Summary

Background. Acid assault is one of the most brutal of crimes. This crime is not meant to kill but to punish the victim or to destroy the victim’s social life. This violent act usually occurs in third-world countries. The aim of this paper is to assess the epidemiological factors that steer a person toward such a violent act. Method. From May 2004 to October 2010, the charts of victims of acid violence referred to the Motahari Burn Center in Iran were reviewed. During this 6-yr period, 59 patients were included in this retrospective study. We identified the aetiology and the extent of the damage that was produced as a result of throwing corrosive chemicals onto the victim’s body for the purpose of revenge. Results. The cases reviewed concerned 51% male patients and 49% female. The face and upper body were the most commonly injured areas, and the most common assailant was a close family member. Conclusion. The authors believe that lack of information about the catastrophic outcome of this action, plus the widespread availability of strong, destructive chemicals, are the main reasons for the rising incidence of this crime.

Keywords: acid violence, severe burn, epidemiology

Abstract

Contexte général. L’emploi de l’acide dans les attaques sur les personnes constitue un des crimes les plus brutaux parce que l’intention criminelle n’est pas de tuer la victime mais de la punir ou de détruire sa vie sociale. Cet acte violent se produit habituellement dans le tiers-monde. Les auteurs de cette étude se sont proposé d’évaluer les facteurs épidémiologiques qui portent un individu à commettre un tel acte de violence. Méthode. Les données de toutes les victimes de la violence due à l’emploi de l’acide pendant la période de mai 2004 jusqu’à octobre 2010 traitées au Centre des Grands Brûlés de Mohatariah (Iran) ont été revues, et 59 patients ont été inclus dans cette étude rétrospective. Les auteurs ont établi l’étiologie et la gravité des lésions causées par le lancement de produits chimiques corrosifs sur le corps de la victime dans le but de se venger. Résultats. La distribution sexuelle des patients considérés était de 51% hommes et 49% femmes. Le visage et la partie supérieure du corps se sont démontrées les zones les exposées aux agressions de ce type, et l’agresseur était communément un des parents les plus proches. Conclusion. Les auteurs expriment l’opinion que la fréquence toujours croissante de ce crime est due principalement à l’absence d’information sur les résultats de ce type d’action et à la faciliter de trouver au marché des substances chimiques très fortes qui possèdent une capacité destructrice énorme.

Introduction

The intentional throwing of acid on someone’s face and body is used as punishment or revenge and can be done with a minimal amount of acid. This ominous act has a lifelong harmful effect on the victim’s appearance (Figs. 1, 2). The sinister aim of such chemical assault is to deliberately ruin a person’s face as a punishment.

Fig. 1, 2. Before and after photographs of acid violence showing irreversible disfigurement of the victim’s face.

The motives for this act are usually marriage problems, such as refusal of a marriage proposal,1 extramarital affairs, or divorce in order to be with another person. Poverty, low socioeconomic class, and larceny are other common reasons for which acid assaults are committed.

This study was undertaken because of the high prevalence of catastrophic chemical assaults in Iran. Its aim is to perform statistical analyses and to identify the aetiology of this crime and ways of preventing such grievous acts. Acids and bases are available in every grocery store for various purposes, such as the unclogging of pipes,2 and are also available from car batteries.

We investigated these injuries with the intention of proposing strategies for their prevention.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted at the Motahari Burn and Reconstructive Hospital, which is the referral centre for a 10-million-resident cosmopolitan city and its neighbouring provinces. The study was designed to determine the epidemiological factors associated with acid burns resulting from assault in Iran.

The study was performed between May 2004 and October 2010. Retrospective chart reviews of admitted patients were performed to assess the frequency of acid burns related to chemical assault. Over the 6-yr period, 59 patients were included in the study (30 male, 51%; 29 female, 49%).

The patients’ mean age was 36 yr (range, 4 to 74 yr). Five patients (8.4%) died owing to severe injuries. The average extent of injury was 30% of the total body surface area (TBSA).

Most patients were married (71%) (Table I). Fifty per cent of female patients were attacked by their husbands or relatives, the rest by strangers. Male patients were attacked either by their wives (12%), by strangers (36%), or during a quarrel (17%); in the remaining 35% of cases, the attackers were not recorded in the patients’ charts.

Table I. Victims’ marital status.

All patients considered, the assaults were carried out by a spouse in 32.2% of cases, by another family member (12%) or a stranger (39%), or else the assaults were the result of a quarrel or theft (15.2%) or, in one case, of suicide (1.6%) (Table II). The mean hospitalization period was 39 days, and 40% of the patients had 10% to 20% burns.

Table II. Characteristics of the perpetrators.

Facial involvement was common and was observed in 72.8% of cases. The upper limbs, the trunk, and the lower limbs were involved in respectively 86.4%, 67.7%, and 32.2% of the cases.

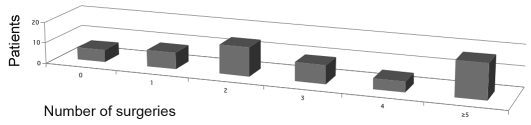

The total percentage of patients who underwent surgery for debridement or reconstruction was 89.8%,3 and 76% had at least two surgical procedures.

