Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge and understanding of disease can influence time to presentation and potentially, therefore, cancer survival rates. The media is one of the most important sources of public health information and it influences the awareness and perception of cancer. It is not known if the reportage of cancer by the media is representative to the true incidence of disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The top 10 UK daily newspapers were assessed over a 1-year period for the 10 most common UK cancers via their on-line search facilities.

RESULTS

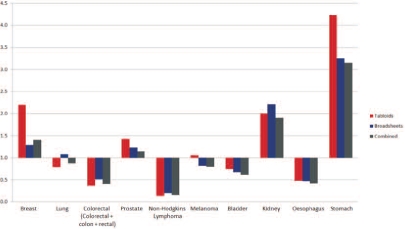

Of the 5832 articles identified, there was marked over-representation of breast, kidney and stomach cancer with ratios of prevalence to reporting of 1.4, 1.9 and 3.2 to 1, respectively. Colorectal, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, bladder and oesophageal cancers are all markedly under-represented with ratios of 0.4, 0.2, 0.6 and 0.4 to 1, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

A policy of media advocacy by health professionals could enhance the information provided by the media and thus reflect the true extent of disease. A partnership between health professionals and journalists could result in articles that are relevant to the population, informative and in a style and format that is easily comprehendible. Targeted public health information could highlight the ‘red-flag’ symptoms and break down any stigma associated with cancer. This enhanced awareness could improve the health-seeking behaviour of the general population and reduce the delay from symptoms to diagnosis.

Keywords: Media, Cancer, Newspaper coverage, Representation

The UK has one of the poorest cancer survival rates in Europe and an estimated 1 in 3 people develop cancer within their life-time. The two-week target, from referral from a general practitioner (GP) to a specialist, has tried to hasten the time patients take to receive both diagnosis and treatment of cancer.2 The increased speed of referral intends to improve outcomes by treating cancer at an earlier stage.1,2 However, patients often develop symptoms for some time prior to initial presentation.1,3–5 One of the postulated reasons for this delay is that public knowledge of cancer, and its signs and symptoms, is limited.1,4 Advertising strategies have been shown to increase public awareness of cancer, its risk factors and improve the public’s understanding of the disease.1,3,6–8

Of all of the information sources available to the general population, the media has been postulated at being the most important.8,9 Not only does the media decide which issues to present to the population, but it attaches a level of importance to them. Thus, the media may have an indirect role in how cancer (and other illnesses) is perceived, in terms of its prevalence, severity and outcomes. The media may also disseminate health information passively – where their audience is exposed to articles on subjects that they did not expect. This opportunistic provision of health information is in addition to advertisements from both government-funded institutions and charitable organisations. While newspapers do not exist as a health promotion platform, they may raise the overall awareness of the disease to the population.6,7,9,10 Newspaper coverage of medical issues may not be in-depth, but should be easily comprehendible and written at an appropriate reading age for their readers, which can contrast with patient information leaflets.9,11,12

In terms of what is reported by the print media, articles tend to be on subjects that are prevalent, relevant and of interest to the public. Articles depicting medical subjects are often influenced by non-medical issues, such as celebrity status or significant public events.7,10,13 Thus reportage of cancers may not be representative of actual disease and there may be a discrepancy in the prevalence of certain cancers with regard to true incidence.6,8 In terms of cancer coverage, no previous studies have assessed if the number of articles that exist in the print media reflect the incidence of the malignancy. The aim of this paper is to assess the media profile of the most common 10 cancers in the UK.

Materials and Methods

The top 10 most read daily UK newspapers (The Sun, Daily Mail, The Daily Mirror, The Telegraph, The Times, Daily Express, Daily Star, The Guardian, The Independent and the Financial Times) were searched for articles on the most prevalent 10 UK cancers (Table 1) via their on-line search facilities.14,15 The number of articles over a 12-month period was recorded. Where it was not possible to search via the newspaper’s online facility (The Independent and The Daily Mirror) a request for information was sent to the webmaster (although no answer was received). The combined estimated daily circulation of these newspapers is 25.3 million, i.e. 41% UK population.14–16

Table 1.

