Background: In cell-matrix adhesions, vinculin is activated by talin and actin, but the identity of the ligand that activates vinculin in cell-cell adhesions is unknown.

Results:α-Catenin activates vinculin and the A50I talin-binding mutant of vinculin.

Conclusion: These data suggest that α-catenin employs a novel mechanism to activate vinculin.

Significance: These findings explain how vinculin is differentially activated in cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions.

Keywords: Adherens Junction, Adhesion, Cadherins, Cell Junctions, Signal Transduction, α-Catenin, Vinculin

Abstract

Vinculin, an actin-binding protein, is emerging as an important regulator of adherens junctions. In focal-adhesions, vinculin is activated by simultaneous binding of talin to its head domain and actin filaments to its tail domain. Talin is not present in adherens junctions. Consequently, the identity of the ligand that activates vinculin in cell-cell junctions is not known. Here we show that in the presence of F-actin, α-catenin, a cytoplasmic component of the cadherin adhesion complex, activates vinculin. Direct binding of α-catenin to vinculin is critical for this event because a point mutant (α-catenin L344P) lacking high affinity binding does not activate vinculin. Furthermore, unlike all known vinculin activators, α-catenin binds to and activates vinculin independently of an A50I substitution in the vinculin head, a mutation that inhibits vinculin binding to talin and IpaA. Collectively, these data suggest that α-catenin employs a novel mechanism to activate vinculin and may explain how vinculin is differentially recruited and/or activated in cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions.

Introduction

Cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion is required for the formation of tissue boundaries and the separation of tissue layers that occurs during embryogenesis (1–4). In adult tissues, cell-cell adhesions are spatially and temporally regulated to allow for the passage of lymphoid cells across cell layers (4–6). Developmental and cellular cues alter cell-cell adhesion by facilitating the assembly and disassembly of protein complexes at the cadherins cytoplasmic tail (7), but the molecular events that regulate these processes remain poorly understood.

Vinculin is recruited to the cadherin adhesion complex by binding to β-catenin, and it governs cadherin function. For example, our laboratory showed that vinculin is required for stabilizing E-cadherin on the cell surface and that in its absence, cell-cell junctions do not properly assemble (8). Similarly, conditional knock-out of vinculin in the cardiomyocytes of mice resulted in disrupted N-cadherin-mediated cell-cell junctions and depolarized localization of gap junctions (9). Others demonstrated that vinculin acts downstream of myosin VI to regulate the maturation of cell-cell adhesions (10). In addition to regulating the assembly and maintenance of junctions, vinculin is critical for E-cadherin-mediated mechanosensing (11). These studies establish vinculin as a critical component of the cadherin adhesion complex, but how vinculin is regulated at this site is not known.

Vinculin has no enzymatic activity; rather it functions by binding to other proteins. For example, efficient membrane protrusion requires transient recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin in adhesions in the leading edge of spreading cells (12), whereas the extent of integrin clustering requires vinculin binding to both talin and actin (13). In order for vinculin to bind ligands, an inactivating intramolecular interaction between its head and tail domains must be relieved (14–16). The relaxation of this intramolecular interaction has been termed vinculin activation. In cell-matrix or focal adhesions, the mechanism for vinculin activation is somewhat controversial with some groups proposing that a single ligand, talin, activates vinculin and others demonstrating a requirement for talin and actin filaments (17–22). Talin is not present in adherens junctions. Therefore, another ligand must activate vinculin in this region of the cell. In this study, we tested whether α- or β-catenin, two cadherin adhesion complex components that bind vinculin, can activate it (23, 24). We found that α-catenin, but not β-catenin, activates vinculin, and that this activation requires binding of vinculin to actin filaments. We generated an α-catenin point mutant that does not bind vinculin and found that vinculin activation requires direct binding to α-catenin. Furthermore, we report that α-catenin, unlike all the other known vinculin activators, binds and activates vinculin in the presence of an A50I substitution in the vinculin head. These data suggest that α-catenin employs a distinct and novel mechanism to activate vinculin. In addition, the results provide new evidence for stable activation of vinculin by coincident action of two ligands.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Constructs

pEGFP-V1–1066± A50I, pEGFP-V1–851± A50I are previously described (16). The vinculin FRET probe TP3 was constructed to be identical to TP2 (20) except that EYFP was replaced with monomeric citrine and ECFP was replaced with monomeric cerulean. The A50I mutation was introduced into TP3 using site-specific mutagenesis. pGEX4T1-FL α-catenin is a full-length human α-catenin cDNA fused in-frame with GST, and was a generous gift from David Rimm (Yale University). pET21-rTev-α-catenin 273–510, pET21-rTev-β-catenin 1–131 or pGEX4T1-α-catenin truncations (Fig. 2) were constructed by PCR amplifying corresponding residues of human α-catenin or mouse β-catenin and subcloning this into pET21-rTev (a generous gift of Ernesto Fuentes, University of Iowa) or pGEX4T1 (GE Healthcare). pET21-rTev-α-catenin 273–510 L344P, pGEX4T1-α-catenin 273–510 L344P, and pGEX4T1-FL α-catenin L344P were prepared by using site-specific mutagenesis to introduce a mutation resulting in the appropriate single amino acid substitution into pET21-rTev-α-catenin 273–510, pGEX4T1-α-catenin 273–510, and pGEX4T1-FL α-catenin.

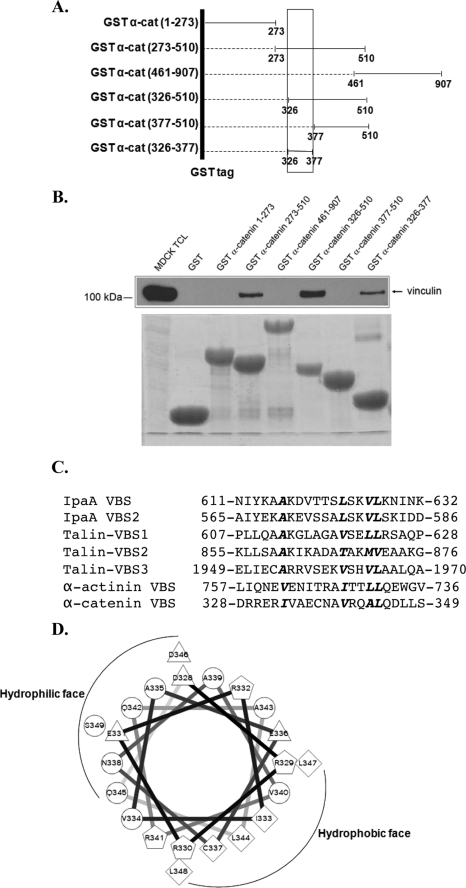

FIGURE 2.

