Abstract

Demographic trends in the 2000s showed the continuing separation of family and household due to factors such as childbearing among single parents, the dissolution of cohabiting unions, divorce, repartnering, and remarriage. The transnational families of many immigrants also displayed this separation, as families extended across borders. In addition, demographers demonstrated during the decade that trends such as marriage and divorce were diverging according to education. Moreover, demographic trends in the age structure of the population showed that a large increase in the elderly population will occur in the 2010s. Overall, demographic trends produced an increased complexity of family life and a more ambiguous and fluid set of categories than demographers are accustomed to measuring.

Keywords: aging, cohabitation, divorce, fertility, immigration, marriage

In 1988 Paul Glick, the founder of the field of family demography, wrote the first overview of the field to appear in this journal, on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary (Glick, 1988). He organized his article around the stages of the family life cycle, a concept he had developed decades earlier (Glick, 1947). It assumed that most people experienced a linear progression from being single to getting married to having children to experiencing an empty nest and finally to death or widowhood. Glick did, to be sure, mention deviations from this path, such as single parenthood, cohabitation, divorce, and remarriage. But his assumption was that the conventional life cycle provided a useful framework for studying most Americans' family lives. It was indeed a good assumption in the middle of the twentieth century, the period from roughly 1940 to 1960, when Glick did most of his pioneering work and when most Americans moved in lockstep through the cycle. It was, however, becoming less useful by the time his review of the field appeared.

The next overview was published in 2000, the first time that an article on family demography appeared in one of the journal's decennial decade in review issues (Teachman, Tedrow, & Crowder, 2000). The authors built upon Glick's framework but gave more weight to the racial, ethnic, and social class diversity of family patterns. They paid more attention to divorce and remarriage, which had become much more common in the last decades of the century than in the middle decades; and they described the effects of economic stagnation on low income families. But they made only scant mention of cohabitation and of families extending across more than one household, in large part, they explained, because so little demographic data on these phenomena were available.

Family demographers in the 2000s moved even further away from the framework of a conventional, uniform family life cycle. For one thing, an important set of studies demonstrated a troubling divergence in the family patterns of Americans according to education and income, with several indicators moving in encouraging directions (e.g., less divorce) for the best-educated segment of the population while remaining the same or moving in discouraging directions (more divorce) for the less-educated (McLanahan, 2004). A half century ago, in contrast, most Americans, rich or poor, lived in two parent families that in many ways were similar. The result is that Americans with different levels of education now tend to follow different paths through family formation and dissolution. This divergence is likely to remain a major focus of demographic research in the 2010s.

It remains unclear why this divergence is occurring, although it is tempting to associate it with trends in the labor market. Since the 1970s, the globalization and automation of production have reduced the labor market opportunities of individuals without college degrees, whereas the opportunities for those with college degrees may have increased, or at least not declined as much. Perhaps as a result, the wages of men without college degrees have fallen since the early 1970s, and the wages of women without college degrees have failed to grow (Ellwood & Jencks, 2004; Richer et al, 2003). By 1996, the average 30-year-old man with a high school degree earned 20% less than a comparable man in 1979 (Levy, 1998). Moreover, it still seems to be a prerequisite for marriage that a prospective husband have the ability to earn a decent, stable income. So it may be that labor market trends are discouraging marriage (and increasing marital dissolution) among the less educated, while the college educated marry each other and consolidate the gains they have made in the restructured American economy. Nevertheless, this explanation is speculative; research in the 2010s hopefully will provide a better understanding of what has produced this demographic gap.

Also inconsistent with the family life cycle framework is the continuing separation of family and household, which has progressed further than when Teachman, Tedrow and Crowder (2000) mentioned it briefly ten years ago. This separation has accelerated not just because of divorce and nonmarital childbearing but also because of childbearing in fragile cohabiting unions and because of new phenomena such as the growth of transnational immigrant families. The themes of the diverging family patterns and the separation of family and household will be interwoven with this review of research on demographic trends in the 2000s. I also will highlight an area of family demography that developed rather quietly during the decade but which will, I am confident, become a much more visible topic in the 2010s: the aging of the population and its implications for family life.

Marriage

The typical age at marriage continued its decades-long rise in the 2000s: the median age at first marriage rose to 27.4 for men and 25.6 for women in 2008 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2009). Racial and ethnic differentials persisted: According to one widely cited set of life table estimates, 81% of non-Hispanic White women, 77% of Hispanic women, and 52% of non-Hispanic African American women were predicted to marry by age 30 (Bramlett and Mosher, 2002). In addition, the college educated are more likely to ever marry than are the less educated (Goldstein & Kenney, 2001), but they delay marrying more than do other groups. Fewer of them marry before age 25, in large part because they are finishing their education or starting careers. In their late 20s and 30s, however, their marriage rates are greater than the rates for individuals with less education (Martin, 2004); and by the time they have reached their forties, they are more likely to have ever married. Early in the transition to adulthood, in other words, women who will go on to obtain college degrees look as though they will have a lower probability of marrying than other women; but by their thirties they prove to have a higher probability.

Moreover, who one marries depends on one's education more so than in the past. In the early twentieth century, one's religion was of greater significance for choosing a spouse than it is today. A college educated Protestant was more likely to marry a Protestant high school graduate than to marry a college educated Catholic. Yet since then college graduates have become more likely to marry each other than to marry individuals of the same religion but without college degrees. Although religion still matters, college graduates have largely separated themselves from the rest of the marriage market (Kalmijn, 1991). And people without high school degrees have become more isolated at the other end of the marriage market: they are less likely to marry individuals with more education than they have (Schwartz & Mare, 2005). What seems to be occurring is that the marriage market is settling into three submarkets : one for the college educated, one for the least educated, and one for those with a high school degree and perhaps a few years of college.

Divorce

The aggregate risk of a marriage ending in divorce appears to have declined from the peak that occurred about 1980. Perhaps half of marriages that were begun around that time will end in divorce, but the lifetime level of divorce may not be as high for marriages begun recently. The exact predicted percentage depends on whether one includes separations (the vast majority of which are permanent) and on what data source and analytical technique one uses. Nearly all studies suggest that the lifetime probability of disruption is between 40% and 50% (Raley & Bumpass, 2003; Schoen & Standish, 2001; Stevenson & Wolfers, 2007; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2005).

