.5 | .01 | −0.30 | .2 |

We then compared the mean LLMI in patients with the presence or absence of esophagitis by esophagogastroduodenoscopy. There was no significant difference between the mean LLMI in patients with (37.0 ± 23.9) and without esophagitis (49.6 ± 39.2; P = .5). When comparing patients with and without esophagitis, there were no significant differences in any of the reflux parameters detected by pH-MII including the amount of acid or nonacid reflux (P > .05).

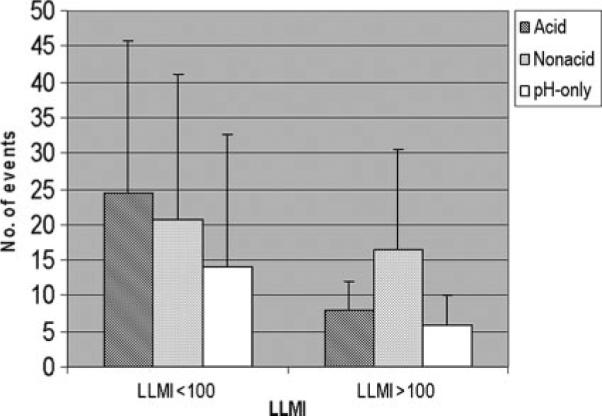

Because of the possible association with LLMI>100 and reflux disease, we compared reflux parameters between patients with an LLMI >100 (n = 5) with those with an LLMI <100 (n = 45; Fig 3); there is a higher number of acid reflux events in patients with a lower LLMI (P = .09), but there were no significant differences in any reflux parameters. There were no significant difference in the mean percentage of time that the pH was <4 between patients with an LLMI <100 (6.4% ± 8.2%) and LLMI >100 (1.5% ± 1.6%; P = .2).

FIGURE 3.

Reflux events in patients who had LLMIs of <100 and >100.

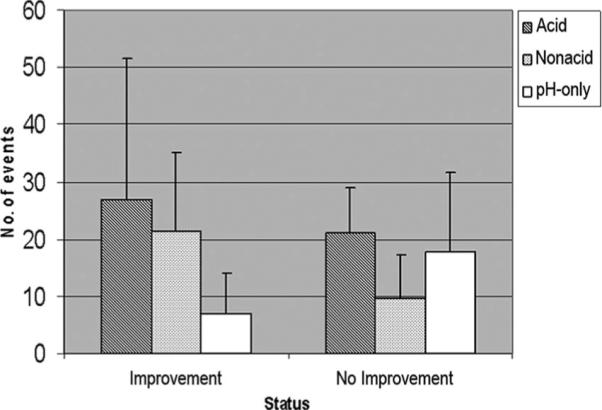

We also compared the LLMI and reflux profiles of patients who did and did not experience symptomatic improvement after fundoplication (Fig 4; P > .07). Thirteen patients underwent fundoplication, 9 of whom experienced symptomatic improvement. There were no significant differences between any of the reflux parameters between patients with and without symptomatic improvement after fundoplication. There were no significant differences in the mean LLMI between patients who were (31.6 ± 33.7) and were not improved (74.5 ± 68.3) after fundoplication (P = .15). There were no significant differences in the mean percentage of time that the pH was <4 between patients who were (5.9% ± 7.0%) and were not improved (6.9% ± 6.2%) after fundoplication (P = .8).

FIGURE 4.

Reflux events as detected by pH-MII before fundoplication in patients who did and did not experience postsurgical improvement.

Of the 4 patients who did not improve after fundoplication, 3 had a postfundoplication upper gastrointestinal series showing an intact fundoplication. One had no imaging. None had postfundoplication impedance testing. All of the fundoplications in this study were Nissen fundoplications.

DISCUSSION

The association between GER and lung disease has been well established, although the association is inconsistent.14–22 There is no gold standard to determine the causal relationship between respiratory disease and GERD. The LLMI has been adopted as an important test to determine reflux-related respiratory disease despite conflicting evidence about its utility.1,2,4–6,8 One possibility for these conflicting results may be past inability to measure nonacid reflux.

Our previous data suggested that there was a significant correlation between respiratory symptoms and nonacid reflux.11 Based on these data, we hypothesized that there would be a significant correlation between the LLMI and nonacid reflux. Our data in this study, however, show that there are no significant positive correlations between the LLMI and reflux parameters, including nonacid reflux as detected by pH-MII.

