Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated the feasibility and efficacy of a working memory training program for improving memory and language skills in a sample of 9 children who are deaf (age 7–15 years) with cochlear implants (CIs).

Method

All children completed the Cogmed Working Memory Training program on a home computer over a 5-week period. Feasibility and acceptability of the program were evaluated using parent report and measures of children’s performance on the training exercises. Efficacy measures of working memory and sentence repetition were obtained prior to training, immediately after training, and 1 month and 6 months after training.

Results

Children’s performance improved on most training exercises, and parents reported no problems with children’s hearing or understanding of the exercises. After completion of working memory training, children demonstrated significant improvement on measures of verbal and nonverbal working memory, parent-reported working memory behavior, and sentence-repetition skills. The magnitude of improvement in working memory decreased slightly at the 1-month follow-up and more substantially at 6-month follow-up. However, sentence repetition continued to show marked improvement at 6-month follow-up.

Conclusions

Working memory training may produce benefit for some memory and language skills for children with CIs, supporting the importance of conducting a large-scale, randomized clinical trial with this population.

Keywords: cochlear implants, deafness, memory, language

Neurocognitive functions, ranging from basic sensory processes to higher-order thinking, are highly integrated and interdependent for their development throughout the lifespan (Luria, 1973). For example, sensory experiences such as sound and auditory input provide building blocks not only for speech and language but also for cognitive functions such as sequencing abilities and memory skills (Conway, Pisoni, & Kronenberger, 2009). Speech and language skills, particularly internalized speech and verbal mediation, enhance the development of reasoning skills, self-control, memory, and executive functioning (Barkley, 1997; Vygotsky, 1934). Because of this interdependence of sensory experience and cognitive development, conditions that affect or alter sensory input may have secondary influences on higher-order, seemingly unrelated cognitive functions (see Luria, 1973).

Conditions that involve absent or degraded auditory input, such as deafness and hearing impairment, are associated with differences (relative to normal-hearing controls) on several types of cognitive tasks (Ullman & Pierpont, 2005). Skills such as visual attention and visual–perceptual memory, for example, are enhanced in samples of deaf individuals (Bavelier, Dye, & Hauser, 2006; Blair, 1957), whereas visual span and sequential memory have been found to be below average relative to norms (Blair, 1957). Other research has identified deficits in some areas of executive functioning (inhibition, planning, set-shifting, and some types of attention) in samples of individuals with hearing impairment, possibly mediated by weaknesses in speech-language functioning (Figueras, Edwards, & Langdon, 2008; Pisoni, Conway, Kronenberger, Henning, & Anaya, 2010).

Cochlear implants (CIs) restore some components of hearing to children who are deaf, resulting in the development of speech and language skills in many cases. However, an early period of deafness, followed by limitations in auditory input from CIs, has an ongoing impact on speech-language and other neurocognitive development in many children with CIs. As a result, a wide variety of speech perception, speech production, and language outcomes are seen in the CI population, with some children achieving near-normal functioning in quiet listening conditions yet others struggling with basic speech-language abilities (Pisoni et al., 2008). Furthermore, auditory sensory deprivation associated with deafness (and, later, with degraded sound input from the CI) may also affect neurocognitive development in ways that go well beyond speech and language functioning. For example, children with CIs may have more problems in some areas of executive functioning (including planning, inhibition, set-shifting, and working memory) than children with normal hearing (Beer, Pisoni, & Kronenberger, 2009; Figueras et al., 2008; Pisoni et al., 2010). On average, CI users score below age norms on measures of auditory working memory (Pisoni & Cleary, 2003; Pisoni et al., 2008), and the speed of their retrieval of correctly recalled spoken digits from auditory short-term memory is three times slower than that of normal-hearing children (Burkholder & Pisoni, 2003). The visual memory spans and some visual sequencing skills of individuals with CIs also fall below average compared with normal-hearing controls (Cleary, Pisoni, & Geers, 2001; Conway et al., 2009; Pisoni & Cleary, 2004).

Research supports a link between some of these “at-risk” areas of neurocognitive functioning and the development of speech and language skills in children with CIs. This finding is especially important because speech-language outcomes in children with CIs are not fully explained by conventional device, demographic, and audiological measures (Geers, Brenner, & Davidson, 2003). Some of this unexplained variance in speech-language outcomes may be a result of differences in core underlying neurocognitive functions that provide the foundation for the development of speech and language skills. In particular, working memory skills have been found to correlate with the development of speech-language abilities in children with CIs (Pisoni, Kronenberger, Roman, & Geers, in press).

Working memory is defined as the ability to encode, store, and manipulate information concurrently with other mental processing activities (Baddeley, 2007). Baddeley (2007) proposed one of the most widely used and accepted models of working memory (although other models of working memory exist; see Cowan, 2005; Engle, Tuholski, Laughlin, & Conway, 1999), conceptualizing working memory as consisting of a phonological loop (rote, passive storage of verbal information); visuospatial sketchpad (passive storage of visual and spatial information); central executive (active memory system that regulates and coordinates the passive elements of the working memory system as well as closely related cognitive functions such as attention and allocation of mental resources); and episodic buffer (subsystem that accesses long-term memory information to integrate with new working memory information). Activities of the central executive, combined with the passive storage functions of the phonological loop and/or visuospatial sketchpad, are most often conceptualized as working memory because the central executive is required to simultaneously manage concurrent memory information and other cognitive activities. However, rote memory activity involving phonological information or visual–spatial information also accesses working memory components (phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad, respectively), although such rote memory tasks are often conceptualized as “short-term” or “immediate” memory tasks in order to differentiate them from tasks that are more demanding on the central executive (St. Clair-Thompson, 2010). Nevertheless, assessment of all three of these components (central executive, phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad) is important for fully conceptualizing the key components of working memory (Pickering & Gathercole, 2001). For example, a digit span forward task or spatial span forward task, which require only rote reproduction of a sequence with no manipulation, may be considered to reflect more short-term memory processes and fewer working memory (e.g., activity of the central executive) processes. Conversely, tasks that require manipulation of information simultaneous with memory activity (such as recall of digits or spatial locations in backward order) put a larger burden on the central executive and therefore would be considered to reflect a more narrow or classic definition of working memory (see Pickering & Gathercole, 2001).

Working memory is critical for cognitive information processing because it acts as a short-term mental “workbench” for information that is the focus of immediate attention and controlled processing (Baddeley, 2003, 2007). The volume and quality of information that can be held in working memory constrain what the individual has available for use during a wide range of cognitive tasks, including speech perception and language learning. Therefore, working memory is critical for speech and language development, and growth in working memory skills is closely linked to improvement in language skills with age (Pickering & Gathercole, 2001; Pisoni et al., 2010).

