Background: CPS-6 (EndoG) degrades chromosomal DNA during apoptosis.

Results: The crystal structure of C. elegans CPS-6 was determined, and the DNA binding and cleavage mechanisms by CPS-6 were revealed.

Conclusion: The DNase activity of CPS-6 is positively correlated with its pro-cell death activity.

Significance: This study improves our general understanding of DNA hydrolysis by ββα-metal finger nucleases and the process of apoptotic DNA fragmentation.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Crystal Structure, DNA Enzymes, DNA-Protein Interaction, DNase, Nucleic Acid Enzymology

Abstract

Endonuclease G (EndoG) is a mitochondrial protein that traverses to the nucleus and participates in chromosomal DNA degradation during apoptosis in yeast, worms, flies, and mammals. However, it remains unclear how EndoG binds and digests DNA. Here we show that the Caenorhabditis elegans CPS-6, a homolog of EndoG, is a homodimeric Mg2+-dependent nuclease, binding preferentially to G-tract DNA in the optimum low salt buffer at pH 7. The crystal structure of CPS-6 was determined at 1.8 Å resolution, revealing a mixed αβ topology with the two ββα-metal finger nuclease motifs located distantly at the two sides of the dimeric enzyme. A structural model of the CPS-6-DNA complex suggested a positively charged DNA-binding groove near the Mg2+-bound active site. Mutations of four aromatic and basic residues: Phe122, Arg146, Arg156, and Phe166, in the protein-DNA interface significantly reduced the DNA binding and cleavage activity of CPS-6, confirming that these residues are critical for CPS-6-DNA interactions. In vivo transformation rescue experiments further showed that the reduced DNase activity of CPS-6 mutants was positively correlated with its diminished cell killing activity in C. elegans. Taken together, these biochemical, structural, mutagenesis, and in vivo data reveal a molecular basis of how CPS-6 binds and hydrolyzes DNA to promote cell death.

Introduction

Endonuclease G (EndoG)2 was first identified as a mitochondrial DNase that prefers to cleave phosphordiester bonds of DNA at (dG)n tracts in yeasts and mammals (1–3). It was later recognized as one of the apoptotic nucleases that participate in chromosome fragmentation during apoptosis in mice and worms (4, 5). Apoptotic nucleases have attracted attention because their inactivation may produce undigested DNA that lead to autoimmune disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis (6, 7). In the search of apoptotic nucleases, CAD/DFF40 was the first one identified in mammals (8, 9). EndoG was subsequently discovered as an apoptotic DNase released from mitochondria, mediating residual DNA fragmentation in CAD/DFF40-decificient mice (5). An independent genetic screen for cell death effectors also identified CPS-6, an EndoG homolog, to be a nuclease important for apoptotic chromosome fragmentation in Caenorhabditis elegans (4). CPS-6 in C. elegans and EndoG in mouse and yeast were shown to be compartmented in the mitochondrial intermembrane space so that it does not affect nuclear genomic DNA in nonapoptotic cells; in response to apoptotic signals, it is released and translocated to the nucleus to digest chromosomal DNA (10).

Biochemical and genetic evidence further showed that C. elegans CPS-6 associates and cooperates with WAH-1, a C. elegans homolog of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), and CRN-1 (cell death-related nucleases) to promote DNA degradation during apoptosis (11, 12). Mammalian EndoG also interacts with AIF and FEN-1 (a CRN-1 homolog) (13). Therefore, the roles of CPS-6 and EndoG in apoptotic chromosome fragmentation are likely conserved. Indeed, mouse EndoG can rescue the cell death defects of the cps-6 mutant in C. elegans (4). Apart from CPS-6, a number of nucleases have been identified that are involved in chromosome fragmentation during apoptosis in C. elegans, including NUC-1, DCR-1, and cell death-related nucleases (CRN-1 to CRN-7) (14–17). CPS-6 interacts not only with CRN-1 and WAH-1 but also with CRN-3, CRN-4, CRN-5, and CYP-13, and these proteins, likely in the form of a multi-nuclease complex, work together to promote apoptotic DNA fragmentation (14). Inactivation of cps-6 (the gene encoding CPS-6) resulted in the accumulation of TUNEL-positive cells and delayed appearance of embryonic cell corpses during development, suggesting that CPS-6 is required for normal apoptotic DNA degradation (14). Knock-out of the EndoG gene in mice did not cause significant phenotypes either in embryogenesis or in apoptosis, possibly because of the presence of redundant apoptotic nucleases and various apoptotic DNA degradation pathways during apoptosis (18, 19).

Investigation of the cellular functions of EndoG suggests that this nuclease not only has a pro-death role in apoptosis but also plays a pro-life role in mitochondrial DNA replication and recombination (20, 21). The conflicting life versus death role of EndoG was clarified in budding yeast in which EndoG functions as a potent cell death inducer only under high respiration conditions in a caspase- and AIF-independent mechanism, whereas EndoG promotes cell viability under high cell division conditions (22). Thus yeast EndoG can either act as a crucial but uncharacterized molecule in mitochondria for cell proliferation or be switched to a death executioner, digesting chromosomal DNA in the nucleus during apoptosis in a caspase-independent pathway.

Mammalian, Drosophila, C. elegans, and yeast CPS-6/EndoG share sequence homology with Serratia nuclease, which contains a conserved DRGH sequence in the ββα-metal finger motif that has been identified in a number of other bacterial nonspecific nucleases (Fig. 1) (23, 24). Yeast and mammalian EndoGs are Mg2+-dependent homodimeric proteins with a preference for single-stranded RNA and DNA substrates (3). Drosophila EndoG particularly has a nuclear inhibitor EndoGI that likely protects the cell against low levels of EndoG that leaks out from mitochondria (25). The crystal structure of Drosophila EndoG in complex with its inhibitor EndoGI has been reported, revealing how the monomeric EndoGI inhibits the activity of the dimeric EndoG by blocking its active site and oligonucleotide-binding groove (26).

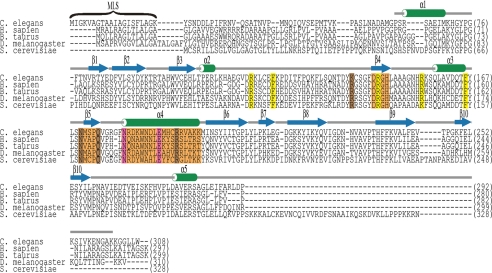

FIGURE 1.

Sequence alignment of CPS-6/EndoG. Sequences of CPS-6/EndoG from C. elegans, Homo sapiens, Bos taurus, D. melanogaster, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are aligned and listed. CPS-6 shares high sequence identities of 50, 49, 55, and 39% with human, bovine, fruit fly, and yeast EndoG, respectively. The amino acid residues found in H. sapiens, B. taurus, and D. melanogaster important for metal ion coordination and DNA binding are colored in pink and brown, respectively (22, 23, 26, 30). The ββα-metal finger motif (β4-β5-α4) is marked in orange, and the conserved 145DRGH148 sequence is located in β4. The residues that are likely involved in DNA binding and that were subjected to site-directed mutagenesis in this study are colored in yellow. The secondary structures derived from the crystal structure of CPS-6 are depicted as green cylinders for α-helices and blue arrows for β-strands. MLS, mitochondrial localization sequence.