Concerned that this lack of a relationship may be a result of differing acid suppression therapies at the time of testing, we compared the reflux parameters between treated and untreated patients; we found that, whereas treated patients had significantly more nonacid reflux, there was no difference in the mean LLMI between treated and untreated patients and that the correlation between the LLMI and nonacid reflux was not stronger in treated patients. In addition, as has been seen previously in the adult literature, there was no significant difference in the total number of reflux events between treated and untreated patients; acid suppression medications shift the proportion of reflux from acid to nonacid without changing the total number of reflux events.12

We then assessed whether there was a relationship between the LLMI and other markers of reflux disease, such as esophagitis, or the percentage of time that the pH was <4 in the esophagus. Again, there was no significant relationship between reflux detected by these measures and the LLMI. These findings support what recent literature on LLMI and reflux testing suggest, that the correlation between the LLMI and GERD as detected by endoscopy and pH probe is not strong.2,8 Krishnan et al8 found that 7 of 19 patients studied with respiratory disease and positive pH probes had a positive lipid index defined by Corwin and Irwin.23 The investigators also found that 10 of 23 patients with respiratory symptoms and biopsy-proven esophagitis had a positive lipid index. Sacco et al2 studied 20 children with bronchoscopy and pH probes and found that there was a significant correlation between the LLMI (as determined by Colombo and Hallberg6) and the percentage of time that the esophageal pH was <4 but that there was no correlation between the LLMI and the number of reflux episodes >5 minutes and the number of episodes with a pH <4. Our study is the largest study of children with respiratory disease and the first to look at the relationship between LLMI and nonacid reflux, as well as the LLMI and the height of the refluxate, which can accurately be assessed by pH-MII.

Recognizing that tests for reflux are imperfect, it can be argued that the gold standard test to evaluate for GER-related respiratory disease is improvement after fundoplication. Fundoplication is the only effective method to decrease both acid and nonacid reflux. Therefore, if respiratory disease is GER related, the patient's symptoms should improve after surgery. In our series of 50 patients, 13 underwent fundoplication because of persistent respiratory symptoms and a history that was suggestive of reflux disease. Of these 13 patients, 9 had symptomatic improvement. In this population of patients who underwent fundoplication, patients who had no symptomatic improvement actually had a higher, although not statistically significant, LLMI than patients who experienced symptomatic improvement postfundoplication. This suggests that the LLMI may be a marker of lung inflammation and disease severity rather than reflux-related disease, a hypothesis that has been suggested in the adult literature.23 Furthermore, there were no significant differences between the reflux profiles, as detected by pH-MII, in these patients who did and did not experience symptomatic improvement. This suggests that pH-MII may have a limited role as a predictive, preoperative tool to diagnose GER. These data raise questions about what is the best diagnostic method to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between GER and respiratory disease and point again to the need to find better diagnostic methods.

There are some limitations to this study. First, this is a retrospective review of patients undergoing bronchoscopy and pH-MII testing, so patients were selected because their symptoms were severe enough to warrant a bronchoscopy under anesthesia. Therefore, the results may not be generalized to the population of all patients with pediatric lung disease. Second, the population of patients with respiratory disease is heterogeneous. We looked at the subpopulations (eg, treated versus untreated or with versus without esophagitis) to address this heterogeneity. Ideally, a large prospective study of patients would be able to address these limitations. Finally, patients who underwent fundoplication and had recurrence of symptoms did not undergo postfundoplication impedance testing to confirm with certainty that the fundoplication was intact. However, the upper gastrointestinal series in 3 of 4 patients showed an intact wrap. We also limited our follow-up period to the year after surgery to minimize the chance for wrap failure while insuring an adequate length of time to experience symptomatic improvement from a pulmonary or gastrointestinal perspective. Nevertheless, failure of symptomatic improvement may be a failure of the wrap.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, there is no correlation between nonacid reflux and the LLMI. There is also no significant relationship between reflux detected by endoscopy or pH probe and the LLMI. Finally, neither the LLMI nor pH-MII results predict which patients will have a better clinical response after fundoplication. These data suggest that the LLMI has limited use in predicting reflux-related respiratory disease in pediatrics and that the tools used by pediatric gastroenterologists are not sensitive enough to predict which patients have reflux-related respiratory disease.

What's Known on This Subject.

The relationship between LLMI and acid reflux is inconsistent. Recent studies show a possible relationship between nonacid reflux and respiratory symptoms. No studies have determined whether there is a relationship between the LLMI and nonacid reflux.

What This Study Adds.

There is no correlation between acid or nonacid reflux and the LLMI. We determined that the LLMI does not predict which patients improve after fundoplication, suggesting that the LLMI is a poor predictor of reflux-related respiratory disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant 1K23DK 073713-01A1.