CI users with longer verbal working memory spans demonstrate better performance on a range of spokenword recognition tasks (Geers et al., 2003; Pisoni & Geers, 2000). Cleary, Pisoni, and Kirk (2002) showed strong relationships between forward digit span (emphasizing the phonological loop component of working memory) and open-set word recognition skills in children with CIs. Spoken-word recognition and receptive vocabulary scores were also found to be strongly associated with reproductive memory span for sequences of lights and sounds (Cleary et al., 2002). Pisoni et al. (in press) found that verbal working memory abilities in early childhood strongly predicted a wide variety of speech and language skills—including spoken-word recognition, sentence repetition, vocabulary, reading, and nonword repetition—in children with CIs 8 years later.

Sentence repetition (the ability to repeat spoken sentences; sometimes referred to as sentence recall, sentence memory, or sentence imitation; Archibald & Joanisse, 2009) may be the best example of a core speech-language skill that is both strongly related to working memory and at risk in children with CIs. Sentence repetition is especially difficult for children with CIs, and performance on sentence-repetition tasks correlates with performance on other measures of speech perception in CI samples (Geers et al., 2003). Sentence-repetition tasks involve components of working memory, speech perception, and linguistic and sequencing skills and are better clinical markers of specific language impairment than more basic speech-language tasks such as nonword repetition (Archibald & Joanisse, 2009; Conti-Ramsden, Botting, & Faragher, 2001; Stokes, Wong, Fletcher, & Leonard, 2006). Children with CIs score below normal-hearing peers even on measures of sentence perception that place minimal demands on repetition and working memory skills (Figueras et al., 2008), indicating that working memory alone does not explain the difficulty of sentence-repetition tasks for children with CIs.

Hence, children with CIs are at risk for compromised development of working memory skills, which may be one of the core underlying neurocognitive factors that can help to explain the large variability in speech-language outcomes observed in the CI population. Working memory may affect language skills by setting fundamental limits on the capacity of language and related information that can be processed, as well as by influencing the efficiency with which new information is encoded and stored. This effect may be most pronounced for language skills that involve a component of working memory, such as sentence-repetition skills. In addition to being important for development of speech and language, working memory is also critical for other areas of neurocognitive functioning and behavioral adaptation, including attention, concentration, learning, executive functioning, and behavioral self-control (Barkley, 1997). Interventions designed to improve working memory capacity may therefore enhance some selective areas of speech-language development such as sentence-repetition skills as well as provide additional benefits for cognitive development in children with CIs.

Several novel, computer-based training programs to improve working memory have demonstrated promise in normal-hearing samples of children with impairment in executive functioning, attention, and/or working memory. Klingberg et al. (2005) documented significant improvement on measures of attention, concentration, and memory in a blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) who completed a 5-week working memory training program, with gains maintained at 3-month follow-up. Similar results were reported by Holmes, Gathercole, and Dunning (2009) in a blinded, placebo-controlled study using children with normal hearing who have low working memory skills. In another study of 25 children with ADHD, Holmes, Gathercole, Place, et al. (2009) found significant improvement in verbal and nonverbal working memory following working memory training, over and above working memory improvements shown with psychostimulant medication.

These studies of working memory training were conducted using a program originally designed for children with normal hearing. Furthermore, much of the focus in training working memory in children with ADHD has been on visual working memory (which is hypothesized to be more affected than verbal working memory in ADHD) as opposed to auditory–verbal working memory and language skills (Holmes, Gathercole, Place, et al., 2009; Klingberg et al., 2005). Hence, these new behaviorally based interventions may hold promise for improving working memory in children with CIs, but several questions must be addressed first: Are existing working memory training programs (which were developed for children with normal hearing) appropriate, feasible, and acceptable for children with CIs? Can a working memory training program produce improvement in working memory and other neurocognitive skills in children with CIs, beyond the trained tasks in the program alone? Finally, can a working memory training program produce improvements in speech and language skills that generalize and transfer beyond the specific training conditions?

We sought to address these three basic questions in a pilot study of the feasibility and efficacy of a widely researched working memory training program (Cogmed Working Memory Training) in a sample of children with CIs. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of a behaviorally based training program targeted at a core neurocognitive ability other than speech and language in the CI population. The primary goal of this study was to provide information about whether improvement in a key speech-language skill, sentence repetition—which is particularly at risk in the CI population—might be achieved by remediating a hypothesized underlying neurocognitive weakness in working memory capacity in a sample of children who are deaf and who wear CIs.

Method

Participants

Participants for the study were nine children (ages 7–15 years; M = 10.2 years, SD = 2.2; six girls, three boys; eight White, one Asian) who were recruited using a database of families whose children had received CIs at a large university-based teaching hospital and who had consented to be contacted for potential participation in research studies. Participants were required to have severe or profound bilateral hearing loss from birth (mean unaided pure-tone average for the frequencies 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz = 107.4 dB HL; SD = 10.1) and cochlear implantation prior to age 3 years (M = 20.8 months, SD = 6.8). Participants were from English-speaking home environments with current or past enrollment in a rehabilitative program that encouraged the development of spoken language and listening skills. Participants were also required to have average or below average working memory skills based on testing at the first study visit, as shown by either (a) a Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning (BRIEF; Gioia, Isquith, Guy, & Kenworthy, 2000) Working Memory T-score of 50 or higher or (b) a Children’s Memory Scale (CMS; Cohen, 1997) Numbers (Digit Span) scaled score of 10 or lower.

Procedure

Study Visits

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the university institutional review board, and all study visits took place at the hospital-based CI clinic. Participants attended an initial screening visit, followed by a 2- to 5-week waiting period during which no intervention took place. At the end of the waiting period, participants returned for a pretraining visit, which was followed by a 5-week training period during which all participants completed the standard Cogmed Working Memory Training (Klingberg et al., 2005) at home. At the end of the training period, participants returned for a posttraining visit. At 1 month and 6 months after completion of the training period, participants returned for follow-up visits. Participants were paid $75 for each study visit and $25 per week of Cogmed training to offset expenses and inconvenience.

Cogmed Working Memory Training

The Cogmed Working Memory Training program (Klingberg et al., 2005) consists of 12 different kinds of video game–like, computer-based exercises that require the user to complete tasks involving auditory, visuospatial, or combined auditory–visuospatial short-term and working memory skills. Participants completed the Cogmed exercises at home for approximately 30–40 min per day, 5 days per week, during a 5-week training period. Therefore, a complete course of Cogmed training was 25 training days, and each training day consisted of eight exercises selected from among the 12 different Cogmed exercises. During the 25 days of training, each exercise was presented to the child as few as five times (for the “Decoder” exercise, which requires participants to remember a sequence of letters) or as many as 25 times (several exercises) based on a standard training schedule developed by Cogmed. With the exception of Decoder, all other exercises were administered 10 times or more during the 25 training days. A minimum of 20 completed Cogmed training days was required to remain in the study.