Mapping the vinculin binding site of α-catenin. A, schematic of α-catenin (α-cat) fragments fused to GST that were employed in this study. The amino acids of each α-catenin fragment are indicated in the parentheses. The box indicates the vinculin binding site on α-catenin. The dotted line indicates the region of α-catenin that has been deleted. B, an analysis of the vinculin binding site on α-catenin. Equal amounts of purified GST or GST-tagged α-catenin fragments attached to the glutathione beads were incubated with MDCK cell lysates, washed, and the attached proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and recognized with antibodies against vinculin (upper panel). TCL denotes a sample of total cell lysates. The amounts of GST proteins employed were constant in these experiments as demonstrated by the Coomassie-stained gel in the lower panel. C, α-catenin vinculin binding site (VBS) shares sequence similarity with other VBSs. The α-catenin VBS is aligned with two IpaA VBSs, three talin VBSs, and one α-actinin VBS using ClustalW. Hydrophobic residues conserved in at least five VBSs are in bold and italicized. The orientation of α-actinin VBS is inverted as reported previously (19). D, α-catenin VBS is predicted to be amphipathic α-helix based on amino acid sequence (27). The α-catenin VBS (amino acids 328–349) was arranged around a helical wheel, which revealed the helix has a hydrophilic face and a hydrophobic face. Hydrophilic residues are shown as circles, hydrophobic residues as diamonds, potentially negatively charged residues as triangles, and potentially positively charged as pentagons.

Cell Lines and Transfection

HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a 10% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. For transfection, HEK 293 cells were seeded on 0.1% gelatin-coated 100-mm dishes at 3 million cells per plate. Cells were transfected with 3 μg of pEGFP-V1–1066 or pEGFP-V1–1066 A50I using Lipofectamine/Plus reagent (Invitrogen).

FRET Assay of TP3 in Cell Lysates

Cell lysate was made (20) from HEK 293 cells expressing TP3 or TP3A50I. The FRET assays were performed as previously described (20, 22) using various concentrations of wild type or mutant α-catenins and 5 μm actin. The emission spectra of fluorescent proteins in the lysate were acquired at 20 °C with a Fluoromax-3 spectrofluorimeter (Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ). Cerulean emission was traced from 460 to 600 nm with excitation at 440 nm, and Citrine emission was traced from 510 to 600 nm with excitation at 490 nm. The increment was 1 nm, and integration was 0.2 s. The excitation and emission slit widths were 3 mm and 5 mm, respectively. Lysate from an equal number of untransfected HEK293 cells was used to obtain a background emission spectrum.

Determination of the Corrected FRET Emission Ratio, SE/Fda

The raw FRET signal is the Citrine emission (peak at 525) stimulated by excitation of Cerulean at 440 nm. It consists of the sensitized emission (SE),3 the emission from direct excitation of citrine by 440 nm, and the overlap of the cerulean emission spectrum with the citrine emission spectrum. The latter two components of the raw FRET signal are referred to as “spectral cross-talk”. The amount of spectral cross-talk was determined as previously described (20) and used to correct the raw FRET data. The corrected FRET emission ratio (ER) is the ratio of the sensitized emission at 525 nm to the emission at 475 nm, after correcting for the citrine and cerulean cross-talk. ER is SE/Fda, where SE is the sensitized emission and Fda is the fluorescence of the donor in the presence of the acceptor. SE/Fda correlates directly with FRET efficiency (20); the higher the SE/Fda, the stronger the FRET. FRET results are plotted as the SE/Fda ratio.

Protein Purification

Recombinant GST, GST-FL α-catenin, GST-α-catenin truncations, His6-tagged α-catenin 273–510, His6-tagged α-catenin 273–510 L344P, and His6-tagged β-catenin 1–131 were purified by affinity chromatography. After elution, all the proteins were dialyzed against FP buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.6, 100 mm NaCl). Proteins were concentrated using the Amicon Ultra 3,000 MWCO system (Millipore) and stored at 4 °C.

Pull-down Assay

50 μg of purified GST, or GST-FL α-catenin, or GST-α-catenin truncations bound to the glutathione-Sepharose were incubated with MDCK cell lysate at 4 °C for 1.5 h. The recovered proteins were washed, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blotting.

In Vitro Binding Assay

Purified GST, GST-α-catenin 273–510, GST-α-catenin 273–510 L344P, GST-FL α-catenin, or GST-FL α-catenin L344P (5 μm) was incubated with 1.5 μm His6-vinculin 1–398 or His6-vinculin 1–398 A50I in binding buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 100 mm KCl, 0.2 mm EGTA, 4 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm DTT, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mm PMSF) at room temperature for 30 min. The mixture was then incubated with glutathione-Sepharose, that had been preincubated with 5 μm BSA at 4 °C for 30 min. The recovered proteins were washed, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blotting.

Actin Co-sedimentation Assay

HEK 293 cells were detached with 1 mm EDTA in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS at 37 °C for 20 min. The pelleted cells were resuspended in ice-cold hypotonic buffer (100 mm KCl, 20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EGTA, 0.5 mm ATP, 0.5 mm DTT, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 mm Na3VO4, and 1 mm PMSF) and at a density of 2 to 4 × 106 cells/ml, incubated on ice for 20 min, and homogenized manually. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 4 °C, 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and then subjected to another centrifugation at 25 °C, 80,000 rpm for 30 min. Lysates were mixed with designated purified protein at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were spun at 25 °C, 80,000 rpm for 30 min. Equivalent amounts of total sample before spin (T), supernatant (S), and pellet (P) fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and recognized with hVIN1 and C4 monoclonal antibodies to vinculin (Sigma) and actin (Millipore), respectively. The amount of GFP-tagged vinculin in the pellet to the total (pellet/total) was quantified using densitometry and expressed as a ratio. The data presented in the graph are the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments.