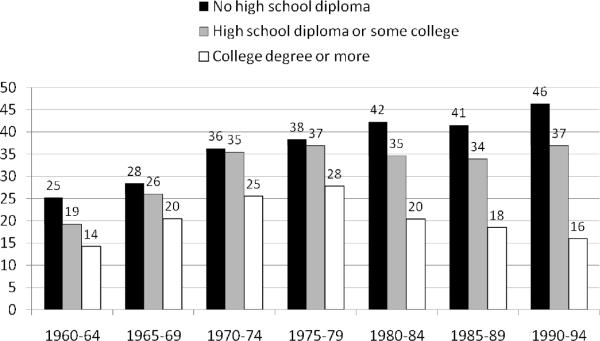

Like marriage rates, divorce rates are diverging by education. During the 1960s and 1970s, the probability that a marriage would end in divorce rose sharply for all groups (Cherlin, 1992). Since then, however the probability of divorce has declined among married couples in which the spouses have college degrees, while divorce probabilities have stayed roughly the same or even increased for the less educated. Figure 1from Martin (2006) illustrates this trend over the 20-year period, 1975 to 1994, using retrospective reports by women in the 1996 and 2001 Surveys of Income and Program Participation. It displays the proportion of marriages that ended in a permanent separation or divorce during the first 10 years of the marriage, by five-year marriage cohorts. Although at all times women with college degrees have a lower probability of separation or divorce, the gap is much wider among all women who married in the 1990 to 1994 period than it is among all women who married in the 1970 to 1974 period. The figure shows that during the 1960s and 1970s, the probability of permanent separation or divorce was rising for all women who were entering marriage. Since then, there has been a substantial decrease for women with college degrees, whereas the probability has continued to increase among women without high school degrees and has held roughly constant among women with a high school degree or some college. Raley and Bumpass (2003) reported similar findings for the dissolution of all unions (whether marital or cohabiting) during the period of 1980 to 1994: the probability of dissolution increased for all educational groups except those with college degrees, among whom the probability remained unchanged.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Women With a Permanent Separation or Divorce within Ten Years of a First Marriage: Life Table Estimates by Educational Level (Martin, 2006).

(Few demographic analyses of trends in remarriage were published in the 2000s, so it is not known whether it became more or less common among the divorced population. Past studies had suggested that remarriage rates were declining but that the formation of cohabiting unions among the previously married was compensating for most of the decline [Bumpass, Sweet, & Cherlin, 1991].)

Fertility

In a journal published in almost any other nation, a review of recent demographic research would feature the birth rate as a major topic. In large part the lesser attention to births among Americans is a reflection of the relatively high level of fertility in the United States compared to other developed countries. In 2006, the total fertility rate, the expected number of children that a woman would give birth to during her lifetime, was 2.10, which is the level that would be required to replace the population (U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, 2009a). The American total fertility rate was boosted by the fertility of Hispanic women, whose total fertility rate was 2.89. (Non-Hispanic African American women had a total fertility rate of 2.11, which matched the national average. Moreover, as will be discussed below, the high total fertility rate of Hispanics is largely driven by the fertility of Mexican-origin women.) Yet even among non-Hispanic White women, the total fertility rate was 1.86, which was similar to the highest levels of fertility to be found in Europe, such as Sweden (1.85) or the United Kingdom (1.85). (Institut National d'Études Démographiques, 2008). This level of fertility, combined with the high levels of immigration to the United States, blunts any concern about declining population size. Consistent with this outlook, most fertility research in the United States in the 2000s focused not on fertility trends per se but rather on fertility in a particular context: nonmarital fertility, fertility among adolescents, or fertility and immigration.

In 1950 only 4% of all children were born outside of marriage; by 2007, in comparison, 39.7% of all children were born outside of marriage (U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, 2005, 2009b). In the mid-to-late twentieth century, many researchers focused on a rise in childbearing among unmarried adolescents. But by the mid-2000s, teenage birth rates had dropped to levels not seen in two decades (U.S. National Center for Health Statistics 2000, 2009a) before rising again slightly toward the end of the decade. Whereas in 1970 teenagers accounted for 50% of all nonmarital births, by 1999 they accounted for only 29% (U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, 2000). In contrast, births to unmarried women in their twenties rose sharply because women were postponing marriage but not postponing having children as much. By the mid 2000s, the birth rates for unmarried women in their twenties far exceeded the birth rates for unmarried teens (U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, 2009a).

This rise among unmarried women in their twenties and thirties has occurred mainly among women without college degrees. Childbearing outside of marriage has remained uncommon among college educated women, who still tend to follow the conventional pathway: finish one's education, then marry, then have children. But childbearing outside of marriage has become much more common among less-educated women in their twenties or thirties. In the period from 1997 to 2001, 93% of women with a college degree who gave birth were married, compared to 71% of women with some college, 57% of women with a high school degree, and 39% of women without a high school degree (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008). Less-educated and low income women and men are increasingly having children prior to marrying. Women from neighborhoods where few lasting marriages are visible perceive little cost to taking this path (Edin & Kefalas, 2005).

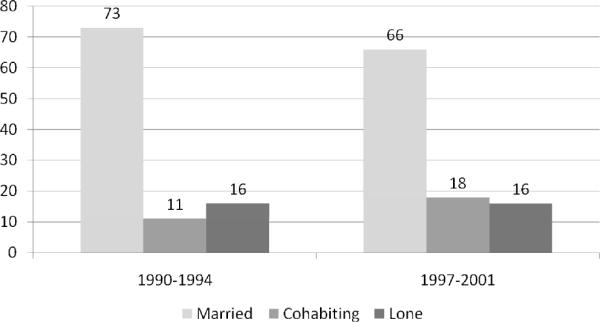

Although 39.7% of all births in the United States now occur to unmarried women, not all of them occur to unpartnered unmarried women. Americans still use the term “single parents” to describe unmarried parents, as if the only possible statuses were to be married or to be without a partner. This was true a half century ago when cohabitation was very uncommon. Until the 1990s, government statistics still followed this practice by ignoring the possibility that single parents may have cohabiting partners present. Yet many supposedly single parents are indeed cohabiting; the best estimate is that about half of unmarried women who give birth are cohabiting with the fathers of their children (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008). Moreover, a large share of the increase in nonmarital childbearing since the 1990s has occurred to cohabiting couples. Figure 2, drawn from Kennedy and Bumpass (2008) shows the trend for the 1990s: The proportion of children born to married mothers declined during the decade, but the proportion of children born to lone (i.e., neither married nor cohabiting) mothers remained constant at 16%. Only the proportion born to cohabiting mothers increased, going from 11% to 18%. Cohabitation has become an important context for childbearing.

Figure 2.

Mother's Union Status at Birth, Children Born 1997–2001 and 1990–1994 (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008).

Several studies published during the decade addressed the growing number of adults who have children with more than one partner, a situation that was labeled “multiple partner fertility” or “multi-partnered fertility.” One source of multiple partner fertility is the high rate of union dissolution in the United States. Over 20% of married couples separate or divorce within 5 years of marrying, and among couples who start their relationship by cohabiting, over 50% end their union within 5 years, whether they marry in the interim or not (Andersson & Philipov, 2002). These are much higher rates than in nearly all other Western countries. For instance, about 10% of Canadian and 12% of German married couples separate or divorce within 5 years (Andersson & Philipov, 2002; Statistics Canada, 1997). About 29% of French and 37% of Swedish cohabiting couples disrupt within 5 years (Andersson & Philipov, 2002).

