Advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), defined as gene therapy medicinal products (GTMPs), somatic cell therapy medicinal products, and tissue-engineered products (TEPs),1,2 constitute a major class of innovative therapeutics that are being investigated as treatments for several diseases. Despite the success of many such products in animal studies, few have reached more advanced regulatory milestones in Europe (Figure 1), such as ATMP Certification from the Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA),3 regulatory scientific advice from the EMA,4 or a marketing authorization application at the EMA.5 Therefore, there is a need to identify the major stakeholders in the development of such products and to investigate why they have been unable to move these products farther down the development pipeline. As members of the CAT and EMA, we analyzed the data in the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) database (https://eudract.ema.europa.eu). Analysis of 318 ATMP trials performed between 2004 and 2010 revealed that the main sponsors are academia, charities, and small companies. This may have implications for the further evolution of the regulatory framework for ATMPs given that such stakeholders often have limited financial resources or regulatory expertise, leading to a “translational gap” that must be proactively closed by regulators.

Figure 1.

Regulatory pathways for ATMPs in Europe. The usual sequence in which procedures are requested by applicants. Note that all procedures can be requested at any time during development. ATMP, advanced therapy medicinal product; CAT, Committee for Advanced Therapies; EMA, European Medicines Agency; SME, small and medium-sized enterprise.

A consolidated regulatory framework for the development of ATMPs in Europe came into force in 2008 (ref. 2). The CAT at the EMA plays a central role in this regulatory oversight.6 It has been assumed that ATMPs are developed mainly by academia; academic spin-offs; or small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), rather than by large pharmaceutical companies. To test this hypothesis, we made use of the EudraCT database, which registers all clinical trials of medicinal products conducted by both commercial and noncommercial sponsors in European countries (European Union/European Economic Area) from May 2004 onward (Supplementary Materials and Methods). The EudraCT database was established in accordance with Directive 2001/20/EC (ref. 7) to improve the supervision of clinical trials across Europe and the protection of individuals participating in these trials.

We identified 318 distinct clinical trials of 250 individual ATMPs registered in EudraCT and 173 unique commercial and noncommercial sponsors of these trials (Figure 2a and Supplementary Table S1). A slight majority of clinical trials in Europe were sponsored by either academia or charitable organizations. Forty percent were sponsored by commercial entities, the vast majority by SMEs or non-large pharmaceutical companies. A greater fraction of orphan ATMPs (for rare diseases) was being developed by commercial sponsors than by noncommercial sponsors, and trials of GTMPs were more likely to be supported by commercial sponsors than by noncommercial sponsors (Figure 2a). Interestingly, there was only one academic sponsor evaluating an orphan ATMP, which is consistent with our empirical experience that the development of gene therapies for inherited disorders in particular appears to be the domain of a handful of charities or small companies that specialize in this area. Indeed, the manufacturing of a GTMP requires a technical infrastructure that academia might historically have lacked, although this situation may be changing.

Figure 2.

The ATMP landscape in Europe 2004–2010. ATMP, advanced therapy medicinal product; CA, cancer; CBMP, cell-based medicinal product; DC, dendritic cell; GTMP, gene therapy medicinal product; HBSC, hematopoietic blood stem cell; MCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; SCTMP, somatic cell therapy medicinal product; SME, small and medium-sized enterprise; TEP, tissue-engineered product; Tx, transplantation.

Just over three-quarters of the products were cell-based medicinal products (CBMPs), which include both somatic cell therapy and TEPs (Figure 2b and Supplementary Table S1). The remainder represented GTMPs including genetically modified cells. The CBMPs could be further subdivided into dendritic cells (DCs), mesenchymal stem cells, substantially manipulated hematopoietic or bone marrow–derived stem cells for homologous use, hematopoietic or bone marrow stem cells for heterologous use, TEPs, or “other CBMPs.” There was a bias toward early-stage trials, and the predominant stage of development was phase II (see Supplementary Tables S2 and S3); only 20% of the trials had reached the confirmatory stage of development. The most predominant indication was oncology (solid tumors, Figure 2c), followed by cardiovascular diseases and hematology, including hematological malignancies. The most widely studied solid tumor was melanoma, with a predominance of somatic cell therapy including DCs.