GFP Depletion Assay

HEK293 cells were lysed as described in actin cosedimentation assay. The cell lysate containing GFP-V1–851 or GFP-V1–851 A50I was incubated with increasing concentration of His6-tagged α-catenin 273–510 for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with Ni-NTA-agarose. The unbound GFP-V1–851 or GFP-V1–851 A50I was separated from the bound fraction by centrifugation and assayed for concentration by spectrofluorimetry. The fraction of GFP-V1–851 or GFP-V1–851 A50I in complex with α-catenin 273–510 was plotted against unbound protein. Data were fitted to the equation Bmax × X/(Kd + X) using Sigmaplot software, where Bmax = maximum fraction of receptor capable of binding to ligand. The data presented in the graph are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

Vinculin Activation Assay

1 μm purified His-tagged α-catenin 273–510, 1 μm full-length vinculin, and 5 μm skeletal muscle F-actin were mixed together in binding buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl, 0.2 mm EGTA, 0.5 mm ATP, 0.5 mm DTT, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mm PMSF) at room temperature for 30 min. The mixtures were then incubated with GST Vinexin (amino acids 42–155) bound to glutathione beads that had been blocked with 5 μm BSA overnight at 4 °C. The samples were centrifuged and the supernatant harvested and saved as the soluble (S) fraction. The beads were then washed and the pellet (P) was recovered. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

HEK293 cells were lysed as described in the actin cosedimentation assay. Cell lysates were incubated with indicated purified protein(s) for 1 h at room temperature. GFP was then immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal GFP antibody (Roche) at 4 °C, and the immunoprecipitates were washed four times in lysis buffer, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF, and subjected to Western blot analysis with the appropriate antibody: the p34-Arc subunit of the Arp2/3 complex was blotted using a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide that encompassed amino acids 179–204 of p34-Arc (25). Ponsin was blotted using a rabbit antibody raised against synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 192–206 of human CAP (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions). GFP was blotted with a mouse monoclonal antibody (Roche). Actin was blotted with a mouse monoclonal antibody (clone C4, MP Biomedicals). The blots were developed using ECL Western blot detection reagents (Pierce), and the signal was detected on x-ray film (Kodak).

RESULTS

Vinculin Is Activated by α-Catenin and F-Actin

In adherens junctions α- and β-catenin bind to the vinculin head domain suggesting that one or both of these proteins might activate vinculin (24, 26). We tested whether vinculin is activated by either catenin. When vinculin is activated, it binds to actin filaments (16, 22). Consequently, vinculin activation has reliably been measured by examining the ability of vinculin to co-sediment with actin filaments (16, 20, 22). We examined whether α- or β-catenin could induce vinculin to co-sediment with actin filaments. For most of these studies, we employed an α-catenin fragment 273–510 that binds vinculin because the full-length protein forms intramolecular interactions that preclude access to the vinculin binding site (27, 28). Also, full-length α-catenin dimer binds actin and this would prevent knowing whether a ternary complex of vinculin, α-catenin, and actin is present in pellets of actin co-sedimentation assays. When cell lysate containing full length EGFP-vinculin was incubated with purified actin filaments and then centrifuged at speeds sufficient to sediment actin filaments, little to no vinculin co-sedimented with actin filaments alone (Fig. 1, A and C and Ref. 22). The addition of α-catenin 273–510 to the mixtures of vinculin and actin triggered large amounts of vinculin to pellet with actin filaments (Fig. 1, A and C). This effect was specific for α-catenin as little or no vinculin sedimented when β-catenin was added (Fig. 1B).

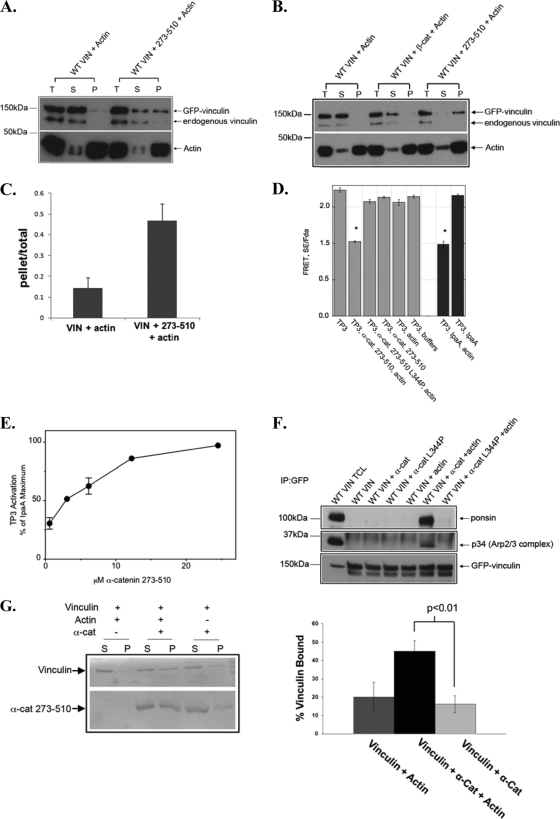

FIGURE 1.

