Background: microRNAs (miRNAs) are closely related to osteogenesis.

Results: miR-30 family members (miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d) mediate the inhibition of osteogenesis by targeting Smad1 and Runx2.

Conclusion: miR-30 family members are key negative regulators of BMP-2-mediated osteogenic differentiation.

Significance: These findings may provide new insights into understanding the regulatory role of miRNAs in the process of osteogenic differentiation.

Keywords: Bone, Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), MicroRNA, Osteoblasts, SMAD Transcription Factor

Abstract

miRNAs are endogenously expressed 18- to 25-nucleotide RNAs that regulate gene expression through translational repression by binding to a target mRNA. Recently, it has been indicated that miRNAs are closely related to osteogenesis. Our previous data suggested that miR-30 family members might be important regulators during the biomineralization process. However, whether and how they modulate osteogenic differentiation have not been explored. In this study, we demonstrated that miR-30 family members negatively regulate BMP-2-induced osteoblast differentiation by targeting Smad1 and Runx2. Evidentially, overexpression of miR-30 family members led to a decrease of alkaline phosphatase activity, whereas knockdown of them increased the activity. Then bioinformatic analysis identified potential target sites of the miR-30 family located in the 3′ untranslated regions of Smad1 and Runx2. Western blot analysis and quantitative RT-PCR assays demonstrated that miR-30 family members inhibit Smad1 gene expression on the basis of repressing its translation. Furthermore, dual-luciferase reporter assays confirmed that Smad1 is a direct target of miR-30 family members. Rescue experiments that overexpress Smad1 and Runx2 significantly eliminated the inhibitory effect of miR-30 on osteogenic differentiation and provided strong evidence that miR-30 mediates the inhibition of osteogenesis by targeting Smad1 and Runx2. Also, the inhibitory effects of the miR-30 family were validated in mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Therefore, our study uncovered that miR-30 family members are key negative regulators of BMP-2-mediated osteogenic differentiation.

Introduction

microRNAs (miRNAs)3 consisting of 18–25 nucleotides belong to the single-stranded small non-coding RNA family (1–6). They bind to the 3′ UTR of specific target genes and regulate expression of the target genes by promoting the degradation of transcribed mRNAs or by inhibiting their translation (7). Recent studies indicate that miRNAs are important players during the osteogenic differentiation (8–18).

In a previous study, we investigated the expression profiles of miRNAs in MC3T3-E1 cells treated with Emdogain®, a clinical mixture of enamel matrix proteins that can induce biomineralization and osteogenesis (19–23). The data indicated that the expression levels of some miR-30 family members, such as miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d, were significantly down-regulated during the osteoblast differentiation. Studies by others also found that miR-30a and miR-30d are down-regulated during BMP-2-induced osteogenesis of C2C12 mesenchymal cells (15). Considering that miR-30 family members decreased during osteogenesis induced by different stimuli, it is possible that they may play important roles in the process.

Here we investigated the effects of the miR-30 family on osteoblastic differentiation. We found that miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d expression was down-regulated during BMP-2 stimulation. They were demonstrated to inhibit osteoblast differentiation. Further studies identified Smad1 and Runx2 as common target genes of miR-30 family members. Finally, rescue experiments showed that overexpression of Smad1 and Runx2 significantly eliminated the inhibitory effect of miR-30 on osteogenic differentiation. All these data indicate that miR-30 family members function as negative regulators of osteoblastic differentiation by targeting the master osteogenic transcription factors Smad1 and Runx2. These findings may provide new insights into understanding the regulatory role of miRNAs in the process of osteogenic differentiation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Bioactive recombinant human BMP-2 was purchased from Novoprotein Scientific, Inc. (Shanghai, China). Anti-Smad1 (catalog no. 1649-1) was purchased from Epitomics, Inc. (Burlingame, CA). Anti-phospho-Smad1/5 (catalog no. 9516) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-Runx2 (S-19) and anti-Smad5 (d-20) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The ALP assay kit, LabAssayTM ALP, was from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). miR-30 family mimics, mimic control (miR-NC), oligonucleotide control (oligo-Ctrl), and miR-30 family inhibitors were synthesized in Genepharma (Shanghai, China).

Cell Culture, Stimulation, and Transfection

MC3T3-E1 cells were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank (Shanghai, China) and were maintained in α modification of Eagle' s minimal essential medium (α-MEM, Invitrogen) containing 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. MC3T3-E1 cells (1 × 105/well) were cultured in 6-well plates overnight and treated with or without 200 ng/ml BMP-2 for various setting time points. For some experiment, mouse bone marrow MSCs were prepared from the bone marrow of femurs and tibias harvested from 2-month-old male C57B/L6 mice (24).

MC3T3-E1 (1 × 105) or mouse bone marrow MSCs (1 × 106) were cultured overnight in 24-well plates and transfected with 40 nm or 80 nm miR-NC, miR-30 family mimics, oligo-Ctrl, or as-miR-30 family (Genepharma) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Three days later, these cells were stimulated with or without 200 ng/ml BMP-2 in completed culture medium for varying periods. In addition, the cells were either harvested for protein and mRNA or fixed with 95% ethanol (v/v) for histochemical examination of ALP activity.

