Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The results of a survey on evidence-based surgery (EBS) among members of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) are presented. The study also analyzes the citations earned by articles with different levels of evidence (LOE) to see if LOE have any bearing on the importance attached to the articles by authors and contributors to the journals.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The questionnaire was e-mailed to 1000 randomly chosen consultant orthopaedic surgeons who were members of either the AAOS or the BOA. Participants were provided with the option of responding through web-based entry. For citation analysis, citation data were gathered from the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American volume) between the years 2003 and 2007 (5-year period).

RESULTS

The survey showed that awareness and access to EBS have improved greatly over the years. At the present time, these factors are not important barriers to the implementation of EBS in clinical practice in developed countries. There was a statistically significant difference in those with and without additional qualifications with regard to the approach to EBS. However, an equal percentage of surgeons with and without additional qualifications felt that it was difficult to adhere to EBS guidelines in daily clinical practice. Citation analysis showed that readers of professional journals attach importance to LOE category of the article and tend to cite level-I evidence articles more than other articles.

Keywords: Evidence-based medicine, Evidence-based surgery, Evidence-based orthopaedic surgery, Levels of evidence, Citation rates

Advocates of evidence-based surgery (EBS) seem to be certain that it is a pragmatic concept that ought to be universally embraced for the benefit of both patients and orthopaedic science in general.1 Many beliefs and customs exist in orthopaedic surgery for which there is not much evidence.2 Sackett et al.3 defined evidence-based medicine as ‘the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients'. To make such use of available evidence, it is important to be able to assess the available information critically. Surgeons do not seem to implement new evidence immediately (especially those involving new procedures), even if it is available. They prefer to wait for trusted and influential leaders in the community to pronounce their verdict about the new knowledge.4 Levels of evidence were thought to help busy orthopaedic surgeons acquire the most relevant valid information in the shortest possible time and with the least possible effort.5

Subjects and Methods

This was a ‘cross-sectional’ survey among 1000 randomly selected members of American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA). A questionnaire was designed, partly based on the patterns of the questionnaires used for earlier surveys on evidence-based practice in the specialty of orthopaedics and in other branches of medicine.6-10 The survey focused on access, practical applicability, future concerns and the attitude towards EBS. The questionnaire was in a single web page containing 31 items. Details of the survey design are given in Table 1. AAOS and BOA were selected as they include a large number of orthopaedic surgeons who are familiar with EBS. The e-mail addresses were obtained from the AAOS and BOA directory of members.

Table 1.

Parameters included in survey design

| Parameters | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Log file analysis | * | |

| Unique site visitor identification (using Traffic backend stat counter) | * | |

| Incentive for participation | * | |

| Screening by institutional review board | * | |

| Pre-testing of questionnaire | * | |

| Adaptive questioning | * | |

| Completeness check (using My SQL database) | * | |

| Randomisation of items in questionnaire | * | |

| Use of online survey generator | * | |

| Randomisation of participants (computer generated random numbers) | * | |

| Prior consent from participants | * | |

| Advertisement regarding survey | * | |

| Data protection | * | |

| Neutral response option | * | |

| Review of response (prior to submission) | * |

This was a double-blind survey done by a software professional without any involvement in the study. The questionnaire was e-mailed directly to the participants and provision was made for web-based entry (<http://www.ebossurvey.com>). Data were collected over 6 months from the date of first mailing. Subsequent to first mailing, four reminders were sent at intervals of 4 weeks. Participation was voluntary. The purpose of the survey was explained to the participants. The web-site was designed such that multiple entries from a single responder (single IP address) was not possible. The survey has been reported according to the ‘CHERRIES statement’ on web-based surveys.11

Citations are regarded as indicators of the significance and relevance of articles following publication.12,13 Evidence-based classification of an article can be considered as a tool to assess the quality of the article prior to publication in the journal. The electronic version of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American volume) publishes citation data along with the articles and citations were counted using that data base. To exclude the effect of journal self-citations, citation rates were also calculated after excluding self-citations. Levels of evidence was introduced in the J Bone Joint Surg Am in 2003 and we have gathered the citation data between 2003 and 2007 (5-year period), allowing a minimum of 2.5 years for accumulation of citations for articles published in 2007.