The prevalence of each of the most common UK cancers15

| Cancer | Prevalence (% population) |

|---|---|

| Breast | 15.6 |

| Lung | 13.3 |

| Colorectal | 12.8 |

| Prostate | 12.1 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 3.6 |

| Melanoma | 3.6 |

| Bladder | 3.5 |

| Kidney | 2.7 |

| Oesophagus | 2.7 |

| Stomach | 2.6 |

Results

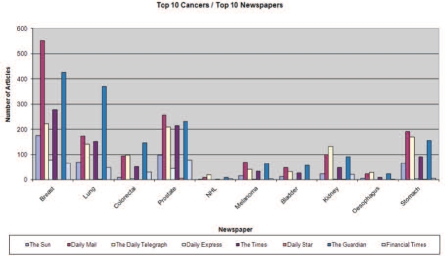

A total of 5832 articles relating to the top 10 most prevalent cancers in the UK were identified between 1 January 2009 and 31 December (Fig. 1). Breast cancer received the most media coverage (1797 articles), followed by prostate (1136 articles) and colorectal cancer (953). The malignancies that had the lowest media profile were non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (46 articles) and oesophageal (92 articles). The 10 most prevalent UK cancers account for 72.39% of all cases.15 The overall proportionality of these cancers was calculated and a ratio of articles to prevalence calculated (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

The number of articles reported by the print media related to the top 10 most common UK cancers.

Figure 2.

The proportion of articles on each cancer type relative to their prevalence.

Figure 2 shows that breast, kidney and stomach cancer are over-represented in the media, whilst the rest are under-represented. There is marked over-reportage of breast and stomach cancer in the tabloids compared to broadsheets. There is a slight over-representation of melanoma by the tabloids, which contrasts to an under-representation by broadsheets. There is comparable expression for the other malignancies between the newspaper types.

Discussion

Any strategy to improve public awareness of cancer should be applauded as it may improve patient outcomes. The media is regarded as one of the most important sources of patient information, potentially because it is easily accessible and the public is exposed to it passively.6,7,9,13 However, the reportage on health issues is not regulated by any medical representatives, but rather on what is deemed ‘newsworthy’ and what is likely to be of interest to the public.17

Our results have shown that there is a discrepancy between the number of articles on certain cancers and their associated prevalence. Analysis of articles mentioning stomach cancer revealed that not all of the reportage related to true disease; thus, these articles may have been tagged incorrectly (false positives – the correct reportage is likely to be less). For breast and kidney cancer, there does seem to be a true over-expression by the media. Breast cancer has a very high profile and has many fund-raising events that are covered by the media (e.g. ‘Fun runs’). In addition, celebrities have also raised the awareness of the disease (e.g. Kylie Minogue).10 To a lesser extent, the reportage of prostatic cancer may have been augmented by mentions of Mr al-Megrahi, the convicted Lockerbie bomber who was transferred from Scotland to Libya on compassionate grounds.

In terms of under-representation, the most notable cancer is colorectal cancer, which is the second most common cancer in men and women. A potential reason for this may be the ‘taboo’ associated with the disease and its symptoms – faeces, rectal bleeding and bowel habit are perhaps not the basis for a successful newspaper headline.5 However, there should be celebrity illness articles given the incidence of the disease. Taboos may also affect the overall reportage of cancer in the media – many people feel uneasy about this disease and thus the print media may under report articles about cancer in order not to alienate their readership. Full analysis of the scope of each article was not possible given the numbers involved, and this paper did not aim to assess the content and accuracy of each article, but purely record how often some cancers were mentioned by the print media. It is possible that certain medical terms are edited out by the print media, but this should not affect our results as ‘cancer’ is a term that is used by the public.9

Although no studies have assessed how the media profile affects perceptions directly, it can be postulated that the general public will have more understanding of diseases which receive a large amount of media coverage. In addition, cancers with a large media profile may be assumed to be more prevalent than they truly are. The converse is also likely to be true, with under-reported malignancies thought to be less common than they are. The scope for utilising the media to improve patient education should not be underestimated. Increased reportage of cancer may reduce the embarrassment attached to some malignancies and their associated symptoms in addition to breaking down their taboos.3,18 In addition to the number of articles, publications highlighting ‘red-flag’ symptoms of common malignancies may encourage patients to present to their GPs at an earlier point in their disease, which could improve overall cancer survival.1,3 Improved patient presentation could also be achieved by improving the perception of cancer.4,5,18 This would have the additional benefits of lessening the isolation felt by cancer patients and giving some positivity and hope.4,5,18 Reportage could also focus on patients’ experiences of cancer and their treatments, which could give the population more realistic expectations of therapy.18

