Abstract

Background

Carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) is an useful surrogate marker of cardiovascular disease. Associations between uric acid (UA), metabolic syndrome (MetS) and carotid IMT have been reported, but findings regarding the relationship have been inconsistent.

Methods

A total of 1,579 Japanese elderly subjects aged ≥65 years {663 men aged, 78 ± 8 (mean ± standard deviation) years and 916 women aged 79 ± 8 years} were divided into 4 groups according to UA quartiles. We first investigated the association between UA concentrations and confounding factors including MetS; then, we assessed whether there is an independent association of UA with carotid IMT and atherosclerosis in participants subdivided according to gender and MetS status.

Results

Carotid IMT was significantly increased according to the quartiles of UA in both genders without MetS and women with MetS. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that odds ratio (OR) {95% confidence interval (CI)} in men for carotid atherosclerosis was significantly increased in the third (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.02-3.02), and fourth quartiles (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.12-3.60) of UA compared with that in the first quartile of UA, and the OR in women was significantly increased in the fourth quartile (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.30-3.39). Similarly, the ORs were significantly associated with increasing quartiles of UA in both genders without MetS, but not necessarily increased in those with MetS.

Conclusions

UA was found to be an independent risk factor for incidence of carotid atherosclerosis in both genders without MetS.

Keywords: uric acid, metabolic syndrome, carotid atherosclerosis, cardiovascular risk factor, gender

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of metabolic abnormalities defined as the clustering of several cardiovascular risk factors in an individual that include visceral obesity, insulin resistance, raised blood pressure (BP), hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterolemia, and impaired fasting plasma glucose (FPG) [1,2], and that it is a predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [3-5]. Population-based studies have shown that MetS is quite common, affecting 13.3~24.4% of Japanese men ≥30 years of age [6], and its prevalence is increasing with the continuous increase in obesity prevalence in Japan.

Uric Acid (UA) is the metabolic end product of purine metabolism in humans; excess accumulation can lead to various diseases [7]. Many previous studies have shown that increased UA levels are also associated with components of MetS and often accompanied by obesity, raised BP [8], hyperlipidemia [9], glucose intolerance [10], and CVD clustering [11], all of which play a causal role in the pathogenesis of CVD. Thus, UA seems to be merely an independent risk factor or marker for atherosclerosis [12,13]. However, its importance as a risk factor is still controversial. Sakata et al. showed that UA levels are not related to increased risk of death from all causes, including CVD and stroke in 8,172 Japanese participants aged ≥30 years [14]. We have demonstrated that UA is more strongly associated with MetS in women than in men, and associated with the prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis {intima-media thickness (IMT) ≥1.0 mm} only in men without MetS but not in men with MetS or in women with or without MetS [15]. Associations between UA, MetS and carotid IMT have been reported, but few of the studies have been conducted in Japanese subjects.

In the present study, we first investigated the association between UA levels and confounding factors including MetS; currently defined as at least 3 of the 5 following conditions: visceral obesity, raised BP, hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL cholesterolemia, and impaired FPG. In addition, we also assessed whether there is an independent association of UA with carotid atherosclerosis in individuals subdivided according to gender and MetS status.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Subjects for this investigation were recruited from among consecutive elderly patients aged ≥65 years visited the medical department of Seiyo Municipal Nomura Hospital. Participants with severe cardio-renal or nutritional disorders that would affect BP, lipid and glucose metabolism were excluded. Thus, 1,579 patients were enrolled in the study. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Seiyo Municipal Nomura Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Evaluation of Risk Factors

Information on demographic characteristics and risk factors were collected using the clinical files in all cases. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of the height (in meters). We measured BP in the right upper arm of patients in a sedentary posture using a standard sphygmomanometer or an automatic oscillometric BP recorder. Smoking status was defined as the number of cigarette packs per day multiplied by the number of years smoked (pack·year) irrespective of the differentiation of current and past smoking status: never, light (< 20 pack·year), heavy (≥20 pack·year). Alcohol consumption was classified into non-drinker and drinker (available data, n = 1,145). Histories of antihypertensive, antilipidemic, and antidiabetic medication use were also evaluated. Moreover, ischemic stroke and ischemic heart disease were defined as CVD. Total cholesterol (T-C), triglyceride (TG), HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), FPG, and UA were measured under a fasting condition. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level was calculated by the Friedewald formula [16], and patients with TG levels ≥400 mg/dl were excluded. The mean UA was significantly lower in women [5.1 ± 2.0 {mean ± standard deviation (SD)} mg/dl] than in men (5.7 ± 2.0 mg/dl; p < 0.001). Therefore, sex-specific quartiles of UA were used. The mean (range) UA values of 3.5 (0.8 to 4.3), 5.0 (4.4 to 5.5), 6.1 (5.6 to 6.8), and 8.4 (6.9 to 16.1) mg/dl were used for men, and 3.1 (0.5 to 3.8), 4.3 (3.9 to 4.7), 5.3 (4.8 to 6.0), and 7.7 (6.1 to 15.4) were used for women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects

