Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The UK has a higher mortality for colon cancer than the European average. The UK Government introduced a 2-week referral target for patients with colorectal symptoms meeting certain criteria and 62-day target for the delivery of treatment from the date of referral for those patients diagnosed with cancer. Hospitals are expected to meet 100% and 95% of these targets, respectively; therefore, an efficient and effective patient pathway is required to deliver diagnosis and treatment within this period. It is suggested that ‘straight-to-test’ will help this process and we have examined our implementation of ‘straight-to-colonoscopy’ as a method of achieving this aim.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We carried out a retrospective audit of 317 patients referred under the 2-week rule over a 1-year period between October 2004 and September 2005 and were eligible for ‘straight-to-colonoscopy'. Demographic data, appropriateness of referral and colonoscopy findings were obtained. The cost effectiveness and impact on waiting period were also analysed.

RESULTS

A total of 317 patients were seen within 2 weeks. Cancer was found in 23 patients and all were treated within 62 days. Forty-four patients were determined by the specialist to have been referred inappropriately because they did not meet NICE referral guidelines. No cancer was found in any of the inappropriate referrals. The use of straight-to-test colonoscopy lead to cost savings of £26,176 (£82.57/patient) in this group compared to standard practice. There was no increase in waiting times.

CONCLUSIONS

Straight-to-colonoscopy for urgent suspected cancer referrals is a safe, feasible and cost-effective method for delivery of the 62-day target and did not lead to increase in the endoscopy waiting list.

Keywords: Urgent suspected cancer, Straight to test, Colonoscopy

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in England and Wales with approximately 1 in 20 patients developing colorectal cancer during their life-time.1

The EUROCARE-2 study in 19992 found that the mortality rate in UK was higher than other European countries and this was thought to be in part due to more advanced disease as a result of delay in treatment.3 To overcome this, the Department of Health (DH) introduced a white paper The new NHS – Modern, Dependable which guaranteed that everyone with suspected cancer will be seen by a specialist within 2 weeks of referral by their general practitioner (GP) and will undergo diagnosis and treatment of their cancer within 62 days of the original referral. To help GPs refer appropriate cases without overloading the system, guidelines were compiled in 20004 and these have been updated by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Ecellence (NICE) in 2006.5 The aim of these new cancer targets was to reduce the death rates by 20% in people under the age of 75 years by 2010.

Unfortunately, these targets were very difficult to meet by current colorectal services. In October 2004, a national meeting noted that the 62-day target was met in only 53% of the referrals and, as a result, devised the Belfry Plan6 which recommended 10 service improvement themes. ‘Straight-to-test’ is a principal component of the plan whereby suitable patients are sent for diagnostic testing directly prior to their out-patient appointment. In colorectal surgery, various groups implemented the ‘straight-to-test’ differently and offered flexible sigmoidoscopy or barium enema directly to either all or some of the suspected cancers referred by GPs. These groups had concerns about use of colonoscopy as the diagnostic tool for ‘straight-to-test', even though it is the gold standard for diagnosis of colorectal symptoms because it is argued that it is a time consuming, expensive and not widely available resource compared to other tests. A recent study by Aljarabah et al.7 has also expressed concerns about the ‘straight-to-test’ pathway.

Mayday University Hospital is a major acute district general hospital serving a population of 337,000 and has been offering ‘straight-to-colonoscopy” since January 2003 and well before the Belfry Plan. We, therefore, decided to study this aspect of our practice in detail, look at its safety, impact on waiting lists and finally perform cost-benefit analysis compared with previous pathway.

Patients and Methods

Straight-to-colonoscopy pathway

Patients presenting to their GP with lower gastrointestinal symptoms are assessed based on five standardised qualifying criteria laid down by the DH and NICE (Table 1). A pro-forma is then completed and faxed to the central cancer office at the Mayday Hospital.

Table 1.

Symptom score allocated to each of the five nationally accepted referral criteria

| 5 | Lower GI cancers |

|---|---|

| 5.1 | Rectal bleeding and a change in bowel habit to looser stools and/or increased frequency of defecation persistent for at least 6 weeks |

| 5.2 | Rectal bleeding persistently without anal symptoms over 60 years of age with no obvious external evidence of benign anal disease |

| 5.3 | Change of bowel habit of recent onset to looser stools and/or increased frequency. Of defecation, persistent for more than 6 weeks |

| 5.4 | Iron deficiency anaemia with out an obvious cause (Hb < 11 g/dl in men or < 10 g/dl in postmenopausal women) |

| 5.5 | An easily palpable abdominal or intraluminal rectal mass |

Patients are then contacted and offered a choice of dates to attend the endoscopy unit for a colonoscopy within 2 weeks to meet the 2-week rule. They are also sent full bowel preparation with instructions and information about colonoscopy. On the day of the test, they have a very brief consultation with a surgical endoscopist followed by colonoscopy (if appropriate). The consultation took the form of a brief history taking based on the symptom criteria and ascertainment of the patient's suitability for colonoscopy.

