Abstract

Today’s students around the world are striking deals to buy and sell the drug methylphenidate (MPD) for cognitive enhancement. Our knowledge on the effects of MPD on the brain is very limited. The present study was designed to investigate the acute and chronic effect of MPD on the prefrontal cortex (PFC) neurons. On experimental day 1 (ED1) recordings were obtained following saline injections and after 2.5 mg/kg MPD. On ED2 through ED6, daily single 2.5 mg/kg MPD was given followed by 3 washout days (ED7 to 9). On ED10, neuronal recordings were resumed from the same animal after saline and MPD injection similar to that obtained at ED1. Ninety PFC units were recorded, all responded to the initial MPD injection, 66 units (73%) increased their activity At ED10. Recordings were resumed for the 66 units that increased their firing rate at ED1, and following MPD injection 54 units (82%) exhibited significant increases in their baseline firing rates compared to ED1 baseline. When these 54 units were rechallenged (chronic effect) with MPD, 39/54 (72%) exhibited reduction in their firing rate which can be interpreted as tolerance. From the 24 (27%) units that responded to MPD at ED1 by decreasing their activity, 14 units (58%) exhibited a decrease in their baseline firing rates at ED10 compared to ED1 baseline. However, following MPD rechallenge of these 14 units, 11 units (79%) exhibited an increase in their firing rate which is interpreted as sensitization. In conclusion, all PFC units modified their neural baseline activity.

Index words: Ritalin, neuronal activity, prefrontal cortex, freely behaving rats

1. Introduction

The psychostimulant (methylphenidate MPD) has become the most prescribed drug or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Eichlseder, 1985; Solanto, 1998; Swanson et al., 1999; Challman and Lipsky, 2000; Accardo and Blondis, 2001; Arnsten, 2006). It is estimated that 5 to 15% of the USA population between 5 and 18 years old is being treated with MPD (Anderson et al., 1987; Rowland et al., 2001; Barbaresi et al., 2002; Froehlich et al., 2007). MPD is a psychostimulant that has a chemical structure closely related to the structures of amphetamine and methamphetamine (Kallman and Isacc, 1975; Patrick and Markowitz, 1997; Teo et al., 2003). Both MPD and cocaine elicit their effect by binding to dopamine transporter (DAT) and preventing the reuptake of dopamine to the presynaptic terminal thereby increase the extracellular dopamine concentration in the synaptic cleft (Gatley et al., 1999; Volkow et al., 1995, 1999) as well as enhance dopamine release (Kuczenski and Segal, 1997; Segal and Kuczenski, 1997). Dopamine modulates prefrontal cortex (PFC) function through action of the dopamine, D1, and D2 family receptors (Arenstein, 2006). This area is the target of this study since it plays a prominent role in a complex neuronal system that serves to regulate cognitive performance and motor function (Goldman-Rakic, 1987) The PFC has an important role in attention regulation, inhibits responses to distracting stimuli and suppresses irrelevant thoughts (Wood and Grafman, 2003), as well as guides behavior and attention using working memory, applying representational knowledge to inhibit inappropriate actions, thoughts, and feelings (Anderson et al., 1999; Arnsten, 2006), and suggested to be one of the main central nervous system sites of MPD action (Yang et al., 2006a, b, c, d).

In previous behavioral and neurophysiological experiment using MPD dose response protocol, it was observed that acute low dose of MPD (0.6mg/kg i.p.) failed to elicit alteration in locomotion as well as sensory evoked responses while moderate MPD administration (2.5 mg/kg i.p.) elicits locomotor activation (Gaytan et al., 1997, 2000; Yang et al., 2000a, b, 2003, 2006a, 2007, 2010) and suppresses the sensory evoked responses recorded from the PFC (Yang et al., 2006b). Higher dose of MPD (10.0mg/kg i.p.) elicits further excitation on locomotion and further attenuation of the average sensory evoked responses in the PFC. Moreover, chronic MPD application elicits behavioral sensitization but causes further attenuation of the sensory evoked responses component following all the three MPD doses (0.6, 2.5, and 10.0 mg/kg i.p.) (Yang et al., 2006a, b, c, d, 2007). In a similar experimental procedure but instead of MPD, MDMA (Ecstasy) was administered and acceleration of the PFC average sensory evoked responses were observed (Atkins et al., 2009).

The objective of this study is to investigate the acute and the chronic effect of MPD on PFC single unit activity recorded from freely behaving animals previously implanted bilaterally with permanent electrodes. This study is critical since today, on university campuses around the world, students are striking deals to buy and sell prescription drugs such as MPD (Ritalin) (Greely et al., 2008).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 170–180g on the purchase day were each housed individually in the animal facility room with an ambient temperature of 21± 2°C and relative humidity of 58–64%: food pellets and water were provided ad libitum. The room was illuminated on a 12:12 light/dark circle (light on at 06:00). The initial 5–7 days were used for acclimation.

2.2 Electrode implantation

On the last day of acclimation period, the rat was weighed and anesthetized with 50mg/kg i.p. phenobarbital and placed into a sterotoxic instrument. The head was shaved and the head skinned and muscle was retracted from the cranium and bilateral holes of 0.5mm in diameter were drilled over the prefrontal cortex, 3.2mm anterior to Bregma, lateral 0.6mm from the midline using the coordinate derived from Paxinos and Watson (1986) atlas. Nichrom wire electrodes 60μm in diameter, insulated over their whole length except at the tip by Teflon were inserted into the holes 2.8mm below the skull aiming to be in the PFC area 3 i.e. cingulate cortex. Unit activity was monitored during electrode penetration using Grass P511 and its cathode follower. If at this location there was no spike activity with signal to noise ratio of at least 3:1, the electrodes were moved down in steps of about 5μm until they showed spike activity with good signal to noise ratio. Once good signal was obtained, the electrode was permanently fixed to the skull with dental acrylic cement and the second electrode in the other hemisphere was implanted in a similar way (Dafny et al., 1973, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1983; Dafny and Terkel, 1990; Yang et al., 2006b, c). The electrode leads were attached to an amphenol plug and the latter was cemented to the skull.