α-Catenin, but not β-catenin, activates vinculin. A–C, α-catenin, but not β-catenin, activates vinculin in an actin co-sedimentation assay. A and B, HEK293 cells expressing GFP-tagged full-length vinculin (WT VIN) were lysed, and the lysates were clarified of endogenous actin filaments by high speed centrifugation and then incubated with 5 μm actin filaments (WT VIN +Actin), 5 μm actin filaments and in panel A with 10 μm α-catenin 273–510 (WT VIN+ 273–510 + Actin) or in panel B with 10 μm β-catenin 1–131 (WT VIN + β-cat + Actin). The actin filaments were pelleted by centrifugation. Equivalent amounts of sample before centrifugation (T), or the supernatant (S) or the pellet (P) fractions obtained after centrifugation were recognized with antibodies against vinculin and actin. C, the amount of GFP-tagged vinculin in the pellet and the total sample prior to centrifugation was quantified and expressed a ratio of the pellet/total. The data presented in the graph are the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. D and E, α-catenin triggers the vinculin FRET probe to adopt an actin-binding conformation. D, FRET assays were performed on cell lysates from HEK 293 cells transfected with a vinculin FRET probe (TP3) and treated with indicated proteins. As a positive control, lysates were treated with IpaA (5 μm) and actin (5 μm). As a negative control the lysates were treated with buffer (TP3, buffers), actin alone (TP3, actin), α-catenin alone (TP3, α-cat 273–510), or IpaA alone (TP3, IpaA). Raw FRET ratios were obtained and corrected for spectral cross-talk to yield SE/Fda, as described in Ref. 20 and briefly under “Experimental Procedures.” The plot is the mean of three independent experiments ± S.E.; *, p < 0.0001. E, α-catenin activates vinculin in a concentration dependent manner. Cell lysates containing TP3 were supplemented with 2 mm MgCl2, 5 μm of G-actin and increasing amounts of α-catenin 273–510 and then incubated for 3 h at 20 °C to allow actin polymerization and protein interactions to achieve equilibrium. FRET was measured and SE/Fda was calculated. Graph is an average of n = two independent experiments ± S.D. The maximum change in TP3 SE/Fda elicited by a saturating amount (5 μm) of IpaA and 5 μm actin was 0.77. The first point on the graph is 0.6 μm α-catenin and 5 μm actin. Controls were as in 1D. F, co-immunoprecipitation assay to test vinculin activation. Lysates from HEK293 cells expressing GFP-tagged full-length vinculin (WT VIN) were prepared as described in A and incubated with α-catenin 273–510 (α-cat), or α-catenin 273–510 mutant (α-cat L344P), or actin filaments (actin) alone or in combination as indicated. GFP immunoprecipitates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and recognized with an antibody against ponsin or the p34-Arc subunit of the Arp2/3 complex. The blot was stripped and re-probed for GFP. TCL denotes a sample of total cell lysates. G, activation studies using purified proteins, rather than cell lysates. Left panel, vinculin, at a 1 μm concentration, was incubated with GST-vinexin immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads in the presence of α-catenin 273–510 (1.0 μm α-cat) and/or F-actin. After an overnight incubation the supernatant (S) and pellet (P) were fractionated by centrifugation. Equal loading of pellets and supernatants represent 10% of total reaction. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. Right panel, quantification of four independent experiments examining the vinculin-vinexin interaction. In the presence of α-catenin 273–510 alone, some vinculin sediments with GST-vinexin and the addition of F-actin greatly enhances this effect.

Similar results were found in parallel experiments using FRET probes that report on vinculin activation and actin-binding in cell lysates (16, 20, 22). For these studies, we employed a vinculin FRET probe, TP3, that contains Citrine inserted before the tail domain and Cerulean on the C terminus, in place of YFP and CFP in the original TP2 construct (20). When vinculin is in the closed conformation, the two fluorophores in this probe are in close contact, which gives a high FRET signal; after vinculin activation and binding to actin, the FRET signal reduces because the binding of actin to vinculin tail domain forces the two fluorophores away from one another (20). We found that the FRET probe has a strong fluorescent signal by itself; the addition of 5 μm actin filaments alone, or purified α-catenin 273–510 had little effect on the FRET signal (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the addition of both actin filaments and α-catenin 273–510 induced a significant reduction in the FRET signal (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, α-catenin activation of vinculin was dose dependent with a half-maximal activation observed at 3 μm α-catenin 273–510 (Fig. 1E). Like wild type vinculin, the vinculin FRET probe also co-sediments with actin in the presence of α-catenin or IpaA (supplemental Fig. S1). Thus, α-catenin activates vinculin.

To determine whether α-catenin 273–510 activates vinculin for binding to its ligands and to evaluate whether actin is required for this event, we tested whether vinculin bound ponsin, a component of the nectin based adhesions, or the Arp2/3 complex, a potent nucleator of actin polymerization. Both of these ligands bind to sites in the proline-rich region of vinculin and previous studies show that vinculin co-immunoprecipitates with these proteins only when its inactivating intramolecular head-tail interaction has been relieved (12, 29). In the absence of α-catenin 273–510 or actin filaments, neither ponsin nor the Arp2/3 complex was recovered with vinculin immunoprecipitates (Fig. 1F). In the presence of both α-catenin 273–510 and actin, ponsin, and the Arp2/3 complex were recruited to vinculin (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these results show that α-catenin activates vinculin for binding to Arp2/3 and ponsin and that this activation requires actin filaments.

To ensure that vinculin activation by α-catenin did not require other proteins present in the cell lysates, we tested whether the activation could be recapitulated in vitro using purified proteins. We monitored activation by examining vinculin binding to the SH3 domain of vinexin. We found that only a small fraction of vinculin bound vinexin when α-catenin 273–510 alone or F-actin alone were present. When both α-catenin and F-actin were present, a large percentage of vinculin bound to GST-vinexin (Fig. 1G). These results indicate that purified α-catenin activates vinculin and rules out the possibility that other constituents of the lysates are responsible (Fig. 1G). Hence, α-catenin, like talin, employs a combinatorial mechanism to fully activate vinculin.

Generation of an α-Catenin Point Mutant That Blocks Vinculin Binding and Activation

To explore whether direct binding of α-catenin to vinculin is required for activation, we considered generating a mutant form of α-catenin that could not bind vinculin. We mapped the vinculin-binding site on α-catenin using a series of α-catenin fragments expressed as GST fusion proteins (Fig. 2A). Previous studies showed vinculin binds to a region of α-catenin that contains amino acids 273–510 (27). Using our α-catenin GST fusions, we confirmed the presence of a vinculin binding site in this region and further mapped the site to amino acids 326–377 of α-catenin (Fig. 2B). This region of α-catenin has been predicted to contain one α-helix (Fig. 2D). Alignment of the vinculin binding sites (VBSs) in talin, IpaA, and α-actinin revealed that these proteins possess an amphipathic α-helix with several conserved hydrophobic residues (Fig. 2C). The α-helix of α-catenin that binds to vinculin also has these features (Fig. 2, C and D). Substitution of proline for leucine 344 blocked vinculin binding to an α-catenin fragment (273–510) and to full-length α-catenin (Fig. 3A).