Although the pro-death role of CPS-6/EndoG has been studied most extensively in C. elegans, the biochemical and structural information for CPS-6 remains unknown. To understand the intriguing life versus death role of CPS-6, we employed a range of biochemical assays in combination with x-ray crystallography to determine the crystal structure of CPS-6 bound with a Mg2+ cofactor in the active site at a high resolution of 1.8 Å. This structural information led to the identification of the critical DNA binding residues, which were verified through site-directed mutagenesis and several different in vitro assays and provided invaluable insights for in vivo functional assays. In particular, reduced DNase activities of the CPS-6 mutants positively correlated with their decreased pro-apoptotic activities in C. elegans. This study thus provides a molecular basis for the DNA binding and hydrolysis by CPS-6 during apoptosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Protein Expression, and Purification

The genes encoding CPS-6 (CPS-6 residues 63–305) and WAH-1 (WAH-1 residues 214–700) were amplified by PCR using Taq DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The primers used for CPS-6 PCR were 5′-GATGCAGGATCCCCATCTCGTTCGGCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAATCAAAGCTTTCATCCTCCCTTCTTTGC-3′ (reverse). The primers used for cAIF PCR were 5′-GCGGGATCCTCCGAACAACAATCGATGAAGCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCGCTGCAGCTAAGCACTCTTCGCATC-3′ (reverse). The PCR-amplified genes were cloned into the BamHI/HindIII or BamHI/PstI site, respectively, of the expression vector pQE30 (Qiagen) to generate the His-tagged fusion constructs. All of the CPS-6 point mutants were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kits (Stratagene).

Single colonies of the Escherichia coli strain M15 transformed with pQE30-CPS-6-(63–305) or pQE30-WAH-1-(214–700) plasmids were inoculated into 10 ml of LB medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and grown at 37 °C overnight. The overnight cultures were grown to an A600 of 0.6 and then induced with 0.8 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 18 °C for 20 h. The harvested cells were disrupted by a microfluidizer in a buffer containing 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, and 5% glycerol. The crude cell extract was passed through a TALON® metal affinity resin column (BD Biosciences) followed by a gel filtration chromatography column (Superdex 200; GE Healthcare) in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 500 mm NaCl, and 2.5 mm DTT. Purified protein samples were concentrated to suitable concentrations and stored at −80 °C until use.

Nuclease Activity Assays

For the DNase activity assays shown in Fig. 2C, a PCR-amplified 1.6-kb linear double-stranded DNA fragment (40 ng) was incubated with purified protein (0–0.1 μm) in a buffer containing 50 mm MES (pH 6.0), 25 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm DTT. To investigate the pH effects on the DNase activity, as shown in Fig. 2D, pET28 plasmid DNA (25 ng) was incubated with 2 μm purified protein in 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT, and various buffers of 10 mm of sodium acetate trihydrate (pH 4), tri-sodium citrate dehydrate (pH 5), sodium cacodylate (pH 6), sodium HEPES (pH 7), Tris-HCl (pH 8), CAPSO (pH 9), and CAPS (pH 10 and 11). For examine salt effects on the DNase activity, as shown in Fig. 2E, pET28 plasmid DNA (25 ng) was incubated with 2 μm purified protein in a reaction buffer containing 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.0), 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT, and various concentrations of NaCl (25–500 mm). For the DNase activity assays shown in Fig. 3A, purified wild-type CPS-6 (0.03 to 2 μm) was incubated with pET28 plasmid DNA (25 ng) in the optimal CPS-6 buffer (10 mm HEPES (pH 7.0), 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm DTT). For the DNase activity assays shown in Fig. 3B, purified wild-type CPS-6 (0.06–2 μm) was incubated with 60 nm 48-mer ssDNA (5′-ACGCTGCCGAATTCTGGCGTTAGGAGATACCGATAAGCTTCGGCTTAA) or dsDNA (above 48-mer ssDNA annealed with its complementary sequence), both of which were 32P-labeled at the 5′-end in the optimal CPS-6 buffer. For the DNase activity assays shown in Fig. 3C, purified wild-type protein (0.25–1 μm) was incubated with either 10 nm 11-mer ssDNA (5′-AACCTTACAAC-3′) or ssRNA (5′-AACCUUACAAC-3′), both of which were labeled at the 5′-end with 32P, in the optimal CPS-6 buffer. For the DNase activity assays shown in Fig. 5C, purified wild-type and mutated CPS-6 (2 μm) were incubated with pET28 plasmid DNA (25 ng) in the optimal CPS-6 buffer. All of the reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The digested DNA samples were resolved on a 1% agarose gel (Figs. 2, C–E, and 3A), stained by ethidium bromide, and detected with a charge-coupled device camera at UV transillumination. In Fig. 3B, the digested DNA samples were resolved in a 20% native polyacrylamide gel and run in 1× TBE (90 mm Tris-borate, 2.0 mm EDTA). In Fig. 3C, the digested DNA or RNA samples were resolved in a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (8 m urea) run in 1× TBE (90 mm Tris-borate, 2.0 mm EDTA). The gel was subsequently exposed to a phosphorimaging plate (Fujifilm) and visualized using an FLA-5000 (Fujifilm) imaging system.

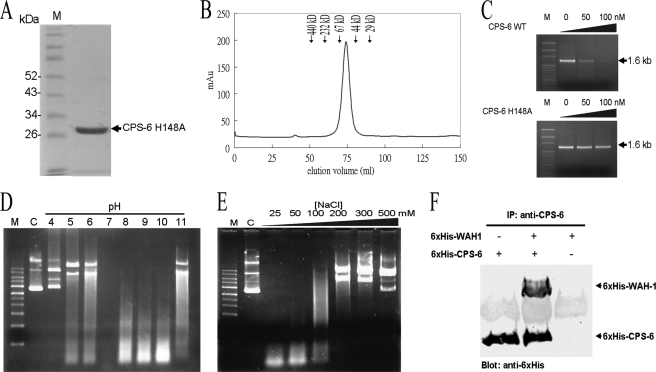

FIGURE 2.

The recombinant CPS-6 is a functional homodimeric nuclease. A, the purity of the recombinant CPS-6 (63–305) H148A mutant was assayed by 12% SDS-PAGE. B, size exclusion chromatographic profile of CPS-6 H148A mutant showing that the protein was eluted at 74 ml, indicating a dimeric conformation. The protein markers used here are ferritin (440 kDa), catalase (232 kDa), bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), ovalbumin (44 kDa), and carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa). C, wild-type CPS-6 digests 1.6-kb linear DNA fragments (upper panel) in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas H148A has no nuclease activity (lower panel). Lane M is a DNA marker. D, CPS-6 digests plasmid DNA most efficiently at pH 7. pET28 plasmid DNA (25 ng) was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 2 μm CPS-6 in reaction buffer containing 25 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm DTT with pH values ranging from 4 to 11. Lane M is a DNA marker, and lane C is a control in the absence of CPS-6. E, CPS-6 digests plasmid DNA more efficiently at low salt concentrations (25–100 mm NaCl). F, the immunoprecipitation experiment shows that the His6-tagged CPS-6 (H148A mutant) interacts directly with the His-tagged WAH-1.