| Men | Quartile of serum uric acid | Women | Quartile of serum uric acid | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Characteristics |

Uric acid range (mg/dL) | UA-1 0.8-4.3 N = 169 |

UA-2 4.4-5.5 N = 171 |

UA-3 5.6-6.8 N = 163 |

UA-4 6.9-16.1 N = 160 |

P for trend* |

UA-1 0.5-3.8 N = 247 |

UA-2 3.9-4.7 N = 213 |

UA-3 4.8-6.0 N = 235 |

UA-4 6.1-15.4 N = 221 |

P for trend* |

| Age (years) | 76 ± 8 | 78 ± 7 | 78 ± 8 | 79 ± 7 | 0.004 | 79 ± 8 | 78 ± 8 | 79 ± 8 | 82 ± 8 | < 0.001 | |

| Body mass index†(kg/m2) | 21.3 ± 4.6 | 21.9 ± 3.2 | 21.9 ± 3.9 | 21.8 ± 4.0 | 0.372 | 21.2 ± 3.6 | 22.1 ± 3.4 | 22.8 ± 4.8 | 22.3 ± 4.8 | < 0.001 | |

| Smoking status‡(never/light/heavy, %) | 26.0/20.7/53.3 | 32.2/19.9/48.0 | 36.2/17.8/46.0 | 35.6/16.9/47.5 | 0.517 | 99.2/0.4/0.4 | 96.2/0.5/3.3 | 65.7/1.3/3.0 | 93.7/2.7/3.6 | 0.043 | |

| Alcohol consumption¶, N (%) | 78 (67.8) | 70 (60.9) | 65 (59.1) | 65 (66.3) | 0.470 | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.8) | 6 (3.3) | 5 (2.8) | 0.286 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 132 ± 22 | 141 ± 22 | 139 ± 24 | 136 ± 25 | 0.003 | 138 ± 21 | 139 ± 20 | 138 ± 21 | 136 ± 28 | 0.552 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76 ± 14 | 78 ± 13 | 77 ± 13 | 76 ± 14 | 0.672 | 76 ± 13 | 76 ± 11 | 76 ± 13 | 72 ± 16 | 0.001 | |

| Antihypertensive medication, N (%) | 65 (38.5) | 75 (43.9) | 88 (54.0) | 82 (51.3) | 0.019 | 116 (47.0) | 105 (49.3) | 140 (59.6) | 146 (66.1) | < 0.001 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 167 ± 46 | 168 ± 42 | 164 ± 41 | 171 ± 45 | 0.505 | 190 ± 40 | 188 ± 42 | 193 ± 43 | 181 ± 44 | 0.025 | |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 102 ± 38 | 104 ± 33 | 95 ± 35 | 105 ± 38 | 0.061 | 118 ± 33 | 114 ± 35 | 120 ± 37 | 110 ± 35 | 0.016 | |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 68 (52-93) | 73 (56-98) | 76 (57-112) | 89 (69-127) | < 0.001 | 69 (54-93) | 80 (59-109) | 92 (69-124) | 94 (67-120) | < 0.001 | |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 49 ± 19 | 47 ± 15 | 51 ± 18 | 45 ± 15 | 0.024 | 57 ± 17 | 56 ± 18 | 53 ± 15 | 51 ± 17 | < 0.001 | |

| Antilipidemic drug use, N (%) | 9 (5.3) | 7 (4.1) | 8 (4.9) | 8 (5.0) | 0.959 | 17 (6.9) | 13 (6.1) | 17 (7.2) | 26 (11.8) | 0.115 | |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 119 (98-152) | 112 (95-141) | 113 (96-150) | 115 (96-139) | 0.404 | 112 (97-146) | 108 (94-140) | 109 (92-130) | 118 (97-155) | 0.061 | |