Results

Results of the survey

A total of 658 orthopaedic surgeons responded (response rate of 65.8%) and the responses were complete in 94% of questionnaires. Of respondents, 82.3% were in the age group 36-65 years and 65.8% were employed in non-teaching hospitals or in private practice with the remaining 34.2% in teaching hospitals. Of respondents, 18.3% had additional qualifications such as PhD or MPH, while the rest did not have additional qualifications that indicate higher research experience. The results of the significant aspects of the survey are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the overall results of the survey (values rounded to nearest whole number)

| Ignore the recommendations of new level-I evidence | 2% |

| Discuss with colleagues before adopting new level-I evidence | 12% |

| Reject article recommendation with low level of evidence | 14% |

| Never changed practice based on EBS recommendation | 17% |

| Always changed practice based on EBS recommendation | 18% |

| Had time for detailed reading of journals | 23% |

| Easy to adopt EBS guidelines in practice | 31% |

| EBS highly useful | 36% |

| Concerns about restriction of freedom as a clinician | 45% |

| Acceptance of article recommendation in spite of low level of evidence | 48% |

| EBS occasionally useful | 52% |

| Fully familiar with EBS | 53% |

| Comfortable doing online EBS search in the out-patient clinic | 62% |

| Comfortable with online EBS search during ward rounds | 63% |

| Concerned about patient insistence on treatment based on EBS | 64% |

| Difficult to adhere to EBS guidelines in practice | 69% |

| Concerned about potential for abuse of EBS by lawyers | 76% |

| Had time only for selective reading of journals | 77% |

| Impression about article influenced by level of evidence classification | 78% |

| Concerned that new treatment procedure may be denied funding citing low LOE | 79% |

| Concerned that research funding may be denied citing low LOE | 81% |

| Circumspect about financial conflict of interest even in level-I evidence | 82% |

| Feel that EBS culture should be promoted | 85% |

| Willing to alter practice immediately in accordance with new level-I evidence | 86% |

| Familiar with EBS concept | 92% |

| Had access to EBS literature | 99% |

For a few specific questions, we compared the responses of the participants as a whole with the responses of the participants with and without additional academic qualifications (PhD or MPH). The results are summarised in Table 3. In this study, it was assumed that possession of higher qualification was evidence of a higher degree of familiarity with research methodology in general. Of those with additional qualifications, 89.8% said that they were comfortable with the bio statistical vocabulary used in the journals as opposed to 72% of those without additional qualifications. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.00007, chi-square test). Of those with additional qualifications, 46% had received formal training in EBS literature search compared to 28% in the group without additional qualifications. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.000098). In the additional qualification group, 68.8% said that it was difficult to adhere to EBS guidelines in daily practice compared with 69.4% in the other group. The difference was statistically not significant (P = 0.7356). Interestingly, only 21.2% of those in the additional qualification group said that they would alter their practice immediately if the conclusion of a level-I study was different from their own experience. This is in contrast to the response of the overall group where 85.6% were ready to alter their practice immediately upon the recommendations of a level-I study. The difference was statistically significant. The vast majority in the additional qualification group preferred to discuss with their colleagues before altering their practice.

Table 3.