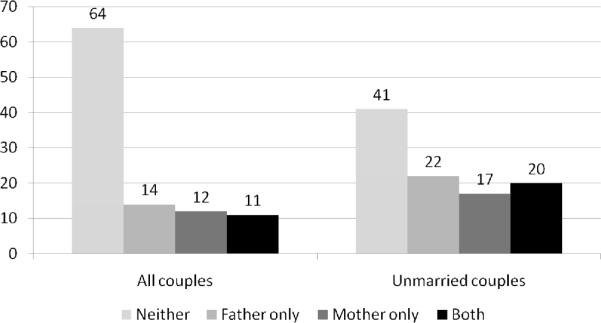

Parents who give birth to a child outside of marriage are much more likely to have children with a second (and subsequent) partner than are women who give birth while married. This difference can be seen from Figure 3, which is adopted from Carlson & Furstenberg (2006). Using data on the Fragile Families sample of urban births to couples in 1998 to 2000 (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel & McLanahan, 2001), they show that among all couples giving birth, one or both parents had a child by another partner in 36% of the cases (see left panel), whereas among just the unmarried couples, one or both had a child by another partner in 59% of the cases (right panel). In fact, both parents already had a child by a previous partner in 20% of the births to unmarried couples. Thus, multiple partner fertility is already quite common in the United States.

Figure 3.

Percentage of Urban Births to Couples in which Fathers or Mothers had Previous Children by Other Partners, 1998 – 2000, by marital status (Carlson & Furstenberg, 2006).

Studies of multiple partner fertility are just beginning; we should know much more about this phenomenon 10 years from now. In terms of the demography of multiple partner fertility, research suggests that it is more common among mothers who had their first children at an early age, who were African American, and who attended religious services less often (Carlson & Furstenberg, 2006; Guzzo & Furstenberg, 2007). Women who had children with multiple partners were less likely, according to one study, to say that they had family or friends they could count on for social support, such as a small loan or a place to stay – although whether the lack of support is a cause or an effect of multiple partner fertility is unclear (Harknett & Knab, 2007). According to a study in Wisconsin, a majority of mothers receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the main cash welfare program, had children with more than one father (Meyer, Cancian, & Cook, 2005). Beyond these rudimentary demographic differences, however, we have little understanding of how the obvious complexity that multiple partner fertility introduces into family life plays out in the daily lives of the parents and children who are involved.

Cohabitation

Cohabitation continued to become more widespread, according to research published in the 2000s. As has been the case ever since cohabitation became common several decades ago, people with less education are more likely to cohabit. But cohabitation has become common among all educational groups. According to data on women age 19 to 44 in the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, nearly two thirds of those with a high school degree or less education had ever cohabited. Among those with some college education but no four-year degree, nearly half had cohabited, and among those with four-year degrees, 45% had cohabited (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008). In addition, Americans' cohabiting unions have a shorter duration than in most other Western countries: A set of comparable surveys conducted in the mid-1990s showed that the median duration of a cohabiting union for a never-married woman in the United States was 14 months – the shortest of 11 countries. In comparison the median duration was 27 months in Germany, 40 months in Canada, and 51 months in France (Heuveline & Timberlake, 2004).

Even cohabiting couples with children tend to cohabit for a short period before marrying or ending their relationships. A five-year follow-up study of the Fragile Families sample of urban births found that 26% of the couples who were cohabiting at birth had married, 48% were no longer living together, and 26% were still cohabiting (Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing, 2007). Thus, about half of the urban children experienced the breakup of their parents' cohabiting relationship by their fifth birthday. Other studies also suggest that children born to cohabiting parents have a high risk of seeing their parents' relationship end. Nationally, according to 2002 data, about 50% of children born to cohabiting parents experienced the disruption of the marriage by age nine, compared to about 20% of children born to married parents (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008).

The substantial number of cohabiting parents suggests that cohabitation has become a diverse phenomenon. Demographic research in the 2000s turned to examining this diversity. Although many people still have an image of cohabiting couples as childless people living together before marrying, 39% of all the opposite-sex couples in the 2007 Current Population Survey who identified as unmarried partners had at least one biological child of either partner present (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008a). Unmarried partners (whether they had children or not) tended to be young: 45% of the women and 38% of the men were under 30. Yet noticeable numbers were older: 33% of the women and 38% of the men were age 40 or older; and 3.3% of the women and 4.6% of the men were 65 years old or over (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008a).

During the 2000s qualitative researchers attempted to understand how cohabiting relationships start and what they mean to the couples involved. One study of working- and lower-middle-class young adults in the Toledo, Ohio, area who were cohabiting or had recently done so found that entry into cohabitation sometimes occurred as a gradual process without a clear decision to live together: a partner might stay over one night per week, then three or four, and then seven without much discussion of the nature of their developing relationship, a phenomenon the researchers called a “slide” or a “drift” into cohabitation (Manning & Smock, 2005). This finding suggests that demographic surveys that ask for a date at which a person began to cohabit may get answers that are approximate rather than precise. Moreover, the researchers found that when a decision is made to cohabit, the issue often has little to do with whether to marry or not, at least initially, but rather it centers on whether to cohabit or remain single (Manning & Smock, 2005). Similarly, interviews with 25 cohabitors in the New York City area, most of whom had attended college, showed that few thought of their relationships as trial marriages when they started them (Sassler, 2004).

But even if marriage is not foremost in the minds of cohabitors initially, most will either marry their partners or break up with them relatively soon. Data from 2002 show that 32% of women's premarital cohabiting unions end with a marriage within two years, and 24% end in a breakup; all in all, more than half end within 2 years (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008). Among poor women, cohabiting unions last somewhat longer and are less likely to end in marriage, than among nonpoor women (Lichter, Qian, & Mellott, 2006). So even if most couples are not thinking about marriage at first, they are likely to formalize their relationship through a wedding if they wish to stay together more than a few years.

Same-Sex Unions

The data on cohabitation that I have considered to this point are only for opposite-sex couples. For lesbians and gay men cohabitation remains the only form of partnership available except in states where same-sex marriage is legal, which at this writing included Connecticut, Iowa, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Prior to 1990 there were no federal data on same-sex couples. The 2000 Census counted 594,391 same-sex cohabiting couples based on (1) same-sex individuals who reported themselves to be “unmarried partners” plus (2) married couples in which both partners were reported to be of the same sex (and whom the Census Bureau counted as if they were same-sex cohabiting couples who had reported themselves as married) (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2003c). This tabulation probably missed some same-sex cohabiting unions whose members did not report themselves as unmarried partners, and it probably misclassified some opposite-sex married couples who reported their sex incorrectly (O'Connell & Gooding, 2007). With these caveats, the 2000 Census found that children were commonly present in same-sex cohabiting unions: 33% of women in same-sex partnerships and 22% of men in same-sex partnerships had children living with them.

Several surveys were conducted in the 2000s in California during which people were asked their sexual orientation, unlike Census Bureau surveys. The California surveys show that 37% to 46%, depending on the survey, of gay men were cohabiting with a partner, as were 51% to 62% of lesbians (Carpenter & Gates, 2008). By comparison, 62% of heterosexuals with comparable ages were either cohabiting or married. So nearly as many lesbians in California were partnered as were heterosexual women. Cohabitation was common among gay men, but they were less likely to be partnered than were heterosexual men. Partnered lesbians were also more likely to have children present in their households (14% to 31%, depending on the survey) than were partnered gay men (3% to 5%). The figures for gay men are substantially lower than the percentages with children reported by the Census Bureau. Researchers in the 2010s will have much room for improvement in studying the demography of gay and lesbian families, particularly now that same-sex marriage is legal in some states.