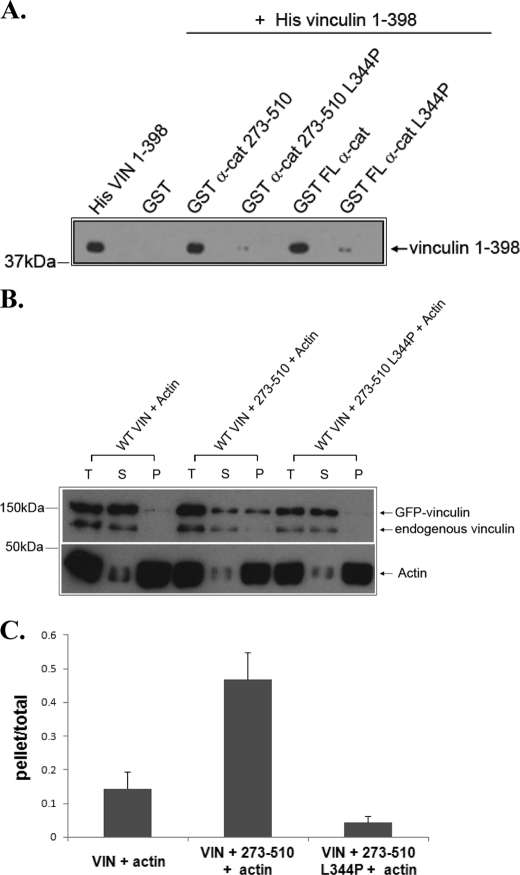

FIGURE 3.

Substitution of L344P in α-catenin blocks vinculin binding and activation. A, substitution of L344P blocks in vitro binding of α-catenin to vinculin. His-vinculin head domain (His VIN 1–398) was incubated with purified GST or wild-type or mutant α-catenin in binding buffer. The protein complexes were recovered using glutathione beads, washed, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with an antibody against His. FL indicates full-length α-catenin. B and C, substitution of L344P in α-catenin blocks vinculin co-sedimentation with actin. HEK293 cells expressing GFP-tagged full-length vinculin (WT VIN) were lysed, clarified by centrifugation, and then incubated with the indicated proteins with the same concentration as described in Fig. 1A. The mixtures were analyzed as described in Fig. 1A, and the resulting immunoblot is shown in B. The amount of GFP-tagged vinculin in the pellet and the total sample prior to centrifugation was quantified and expressed a ratio of the pellet/total as described in Fig. 1. The data presented in the graph are the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments.

We then tested whether mutation of L344P abolishes α-catenin 273–510 activation of vinculin. The mutant α-catenin did not induce vinculin co-sedimentation with actin filaments (Fig. 3, B and C, supplemental Fig. S2), and it did not trigger a reduction of FRET signal (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, the mutant α-catenin did not induce ponsin or the Arp2/3 complex to co-immunoprecipitate with vinculin (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these findings indicate that direct binding of α-catenin to vinculin is required for vinculin activation, and substitution of α-catenin L344P blocks this effect.

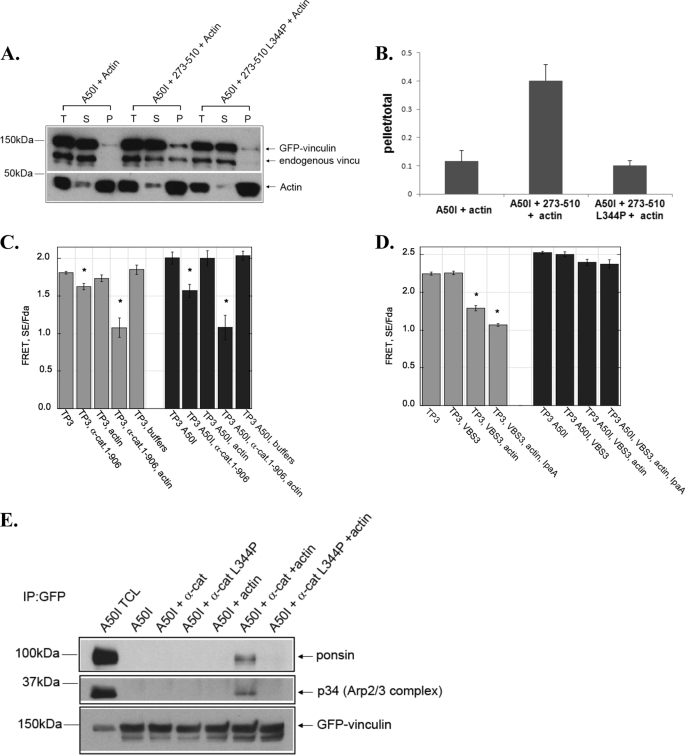

Vinculin Activation by α-Catenin and F-actin Is Independent of Vinculin A50

All of the known vinculin activators contact amino acid A50 lying within the hydrophobic groove between helices α1 and α2 in the vinculin head (17). We tested whether activation of vinculin by α-catenin could be blocked by the A50I substitution which blocks IpaA, talin, and talin VBSs from binding to vinculin (15, 16). Surprisingly, α-catenin activated A50I vinculin in all of the assays we used (Fig. 4, A–C, E). This observation is in contrast to IpaA and talin, both of which completely fail to activate vinculin in the presence of an A50I substitution (Fig. 4D). These effects were not due to the usage of a fragment of α-catenin, because full-length α-catenin activated the TP3 vinculin FRET probe (Fig. 4C). In contrast to α-catenin 273–510, the addition of full-length α-catenin alone partially activated vinculin and the addition of actin further enhanced this activation (Fig. 4C). Similar results were obtained when α-catenin was added to TP3 A50I vinculin FRET probe (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, the ability of α-catenin to activate TP3 vinculin A50I was not due to an artifact of the probe as this mutation blocked activation stimulated by IpaA and VBS3 (Fig. 4D). Thus, α-catenin is the first known protein that is able to activate vinculin containing the A50I point mutation.

