Abstract

Near-IR (NIR) imaging is a new technology that is currently being investigated for the detection and assessment of dental caries without the use of ionizing radiation. Several papers have been published on the use of transillumination and reflectance NIR imaging to detect early caries in enamel. The purpose of this study was to investigate alternative near infrared wavelengths besides 1300-nm in the range from 1200–1600-nm to determine the wavelengths that yield the highest contrast in both transmission and reflectance imaging modes. Artificial lesions were created on thirty tooth sections of varying thickness for transillumination imaging. NIR images at wavelengths from the visible to 1600-nm were also acquired for fifty-four whole teeth with occlusal lesions using a tungsten halogen lamp with several spectral filters and a Ge-enhanced CMOS image sensor. Cavity preparations were also cut into whole teeth and Z250 composite was used as a restorative material to determine the contrast between composite and enamel at NIR wavelengths. Slightly longer NIR wavelengths are likely to have better performance for the transillumination of occlusal caries lesions while 1300-nm appears best for the transillumination of proximal surfaces. Significantly higher performance was attained at wavelengths that have higher water absorption, namely 1460-nm and wavelengths greater than 1500-nm and these wavelength regions are likely to be more effective for reflectance imaging. Wavelengths with higher water absorption also provided higher contrast of composite restorations.

Keywords: Near-IR imaging, occlusal surfaces, dental caries, transillumination

1. INTRODUCTION

Enamel is virtually transparent in the NIR with optical attenuation 1–2 orders of magnitude less than in the visible range 1, 2. Several studies have been carried out by our group over the past seven years and have demonstrated that interproximal caries lesions can be imaged by transillumination of the proximal contact points between teeth and by directing NIR light below the crown while imaging the occlusal surface both in vitro and in vivo 3–5. The same approach can be used to image occlusal lesions with high contrast 5–10. Early enamel white spot lesions can be discriminated from sound enamel by visual observation or by visible-light diffuse reflectance imaging 11, 12. The visibility of scattering structures on highly reflective surfaces such as teeth can be enhanced by use of crossed polarizers to remove the glare from the surface due to the strong specular reflection from the enamel surface 13, 14. The contrast between sound and demineralized enamel can be further enhanced by depolarization of the scattered light in the area of demineralized enamel 8, 15. Recently we have demonstrated that we can acquire high contrast reflectance images of buccal and occlusal surfaces and that the contrast at 1300-nm exceeded visible light reflectance and blue-green or quantitative light (QLF) fluorescence 16. The contrast between sound and demineralized enamel is greatest in the NIR due to the minimal scattering of sound enamel and this can be exploited for reflectance imaging of early demineralization 17. Wu et al. 16 reported the first high contrast polarized reflectance images of early demineralization on buccal and occlusal tooth surfaces measured at λ=1310-nm and found that the contrast was significantly higher at 1310-nm than in the visible range. Zakian 18 carried out NIR reflectance measurements from 1000–2500-nm using a hyperspectral imaging system and showed that the reflectance from sound tooth areas decreases at longer wavelengths in the NIR where water absorption is higher.

Two distinct advantages were noted in our previous NIR imaging studies over visible light methods. In NIR images of the occlusal surfaces, stains were often not visible since the organic molecules responsible for pigmentation absorb poorly in the NIR 7 making it easier to identify areas of demineralization. Mild developmental defects9 and shallow demineralization 16 appeared differently from deeper and more severe demineralization due to caries suggesting that we may be able to gauge the severity of lesions by analyzing both NIR reflective images and NIR transillumination images of these surfaces.