After the test, patients are either offered an out-patient appointment within 2 weeks for follow-up if appropriate or discharged back to their GP if the colonoscopy is normal or if there is benign self-limiting disease such as uncomplicated diverticular disease and haemorrhoids. Patients found to have suspicious lesions are spoken to on the day by a Macmillan Nurse, staging investigations requested and discussion at multidisciplinary meeting arranged within 2 weeks. The patients are then brought back to communicate the outcome of the multidisciplinary meeting either on the same day or the following day.

Data collection

This was performed retrospectively on all patients referred under the 2-week rule with suspected lower gastrointestinal cancers to the central referral point in the Cancer Office at the Mayday Hospital between October 2004 and September 2005.

A pro-forma was used to record all relevant data including demographic details, date of referral and date of colonoscopy, colonoscopy findings and time to diagnosis and treatment from the date of referral. The qualifying referral criteria (Table 1) from the GP were also recorded. The qualifying referral criterion was assessed by the specialist at the time of colonoscopy via a focused history taken as part of the routine assessment at the time of colonoscopy.

Cost effectiveness

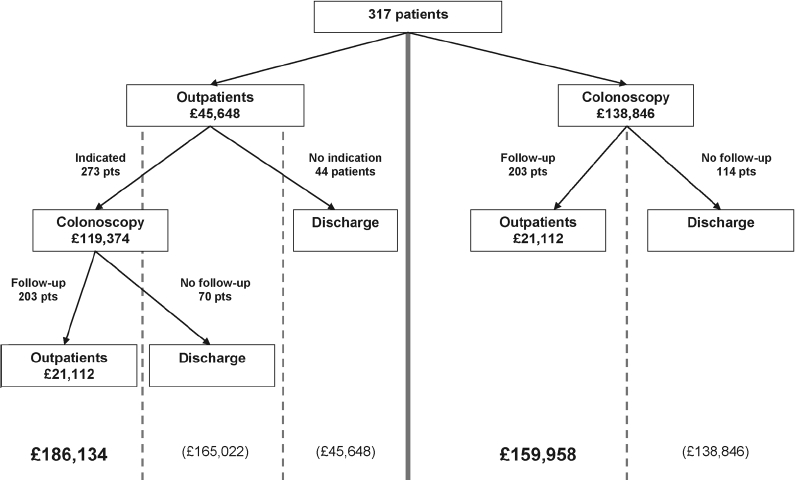

We analysed the cost effectiveness of use of colonoscopy as a straight-to-test tool by constructing a cost-effectiveness pathway tree (Fig. 1). The tree was subdivided into patients undergoing the ‘straight-to-colonoscopy’ pathway and those undergoing the traditional pathway. The completion point of the pathway was either at the out-patient appointment after the diagnosis was made at colonoscopy or at discharge. Final cost outcomes are shown at the bottom of each patient path and were based on the current NHS tariff for out-patient colonoscopy.

Figure 1.

Total costs of patients following straight-to-colonoscopy pathway.