The Cogmed program uses an adaptive training algorithm that presents users with problems of increasing difficulty (span length and complexity) at a level slightly higher than that at which they have recently achieved success. The Cogmed program was introduced, explained, and demonstrated to participants and parents at the pretraining visit, and families then installed and ran the program on their home computers. Parents were encouraged to closely monitor their child during completion of the Cogmed exercises at home and to reward their child for completing daily and weekly exercises. Information about participants’ use of and performance on the program was sent to the password-protected Cogmed Internet site that was accessed by the research team in order to monitor each participant’s progress with the program. Participants and parents received a weekly phone call from study personnel (Cogmed-certified coaches), who reviewed program progress, assisted with problems, and encouraged continued adherence to the program.

Measures

At each study visit, participants and parents completed a battery of tests evaluating program feasibility and acceptability, working memory skills, and speech-language skills. Performance-based tests of working memory and speech-language skills were administered individually by experienced speech-language pathologists with expertise in evaluation of children with CIs. In order to reduce practice effects on working memory tests, versions with different item content were used at different visits.

Feasibility and Acceptability Measures

Cogmed performance

An initial step in evaluating the appropriateness of the Cogmed program for children with CIs involved establishing that participants could show improvement on the working memory training exercises. In order to evaluate this type of improvement, a performance improvement value was obtained for each of the 12 Cogmed exercises by subtracting the mean training level on the third day for the exercise (the third day was used as a baseline score in order to allow the child’s performance to stabilize) from the mean training level for the child’s best performance in the final 5 days of the exercise. The mean training level is roughly based on the average number of units (e.g., span length of words, numbers, or locations, depending on the exercise) presented to the child during a training day for that exercise; for example, on a spatial location exercise, a mean training level of 4 on a particular day would indicate that the child was presented with, on average, four locations to remember per item for that exercise on that day. Because the Cogmed program uses an adaptive training algorithm, the number of units (span length) presented directly corresponds to the number of units that the child is able to remember correctly. Thus, the exercise-specific performance improvement value reflected improvement in memory units remembered for that exercise between the beginning and end of the 5-week Cogmed training.

Program Feasibility Questionnaire

Parent ratings of the feasibility and acceptability of the program were evaluated with the Program Feasibility Questionnaire (PFQ; see Table 1), a 15-item measure designed to assess the challenges, problems, and satisfaction with the working memory training program. Parents rated each item on a 5-point scale of agreement (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). The PFQ was completed at the posttraining visit.

Table 1.

Feasibility and acceptability of Cogmed at posttraining (Program Feasibility Questionnaire).

| Item | M | % Agree | % Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Difficult to do during first week | 2.33 | 33 | 67 |

| 2. Difficult to do during last week | 3.78 | 78 | 22 |

| 3. Difficulty hearing exercises | 1.89 | 0 | 89 |

| 4. Difficulty understanding auditory exercises | 1.56 | 0 | 89 |

| 5. Difficulty understanding visual exercises | 1.44 | 0 | 89 |

| 6. Difficulty motivating child during first week | 1.67 | 0 | 78 |

| 7. Difficulty motivating child during last week | 4.00 | 78 | 22 |

| 8. Child’s attention improved after Cogmed | 3.44 | 44 | 0 |

| 9. Child’s memory improved after Cogmed | 3.44 | 44 | 0 |

| 10. Child’s learning ability improved after Cogmed | 3.11 | 22 | 11 |

| 11. Child’s language improved after Cogmed | 2.67 | 0 | 33 |

| 12. Happy with results of Cogmed | 3.44 | 56 | 11 |

| 13. A lot of child effort required for Cogmed | 4.00 | 78 | 11 |

| 14. A lot of parent effort required for Cogmed | 3.44 | 67 | 33 |

| 15. Would recommend Cogmed to others with CIs | 3.78 | 67 | 0 |

Note. Rating scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree. Mean ratings > 3 suggest that the sample agreed, on average, with the statement; mean ratings < 3 indicate that the sample disagreed, on average, with the statement. % Agree indicates percentage of the sample providing ratings of 4 (agree) or 5 (strongly agree); % Disagree indicates percentage of the sample providing ratings of 2 (disagree) or 1 (strongly disagree). Percentages may not add to 100% because ratings of 3 (neutral) are not counted in percentages.

Working Memory Efficacy Measures

Digit span

Participants completed a standard auditory digit span measure at each study visit, consisting of a Digits Forward subtest (repetition of a series of spoken digits in forward order, beginning with a span length of two digits and progressing until two series at the same span length were repeated incorrectly) and a Digits Backward subtest (identical to Digits Forward except that the series of digits must be repeated in backward order). At the screening visit, the Numbers subtest of the CMS (Cohen, 1997) was used for instructions and items in order to provide comparison to normative data (scaled scores); for the pretraining, posttraining, and 1-month follow-up visits, the same task and instructions were used, but different items (digit lists) were presented to participants. Items for the digit lists used for these three visits were generated randomly (following the same rules governing the CMS Numbers lists—namely, that no numeral can appear twice on the same list) and were administered to participants in counterbalanced order such that each list was completed an equal number of times for each visit across all participants (e.g., List 2 was presented to three participants at the pretraining visit, to three participants at the posttraining visit, and to three participants at the 1-month follow-up visit). For each participant, the 6-month follow-up visit list was identical to the pretraining visit list because only three alternative lists were available for the study. For the present study, Digits Forward and Digits Backward scores were used as measures of immediate verbal phonological memory capacity (e.g., phonological loop short-term memory, with fewer central executive demands) and immediate verbal working memory capacity, respectively.

Spatial span

The Spatial Span subtest of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fourth Edition Integrated (WISC–IV Integrated; Wechsler et al., 2004) requires participants to remember a series of spatial locations in forward (Spatial Span Forward) and backward (Spatial Span Backward) order, beginning with a series of two locations. Like the Digit Span subtest, the span length of items on each section of the Spatial Span subtest increases incrementally by an additional location if the participant can complete at least one of two items presented for each span length. For the screening visit, the standard WISC–IV Integrated items and directions were used; for the pretraining, posttraining, and 1-month follow-up visits, new location lists were used, consisting of randomly generated locations (no location appearing twice in the same series) that were presented in counterbalanced order to participants so that each list was administered an equal number of times for each visit across all participants. The 6-month follow-up visit Spatial Span lists were identical to the pretraining visit lists. In the present study, the Spatial Span Forward score was used as a measure of visual-spatial sequential memory capacity (e.g., visuospatial sketchpad, with less involvement of the central executive), whereas the Spatial Span Backward score was used as a measure of visual-spatial working memory capacity.

Working memory behavior ratings

Parents completed the BRIEF (Gioia et al., 2000), an 86-item rating scale of the child’s behavioral and cognitive executive functioning, at each study visit. Parents were instructed to complete the BRIEF based on child behavior during the previous week. The Working Memory subscale of the BRIEF (BRIEF:WM) consists of 10 items measuring the ability to focus, hold, and use information in memory during completion of tasks. BRIEF:WM scores can be converted to T-scores by age and gender, based on a large normative sample. In the present study, BRIEF:WM scores were used as measures of working memory skills in everyday environments.