| Antidiabetic medication, N (%) | 50 (29.6) | 35 (20.5) | 29 (17.8) | 37 (23.1) | 0.063 | 47 (19.0) | 48 (22.5) | 43 (18.3) | 59 (26.7) | 0.112 | |

| Metabolic syndrome, N(%) | 32 (18.9) | 50 (29.2) | 44 (27.0) | 54 (33.8) | 0.022 | 62 (25.1) | 71 (33.3) | 87 (37.0) | 97 (43.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Cardiovascular disease, N (%) | 65 (38.5) | 85 (49.7) | 82 (50.3) | 83 (51.9) | 0.055 | 87 (35.2) | 84 (39.4) | 97 (41.3) | 91 (41.2) | 0.448 | |

| Ischemic stroke, N (%) |

59 (34.9) | 74 (43.3) | 73 (44.8) | 75 (46.9) | 0.131 | 77 (31.2) | 73 (34.3) | 78 (33.2) | 69 (31.2) | 0.869 | |

| Ischemic heart disease, N (%) |

11 (6.5) | 15 (8.8) | 17 (10.4) | 16 (10.0) | 0.592 | 15 (6.1) | 16 (7.5) | 21(8.9) | 30 (13.6) | 0.031 | |

LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein. Plus-minus values are means ± standard deviation. †Body mass index was calculated using weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. ‡Smoking status: daily consumption (pack)×duration of smoking (year): never, light (< 20 pack year), and heavy (≥20 pack·year). ¶Alcohol consumption was classified into non-drinker and drinker (available data, n = 1,145). Data for triglycerides and fasting plasma glucose were skewed, and are presented as the median (interquartile range) and were log-transformed for analysis. *P-value: ANOVA or χ2-test.

Ultrasound image analysis

An ultrasonograph (Hitachi EUB-565, Aloka SSD-2000, or Prosound-α6) equipped with a 7.5 MHz linear type B-mode probe was used by a specialist in ultrasonography to evaluate sclerotic lesions of the common carotid arteries on a day close to the day of blood biochemistry analysis (within 2 days). Patients were asked to assume a supine position, and the bilateral carotid arteries were observed obliquely from the anterior and posterior directions. We measured the thickness of the intima-media complex (IMT) on the far wall of the bilateral common carotid artery about 10 mm proximal to the bifurcation of the carotid artery (as the image at that site is more clearly depicted than that at the near wall) [17,18] as well as the wall thickness near the 10 mm point on a B-mode monitor. We then used the mean value for analysis. Carotid plaques were considered as localized thickening and the echo luminance included those equal to high echogenic structures encroaching into the vessel lumen through common carotid artery to carotid bifurcation [17]. Carotid atherosclerosis was defined as IMT ≥1.0 mm or plaque lesion [17-19].

MetS

We applied condition-specific cutoff points for MetS based on the modified criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program's Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP-ATP) III report [2]. MetS was defined as subjects with at least three or more of the following five conditions: 1) obesity: BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2 according to the guidelines of the Japanese Society for the Study of Obesity (waist circumference was not available in this study) [20,21]; 2) raised BP with a systolic BP (SBP) ≥130 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥85 mmHg, and/or current treatment for hypertension; 3) hypertriglyceridemia with a TG level ≥150 mg/dL; 4) low HDL cholesterolemia with a HDL-C level < 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women and/or current treatment for dyslipidemia; and 5) impaired fasting glucose with a FPG level ≥100 mg/dL and/or current treatment for diabetes.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), unless otherwise specified, and in the cases of parameters with non-normal distributions (TG, FPG), the data are shown as median (interquartile range) values. In all analyses, parameters with non-normal distributions were used after log-transformation. Statistical analysis was performed using PASW Statistics 17.0 (Statistical Package for Social Science Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The differences of means and prevalence among the groups were analyzed by ANOVA and χ2 test, respectively, and A post hoc analysis was performed with Dunnett's test. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to evaluate the contribution of confounding risk factors (e.g., age, BMI, smoking status, SBP, DBP, antihypertensive medication, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, antilipidemic medication, FPG, antidiabetic medication, and history of CVD) for carotid atherosclerosis. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Background of Subjects

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the 663 male and 916 female subjects. Ages of the enrolled subjects ranged with a mean of 79 ± 8 years (men, 78 ± 8 years; women, 79 ± 8 years; P < 0.001). In men, age, prevalence of antihypertensive medication, and TG showed a gradual increasing trend. In women, age, prevalence of antihypertensive medication, TG and prevalence of Ischemic heart disease showed a gradual increasing trend and HDL-C showed a gradual decrease. The prevalence of MetS also showed a gradual increasing according to the UA quartiles in both genders. There were no inter-group differences in prevalence of alcohol consumption, FPG, prevalence of antidiabetic and antilipidemic medication in both genders.