Dual-luciferase Reporter Assay

To determined the common target region of the miR-30 family in Smad1, a segment in the 3′ UTR of the mouse Smad1 cDNA was amplified from genomic DNA using primers 5′-CCG CTC GAG AAG GAT GGA CAA GTC AGA C-3′ and 5′-ATA GTT TAG CGG CCG CCT GCG AAT AAT GAA CAG AG-3′ and cloned between the XhoI and NotI sites of psiCHECK-2 (Promega, Madison, WI). The template psiCHECK-2-Smad1–3′UTR and the primers 5′-GCA AGA ACC CTT TCA CAA AAC ATT GTG ACA TTC T-3′ and 5′AGA ATG TCA CAA TGT TTT GTG AAA GGG TTC TTG C-3′ (psiCHECK-2-Smad1-mut1) or 5′-GAG CAG TTT TTA TGG ACA AAA CAG TAC AGA CAT AG-3′ and 5′-CTA TGT CTG TAC TGT TTT GTC CAT AAA AAC TGC TC-3′ (psiCHECK-2-Smad1-mut2) were used to generate two different seed region mutant (psiCHECK-2-Smad1-mut -3′UTR) constructs by using KOD-Plus (Toyobo Co., Ltd, Biochemical Operations Department, Osaka, Japan). Both of the two target site mutation constructs were cloned by using the template psiCHECK-2-Smad1-mut1 and the primers 5′-GAG CAG TTT TTA TGG ACA AAA CAG TAC AGA CAT AG-3′ and 5′-CTA TGT CTG TAC TGT TTT GTC CAT AAA AAC TGC TC-3′. MC3T3-E1 cells plated in 24-well flat-bottomed plates were transiently cotransfected with 100 ng of each reporter construct (wild-type and mutant Smad1–3′UTR and the psiCHECK-2 vector) and the synthetic miR-30 or control miR-NC using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined 24 h after transfection using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). The Renilla values were normalized to firefly luciferase.

Construction of Smad1 and Runx2 Expression Vectors

Complementary DNAs for the mouse Smad1 and Runx2 genes were obtained by an RT-PCR technique using the PrimeScriptTM PT reagent kit (TaKaRa). Total RNAs prepared from mouse MC3T3-E1 cells were used for the RT-PCR. The primer sequences are shown in supplemental Table 1. PCR products were digested with BglII and NotI (Promega), purified from agarose gels, and subcloned into pCMV-myc (Clontech). Each cDNA was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmid DNA was transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Mutant primers were used to generate a two-seed region mutant for Smad1 (Smad1 + 3′UTR-Mut) and four-seed region mutant for Runx2 (Runx2 + 3′UTR-Mut) construct by using KOD-Plus (Toyobo Co.).

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

MC3T3-E1 cells (1 × 105/ml) were treated in triplicate with the indicated concentrations of BMP-2 in completed culture medium for several days. Total RNA was extracted from the cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScriptTM PT reagent kit (TaKaRa). Amplifications of target genes were performed by real-time quantitative PCR using the cDNA as template, the specific primers and the SYBR® PrimeScript® RT-PCR kit (Takara) on an ABI PRISM 7900 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). PCR amplifications were performed in duplicate at 95 °C for 15 s and subjected to 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 95 °C for 15 s. The primers used were ALP, 5′-CCC TCT CCA AGA CAT ATA ACAC-3′ and 5′-TTG CCC TGA GTG GTG TTG-3′; osteocalcin (OSC), 5′-GGA CCA TCT TTC TGC TCA CT 3′ and 5′-CGG AGT CTG TTC ACT ACC TTA T-3′; Smad1, 5′-CCG CTC GAG AAG GAT GGA CAA GTC AGA C-3′ and 5′-ATA GTT TAG CGG CCG CCT GCG AAT AAT GAA CAG AG-3′; osterix (OSX), 5′-TGG CGT CCT CTC TGC TT-3′ and 5′-TTT CCC CAG GGT TGT TG-3′; bone sialoprotein (BSP), 5′-GTC CAG GGA GGC AGT GAC-3′ and 5′-GAG AGT GTG GAA AGT GTG GAG-3′; and β-actin, 5′-AAC AGT CCG CCT AGA AGC AC-3′ and 5′-CGT TGA CAT CCG TAA AGA CC-3′. The relative levels of miR-30 family member expression to control sno202 were quantified using the TaqMan MicroRNA expression assay (Applied Biosystems). The relative levels of target gene mRNA transcripts to control β-actin were determined by 2-ΔΔCt.

ALP Staining and Activity

MC3T3-E1 cells at 3 × 105 cells/well were cultured overnight in 6-well plates. Three days after transfection, the cells were treated with 200 ng/ml BMP-2 for 7 days. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with 95% ethanol (v/v) and then incubated with a substrate solution from an ALP staining kit (Beyotime® Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) in the dark, according to the manufacturer's protocol. For ALP activity assays, after incubation, the treated cells were washed twice with PBS, and 200 μl of lysis buffer was added to the cell layer and kept on ice for 5 min. The cell lysate was sonicated for 1 min and centrifuged at 1,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. ALP activity was assayed by a spectrophotometric method using a LabAssayTMALP kit. The absorbance at 405 nm of each well was measured with the microplate reader according to the manufacturer's instruction (15).

Alizarin Red Staining

For detection of calcification during differentiation, BMP-2-treated or untreated mouse bone marrow MSCs were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 500 μl of ice-cold 70% ethanol for 10 min. The fixed cells were stained with 500 μl of Alizarin red solution (Sigma).