FIGURE 4.

α-catenin activates vinculin independently of the vinculin A50 residue. A and B, α-catenin triggers vinculin to co-sediment with actin filaments in the presence of an A50I substitution in vinculin. Lysates from cells expressing a GFP-tagged full-length vinculin harboring an A50I substitution prepared as described in the legend of Fig. 1A, and then incubated with 5 μm actin filaments (A50I +Actin), 10 μm His6-tagged α-catenin 273–510 and 5 μm actin filaments (A50I + 273–510 + Actin), or 10 μm His6-tagged α-catenin 273–510 L344P and 5 μm actin filaments (A50I+ 273–510 L344P + Actin). The mixtures were analyzed as described in the legend of Fig. 1A and the resulting immunoblot is shown in A. The immunoblot bands were quantified and expressed as described in Fig. 1. The graph in B represents the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. C, full-length α-catenin induces activating conformation changes in WT vinculin and vinculin A50I. Cell lysates from HEK 293 cells transfected with vinculin probe TP3 (gray bars) or TP3 A50I (black bars) were treated with indicated proteins. The concentration for full-length α-catenin is 8 μm, and actin is 5 μm. The FRET SE/Fda was obtained as described in Ref. 20 and “Experimental Procedures.” Plots are an average of n = 3 ± S.E. D, VBS3 and IpaA do not induce activating conformational changes in Vinculin A50I. Cell lysates were treated with VBS3(4 μm) or IpaA (4 μm) and actin (5 μm). Plots are the mean of n = 3 ± S.E. E, α-catenin induces vinculin A50I to bind to conformation specific ligands. The co-immunoprecipitation of vinculin A50I with ponsin or the Arp2/3 complex was assessed as described in Fig. 1F. TCL denotes a sample of total cell lysates.

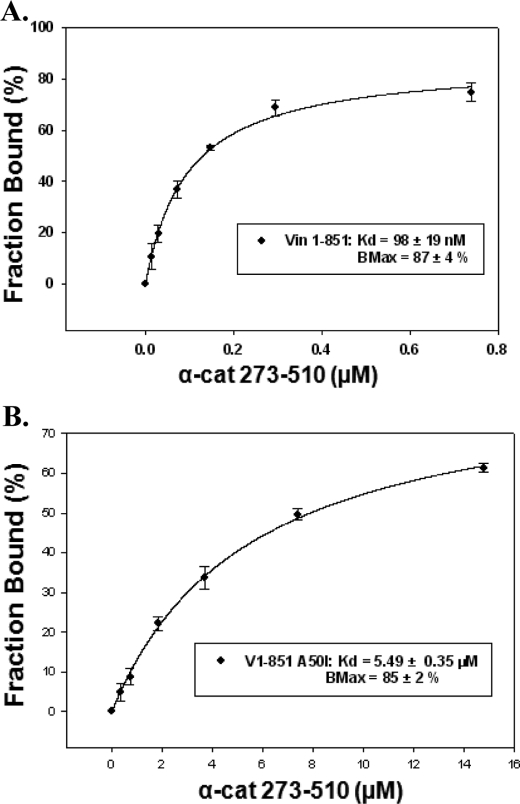

To determine whether the A50I substitution affected α-catenin binding to vinculin, the dissociation constant for this interaction was measured. For these studies, we used the GFP depletion assay which is commonly used in the field to analyze binding affinities between vinculin and its binding partners. This approach uses GFP-tagged vinculin proteins that are transiently expressed in HEK293 cells to ensure proper protein folding as well as post-translational modification. Increasing amounts of purified His-tagged α-catenin fragment were titrated into cell lysate and recovered with Ni-NTA agarose. The decrease of GFP fluorescence in the cell lysate was monitored by fluorimeter. The data were then plotted and fitted to a single binding site equation. We found that α-catenin 273–510 binds to vinculin head domain with a Kd of 98 ± 19 nm. This result is in good agreement with the previously reported value obtained using isothermal titration calorimetry (Fig. 5A and Ref. 15). A50I mutation reduced α-catenin binding to a Kd of 5.49 ± 0.35 μm (Fig. 5B). In further support of α-catenin binding to vinculin harboring this mutation, α-catenin could be co-immunoprecipitated with vinculin A50I (8). While α-catenin binds A50I with a lower binding affinity, the observation that it is still able to activate vinculin is in stark contrast with what has been observed with talin, which does not co-precipitate with vinculin A50I and binds with affinity that is too weak to be measured in pull-down assays (Kd > 20 μm) (22). Collectively, these data suggest that α-catenin activates vinculin independently of contacting residue A50, and employs a mechanism and vinculin interface that is distinct from those used by talin and IpaA.

FIGURE 5.

Biochemical analysis of the vinculin-α-catenin interaction. A and B, α-catenin binds vinculin A50I with a lower affinity than the wild type protein. GFP depletion assays were used to measure the dissociation constant (Kd) for (A) vinculin head domain (1–851) binding to an α-catenin fragment (273–510), or (B) vinculin head mutant (1–851 A50I) binding to an α-catenin fragment (273–510). Lysates from HEK293 cells expressing GFP-V1–851 or GFP-V1–851 A50I were incubated with increasing concentrations of His6-tagged α-catenin 273–510, and the proteins were recovered with Ni-NTA-agarose. The unbound GFP-V1–851 or GFP-V1–851 A50I was separated from the bound fraction by centrifugation and assayed for concentration by spectrofluorimetry. The fraction of GFP-V1–851 or GFP-V1–851 A50I in complex with α-catenin 273–510 was plotted against unbound protein. Data were fitted to the equation Bmax × X/(Kd + X) using Sigmaplot software, where Bmax = maximum fraction of receptor capable of binding to ligand. The data presented in the graph are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

One challenge to understanding how dynamic changes in cell-cell adhesion are achieved is to identify the cadherin adhesion complex proteins that are essential and to pinpoint mechanisms for regulating their activities. Vinculin is critical for E-cadherin function, but little is known about how it is regulated at this site. Here, we show that α-catenin is an adherens junction component that induces activating conformational changes in vinculin (Fig. 1). This effect is specific for α-catenin as another adherens junctions component, β-catenin, does not activate vinculin (Fig. 1B). Unlike talin which activates vinculin in focal adhesions, α-catenin functions independently of an A50 residue in the vinculin head, which forms part of the binding site for talin and IpaA, suggesting the presence of a distinct molecular mechanism for vinculin activation (Fig. 4).