Carotid atherosclerosis of subjects according to quartile of UA

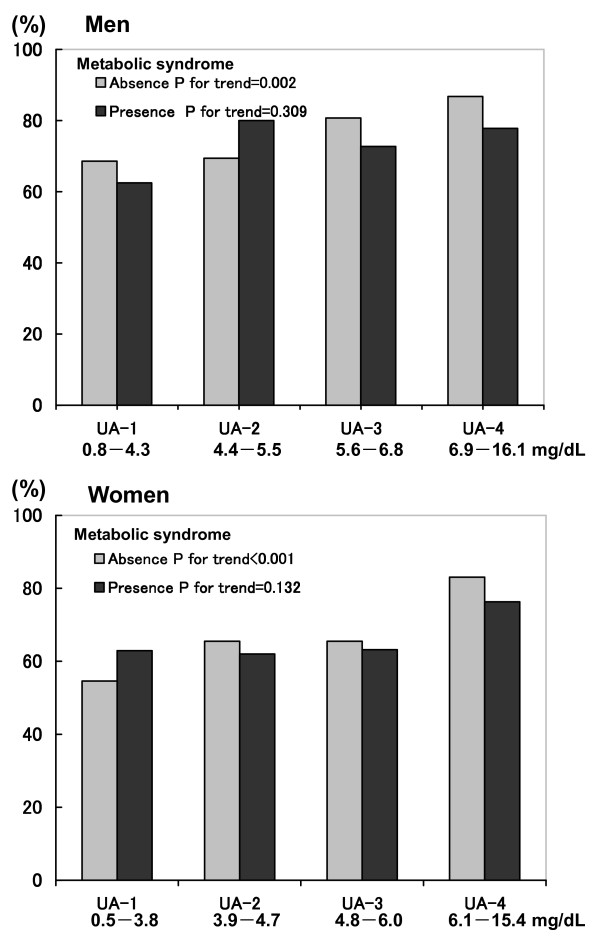

As shown in Table 2, carotid IMT was significantly increased according to the UA quartiles in both genders without MetS and in women with MetS, but was not necessarily increased in men with MetS. As shown in Figure 1, the prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis was significantly increased with increased UA quartile in both genders without MetS.

Table 2.

Carotid intima-media thickness of subjects according to quartile of uric acid and metabolic syndrome by gender

| Quartile of serum uric acid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid range Men (mg/dL) Women(mg/dL) |

UA-1 0.8-4.3 0.5-3.8 |

UA-2 4.4-5.5 3.9-4.7 |

UA-3 5.6-6.8 4.8-6.0 |

UA-4 6.9-16.1 6.1-15.4 |

Pfor trend* |

| All subjects | |||||

| Men, N = 663 | 1.02 ± 0.20 # | 1.06 ± 0.26 | 1.03 ± 0.20 § | 1.13 ± 0.27 | < 0.001 |

| Women, N = 916 | 0.97 ± 0.18 # | 0.98 ± 0.20 # | 0.99 ± 0.19 § | 1.06 ± 0.25 | < 0.001 |

| Subjects without metabolic syndrome (< 3 components of metabolic syndrome) | |||||

| Men, N = 483 | 1.01 ± 0.20 # | 1.07 ± 0.29 | 1.03 ± 0.20 § | 1.15 ± 0.28 | < 0.001 |

| Women, N = 599 | 0.95 ± 0.18 § | 0.97 ± 0.19 † | 0.99 ± 0.20 | 1.04 ± 0.21 | 0.002 |

| Subjects with metabolic syndrome (≥3 components of metabolic syndrome) | |||||

| Men, N = 180 | 1.07 ± 0.23 | 1.04 ± 0.14 | 1.05 ± 0.19 | 1.10 ± 0.24 | 0.487 |

| Women, N = 317 | 1.01 ± 0.18 | 0.99 ± 0.22 † | 1.00 ± 0.19 † | 1.10 ± 0.23 | 0.004 |

† P < 0.05; § P < 0.005; # P < 0.001 vs. the fourth quartile (UA-4). *P-value: ANOVA and Dunnett's test was used for the pos hoc analysis.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis according to quartile of uric acid (UA) and metabolic syndrome by gender. The prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis was also significantly increased with increased UA quartile only in both genders without metabolic syndrome.