Children's Living Arrangements

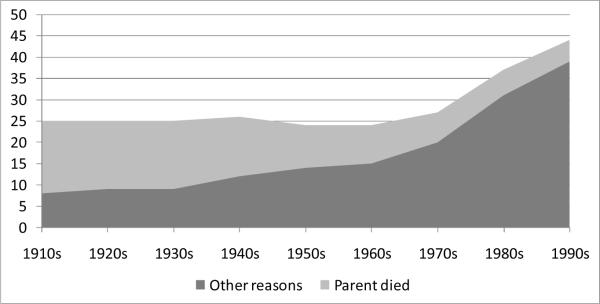

As a result of high levels of divorce, the dissolution of cohabiting relationships in which children are present, and the increase in childbearing among unpartnered adults, children are much more likely to have a parent living elsewhere than in the past. Correspondingly, adults are much more likely to have children living elsewhere. Figure 4 shows the trend during the twentieth century in the percentage of children who were not living with both biological parents, taken from Ellwood and Jencks (2004). It is based on the retrospective answers of adults in the General Social Survey to the question of whether they were living with both parents at age 16. During the first half of the century, there was little change: about 25% of children, according to these recollections, were not living with both parents. Early in the century, most of the missing parents had died, and only a small minority were missing for “other reasons” (predominantly divorce or separation). From that point through the 1950s, declining adult death rates diminished the percentage of children losing a parent through death, but rising levels of divorce and separation increased just enough to leave the overall percentage not living with both parents largely unchanged. In fact, in the 1950s, the percentage not living with both parents dipped to a century-wide low. The divorce rate stood at perhaps one in three marriages (Cherlin, 1992), which was well below the nearly one-in-two level of the current era, while death rates continued to decline. As a result, the nuclear family of husband, wife, and children, which was predominant in the first half of the century, reached its zenith in the 1950s. This trend allowed observers to assume a close correspondence between family and household. It allowed the Census Bureau to knock on the doors of households and find, for the most part, self-sufficient families. It simplified the task of counting families, but more profoundly it simplified the task of thinking about families.

Figure 4.

U.S. Children Not Living with Own Mother and Father at age 16 Because a Parent Died or For Other Reasons, 1910s to 1990s (Ellwood & Jencks, 2004)

Starting in the 1960s, however, levels of divorce, separation, and childbearing outside of marriage rose much faster than death rates fell, so that the overall percentage of children not living with both parents rose sharply. And unlike similar children a century ago, most of the children who were not living with both parents had one of them living elsewhere. If these children had contact with their nonresident parents, their families could be said to extend across two households. If a new partner of the resident parent had moved in, that person might have ties to children in yet another household. It might be the case that two children in a household had different nonresidential parents. A foster child in the same household might have both biological parents living elsewhere. In addition, since about 1980 the propensity of children to live with both parents has fallen for a new and distressing reason: a massive increase in incarceration, particularly of African Americans (Pettit & Western, 2004). One in four African American children born in 1990 had a parent imprisoned by the time they were age 14; the corresponding figure for White children was one in 25 (Wildeman, 2009). In all these ways, the correspondence between family and household had weakened by the end of the century.

Moreover, the growing number of cohabiting unions, the increase in childbearing among cohabiting partners, and the high (if declining somewhat) levels of divorce have created a situation in which more individuals experience multiple marital and cohabiting partnerships during their adult lives; and more children experience multiple partnerships of their parents while growing up. Children born to cohabiting couples, for instance, are at least twice as likely to see their parents separate as are children whose parents are married at the time of their birth (Heuveline, Timberlake, & Furstenberg, 2003). Comparative data from the Fertility and Family Surveys, done in the 1990s, show that American children were much more likely to experience 2 or 3 parental partnerships by age 15 than were children in other Western nations (Cherlin, 2009). Building on pioneering studies in the 1990s (e.g., Wu & Martinson, 1993), a number of researchers have been examining the consequences for children of experiencing multiple parental transitions in spouses and cohabiting partners, independent of the amount of time they have spent living with a single parent. They find that the number of transitions that children experience is associated with undesirable outcomes such as behavior problems (Fomby & Cherlin, 2007, Osborne & McLanahan, 2007) and less competency in interacting with peers at school (Cavanagh & Huston, 2006). It is not clear how much of this association is causal rather than reflecting underlying, unmeasured factors. And if it is causal, the precise mechanisms are not well understood. The researchers typically hypothesize that frequent transitions cause greater family stress, which affects children; but the evidence base is still thin. Nor do we have satisfactory demographic estimates of the current prevalence of this phenomenon.

Living Apart Together

Families are extending across households in other ways that challenge our understanding of what a family is. Consider couples who are in cohabitation- or marriage-like relationships, who define themselves as couples, but who live in separate households. This arrangement has become known as “living apart together.” In 1996 and 1998, the General Social Survey asked a sample of Americans this question if they were not married: “Do you have a main romantic involvement – a (man/woman) you think of as a steady, a lover, a partner, or whatever?” And if they said yes, they were asked if they lived with that partner. Seven percent of women and 6% of men age 23 and older said that they had a partner but did not live with that person (Strohm, Seltzer, Cochran, & Mays, 2009).

Reports from national statistical agencies in Britain, Canada, and France suggest that living-apart-together relationships are relatively common, but they also suggest how difficult it is to conceptualize and measure the phenomenon. In 2002 and 2003, the British agency asked the following question of people in national samples who were not married or cohabiting: “Do you currently have a regular partner?” After excluding people still living in their parents' homes and full-time students, the report's author found that about 15% of all individuals who were not cohabiting or married responded “yes” and therefore could be considered “living apart together”(Haskey, 2005). Statistics Canada used the question, “Are you in an intimate relationship with someone who lives in a separate household?” and reported that 8% of all Canadians 20 and over, and 56% of all Canadians in their twenties, said yes (Milan & Peters, 2003). A 2005 French survey asked those who were not married or cohabiting, “Are you currently having a stable, intimate relationship with someone you're not living with?” and found that 10 percent of all men and 11 percent of all women aged 18 to 79 who had a partner could be classified as living apart together (Régnier-Loilier, Beaujouan, & Villeneuve-Gokalp, 2009). Yet all of these questions may be so broad that they capture conventional steady relationships as well as mature separate-residence partnerships. Over the next decade, improvements will be needed in how to define and measure these relationships.