How this enhanced reportage could be achieved is a matter of debate. The first stage is to highlight the benefits of media coverage and how it can be improved. From this point, additional strategies need to be envisioned. As health professionals, we are well versed in writing medical literature – journal articles, text books and patient information leaflets – but perhaps have less experience writing informative pieces for the media. Health journalists, however, are skilled at writing informative articles that are easily understood by the general population, but may lack some clinical insight into disease. Collaboration between healthcare professionals and journalists could result in articles that are relevant to the population, informative and in a style and format that is easily comprehendible to the lay public.9 Professional bodies, such as the Department of Health, the NHS, the Royal Colleges or the Royal Society of Medicine could release articles or information directly to newspapers. This may improve the quality of relevant medical information provided in newspaper articles. An additional method to enhance the educational content of these articles could focus on targeted advertising – this strategy could ensure that all articles containing cancer had a relevant ‘red-flag’ symptom box next to them. This advertising box could be funded by the relevant cancer charity and also include sources of further information.

These policies of media advocacy could ensure better representation of cancer and could run in partnership with existing public health strategies – screening, public information campaigns and the cancer ‘two-week wait’ – to improve cancer detection, and improve outcomes.

Conclusions

While newspapers do not exist as a health promotion platform, any mention of medical conditions will raise the overall consciousness and understanding of the population. In terms of cancer, coverage may have an affect on when patients present to their GPs and thus could improve overall cancer survival. Enhanced media coverage may also lessen the stigma of cancer and reduce any taboos associated with symptoms. A policy of media advocacy, where healthcare professionals take more of an active role in what is written by the print media, could further enhance the benefits of this under-utilised resource.

References

- 1.Adlard JW, Hume MJ. Cancer knowledge of the general pubic in the United Kingdom: survey in a primary care setting and review of the literature. Clin Oncol. 2003;15:174–80. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(02)00416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones R, Rubin G, Hungin P. Is the two week rule for cancer referrals working? BMJ. 2001;322:1555–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Nooijer J, Lechner L, de Vries H. A qualitative study on detecting cancer symptoms and seeking medical help; an application of Andersen’s model of total patient delay. Patient Educ Counsel. 2001;42:145–57. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macleod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, Macdonald S, Ramirez AJ. Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: evidence for common cancers. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:S92–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koller M, Kussman J, Lorenz W, Jenkins M, Voss M, et al. Symptom reporting in cancer patients: the role of negative affect and experienced social stigma. Cancer. 1996;77:983–95. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960301)77:5<983::aid-cncr27>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma SP. Media’s influence extends to cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1424–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwitzer G, Mudur G, Henry D, Wilson A, Goozner M, et al. What are the roles and responsibilities of the media in disseminating health information? PLoS Med. 2005;2:576–82. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman S, McLeod K, Wakefield M, Holding S. Impact of celebrity illness on breast cancer screening: Kylie Minogue’s breast cancer diagnosis. Med J Aust. 2005;183:247–50. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson J, Hocken D. How much vascular disease is reported by the UK media? Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1167–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The PLoS Medicine Editors. False hopes, unwarranted fears: the trouble with medical news stories. PLoS Med. 2008;5:681–3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holder HD, Treno AJ. Media advocacy in community prevention: news as a means to advance policy change. Addiction. 1997;92:S189–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williamson JML, Martin AG. Analysis of patient information leaflets provided by a district general hospital by the Flesch and Flesch–Kincaid method. Int J Clin Pract. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02408.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durrant R, Wakefield M, McLeod K, Clegg-Smith K, Chapman S. Tobacco in the news: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues in Australia, 2001. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:ii75–81. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Readership Survey. NRS readership estimates – Newspapers and supplements. October 2008–September 2009. < http://www.nrs.co.uk/toplinereadership.html> [accessed November 2009]

- 15. Office for National Statistics. Press release: UK population grows to 61.4 million. < www.statistics.gov> [downloaded September 2009]

- 16. Cancer Research UK. Cancer Incidence Statistics. < http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/index.htm> [accessed May 2010]

- 17.Cassels A. Media doctor prognosis for health journalism. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172:456. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muzzin LJ, Anderson NJ, Figueredo AT, Gudelis SO. The experience of cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1201–8. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]