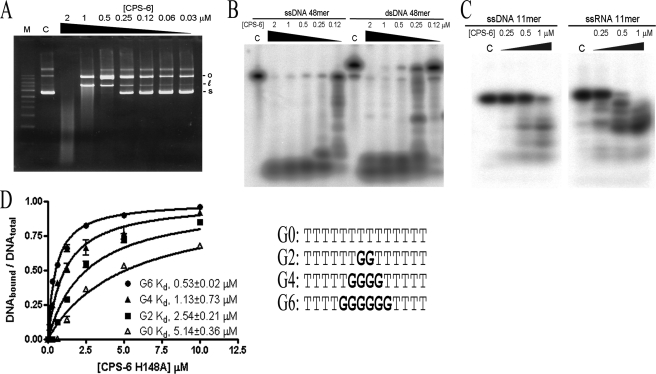

FIGURE 3.

CPS-6 digests both DNA and RNA with a preference for G-track DNA. A, CPS-6 digests pET28 plasmid DNA (25 ng) in a concentration-dependent manner (0.03–2 μm). Lane M is a DNA marker. B, CPS-6 digests both 5′-end 32P-labeled single-stranded DNA (48 nucleotides) and double-stranded DNA (48 bp). C, CPS-6 digests 11-mer ssRNA (5′-end 32P-labeled 5′-AACCUUACAAC-3′) and 11-mer ssDNA (5′-end 32P-labeled 5′-AACCTTACAAC-3′) substrate. All of the reactions in A–C were carried out in the buffer of 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm DTT for 1 h at 37 °C. Lanes C are controls in the absence of CPS-6. D, the binding constants between CPS-6 H148A mutant and the 14-nucleotide 5′-end 32P-labeled ssDNA containing different lengths of poly(dG) were measured by nitrocellulose filter binding assays. The dissociation constants between CPS-6 H148A and ssDNA containing zero (open triangle), two (circle), four (triangle), and six G (closed rectangle) are 5.14 ± 0.36, 2.54 ± 0.21, 1.13 ± 0.73, and 0.53 ± 0.02 μm, respectively. The error bars are generated from three independent experiments.

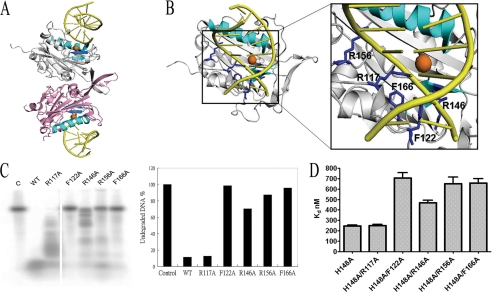

FIGURE 5.

Identification of the residues involved in DNA binding in CPS-6. A, side view of a model of CPS-6 homodimer bound with two DNA molecules. The ββα-metal motif is colored in cyan, and the Mg2+ ion is in orange. The dsDNA molecules are colored in yellow. B, the top view of CPS-6-DNA complex model suggests that several basic and aromatic amino acid residues (in blue) are located closely to the DNA backbones, likely involved in protein-DNA interactions, including Arg117, Phe122, Arg146, Arg156, and Phe166. C, the DNA digestion assays show that a mutation at Phe122, Arg146, Arg156, and Phe166, but not at Arg117, greatly reduced the DNase activity of CPS-6, suggesting that these residues are involved in DNA binding and/or digestion. The integrated density values (shown as percentages, as normalized using the control DNA as 100%) for the undigested full-length 5′-end 32P-labeled ssDNA used in this study are summarized as a histogram. D, the dissociation constants between CPS-6 mutants and DNA (5′-end 32P-labeled 48-nt ssDNA) were measured by filter binding assays. The dissociation constants are shown in the histogram: 245 ± 18 nm for H148A, 249 ± 20 for H148A/R117A, 707 ± 88 nm for H148A/F122A, 468 ± 42 nm for H148A/R146A, 652 ± 111 nm for H148A/R156A, and 658 ± 74 nm for H148A/F166A.

Filter Binding Assay

Single-stranded DNA substrates for the filter binding assay were 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase. The 32P-labeled DNA (14 fmol) were incubated with the serial dilution of protein samples in the binding buffer containing 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm DTT, and 2 mm EDTA for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction mixtures were then passed through the filter binding assay apparatus (Bio-Dot SF microfiltration apparatus; Bio-Rad). After extensive washing, the CPS-6-DNA complex-bound nitrocellulose membrane and free DNA-bound nylon membrane were air-dried and exposed to a phosphorimaging plate. The intensities of CPS-6-DNA complex and free DNA were quantified by the program AlphaImager IS-2200 (Alpha Innotech). The binding percentages were calculated and normalized. The apparent Kd values were estimated by one-site binding curve fitting using GraphPad Prism 4.

Immunoprecipitation

The His-tagged CPS-6 (22–308) H148A mutant (1 μg) was mixed with 1 μg of His-tagged WAH-1 (214–700) and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C in buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 300 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 5 mm DTT. This reaction was followed by the addition of anti-CPS-6 (polyclonal rabbit; 1:100 dilution) and continued to be agitated at 4 °C for 2 h. Protein G beads (Amersham Biosciences) were premixed with 1 μg of bovine serum albumin followed by washing three times with reaction buffer and then added to the reaction mixture, followed by incubation for 2 h at 4 °C. The protein beads were then centrifuged, and the supernatant was removed. After washing three times with reaction buffer, the beads were loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE followed by the detection of immunoblotting using anti-His antibodies (monoclonal mouse).

In Vivo Cell Death Assay

Pdpy-30CPS-6 construct was used for in vivo expression (4). To construct Pdpy-30CPS-6(H148A), Pdpy-30CPS-6(R146A), and Pdpy-30CPS-6(F166A), HindIII-PstI fragments, including the corresponding mutations, were excised from pQE30-CPS-6(H148A), pQE30-CPS-6(R146A), and pQE30-CPS-6(F166A), respectively, and subcloned into the Pdpy-30CPS-6 construct by replacing the wild-type fragment via its HindIII and PstI sites.

C. elegans strains were maintained using standard procedures (27). The CPS-6 expression constructs (at 20 μg/ml) were injected into cps-6(sm116) animals as previously described (28), using the pTG96 plasmid (at 20 μg/ml) as a coinjection marker, which directs GFP expression in all cells in most developmental stages (29). The numbers of cell corpses in living GFP-positive transgenic embryos were determined using Nomarski optics as described previously (11).