Western Blot Analysis

Different groups of MC3T3-E1 cells or mouse MSCs (2 × 106/tube) were lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay lysis and extraction buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Individual cell lysates (10 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). After being blocked with SuperBlock T20 PBS blocking buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), the membranes were incubated with rabbit monoclonal antibodies against Smad1 (1:1000), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phospho-Smad1/5 (1:1000), and goat polyclonal antibodies against Smad5 or Runx2 (1:1000), respectively. The bound antibodies were detected with 1:10,000 diluted HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualized using Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by exposure to film and being digitally imaged.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. Data were analyzed by one-way or two-way analysis of variance. Multiple comparison between the groups was performed by using the Bonferroni post hoc test method. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using StatView 5.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and GraphPad Prism 4.0 software.

RESULTS

Dynamic Changes of miR-30 Family Members during BMP-2-induced Osteoblast Differentiation in MC3T3-E1 Cells

It has been indicated that some miR-30 family members are down-regulated during osteogenic differentiation (15). Our previous studies also found that more than one member of miR-30 family significantly decreased in response to osteogenesis-related stimuli (data unpublished), suggesting that the miR-30 family may be important for osteogenic differentiation.

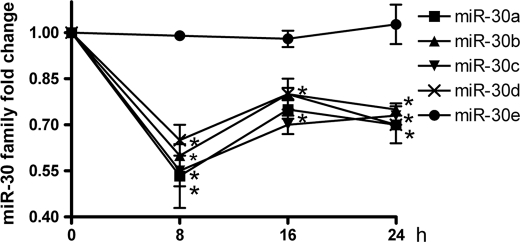

To determine whether miR-30 family members are related to osteogenesis, their kinetics were examined following BMP-2 treatment across a 24-h time course. The miR-30 family has six members: miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, -30e, and miR-384–5p. The expression levels of miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d were down-regulated. They reached their minimum levels at 8 h and then increased slightly (Fig. 1). However, miR-30e did not change. miR-384–5p could not be detected in MC3T3-E1 cells. These data indicate that miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d appear to be involved in the preosteoblast differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells induced by BMP-2.

FIGURE 1.

Dynamic changes of miR-30 family members during BMP-2-induced preosteoblast differentiation. Shown are relative expression levels of miR-30 family members. MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with BMP-2 for 0, 8, 16, and 24 h, and the relative levels of miR-30 family members to sno202 RNA were determined by TaqMan MicroRNA expression assay. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of each group of cells at each time point from three separate experiments. The control at the 0 h time point was designated as 1. *, p < 0.05.

Effects of miR-30 Family Members on Osteoblast Differentiation in MC3T3-E1 Cells

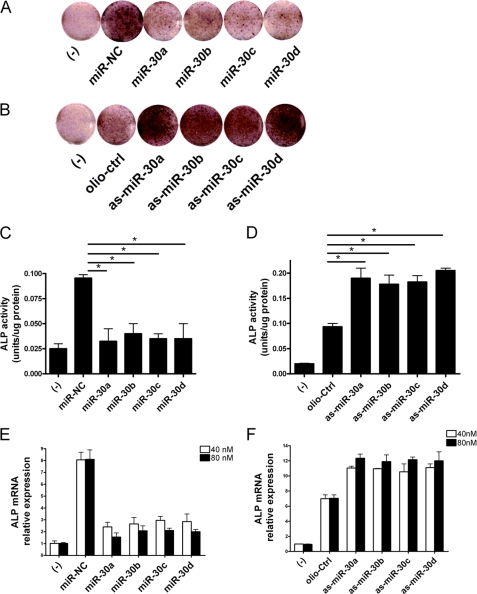

It is well known that ALP activity increases in a time-dependent manner in MC3T3-E1 cells after treatment with BMP-2 (25, 26). To determine whether miR-30 could affect osteoblast differentiation, miR-30 family mimics (miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d) or inhibitors (as-miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d) were transfected into MC3T3-E1 cells, respectively, followed by BMP-2 treatment for 7 days. Then, the ALP activities in the transfected cells were investigated. As shown in Fig. 2, A and C, the ALP activities in the miR-30 overexpressing cells were significantly suppressed compared with those in the miR-NC transfected cells. On the contrary, knockdown of miR-30 expression increased the ALP activities (Fig. 2, B and D). We also observed that miR-30 inhibited ALP mRNA levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2, E and F). These results suggested that miR-30 family members act as negative regulators in osteogenesis induced by BMP-2 stimulation.

FIGURE 2.

miR-30 family members negatively regulate osteogenic differentiation. MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with 40 nm or 80 nm miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, and miR-NC or as-miR-30, -30b, -30c, -30d, and oligo-Ctrl for 72 h and then stimulated with or without 200 ng/ml BMP-2 for another 7 days. The ALP activities and mRNA expression were detected by staining or quantitative RT-PCR, respectively. A, the ALP staining in 40 nm miR-30a-, -30b-, -30c-, and -30d-transfected cells. B, the ALP staining in 40 nm as-miR-30a-, -30b-, -30c, and -30d-transfected cells. C, the ALP activity in 40 nm miR-30a-, -30b-, -30c-, and -30d-transfected cells. D, the ALP activity in 40 nm as-miR-30a-, -30b-, -30c-, and -30d-transfected cells. E, the ALP mRNA expression in 40 nm or 80 nm miR-30a-, -30b-, -30c-, and -30d-transfected cells. F, the ALP mRNA expression in 40 nm or 80 nm as-miR-30a-, -30b-, -30c-, and -30d-transfected cells. The cells transfected with control miR-NC or oligo-Ctrl were designated as negative control. Data are representative images or expressed as mean ± S.E. of each group of cells from three separate experiments, and the values of the control cells were designated as 1. *, p < 0.05.