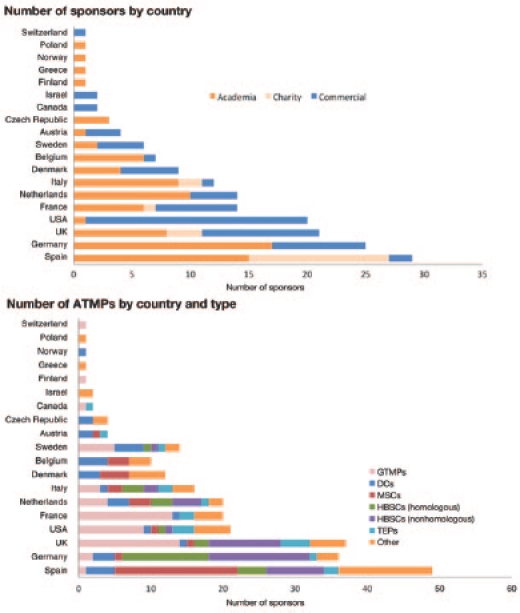

Overall, the results support the hypothesis that the vast majority of stakeholders developing ATMPs are academic institutions, charities, SMEs, or other small companies. Among commercial sponsors, small companies represent by far the majority. In the majority of trials conducted in single-member states, the sponsor was also based in the state in question. These data, together with the high prevalence of academic sponsors, point to a high prevalence of national clinical research (Figure 3). This finding may reflect the fact that prior to implementation of the ATMP legislation in 2009, the definition and regulatory approach to ATMPs were not harmonized across Europe.8 Thus, the regulatory and financial landscape may have led to a preponderance of national trials or, in some cases, to a determination by the relevant national authorities that the products were not medicines.

Figure 3.

Numbers of ATMPs and sponsors by country and type. ATMP, advanced therapy medicinal product; DC, dendritic cell; GTMP, gene therapy medicinal product; HBSC, hematopoietic blood stem cell; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; TEP, tissue-engineered product.

There has been a constant increase in the number of clinical trials evaluating ATMPs, with a focus on CBMPs, including stem cell–based medicinal products. The CAT recently announced concern over the unauthorized use of stem cell–based medicinal products (so-called stem cell tourism9), and the strong representation of stem cell–based medicinal products within the evaluated cohort of clinical trials is encouraging, as this is expected to generate important scientific insight into their clinical use. A considerable number of these products were defined as hematopoietic stem cells or bone marrow–derived stem cells for nonhomologous use. For example, minimally manipulated bone marrow containing stem cells administered to an infarcted myocardium would be considered a nonhomologous use—even in an autologous setting—because the intended therapeutic function (regeneration of myocardial tissue) of the product differs from its normal role in the donor (formation of blood cells). Scientific assessment of such products will be challenging from a regulatory perspective. For example, the usual criteria of product quality, such as “identity,” “purity,” “potency,” or “mechanism of action,” may be more difficult to establish. It is important to clearly define the manufacturing process because cells can be impacted by various factors during their isolation and processing.10 However, this validation and determination of quality may not be straightforward—for example, the inherent variability of bone marrow would need to be distinguished from variability arising from the manufacturing process. The CAT must therefore balance its approach to the regulation of such products by being cognizant of such issues while nevertheless fulfilling its role to ensure that these products are safe and efficacious with a consistent quality.