Rats were allowed to recover from the surgical procedure for 5 to 7 days. During this recovery time, every day for 2 to 3 hours, the rats were acclimated to the testing cage and were connected to Alpha Omega wireless transmitter located on the back of the animals which allowed the animals to move freely around the testing cage. The Alpha Omega transmitter digitized the neuronal activity and sent the signals to a receiver that connects to a PC that stores the data. Off line Alpha Omega software was used to sort the spike activity to evaluate the sorted spikes (single unit). Housing condition and experimental procedure were approved by our animal welfare committee. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. This study was conducted in accordance to the declaration of Helinski and approved by our institutional animal welfare committee.

2.3 Drugs

Vehicle injections consisted of 0.8cc isotonic saline solution (0.9% NaCl) was administered. Methylphenidate hydrochloride (MPD) was obtained from Mallinckrot (Hazelwood, MO). MPD was dissolved in a 0.9% isotonic saline solution and the 2.5mg/Kg MPD was calculated as a free base. All injections were given intra-peritoneally (i.p) and equalized to a volume of 0.8cc with 0.9% saline so that the volume of each injection was the same for all animals. In our previous MPD dose response experiments using behavioral and neurophysiological sensory evoked potential procedure, it was found that 2.5mg/kg i.p. was the dose that elicited behavioral and neurophysiological sensitization (Algahim et al., 2009; Gayton et al., 1996, 2000; Lee et al., 2009; Podet et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2000, 2003, 2006a, b, c, d, 2007, 2010). Therefore, this dose was selected for this single unit experiment.

2.4 Experimental Protocol

At experimental day 1 (ED1), animals were connected to the recording system and allowed 20–30 minutes. acclimation before the recording session. Saline was injected (0.9% in 0.8cc) and baseline neuronal recording for 30 minutes started immediately post the saline injection followed by 2.5mg/kg i.p. MPD injection and recording was resumed for an additional 120 minutes. From ED2 to ED6 rats were injected once a day in the morning with 2.5mg/kg MPD in the test cage. ED7 to ED9 were the washout days, i.e. no injections were given. At ED10, identical experiment as ED1 was performed with the neuronal recording following saline and following 2.5mg/kg MPD (see table 1). Similar experimental protocol was used previously (Yang et al, 2006a, b and c, 2007 c, 2010).

Table 1.

Experimental protocol

| Experimental day | 1 | 2–6 | 7–9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Saline | 2.5mg/kg | Washout | Saline |

| 2.5mg/kg | 2.5mg/kg |

On experimental day 1, neuronal recordings were performed after saline injection (baseline) for 30 minutes and continued for 120 minutes following 2.5mg/kg injection of MPD. Experimental days 2–6 rats were injected and recorded once a day in the morning with 2.5mg/kg MPD. Days 7–9 were washout days (drug abstinence). Neuronal recordings resumed on experimental day 10 after saline (baseline) and 2.5mg/kg MPD. Experimental day 1 and day 10 were treated with identical protocol.

2.5 Histological verification of electrode placement

At the conclusion of the recording at ED10, the rats were overdosed with sodium pentobarbital. A small lesion was produced at the tip of each of the electrodes by passing a 50μA DC current for 30s. The rat’s brain was transcardialy perfuse with 10% formalin solution containing 3% potassium ferrocyanide. Brain slices were cut serially at thickness of 40–60μ and histologically stained with Cresyl violet. The position of the electrode tip was identified by the location of the lesion and the Prussian blue spot using the Paximo and Watson (1986) Rat Brain Atlas.

2.6 Data Analysis

Spike Sorting

Off line spike sorting by Alpha Omega software was used. The Spike 2 version 7 software (Cambridge Electronics Design- CED) was used for spike sorting. The data was captured by the program and processed using low and high pass filters (0.3–3 kHz). 1000 waveform data points were used to define a spike to create. The spikes were extracted when the input signal enters the amplitude window (previously determined). Spikes with peak amplitude outside these limits were rejected. The algorithm that we used to capture a spike allows the extraction of templates that provide high-dimensional reference points that can be used to perform accurate spike sorting, despite the influence of noise, spurious threshold crossing and waveform overlap. All temporally displaced templates are compared with the selected spike event to find the best fitting template that yields the minimum residue variance. Secondly, a template matching procedure is then performed; when the distance between the template and waveform exceeds some threshold the waveforms are rejected. That means that the spike sorting accuracy in the reconstructed data is about 95%. All these parameters of spike sorting for each electrode were sorted and used for the activity recorded in experimental day 1 (ED1). On ED10 the templates from ED1 were then loaded onto ED10 data to be reclassified. This ensured that the spike amplitude and pattern from ED1 is the same spike on ED10. Based on the above we assume that the same spike was captured at ED1 and ED10.

Firing rates were evaluated for normality assumptions to determine parametric or non parametric methods to evaluate differences before and after treatment. We assessed differences in firing rates using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test because the normality assumption did not hold. Changes in firing rates spikes/sec were implemented across three times: (i) comparing firing rates between saline and MPD 2.5mg/kg in ED1; (ii) comparing firing rates differences between ED10 and ED1; and (iii) comparing firing rates between saline and MPD 2.5mg/kg in ED10. We reported the test statistic of the Wilcoxon signed rank tests and associated p-value. In addition, an analysis of variance for repeated measures was estimated to evaluate the effect of the subjects (rats), day effect and saline versus MPD 2.5 simultaneously, using compound symmetry as the covariance structure of the model and after transformation to reach the normality assumption using Box-Cox transformation. We used SAS 9.2 to calculate estimates. Statistical significance was determined using a type 1 error level of 0.05.