Early Adulthood

Another way in which family and household are separating is in the rising number of unmarried and unpartnered young adults who are heading their own households rather than still living in their parents' homes. After remaining near 5% for the first half of the twentieth century, the percentage of 20 to 29 year-old unmarried individuals who were heading their own households rose sharply in the second half of the century to 36% for women and 28% for men in 2000 (Rosenfeld, 2007). These young adults, along with a growing number in their thirties, had not completed all the transitions that typically defined adulthood (and which have long been thought to include marriage and childbearing), and yet they were living independently, often completing their education, and in many cases working. Researchers in the 2000s, examining this shift, began to write about a new life stage that is occurring between adolescence and full adulthood, which they called early adulthood (Settersten, Furstenberg, & Rumbaut, 2005). It can extend through one's twenties and into one's thirties. The main factor in the emergence of this life stage is education. Because employment opportunities have improved more for the college educated, young adults are staying in school longer to complete college or graduate degrees. Whereas it was unusual for a 24-year-old to still be in college in the early 1990s, today perhaps 1 out of 6 Whites and 1 out of 8 African Americans of that age are enrolled at least part time (Fussell & Furstenberg, 2005). These early adults are likely to postpone decisions about careers and families, although they may cohabit with a partner. For individuals who do not attend college, the idea of a distinct life stage of early adulthood is less useful. This is another area in which scholarship will likely be developed in the next decade.

Immigration

For most of the 2000s, immigration continued at the near-record levels of the late twentieth century, although the recession late in the decade slowed the flow. By 2006, the foreign born constituted 12.1% of the American population (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008c), the highest percentage since the early decades of the twentieth century (Brown & Bean, 2005). The ethnic composition of the immigrant population continued to be heavily Hispanic and Asian, and among Hispanics, Mexicans continued to constitute the largest nationality group. During the decade of the 2000s, Hispanics overtook African Americans as the largest minority group in the United States (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008c).

Until recently, the study of immigration was largely restricted to studying male immigrants, reflecting a distant past in which heavily-male European and Asian populations immigrated in search of opportunity. For that reason, much of the past demographic research on immigration did not focus on family life. That is, however, no longer the case. The foreign-born population of the United States has been relatively equally split between women and men since the mid-twentieth century (Tyree & Donato, 1985). In 2003, 50% of the population age 18 and over that were counted as foreign-born in the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey were women (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2004). Some of the foreign-born women entered the United States as the spouses of immigrants already in the country under the family reunification provisions of immigration law, but others entered in search of work. In the 1990s and even more so in the 2000s, a small literature has emerged on women who have immigrated to the United States, some legally and some not, to take jobs as caregivers to American children or as house cleaners (Ehrenreich & Hochschild, 2002; Hondagnau-Sotelo & Avila,1997; Parreñas, 2001). What is notable about this group from a family perspective is that many of them have left their own children in their home countries to take caregiving jobs in the United States. They try to stay in touch through telephones and the Internet, and they send back a large share of their earnings to their families at home. These “transnational families” have been studied by sociologists and others in the growing field of “care work” studies (England, 2005). This phenomenon raises issues for family studies such as the net benefit to children worldwide of the movement of mothers from the less-wealthy sending countries to the wealthier receiving countries – what Ehrenreich and Hochschild (2003) referred to as a “care drain” from the sending countries.

During the decade of the 2000s, progress also was made in unpacking the category of Hispanic. In prior decades, the literature on Hispanic family life in the United States had emphasized the role of culture, specifically familism. This concept, about which there has been much debate, connotes a commitment to family expressed through strong relationships with nuclear and extended family members and through a relatively high number of married-couple households. It has been the dominant cultural explanation for the high rates of marriage among Hispanics despite their poor economic standing (Landale, Oropesa, & Bradatan, 2006). As scholars have shown, however, the concept of a marriage-centered familism applies to Hispanics of Mexican and Cuban origin more than to Hispanics of Puerto Rican or Dominican origin; and among Mexicans it applies more to first-generation immigrants than to the second or third generation (Oropesa & Landale, 2004). For instance, scholars have noted that family life in Mexico is more patriarchal and more focused on marriage than is the case in much of the Caribbean. Demographers and sociologists have long written about the “paradox of Mexican nuptiality:” the tendency of Americans of Mexican origin to marry at similar rates than non-Hispanic Whites, despite their lower economic standing (Oropesa, Lichter, & Anderson, 1994). It now appears that this difference is driven by recent immigrants. They have high rates of marriage; but Americans of Mexican origin who were born in the United States tend to marry at similar ages as do non-Hispanic Whites (Raley, Durden, & Wildsmith, 2004).

Still, family life among Mexican-origin Americans, as well as Cuban Americans, is more focused on marriage than is family life among those of other Caribbean origin such as Puerto Ricans and Dominicans. For instance, Lichter and Qian (2004) showed that two-parent, single-earner families are more common among Mexican American families than among other Hispanics. Eighteen percent of Mexican family households were headed by a woman (Landale et al., 2006). Moreover, Mexicans tend to have more children than most other nationality groups. The total fertility rate was 3.06 for Mexican-origin Americans in 2005, compared to 2.14 for Puerto Ricans, and 1.58 for Cubans (U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, 2009a). Here again, fertility was lower for native-born Americans of Mexican origin than for immigrants from Mexico. Still, immigration from Mexico is greatly affecting the size of the American population. According to one estimate, Mexican immigrants and their descendants since the 1980s will have produced 36 million births by 2040 (Johnson & Rendall, 2004).

At the other end of the spectrum of Hispanic immigration, those from the Dominican Republic bring with them a family culture that is characterized as matrifocal, whereas Puerto Ricans are in the middle of this continuum (Massey, Fischer, & Capoferro, 2006). Forty-two percent of Dominican family households in the United States were headed by woman, according to pooled data from the 1998 to 2002 Current Population Survey, a figure that is identical to the figure of 42% for non-Hispanic African Americans and somewhat above the 34% figure for Puerto Ricans (Landale, et al., 2006). (The comparable figure for non-Hispanic Whites is 11%.) Demographic research in the next decade should retain the focus on the diversity of the Hispanic ethnic category (and expand it to the diverse Asian category).

Aging

Demographic research on aging during the decade was spurred by concern about the difficulties that may emerge in the decade of the 2010s as the large baby boom generation enters retirement. They are enjoying longer life expectancies and better health than past generations, and they remain a source of support to children and grandchildren. At the same time, their entry into old age may soon create a shortage of caregivers for the frail older population, adding to the responsibilities of adult children and to the financial burdens of workers who pay Social Security and Medicare taxes. As a result of these developments, intergenerational bonds of parents, children, and grandchildren have become increasingly important and potentially problematic.

The percentage of the population that is age 65 or older, which is the conventional definition of old age, has been rising in all developed nations and many developing ones. This rise can occur over time for two reasons: the proportion of older people in the population can increase due to greater longevity or the proportion of children can decrease due to a decline in the birth rate. Both have occurred, but the latter factor – the sharp decline in births – has been the dominant factor in the recent experience of most countries. In Japan, where the birth rate fell quickly after World War II and has remained low, 21% of the population was 65 or older in the late 2000s, the highest percentage of any country. In central and southern Europe, where birth rates are extremely low (a little over one birth per woman, on average) the proportion of the population that is age 65 or older is nearly as high: 20% in Italy and 19% in Germany (Population Reference Bureau, 2007). This trend has received less attention in the United States because its relatively high birth rate (a total fertility rate over 2.0, as noted earlier) and large number of immigrants have moderated the aging of the population: 12% of Americans were 65 or over in the late 2000s (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008c).