The purpose of this imaging study was to determine which NIR wavelengths between 1200 and 1600-nm provide the highest contrast of demineralization or caries lesions for each of the different modes of NIR imaging including transillumination of proximal and occlusal surfaces along with cross polarization reflectance measurements.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Sample preparation

Extracted teeth from patients in the San Francisco bay area were collected with approval from the UCSF Committee on Human Research, cleaned, sterilized with gamma radiation, and stored in a 0.1% thymol solution to preserve tissue hydration and prevent bacterial growth. Teeth with apparent occlusal lesions (n=54) were selected for imaging and mounted in orthodontic resin blocks with the cementoenamel junctions exposed. Radiographs and visible light images were acquired of each tooth. In addition, thirty sound human teeth were selected and sections of varying thickness from 2–6-mm thick were cut using a linear precision saw, the IsoMet 2000 (Buehler, Lake Buff, IL). A small incision with a small diameter (800-µm) bur was cut into the enamel in the center of each tooth section slightly past the dentin-enamel junction and the hole was filled with hydroxyapatite powder to simulate caries lesions as was done in a similar fashion to prior studies3, 4. A layer of bonding resin was applied to the outside of the incision to prevent the hydroxyapatite from falling out. Cavity preparations were cut into a whole tooth and Z250 composite was used as a restorative material to determine the contrast between composite and enamel at NIR wavelengths.

2.2 Near infrared (NIR) imaging

A NoblePeak Vision Triwave Imager, Model EC701 (Wakefield, MA) was used that employs a Germanium enhanced complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) focal plane array sensitive from 400–1600-nm with a larger array (640×480) and smaller pixel pitch (10-µm pixels) for higher resolution. Light from a 150-W fiber-optic illuminator FOI-1 E Licht Company (Denver, CO) coupled to an adjustable aperture and several band-pass (BP) and long-pass (LP) filters were used to provide different spectral distributions of NIR and visible light. Visible light was provided using a short pass filter, FSR-KG5 from Newport (Irvine, CA) with a cutoff of 800-nm. Long-pass filters at 1200, 1300, 1400 and 1500-nm and band-pass filters with a 40–50-nm bandwidth centered at 1300, 1460 and 1550-nm were used for NIR light. Three imaging configurations were used as shown in Fig. 1. Images of natural lesions on the occlusal surfaces of whole teeth were acquired using the first setup shown in Fig 1. Selected NIR wavelengths are delivered by a low profile fiber optic with dual line lights, Model P39–987 (Edmund Scientific, Barrington, NJ) with each light line directed at the cementoenamel junction beneath the crown on the buccal and lingual sides of each tooth. Light leaving the occlusal surface is directed by a right angle prism to the Triwave imager with an Infinimite™ video lens (Infinity, Boulder, CO). The second setup shown in Fig.1 was used for the transillumination of the enamel sections of varying thickness. The third setup of Fig. 1 was used for reflectance measurements of natural occlusal caries lesions. Light was directed towards the occlusal surface through a broadband UV fused silica beamsplitter (1200–1600-nm) Model BSW12 (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) and the reflected NIR light from the tooth was transmitted by the beamsplitter to the Triwave imager. Crossed polarizers were used to remove specular reflection (glare) that interferes with measurements of the lesion contrast.

Fig. 1.

NIR imaging setups for (1) occlusal transillumination imaging, (2) transillumination of sections with simulated lesions, and (3) occlusal reflectance imaging (A) light, (B) prism or beamsplitter and (C) Ge-CMOS imager.

One problem with the Triwave imager was that the gain of certain groups of pixels on the focal plane array varied with wavelength so that either white spots or dark spots were visible when using different filters. These were not dead pixels, they are pixels that have a different spectral responsivity. We applied two methods for correction. Images without the samples collected in transillumination or reflection using a white reference target were collected to use for non-uniformity correction of both the response of the FPA and the uniformity of the light source. This was not possible for the occlusal transillumination measurements and a simple box filter was applied to the image over a range of 5 pixels to remove the small dots from the image. Note that contrast calculations were carried out before any filtering.

2.3 Histology and Image analysis

Line profiles were extracted from each image aligned with the histological sections and lesion or image contrast was calculated using (IL – IS)/IL; where IS is the mean intensity of the sound enamel, and IL is the mean intensity of the lesion area. The image contrast varies from 0 to 1 with 1 being very high contrast and 0 being no contrast. All image analysis was carried out using Igor Pro software from Wavemetrics (Lake Oswego, OR). A one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey-Kramer post hoc multiple comparison test was used to compare groups for each type of lesion employing InStat software from GraphPad (San Diego, CA).