Comparison between additional qualification group and general group

| General group | Additional qualification group | |

|---|---|---|

| Comfort with bio-statistical vocabulary | 72% | 90% |

| Formal training in EBS literature search | 28% | 46% |

| Difficulty in adhering to EBS guidelines | 69% | 69% |

| Speed of response to level-I evidence | 86% | 21% |

Results of citation analysis

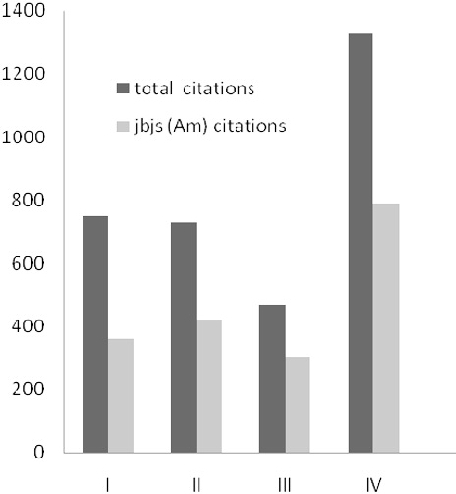

The data regarding the number of articles, total number of citations and citations after excluding journal self-citations are given in Figures 1 and 2. The average citations per article was 4.9 for level-I articles, 4.0 for level-II articles, 3.7 for level-III articles and 3.4 for level-IV articles. The average citation per article after excluding journal self-citations were 2.5 for level-I articles, 1.7 for level-II articles, 1.3 for level-III articles and 1.4 for level-IV articles. Journal self-citations were significantly higher in level II, III and IV categories (P < 0.001, chi-square test). In level I category, external citations were significantly higher (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Number of studies in each level of evidence per year between 2003 and 2007.

Figure 2.

Total citations and journal self-citations for each level of evidence.

Discussion

Criticisms of evidence-based medicine are largely based on epistemology and ethics. Epistemologically, it argued that the medical findings are often subject to subsequent dis-proval and the ‘evidence’ does not withstand the test of time.14-16 The quality of evidence is affected by the quality of research on which the evidence is based.17-19 There is insufficient evidence that implementation of EBM has led to better clinical outcome.18-20-23 Concerns have been expressed in the past regarding familiarity and ease of access to EBS literature and practical applicability of EBS. Ethical concerns include the use of evidence-based medicine to deny life-saving emergency services to areas which truly required them,24 loss of therapeutic freedom of the clinicians,25 denial of funding to clinical researchers on the grounds of lack of evidence,26 and exploitation of EBM data by pharmaceutical companies to market products aggressively.27 Our survey was designed to assess the prevalence of these concerns among surgeons. It was aimed at orthopaedic surgeons, but the results have relevance to other branches of surgery as well.

Results of the present survey indicate that the majority of orthopaedic surgeons (around 92%) had basic level of awareness of EBS. Also, 99% of surgeons had access to EBM literature; this is higher than earlier surveys.6,7,10 This indicates that access to EBM literature and web-based resources has improved over the years and cannot be considered as major impediments in the implementation of EBS. Supporters of EBS have suggested that surgeons should check the evidence on the web in their out-patient clinics and by the patient's bed side when deciding the best course of action. Hand-held devices were useful to provide surgeons with ‘real-time access’ to the internet when confronted with difficult clinical situations.28 In our survey, more than 60% of surgeons were willing to access the web for EBS literature in out-patient clinics or ward rounds. In the past, it was thought that doctors in peripheral hospitals may have had difficulty in accessing information regarding EBS.29 However, access to EBS information has improved. There was a statistically significant difference in the level of comfort with biostatistical vocabulary between those who had additional qualifications and research experience and those who did not. This could be partly due to the fact that significantly higher proportion of those with additional qualifications had received formal training in EBM. Of the participants in our survey, 85% felt that EBS should be promoted. Nearly 86% of surgeons said that they would change their practice based on level-I evidence whereas only around 47% said that they would do so on the basis of literature lesser than level-I evidence. This shows that level of evidence is considered important by a significant number of surgeons. The results are similar to those of previous surveys on evidence-based orthopaedic surgery.8-10