Abbreviations

- LLMI

lipid-laden macrophage index

- GER

gastroesophageal reflux

- pH-MII

pH-multichannel intraluminal impedance

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parameswaran K, Anvari M, Efthimiadis A, Kamada D, Hargreave FE, Allen CJ. Lipid-laden macrophages in induced sputum are a marker of oropharyngeal reflux and possible gastric aspiration. Eur Respir J. 2000;16(6):1119–1122. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16f17.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacco O, Fregonese B, Silvestri M, Sabatini F, Mattioli G, Rossi GA. Bronchoalveolar lavage and esophageal pH monitoring data in children with “difficult to treat” respiratory symptoms. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;30(4):313–319. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200010)30:4<313::aid-ppul7>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang YJ, Steele CT, Anbar RD, Sinacori JT, Powers CN. Quantitation of lipid-laden macrophages in evaluation of lower airway cytology specimens from pediatric patients. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;24(2):98–103. doi: 10.1002/1097-0339(200102)24:2<98::aid-dc1018>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins KA, Geisinger KR, Wagner PH, Blackburn KS, Washburn LK, Block SM. The cytologic evaluation of lipid-laden alveolar macrophages as an indicator of aspiration pneumonia in young children. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119(3):229–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nussbaum E, Maggi JC, Mathis R, Galant SP. Association of lipid-laden alveolar macrophages and gastroesophageal reflux in children. J Pediatr. 1987;110(2):190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombo JL, Hallberg TK. Recurrent aspiration in children: lipid-laden alveolar macrophage quantitation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1987;3(2):86–89. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950030209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazachkov MY, Muhlebach MS, Livasy CA, Noah TL. Lipid-laden macrophage index and inflammation in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids in children. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(5):790–795. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00047301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan U, Mitchell JD, Tobias V, Day AS, Bohane TD. Fat laden macrophages in tracheal aspirates as a marker of reflux aspiration: a negative report. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(3):309–313. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudolph CD, Mazur LJ, Liptak GS, et al. Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32(Suppl 2):S1–S31. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200100002-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mainie I, Tutuian R, Agrawal A, et al. Fundoplication eliminates chronic cough due to non-acid reflux identified by impedance pH monitoring. Thorax. 2005;60(6):521–523. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen R, Nurko S. The importance of multichannel intraluminal impedance in the evaluation of children with persistent respiratory symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(12):2452–2458. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vela MF, Camacho-Lobato L, Srinivasan R, Tutuian R, Katz PO, Castell DO. Simultaneous intraesophageal impedance and pH measurement of acid and nonacid gastroesophageal reflux: effect of omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(7):1599–1606. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandenplas Y, Ashkenazi A, Belli D, et al. A proposition for the diagnosis and treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children: a report from a working group on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Working Group of the European Society of Paediatric Gastro-enterology and Nutrition (ESPGAN) Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152(9):704–711. doi: 10.1007/BF01953980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiljander TO, Salomaa ER, Hietanen EK, Terho EO. Gastroesophageal reflux in asthmatics: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study with omeprazole. Chest. 1999;116(5):1257–1264. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowrey DJ, Peters JH, DeMeester TR. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in asthma: effects of medical and surgical antireflux therapy on asthma control. Ann Surg. 2000;231(2):161–172. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200002000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meier JH, McNally PR, Punja M, et al. Does omeprazole (Prilosec) improve respiratory function in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux? A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39(10):2127–2133. doi: 10.1007/BF02090360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin TR, Sperling RM, McQuaid KR. Omeprazole improves peak expiratory flow rate and quality of life in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(7):1060–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.329_q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustafsson PM, Kjellman NI, Tibbling L. A trial of ranitidine in asthmatic children and adolescents with or without pathological gastro-oesophageal reflux. Eur Respir J. 1992;5(2):201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding SM, Richter JE, Guzzo MR, Schan CA, Alexander RW, Bradley LA. Asthma and gastroesophageal reflux: acid suppressive therapy improves asthma outcome. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):395–405. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leggett JJ, Johnston BT, Mills M, Gamble J, Heaney LG. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in difficult asthma: relationship to asthma outcome. Chest. 2005;127(4):1227–1231. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spechler SJ, Gordon DW, Cohen J, Williford WO, Krol W. The effects of antireflux therapy on pulmonary function in patients with severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. Department of Veterans Affairs Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(6):915–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Størdal K, Johannesdottir GB, Bentsen BS, et al. Acid suppression does not change respiratory symptoms in children with asthma and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(9):956–960. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.068890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corwin RW, Irwin RS. The lipid-laden alveolar macrophage as a marker of aspiration in parenchymal lung disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132(3):576–581. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.3.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]