Crystallization and Crystal Structural Determination

Crystals of CPS-6 were grown by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 4 °C. The crystallization drop was made by mixing 0.5 μl of protein solution and 0.5 μl of reservoir solution. The CPS-6 H148A mutant (10 mg/ml in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 500 mm NaCl and 2.5 mm DTT) was crystallized using a reservoir solution containing 6% Tacsimate, 0.1 m MES (pH 6.0), and 25% PEG 4000. The diffraction data were collected at the BL44XU Beamline at SPring-8 (Japan) and were processed and scaled by HKL2000. The crystal structure was solved by the molecular replacement method using the crystal structure of Drosophila melanogaster EndoG (Protein Data Bank code 3ISM, chains A and B) as the search model by program MOLREP of CCP4. The models were modified by Coot and refined by Phenix. The diffraction and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1. The structural coordinates and diffraction structure factors have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank with the Protein Data Bank code 3S5B for CPS-6 H148A mutant.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic statistics of CPS-6

| Data collection and processing | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0 |

| Space group | P21 |

| Cell dimensions (a, b, c/ β) (Å/degree) | 69.2, 45.4, 80.3/ 104.2 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.8-37.6 (1.80-1.83)a |

| Observed/unique reflections | 130,358/44,074 |

| Data redundancy | 3.0 (2.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.9 (100) |

| Rsym (%) | 8.5 (34.8) |

| I/σ(I) | 20.1 (4.7) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution range | 1.8–37.6 |

| Reflections (work/test) | 41,201/1,876 |

| Rfactor/Rfree (%) | 16.6/21.0 |

| Number of non-hydrogen atoms: Protein/metal ions/water molecules | 3,836/2/430 |

| Model quality | |

| Root mean square deviation in bond length (Å)/bond angle (°) | 0.007/1.043 |

| Average B-factor: protein/metal/solvent (Å2) | 12.6/14.1/25.5 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favored | 98 |

| Additionally allowed | 0.5 |

| Generally allowed | 1.5 |

| Disallowed | 0 |

a The values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

RESULTS

Recombinant CPS-6 Is Functional Homodimeric Endonuclease

To investigate the structure and biochemical properties of CPS-6, the recombinant wild-type His6-tagged CPS-6 (residues 63–305) was expressed in E. coli. The N-terminal residues (1–62) and the C-terminal residues (306–308) were not included for expression. However, the expression level of the wild-type CPS-6 was low because of its toxic DNase activity in E. coli. Therefore, the putative general base residue His148 was mutated to generate a CPS-6 mutant (H148A), which can be expressed in a large amount. The N-terminal sequence (residues 1–62) was removed because it was unstable and degraded with time. The wild-type and mutated CPS-6 (residues 63–305) proteins were expressed and purified by chromatographic methods using a Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column, followed by a Superdex 200 gel filtration column. They were purified to homogeneity as confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). The recombinant CPS-6 appeared as a dimeric protein as determined by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column (Fig. 2B), with an apparent native molecular mass of about 48 kDa (calculated molecular mass of CPS-6 monomer, 28.5 kDa).

The nuclease activity of purified wild-type CPS-6 was analyzed by incubation of CPS-6 with a linear 1.6-kb DNA fragment in a buffer containing 25 mm NaCl and 5 mm MgCl2 for one h. A relatively rapid degradation of DNA was observed with wild-type CPS-6, but not with the H148A mutant, as a function of increasing protein concentration (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, CPS-6 (0–1 μm) was incubated with DNA in the presence and absence of EDTA. CPS-6 had significantly reduced DNase activity in the presence of EDTA, suggesting that divalent metal ions are required for the enzyme activity of CPS-6 (supplemental Fig. S1). The optimal conditions for the nuclease activity of CPS-6 were further characterized over a wide range of pH values and salt concentrations. CPS-6 digested plasmid DNA most efficiently at neutral pH and at low salt concentrations (25–100 mm NaCl) in the presence of 2 mm MgCl2 (Fig. 2, D and E). A relatively more efficient nuclease activity for CPS-6 was found at pH values ranging from 7 to 10 rather than that of 4 to 6 in the presence of 100 mm NaCl (Fig. 2D). Given the pKa value of ∼6 for His148, acidic conditions might have caused its protonation and hence the loss of the general base function. Moreover, high salt buffers might interfere with the interactions between the positively charged CPS-6 and negatively charged DNA.

The recombinant CPS-6(H148A) mutant was further tested for its ability to interact with WAH-1 by immunoprecipitation. Anti-CPS-6 antibody was used to pull down the CPS-6/WAH-1 complex, which was detected by Western blotting using anti-His antibodies. This experiment showed that the purified recombinant His-tagged CPS-6 interacted directly with the purified His-tagged WAH-1 (Fig. 2F). Taken together, these results show that the recombinant CPS-6 was a fully functional protein, capable not only of DNA digestion but also of interaction with WAH-1.

CPS-6 Digests RNA and DNA with Preference for Binding a G-track DNA

To determine the substrate preference for CPS-6, pET28 plasmid DNA (25 ng) was used as the substrate in a concentration course experiment under the reaction conditions of 100 mm NaCl and 2 mm MgCl2 at pH 7. CPS-6 cleaved plasmid DNA in a concentration-dependent manner, steadily converting the supercoiled DNA into the open circular and linear forms, when the concentration of CPS-6 was increased from 0.03 to 2 μm (Fig. 3A). A significant amount of DNA digestion, visible as a broad smear, was observed when the protein concentration was increased to 2 μm (Fig. 3A). This result confirms that CPS-6 has endonuclease activity.

Linear ssDNA and dsDNA substrates (48-mers) were next used for digestion experiments with wild-type CPS-6 (residues 63–305). We observed that ssDNA was cleaved a bit more efficiently than dsDNA (Fig. 3B). A comparison between 11-mer ssDNA and ssRNA showed that wild-type CPS-6 (residues 63–305) digested 11-mer ssRNA more efficiently than 11-mer ssDNA (Fig. 3C). These results show that CPS-6 digests both DNA and RNA and prefers single-stranded nucleic acid substrates slightly over double-stranded ones, in agreement with earlier findings with yeast and mammalian EndoG (3).

To investigate the sequence preference for CPS-6, four 5′-end 32P-labeled 14-nucleotide single-stranded DNA containing zero, two, four, and six consecutive G nucleotides were used for protein-DNA binding experiments (Fig. 3D). The inactive CPS-6 mutant H148A was used for the protein-DNA binding assays to avoid DNA digestion by CPS-6. The dissociation constants measured between CPS-6(H148A) and DNA were increased hierarchically from (dG)6, (dG)4, (dG)2 to (dG)0 DNA (Kd, 0.53 ± 0.02 μm for (dG)6, 1.13 ± 0.73 μm for (dG)4, 2.55 ± 0.21 μm for (dG)2, and 5.14 ± 0.36 μm for (dG)0). Hence, this result shows that CPS-6 prefers to bind DNA with G-tract sequences.