Smad1 and Runx2 Are Common Targets of the miR-30 Family

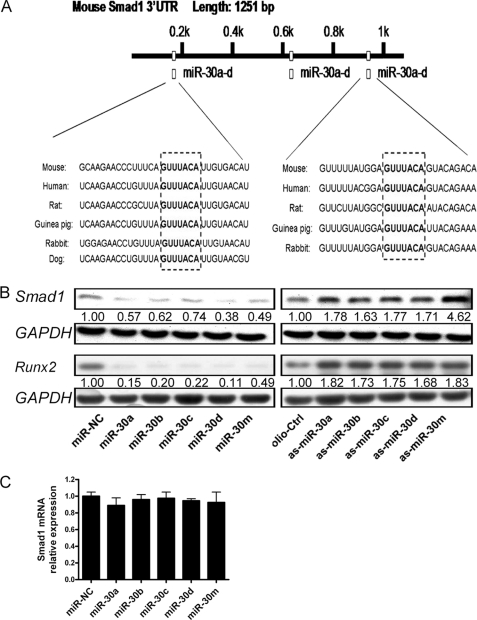

To identify the target genes of miR-30 in osteogenesis, we searched for candidate genes using the miRNA target prediction database TargetScan 5.1. Members of the miR-30 family were predicted to target Smad1 and Runx2, which are key downstream mediators of BMP signaling during bone formation (27–29). There are two and four predicted target sites in the 3′UTR of Smad1 and Runx2, respectively. The sequences of these target sites are highly conserved in different vertebrate species (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. 1). Runx2 has been demonstrated to be a direct target of miR-30 family members (30, 31). However, the function of miR-30 on Smad1 during osteogenic differentiation has not been reported. To test whether Smad1 could be regulated by miR-30, we transfected MC3T3-E1 cells with miR-30 mimics or inhibitors, respectively. The results showed that following transfection, the protein levels of Smad1 decreased when the levels of miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d increased. In contrast, the expression of Smad1 increased after knockdown of miR-30a, -30b, -30c, or -30d. Of note, Smad1 protein level in the as-miR-30a-d mixture (as-miR-30m) cotransfected cells showed nearly a 5-fold increase compared with the control cells, indicating that miR-30 family members are important negative regulators of Smad1 (Fig. 3B). Similar changes in Runx2 protein expression were observed (Fig. 3B). These results provide evidence that the miR-30 family negatively regulates Smad1 and Runx2 expression. Furthermore, quantitative RT-PCR assays demonstrated that Smad1 mRNA did not change in miR-30-overexpressing cells (Fig. 3C), indicating that miR-30 family members regulate Smad1 gene expression on the basis of translational repression rather than mRNA degradation.

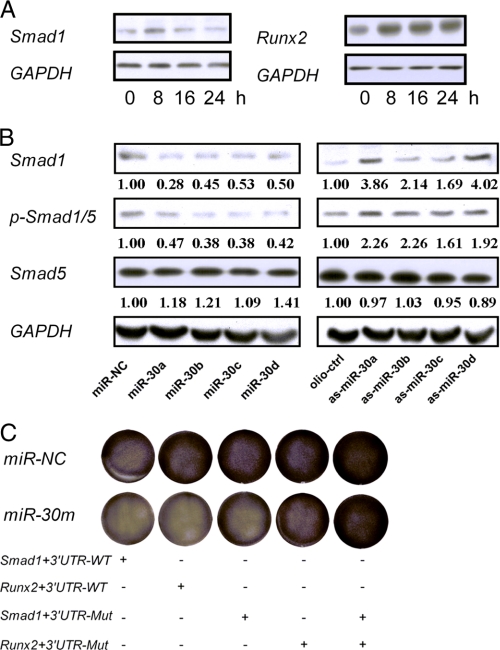

FIGURE 3.

miR-30 family members inhibit Smad1 and Runx2 expression. A, schematic of the miR-30 family putative target sites in mouse Smad1 3′ UTR. B, overexpression or knockdown of miR-30 expression inhibited or enhanced Smad1 and Runx2 expression, respectively. MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with 40 nm miR-NC, miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, a mixture of miR-30a-d (miR-30m) or oligo-Ctrl, as-miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, and a mixture of as-miR-30a-d (as-miR-30m), respectively. Three days later, the relative expression levels of Smad1 and Runx2 to GAPDH were determined by Western blot assays. C, Smad1 mRNA expression. The relative levels of Smad1 mRNA expression to β-actin were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The cells transfected with control miR-NC or oligo-Ctrl were designated as negative control. Data are representative images or expressed as mean ± S.E. of each group of cells from three separate experiments, and the values of the control cells were designated as 1.