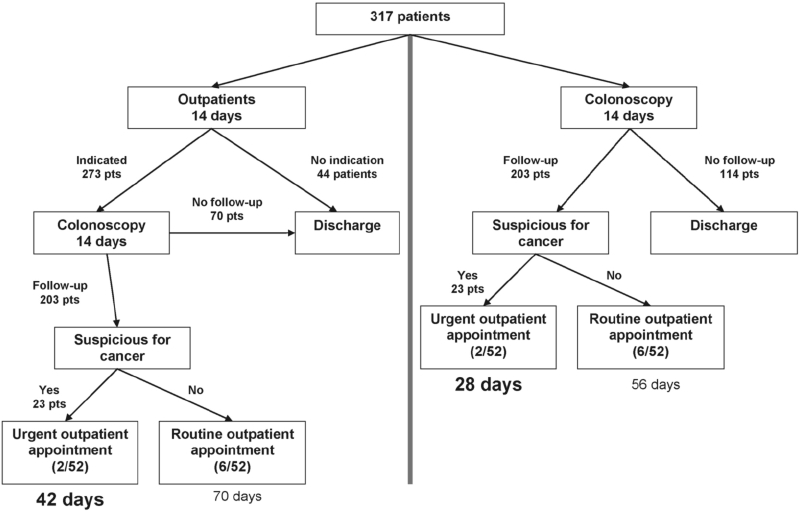

A decision pathway tree (Fig. 2) was constructed comparing time taken to progress in the ‘straight-to-test’ pathway versus the conventional pathway. The completion point was set at the out-patient appointment made after the initial colonoscopy. All patients were offered a colonoscopy with 14 days. In patients who had a suspected cancer at colonoscopy, an out-patient appointment within 2 weeks was offered, whereas patients with non-cancerous pathology (diverticular disease, benign polyps and diverticular strictures) were given a routine 6-week appointment. For the analysis, a worst case scenario of a maximum 2 or 6 week wait was assumed.

Figure 2.

Total time of patients undergoing straight-to-test pathway.

Impact on waiting list

We studied the impact of straight-to-test (colonoscopy) on the routine colonoscopy waiting list. Routine colonoscopy in this study is defined as colonoscopy in patients with probable non-malignant disease such as inflammatory bowel disease or for follow-up colonoscopy in patients undergoing surveillance for benign colonic polyps.

In order to do this, we examined the time interval between the referral date and the routine colonoscopy date, for 2 years before and after 2003, when straight-to-colonoscopy was introduced. The change in mean waiting time was assessed by an unpaired t-test (assuming normally distributed population) performed on SPSS v12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The null hypothesis was defined that there was no significant difference between the mean wait between the two groups.

Results

A total of 317 patients (131 males and 186 females) were seen during this 1-year period. The mean age was 66 years (range, 30-100 years). Two hundred and ninety eight out of 317 (94%) patients were seen within 2 weeks. Of 19 patients (5.9%) that were not seen, 18 re-arranged their appointment to an alternative date after agreeing an initial date within the 2-week target. One patient did not have a colonoscopy at the initial appointment and requested instead an out-patient appointment.

The two commonest reasons for referral as assessed by the GPs was the presence of a rectal mass and a change in bowel habit (Table 2). When assessed by the colonoscopist, the commonest referral criterion met was change in bowel habit for at least 6 weeks. We found that 44 of 317 (13.9%) patients referred did not meet any of the criteria for urgent colonoscopy when assessed by the colonoscopist. It was felt that GPs may have misinterpreted the guidelines but the patients had symptoms to warrant referral and investigation.

Table 2.

Analysis of the symptom score as scored by the GP and the specialist

| Scores | GPs | Specialists |

|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | 35/317 (11.0%) | 55/317 (17.4%) |

| 5.2 | 13/317 (4.1%) | 27/317 (8.5%) |

| 5.3 | 105/317 (33.1%) | 158/317 (49.8%) |

| 5.4 | 46/317 (14.5%) | 16/317 (5.0%) |

| 5.5 | 107/317 (33.8%) | 17/317 (5.4%) |

| Not marked/other | 11/317(3.5%) | 0/317 (0%) |

| Did not meet guidelines | 0/317 (0%) | 44(13.9%) |

The commonest finding at colonoscopy (Table 3) was a normal examination (112/317; 35.3%), followed by diverticular disease (69/317; 21.8%). In the group of patients that did not meet the referral guidelines, no cancerous lesions were found. The colonoscopy findings in these patients are summarised in Table 4.

Table 3.

Colonoscopy findings

| Finding | Number | Site | Histopathology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 23/317 (7.3%) | Sigmoid colon: 2 | Adenocarcinoma: 23/23 |

| Rectum: 19 | |||

| Ascending: 2 | |||

| Diverticulosis | 81/317 (25.6%) | Sigmoid: 61 | |

| Segmental, excluding rectum: 18 | |||

| Pancolonic: 2 | |||

| Polyp | 57/317 (18.0%) | 37 hyperplastic | |

| 20 adenomatous | |||

| Normal | 112/317(35.3%) | 90 Normal | |

| 22 serial biopsies | Normal | ||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 20/317 (6.3%) | 16 active chronic inflammation | |

| 2 ulcerative colitis | |||

| 2 collagenous colitis | |||

| Incomplete colonoscopy | 2/317 (0.6%) | Excessive looping | |

| Stricture | 6/317 (1.9%) | Descending colon: 2 | Benign inflammatory: 6/6 |

| Sigmoid colon: 4 | |||

| Haemorrhoids | 24/317 (7.6%) | ||

| Diverticulosis and inflammatory bowel disease | 4/317 (1.2%) | Sigmoid colon & rectum: 2 | |

| Descending & sigmoid colon: 2 |

Table 4.