We considered whether α-catenin 273–510 is as efficient at activating full length vinculin as other known ligands. The FRET vinculin activation assay showed that α-catenin 273–510 achieved half-maximal activation at 3 μm α-catenin (Fig. 1E). In published titration studies, 2.9 μm talin rod domain, 0.48 μm VBS3, and 82 nm IpaA were required for half-maximum activation of the HP3 vinculin FRET probe (22). These data indicate that α-catenin 273–510 activates vinculin as efficiently as talin rod domain. In support of this notion, the rod domain of talin binds to vinculin 1–851 with a Kd ∼ 99 nm (22, 30), and α-catenin 273–510 binds to vinculin 1–851 with a Kd = 98 ± 19 nm (Fig. 5). The difference in the binding affinities of vinculin and α-catenin domains for each other versus the concentration of α-catenin 273–510 required for half-maximum activation of full-length vinculin FRET probes reflect the difference in accessibility of ligand binding sites on autoinhibited full-length vinculin (15, 16, 22).

While talin, IpaA, and α-catenin activate vinculin, they seem to employ at least two distinct molecular mechanisms for activation. Talin and α-catenin 273–510 bind to vinculin head domain and require actin filaments to bind to the tail domain to form stable complexes with vinculin (Fig. 1 and Ref. 22). In contrast, IpaA (22) and full-length α-catenin activate vinculin in the absence of any exogenously added ligand, although addition of actin increases the extent of activation in both cases. In addition to distinct requirements for actin, the known activators bind to partially distinct regions of vinculin. Specifically, substitution of A50I in the vinculin head domain completely abolishes both talin and IpaA binding and vinculin activation (22). However, this mutant version of vinculin still binds α-catenin, albeit with a lower affinity. Importantly, α-catenin can still activate A50I vinculin (Fig. 4), even though its affinity is reduced ∼50-fold (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that there are at least two distinct mechanisms for activating vinculin: 1) ligand binding to the A50 groove in the vinculin head and actin filament binding to the tail, and 2) ligand binding independently of A50 with a requirement for actin filaments.

At first glance, the idea that there are two distinct mechanisms for activating vinculin is somewhat surprising given that all three ligands possess and employ an amphipathic α-helix with shared structural characteristics for vinculin binding and activation (Fig. 2C and Ref. 30). However considering that vinculin is comprised almost exclusively of α-helical bundles with similar structural features, it is reasonable to believe that these amphipathic α-helices could bind to more than one region of the molecule (15, 31). Thus, it is likely that there is more than one surface on vinculin that is required for its activation. In support of this notion, both talin and IpaA have multiple vinculin binding sites that could potentially interact with more than one region of vinculin. Also IpaA binds to two distinct sites on vinculin (32). We attempted to identify an additional α-catenin binding site on vinculin, but have been unable to detect α-catenin binding to vinculin regions other than 1–258 amino acids. It is possible that the second site lies within this region and/or has a low affinity for ligands or is cooperative with the first site.

Irrespective of the mechanism(s) by which α-catenin activates vinculin, interaction of these proteins is critical for adherens junction function. It has long been thought that α-catenin localizes vinculin to adherens junctions owing to the observation that vinculin is lost from adherens junctions when α-catenin is deleted from cells (24, 33). However, the requirement for α-catenin to localize vinculin to adherens junctions has not been universally supported. For example, work by Hazan et al. (23) showed that in cell lines lacking α-catenin, vinculin co-precipitated with β-catenin-E-cadherin complexes. Similarly, we found that mutant versions of vinculin that were devoid of β-catenin binding, but retained α-catenin binding, did not localize to adherens junctions (8). Hence in some contexts, vinculin localizes to adherens junctions independently of α-catenin. We believe that these conflicting observations may be explained by the fact that α-catenin does not localize vinculin to adherens junctions but does activate it at this site. In this scenario, cells lacking α-catenin would not be expected to have vinculin in adherens junctions as a result of vinculin not being activated and stabilized at this site. Alternatively vinculin might be present but the antibodies used to detect it did not recognize the autoinhibited conformation of vinculin.

The new finding that α-catenin and actin cooperate to activate vinculin combined with our previous observation that β-catenin localizes vinculin to adherens junctions (8) allow for a revised model for vinculin recruitment and activation in adherens junctions to be proposed. According to this model, upon initiation of adherens junction assembly, β-catenin localizes vinculin to adherens junctions where it is bound and activated by the combined effects of α-catenin and actin. The subsequent unfurling of vinculin allows its numerous interacting proteins to bind and modulate the assembly and maturation of adherens junctions and E-cadherin mechanosensing (8–11, 34, 35).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thuy Hoang for performing some of the FRET experiments. We are grateful to David Rimm for the generous gift of reagents, and to Peter Rubenstein and members of the DeMali Laboratory for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 1K01CA111818 and American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant 115274 (to K. A. D.), National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM041605 (to S. W. C.), and American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship 0910127G (to X. P.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- SE

- sensitized emission

- ER

- emission ratio

- VBS

- vinculin binding site.