Adjusted-odds ratio for carotid atherosclerosis according to quartile of UA and MetS by gender

In Table 3, to examine possible associations between quartiles of UA and the incidence of carotid atherosclerosis after subdivision of the subjects according to MetS status, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed adjusted for age, gender, BMI, smoking status, SBP, DBP, antihypertensive medication, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, antilipidemic medication, FPG, antidiabetic medication, and history of CVD. In men, ORs (95% CI) were significantly increased in the third {1.75 (1.02-3.02)} and fourth quartiles {2.01 (1.12-3.60)} of UA compared with that in the first quartile, and in women the OR was significantly increased only in the fourth quartile {2.10 (1.30-3.39)}. Similarly, the ORs were significantly associated with increasing quartiles of UA in both genders without MetS, but not necessarily increased in those with MetS.

Table 3.

Adjusted-odds ratio (95% CI) for carotid atherosclerosis according to quartile of uric acid and metabolic syndrome by gender

| Quartile of serum uric acid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid range Men (mg/dL) Women (mg/dL) |

UA-1 0.8-4.3 0.5-3.8 |

UA-2 4.4-5.5 3.9-4.7 |

UA-3 5.6-6.8 4.8-6.0 |

UA-4 6.9-16.1 6.1-15.4 |

| All subjects | ||||

| Men, N = 663 | 1 (reference) | 1.06 (0.63-1.76) | 1.75 (1.02-3.02) † | 2.01 (1.12-3.60) † |

| Women, N = 916 | 1 (reference) | 1.44 (0.94-2.21) | 1.29 (0.84-1.98) | 2.10 (1.30-3.39)§ |

| Subjects without metabolic syndrome (< 3 components of metabolic syndrome) | ||||

| Men, N = 483 | 1 (reference) | 0.92 (0.51-1.67) | 2.00 (1.03-3.87) † | 2.54 (1.21-5.34) ‡ |

| Women, N = 599 | 1 (reference) | 1.78 (1.06-3.00)† | 1.41 (0.83-2.40) | 2.54 (1.35-4.78)§ |

| Subjects with metabolic syndrome (≥3 components of metabolic syndrome) | ||||

| Men, N = 180 | 1 (reference) | 2.14 (0.67-6.81) | 1.55 (0.50-4.83) | 2.26 (0.72-7.10) |

| Women, N = 317 | 1 (reference) | 0.81 (0.36-1.79) | 1.12 (0.51-2.49) | 1.43 (0.62-3.27) |

CI, confidential interval. Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, antilipidemic medication, fasting plasma glucose, antidiabetic medication, and history of cardiovascular disease. † P < 0.05; ‡ P < 0.01; § P < 0.005 vs. the first quartile (UA-1).

Adjusted-odds ratio of subgroups for carotid atherosclerosis according to quartile of UA by gender

Next, to control potential confounding factors by age, BMI, history of CVD, and medication, the data were further stratified by their values (Table 4). In men, the ORs for carotid atherosclerosis were significant in subgroups of age ≥75 years, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, no history of CVD, and absence of medication, and in women the ORs were significant in subgroups of age < 75 years, BMI ≥25 kg/m2, regardless of history of CVD, presence of medication.

Table 4.

Adjusted-odds ratio (95% CI) of subgroups for carotid atherosclerosis according to quartile of uric acid by gender

| Men | Women | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid range (mg/dl) Characteristics |