Speech-Language Efficacy Measure

Sentence repetition

The Sentence Memory subtest of the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning—Second Edition (WRAML2; Sheslow & Adams, 2003) requires participants to repeat sentences of varying lengths, beginning with a two-syllable sentence and progressing to sentences with over 30 syllables. Individual items are scored on a 0-1-2 scale, with a score of 2 indicating no errors during sentence repetition; 1 indicates one error; and 0 indicates two or more errors. The total raw subtest score is the sum of individual item scores. The WRAML2 Sentence Memory raw score can be converted to a scaled score (normative mean = 10, SD = 3) based on a large, representative normative sample. This subtest evaluates a variety of basic speech-language skills that are commonly affected in children with CIs, including speech perception, memory, and production. It was administered as a measure of sentence-repetition skills at only three study visits (the pretraining, posttraining, and 6-month follow-up visits), in order to reduce practice effects with the items, because no alternative conormed sentence lists were available.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 17.0. Descriptive statistics are reported for the feasibility and acceptability measures at posttraining. For the efficacy measures (Working Memory and Speech-Language), raw scores were used in analyses of change across study periods, and norm-based scores (either scaled scores or T-scores) were used to compare the sample to scale norms. Both nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests and parametric paired t tests were used to evaluate change from baseline to endpoint during each study period. Because both of these types of tests provided similar results, only the t test results are reported here (a table of the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-ranks test results is available from the authors). The waiting period investigated change in scores between the screening and pretraining visits (no intervention). Change for the other three periods compared the endpoint score for that period to the pretraining visit score: (a) the training period evaluated change based on endpoint score immediately after training; (b) the 1-month follow-up period evaluated change from the pretraining visit to the 1-month follow-up; and (b) the 6-month follow-up period investigated change from the pretraining visit to the 6-month follow-up. For each efficacy measure, standardized change scores were derived by subtracting the endpoint score from the baseline score and dividing by the sample standard deviation of the baseline scores [(Time 2 – Time 1) / SDTime1]; thus, these scores show the number of standard deviations of change in a measure at the end of a time period, relative to the beginning of that period. Using conventions suggested by Cohen (1988) for standardized mean differences between groups, standardized change scores of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 were considered to reflect “small,” “medium,” and “large” effects, respectively.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participants scored in the average range on a measure of nonverbal intelligence and did not differ from the normative mean (WISC–IV Integrated Matrix Reasoning scaled score, M = 11.7, SD = 3.7, range = 8–18, t[8], in comparison to normative mean of 10 = 1.36, p < .22). Six of the nine study subjects scored below the Digit Span total score normative mean scaled score of 10 (five subjects scored 1 SD below the normative mean or lower), and six subjects also scored above the BRIEF:WM normative mean T-score of 50 (two subjects scored 1 SD above the normative mean or higher). However, average screening visit scaled scores for Digit Span Backward, M = 11.0, SD = 2.60, t(8) = 1.16, p < .29; Spatial Span Forward, M = 9.3, SD = 2.5, t(8) = 0.80, p < .45, and Spatial Span Backward, M = 11.0, SD = 2.6, t(8) = 1.16, p < .29; and BRIEF:WM, M = 54.7, SD = 8.6, t(8) = 1.63, p < .15, were not significantly different from scale norms. On the other hand, sample mean scaled scores for Digit Span Forward at the screening visit, M = 5.78, SD = 3.90, t(8) = 3.25, p < .02, and sentence repetition at the pretraining visit (the first administration of the WRAML2 Sentence Memory subtest), M = 7.2, SD = 2.1, t(8) = 3.95, p < .004, were significantly below average compared with scale norms. Most participants (n = 6) completed all 25 days of working memory training; other participants completed 20, 21, and 23 training days within a 28- to 47-day training window. Because a minimum of 20 training days was required to complete the training program, all participants were considered to have finished the working memory training. The mean duration of the training period was 35.8 days (SD = 4.9). All subjects returned for the posttraining, 1-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up visits and completed all measures at those visits.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Participants showed improvement on all Cogmed exercises during training. For every Cogmed exercise except one (Decoder), at least 89% of participants showed improvement, and the exercises showed a performance improvement value of 0.70 or higher. Results for the Decoder exercise (mean performance improvement value = 0.22; 44% of participants showed improvement) were probably affected by the fact that participants received only 5 training days on that exercise during the 5-week Cogmed training period (as is standard for Cogmed training).

On the PFQ, parents reported that children had no difficulty hearing or understanding the Cogmed exercises (see Table 1). Most (67%–78%) parents reported that the program took significant effort, especially during the final week. About half of families reported being satisfied with the program, would recommend it to others, and believed that it helped their child’s attention and memory. A small percentage (0%–11%) reported dissatisfaction with the program or did not believe that it helped the child’s attention or memory.

Efficacy: Working Memory

With the exception of the Spatial Span Forward test, the sample showed no mean improvement on any measures of working memory during the waiting period (screening to pretraining visits; see Table 2), indicating that practice/familiarity effects on the working memory measures were minimal. During the training period (pretraining to posttraining visits), sample scores improved significantly on Digits Forward, Spatial Span Forward, Spatial Span Backward, and BRIEF:WM scores, with standardized change values showing average improvement of about one-half SD or more over pretraining values (see Table 2). At posttraining, the sample mean scaled score for Digit Span Forward (the only working memory subtest to differ significantly from scale norms prior to working memory training) no longer differed statistically from scale norms, M = 7.78, SD = 3.70, t(8) = 1.80, p < .11.

Table 2.

Working memory and sentence-repetition change over study periods.

| Measure | Screening | Pretraining | Posttraining | 1-Month | 6-Month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digits Forward | |||||

| M (SD) | 6.00 (1.94) | 6.44 (1.88) | 7.56 (1.74) | 7.67 (1.87) | 6.78 (1.72) |

| Period change (t) | 0.23 (1.18) | 0.60 (2.44)* | 0.65 (3.77)** | 0.18 (1.00) | |

| Digits Backward | |||||

| M (SD) | 5.00 (1.87) | 4.78 (1.72) | 5.33 (1.41) | 5.33 (2.06) | 4.78 (1.39) |

| Period change (t) | −0.11 (0.43) | 0.32 (1.64) | 0.32 (1.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | |

| Spatial Span Forward | |||||

| M (SD) | 6.56 (1.42) | 8.11 (1.62) | 9.00 (1.80) | 8.67 (2.06) | 8.22 (2.28) |

| Period change (t) | 1.09 (3.09)* | 0.55 (2.87)* | 0.35 (1.10) | 0.07 (0.21) | |

| Spatial Span Backward | |||||

| M (SD) | 6.44 (1.33) | 6.22 (1.86) | 7.78 (2.33) | 7.56 (2.46) | 6.89 (2.15) |

| Period change (t) | −0.17 (0.43) | 0.84 (2.68)* | 0.72 (1.63) | 0.36 (1.63) | |

| BRIEF:WM | |||||

| M (SD) | 16.89 (3.92) | 17.11 (3.72) | 15.33 (3.61) | 16.22 (3.93) | 16.44 (3.50) |

| Period change (t) | 0.06 (0.36) | −0.48 (2.46)* | −0.24 (0.90) | −0.18 (0.80) | |

| Sentence Repetition | |||||

| M (SD) | – | 18.56 (2.74) | 20.44 (3.01) | – | 21.22 (4.60) |

| Period change (t) | 0.69 (6.11)*** | 0.97 (3.34)** |

Note. Period change scores are standardized change scores, derived by subtracting the endpoint score from the baseline score and dividing by the sample SD of the baseline scores, [(Time 2 – Time 1)/SDTime 1]. Paired t-test values (t; df = 8) are listed under the endpoint of the period for which the paired comparisons are made. BRIEF:WM = Working Memory subtest of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning. Dashes indicate measure not given as described in text. Blank cells indicate “not applicable.”