REFERENCES

- 1. Takeichi M., (1995) Morphogenetic roles of classic cadherins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7, 619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim S. H., Jen W. C., De Robertis E. M., Kintner C. (2000) The protocadherin PAPC establishes segmental boundaries during somitogenesis in Xenopus embryos. Curr. Biol. 10, 821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tepass U., Godt D., Winklbauer R. (2002) Cell sorting in animal development: signaling and adhesive mechanisms in the formation of tissue boundaries. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 572–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gumbiner B. M., (2005) Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 622–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nusrat A., Turner J. R., Madara J. L. (2000) Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions. IV. Regulation of tight junctions by extracellular stimuli: nutrients, cytokines, and immune cells. Am. J. Physiol.. Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 279, G851–G857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Venkiteswaran K., Xiao K., Summers S., Calkins C. C., Vincent P. A., Pumiglia K., Kowalczyk A. P. (2002) Regulation of endothelial barrier function and growth by VE-cadherin, plakoglobin, and β-catenin. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 283, C811–C821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Niessen C. M., Gottardi C. J. (2008) Molecular components of the adherens junction. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778, 562–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peng X., Cuff L. E., Lawton C. D., DeMali K. A. (2010) Vinculin regulates cell surface E-cadherin expression by binding to β-catenin. J. Cell Science 123, 567–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zemljic-Harpf A. E., Miller J. C., Henderson S. A., Wright A. T., Manso A. M., Elsherif L., Dalton N. D., Thor A. K., Perkins G. A., McCulloch A. D., Ross R. S. (2007) Cardiac myocyte-specific excision of the vinculin gene disrupts cellular junctions, causing sudden death or dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol. Cell. Biology 27, 7522–7537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maddugoda M. P., Crampton M. S., Shewan A. M., Yap A. S. (2007) Myosin VI and vinculin cooperate during the morphogenesis of cadherin cell cell contacts in mammalian epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 178, 529–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. le Duc Q., Shi Q., Blonk I., Sonnenberg A., Wang N., Leckband D., de Rooij J. (2010) Vinculin potentiates E-cadherin mechanosensing and is recruited to actin-anchored sites within adherens junctions in a myosin II-dependent manner. J. Cell Biol. 189, 1107–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeMali K. A., Burridge K. (2003) Coupling membrane protrusion and cell adhesion. J. Cell Sci. 116, 2389–2397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Humphries J. D., Wang P., Streuli C., Geiger B., Humphries M. J., Ballestrem C. (2007) Vinculin controls focal adhesion formation by direct interactions with talin and actin. J. Cell Biol. 179, 1043–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson R. P., Craig S. W. (1995) F-actin binding site masked by the intramolecular association of vinculin head and tail domains. Nature 373, 261–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bakolitsa C., Cohen D. M., Bankston L. A., Bobkov A. A., Cadwell G. W., Jennings L., Critchley D. R., Craig S. W., Liddington R. C. (2004) Structural basis for vinculin activation at sites of cell adhesion. Nature 430, 583–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen D. M., Chen H., Johnson R. P., Choudhury B., Craig S. W. (2005) Two distinct head-tail interfaces cooperate to suppress activation of vinculin by talin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17109–17117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Izard T., Evans G., Borgon R. A., Rush C. L., Bricogne G., Bois P. R. (2004) Vinculin activation by talin through helical bundle conversion. Nature 427, 171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Izard T., Vonrhein C. (2004) Structural basis for amplifying vinculin activation by talin. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 27667–27678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bois P. R., Borgon R. A., Vonrhein C., Izard T. (2005) Structural dynamics of α-actinin-vinculin interactions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6112–6122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 20. Chen H., Cohen D. M., Choudhury D. M., Kioka N., Craig S. W. (2005) Spatial distribution and functional significance of activated vinculin in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 169, 459–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bois P. R., O'Hara B. P., Nietlispach D., Kirkpatrick J., Izard T. (2006) The vinculin binding sites of talin and α-actinin are sufficient to activate vinculin. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 7228–7236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen H., Choudhury D. M., Craig S. W. (2006) Coincidence of actin filaments and talin is required to activate vinculin. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 40389–40398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hazan R. B., Kang L., Roe S., Borgen P. I., Rimm D. L. (1997) Vinculin is associated with the E-cadherin adhesion complex. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32448–32453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Watabe-Uchida M., Uchida N., Imamura Y., Nagafuchi A., Fujimoto K., Uemura T., Vermeulen S., van Roy F., Adamson E. D., Takeichi M. (1998) α-Catenin-vinculin interaction functions to organize the apical junctional complex in epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 142, 847–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DeMali K. A., Barlow C. A., Burridge K. (2002) Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin: coupling membrane protrusion to matrix adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 159, 881–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weiss E. E., Kroemker M., Rüdiger A. H., Jockusch B. M., Rüdiger M. (1998) Vinculin is part of the cadherin-catenin junctional complex: complex formation between α-catenin and vinculin. J. Cell Biol. 141, 755–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Janssen M. E., Kim E., Liu H., Fujimoto L. M., Bobkov A., Volkmann N., Hanein D. (2006) Three-dimensional structure of vinculin bound to actin filaments. Mol. Cell 21, 271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yonemura S., Wada Y., Watanabe T., Nagafuchi A., Shibata M. (2010) α-Catenin as a tension transducer that induces adherens junction development. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 533–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mandai K., Nakanishi H., Satoh A., Takahashi K., Satoh K., Nishioka H., Mizoguchi A., Takai Y. (1999) Ponsin/SH3P12: an l-afadin- and vinculin-binding protein localized at cell-cell and cell-matrix adherens junctions. J. Cell Biol. 144, 1001–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Izard T., Tran Van Nhieu G., Bois P. R. (2006) Shigella applies molecular mimicry to subvert vinculin and invade host cells. J. Cell Biol. 175, 465–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Borgon R. A., Vonrhein C., Bricogne G., Bois P. R., Izard T. (2004) Crystal structure of human vinculin. Structure 12, 1189–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nhieu G. T., Izard T. (2007) Vinculin binding in its closed conformation by a helix addition mechanism. The EMBO J. 26, 4588–4596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sheikh F., Chen Y., Chen Y., Liang X., Hirschy A., Stenbit A. E., Gu Y., Dalton N. D., Yajima T., Lu Y., Knowlton K. U., Peterson K. L., Perriard J. C., Chen J. (2006) α-E-catenin inactivation disrupts the cardiomyocyte adherens junction, resulting in cardiomyopathy and susceptibility to wall rupture. Circulation 114, 1046–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peng X., Nelson E. S., Maiers J. L., DeMali K. A. (2011) New insights into vinculin function and regulation. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 287, 191–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zemljic-Harpf A. E., Ponrartana S., Avalos R. T., Jordan M. C., Roos K. P., Dalton N. D., Phan V. Q., Adamson E. D., Ross R. S. (2004) Heterozygous inactivation of the vinculin gene predisposes to stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 1033–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.