Colonoscopy findings in inappropriate referrals

| Colonoscopy findings | Number |

|---|---|

| Cancer | 0/44 (0%) |

| Polyp | 4/44 (9.2%) |

| Diverticulosis | 11/44 (25.0%) |

| Normal | 25/44 (56.8%) |

| Haemorrhoids | 2/44 (4.5%) |

| Diverticulosis and polyp | 2/44 (4.5%) |

The completion rate for colonoscopy in this study was 97.4% (309/317 patients). Two patients had excessive looping of the bowel making colonoscopy uncomfortable and the procedure was terminated, and 6 had impassable colonic strictures. These patients were followed up via a barium enema examination for completion. The strictures were found to be benign diverticular strictures; in the patients in whom the examination was terminated due to excessive looping, barium enema examination was normal. There were no reported incidences of perforation in our study group.

Impact on cost

The NHS tariff for a new out-patient consultation in colorectal surgery in 2004-2005 was £144.00 per patient. The tariff for colonoscopy in 2004-2005 was £438.009 per colonoscopy per patient.

Using the pathway analysis tree in Figure 1, if a ‘straight-to-colonoscopy’ approach is adopted for all patients presenting under the urgent suspected cancer pathway, the total cost for the 317 patients in this study is £159,958.

Using intention-to-treat, if patients are given an outpatient appointment first, and then assessed for need for colonoscopy using the referral criteria, 44 patients will not be sent for a colonoscopy immediately but will have required an investigation of the bowel and probably would have been put on a waiting list for either a colonoscopy or a barium enema. Of the remaining 273 patients, 70 patients have ‘normal’ colonoscopy findings and are discharged. The remaining 203 are then offered a routine clinic appointment. The total cost for this arm of the tree is £186,134, a cost increase compared to ‘straight-to-colonoscopy’ of £26,176. In the two patients who had barium enema examinations because of incomplete colonoscopy, the cost of this was part of the tariff cost for colonoscopy.

Impact on delay

All patients requiring a ‘straight-to-test’ colonoscopy were offered an appointment with 14 days. All patients who followed the conventional ‘urgent suspected cancer’ pathway were also offered appointments within 14 days. In the group of patients following the ‘straight-to-test’ arm of the tree, patients attended their post-test out-patient appointment at a maximum of 28 days after the date of referral, leaving 34 days for the patient to undergo definitive treatment.

In the group of patients following the conventional ‘urgent suspected cancer’ arm, patients attended their post-test out-patient appointment at a maximum of 42 days after the date of referral, leaving 20 days for the patient to undergo definitive treatment.

Impact on waiting list

There was a reduction of 166.6 days (P < 0.01) in the mean waiting time from referral to colonoscopy (Table 5) after the introduction of straight-to-test colonoscopy.

Table 5.

Interval between referral and colonoscopy

| Status year | Patients (n) | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| 2001-02 | 4305 | 311.3 |

| 2003-04 | 3896 | 144.7 |

| Difference | 166.7* |

Difference in mean (311.3-144.7 = 166.6) P < 0.001 independent t-test.

Discussion

Cancer survival rates are poor in Britain when compared to Western Europe.8 It has been suggested that this is due to delay in diagnosis and treatment.3 It has been reported that a third of the delays in treatment occur before GP referral and that delay in every step of the treatment pathway adds to the mortality.9 It is now commonly accepted that the interval between presentation and diagnosis/treatment of colorectal cancer should be as short as possible, as recommended by the Association of Coloproctology10 and the NHS Cancer Plan.11 However, there is lack of consensus as to how best this can be achieved.

We have shown that use of colonoscopy as the diagnostic tool for the ‘straight-to-test’ practice is not only feasible but is also cost effective saving the NHS considerable sums that are used on unnecessary first out-patient appointments to triage these patients and also follow-up appointments because definitive diagnosis is made early enabling prompt discharge from secondary care back to primary care. The safety profile of the straight-to-test pathway is also good, with high completion rates and low perforation rates which compare well with suggested guidelines.12

One potential weakness of our study is the use of NHS tariffs for procedures and consultations as a marker for overall cost. Also, the small numbers of patients in our study are another potential weakness and may be due to fact that as observed in other studies7 a proportion of our cancer patients may present via alternate pathways to the straight-to-test pathway.