In spite of the enthusiasm for EBS, most surgeons (69%) felt that there are limitations to the application of EBS in practice. This is similar to the survey by Poolman et al.,9 wherein only 20% of the participants used EBM information in clinical decision making. Since familiarity and access to EBS are no longer major issues, efforts to improve the practical application of EBS should focus on formal training of surgeons in EBM methods. In the survey by Hanson et al.,8 90% of participants agreed that there was a need for training surgeons in research methodology. In our survey, 90% of participants with additional qualifications were comfortable with the biostatistical vocabulary when compared with 72%, who did not have additional qualification. Poolman et al.9 reported that younger age, possession of PhD degree and working in academic institutions were associated with better comprehension of EBS. In this survey, those in the additional qualification group were actually more reluctant than the overall group in incorporating the recommendations of a level-I study when their own experience was otherwise. Familiarity with the EBS methods may increase the awareness of its limitations too. Even when there is familiarity, access and formal training in EBM methods, it may be difficult to apply EBS to an individual patient due to socio-economic reasons, facilities available or due to the choice of treatment by the patient. EBM ignores the benefits of clinical experience.7 EBM recommendations apply to patient cohorts and may not resolve the dilemma of a clinician faced with an individual patient.32,33 In such situations, clinical judgement may be more appropriate than adhering to evidence-based guidelines.34

Attitudes of the authors towards levels of evidence can be gauged by analysing the citations. In the present study, average citation rate decreased from 4.9 per article for level-I articles to 3.4 per article for level-IV articles. Even when journal self-citations were discounted, the average citation rate for level-I articles (2.5/article) was still higher than the rate for level-IV articles (1.4/article). While there was no statistical significance between overall citation rates of articles belonging to different LOE categories, the difference between categories became highly statistically significant once journal self-citation rates were excluded from calculation. This suggests that level-I studies were considered important by contributors of other journals in the same or related fields. This is a positive trend in the EBS culture. We have not found similar data in the literature to compare our results. The drawback of using citation as a marker of the quality is that citation based metrics such as ‘impact factor’ have numerous limitations.30,31 More citations for articles with higher levels of evidence do not necessarily imply that the quality of the studies were very high. It is, perhaps, just a reflection of the perception of other authors about LOE.

Apprehensions regarding the possible abuse of EBS (by lawyers, patients and funding authorities) are present among majority of orthopaedic surgeons. Nearly 76% of the surgeons felt that EBS concept could be exploited by lawyers who may argue that patient was harmed by treatment based on lower levels of evidence. Around 64% felt that patients could become more demand treatment based on LOE. It remains to be seen whether these apprehensions translate into realities. Readers seem to be cautious in accepting the recommendations of even level-I studies in the presence of financial conflicts of interest. Nearly 82% of the respondents in our study stated that they would be circumspect regarding the recommendations of such studies even if the level of evidence is high. Commercial sponsors may exploit the clinicians’ implicit trust in evidence-based medicine to publish reports favourable to their products.27 Previous surveys have not addressed these issues but the issues are important enough to attract further studies. Over 80% felt that authorities could deny them research funding citing levels of evidence or restrict their choice of research topics. Some 45% felt that clinician's freedom in implementing treatment options may also be restricted. The responses received in our survey seem to add to the growing list of concerns regarding EBM in the recent times.

Conclusions

Is EBS going to be the hallowed ground supporting the edifice of surgical science in future? Or is it a pedantic trend that will make way for some other trend in the future? Time and further research hold the answers. However, studies including ours seem to indicate that most orthopaedic surgeons welcome the EBS culture and the level of awareness and access to EBS have improved significantly. Practical application seems to the key issue and this can probably improve with formal training. Our survey has brought to the attention of the community certain hitherto unaddressed concerns such as possible abuse of the EBS by lawyers and patient community. It has also shown that articles with high levels of evidence seem to enjoy a certain citation advantage. It remains to be seen whether these higher citations would eventually turn out to be sign-posts of high quality research.