3. Results

Hundred and twenty one units were recorded, only ninety (90) units were exhibiting identical spike shape pattern on experimental day 1 (ED1) and on experimental day 10 (ED10) and were considered as recordings from the same unit. All the recordings were confirmed to be recorded from the PFC after the histological verification. Most of the PFC neurons exhibited low firing rates between 0.1 to 5 spikes per second, similar observation was reported by Wang et al., (2009).

3.1 Acute effect of MPD (2.5mg/kg)-Recording at ED1

All 90 PFC units responded to 2.5mg/kg MPD i.p. by changing their firing rate: 66/90 (73%) units exhibited an increase of neuronal activity compared to baseline activity and 24/90 (27%) units exhibited a decrease of neuronal activity following the 2.5mg/kg MPD (Table 2A). Figure 1 illustrates two units recorded from two different animals following acute 2.5mg/kg MPD showing the above two response types of PFC units.

Table 2.

Summarizes the response to MPD 2.5 mg/kg i.p. administration. Table 2A shows how many units increase (↑) or decrease (↓) their firing rate after MPD administration, respectively. Table 2b summarizes the PFC units recorded at ED10 that at ED1 responded to MPD treatment by increasing firing rate. Table 2C summarizes the PFC units recorded at ED10 that at ED1 responded to MPD treatment by decreasing firing rate.

| A. Acute effect of MPD 2.5mg/kg | ||

|---|---|---|

| ED1 MPD 2.5mg/kg | ↑ | ↓ |

| N=90 | 66(73%) | 24(27%) |

Summary of how many units increased or decreased firing rate after acute MPD treatment.

Figure 1.

The figure shows representative firing rate of two PFC units. The upper unit exhibited increase in firing rate after acute 2.5 mg/kg MPD administration. The lower unit exhibited decrease in firing rate after acute 2.5mg/kg MPD. Arrow indicates the time of 2.5mg/kg MPD administration (Table 2A, N=90).

Figure 2 shows three different PFC units recorded from the same electrode exhibiting similar response direction to 2.5mg/kg MPD injection on ED1 by increasing their firing rate compared to ED1 baseline (Table 1). The recording illustrates that each unit responded to the MPD injection by an increase in activity but exhibited differences in latency and the duration of the drug effect (Figure 2). Unit A increased its firing rate at about 20 minutes post MPD injection and this increase in activity lasted about 64 minutes and then returned to baseline for the final recording. Figure 2 unit B exhibited an increase in firing rate following MPD injection after about 7 minutes (shorter latency period) post injection and the increase in firing rate lasted for approximately 50 minutes (shorter duration period) and then returned to baseline. Figure 2 unit C exhibited an increase in firing rate at about 5 minutes post MPD injection similar to unit B and this increase of firing rate post MPD injection lasted the 120 minute duration of the recording session.

Figure 2.

The figure represents three different units recorded simultaneously with the same electrode. The three PFC units exhibited similar response to acute 2.5mg/kg MPD administration i.e. increase of firing rate. The response latency and the duration of the MPD effect were different between these three units.

3.2 Chronic effect of MPD (2.5mg/kg)-Recording at ED10

Ninety (90) units exhibiting similar spikes pattern on ED1 and ED10 were analyzed for chronic MPD effect. These recordings were obtained before and after six consecutive daily 2.5mg/kg MPD administrations (ED1 to ED6), three washout days (ED7 to ED9) at ED10 (Table 1). On ED10, neuronal recordings were resumed from the same animals after saline and MPD (2.5mg/kg) injection similar to that obtained at ED1. The first comparison was comparing the baseline activity after saline injection of ED10 to ED1. Out of the 90 units, on ED1, 66 units (73%) exhibited increase firing rate. When these 66 units were rechallenged with MPD (2.5mg/kg) at ED10 they exhibited the following: 54/66 (82%) further increased their firing rate (P <0.05) at ED10 compared to ED1 baseline and 12/66 (18%) significantly (P <0.05) decreased their firing rate at ED10 compared to ED1 baseline (Table 2Ba). Figure 3 represents 2 PFC units that at ED10 exhibit the above two patterns i.e. increase in baseline (Figure 3A) and decrease in baseline (Figure 3B) at ED10 compared to ED1 baseline, respectively.

| B. Chronic effect of MPD at ED10 for units that increased at ED1 baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED10 Baseline | ↑ | ↓ | ||

| N=66a | 54(82%) | 12(18%) | ||

| ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| MPDb | 15(28%) | 39(72%) | 8(67%) | 4(33%) |

compares baseline of ED10 to baseline of ED1.

compares the effect of MPD at ED10 to baseline of ED10.

Figure 3.

The figure shows the baseline activity of two representative PFC units recorded in experimental day 1 (ED1) and at ED10 after six daily MPD administration (ED1 to ED6), three days of washout (ED7-ED9) and the baseline recorded at ED10. These two units at ED1 responded to 2.5mg/kg MPD administration by increasing the firing rate. The upper unit exhibited an increase in baseline activity at ED10 compared to ED1 baseline. The lower unit exhibited a decrease in baseline activity at ED10 compared to ED1 (see Table 2Ba).