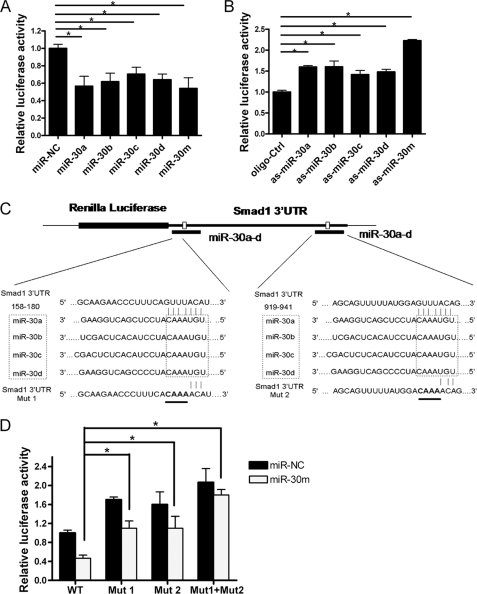

To examine whether miR-30 could directly regulate Smad1 expression, MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter construct containing the wild-type Smad1 3′ UTR, together with the miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, miR-30a-d mixture, miR-NC, as-miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, as-miR-30a-d mixture, or oligo-ctrl, respectively. Clearly, Renilla luciferase activities decreased in miR-30-overexpressing cells, and they increased in miR-30 knockdown cells compared with those in the control cell (Fig. 4, A and B). Then, one or both of the predicted target sites in the Smad1 3′ UTR were mutated (Fig. 4C). As expected, miR-30 significantly inhibited the activities of the wild-type reporter gene, whereas mutation of either seed site partially abolished miR-30-mediated repression of reporter gene activities. Furthermore, mutation of both seed sites completely abolished the repression by miR-30 (Fig. 4D). These data provide strong evidence that miR-30 family members inhibit Smad1 gene expression by directly binding to the two distinct seed sites within its 3′ UTR.

FIGURE 4.

Smad1 is a direct target of the miR-30 family. A and B, Overexpression or knockdown of miR-30 expression inhibited or enhanced the Renilla luciferase activities. MC3T3-E1 cells were cotransfected with 40 nm miR-NC, miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, a mixture of miR-30a-d (miR-30m) or oligo-Ctrl, as-miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, a mixture of as-miR-30a-d, and 100 ng of reporter plasmid containing the wild-type Smad1 3′ UTR. 24 h later, Renilla luciferase values, normalized against firefly luciferase, were presented. C, alignment of alterations in the first (Mut1) and/or the second (Mut2) of the seed sites in the psiCHECK-2-Smad1 reporter gene. The four mutated nucleotides are underlined. D, miR-30 family members target the Smad1 seed sites. MC3T3-E1 cells were cotransfected with the luciferase reporter plasmid carrying the wild-type or mutated sites and miR-NC or miR-30a-d mixture (miR-30m), respectively. Effects of miR-30 on the reporter expression were determined 24 h after transfection. Renilla luciferase values, normalized to firefly luciferase, were presented. The cells transfected with control miR-NC or oligo-Ctrl were designated as negative control. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of each group of cells from three separate experiments, and the values of the control cells were designated as 1. *, p < 0.05. Mut, mutant.

miR-30 Family Members Function through Smad1 and Runx2

To better understand the relationship between miR-30 family members and their targets during osteogenic differentiation, MC3T3-E1 cells stimulated with BMP-2 for 24 h were evaluated for changes of endogenous Smad1 and Runx2 protein expression. The increase of Smad1 and Runx2 protein levels was observed 8 h after stimulation. Then the Smad1 protein decreased slightly (Fig. 5A). The changes of Smad1 and Runx2 protein expression were found to be negatively correlated with that of miR-30 during BMP-2 stimulation (Fig. 1). These results suggest that the early down-regulation of miR-30 expression, immediately after BMP-2 treatment, may facilitate releasing their suppression of Smad1 and Runx2 expression.

FIGURE 5.

miR-30 family members inhibit osteogenesis by suppressing Smad1 and Runx2 expression. A, dynamic changes of Smad1 and Runx2 protein levels in BMP-2-induced MC3T3-E1 cells. The protein samples from Fig. 1 were determined by Western blot assays. B, overexpression or knockdown of miR-30 expression inhibited or enhanced the phospho-Smad1/5 (p-Smad1/5) levels. MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with 40 nm miR-NC, miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d or oligo-Ctrl, as-miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d for 3 days, and then the cells were treated with BMP-2 for 30 min. The expression levels of Smad1, Smad5, and phospho-Smad1/5 to GAPDH were determined by Western blot assays. C, overexpression of Smad1 and Runx2 significantly abolished the inhibitory effects of miR-30 on ALP expression. MC3T3-E1 cells were cotransfected with 40 nm miR-NC, miR-30a-d mixture together with wild-type Smad1 overexpressing plasmid, 3′ UTR-mutant Smad1-overexpressing plasmid, wild-type Runx2-overexpressing plasmid, or 3′ UTR-mutant Runx2-overexpressing plasmid. Then, the cells were treated with BMP-2 for 7 days. The ALP activities were detected by staining.

Upon binding of the BMP ligand to the type I and type II receptor complexes, the activated type I receptor phosphorylates Smad1/5/8, which then assemble into complexes with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus to regulate the expression of genes related to osteoblast differentiation, such as ALP and OSC (32, 33). To study whether the BMP-2-Smad1 pathway could be affected by miR-30, MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with miR-30 (miR-30a, -30b, -30c, or -30d) or control, oligo-Ctrl, or as-miR-30 (as-miR-30a, -30b, -30c, or -30d) and were then treated with BMP-2 for 30 min. Changes in Smad1, Smad5, and phospho-Smad1/5 (p-Smad1/5) protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis. Similar to Smad1, the expression levels of p-Smad1/5 decreased in miR-30-overexpressing cells, whereas they increased in the miR-30 knockdown cells (Fig. 5B).