Crystal Structure of Dimeric CPS-6 Reveals Basic DNA-binding Groove

To determine the crystal structure of CPS-6, the H148A mutant was used for crystallization screening experiments because the inactive H148A mutant can be expressed and purified in a larger quantity as compared with wild-type CPS-6. The H148A CPS-6 mutant was crystallized by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. X-ray diffraction data up to a resolution of 1.8 Å were collected. CPS-6 H148A mutant was crystallized in the space group P21 with one dimer per asymmetric unit. The crystal structure of CPS-6 (residues 63–305, H148A mutant) was determined by molecular replacement using the D. melanogaster EndoG structure (Protein Data Bank entry 3ISM) as the search model. The crystal structure was refined to an Rfactor of 16.6% for 41,201 reflections and an Rfree of 21.0% for 1,876 reflections from 37.6 to 1.8 Å (Table 1).

CPS-6 has a mixed αβ topology similar to that of Serratia nuclease (31) and EndA (32) with a central six-stranded β-sheet packed against the rest of the α-helices and β-strands (Fig. 4). The two ββα-metal finger motifs (shown in cyan), consisting of the conserved 145DRGH148 sequence in one of the β-strands, are located distantly on the two sides of the homodimer. A long β-strand (β8) from each protomer forms an antiparallel β-sheet at the dimeric interface. The two protomers are well packed with sufficient buried interfaces of 1392.2 Å2 to stabilize the dimeric structure.

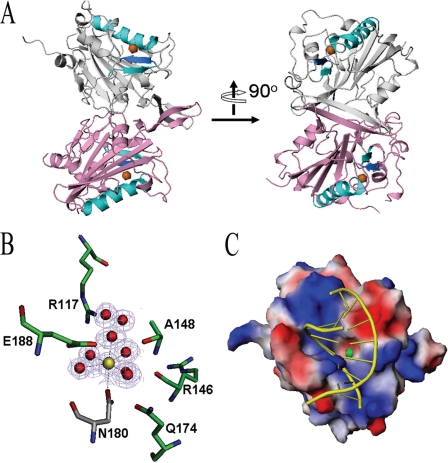

FIGURE 4.

Crystal structure of the Mg2+-bound CPS-6 H148A mutant. A, side view of the overall crystal structure of the dimeric CPS-6 (residues 63–305, H148A mutant) that was determined at 1.8 Å resolution (Protein Data Bank code 3S5B). The two protomers are displayed in pink and gray, respectively. The ββα-metal finger motifs are displayed in cyan with a Mg2+ ion (orange sphere) bound at the active site. B, omit map illustration for the active site of CPS-6 with the Mg2+ and the coordinated water molecules omitted for the map calculation (contoured at 3.0 σ). C, top view of the molecular model of CPS-6 bound with DNA. This model was constructed by superimposition of the ββα-metal finger motif in CPS-6 (residues 144–155 and 170–182) with that of the Vvn-DNA complex (Protein Data Bank code 1OUP) to determine where the DNA (GCGATCGC) is bound on CPS-6. A positively charged surface (in blue) near the active site of CPS-6 interacts well with the DNA phosphate backbone. The Mg2+ ion in the active site is displayed as a green ball.

Although magnesium ions were not present in the crystallization buffer, a Mg2+ was bound to Asn180 in the ββα-metal finger motif in the crystal structure of CPS-6. The omit map clearly shows that Mg2+ coordinated to Asn180 and five water molecules in an octahedral geometry (Fig. 4B). The conformation of the active site of CPS-6 is similar to other nucleases containing a ββα-metal finger motif in which His148 in the conserved 145DRGH148 sequence functions as a general base to activate a water molecule, and the Mg2+-bound water molecule likely functions as a general acid to provide a proton for the 3′-phosphate leaving group (24). Moreover, the amide side chain of the metal-binding residue Asn180 formed a hydrogen bond (2.69 Å) with the carboxylate side chain of Asp145, showing that Asp145 in the conserved 145DRGH148 sequence is important for stabilizing the metal ion-binding residue in the CPS-6 active site. On the other hand, Arg146 within the conserved 145DRGH148 sequence is likely involved in DNA binding (see the mutagenesis results in the next section).

The electrostatic potential mapping onto the CPS-6 structure further shows a basic groove extending on the molecule next to the active site (Fig. 4C). It has been shown that endonucleases containing a ββα-metal finger motif, such as I-PpoI, Vvn, and ColE7, bind to DNA in a similar mode, i.e. the relative orientations between the ββα-metal finger motif and DNA are comparable (33). A model of the CPS-6-DNA complex was thus constructed by superimposition of the ββα-metal motif of CPS-6 (residues 144–155 and 170–182) with that of Vvn (residues 77–82 and 118–129) in the Vvn-DNA complex (Protein Data Bank code 1OUP). After removal of Vvn, the DNA was well fitted onto the surface of CPS-6 with one phosphate backbone bound to the basic groove around the active site (Fig. 4C). We therefore suggest that the phosphate backbone of DNA is likely bound and digested at this basic groove in CPS-6.

Critical DNA-binding Residues in CPS-6

The CPS-6-DNA complex model suggests that DNA binds to a site located in proximity to the active site in the dimeric CPS-6 (Fig. 5A). A closer look at the model revealed five amino acid residues located near DNA: the two aromatic residues Phe122 and Phe166, and the three basic residues Arg117, Arg146, and Arg156 (Fig. 5B). To investigate the influence of these residues on the nuclease activity of CPS-6, site-directed mutagenesis was employed to selectively mutate those amino acid residues located within the interfacial region of the CPS-6-DNA complex model. We found that the nuclease activity of four mutant proteins, except R117A, was reduced significantly, with F122A, R156A, and F166A digesting the least amount of DNA and R146A digesting less DNA as compared with wild-type CPS-6 (Fig. 5D).

To determine whether these residues were involved in DNA binding, double mutants H148A/R117A, H148A/F122A, H148A/R146A, H148A/R156A, and H148A/F166A were constructed and purified to obtain inactive mutants that cannot digest DNA substrates (supplemental Fig. S2). Filter binding assays were employed to determine the dissociation constants between CPS-6 double mutants and single-stranded 48-nt DNA substrates. The dissociation constants had the same trend as those of activity assays (Fig. 5, D and E). H148A and H148A/R117A had highest affinity for DNA with a Kd of 245 ± 18 and 249 ± 20 nm, respectively. This result suggests that Arg117 was not involved in DNA binding and therefore R117A had retained DNase activity. Conversely, the Kd values for other mutants with low DNase activities were increased significantly (707 ± 88 nm for H148A/F122A, 468 ± 42 for H148A/R146A, 652 ± 111 nm for H148A/R156A, and 658 ± 74 nm for H148A/F166A). These results confirm our model suggesting that Phe122, Arg146, Arg156, and Phe166 are important amino acid residues that are involved in DNA binding and digestion in CPS-6.