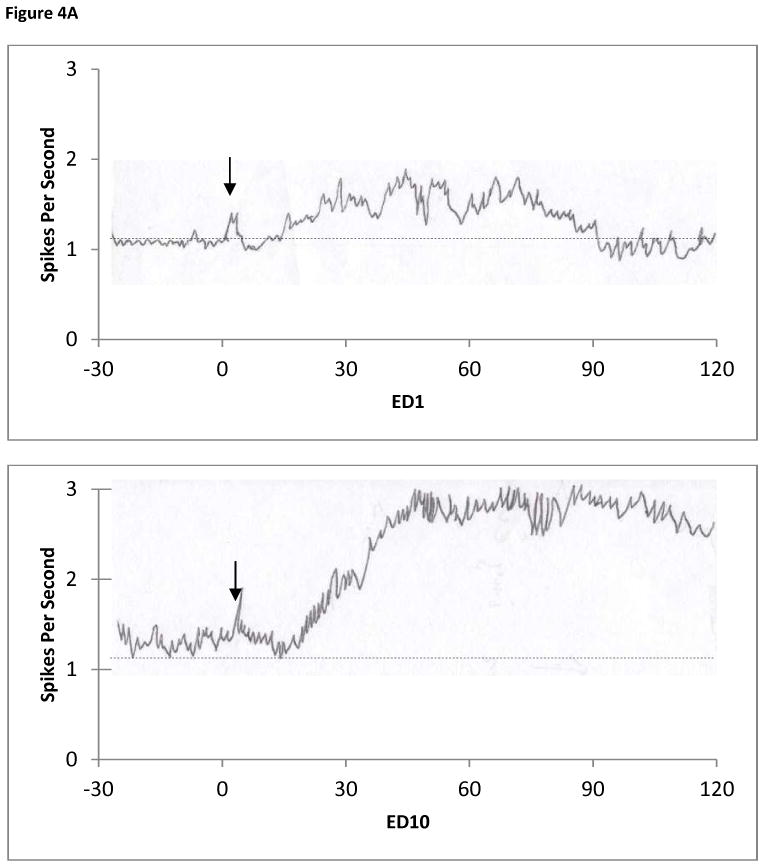

When those 54 PFC units that increased their baseline activity at ED10 compared to ED1 were rechallenged at ED10 with 2.5mg/kg MPD, 15/54 (28%) exhibited further increase in their firing rate and 39/56 (72%) exhibited a decrease in their firing rate (Table 2Bb). Figure 4A and B represents firing rates of 2 different PFC units recorded at ED1 (upper trace) and ED10 (lower trace) before and after MPD administration respectively aiming to show the activity at ED1 compared to ED10 following MPD injection. The units described in Figure 4A exhibit the following patterns i.e. small increase but significant (P <0.05) in firing rate at ED10 baseline and further, continued significant (P <0.05) increase following MPD injection (Figure 4A lower trace) at ED10. Figure 4B shows a representative unit that exhibits an increase in firing rate at ED10 baseline compared to ED1 and following MPD rechallenge the unit exhibits a decrease in firing rate following this injection on ED10 (Figure. 4B lower trace).

Figure 4.

The figure shows the baseline activity of two representative PFC units that exhibited increase activity following 2.5mg/kg MPD administration at ED1 and an increase in activity at ED10 baseline (Table 2Ba, N=54). Figure 4A upper trace shows the activity at ED1 i.e. MPD elicits increase firing rate. At ED10 the baseline increased and the effect of MPD elicited an increase in firing rate (Table 2Bb, N=15). Figure 4B upper trace shows the activity at ED1 i.e. MPD elicits an increase in firing rate. At ED10 (figure 4B lower trace) the baseline increased following the repetitive MPD administration and decreased following the MPD rechallenge (Table 2Bb, N=39).

Of the 12 units that exhibited a decrease in their baseline activity firing rate at ED10 compared to baseline at ED1 (Table 2B), 8/12 (67%) exhibited significant (P <0.05) increase in firing rate and 4/12 (33%) exhibited significant (P <0.05) decrease in firing rate after MPD rechallenge compared to ED10 baseline. Figure 5 shows the firing rates of 2 different PFC units recorded at ED10 compared to the activity recorded at ED1 for those units that exhibited decrease in baseline activity at ED10 i.e. further increase in firing rate post MPD injection at ED10 compared to ED1 (Figure 5A lower trace) and decrease in firing rate post MPD injection (Figure 5B lower trace).

Figure 5.

The figure shows two representative PFC units that exhibited increase activity following 2.5mg/kg MPD administration at ED1 and a decrease in activity at ED10 baseline (Table 2Ba, N=12). Figure 5A upper trace shows the activity at ED1 i.e. MPD elicits increase firing rate. At ED10 the baseline activity decreased and the effect of MPD elicited an increase in firing rate (Figure 5A lower trace, Table 2Bb, N=8). Figure 5B upper trace shows the activity at ED1 i.e. MPD elicits increase in firing rate. At ED10, lower trace, the baseline activity decreased following the repetitive MPD administration and the rechallenge of MPD elicited a further decrease in firing rate (Table 2Bb, N=4).

For the 24 units exhibiting a decrease of firing rate following 2.5mg/kg MPD at ED1 (Table 2A), the baseline activity at ED10 exhibited the following: 10/24 (42%) increased their baseline activity at ED10 compared to ED1 and 14/24 (58%) decreased their baseline activity at ED10 compared to ED1 (Table 2Ca). Figure 6 represents 2 PFC units that at ED10 exhibit the above two patterns i.e. increase in baseline (Figure 6A) and decrease in baseline (Figure 6B) at ED10 compared to ED1 baseline. When the 10 PFC units that exhibited increase in the baseline activity at ED10 (Table 2Ca) compared to ED1 were rechallenged at ED10 with 2.5mg/kg MPD, 1/10 (10.0%) exhibited increase in their firing rate and 9/10 (90%) exhibited further decrease in their firing rate (Table 2Cb). Of the 14 units that exhibited a decrease in their firing rate at ED10 baseline compared to ED1 baseline (Table 2Ca), 11/14 (79%) exhibited significant (P <0.05) increase in firing rate and 3/14 (21%) exhibited significant (P <0.05) decrease in firing rate following MPD (2.5mg/kg) rechallenge (Table 2Cb). Figure 7A shows a representative unit that exhibits decrease firing rate at ED1 following MPD administration and this unit at ED10 exhibits a decrease in baseline activity and following MPD administration significant increase in their activity. Figure 7B shows a representative unit of this group (Table 2C) that at ED1 exhibits a reduction in its neuronal activity following MPD administration, and at ED10 elicits further decrease in its neuronal activity.