But over the next two decades, the percentage of older Americans will rise sharply to a projected 16% in 2020 and 19% in 2030 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008b). The reason is that the baby boom generation – people who were born during the very high birth rate years between 1945 and 1965 – will begin to enter old age in 2010. When they were in midlife, they had far fewer children than their parents. As they enter their retirement years, then, they will be large in numbers compared to middle-aged working people. Today there are about 5 working-age adults (18 to 64) for every older person. In 2020 there will be a 4 per older person, and in 2030 there will be 3 per older person (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008b). As this transition occurs, the implications of an aging population will become a more common theme of American social scientific research on the family, and the existing research literature will become more widely read and cited.

In fact, the aging of the population has a number of important implications for family life, as researchers have recently noted (Waite, 2009). It will increase the importance of vertical kinship ties, up and down the generations, relative to the horizontal kinship ties of adults to spouses, partners, brothers, and sisters (Bengtson, 2001). Intergenerational relations involving grandparents, their children, and their grandchildren will play a larger role in family life. Although people tend to assume that the flow of support is upward from adult children to their older parents, the reality is that until late in old age, parents provide more assistance to adult children and grandchildren than they receive (Agree & Glaser, 2009). Demographers have shown that the period of old age in which individuals are relatively healthy, and therefore better equipped to provide support, has increased in recent decades. For instance, one study found that the proportion of the older population with moderate disabilities (e.g., difficulty doing housework or shopping) declined from 16% in 1984 to 12% in 2004–2005; and the percentage with severe disabilities (e.g., difficulty getting out of bed by oneself) declined from 10% to 7% over the same period (Manton, Gu, & Lamb, 2006a). Researchers now speak of “active life expectancy:” the number of years that a person can expect to live beyond age 65 without disabilities; it has increased from 11 years in 1965 to a projected 15 or 16 years in 2015 (Manton, Gu, & Lamb, 2006b) The rise appears to be due to advances in medical care, higher standards of living, and greater education (Schoeni, Freedman, & Martin, 2008).

As a result, we would expect to see more support from grandparents to their children and grandchildren than in the past, and that is what some recent studies have shown. In part, this increase is due to the great numbers of adult daughters who are working outside the home and who rely on grandparents for child care. In 2005, grandparents were the primary care providers for 20.5% of the preschool-aged children whose mothers were employed (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008d). More broadly, the percentage of grandparents who have partial or full responsibility for caring for grandchildren is substantial. Of the 5.8 million grandparents in the 2000 Census who lived with their grandchildren, 42% responded that they were “currently responsible for most of the basic needs of one or more of these grandchildren.” The percentage rose to 52% among African American grandparents and 56% among American Indians and Alaska natives. Furthermore, in one third of the families with grandparent caregivers, the middle, parent generation was absent from the household – perhaps due to incarceration, illness, or substance abuse. In these so-called “skipped-generation” households, grandparents have full responsibility for their grandchildren. Households headed by caregiving grandparents tended to be poorer than other households (U.S Bureau of the Census, 2003b). Although caregiving can be a rewarding experience for all concerned, it can be physically and financially difficult for an older adult to take over the parenting of a grandchild.

When older persons need care themselves, how will recent demographic trends affect the likelihood that they will receive it? Family members still do most of the care of frail older people (Agree & Glaser, 2009); so the changes in family patterns in recent decades – the higher level of divorce than at midcentury, the proportion of children born outside of marriage, the increase in childbearing among cohabiting partners, and the rise in multiple-partner fertility – may influence care. All of these changes have created a greater degree of complexity in family life. These complexities mean that an older person may have an expanded network of kin and quasi-kin that may include current and former partners, stepchildren, children born outside of marriage and raised by an ex-partner, half siblings, and so forth. The average size of the kin networks of older Americans is likely to increase as these complex patterns become more common (Wachter, 1997). Theoretically, this increase could expand the pool of potential caregivers. However, it is unclear how people related to each other through complex ties view their obligations to each other. The basic problem for intergenerational caregiving is that these complex patterns could be creating family networks in which there are more and more people whom one may count as kin but in which one owes less and less to each of them (Ganong and Coleman, 1999; Bianchi et al., 2008). With few exceptions, lasting kin relationships depend not on biological or legal ties but rather on the work that one does in forging and maintaining ties or, conversely, letting them lapse (Carsten, 2004). One does the work of kinship by providing assistance to a child in another household – or one does little and the relationship withers. Lines of assistance and obligation are ambiguous and depend on continuing contact and exchange. Under this situation, it is unclear who will lend assistance to an older person who is in need of it. The problem is greater for older men than for older women because they tend not to have lived with children from past marriages or relationships (Lin, 2008). They may also not have a partner who feels obligated to help them. One ethnographic study of older low-income adults found men who, in their fifties or sixties and in poor health with nowhere to go, showed up at the doors of ex-girlfriends or ex-wives and asked to be taken in (Newman, 2003). While demographic trends in longevity, active life expectancy, and births have received less attention in the United States than in other developed countries in the 2000s, the attention paid to these trends by researchers and policy makers is likely to increase in the 2010s.

Conclusion

Family scholars have long monitored demographic trends to understand how the structure of family life is changing. They have pondered the implications of changes in such concrete indicators as births, deaths, marriages, and divorces. Demographic indicators have been regarded as hard rather than soft statistics – easy to measure, transparent in meaning, and clear in interpretation. Today, some indicators retain these qualities. It is still useful to know how the total fertility rate varies among racial and ethnic groups and how it compares to other wealthy countries. The age structure of the population provides a clear, reliable picture of the size of the older population in the next few decades. Differences in rates of marriage and divorce can be enlightening. Yet other demographic indicators have been losing their clarity. We can still count the number of immigrants who enter the United States legally, but we have less success in counting the large undocumented immigrant population. Nor do our immigration statistics account for movements back and forth across borders.

More problematic is that traditional demographic indicators are becoming less useful in identifying the units we call families. To be sure, the family unit is still clear and nonproblematic for many people, but for a significant minority it is becoming increasingly difficult to tell where the boundaries of a family unit lie. The old demographic assumption that household-based surveys could capture families has been undermined by social changes such as childbearing outside of marriage and higher levels of divorce and remarriage. In addition, advances in communication and transportation allow immigrant families to extend not just over more than one household but also over more than one country. The new limitations of traditional demography challenge family scholars to rethink what the concept of a family means and how to measure it. Some iconoclasts suggest that the idea of a family may be outdated (Roseneil & Budgeon, 2004). Although most family researchers would reject this position, they are being prodded to explain what a family is and why the concept is still useful. These are not questions that demographers alone can answer. Rather they require the involvement of the larger family research community.