References

- 1.Wright RW, Kuhn JE, Amendola A, Jones MH, Spindler KP. Symposium Integrating Evidence-Based Medicine into Clinical Practice. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:199–205. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tejwani NC, Immerman I. Myths and legends in orthopedic practice: are we all guilty? Clin Orthop. 2008;466:2861–72. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0458-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Hayes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996;312:71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Gray JA. Transforming evidence from research into practice: 4. Overcoming barriers to application (Editorial) ACP Journal Club. 1997;126:14–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurwitz SR, Slawson D, Shaunessey A. Orthopedic information mastery: applying evidence based information tools to improve patient outcomes while saving orthopedist's time. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:888–94. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200006000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McColl A, Smith H, White P, Field J. General practitioners’ perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316:361–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olatunbosun OA, Edouard L, Pierson RA. Physicians’ attitudes toward evidence based obstetric practice: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316:365–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanson BP, Bhandari M, Andige L, Helfet D. The need for education in evidence based orthopedics: an international survey of AO course participants. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75:328–32. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poolman RW, Sierevelt RN, Farrokhyar F, Mazel JA, Blankevoort L, Bhandari M. Perceptions and competence in evidence based medicine: are surgeons getting better? A questionnaire survey of members of the Dutch Orthopedic association. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:206–15. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldhahn S, Audigé L, Helfet DL, Hanson B. Pathways to evidence based knowledge in orthopedic surgery: an international survey of AO course participants. Int Orthop. 2005;29:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0617-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garfield E. Citation frequency as a measure of research activity and performance. Essays of an Information Scientist. 1973;1:406–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16569–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poynard T, Munteanu M, Ratziu V, Benhamon Y, Dimartino V, et al. Truth survival in clinical research: an evidence based requiem? Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:888–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-12-200206180-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little M. ‘Better than numbers ……. A gentle critique of evidence based medicine. Aust NZ J Surg. 2004;74:496. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2002.02563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devisch I, Murray SJ. We hold these truths to be self-evident: deconstructing 'evidence based’ medical practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:950–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers W, Ballantyne A. Justice in health research: what is the role of evidence based medicine? Perspect Biol Med. 2009;52:188–202. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hannes K, Aertgeerts B, Schapers R, Goedhuys J, Buntinx F. Evidence based medicine: a discussion of the most frequently occurring criticisms. Netherlands Tidjschrift Voor Geneeskunde. 2005;149:1983–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenicek M. Evidence based medicine: fifteen years later. Golem the good, the bad and the ugly in need of a review? Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2006;12:RA241–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worrall J. What evidence in evidence based medicine? Philos Sci. 2002;69:316–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howland RH. Limitations of evidence in the practice of evidence based medicine. J Psychol Nurs Mental Health Sci. 2007;45:13–6. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20071101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hö Izel D, Schubert-Fritschle G. Evidence based medicine in oncology: do the results of trials reflect clinical reality. Zentralblatt für Chirurgie. 2008;133:15–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1004669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerridge RK, Saul PW. The medical emergency team, evidence-based medicine and ethics. Med J Aust. 2003;179:313–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grahame-Smith D. Evidence based medicine: Socratic dissent. BMJ. 1995;310:1126. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6987.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saarni SI, Gylling HA. Evidence based medicine guidelines: a solution to rationing or politics disguised as science? J Med Ethics. 2004;30:171–5. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.003145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brody H, Miller FG, Bogdan-Louis E. Evidence based medicine: watching out for its friends. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48:570–84. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2005.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurwitz SR, Tornetta P., III An AOA critical issue, how to read the literature to change your practice: an evidence based medicine approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1873–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles A, Bentley P, Polychronis A, Grey J. Evidence based medicine: why all the fuss? This is why. J Eval Clin Pract. 1997;3:83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.1997.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seglen PO. Why the impact factor of journals should not be used for evaluating research. BMJ. 1997;314:498–502. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7079.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar M. The import of the impact factor: fallacies of citation dependent scientometry. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(Suppl):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stirrat GM. Ethics and evidence based surgery. J Med Ethics. 2004;30:160–5. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.007054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barratt A. Evidence based medicine and shared decision making: the challenge of getting both evidence and preferences into health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Black N. Evidence based surgery: a passing fad? World J Surg. 1999;23:789–93. doi: 10.1007/s002689900581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]