To confirm the speculation that miR-30 family members function through Smad1 and Runx2, miR-30a-d mixture, together with the wild-type Smad1 overexpressing plasmid, 3′ UTR-mutant Smad1 overexpressing plasmid, wild-type Runx2 overexpressing plasmid, or 3′ UTR-mutant Runx2-overexpressing plasmid, were cotransfected into MC3T3-E1 cells. It demonstrated that transfection with 3′ UTR-mutant Smad1- and Runx2-expressing plasmids was able to eliminate the difference in Smad1 and Runx2 protein levels between miR-30 transfected and control cells (supplemental Fig. 2). When stimulated with BMP-2, the overexpression of Smad1 and Runx2 significantly abolished the inhibitory effects of miR-30 on ALP expression (Fig. 5C). All of these data provide evidence that miR-30 members mediate the inhibition of osteogenesis by targeting Smad1 and Runx2.

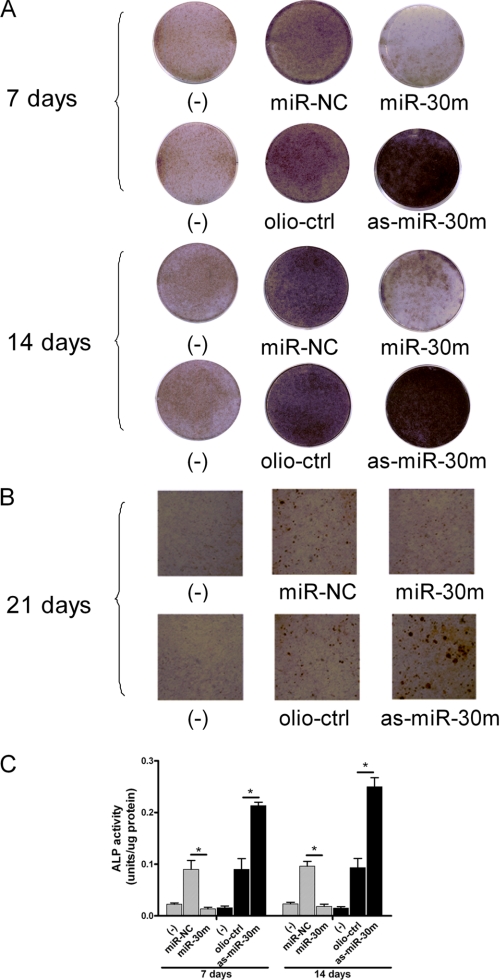

miR-30 Family Members Inhibit Osteogenic Differentiation of Primary Mouse Bone Marrow MSCs

Finally, we addressed the functional activities of miR-30 family members in primary mouse bone marrow MSCs. miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, and miR-30a-d mixture, miR-NC, as-miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, and as-miR-30a-d mixture or oligo-ctrl were transfected into mouse MSCs, respectively. This demonstrated that during the osteogenic differentiation, the miR-30 family member overexpression inhibited the expression levels of ALP, OSC, BSP, and OSX, whereas knockdown of miR-30 family members increased their expression levels (supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, the ALP activities were significantly suppressed or enhanced in the miR-30a-d mixture or as-miR-30a-d mixture-transfected cells, which was compatible with the results of Alizarin red staining (Fig. 6). Both Smad1 and Runx2 were found to be inhibited by miR-30 in MSCs (supplemental Fig. 4). Therefore, these results indicate that miR-30 family members negatively regulate the osteogenic differentiation of mouse bone marrow MSCs.

FIGURE 6.

miR-30 family members inhibit osteogenic differentiation of mouse bone marrow MSCs. Mouse primary bone marrow MSCs were transfected with 40 nm miR-NC, a mixture of miR-30a-d (miR-30m) or oligo-Ctrl, and a mixture of as-miR-30a-d (as-miR-30m) for 2 days, and then the cells were treated with or without BMP-2 (200 ng/ml) for 7, 14, and 21 days. These transfection were repeated every 7 days. A and B, differentiation and mineralization in mouse bone marrow MSCs transfected with miR-30m or as-miR-30m were observed by ALP and Alizarin red staining. C, the ALP activity in miR-30m- or as-miR-30m-transfected mouse bone marrow MSCs. The cells transfected with control miR-NC or oligo-Ctrl were designated as negative control. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of each group of cells from three separate experiments, and the values of the control cells were designated as 1. *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The miR-30 family consists of miR-30a, -30b, -30c, -30d, -30e, and -384–5p. The kinetics of miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d in MC3T3-E1 cells stimulated by BMP-2 are similar (Fig. 1). This suggests that they may play similar roles in osteoblast differentiation. Here, we provide evidence for the concept that miR-30 family members (miR-30a, -30b, -30c, and -30d) regulate osteoblast differentiation and alter the levels of critical molecule of BMP pathways. In contrast, miR-384–5p was undetected, and miR-30e did not change in response to BMP-2 stimulation (Fig. 1). Others also found that not all miR-30 family members changed during osteogenic differentiation induced by BMP-2 in C2C12 cells (15). It is possible that the expression of miR-30 family members is regulated differently.

To investigate the effects of miR-30 family members on BMP-2-induced osteogenic differentiation, we first examined the efficiency and specificity of mimics and inhibitors for miR-30 used in subsequent experiments. Overexpression or knockdown of each member barely affected the expression levels of other members (supplemental Fig. 5). miR-30 family overexpression led to decreased ALP activities, whereas knockdown of them increased mRNA and protein levels of ALP compared with the control cells (Fig. 2, A and D). The same effects were also observed in mouse bone marrow MSCs by overexpressing or inhibiting miR-30 (Fig. 6 and supplemental Fig. 3). These data suggest that miR-30 family members are the negative regulators of osteoblast differentiation induced by BMP-2 in both preosteoblast cell lines and primary cells.