There are several inherent limitations to these analyses. Data for clinical trials that were initiated before implementation of the clinical trials directive7 in 2004, and therefore before creation of the EudraCT, do not appear in the database, and thus the data in EudraCT do not provide a complete picture of the clinical trials ongoing at the time of our analysis. It should also be considered that before the implementation of the definition of ATMPs,1,2 some cell therapy products may not have been considered medicines by the research community and the relevant sponsors may therefore not have sought clinical trial authorization or have entered the trial into EudraCT.

The present analysis confirms that, in Europe, academic groups, charities, and small companies are the major stakeholders developing ATMPs. This is an important finding, for these stakeholders tend to have limited resources with regard to both financing and the capacity to navigate the required regulatory procedures. The increasing number of academics developing ATMPs will require that regulators more clearly communicate their requirements and expectations so as to help academics become more familiar with the “language” and approach to regulation. These issues also apply to investigators working in small companies. The CAT has identified this important roadblock in its Work Programme 2010–2015 (ref. 11), which lays out important milestones for CAT to bridge these communication gaps proactively, within the existing legal framework. Likewise, the large number of small companies developing ATMPs may pose other challenges for the field. A recent regulatory analysis by Regnstrom et al.12 suggests that company size may be an independent predictor of outcome of a marketing authorization application to the EMA: the smaller the company, the more likely a negative outcome. Similarly, the study suggests that smaller companies are developing a larger proportion of orphan medicinal products than larger companies. GTMPs tend to be targeted to rare or ultrarare diseases that represent a serious unmet medical need. As such, the analysis by Regnstrom et al. raises the very real possibility that small companies (or academia) developing gene therapies or other ATMPs for rare diseases may face a high probability of failure. In the aftermath of the exit of a major player from the field of stem cell medicinal product development13 also due to “regulatory complexities,”14 we consider it important to stress that we as regulators are aware of the idiosyncrasies of the ATMP field. In this context, we draw attention to existing ways that regulators can provide guidance to developers of ATMPs (see Figure 1 and refs. 5 and 6), such as scientific advice4 or briefing meetings with the EMA Innovation Task Force,15 or ways in which the CAT can provide help to sponsors with their product development, such as via ATMP classification16 or certification.3 These incentives should assist developers of ATMPs by beginning a dialogue with regulators sufficiently early in the process so as to identify any likely difficulties. Indeed, Regnstrom et al. also found a strong association between a positive outcome of a marketing authorization procedure and requests for and compliance with regulatory scientific advice. Direct interaction with regulators thus appears to be a key predictor of success.12

The increasing cumulative number of clinical trials is reassuring. The fact that the majority of the trials under way during the period of our study were at an early stage indicates that the individuals involved could still benefit from interaction with regulators. The EudraCT analysis provides stronger evidence for this than a simple analysis of the number of classification requests or scientific advice procedures. The EudraCT database is not selective for sponsors who are already familiar with the regulatory system because trial registration is legally mandated and not biased by the extent of regulatory familiarity. As such, this analysis provides a more “real world” picture of the ATMP landscape in Europe. However, there may be an unrecorded population of clinical trials that were not entered because of lack of a unified ATMP definition before 2009 or arising from cases in which a product was used on a single-case basis in individual patients without being defined as a clinical trial and therefore not entered in EudraCT by the treating physician.

With its Work Programme 2010–2015 (ref. 11), the CAT has already started several proactive initiatives to create dialogue and a fruitful environment for ATMPs, such as the creation of “focus groups” in which regulators and stakeholders meet and discuss particular aspects of ATMP development on a conceptual level (for example, nonclinical development and its limitations)17 or organization of scientific workshops with learned societies such as the joint Satellite Workshop on ATMPs in Brighton, UK, held jointly by the CAT and the European Society for Gene and Cell Therapy in October 2011 (ref. 18). Clearly, the CAT must remain proactive to help further close the “translational gap” of ATMP development in the European Union.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carl Pereira for his excellent work on the FileMaker database and Vincenzo Salvatore, Fergus Sweeney, and Hans-Georg Eichler from the EMA for valuable comments on the manuscript.