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The magnitude of gains at posttraining was maintained only for Digits Forward during the 1-month follow-up period as compared with pretraining. At 1-month follow-up, average standardized change scores from pretraining for Digits Backward, Spatial Span Forward, and BRIEF:WM were in the one-fourth to one-third SD range but did not reach statistical significance. For Spatial Span Backward at 1-month follow-up, the mean standardized change score was large (0.72 SD) but did not reach statistical significance (p < .15). At 6-month follow-up, the magnitude of standardized change for all working memory measures across the sample had dropped to 0.18 or lower, with the exception of Spatial Span Backward, standardized change = 0.36, t(8) = 1.63, p < .15 (see Table 2).

Efficacy: Speech-Language (Sentence Repetition)

The sentence-repetition task (WRAML2 Sentence Memory subtest) was administered only at the pretraining, posttraining, and 6-month follow-up visits in order to reduce practice effects because alternative co-normed sentence lists were not available. During the training period, sentence-repetition raw scores improved significantly (see Table 2), with an increase of 0.69 SD over the pretraining value. Improvement in sentence repetition continued during the 6-month follow-up period, with a final raw score that was significantly improved by almost 1 SD greater than the pretraining score. Analyses with WRAML2 Sentence Memory scaled scores mirrored those for the raw scores (as expected, because scaled scores are derived from raw scores): At posttraining, the sample mean scaled score for sentence repetition (M = 8.33, SD = 2.45) was statistically significantly improved, t(8) = 5.55, p < .001, from the sample mean scaled score at pretraining (M = 7.22, SD = 2.1). Similarly, at 6-month follow-up, the sample mean scaled score for sentence repetition (M = 8.89, SD = 3.6) was also significantly improved, t(8) = 2.67, p < .03, compared with pretraining. Importantly, at posttraining and follow-up, WRAML2 Sentence Memory scaled scores fell within the broad average range (with means corresponding approximately to the 28th and 35th percentiles, respectively) and were no longer statistically significantly different from the scaled score (normative) mean of 10, t(8) = 2.04, p < .08, and t(8) = 0.92, p < .39, respectively.

Efficacy: Individual Change Scores

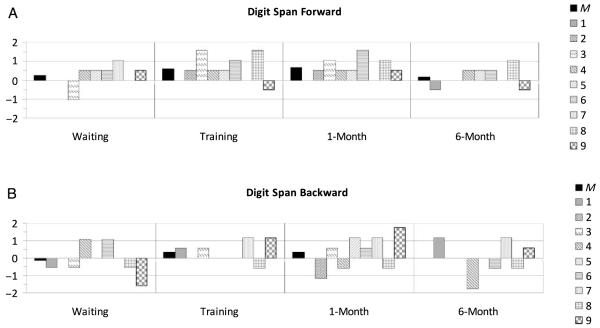

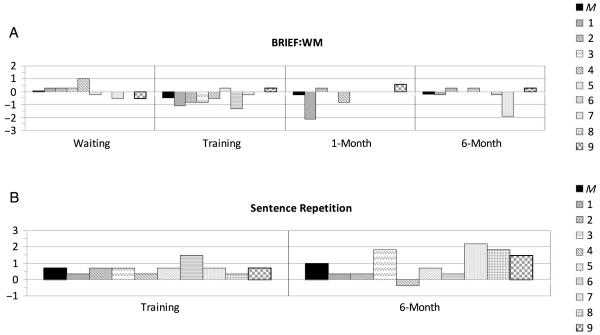

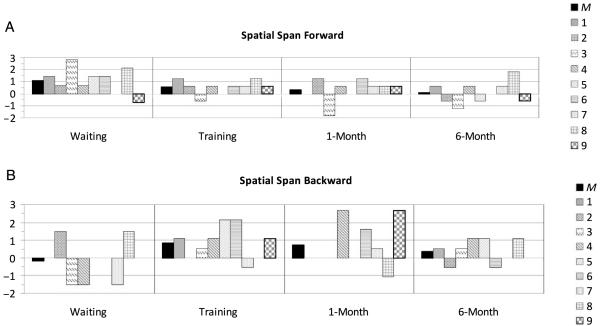

Standardized change in efficacy measures for each study participant is shown in Figures 1-3. Typically, about half or less of the sample showed improvement in the medium range or greater (standardized change > 0.50) during the waiting period. Only for Spatial Span Forward (78%) and Digits Forward (56%) did more than half of participants show medium improvement or greater during the waiting period.

Figure 1.

Individual participant change in digit span during study periods. Panel A: Digit Span Forward standardized change scores from baseline for mean sample score (M) and by individual subject (denoted with numerals). Because baseline is Screening Visit (Visit 1) for Waiting Period and Pretraining Visit (Visit 2) for all other periods, bars for Training Period, 1-Month Follow-Up, and 6-Month Follow-Up reflect improvement over and above improvement during the Waiting Period. Panel B: Digit Span Backward standardized change scores from baseline for mean sample score (M) and by individual subject (denoted with numerals). Because baseline is Screening Visit (Visit 1) for Waiting Period and Pretraining Visit (Visit 2) for all other periods, bars for Training Period, 1-Month Follow-Up, and 6-Month Follow-Up reflect improvement over and above improvement during the Waiting Period.

Figure 3.

Individual participant change in parent-reported working memory behavior and sentence repetition during study periods. Panel A: BRIEF-WM standardized change scores from baseline for mean sample score (M) and by individual subject (denoted with numerals). Because baseline is Screening Visit (Visit 1) for Waiting Period and Pretraining Visit (Visit 2) for all other periods, bars for Training Period, 1-Month Follow-Up, and 6-Month Follow-Up reflect improvement over and above improvement during the Waiting Period. Negative standardized change scores indicate improvement in working memory behavior on the BRIEF:WM. Panel B: Sentence repetition (Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning—Second Edition [WRAML 2] Sentence Memory) standardized change scores from baseline for mean sample score (M) and by individual subject (denoted with numerals). Baseline is Pretraining Visit (Visit 2) for Training Period and 6-Month Follow-Up.