Smad1 is an immediate downstream transducing molecule of the BMP receptor and plays an important role in mediating BMP signaling (34). Osteoblast-specific Smad1 gene knockout mice present with impaired postnatal bone formation (35). So far, several miRNAs have been reported to target Smad1 and regulate its expression in different physiologic conditions. For example, miR-26a regulated osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells by targeting the Smad1 transcription factor (36). miR-199a* was found to adversely regulate early chondrocyte differentiation via directly targeting Smad1 (37). miR-155 targets the 3′ UTR of multiple components of the BMP signaling cascade, including Smad1 in normal and virus-infected cells (38). Our studies also found new miRNAs regulating Smad1 expression in osteoblast differentiation, indicating that Smad1 could be regulated by different miRNAs under different conditions.

In this study, we found two potential binding sites of miR-30 in the Smad1 3′ UTR using bioinformatic analysis and provided direct evidence that Smad1 was the common target of miR-30 family members (Figs. 3 and 4). Mutation of both sites partially eliminated the inhibitory effect of exogenous miR-30 (Fig. 5C). It should be highlighted that in the miR-NC-transfected samples, mutation of either or both sites led to obviously higher Renilla luciferase activities. Considering that mutation of binding sites also abolished the inhibitory function of endogenous miR-30, the result further supported the conclusion that both of these two sites are important for regulation of Smad1 expression.

Besides osteogenesis, it would be interesting to investigate the role of miR-30 in osteoclast differentiation as well, or particularly in chondrocyte differentiation, as Smad1 signaling is also involved in chondrogenesis (37). Although we have found that miR-30 family members are associated with osteogenic differentiation of mouse bone marrow MSCs (Fig. 6 and supplemental Fig. 3), it remains to be determined whether they are differentially expressed in cartilage, bone, or both. Future in vivo experiments in mouse models are necessary to address miR-30 function in depth. In addition to BMP pathways, Smad1 is also a mediator of TGF-β pathways in several non-endothelial cell lineages (39), so it is possible that miR-30 family members may be involved in regulating TGF-β signaling pathways.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the members of miR-30 family, in response to BMP-2, act as the negative regulators of early osteoblast differentiation through their suppression of Smad1 and Runx2 transcription factors. This study provides new insights into BMP/Smad signaling regulation in osteoblast differentiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiuli Zhang from the Oral Bioengineering Laboratory, Shanghai Research Institute of Stomatology, Ninth People's Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, for technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China Grants 30670555 and 81170988, by Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project S30206 and by Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality Grant 11ZR1420200.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–5 and Table 1.