3. RESULTS

Figure 2 shows transillumination images through one of the 5-mm thick sections with an artificial lesion taken at visible wavelengths (KG5 glass filter) and in the NIR with three NIR bandpass filters taken using the setup of Fig. 1(#2). The lesion cannot be seen at all in the visible, (Fig. 2A). The lesion appears with high contrast for all three of the NIR wavelengths. The contrast was slightly higher for the 1300-nm LP and BP filters and lower for the 1400-nm LP and 1460-nm BP filters.

Fig. 2.

Transillumination images trough a 5-mm thick tooth section from Triwave Ge-CMOS imager with (A) KG5 glass filter 300–800-nm, and (B) 1300-nm and (C) 1460-nm (D) 1550-nm BP filters. The lesion is located in the yellow box.

NIR occlusal transillumination images taken using three LP filters at 1300, 1400, and 1500-nm are shown in Figure 3, taken using the setup of Fig. 1(#1). The highest contrast was for the 1400-nm LP filter which was slightly higher than the 1300-nm LP filter. The contrast for the 1500-nm LP filter is very low and the lesion cannot be discriminated from the very dark area of the dentin.

Fig. 3.

NIR transillumination measurements show significantly higher contrast for the LP 1400-nm filter. Note the poor contrast at longer wavelengths with higher water absorption, namely LP 1500-nm.

Reflectance images of a tooth with occlusal decay are shown in Fig. 4 for three filters taken using the setup of Fig. 1(#3). In the visible, (Fig. 4A), the contrast is due to stains in the fissures and areas of demineralization are not obvious. An extended area of demineralization is visible at 1300-nm and the area of demineralization appears whiter as it should since demineralization increases the light scattering reflectivity from the lesion area. The highest contrast is achieved for the 1460-nm BP filter and the reflectivity from the sound enamel areas is minimal.

Fig. 4.

Reflectance images from Triwave Ge-CMOS imager with (A) KG5 glass filter 300–800-nm, and (B) 1300-nm and (C) 1460-nm BP filters.

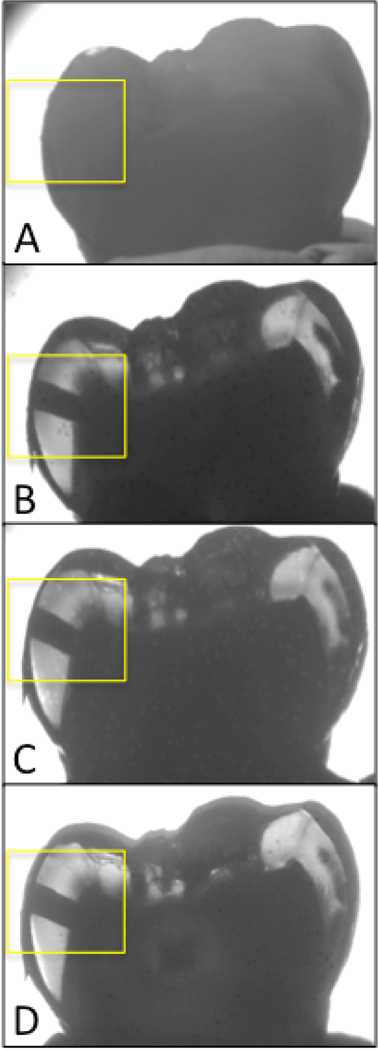

Figure 5 shows NIR occlusal transillumination images and a visible light reflectance image of a tooth with a composite restoration. The contrast is quite low between the composite and surrounding tooth structure for both the reflectance and transillumination visible light image. The composite can be seen with higher contrast in the transillumination image taken at 1300-nm, the composite restoration appears lighter. The contrast is much higher at 1460-nm where the composite is much lighter than the surrounding enamel.

Fig. 5.