| C. Chronic effect of MPD at ED10 for units that decreased at ED1 Baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED10 Baseline | ↑ | ↓ | ||

| N=24a | 10(42%) | 14(58%) | ||

| ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| MPDb | 1 (10%) | 9(90%) | 11(79%) | 3(21%) |

compares baseline of ED10 to baseline of ED1.

compares the effect of MPD at ED10 to baseline of ED10.

Figure 6.

The figure shows two representative baseline units (Table 2A and C, N= 24) recorded in experimental day 1 (ED1 and at ED10 after six daily MPD administration (ED1 to ED6), three days of washout (ED7-ED9) and the baseline recorded at ED10. These two units at ED1 responded to 2.5mg/kg MPD administration by decreasing their firing rate. The upper unit exhibited an increase in baseline activity at ED10 compared to ED1 baseline (Table 2Ca, N=10). The lower unit exhibited a decrease in baseline activity at ED10 compared to ED1 (Table 2Ca, N=14).

Figure 7.

Two representative units from the PFC that showed decrease activity following 2.5mg/kg MPD administration at ED1 (Table 2A and C, N=24) and further decrease in activity at ED10 baseline (Table 2Ca, N=14). Figure 7A upper trace shows the activity at ED1 i.e. MPD elicits decrease firing rate. At ED10 the baseline decreased and the effect of MPD elicited an increase in firing rate (Table 2Cb, N=11). Figure 7B upper trace shows the activity at ED1 i.e. MPD elicits decrease in firing rate. At ED10 the baseline activity decreased following the repetitive MPD administration and decreased following the rechallenge of MPD (Table 2Cb, N=3).

4 Discussion

Atypical development in the PFC can cause behavior disorders such as ADHD which result in neurobehavioral disorders such as ADHD. Indeed, children with ADHD appear to have a disrupted development of prefrontal asymmetry (Shaw et al., 2009) as well as catecholamine abnormalities in the PFC and caudate nucleus (CN) (Arnsten et al., 1996; Sergeant et al., 2002; Seidman et al., 2004; Bush et al., 2005). Studies on genetic anomalies in ADHD subjects have implicated dopaminergic genes as causative factors in this behavioral disorder (Cook et al., 1995). It was found that individuals with ADHD have at least one defective dopamine gene (Cook et al., 1995). New imaging studies of patients with ADHD indicate that the PFC is underactive and exhibits weakened connections to other parts of the brain (Arnsten, 2009). The PFC is highly dependent on the “neurochemical environment” and small changes in dopamine or noradrenaline will adversely affect PFC function (Arnsten, 2009).

The therapeutic effect of MPD has been attributed to its ability to bind to the dopamine transporter and block the reuptake of dopamine. This causes an increase in extracellular dopamine levels (Arnstem 2006; Challman and Lipsky 2000; Solanto 1998). Attempting to correct dopamine levels by using psycho stimulants for long periods of time ultimately leads to dependent patterns that result in systematically increasing drug use in order to achieve the initial effect. Since 1989, stimulant prescriptions have significantly increased, and MPD is being produced at 2.5 times the rate of a decade ago (Comings et al., 2005). Millions of children have taken Ritalin for years from a young age to adulthood (chronic effect) while college students may take the drug to help study for a test (acute effect) and before the exam to perform well. It is crucial, therefore, to investigate the effects of MPD on brains after one dose (acute) or multiple doses (chronic) of MPD administration. Thus, the objective of the present study was to investigate the acute and chronic effect of MPD on the PFC neurons in freely behaving rats previously implanted with permanent semi-microelectrodes (Dafny et al., 1983; Dafny and Terkel, 1990).

The main findings of this study are that all the PFC units responded to acute MPD (2.5mg/kg) administration, and the majority of them responded by accelerating their firing rates. Following rechallenge with MPD administration, after six daily MPD (2.5mg/kg) injections and three washout days the baseline of most of the PFC neurons was significantly altered, and the majority of them exhibit an increase in their baseline activity compared to MPD naïve animals at ED1, and some exhibit a decrease in their firing rate. Rechallenge with MPD at ED10 elicited eight different response patterns for the PFC units (Table 2Bb and 2Cb).

MPD is known to bind to the neuronal dopamine transporter (DAT) where it blocks the inward transport of dopamine into neuronal cells and thus increases extracellular dopamine levels as well as increase the recycling of the vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT-2). VMAT-2 is a protein that solely stores and transports cytoplasmic dopamine into synaptic vesicles inside neuronal cells (Leventhal, 1995, Voltz et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2005). MPD treatment in turn augments dopamine release in the postsynaptic cleft (Voltz et al., 2008). It has been found that a single injection of MPD redistributes VMAT-2 within nerve terminals away from the synaptosomal membranes and to the cytoplasm which results in an increase in dopamine levels (Voltz et al., 2008). D1 and D2 receptor activation is increased since MPD induces an increase in neurotransmitter speed and dopamine content (Voltz et al., 2008).