On the other hand, during the training period, between 44% (Digits Backward) and 78% (Spatial Span Forward) of participants demonstrated medium improvement or greater on the efficacy measures, above and beyond improvement shown in the waiting period (see Figures 1-3). For most of the efficacy measures (Digits Forward, Spatial Span Backward, Sentence Memory), about 67% of participants showed medium improvement or better during the training period. All nine participants showed some improvement in sentence-repetition performance during the training period (see Figure 3).

With the exception of the BRIEF:WM score, the number of participants showing medium improvement or greater was relatively stable from the training period to the 1-month follow-up (see Figures 1-3). Numbers of participants in the medium range of improvement or greater increased slightly from the training period to the 1-month follow-up period for Digits Forward (67%–78%) and Digits Backward (44%–56%), whereas the number of participants in the medium range of improvement decreased slightly from the training period to the 1-month follow-up period for Spatial Span Forward (78%–67%) and Backward (67%–44%).

A more significant drop in number of participants reaching the medium range or greater in improvement was seen in the 6-month follow-up period for all measures except Sentence Memory. Between 33% (Digits Backward) and 56% (Spatial Span Backward and Sentence Memory) of participants showed medium improvement or greater between pretraining and 6-month follow-up scores, with Digits Forward and Spatial Span Forward falling between these extremes. BRIEF:WM scores showed the greatest drop at 6-month follow-up, with only one participant showing medium improvement or greater and three participants showing small improvement or greater. Interestingly, almost all (89%) of the sample continued to show at least small improvement in Sentence Memory scores at 6-month follow-up, and nearly half (44%) of the sample showed large improvement in Sentence Memory scores at 6-month follow-up (see Figures 1-3).

Discussion

The results of this pilot study demonstrated statistically significant short-term improvement in verbal working memory capacity, nonverbal working memory capacity, and real-world working memory behaviors in a sample of nine children with CIs, following completion of a 5-week working memory training program. Approximately two-thirds of participants showed a medium (standardized change score > 0.50) magnitude of improvement on most efficacy measures immediately following training, and this improvement was maintained at 1-month follow-up. The mean sample magnitude of improvement and number of participants showing medium-range improvement or greater dropped for most measures by the 6-month follow-up, but at least one third of participants continued to show medium-range improvement for most efficacy measures at 6-month follow-up. The largest improvements were found for sentence repetition, which increased significantly in the sample at posttraining and 6-month follow-up. Furthermore, over half of the sample showed a medium magnitude of improvement in sentence repetition at the posttraining and 6-month follow-up visits.

To our knowledge, this study is the first systematic investigation of a computer-based working memory training program for children who are deaf and who have CIs. Because the Cogmed program was originally developed for normal-hearing children, a key first step was to evaluate the feasibility, appropriateness, and acceptability of this working memory training program for a sample of children who are deaf and who have CIs. Results of feasibility and acceptability analyses showed no problems with hearing or understanding the training exercises, and sample mean performance scores improved for all exercises. Thus, this sample of children who are deaf and who have CIs had no problem with the basic exercises of the Cogmed program. Additionally, over half of parents stated that they were happy with the results of Cogmed, and nearly half agreed with statements indicating that they saw improvement in the child’s attention and working memory. Two-thirds said that they would recommend the program to others. However, about three-quarters of parents indicated that the program took a significant amount of effort from parent and child, particularly during the final week of the program. These feasibility, appropriateness, and acceptability results indicate that Cogmed can be appropriate and acceptable for children with CIs but that a high degree of motivation and effort are needed for its implementation.

Although the study sample had average nonverbal intelligence, the participants’ initial (screening visit) scores on measures of digit span forward and sentence repetition were significantly below average relative to same-aged peers. On the other hand, the sample did not differ from scale norms on measures of digit span backward or on the BRIEF:WM, despite the fact that average or lower scores on digit span or the BRIEF:WM were required for study entry. Two factors appear to have contributed to this finding. First, weaknesses in the Digit Span Forward score appear to have been the major factor qualifying most subjects for study entry. Over half of subjects scored lower than 1 SD below the mean on this measure, and even with a sample mean Digits Backward score greater than the normative mean, there was a trend for the total Digit Span score (the sum of Digits Forward and Digits Backward) to be lower than the normative mean, t(8) = 1.93, p < .09. Second, because over half of the sample had BRIEF:WM T-scores of 55 or greater (0.5 SD greater than the normative mean), it is possible that the study may not have had sufficient power to detect the smaller elevation of BRIEF:WM scores. Nevertheless, sample descriptive statistics on working memory and sentence-repetition measures indicate that the most severe deficits were found for immediate short-term verbal memory and language measures.

Substantial weaknesses in immediate verbal memory and sentence-repetition skills are commonly found in samples of children with CIs (e.g., Pisoni et al., in press), supporting the premise that intervention for memory and sequential processing skills may be appropriate and effective for children with CIs who are experiencing language delays following cochlear implantation. Delays in immediate verbal memory capacity affect the amount of information that a child has available for processing and long-term learning (e.g., accumulation of information, verbal fluency, etc.). Because early experiences and activities with acoustic signals and sound patterns in the environment are critical for normal development of sequential processing skills (Conway et al., 2009) and construction of internal phonological representations and processes (Pisoni et al., in press), atypical auditory experience (including underspecified cognitive representations of degraded acoustic–phonetic input signals) may have broad effects on the development of basic neurocognitive functions including attention, verbal working memory, sequential spatial and verbal processing, and executive functioning (Pisoni et al., 2008). As a result, interventions specifically designed to address the basic underlying verbal working memory deficits of children who are deaf and who have CIs may be expected to have wide-ranging effects that generalize well beyond the trained working memory tasks and stimuli themselves and show transfer to nontrained language perception and memory tasks.

Generalization and transfer-of-training effects were demonstrated in this study of working memory training in children who are profoundly deaf and who have CIs. The Cogmed exercises are administered on a computer, are predominantly visual, and differ markedly from the working memory measures used to evaluate efficacy in this study. In fact, seven of the 12 Cogmed training exercises exclusively involve visual-spatial memory, and another three exercises involve memory for spatial locations that are paired with auditory–verbal stimuli (numbers or letters). Only two of the 12 Cogmed exercises predominantly involve verbal memory. Despite the marked differences between these Cogmed trained tasks and the working memory efficacy measures in this study, participants showed statistically significant improvement on performance measures of verbal working memory (Digit Span) as well as visual-spatial working memory (Spatial Span) after training on the Cogmed tasks. Additionally, parents reported improvement in participants’ day-to-day working memory and attention skills on a questionnaire measure (BRIEF:WM). Taken together, these findings indicate that improvement demonstrated by participants on the actual trained tasks of the Cogmed program extended beyond those tasks to other, more applied working memory tasks. Importantly, transfer of these working memory improvements to language skills was also shown by significant improvement in sentence repetition, suggesting that the effects of Cogmed in one neurocognitive area (working memory capacity) may transfer to another core area of language processing (sentence repetition) for many children with CIs (Geers et al., 2003).