The results showed there was no statistically significant difference between the numbers of male and of female victims (51% male, 49% female). However, 40% of male victims were single, in comparison with 12% of females.

Table III. Frequency of surgery.

Discussion

Compared to the industrial world, Iran and neighbouring third-world countries have a high incidence of acid burn violence. The actual incidence in Iran is likely to be much higher than that registered at the Motahari Burn Center. This is due to a variety of reasons - a minor trauma that may not be referred to a major burn centre or referral may be to other specialties, such as ophthalmology in cases of eye injury. As acid assaults generally occur in the depressed socioeconomic areas of smaller cities, victims may receive medical care at their local clinics. Male victims, for various psychosocial reasons, often do not report the true cause of their burn. The purpose of writing this paper was to investigate the reasons for the high incidence of acid attacks, which cause irreversible damage to the appearance of young, active individuals, and to try to identify ways of preventing future attacks.

The high and increasing incidence of acid attacks, which are frequently reported in the daily newspapers in Iran, is a call for medical and social authorities to search for solutions to prevent such violence acts and to identify strategies for keeping strong caustic agents out of the reach of ordinary people. Two easy ways would be to stop manufacturing wet car batteries and to make plumbing agents available only to professionals.

Mannan et al.3 reported the largest study of acid violence (771 cases). After reviewing the worldwide literature, they found that, over the last 40 years, Jamaica,Bangladesh, and Taiwan were among the areas with the highest incidence of acid assault in the world. Male victims were more common in Jamaica, while in Bangladesh and Taiwan females were the predominant victims. The youngest victims were found in Bangladesh.

An article from China4 reported 337 cases, of which 40 (10.5%) were due to criminal assault, the rest being related to industrial accidents. In Azarbayejan, a province in northern Iran, 121 cases of chemical injury with multiple aetiology were reported in 2008.5 In this study, 111 cases (91.7%) were accidental, and 10 cases (8.3%) were classed as criminal assault. The frequency of this act is increasing in developing countries,6 such as Iran, and in some industrial cities, e.g. Hong Kong.7

The usual scenario of acid violence in most third-world countries and, surprisingly, in some developed ones8,9 is one in which the victim’s spouse uses concentrated sulphuric acid to gain revenge for an unsuccessful marriage or relationship provoked by social or economic reasons. The victims will suffer severe facial disfiguration and isolate themselves from social activities for the rest of their lives.9 Chemicals such as sulphuric acid from batteries or sodium hydroxide obtained from cleaning supplies are an affordable means of assault among lower socioeconomic groups.10

Acid attacks are terrible acts of vengeance, causing serious injuries to the victim’s face and body. The number of these attacks has increased in many urban and rural areas in the past few years. Survivors are driven to social isolation and the damage to their self-esteem forces them to leave work or school, which leads to illiteracy and poverty, thus further increasing the victims’ problems. The inefficacy of legal enforcement is demonstrated by the increased incidence of acid attacks.1 Multiple action will be required to reduce acid violence in third-world countries in the field of social awareness, economic and psychological support, rehabilitation, and strict law enforcement.1

Conclusion

The authors of this paper believe that limiting the use of caustic agents by the general population by reducing their availability might help to reduce the incidence of the catastrophic crime of acid burn violence. Investigation of the cultural and social reasons behind this crime should be the main strategy for its elimination or reduction. Discussing this crime and its terrible outcomes publicly may have controversial prevention effects and may even give ideas to people who are seeking a way to exact revenge.11

The authors recommend the wider use in the media of detailed information about the irreversible, terrible outcome of this crime and the legal penalties involved.

References

- 1.Begum A.A. Acid violence: A burning issue of Bangladesh - its medicolegal aspects. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2004;25:321–323. doi: 10.1097/01.paf.0000127389.00255.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bond S.J., Schnier G.C., Sundine M.J., et al. Cutaneous burns caused by sulfuric acid drain cleaner. J Trauma. 1998;44:523–526. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199803000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannan A., Ghani S., Clarke A., et al. Cases of chemical assault worldwide: A literature review. Burns. 2007;33:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie Y., Tan Y., Tang S. Epidemiology of 377 patients with chemical burns in Guangdong province. Burns. 2004;30:569–572. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maghsoudi I.M., Gabraely N. Epidemiology and outcome of 121 cases of chemical burn in East Azarbaijan province, Iran. Injury. 2008;39:1042–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olaitan P.B., Jiburum B.C. Chemical injuries from assaults: An increasing trend in a developing country. Indian J Plast Surg. 2008;41:20–23. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.41106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young R.C., Ho W.S., Ying S.Y. et al. Chemical assaults in Hong Kong: A 10-year review. Burns. 2002:651–653. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond S.J., Schnier G.C., Sundine M.J., et al. Cutaneous burns caused by sulfuric acid drain cleaner. J Trauma. 1998;44:523–526. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199803000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeong E.K., Chen M.T., Mann R. et al. Facial mutilation after an assault with chemicals: 15 cases and literature review. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1997;18:234–237. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branday J., Arscott G.D., Smoot E.C., et al. Chemical burns as assault injuries in Jamaica. Burns. 1996;22:154–155. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asaria J., Kobusingye O.C., Khingi B.A., et al. Acid burns from personal assault in Uganda. Burns. 2004;30:78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]