- miRNA

- microRNA

- UTR

- untranslated region

- ALP

- alkaline phosphatase

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cell.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lee R. C., Feinbaum R. L., Ambros V. (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75, 843–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. (2001) Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294, 853–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee R. C., Ambros V. (2001) An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294, 862–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ambros V. (2003) MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms. Growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell 113, 673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nelson P., Kiriakidou M., Sharma A., Maniataki E., Mourelatos Z. (2003) The microRNA world. Small is mighty. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ambros V. (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bartel D. P. (2004) MicroRNAs. Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sato M. M., Nashimoto M., Katagiri T., Yawaka Y., Tamura M. (2009) Bone morphogenetic protein-2 down-regulates miR-206 expression by blocking its maturation process. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 383, 125–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang J., Zhao L., Xing L., Chen D. (2010) MicroRNA-204 regulates Runx2 protein expression and mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells 28, 357–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schaap-Oziemlak A. M., Raymakers R. A., Bergevoet S. M., Gilissen C., Jansen B. J., Adema G. J., Kögler G., le Sage C., Agami R., van der Reijden B. A., Jansen J. H. (2010) MicroRNA hsa-miR-135b regulates mineralization in osteogenic differentiation of human unrestricted somatic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 19, 877–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mizuno Y., Yagi K., Tokuzawa Y., Kanesaki-Yatsuka Y., Suda T., Katagiri T., Fukuda T., Maruyama M., Okuda A., Amemiya T., Kondoh Y., Tashiro H., Okazaki Y. (2008) miR-125b inhibits osteoblastic differentiation by down-regulation of cell proliferation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 368, 267–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li H., Xie H., Liu W., Hu R., Huang B., Tan Y. F., Xu K., Sheng Z. F., Zhou H. D., Wu X. P., Luo X. H. (2009) A novel microRNA targeting HDAC5 regulates osteoblast differentiation in mice and contributes to primary osteoporosis in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 3666–3677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Itoh T., Takeda S., Akao Y. (2010) MicroRNA-208 modulates BMP-2-stimulated mouse preosteoblast differentiation by directly targeting V-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27745–27752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Itoh T., Nozawa Y., Akao Y. (2009) MicroRNA-141 and -200a are involved in bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced mouse pre-osteoblast differentiation by targeting distal-less homeobox 5. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19272–19279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li Z., Hassan M. Q., Volinia S., van Wijnen A. J., Stein J. L., Croce C. M., Lian J. B., Stein G. S. (2008) A microRNA signature for a BMP2-induced osteoblast lineage commitment program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13906–13911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li Z., Hassan M. Q., Jafferji M., Aqeilan R. I., Garzon R., Croce C. M., van Wijnen A. J., Stein J. L., Stein G. S., Lian J. B. (2009) Biological functions of miR-29b contribute to positive regulation of osteoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15676–15684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sugatani T., Hruska K. A. (2007) MicroRNA-223 is a key factor in osteoclast differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 101, 996–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. O'Connell R. M., Taganov K. D., Boldin M. P., Cheng G., Baltimore D. (2007) MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1604–1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boyan B. D., Weesner T. C., Lohmann C. H., Andreacchio D., Carnes D. L., Dean D. D. (2000) Porcine fetal enamel matrix derivative enhances bone formation induced by demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft in vivo. J. Periodontol. 71, 1278–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miron R. J., Oates C. J., Molenberg A., Dard M., Hamilton D. W. (2010) The effect of enamel matrix proteins on the spreading, proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts cultured on titanium surfaces. Biomaterials 31, 449–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iwata T., Morotome Y., Tanabe T., Fukae M., Ishikawa I., Oida S. (2002) Noggin blocks osteoinductive activity of porcine enamel extracts. J. Dent. Res. 81, 387–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Suzuki S., Nagano T., Yamakoshi Y., Gomi K., Arai T., Fukae M., Katagiri T., Oida S. (2005) Enamel matrix derivative gel stimulates signal transduction of BMP and TGF-{β}. J. Dent. Res. 84, 510–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goda S., Inoue H., Kaneshita Y., Nagano Y., Ikeo T., Ikeo Y. T., Iida J., Domae N. (2008) Emdogain stimulates matrix degradation by osteoblasts. J. Dent. Res. 87, 782–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edgar C. M., Chakravarthy V., Barnes G., Kakar S., Gerstenfeld L. C., Einhorn T. A. (2007) Autogenous regulation of a network of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) mediates the osteogenic differentiation in murine marrow stromal cells. Bone 40, 1389–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamazaki M., Fukushima H., Shin M., Katagiri T., Doi T., Takahashi T., Jimi E. (2009) Tumor necrosis factor α represses bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling by interfering with the DNA binding of Smads through the activation of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35987–35995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thaler R., Spitzer S., Rumpler M., Fratzl-Zelman N., Klaushofer K., Paschalis E. P., Varga F. (2010) Differential effects of homocysteine and β aminopropionitrile on preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Bone 46, 703–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen D., Zhao M., Mundy G. R. (2004) Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors 22, 233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Banerjee C., McCabe L. R., Choi J. Y., Hiebert S. W., Stein J. L., Stein G. S., Lian J. B. (1997) Runt homology domain proteins in osteoblast differentiation. AML3/CBFA1 is a major component of a bone-specific complex. J. Cell. Biochem. 66, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mukai T., Otsuka F., Otani H., Yamashita M., Takasugi K., Inagaki K., Yamamura M., Makino H. (2007) TNF-α inhibits BMP-induced osteoblast differentiation through activating SAPK/JNK signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 356, 1004–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zaragosi L. E., Wdziekonski B., Brigand K. L., Villageois P., Mari B., Waldmann R., Dani C., Barbry P. (2011) Small RNA sequencing reveals miR-642a-3p as a novel adipocyte-specific microRNA and miR-30 as a key regulator of human adipogenesis. Genome Biol. 12, R64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Y., Xie R. L., Croce C. M., Stein J. L., Lian J. B., van Wijnen A. J., Stein G. S. (2011) A program of microRNAs controls osteogenic lineage progression by targeting transcription factor Runx2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9863–9868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamamoto N., Akiyama S., Katagiri T., Namiki M., Kurokawa T., Suda T. (1997) Smad1 and smad5 act downstream of intracellular signalings of BMP-2 that inhibits myogenic differentiation and induces osteoblast differentiation in C2C12 myoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238, 574–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nishimura R., Hata K., Harris S. E., Ikeda F., Yoneda T. (2002) Core-binding factor α 1 (Cbfa1) induces osteoblastic differentiation of C2C12 cells without interactions with Smad1 and Smad5. Bone 31, 303–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoodless P. A., Haerry T., Abdollah S., Stapleton M., O'Connor M. B., Attisano L., Wrana J. L. (1996) MADR1, a MAD-related protein that functions in BMP2 signaling pathways. Cell 85, 489–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang M., Jin H., Tang D., Huang S., Zuscik M. J., Chen D. (2011) Smad1 plays an essential role in bone development and postnatal bone formation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 19, 751–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Luzi E., Marini F., Sala S. C., Tognarini I., Galli G., Brandi M. L. (2008) Osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells is modulated by the miR-26a targeting of the SMAD1 transcription factor. J. Bone Miner. Res. 23, 287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lin E. A., Kong L., Bai X. H., Luan Y., Liu C. J. (2009) miR-199a, a bone morphogenic protein 2-responsive MicroRNA, regulates chondrogenesis via direct targeting to Smad1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11326–11335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yin Q., Wang X., Fewell C., Cameron J., Zhu H., Baddoo M., Lin Z., Flemington E. K. (2010) MicroRNA miR-155 inhibits bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling and BMP-mediated Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. J. Virol. 84, 6318–6327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wrighton K. H., Lin X., Yu P. B., Feng X. H. (2009) Transforming Growth Factor {β} can stimulate Smad1 phosphorylation independently of bone morphogenic protein receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9755–9763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.