The difficulty, in part, is that family demographers have developed techniques that are good at measuring events with clear beginnings, endings, and boundaries; but the phenomena they study increasingly fail to have these nice properties. Cohabiting relationships may not have a clear beginning point. Single parents and their adolescents often disagree on whether new, seemingly cohabiting partners are part of the family (Brown & Manning, 2009). The cross-household ties that multiple partner fertility can create may lead to families without clear boundaries. These situations call not just for revised measures but also for revised concepts and methods.

In particular, family demographers may need to rethink the types of statistical models they use to represent family life. All of the current models assume that we can know with certainty who is in a household and who is not, who has ties to kin living elsewhere and who does not, who is in a cohabiting relationship and who is not, and so forth. We believe that one can learn the definitive answers to these questions by including standard batteries of questions in survey instruments. Increasingly, however, questions such as these cannot be answered with certainty, even by respondents who are trying to do so. A woman whose boyfriend is currently spending four nights per week at her apartment may not know whether she is really in a cohabiting relationship, or she may think so but her partner may not. A man may say he has regular contact with his children living elsewhere but may drift in and out of their lives, depending on whether he has the money to pay child support. Whether or not a man is a stepfather may depend not just on whether he is living with a mother and her children from previous relationships but also on how much time and effort he invests in his relationships with the children.

In situations such as these, estimating the probability that a person occupies a particular category (cohabiting partner, stepparent) rather than the certainty that a person is or is not in the category may be the best we can do. We may need to consider a number of pieces of information to determine if someone is cohabiting or is a stepparent (nights spent in the home, where one's clothes are kept, relationships with former or other current partners, activities with children in the household, etc.); and then we may need to combine them into a statistical model of the probability of being in the status in question. These probabilistic estimates would sometimes replace the assumed binary categories (e.g., stepfather or not) that we use in our models. In other words, we might make statements such as, “individual A is cohabiting with a probability of 0.7.” In some circumstances, probabilistic estimates would also be applied to contact and exchange among the generations. For instance, we may not be able to know with certainty whether an older man would receive assistance from his adult stepchildren if a need arises in the near future, even if we ask him about it directly. Rather, we may only be able to piece together a probabilistic statement of the likelihood that he will receive assistance. The resulting models would necessarily be more complex and would draw on the mathematics of probability theory and stochastic processes. The closest analog today would be models in which multiple indicators are used to model latent constructs, which are then used to estimate structural models – the so-called LISREL (linear structural relations) models of sociology and developmental psychology or the MIMIC (multiple indicators and multiple causes) models of economics.

Even so, probabilistic mathematics is unlikely to be sufficient. We will also need to draw upon qualitative, ethnographic studies that can suggest what the best indicators of being in a particular status are and, more fundamentally, whether there are emerging statuses (e.g., living apart together) that we should begin to model. It may seem discouraging to give up the idea that we can know for sure whether someone is in a particular family status, but other disciplines have learned to cope with constraints such as these. For nearly a century, physicists have accepted that under some circumstances they cannot determine with certainty the position of a subatomic particle. They have learned to live with probabilistic statements, and indeed they have thrived. Demographic researchers in the years ahead might do well to follow their example.

References

- Agree EM, Glaser K. Demography of informal caregiving. In: Uhlenberg P, editor. International handbook of population aging. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 647–668. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Philipov D. Life-table representations of family dynamics in Sweden, Hungary, and 14 others FFS countries: a project of descriptions of demographic behavior. Demographic Research. 2002;7:67–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bendheim-Thoman Center for Child Wellbeing Parents' relationship status five years after a nonmarital birth. Fragile Families Research Brief. 2007 Retrieved December 6, 2008, from http://www.fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/briefs/ResearchBrief39.pdf.

- Bengtson VL. Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Hotz VJ, McGarry K, Seltzer J. Intergenerational ties: theories, trends, and challenges. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Bianchi S, Seltzer J, editors. Intergenerational caregiving. Urban Institute Press; Washington, DC: 2008. pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Binstock G, Thornton A. Separations, reconciliations, and living apart in cohabiting and marital unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:432–443. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce and remarriage in the United States”, Series 22, No 2. 2002 Retrieved May 5, 2009, from www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_022.pdf. [PubMed]

- Brown SK, Bean FD. International migration. In: Poston DL, Micklin M, editors. Handbook of population. Kluwer; New York: 2005. pp. 347–382. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Manning WD. Family boundary ambiguity and the measurement of family structure. Demography. 2009;46:85–101. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Sweet JA, Cherlin AJ. The Role of Cohabitation in Declining Rates of Marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:338–355. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, Furstenberg FF., Jr. The prevalence and correlates of multipartnered fertility among urban U.S. Parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:718–732. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C, Gates GJ. Gay and lesbian partnership: evidence from California. Demography. 2008;45:573–590. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carsten J. After kinship. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE, Huston AC. Family instability and children's early problem behavior. Social Forces. 2006;85:551–581. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Marriage, divorce, remarriage. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in America today. Alfred A. Knopf; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas MJ. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich B, Hochschild A. Global woman: Nannies, maids, and sex workers in the new economy. Metropolitan Books; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood DT, Jencks C. The uneven spread of single-parent families: What do we know? Where do we look for answers? In: Neckerman KM, editor. Social inequality. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2004. pp. 3–118. [Google Scholar]

- England P. Emerging theories of care work. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, Cherlin AJ. Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review. 2007;72:181–204. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E, Furstenburg FF., Jr. The transition to adulthood during the twentieth century. In: Settersten RA Jr., Furstenburg FF Jr., Rumbaut R, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2005. pp. 29–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ganong LH, Coleman M. Stepfamily relationships: Development, dynamics, and interventions. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Glick PC. The family cycle. American Sociological Review. 1947;12:164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Glick PC. Fifty years of family demography: A record of social change. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:861–873. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR, Kenney CT. Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. Women. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB, Furstenberg FF. Multipartnered fertility among young women with a nonmarital first birth: Prevalence and risk factors. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2007;39:29–38. doi: 10.1363/3902907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harknett K, Knab J. More kin, less support: Multipartnered fertility and perceived support among mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Haskey J. Living arrangements in contemporary Britain: Having a partner who usually lives elsewhere and living apart together (LAT) Population Trends. 2005;122(winter):35–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, Timberlake JM. The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:1214–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, Timberlake JM, Furstenberg FF., Jr. Shifting childrearing to single Mothers: Results from 17 Western Countries. Population and Development Review. 2003;29:47–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondagnau-Sotelo P, Avila E. “I'm here, but I'm there”: The meanings of Latina transnational motherhood. Gender & Society. 1997;11:548–571. [Google Scholar]

- Institut National d'Études Démographiques Total fertility (mean number of live births per woman) 2008 Retrieved December 4, 2008, from http://www.ined.fr/en/pop_figures/developed_countries/total_fertility/

- Johnson SH, Rendall MS. The Fertility Contribution of Mexican immigration to the United States. Demography. 2004;41:129–150. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. Shifting boundaries: Trends in religious and educational homogamy. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:786–800. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Bumpass L. Cohabitation and children's living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1663–1692. doi: 10.4054/demres.2008.19.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa R, Bradatan C. Hispanic families in the United States: Family structure and process in an era of family change. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the future of America. 2006. pp. 138–178. [Google Scholar]