The PFC has pyramidal neurons with a high density of D1 like dopamine receptors and fewer D2 receptors, MPD administration results in increased dopamine activity in the PFC (Blum et al, 2008). It was reported that when dopamine binds to the D1 receptors it has an excitatory effect which can explain why the majority of the PFC neurons responded to acute MPD administration by excitation as our study shows. When dopamine binds to D2 receptors it has a suppression effect. Thus, those PFC neurons that exhibit D2 receptors following acute MPD administration exhibited attenuation in their firing rate activity. Consequently, this recording shows a strong correlation with how the PFC neurons responded to acute MPD administration i.e. direct correlation to the density of D1 and D2 receptors in the PFC.

Acute dose of MPD exerts a short term effect since it has minimal effects on VMAT2. However, the chronic (repeated) psychostimulant administration induced neuroadaptation that expressed alterations in molecular, cellular, soma and dendrite spine morphology i.e. structural plasticity of the neuropil (dense tangle of axon terminals, dendrites and glial cell processes) in the brain reward circuitry (Robinson and Kolb, 2004; Dietz et al., 2009; Russo et al., 2010). Some stimulants elicit increases in the neuropil while others cause decreases in the reward circuit neuropil (Russo et al., 2010). For example, repetitive doses of psychostimulants in rats increased dendrite length and branches in PFC neurons (Dietz et al., 2009). It was reported that the size and shape of the individual spine correlates with the form of synaptic plasticity and its electrophysiological expression (Bourne and Harris, 2007; Carlisle and Kennedy, 2005). In addition, psychostimulant administration elicits a transient increase in the brain derived nerve factor (BDNF) which induced plasticity (Bramham and Messaoudi, 2005) and elicits a dramatic increase in the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorilation (Sun et al., 2007). These in turn have been shown to alter dendrite branches and arborization as well as changes in the density and morphology of the dendritic spines and neurite complexity in the CNS reward nuclei such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens (NAc), and PFC and other areas (Lee et al., 2006; Robinson and Kolb 2004).

These molecular and morphological changes following repetitive MPD administration may explain why the majority of the PFC neurons altered their baseline activity at ED10 compared to ED1. This study shows that chronic MPD administration elicits several response patterns that can be attributed to the morphological plasticity and adaptation. Once the new baseline activity was established following the chronic MPD administration, as a result of increases in the receptors density at the soma in their neuropil, it may have also altered the number and density of dopamine receptors: either D1 or D2. In those neurons that the D1 receptors were increased can explain why MPD rechallenge elicited a further increase in neuronal activity which can also be interpreted as sensitization. In those neurons that the D2 receptors were increased the rechallenge of MPD administration elicited a further decrease in neuronal firing rate which can be interpreted as tolerance.

The majority of the PFC units exhibited an increase in their firing rates after MPD rechallenge. It is possible to postulate that this increase in activity is the outcome of the alteration in the cellular architecture and the amplification of the PFC neurons and its neuropil, as well as dopamine levels and VMAT2 following the repetitive psychostimulant administration (Pulipparacharuvil, 2008). In other words, the above “homeostatic adaptation” which occurred due to six repetitive MPD administration, three wash out days and rechallenge with MPD at ED10 caused a further increase in activity and longer lasting effects as compared to the recording from MPD naïve animals as our recording shows. However, some of our PFC units exhibit decreases in their firing rates after rechallenge with MPD at ED10. One possible postulation of this observation is based on the report that over stimulation of the neurons with repetitive drug administration sometimes caused decreases in the number of dopamine receptors and the remaining receptors become less sensitive to dopamine due to the repetitive effect of the drug. Thus, rechallenge with the drug elicits less effect or decrease in firing rate.