N | UA-1 0.8-4.3 |

UA-2 4.4-5.5 |

UA-3 5.6-6.8 |

UA-4 6.9-16.1 |

P for trend* | N | UA-1 0.5-3.8 |

UA-2 3.9-4.7 |

UA-3 4.8-6.0 |

UA-4 6.1-15.4 |

P for trend* |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| < 75 years | 241 | 1 (reference) | 0.72 (0.33-1.60) | 0.99 (0.46-2.14) | 1.08 (0.44-2.64) | 0.802 | 293 | 1 (reference) | 1.63 (0.80-3.34) | 1.35 (0.65-2.79) | 4.11 (1.61-10.5) § | 0.020 |

| ≥75 years | 422 | 1 (reference) | 1.33 (0.66-2.67) | 2.76 (1.21-6.29) † | 3.00 (1.34-6.70) ‡ | 0.015 | 623 | 1 (reference) | 1.49 (0.85-2.63) | 1.24 (0.71-2.17) | 1.57 (0.87-2.83) | 0.400 |

| Body mass index | ||||||||||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 557 | 1 (reference) | 1.08 (0.62-1.88) | 1.79 (0.98-3.26) | 1.61 (0.86-2.99) | 0.162 | 729 | 1 (reference) | 1.46 (0.90-2.35) | 1.38 (0.85-2.26) | 1.51 (0.88-2.59) | 0.314 |

| ≥25 kg/m2 | 106 | 1 (reference) | 1.54 (0.23-10.3) | 3.17 (0.49-20.4) | 15.1 (1.60-143) † | 0.030 | 187 | 1 (reference) | 1.92 (0.64-5.78) | 1.77 (0.63-4.99) | 8.66 (2.44-30.8) # | 0.001 |

| History of CVD | ||||||||||||

| No | 348 | 1 (reference) | 1.34 (0.72-2.50) | 2.47 (1.26-4.86) ‡ | 2.02 (1.01-4.06) † | 0.037 | 557 | 1 (reference) | 2.00 (1.18-3.37) † | 1.13 (0.68-1.90) | 1.95 (1.10-3.45) † | 0.016 |

| Yes | 315 | 1 (reference) | 0.66 (0.25-1.75) | 0.93 (0.33-2.62) | 1.98 (0.63-6.28) | 0.185 | 359 | 1 (reference) | 0.87 (0.40-1.85) | 1.79 (0.77-4.15) | 2.93 (1.08-7.92) † | 0.037 |

| Medication | ||||||||||||

| No | 279 | 1 (reference) | 1.23 (0.59-2.54) | 2.52 (1.09-5.82) † | 3.71 (1.47-9.35) ‡ | 0.011 | 333 | 1 (reference) | 1.69 (0.84-3.41) | 1.97 (0.93-4.15) | 0.95 (0.41-2.18) | 0.178 |

| Yes | 384 | 1 (reference) | 0.89 (0.41-1.90 | 1.27 (0.60-2.70) | 1.19 (0.54-2.64) | 0.786 | 583 | 1 (reference) | 1.36 (0.77-2.40) | 1.15 (0.66-1.99) | 2.84 (1.52-5.33)§ | 0.004 |

CVD, cardiovascular disease. Medications include antihypertensive, antilipidemic, and antidiabetic medications. Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, antilipidemic medication, fasting plasma glucose, antidiabetic medication, and history of cardiovascular disease. † P < 0.05; ‡ P < 0.01; § P < 0.005; # P < 0.001 vs. the first quartile (UA-1).

Discussion

MetS, representing a cluster of visceral obesity, raised BP, dyslipidemia and glucose intolerance induced by insulin resistance, is a common basis for the development of atherosclerosis, especially CVD [3-5]. In our study, MetS as defined by the modified NCEP-ATP III report criteria was present in 27.1% of men and 34.6% of women. We found 2 results from this cross-sectional data. First, sex-specific UA quartiles are associated with various risk factors and the prevalence of MetS. Second, UA levels might be associated with carotid atherosclerosis independently of other risk factors in both genders without MetS.

Several previous studies have reported possible associations between hyperuricemia and the prevalence of MetS [22-24]. In a prospective study of 8,429 men and 1,260 women aged 20-82 years, 1,120 men and 44 women developed MetS during a mean follow-up of 5.7 years, and men with UA levels ≥6.5 mg/dL had a 1.60-fold increase in risk of MetS (95% CI, 1.34-1.91) as compared with those who had levels < 5.5 mg/dL (P for trend < 0.001), and women with UA levels ≥4.6 mg/dL had a 2.29-fold higher risk of MetS (P for trend = 0.02) [22]. These findings suggest that hyperuricemia may be another component of MetS [24]. We thought that sex-specific analyses were also required because at all ages, the UA level is higher in men than in women [22,23]. We cannot explain the underlying mechanism that accounts for the gender difference from this study. A partial explanation for this result could be alcohol consumption, which is more likely to be higher in men, the use of antihypertensive medications such as diuretics, which are known to increase UA levels [25], and the influence of sex hormones [26]. Furthermore, UA tends to positively associate with FPG in subjects without diabetes and negatively associate with FPG in subjects with diabetes [27]. In our study, the analysis was performed after adjusting for FPG, medication, and alcohol consumption (data not shown), but the results were similar. Effects of alcohol consumption or sex hormone require further investigation in the future.