Despite the improvement in most working memory scores immediately following training, only Digits Forward continued to show statistically significant improvement at 1-month follow-up. Inspection of the actual magnitude of improvement in working memory test scores at 1-month follow-up (by sample mean standardized change scores in Table 2 and by participant in Figures 1-3) revealed that the backward span (Digits and Spatial) variables had almost the same amount of improvement at 1-month follow-up as at posttraining. Spatial Span Forward declined somewhat but still had a standardized change score of 0.35, with a majority of participants showing a medium magnitude of improvement or greater. Therefore, for the span-based working memory measures at 1-month follow-up, it appears likely that the small study N may have limited the statistical power to detect significance of small to medium effect sizes. For the BRIEF:WM, on the other hand, the magnitude of decline at 1-month follow-up was greater than that of the span-based working memory measures; the standardized change at 1-month follow-up was smaller; and the number of participants showing medium improvement or greater at 1-month follow-up was small (2/9). Therefore, parent-reported day-to-day working memory and attention may show a faster decline than performance-based working memory abilities over a 1-month follow-up period.

More significant declines in all working memory scores across the study sample were observed by 6-month follow-up, with no working memory variable showing statistically significant improvement from the pretraining visit. However, inspection of individual participant scores revealed that some participants may have retained residual improvements through the 6-month follow-up (e.g., subjects 4 and 8 for Digits Forward, Spatial Span Forward, and Spatial Span Backward), although the sample as a whole did not demonstrate statistically significant improvement. These declines for most participants in the sample may indicate that longer training or booster sessions may be required in order to maintain the working memory gains from the training period for an extended period of time.

For the language measure of sentence repetition, the mean pretraining scaled score of the sample was significantly lower than the normative scaled score mean and fell nearly 1 SD below the normative mean (18th percentile), demonstrating very significant delays on this measure. Improvements in the sample mean Sentence Memory score at posttraining and 6-month follow-up were highly significant and nearly universal in all of the children studied in the sample. In fact, more participants showed large improvements in sentence repetition at 6-month follow-up than at posttraining, and the average standardized change was greater at 6-month follow-up than at posttraining. Mean scaled scores for sentence repetition at posttraining and follow-up were within two-thirds SD of the mean (28th and 35th percentiles, respectively) and were not statistically different from the normative scaled score mean. These findings suggest that the improvement found in sentence repetition (reflecting core underlying skills of language/sentence perception, memory, and speech production) was clinically meaningful (reaching into the average range relative to norms) and may be more durable, lasting a longer period of time than improvement in working memory as measured by conventional span measures. Based on the current data, it is not possible to parse out the extent to which improvement in sentence repetition was a result of improvement in the specific components of the task (language/sentence perception, memory, speech production, sequencing, etc.), but given concurrent improvements on working memory measures such as Digit/Spatial Span, it is likely that some component of memory skills improvement contributed to improvement in sentence repetition.

The results of this study must be interpreted in the context of several important methodological limitations. As an initial pilot study of a novel intervention for children with CIs, this study had no placebo control, and participants were not blinded to condition. As a result, changes in scores may be influenced by practice or participant expectancy effects. The waiting period was built into the study design in order to address several possible concerns about practice effects, allowing us to evaluate the effects of retesting during a period in which no intervention took place. With the exception of Spatial Span Forward, no working memory measure increased significantly during the waiting period, and (other than Spatial Span Forward) only Digit Span Forward showed a magnitude of improvement in the small range or higher (i.e., standardized change > 0.20; see Table 2) during the waiting period. This pattern of results provides support for the hypothesis that the improvements observed after the training period reflected a real meaningful effect of working memory training, even though a placebo condition was not part of the study design. Furthermore, administration of the working memory measures twice (at screening and pretraining visits) before Cogmed training was initiated allowed for much of the benefits of practice and familiarity to be accounted for prior to initiating training. Because these practice benefits would be reflected predominantly in the pretraining visit scores on the working memory variables, the use of the pretraining visit as the baseline score for posttraining and follow-up measures factors out much of the benefit of practice in evaluating the significance of change during the training and follow-up periods. Finally, different test items were used for memory (span) tasks administered at the screening, pretraining, posttraining, and 1-month follow-up visits, preventing participants from learning or remembering any of the specific test items or sequences from previous administrations.

The sentence-repetition task, on the other hand, was administered only three times during the study (pretraining, posttraining, and 6-month follow-up) because (unlike the span tests) its content could not be changed from one visit to the next. As a result, this task had fewer safeguards than the span tasks for evaluating or preventing practice effects. Sheslow and Adams (2003) investigated test–retest change in WRAML2 Sentence Memory subtest scores in a normal-hearing sample over a median period of 7 weeks between test administrations and reported a gain of 0.5 scaled score points (corresponding to a standardized change of 0.16). Similarly, a mean gain of 0.5 scaled score points (0.22 standardized change) over a median 3-week period was found for read-ministration of the Sentence Repetition subtest of the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment—Second Edition (NEPSY–II; a similar sentence-repetition task) in a normal-hearing sample (Korkman, Kirk, & Kemp, 2007). These standardized change values are much lower than standardized change values found in this study after working memory training (0.69 at posttesting and 0.97 at 6-month follow-up), but evidence of a modest practice effect on sentence repetition tests in normal-hearing samples indicates the need for additional controlled studies in this area in order to more adequately account for potential practice effects. Additionally, one might expect some decline in practice effects over the 6-month period between the posttreatment and 6-month follow-up visit (especially relative to the shorter 5-week period immediately before and after working memory training), but improvement in sentence-repetition scores was maintained (and actually improved slightly) during that period of time. Hence, although there are some suggestions that the improvement in sentence-repetition performance following working memory training exceeds what would be expected from practice alone, there is a need for additional research of this topic, using blinded, placebo-controlled methods.

Participant expectancy effects (the expectation on the part of participants that they will improve as a result of the intervention, regardless of the actual intervention; a subtype of the Hawthorne effect) may have affected results because all participants received the working memory training and were aware of when the training took place. This may have the greatest potential effects on parental report (e.g., on the BRIEF:WM) if parents were primed to expect improvement. However, it is very unlikely that participants would improve on the working memory performance tests (Digit and Spatial Span) because of expectancy alone. Participants were motivated to do their best on these span-based tests at all visits, and the tests were administered individually by highly experienced examiners. Furthermore, recent findings have shown that in a large sample of children who are deaf and who have CIs (N = 112) over an 8- to 10-year period, Digit Span Forward improves by only about one digit, and Digit Span Backward shows little, if any, improvement (Pisoni et al., in press). Therefore, improvements of the magnitude demonstrated during the 5-week training period typically take up to 8 years or more to occur naturally in samples not receiving targeted working memory intervention.