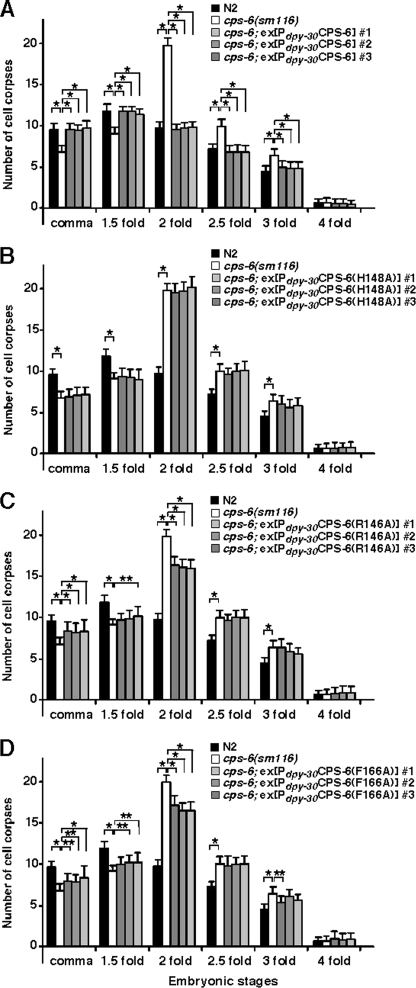

Residues at CPS-6 Catalytic Site or Involved in DNA Binding Are Important for Apoptosis Promoting Activity in C. elegans

To examine whether critical residues identified by structural predictions and in vitro nuclease assays are important for cps-6 cell killing activity in vivo, full-length CPS-6 or CPS-6 mutants was expressed in the cps-6-deficient strain (sm116) under the control of the dpy-30 gene promoter (Pdpy-30CPS-6), which directs ubiquitous gene expression in C. elegans (34). Compared with wild-type animals, the cps-6(sm116) mutant displayed a delay of cell death defect during embryonic development (4): less cell corpses were observed at early embryonic stages (comma and 1.5-fold stages), and more cell corpses were seen at later embryonic stages (2-, 2.5-, and 3-fold stages) (Fig. 6A). Expression of wild-type CPS-6 fully rescued the delay of cell death defect of the cps-6(sm116) mutant (Fig. 6A). In contrast, expression of CPS-6 harboring a catalytic site mutation (H148A) failed to rescue the cell death defect of cps-6(sm116) animals (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, expression of either CPS-6(R146A) or CPS-6(F166A), both of which showed significantly reduced nuclease activity (Fig. 5D), partially rescued the cps-6(sm116) mutant (Fig. 6, C and D). These results indicate that the DNA binding residues and the catalytic site of CPS-6 are important for its nuclease activity in vitro and pro-apoptotic activity in vivo.

FIGURE 6.

The cell death assay in C. elegans. Transgenic cps-6(sm116) animals expressing wild-type CPS-6 (A), CPS-6(H148A) (B), CPS-6(R146A) (C), or CPS-6(F166A) (D) under the control of the dpy-30 promoter were generated, and the numbers of cell corpses were scored. For each construct, the data were collected from three independent transgenic lines. The stages of transgenic embryos examined were: comma and 1.5-, 2-, 2.5-, 3-, and 4-fold. The y axis represents the average number of cell corpses scored, and the error bars show the standard deviations. Fifteen embryos were counted for each developmental stage. The significance of differences were determined by two-way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni comparison. *, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.05. All other points had p values > 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Catalytic Mechanism of CPS-6 in DNA Hydrolysis

In this study, we used CPS-6 as a model system for biochemical and structural analysis. CPS-6 shares a high sequence identity of 50, 49, 55 and 39% with human, bovine, fruit fly, and yeast EndoG, respectively (Fig. 1). We determined the high resolution crystal structure of CPS-6 and revealed that the highly conserved 145DRGH148 sequence is located within the ββα-metal finger motif. The geometry of the active site of CPS-6 is similar to the ones observed in other ββα-metal finger nucleases, all of which display a divalent metal ion bound to one or two amino acid residues and four or five water molecules, including I-PpoI (35), Hpy99I (36), T4 EndoVII (37), I-HmuI (38), Serratia nuclease (31), EndA (32), NucA (39), and Vvn (40).

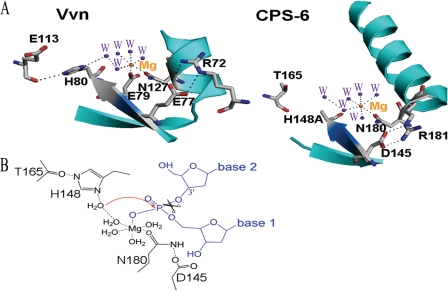

The comparison of the active site between CPS-6 and Vvn shows clearly that several catalytic residues are located at similar positions, including the general base residue His148 (mutated to Ala) in CPS-6 and His80 in Vvn, and the metal-binding residue Asn180 in CPS-6 and Asn127 in Vvn (Fig. 7A). The mutation of His148 to Ala abolished the enzyme activity of CPS-6 (Fig. 2C), supporting the role of His148 as the general base residue. The general base residue His80 in Vvn is polarized by a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl group of Glu113, where similarly the general base residue His148 in CPS-6 can be polarized by a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl group of Thr165. The metal ion-bound residue Asn127 in Vvn is fixed by a hydrogen bond network to the side chain of Glu77 and Arg72, where similarly, Asn180 in CPS-6 makes a hydrogen bond network to Asp145 and Arg181. In summary, these two nonspecific ββα-metal finger nucleases share similar active site architectures.

FIGURE 7.

The active site and proposed catalytic mechanism for CPS-6. A, the active site of CPS-6 shares a similar conformational arrangement with that of Vvn. The ββα-metal finger motif is colored in cyan, with the conserved 145DRGH148 sequence (and the corresponding 77EWEH80 sequence in Vvn) displayed in marine blue. B, schematic diagram of the proposed DNA hydrolysis mechanism by CPS-6. His148 acts as a general base to activate a water molecule, which in turn makes an in-line attack on the scissile phosphate. The magnesium ion stabilizes the phosphoanion transition state, and the Mg2+-bound water molecule functions as a general acid to provide a proton to the 3′-oxygen leaving group.

A parallel hydrolysis mechanism analogous to that of Vvn is therefore proposed for CPS-6, with His148 functioning as a general base to activate a water molecule for the in-line attack on the scissile phosphate, and a Mg2+-bound water molecule functioning as a general acid to provide a proton to the 3′-oxygen leaving group (Fig. 7B). Structural modeling of the CPS-6-DNA complex further reveals a basic DNA-binding groove constituted by basic residues Arg146 and Arg156 and nearby aromatic residues Phe122 and Phe166 (Fig. 5B). Site-directed mutagenesis confirmed that these basic and hydrophobic residues (Arg146, Arg156, Phe122, and Phe166) are critical for DNA binding and cleavage activity of CPS-6 (Fig. 5, C and D). Arginine residues are frequently located within protein-DNA interfaces and preferentially make hydrogen bonds to guanine (41). On the other hand, phenylalanine side chains often stack with DNA bases, with a preference for thymine, adenine, and cytosine, but not guanine (41, 42). It is speculated that the preference of EndoG for the cleavage of poly-(dG) tracks in DNA is linked in part to these basic and phenylalanine residues, particularly the preference of arginine residues for making hydrogen bonds with guanine bases.