The observed rate of normal examinations is also lower than expected. This is because patients were categorised as having abnormal examinations if hyperplastic polyps were found. This is because of the relatively new finding that serrated polyps (which have an increased risk of malignancy) may be incorrectly classified as hyperplastic polyps.13 This study also classified diverticular disease as an abnormal examination finding, as simple diverticular disease may progress to a disease with significant morbidity and mortality, especially if patients present initially with diverticulitis type symptoms.14

It can also be argued that open access to colonoscopy readily will increase the waiting list. We have shown that this does not occur in our study since our waiting times for a colonoscopy has in fact got significantly shorter. We cannot suggest that the reduction in waiting times is as a result of solely adopting the straight-to-colonoscopy pathway but is primarily due to adopting endoscopy service improvement initiatives.

We have demonstrated that there are potential cost-savings with the straight-to-test pathway. It could be suggested that this is, in part, because the initial out-patient consultation does not take place; instead, a brief consultation takes place before colonoscopy is carried out in the endoscopy unit. We argue that this consultation does not add unnecessary delay to the procedure as the bulk of the assessment has already been carried out in general practice to defined guidelines and the cost of this consultation is absorbed into the tariff cost for colonoscopy.

An important consequence of this study is that 44 patients out of 317 referred (13.9%) were felt by the specialist assessment that the patient did not meet the DH referral criteria. However, these patients had symptoms requiring referral to secondary care for investigation and management. In the conventional system, they would have been referred by a letter or choose-and-book system into one of the colorectal clinics, underwent consultations and in our opinion would have eventually required some form of investigation depending on specialist preferences.

We detected some form of benign pathology in 19 of these 44 (43.1%) patients. We feel that these patients benefited from a diagnosis and early discharge from secondary care as opposed to the delay that would have happened had they been referred via the normal route.

Conclusions

The use of colonoscopy as ‘straight-to-test’ tool in our study group is feasible, safe and cost effective. It allows early detection of cancers and treatment of patient within UK Government targets. Even in patients without cancers, it allows prompt diagnosis, management of their conditions and early discharge to primary care. With 18-week target due to come into effect in 2009 and the 2-week target for seeing all referrals with colorectal symptoms looming, we feel that radical steps need to be taken to achieve this and straight-to-colonoscopy is one approach that should be considered in a newly designed colorectal service.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Christophe Fernandez for his input and analysis of the data. ADB currently receives funding from the Mason Medical Research Foundation, the Peel Medical Research Trust and Cancer Research UK.

References

- 1.Taskila T, Wilson S, Damery S, Roalfe A, Redman V, et al. Factors affecting attitudes toward colorectal cancer screening in the primary care population. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:250–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Survival of Cancer Patients in Europe: The EUROCARE-2 study. I ARC Sci Publ. 1999;151:1–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones R, Rubin G, Hungin P. Is the two week rule for cancer referrals working? BMJ. 2001;322:1555–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. Referral guidelines for suspected cancer. London: DH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Referral for suspected cancer: NICE guideline CG27. < http://www.nice.org.uk/CG27>.

- 6.The Belfry Plan. 2002. < http://www.cancerimprovement.nhs.uk/%5Cdocuments%5Cbowel%5CBelfry_Plan.pdf>.

- 7.Aljarabah MM, Borley NR, Goodman AJ, Wheeler JMD. Referral letters for 2- week wait suspected colorectal cancer do not allow a ‘straight-to-test’ pathway. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:106–9. doi: 10.1308/003588409X359114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp D. Trends in cancer survival in England and Wales. Lancet. 1999;353:1437–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baig M, Whatley P, Thompson M. Delay during stages of referral, diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer: their relationship to mortality. Gut. 1999;44(Suppl 1) 16 (T62) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for the Management of Colorectal Cancer. London: ACGBI; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. The NHS Cancer Plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: DH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowles CJ, Leicester R, Romaya C, Swarbrick E, Williams CB, Epstein O. A prospective study of colonoscopy practice in the UK today: are we adequately prepared for national colorectal cancer screening tomorrow? Gut. 2004;53:277–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.016436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makinen MJ. Colorectal serrated adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2007;50:131–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salem TA, Molloy RG, O'Dwyer PJ. Prospective, five-year follow-up study of patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1460–4. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]