In conclusion, exposure to psychostimulant results in increase PFC soma and neuropil as well as in dopamine levels at the synaptic cleft and the subsequent activation of dopamine receptors. This activation leads to a cascade of intracellular events and structural plasticity. The D1 receptor family activation can directly or indirectly elicit an increase in firing rates while D2 like receptor family activation can lead to attenuation of the firing rate (Dietz et al., 2009). Moreover there is a strong link between an increase or decrease of the neuropil to behavioral sensitization and tolerance (Dietz et al., 2009). Indeed it is possible to postulate that those PFC units that exhibited further increase in the firing rate at ED10 following MPD rechallenge are the result of increases in the neuropil, D1 receptor density, or D1 receptor activation while those PFC units that exhibited decrease in firing rate following MPD rechallenge administration at ED10 are due to decrease in their neuropil, increase in the D2 receptor density, or increase in D2 receptor activation. It is important for future studies to analyze the transient properties of MPD. MPD like other psychostimulants initially elicits rewarding effects and later detrimental effects by increasing extracellular dopamine and VMAT2 concentrations which soon after alters the cells architecture. The question is whether chronic psychostimulant administration induced structural plasticity by modulation of the neuropil reflects in the PFC neurons response to chronic MPD treatment needs additional studies and more verification.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank A. Chelaru, S. Chong, B. Sonne for their technical help. This research was supported in part by NIH DA027222 grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Accardo P, Blondis TA. What’s all the fuss about Ritalin? J Pediatr. 2001;138:6–9. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algahim M, Yang P, Wilcox V, Burau K, Swann A, Dafny N. Prolong methylphenidate treatment alters the behavioral diurnal activity pattern of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats. Pharmacol Biochem And Behav. 2009;92:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Williams S, McGee R, Silva PA. DSM-III disorders in preadolescent children: prevalence in a large sample from the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:69–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800130081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio A. Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/14833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Steere JC, Hunt RD. The contribution of alpha 2-noradrenergic mechanisms of prefrontal cortical cognitive function. Potential significance for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:448–455. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050084013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Stimulants: Therapeutic actions in ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2376–2383. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Toward a new understanding of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder pathophysiology: an important role for prefrontal cortex dysfunction. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(Suppl 1):33–41. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins K, Burks T, Swann AC, Dafny N. MDMA (ecstasy) modulates locomotor and prefrontal cortex sensory evoked activity. Brain Res. 2009;1302:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresi W, Katusic S, Colligan R, Pankratz V, Weaver A, Weber KJ, Mrazek D, Jacobsen SJ. How common is attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Incidence in a population-based birth cohort in Rochester. Minn Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:217–224. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum K, Chen AL, Braverman ER, Comings DE, Chen TJ, Arcuri V, Blum SH, Downs BW, Waite RL, Notaro A, Lubar J, Williams L, Prihoda TJ, Palomo T, Oscar-Berman M. Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder and reward deficiency syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:893–918. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne J, Harris K. Do thin spines learn to be mushroom spines that remember? Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2007;17:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramham CR, Messaoudi E. BDNF function in adult synaptic plasticity: The synaptic consolidation hypothesis. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:99–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Valera EM, Seidman LJ. Functional neuroimaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review and suggested future directions. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1273–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Konradi C. Understanding the neurobiological consequences of early exposure to psychotropic drugs: linking behavior with molecules. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle H, Kennedy M. Spine architecture and synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challman TD, Lipsky JJ. Methylphenidate: its pharmacology and uses. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:711–721. doi: 10.4065/75.7.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Chen TJ, Blum K, Mengucci JF, Blum SH, Meshkin B. Neurogenetic interactions and aberrant behavioral co-morbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): dispelling myths. Theor Biol Med Model. 2005;2 doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-2-50. 1742-4682-2-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EH, Jr, Stein MA, Krasowski MD, Cox NJ, Olkon DM, Kieffer JE. Association of attention-deficit disorder and the dopamine transporter gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:993–998. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafny N, Phillips M, Taylor N, Gilman S. Dose effects of cortisol on single unit activity in hypothalamus, reticular formation, and hippocampus of freely behaving rats, correlated with plasma steroid levels. Brain Res. 1973;59:257–272. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafny N, Brown M, Burks T, Rigor B. Patterns of unit responses to incremental doses of morphine in central gray, reticular formation, medial thalamus, caudate nucleus, hypothalamus, septum and hippocampus in unanesthetized rats. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1979;3:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(79)90075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafny N. Neurophysiological evidence for tolerance and dependence on opiates: Simultaneous multiunit recordings from septum, thalamus and caudate nucleus. J Neurosci Res. 1980;5:339–349. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490050410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafny N, Marchand J, McClung R, Salamy J, Sands S, Wachtendorf H, Burks T. Effects of morphine on sensory evoked responses recorded from central gray, reticles formation, thalamus, hypothalamus, limbic system, basal ganglia, dorsal raphe, locus ceruleus, and pineal body. J Neurosci Res. 1981;5:399–412. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490050505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafny N, Burks T, Bergman F. Dose effects of morphine on the spontaneous unit activity recorded from thalamus, hypothalamus, septum, hippocampus, reticular formation, central gray and caudate nucleus. J Neurosci Res. 1983;9:115–126. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490090203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafny N, Terkel J. Hypothalamic neuronal activity associated with onset of pseudopregnancy in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1990;51:459–467. doi: 10.1159/000125375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sola S, Tarancón T, Peña-Casanova J, Espadaler J, Langohr K, Poudevida S, Farré M, Verdejo-garcia A, d la Torré R. Auditory event-related potentials (P3) and cognitive performance in recreational ecstasy polydrug users: evidence from a 12-month longitudinal study. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:425–437. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz DM, Dietz KC, Nestler EJ, Russo SJ. Molecular mechanisms of psychostimulant-induced structural plasticity. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42:S69–78. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichlseder W. Ten years of experience with 1.000 hyperactive children in a private practice. Pediatr. 1985;76:176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich T, Lanphear B, Epstein J, Barbaresi W, Katusic S, Kahn RS. Prevalence, recognition, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a national sample of US children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:857–864. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.9.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi S, Bruce G, Goldman-Rakic P. Mnemonic coding of visual space in the monkey’s dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:331–349. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatley S, Volkow N, Gifford A, Fowler J, Dewey S, Ding Y, Logan J. Dopamine-transporter occupancy after intravenous doses of cocaine and methylphenidate in mice and humans. Psychopharmacol. 1999;146:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s002130051093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaytan O, Ghelani D, Martin S, Swann A, Dafny N. Dose response characteristics of methylphenidate on different indices of rats’ locomotor activity at the beginning of the dark cycle. Brain Res. 1996;727:13–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaytan O, Al-Rahim S, Swann A, Dafny N. Sensitization to locomotor effects of methylphenidate in the rat. Life Sci. 1997;61:PL101–PL107. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00598-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaytan O, Yang P, Swann A, Dafny N. Diurnal differences in sensitization to methylphenidate. Brain Res. 2000;864:24–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic P. Circuitry of the primate prefrontal cortex and the regulation of behavior by representational memory. In: Plum F, editor. Handbook of Physiology. The Nervous System. Higher Functions of the Brain. Part 1 Vol. 5. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, M.D: 1987. pp. 373–417. Section 1. [Google Scholar]