Given the obvious impacts of these CPS-6 mutations on the nuclease activity of CPS-6 and CPS-6 DNA binding affinity (Fig. 5), it is of interest in this study to address the functional role of those mutants in vivo. An identical delay of cell death defect was observed in the catalytic site CPS-6 mutant (H148A) (lacking the DNase activity) to that of the cps-6-deficient animal, cps-6(sm116) (Fig. 6B). In contrast, expression of the CPS-6 DNA-binding site mutants (R146A and F166A) that still have residual DNase activity can partially rescue the cell death defect of the cps-6(sm116) mutant (Fig. 6, C and D). Therefore, the reduced nuclease activity of CPS-6 is positively correlated to its diminished cell killing activity in C. elegans.

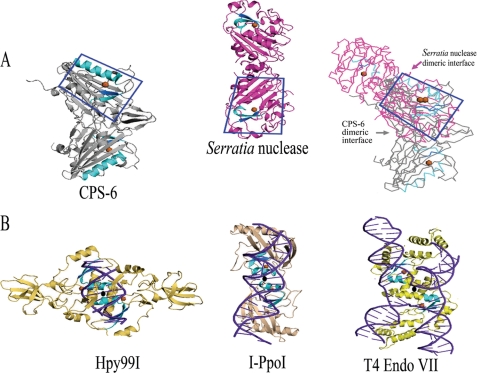

Different Dimeric Interfaces of CPS-6

The crystal structure of CPS-6 reveals an overall mixed αβ topology similar to that of Serratia nuclease (31) with a ββα-metal finger motif situated on one face of the central β-sheet. Apart from Serratia nuclease, a number of other ββα-metal finger nucleases are also homodimeric enzymes, including I-PpoI, Hpy99I, and T4 Endo VII. I-PpoI is a homing endonuclease that generates staggered products with four-nucleotide 3′ overhangs (43), whereas Hpy99I is a restriction endonuclease that generates staggered products with five-nucleotide 3′ overhangs (36). The reported crystal structures of I-PpoI-DNA and Hpy99I-DNA complexes show that the two ββα-metal finger motifs are orientated in a similar way, with close distances of 15.1 and 20.4 Å between the two Mg2+ ions in I-PpoI and Hpy99I, respectively (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the two ββα-metal finger motifs are located closely to the DNA sugar-phosphate backbones so that each monomer can make one nick on one strand of the double-stranded DNA to produce precisely the staggered end products. On the other hand, the two ββα-metal finger motifs in the Holliday junction resolvase T4 Endo VII are arranged more distantly (26.1 Å between the two Mg2+ ions) in a different relative orientation for the binding and cleavage of a four-way DNA junction (44). Interestingly, in these three protein-DNA complexes, the 2-fold symmetry axis between the two protomers roughly coincides with the 2-fold axis of the DNA substrates (see the 2-fold axis marked in Fig. 8B). Therefore, the relative orientation and distance of the two ββα-metal finger motifs in these dimeric endonucleases is actually restrained by their substrates.

FIGURE 8.

Structural comparison of nonspecific and site-specific dimeric ββα-metal finger nucleases. A, the overall folds of the two nonspecific nucleases, CPS-6 and Serratia nuclease, are similar. However, the dimeric interfaces are located in different regions as revealed by the superimposition of one protomer of the two proteins (boxed in the right panel). B, the crystal structures of the three site-specific endonucleases Hpy99I, I-PpoI, and T4 Endo VII in complex with their DNA substrates show that the two ββα-metal motifs are positioned and oriented next to the DNA sugar-phosphate backbones. The 2-fold symmetry (displayed as an oval) of the dimeric proteins coincides roughly with the 2-fold axis of the DNA substrates.

On the other hand, CPS-6 is a nonspecific endonuclease, and it shares not only a similar fold but also a similar activity to that of Serratia nuclease. However, CPS-6 dimerizes in a way completely different from that of Serratia nuclease. Superimposition of one of the protomers of the dimeric structure of CPS-6 and Serratia nuclease shows that the dimeric interfaces are located in different regions in the two proteins (Fig. 8A). As a result, the relative orientation and distances between the two ββα-metal finger motifs are different in the two nonspecific endonucleases: 44.5 Å in CPS-6 and 54.4 Å in Serratia nuclease for the distance between the two Mg2+ ions. This result indicates that each monomer of CPS-6 and Serratia nuclease likely interacts with DNA substrates independently. Hence, the relative orientation of the two distant ββα-metal finger motifs in these nonspecific nucleases is irrelevant. Why CPS-6 and Serratia nuclease did not evolve into monomeric enzymes, such as the nonspecific nucleases EndA, NucA and Vvn, is unknown. In the future, it will be necessary to cocrystallize CPS-6 with DNA to further elucidate its substrate binding mode and the basis of sequence preference.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM79097 (to D. X.). This work was also supported by research grants from Academia Sinica (to H. Y.) and the National Science Council, Taiwan (to H. Y.). This work was also supported in part by the National Research Program for Genomic Medicine through the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3S5B) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- EndoG