The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the authors and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of the EMA or one of its committees or working parties.

Supplementary Material

Sponsors of ATMPs under clinical development and the type of ATMP from 2004 to 2010 in Europe.

Number of clinical studies of ATMPs in 2004–2010 in Europe.

Qualitative description of indications/conditions studied with ATMPs between 2004 and 2010 in Europe.

References

- European Commission (2009) Official Journal of the European Union 15.9.2009. L242/3-12; Commission Directive 2009/120/EC of 14 September 2009 amending Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use as regards advanced therapy medicinal products. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council (2007) Official Journal of the European Union 10.12.2007. L324/121-137; Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 November 2007 on advanced therapy medicinal products and amending Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (2012). Certification procedure for SMEs < http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/ regulation/general/general_content_000300.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058007f4bd >.

- European Medicines Agency (2012) Scientific advice and protocol assistance < http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/ general_content_000049.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05800229b9&jsenabled=true >.

- Schneider CK., and, Schäffner-Dallmann G. Typical pitfalls in applications for marketing authorization of biotechnological products in Europe. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:893–899. doi: 10.1038/nrd2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT); CAT Scientific Secretariat, Schneider, CK, Salmikangas, P, Jilma, B, Flamion, B, Todorova, LR, Paphitou, A et al Challenges with advanced therapy medicinal products and how to meet them. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:195–201. doi: 10.1038/nrd3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (2001). Commission Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use . Official Journal of the European Union 1.5.2001. L121/34-44; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanzenbacher R, Dwenger A, Schuessler-Lenz M, Cichutek K., and, Flory E. European regulation tackles tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1089–1091. doi: 10.1038/nbt1007-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) and CAT Scientific Secretariat (2010) Use of unregulated stem-cell based medicinal products. Lancet. 376:514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debey S, Schoenbeck U, Hellmich M, Gathof BS, Pillai R, Zander T.et al. (2004Comparison of different isolation techniques prior gene expression profiling of blood derived cells: impact on physiological responses, on overall expression and the role of different cell types Pharmacogenomics J 4193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (2010). Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) Work Programme 2010–2015 < http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/ document_library/Work_programme/2010/11/WC500099029.pdf >.

- Regnstrom J, Koenig F, Aronsson B, Reimer T, Svendsen K, Tsigkos S.et al. (2010Factors associated with success of market authorisation applications for pharmaceutical drugs submitted to the European Medicines Agency Eur J Clin Pharmacol 6639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. Stem-cell pioneer bows out. Nature. 2011;479:459. doi: 10.1038/479459a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geron 2011News release: Geron to focus on its novel cancer programs; < http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/14/idUS242102+14-Nov-2011+BW20111114 >. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (2006). Mandate of the EMEA Innovation Task Force (ITF) EMEA/20220/06 < http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/ document_library/Other/2009/10/WC500004912.pdf >.

- European Medicines Agency (2012). ATMP classification < http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/ regulation/general/general_content_000296.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058007f4bc > ( 2012

- European Medicines Agency (2011) Report from CAT-Interested Parties Focus Groups (CAT-IPs FG) on non-clinical development of ATMPs EMA/CAT/134694/2011 < http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/ Report/2011/03/WC500103895.pdf >.

- European Medicines Agency and European Society for Gene and Cell Therapy (ESGCT) (2011) Conference Programme CAT-ESGCT Satellite Workshop: Advanced therapy medicinal products: from promise to reality. Regulatory path for translation of research to commercial medicinal products < http://www.esgct.eu/resources/pdf/ congress/2011/programme_EMA-CAT.pdf >.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sponsors of ATMPs under clinical development and the type of ATMP from 2004 to 2010 in Europe.

Number of clinical studies of ATMPs in 2004–2010 in Europe.

Qualitative description of indications/conditions studied with ATMPs between 2004 and 2010 in Europe.