- Greely H, et al. Towards responsible use of cognitive-enhancing drugs by the healthy. Nature. 2008;456:702–705. doi: 10.1038/456702a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallman WM, Isaac W. The effects of age and illumination on the dose-response curve for three stimulants. Psychopharmacologia (Berl) 1975;40:313–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00421469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins S, MacDonald E, Rush C. Assessing the abuse potential of methylphenidate in nonhumans and human subjects. A review Pharm Biochem Behav. 2001;68:611–627. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00464-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal D. Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2032–2037. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Kim Y, Kim A, et al. Cocaine-induced dendritic spine formation in D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-containing medium spiny neurons in nucleas accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;77:2794–2803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511244103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Yang P, Wilcox V, Burau K, Swann A, Dafny N. Does repetitive Ritalin injection produce long-term effects on SD female adolescent rats? Neuropharmacol. 2009;57:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal BL. Association of attention-deficit disorder and the dopamine transporter gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:993–998. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser C, Ahmann P, Theye F, Mundt P, Broste S, Mueller-Rizner N. Stimulant use and the potential for abuse in Wisconsin as reported by school administrators and longitudinally followed children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19:187–192. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199806000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrics KS, Markowitz JS. Pharmacology of methylphenidate, amphetamine enantiomers, and penoline in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders. Human Psychopharmacol. 1997;12:527–546. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinate. 2. Academic Press; Orlando: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Podet A, Lee M, Swann A, Dafny N. Nucleus accumbens lesions modulate the effects of methylphenidate. Brain Res Bull. 2010;82:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulipparacharuvil S, Renthal W, Hale C, et al. Cocaine regulates MEF2 to control synaptic and behavioral plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:621–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T, Kolb B. Structural plasticity associated with exposure to drugs of abuse. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland A, Umbach D, Catoe K, Stallone L, Long S, Rabiner D, Naftel AJ, Panke D, Faulk R, Sandler DP. Studying the epidemiology of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: screening method and pilot results. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46:931–940. doi: 10.1177/070674370104601005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Dietz DM, Dumitriu D, Morrison JH, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. The addicted synapse: mechanisms of synaptic and structural plasticity in nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweri M, Deutsch H, Massey A, Holtzman SG. Biochemical and behavioral characterization of novel methylphenidate analogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:527–535. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman L, Valera E, Bush G. Brain function and structure in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27:323–347. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal D, Kuczenski R. Repeated binge exposure to amphetamine and methamphetamine: Behavioral and neurochemical characterization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:561–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant JA, Geurts H, Oosterlaan J. How specific is a deficit of executive functioning for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Behav Brain Res. 2002;130:3–28. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Lalonde F, Lepage C, Rabin C, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, Greenstein D, Evans A, Giedd JN, Rapoport J. Development of cortical asymmetry in typically developing children and its disruption in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:888–896. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanto MV. Neuropsychopharmacological mechanisms of stimulant drug action in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a review and integration. Behav Brain Res. 1998;94:127–152. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J, Gupta S, Guinta D, Flynn D, Agler D, Lerner M, Williams L, Shoulson I, Wigal S. Acute tolerance to methylphenidate in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66:295–305. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70038-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Zhou L, Hazim R, et al. Effects of acute cocaine on ERK and DARPP-32 phosphorylation pathways in the caudate-putamen of fischer rats. Brain Research. 2007;1178:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo SK, Stirling DI, Thomas SD, Khetani V. Neurobehavioral effects of racemic threomethlphenidate and its D and L enantiomers in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74:747–754. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Logan J, Gatley JS, Dewey S, Ashby C, Liebermann J, Hitzemann R. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:456–463. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950180042006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N, Wang G, Fowler J, Fischman M, Foltin R, Abumrad N, Gatley S, Logan J, Wong C, Gifford A, Ding Y, Hitzemann R, Pappas N. Methylphenidate and cocaine have a similar in vivo potency to block dopamine transporters in the human brain. Life Sci. 1999;65:PL7–PL12. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz TJ, Farnsworth SJ, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Methylphenidate-induced alterations in synaptic vesicle trafficking and activity. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1139:285–290. doi: 10.1196/annals.1432.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zhang Q, Liu J, Wu Z, Ali U, Wang Y, Chen L, Gui Z. The firing activity of pyramidal neurons in medial prefrontal cortex and their response to 5-hydroxytryptamine-1A receptor stimulation in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2009;162:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J, Grafman J. Human prefrontal cortex: processing and representational perspectives. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:139–147. doi: 10.1038/nrn1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Beasley A, Swann A, Dafny N. NMDA receptor antagonist disrupt acute and chronic effects of methylphenidate. Physiol And Behav. 2000a;71:133–145. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Beasley A, Swann A, Dafny N. Valproate modulates the expression of methylphenidate (Ritalin) sensitization. Brain Res. 2000b;874:216–220. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Swann A, Dafny N. Chronic pretreatment with methylphenidate induces cross-sensitization with amphetamine. Life Sci. 2003;73:2899–2911. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Swann A, Dafny N. Acute and chronic methylphenidate dose response assessment on three adolescent male rat strains. Brain Res Bull. 2006a;71:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Swann A, Dafny N. Dose-response characteristics of methylphenidate on locomotor behavior and on sensory evoked potentials recorded from the VTA, NAc, and PFC in freely behaving rats. Behav Brain Funct. 2006b;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Swann A, Dafny N. Sensory-evoked potentials recordings from the ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex, and caudate nucleus and locomotor activity are modulated in dose-response characteristics by methylphenidate. Brain Res. 2006c;1073–1074:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Swann A, Dafny N. Acute and chronic methylphenidate dose-response assessment on three different male rat strains. Brain Res Bull. 2006d;71:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Swann A, Dafny N. Chronic administration of methylphenidate produces neurophysiological and behavioral sensitization. Brain Res. 2007;1145:66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Swann A, Dafny N. Psychostimulant given to adolescence modulate their effects in adulthood using the open field and the wheel running assays. Brain Res Bull. 2010;82:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Dwoskin L, Deaciuc A, Norrholm S, Crooks P. Defunctionalized lobeline analogues: structure-activity of novel ligands for the vesicular monoamine transporter. J Med Chem. 2005;13:3899–3909. doi: 10.1021/jm0501228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]