Images of a tooth with a composite restoration (Z-250, 3M) in the area of the white box. Transillumination images are shown in for (A) 1460-nm, (B)1300-nm, and (C) visible wavelengths while a visible light reflectance image is shown in D.

4. DISCUSSION

This study exploring other NIR wavelengths beyond 1300-nm suggests that other NIR wavelengths are likely to provide higher contrast for certain imaging modes. For conventional transillumination of interproximal lesions 1300-nm provided the highest contrast. It appeared that increasing water absorption decreased the contrast for transillumination of proximal surfaces. There was improved contrast using a 1400-nm long-pass filter versus both the 1300-nm band-pass and 1300-nm long pass filters for imaging occlusal lesions using the approach in which the NIR light is delivered beneath the crown and the lesions are viewed from the occlusal surfaces (transillumination mode). This was a surprise and additional studies are needed to determine the mechanism of increased contrast. One possible explanation could be a marked decrease in the scattering of dentin and we plan on measuring the optical scattering in dentin at longer wavelengths. Hyperspectral reflectance measurements of Zakian 18 show that the dentin gets darker with increasing wavelength even when water absorption is not increasing which suggests that the dentin scattering coefficient decreases at longer NIR wavelengths. Wavelengths where water absorption increased performed poorly due to the high water content in dentin as can be seen in Fig. 3. The underlying dentin appears very dark due to water absorption so that there is minimal contrast between the occlusal lesions and the surrounding dentin. The performance of reflectance measurements at wavelengths such as 1460-nm where water absorption increases was significantly higher than at 1300-nm and this wavelength looks very promising for NIR reflectance measurements. The contrast is highest at these wavelengths because the higher water content reduces backscattered light from the underlying dentin which reduces contrast in reflectance images.

Zakian et al. 18 combined the reflectance values from multiple NIR wavelengths 1090, 1440 and 1610-nm as an indicator of caries severity. It would be challenging to use such an approach for clinical imaging. Our previous reflectance measurements carried out on 47 teeth at 1300-nm failed to show a marked increase in contrast with lesion depth in reflectance10, while two studies showed that the contrast increased significantly with lesion depth in occlusal transillumination measurements at 1300-nm6, 10. It is difficult to use reflectance measurements alone to estimate the depth of the caries lesions because the scattering coefficient of dental enamel increases 2–3 orders of magnitude upon demineralization (µs=100–200 cm−1) 17. Therefore the mean free path of NIR photons in lesions is only 50-µm, and the amount of light reflected from the lesion area should not increase appreciably for lesions that are greater in depth than 500-µm 19, and it should not be feasible to estimate the depth or severity of deeper occlusal lesions from reflectance images unless sound enamel is above the lesion.

NIR reflectance images are best suited for assessing early demineralization on the occlusal surfaces and we postulate they are superior to visible reflectance images because of the markedly higher lesion contrast and the lack of interference from stain, while the occlusal transillumination images are best suited for estimating the lesion depth. Shallow lesions should be visible with high contrast in reflectance while they should either not be visible or be visible with low contrast in occlusal transillumination images. Conversely lesions hidden under the sound enamel are likely to be visible on the occlusal transillumination image while they may not be visible or be visible with low contrast in the reflectance image since the lesion is not located near the surface. In our prior occlusal caries NIR imaging study, we investigated using the ratio of contrast in reflectance and transilumination to assess the lesion depth, however demineralization was only localized to the surface for a few of the teeth so the contribution from reflectance was minimal, i.e., almost all the lesions were visible in the occlusal transillumination images10.