- endonuclease G

- AIF

- apoptosis-inducing factor

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- CAPS

- 3-(cyclohexylamino)propanesulfonic acid

- CAPSO

- N-cyclohexyl-2-hydroxyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ruiz-Carrillo A., Renaud J. (1987) Endonuclease G. A (dG)n × (dC)n-specific DNase from higher eukaryotes. EMBO J. 6, 401–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cummings O. W., King T. C., Holden J. A., Low R. L. (1987) Purification and characterization of the potent endonuclease in extracts of bovine heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 2005–2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Low R. L. (2003) Mitochondrial endonuclease G function in apoptosis and mtDNA metabolism. A historical perspective. Mitochondrion 2, 225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parrish J., Li L., Klotz K., Ledwich D., Wang X., Xue D. (2001) Mitochondrial endonuclease G is important for apoptosis in C. elegans. Nature 412, 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li L. Y., Luo X., Wang X. (2001) Endonuclease G is an apoptotic DNase when released from mitochondria. Nature 412, 95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Napirei M., Karsunky H., Zevnik B., Stephan H., Mannherz H. G., Möröy T. (2000) Features of systemic lupus erythematosus in DNase1-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 25, 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kawane K., Ohtani M., Miwa K., Kizawa T., Kanbara Y., Yoshioka Y., Yoshikawa H., Nagata S. (2006) Chronic polyarthritis caused by mammalian DNA that escapes from degradation in macrophages. Nature 443, 998–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu X., Zou H., Slaoghter C., Wang X. (1997) DFF, a heterodimeric protein that functions downstream of caspase-3 to trigger DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. Cell 89, 175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Enari M., Sakahira H., Yokoyama H., Okawa K., Iwamatsu A., Nagata S. (1998) Nature 391, 42–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Widlak P., Garrard W. T. (2005) Discovery, regulation, and action of the major apoptotic nucleases DFF40/CAD and endonuclease G. J. Cell Biochem. 94, 1078–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang X., Yang C., Chai J., Shi Y., Xue D. (2002) Mechanisms of AIF-mediated apoptotic DNA degradation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 298, 1587–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parrish J. Z., Yang C., Shen B., Xue D. (2003) CRN-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans FEN-1 homologue, cooperates with CPS-6/EndoG to promote apoptotic DNA degradation. EMBO J. 22, 3451–3460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kalinowska M., Garncarz W., Pietrowska M., Garrard W. T., Widlak P. (2005) Regulation of the human apoptotic DNase/RNase endonuclease G. Involvement of Hsp70 and ATP. Apoptosis 10, 821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parrish J. Z., Xue D. (2003) Functional genomic analysis of apoptotic DNA degradation in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 11, 987–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu Y. C., Stanfield G. M., Horvitz H. R. (2000) Genes & Dev. 14, 536–548 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakagawa A., Shi Y., Kage-Nakadai E., Mitani S., Xue D. (2010) Caspase-dependent conversion of Dicer ribonuclease into a death-promoting deoxyribonuclease. Science 328, 327–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lai H. J., Lo S. J., Kage-Nakadai E., Mitani S., Xue D. (2009) Plos One 10, e7348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Irvine R. A., Adachi N., Shibata D. K., Cassell G. D., Yu K., Karanjawala Z. E., Hsieh C. L., Lieber M. R. (2005) Generation and characterization of endonuclease G null mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 294–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. David K. K., Sasaki M., Yu S. W., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L. (2006) EndoG is dispensable in embryogenesis and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 13, 1147–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cote J., Ruiz-Carrillo A. (1993) Primers for mitochondrial DNA replication generated by endonuclease G. Science 261, 765–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang K. J., Ku C. C., Lehman I. R. (2006) Endonuclease G. A role for the enzyme in recombination and cellular proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 8995–9000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buttner S., Eisenberg T., Carmona-Gutierrez D., Ruli D., Knauer H., Ruckenstuhl C., Sigrist C., Wissing S., Kollroser M., Frohlich K. U., Sigrist S., Madeo F. (2007) DNA methylation controls the inducibility of the mouse metallothionein-I gene lymphoid cells. Cell 25, 233–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schafer P., Scholz S. R., Gimadutdinow O., Cymerman I. A., Bujnicki J. M., Ruiz-Carrillo A., Pingoud A., Meiss G. (2004) Structural and functional characterization of mitochondrial EndoG, a sugar non-specific nuclease which plays an important role during apoptosis. J. Mol. Biol. 338, 217–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hsia K. C., Li C. L., Yuan H. S. (2005) Structural and functional insight into sugar-nonspecific nucleases in host defense. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 126–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Temme C., Weissbach R., Lilie H., Wilsom C., Meinhart A., Meyer S., Golbik R., Schierhorn A., Wahle E. (2009) The Drosophila melanogaster gene cg4930 encodes a high affinity inhibitor for endonuclease G. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8337–8348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loll B., Gebhardt M., Wahle E., Meinhart A. (2009) Crystal structure of the EndoG/EndoGI complex. Mechanism of EndoG inhibition. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 7312–7320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brenner S. (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mello C. C., Krame J. M., Stinchcomb D., Ambros V. (1992) Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans. Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10, 3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gu T., Orita S., Han M. (1998) Caenorhabditis elegans SUR-5, a novel but conserved protein, negatively regulates LET-60 Ras activity during vulval induction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4556–4564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu S. L., Li C. C., Chen J. C., Chen Y. J., Lin C. T., Ho T. Y., Hsiang C. Y. (2009) Mutagenesis identifies the critical amino acid residues of human endonuclease G involved in catalysis, magnesium coordination, and substrate specificity. J. Biomed. Sci. 16, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller M. D., Cai J., Krause K. L. (1999) The active site of Serratia endonuclease contains a conserved magnesium-water cluster. J. Mol. Biol. 288, 975–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moon A. F., Midon M., Meiss G., Pingoud A., London R. E., Pedersen L. C. (2011) Structural insights into catalytic and substrate binding mechanisms of the strategic EndA nuclease from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2943–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsia K. C., Chak K. F., Liang P. H., Cheng Y. S., Ku W. Y., Yuan H. S. (2004) DNA binding and degradation by the HNH protein ColE7. Structure 12, 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsu D. R., Meyer B. J. (1994) The dpy-30 gene encodes an essential component of the Caenorhabditis elegans dosage compensation machinery. Genetics 137, 999–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Galburt E. A., Chevalier B., Tang W., Jurica M. S., Flick K. E., Raymond J., Monnat J., Stoddard B. L. (1999) A novel endonuclease mechanism directly visualized for I-PpoI. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 1096–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sokolowska M., Czapinska H., Bochtler M. (2009) Crystal structure of the ββα-Me type II restriction endonuclease Hpy99I with target DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 3799–3810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raaijmakers H., Vix O., Törõ I., Golz S., Kemper B., Suck D. (1999) X-ray structure of T4 endonuclease VII. A DNA junction resolvase with a novel fold and unusual domain-swapped dimer architecture. EMBO J. 18, 1447–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shen B. W., Landthaler M., Shub D. A., Stoddard B. L. (2004) DNA binding and cleavage by the HNH homing endonuclease I-HmuI. J. Mol. Biol. 342, 43–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ghosh M., Meiss G., Pingoud A., London R. E., Pedersen L. C. (2005) Structural insights into the mechanism of nuclease A, a ββα metal nuclease from Anabaena. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27990–27997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li C. L., Hor L. I., Chang Z. F., Tsai L. C., Yang W. Z., S. Yuan H. (2003) DNA binding and cleavage by the periplasmic nuclease Vvn. A novel structure with a known active site. EMBO J. 22, 4014–4025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luscombe N. M., Laskowski R. A., Thornton J. M. (2001) Amino acid-base interactions. A three-dimensional analysis of protein-DNA interactions at an atomic level. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 2860–2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hsiao Y. Y., Yang C. C., L., L. C., Lin J. L., Duh Y., Yuan H. S. (2011) Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 236–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Flick K. E., Jurica M. S., Jr., R. J., Stoddard B. L. (1998) DNA binding and cleavage by the nuclear intron-encoded homing endonuclease I-PpoI. Nature 394, 96–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Biertümpfel C., Yang W., Suck D. (2007) Crystal structure of T4 endonuclease VII resolving a Holliday junction. Nature 449, 616–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.