Hyperuricemia is well recognized as a risk factor for atherosclerotic diseases such as CVD [12,13] and carotid atherosclerosis [28-34]. However, whether UA is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular mortality is still a controversy, as previous studies suggest that UA is associated with other cardiovascular risk factors [8-11] despite the strengths of the associations. In cross-sectional screening data from 8,144 individuals, the prevalence of carotid plaque was significantly higher with increasing quartiles of UA level, in men without MetS but not in men with MetS or in women with or without MetS [32]. On the other hand, in a prospective study of 4,966 men (79% white) and 6,522 women (74% white) who were aged 45 to 64 years at baseline, after adjustment for known risk factors that correlate with UA, the association of UA with B-mode ultrasound carotid IMT became non significant in white women and much weaker and not statistically significant in black women and white men [33]. These conflicting findings are partly related to methodological differences and to participant characteristics. In addition, as UA revels relate with increasing numbers of or special metabolic risk factors, the effect of UA on carotid atherosclerosis might become negligible.

The mechanisms by which UA reflects the risk for carotid atherosclerosis are not completely understood even though previous studies have been done in this area, and it is unclear whether high UA levels promote or protect against the development of CVD, or simply act as a passive marker of increased risk. UA regulates critical proinflammatory pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hyperuricemia might be partially responsible for the proinflammatory endocrine imbalance in the adipose tissue and vascular smooth muscle cells [35,36] which is an underlying mechanism of the low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance in subjects with the MetS, and causes dysfunction of endothelial cells. In addition, experimental evidence suggests that adverse effects of UA on the vasculature have been linked to increased chemokine and cytokine expressions, induction of the renin-angiotensin system, and to increased vascular C-reactive protein (CRP) expression [37]. UA also promotes endothelial dysfunction through inactivation of NO and suppression of the proliferation of endothelial cells [38]. Thus, arteriosclerosis induced by hyperuricemia may be a novel mechanism for the development of MetS and carotid atherosclerosis. However, Nieto et al. demonstrated that the higher UA levels seemed associated with elevated total serum antioxidant capacity among individuals with carotid atherosclerosis and be a powerful free radical scavenger in humans [39]. These antioxidant properties of UA could be expected to offer a number of benefits within the cardiovascular system.

We need to be aware of the limitations in interpreting the present results. First, based on its cross-sectional study design, the present result is inherently limited in its ability to elucidate causal relationships between risk factors and carotid atherosclerosis. Second, since all participants were patients, we could not eliminate the possible effects of underlying diseases (e.g., hypertension and diabetes), alcohol consumption, medication (e.g., diuretics, antihyperuricemic and antilipidemic medications) and FPG on the results. Thus, the analysis was performed after adjusting for confounding factors including FPG and medication (e.g., antihypertensive, antilipidemic, and antidiabetic medication). Third, we used BMI ≥25 kg/m2 to classify individuals with visceral obesity because waist circumference measurements were not available, which might have caused an under or over estimation of the effect of visceral obesity on MetS. In fact, the prevalence of MetS in women was higher than those in men and general reports on Japanese [40]. Moreover, secondary prevention interventions after obesity, raised BP, dyslipidemia and diabetes may be successful in reducing risk factors, thus attenuating the observed association of risk factors with diseases. These points need to be addressed again in prospective population-based studies.

In sum, we reported a significant association between the clustering of cardiovascular risk factors known as MetS and UA, and carotid IMT in subjects with risk factors for atherosclerosis. In both genders that did not have MetS, UA was found to be an independent risk factor for the incidence of carotid atherosclerosis. Serum UA confers an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity, and its identification may thus be important for risk assessment and treatment of patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ST, RK, and MO participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. TK and MA contributed to the acquisition of data and its interpretation. MO conceived of the study, participated in its design, coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Shuzo Takayama, Email: spya6yq9@rhythm.ocn.ne.jp.

Ryuichi Kawamoto, Email: rykawamo@yahoo.co.jp.