- Levy F. The new dollars and dreams: American incomes and economic change. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Qian Z. Marriage and family in a multiracial society (The American people: Census 2000) Russell Sage Foundation and Population Reference Bureau; New York and Washington: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Qian Z, Mellott LM. Marriage or dissolution? Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography. 2006;43:223–240. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin IF. Consequences of parental divorce for adult children's support of their frail parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(1):113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ. Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG, Gu XL, Lamb VL. Change in chronic disability from 1982 to 2004/2005 as measured by long-term changes in function and health in the US elderly population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006a;103(48):18374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608483103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG, Gu XL, Lamb VL. Long-term trends in life expectancy and active life expectancy in the United States. Population and Development Review. 2006b;32(1):81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP. Women's education and family timing: outcomes and trends associated with age at marriage and first birth. In: Neckerman KM, editor. Social inequality. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2004. pp. 79–118. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP. Trends in marital dissolution by women's education in the United States. Demographic Research. 2006;15:537–560. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Fischer MJ, Capoferro C. International migration and gender in Latin America: A comparative analysis. International Migration. 2006;44(5):63–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2006.00387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography. 2004;41:607–627. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer DR, Cancian M, Cook ST. Multiple-partner fertility: Incidence and implications for child support policy. Social Service Review. 2005;79:577–601. [Google Scholar]

- Milan A, Peters A. Couples living apart. Canadian Social Trends. 2003 summer;:2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Newman KS. A different shade of gray: Midlife and beyond in the inner city. The New Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell M, Gooding G. Editing unmarried couples in Census Bureau data. 2007 Retrieved December 2, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps07/twps07.pdf.

- Oropesa RS, Landale NS. The future of marriage and Hispanics. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:901–920. [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa RS, Lichter DT, Anderson RN. Marriage markets and the paradox of Mexican American nuptiality. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56(4):889–907. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, McLanahan S. Partnership instability and child well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Parreñas RS. Mothering from a distance: Emotions, gender, and intergenerational relations in Filipino transnational families. Feminist Studies. 2001;27:361–390. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau World population data sheet. 2007 Retrieved August 14, 2008, from http://www.prb.org/pdf07/07WPDS_Eng.pdf.

- Raley RK, Bumpass LL. The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research. 2003;8:245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Durden TE, Wildsmith E. Understanding Mexican-American marriage patterns using a life-course approach. Social Science Quarterly. 2004;85:872–890. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS. Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23:303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Régnier-Loilier A, Beaujouan E, Villeneuve-Gokalp C. Neither single, nor in a couple: A study of living apart together in France. Demographic Research. 2009;21:75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Richer E, Frank A, Greenberg M, Savner S, Turetsky V. Boom times a bust: declining employment among less-educated young men. 2003 Retrieved December 4, 2008, from http://www.clasp.org/publications/Boom_Times.pdf.

- Roseneil S, Budgeon S. Cultures of intimacy and care beyond “the family”: Personal life and social change in the early 21st century. Current Sociology. 2004;52:135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MJ. The age of independence: Interracial Unions, same-sex unions, and the changing American family. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Safa H. The Matrifocal family and patriarchal ideology in Cuba and the Caribbean. Journal of Latin American Anthropology. 2005;10(2):314–338. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S. The process of entry into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen R, Standish N. The retrenchment of marriage: results from marital status life tables for the United States, 1995. Population and Development Review. 2001;27:553–563. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni RF, Freedman VA, Martin LG. Why is late-life disability declining? The Milbank Quarterly. 2008;86(1):47–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CR, Mare RD. Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography. 2005;42:621–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA Jr., Furstenberg FF Jr., Rumbaut RG, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . Common-law unions in Canada at the end of the 20th century (No. 91-209-XPE) Ottawa: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Wolfers J. Trends in marital stability. 2007 Retrieved December 6, 2008, from http://bpp.wharton.upenn.edu/betseys/papers/Trends%20in%20Marital%20Stability.pdf.

- Strohm CQ, Seltzer JA, Cochran SD, Mays VM. “Living apart together” relationships in the United States. Demographic Research. 2009;21:177–214. doi: 10.4054/demres.2009.21.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman JD, Tedrow LM, Crowder KD. The changing demography of America's families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1234–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Tyree A, Donato KM. The sex composition of legal immigrants to the United States. Sociology and Social Research. 1985;69:577–584. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census The foreign-born population: 2000. 2003a Retrieved September 11, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-34.pdf.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census Grandparents living with grandchildren: 2000. 2003b Retrieved 3 July, 2005, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-31.pdf.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census . Married-couple and unmarried-partner households: 2000. (Census 2000 Special Reports, CENSR-5) U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2003c. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census Table 2.1 Foreign-born population by sex, age, and year of entry: 2003. 2004 Retrieved September 11, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/foreign/ppl-174.html.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces, 2001. 2005 Retrieved December 6, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2005pubs/p70-97.pdf.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census America's families and living arrangement: 2007. Table UC4. Opposite Sex unmarried couples. 2008a Retrieved November 29, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam/cps2007.html.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census Percent distribution of the projected population by selected age groups and sex for the United States: 2010 to 2050 (NP2008-T3) 2008b Retrieved August 15, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/summarytables.html.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census Statistical abstract of the united states, 2008. 2008c Retrieved November 15, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/

- U.S. Bureau of the Census Table 2B: Primary child care arrangements of preschoolers under 5 years old living with employed mothers by selected characteristics: Spring 2005. 2008d Retrieved August 21, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/child/ppl-2005/tab02B.xls.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census Table MS-2. Estimated median age at first marriage, by sex: 1890 to the present. Families and Living Arrangements. 2009 Retrieved May 5, 2009, from http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/ms2.xls.

- U.S. National Center for Health Statistics Nonmarital childbearing in the United States, 1940–1999. National vital statistics reports, vol. 48, no. 16. 2000 Retrieved February 4, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr48/nvs48_16.pdf. [PubMed]

- U.S. National Center for Health Statistics Number and percent of births to unmarried women, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 1940–2000. 2005 Retrieved December 3, 2005, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statab/t001x17.pdf.

- U.S. National Center for Health Statistics Births: final data for 2006. National vital statistics reports, vol. 57, no. 7. 2009a Retrieved May 5, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_07.pdf.

- U.S. National Center for Health Statistics Changing patterns of nonmarital childbearing in the United States. Data brief no. 18. 2009b Retrieved May 14, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db18.pdf. [PubMed]

- Wachter K. Kinship Resources for the Elderly. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 1997;352:1811–1817. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ. The changing family and aging populations. Population and Development Review. 2009;35:341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C. Parental imprisonment, the prison boom, and the concentration of childhood disadvantage. Demography. 2009;46:265–280. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL, Martinson BC. Family Structure and the risk of premarital birth. American Sociological Review. 1993;59:210–232. [Google Scholar]