The small sample size in this pilot study may have affected the power of some statistical analyses. Because it is possible that some of the nonsignificant results (especially those in the small to medium range) would have reached statistical significance in a larger sample, nonsignificant study results should be interpreted cautiously. Furthermore, there is a need for additional speech and language measures to better understand the effects of working memory training on language outcomes. It should also be noted that it was not possible to obtain waiting period and 1-month follow-up evaluations of change in sentence repetition because of concerns about practice effects (the same sentences were used at all administrations). Therefore, we cannot say how much of the intervention effect reported here was due to prior exposure to the sentence-repetition task. On the other hand, it seems very unlikely that a simple practice effect for the sentences would last through a 6-month follow-up period. Moreover, the 6-month follow-up results for sentence repetition were even greater than those at posttraining, suggesting continued improvement well after the working memory training was completed.

This study demonstrated improvements in working memory capacity and sentence-repetition skills in a small pilot sample of children who are deaf and who have CIs. Based on the present findings, future research studies should investigate the effects of working memory training using randomized, placebo-controlled methods, with larger samples of children with CIs. More extensive process and outcome measures of language and other neurocognitive functioning may help to provide additional converging information about the generalizability and transfer of the training effects, as well as the underlying neurocognitive processes responsible for this change. It will be especially important to track change over longer follow-up periods and to test the impact of factors (e.g., longer training duration, booster sessions) that may extend the effect of training over a longer period of time. Ultimately, this knowledge will provide valuable new information about novel, process-based interventions that address the core underlying neurocognitive factors affected by deafness and CI use that influence speech, language, and other neurocognitive and behavioral outcomes in this population.

Figure 2.

Individual participant change in spatial span during study periods. Panel A: Spatial Span Forward standardized change scores from baseline for mean sample score (M) and by individual subject (denoted with numerals). Because baseline is Screening Visit (Visit 1) for Waiting Period and Pretraining Visit (Visit 2) for all other periods, bars for Training Period, 1-Month Follow-Up, and 6-Month Follow-Up reflect improvement over and above improvement during the Waiting Period. Panel B: Spatial Span Backward standardized change scores from baseline for mean sample score (M) and by individual subject (denoted with numerals). Because baseline is Screening Visit (Visit 1) for Waiting Period and Pretraining Visit (Visit 2) for all other periods, bars for Training Period, 1-Month Follow-Up, and 6-Month Follow-Up reflect improvement over and above improvement during the Waiting Period.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Research Support Funds Grant to William G. Kronenberger and by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants R01 DC-00111-31 and R01 DC-009581-01 to David B. Pisoni. Portions of this study were presented at the 12th Symposium on Cochlear Implants in Children in Seattle, WA (June 2009) and at the Cogmed Conference in Austin, TX (November 2009).

References

- Archibald LMD, Joanisse MF. On the sensitivity and specificity of nonword repetition and sentence recall to language and memory impairments in children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:899–914. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0099). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience. 2003;4:829–839. doi: 10.1038/nrn1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Working memory, thought, and action. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. ADHD and the nature of self-control. Guilford; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bavelier D, Dye MWG, Hauser PC. Do deaf individuals see better? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;10:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer J, Pisoni DB, Kronenberger W. Executive function in children with cochlear implants: The role of organizational-integrative processes. Volta Voices. 2009:18–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair FX. A study of the visual memory of deaf and hearing children. American Annals of the Deaf. 1957;102:254–263. [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder RA, Pisoni DB. Speech timing and working memory in profoundly deaf children after cochlear implantation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2003;85:63–88. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0965(03)00033-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Pisoni DB, Geers AE. Some measures of verbal and spatial working memory in eight- and nine-year-old hearing-impaired children with cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing. 2001;22:395–411. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Pisoni DB, Kirk KI. Working memory spans as predictors of spoken word recognition and receptive vocabulary in children with cochlear implants. The Volta Review. 2002;102:259–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. Children’s Memory Scale. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Conti-Ramsden G, Botting N, Faragher B. Psycholinguistic markers for specific language impairment (SLI) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42:741–748. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway CM, Pisoni DB, Kronenberger WG. The importance of sound for cognitive sequencing abilities: The auditory scaffolding hypothesis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:275–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. Working memory capacity. Psychology Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW, Tuholski SW, Laughlin JE, Conway ARA. Working memory, short-term memory, and general fluid intelligence: A latent-variable approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128:309–331. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueras B, Edwards L, Langdon D. Executive function and language in deaf children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2008;13:362–377. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enm067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers A, Brenner C, Davidson L. Factors associated with development of speech perception skills in children implanted by age five. Ear and Hearing. 2003;24(Suppl.):24S–35S. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051687.99218.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J, Gathercole SE, Dunning DL. Adaptive training leads to sustained enhancement of poor working memory in children. Developmental Science. Advance online publication. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J, Gathercole SE, Place M, Dunning DL, Hilton KA, Elliott JG. Working memory deficits can be overcome: Impacts of training and medication on working memory in children with ADHD. Applied Cognitive Psychology. Advance online publication. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg T, Fernell E, Olesen PJ, Johnson M, Gustafsson P, Dahlstrom K, Westerberg H. Computerized training of working memory in children with ADHD—A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:177–186. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkman M, Kirk U, Kemp S. NEPSY–II. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Luria AR. The working brain: An introduction to neuropsychology. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering SJ, Gathercole SE. Working Memory Test Battery for Children. Harcourt Assessment; London, United Kingdom: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Cleary M. Measures of working memory span and verbal rehearsal speed in deaf children after cochlear implantation. Ear and Hearing. 2003;24(Suppl.):106S–120S. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051692.05140.8E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Cleary M. Learning, memory, and cognitive processes in deaf children following cochlear implantation. In: Zeng FG, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Springer handbook of auditory research: Auditory prosthesis. X. Springer; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 377–426. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Conway CM, Kronenberger W, Henning S, Anaya E. Executive function, cognitive control, and sequence learning in deaf children with cochlear implants. In: Marschark M, Spencer PE, editors. The Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2010. pp. 439–457. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Conway CM, Kronenberger W, Horn DL, Karpicke J, Henning S. Efficacy and effectiveness of cochlear implants in deaf children. In: Marschark M, Hauser P, editors. Deaf cognition: Foundations and outcomes. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 52–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni D, Geers A. Working memory in deaf children with cochlear implants: Correlations between digit span and measures of spoken language. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2000;185:92–93. doi: 10.1177/0003489400109s1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Kronenberger WG, Roman AS, Geers AE. Measures of digit span and verbal rehearsal speed in deaf children after more than 10 years of cochlear implant use. Ear and Hearing. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181ffd58e. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheslow D, Adams W. Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning—Second Edition. Wide Range; Wilmington, DE: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- St. Clair-Thompson HL. Backwards digit recall: A measure of short-term memory or working memory? European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2010;22:286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes SF, Wong AM, Fletcher P, Leonard LB. Nonword repetition and sentence repetition as clinical markers of specific language impairment: The case of Cantonese. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:219–236. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman MT, Pierpont EI. Specific language impairment is not specific to language: The procedural deficit hypothesis. Cortex. 2005;41:399–433. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Thought and language. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D, Kaplan E, Fein D, Kramer J, Morris R, Delis D, Maerlender A. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fourth Edition Integrated. Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 2004. [Google Scholar]