A thorough statistical analysis of the measurements on all of the samples will be submitted for publication in a future paper. In summary, it appears that slightly longer NIR wavelengths are likely to have better performance for the transillumination of occlusal caries lesions while 1300-nm appears best for the transillumination of proximal surfaces. Significantly higher performance was attained at wavelengths that have higher water absorption, namely 1460-nm and greater than 1500-nm and these wavelength regions are likely to be more effective for reflectance imaging. Wavelengths with increased water absorption are also likely to be more effective for imaging around composite restorations due to the lower water content of composite as can be seen in Fig. 5.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the support of NIH grant R01-DE14698.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fried D, Featherstone JDB, Glena RE, Seka W. The nature of light scattering in dental enamel and dentin at visible and near-IR wavelengths. Appl. Optics. 1995;34(7):1278–1285. doi: 10.1364/AO.34.001278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones RS, Fried D. Attenuation of 1310-nm and 1550-nm Laser Light through Sound Dental Enamel. Lasers in Dentistry VIII. 2002;Vol. 4610:187–190. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones G, Jones RS, Fried D. Transillumination of interproximal caries lesions with 830-nm light. Lasers in Dentistry X. 2004;Vol. 5313:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RS, Huynh GD, Jones GC, Fried D. Near-IR Transillumination at 1310-nm for the Imaging of Early Dental Caries. Optics Express. 2003;11(18):2259–2265. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.002259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staninec M, Lee C, Darling C, Fried D. In vivo near-IR imaging of approximal dental decay at 1310 nm. Lasers in Surg. Med. 2010;42(4):292–298. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee C, Darling CL, Fried D. In vitro near-infrared imaging of occlusal dental caries using a germanium enhanced CMOS camera. Lasers in Dentistry XVI. 2010;Vol. 7549 doi: 10.1117/12.849338. pp. 75490K:75491-75497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bühler CM, Ngaotheppitak P, Fried D. Imaging of occlusal dental caries (decay) with near-IR light at 1310-nm. Optics Express. 2005;13(2):573–582. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.000573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried D, Featherstone JDB, Darling CL, Jones RS, Ngaotheppitak P, Buehler CM. Early Caries Imaging and Monitoring with Near-IR Light. Philadelphia: W. B Saunders Company; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirasuna K, Fried D, Darling CL. Near-IR imaging of developmental defects in dental enamel. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008;13(4) doi: 10.1117/1.2956374. 044011:044011-044017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee D, Fried D, Darling C. Near-IR multi-modal imaging of natural occlusal lesions. Lasers in Dentistry XV. 2009;Vol. 71620:X1–X7. doi: 10.1117/12.816866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angmar-Mansson B, ten Bosch JJ. Optical methods for the detection and quantification of caries. Adv. Dent. Res. 1987;1(1):14–20. doi: 10.1177/08959374870010010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ten Bosch JJ, van der Mei HC, Borsboom PCF. Optical monitor of in vitro caries. Caries Res. 1984;18:540–547. doi: 10.1159/000260818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson PE, Ali Shah A, Robert Willmot D. Polarized versus nonpolarized digital images for the measurement of demineralization surrounding orthodontic brackets. Angle Orthod. 2008;78(2):288–293. doi: 10.2319/121306-511.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everett MJ, Colston BW, Sathyam US, Silva LBD, Fried D, Featherstone JDB. Non-invasive diagnosis of early caries with polarization sensitive optical coherence tomography (PS-OCT) Lasers in Dentistry V. 1999;Vol. 3593:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried D, Xie J, Shafi S, Featherstone JDB, Breunig T, Lee CQ. Early detection of dental caries and lesion progression with polarization sensitive optical coherence tomography. J. Biomed. Optics. 2002;7(4):618–627. doi: 10.1117/1.1509752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JI, Fried D. High Contrast Near-infrared Polarized Reflectance Images of Demineralization on Tooth Buccal and Occlusal Surfaces at λ=1310-nm. Lasers in Surg. Med. 2009;41:208–213. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darling CL, Huynh GD, Fried D. Light Scattering Properties of Natural and Artificially Demineralized Dental Enamel at 1310-nm. J. Biomed. Optics. 2006;11(3) doi: 10.1117/1.2204603. 034023 034021-034011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zakian C, Pretty I, Ellwood R. Near-infrared hyperspectral imaging of teeth for dental caries detection. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2009;14(6) doi: 10.1117/1.3275480. 064047:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuchin V. Tissue Optics: Light Scattering Methods and Instruments for Medical Diagnostics. Bellingham: SPIE; 2000. [Google Scholar]