Tomo Kusunoki, Email: kusunoki.tomo.mm@ehime-u.ac.jp.

Masanori Abe, Email: masaben@m.ehime-u.ac.jp.

Morikazu Onji, Email: onjimori@m.ehime-u.ac.jp.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Foundation for Development of Community (2011).

References

- National Cholesterol Education Program. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F. American Heart Association; National Heart and Blood Institute: Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Parise H, Sullivan L, Meigs JB. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112:3066–3072. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill AM, Katz R, Girman CJ, Rosamond WD, Wagenknecht LE, Barzilay JI, Tracy RP, Savage PJ, Jackson SA. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease in older people: The cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1317–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo C, Williams K, Hunt KJ, Haffner SM. The National Cholesterol Education Program - Adult Treatment Panel III, International Diabetes Federation, and World Health Organization definitions of the metabolic syndrome as predictors of incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:8–13. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiwaku K, Nogi A, Kitajima K, Anuurad E, Enkhmaa B, Yamasaki M, Kim JM, Kim IS, Lee SK, Oyunsuren T, Yamane Y. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome using the modified ATP III definitions for workers in Japan, Korea and Mongolia. J Occup Health. 2005;47:126–135. doi: 10.1539/joh.47.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So A, Thorens B. Uric acid transport and disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120:1791–1799. doi: 10.1172/JCI42344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y, Hayashi T, Tsumura K, Endo G, Fujii S, Okada K. Serum uric acid and the risk for hypertension and Type 2 diabetes in Japanese men: The Osaka Health Survey. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1209–1215. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milionis HJ, Kakafika AI, Tsouli SG, Athyros VG, Bairaktari ET, Seferiadis KI, Elisaf MS. Effects of statin treatment on uric acid homeostasis in patients with primary hyperlipidemia. Am Heart J. 2004;148:635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Landsberg L, Weiss ST. Uric acid and coronary heart disease risk: evidence for a role of uric acid in the obesity-insulin resistance syndrome. The Normative Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:288–294. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, Strazzullo P, Farinaro E, Trevisan M. Uric acid metabolism and tubular sodium handling. Results from a population-based study. JAMA. 1993;270:354–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510030078038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Alderman MH. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971-1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2000;283:2404–2410. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.18.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi AC, Miname MH, Santos RD. Uric acid: A marker of increased cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata K, Hashimoto T, Ueshima H, Okayama A. NIPPON DATA 80 Research Group. Absence of an association between serum uric acid and mortality from cardiovascular disease: NIPPON DATA 80, 1980-1994. National Integrated Projects for Prospective Observation of Non-communicable Diseases and its Trend in the Aged. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:461–468. doi: 10.1023/A:1013735717961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto R, Tomita H, Oka Y, Ohtsuka N. Relationship between serum uric acid concentration, metabolic syndrome and carotid atherosclerosis. Intern Med. 2006;45:605–614. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald WT, Levy RI. Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen JT, Salonen R. Ultrasonographically assessed carotid morphology and the risk of coronary heart disease. Arter Throm. 1991;11:1245–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.11.5.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu PS, Desai SR. A simple and reproducible method for assessing intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:85–89. doi: 10.1259/bjr.70.829.9059301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati P, Vanuzzo D, Casaroli M, Di Chiara A, De Biasi F, Feruglio GA, Touboul PJ. Prevalence and determinants of carotid atherosclerosis in a general population. Stroke. 2002;23:1705–1711. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.12.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The examination Committee of Criteria for "Obesity Disease" in Japan. Japan Society for Study of Obesity. New criteria for 'obesity disease' in Japan. Circ J. 2002;66:987–992. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota T, Takamura T, Hirai N, Kobayashi K. Preobesity in World Health Organization classification involves the metabolic syndrome in Japanese. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1252–1253. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X, Church TS, Meriwether RA, Lobelo F, Blair SN. Uric acid and the development of metabolic syndrome in women and men. Metabolism. 2008;57:845–852. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou WK, Wang MH, Huang DH, Chiu HT, Lee YJ, Lin JD. The relationship between serum uric acid level and metabolic syndrome: differences by sex and age in Taiwanese. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:219–224. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsouli SG, Liberopoulos EN, Mikhailidis DP, Athyros VG, Elisaf MS. Elevated serum uric acid levels in metabolic syndrome: an active component or an innocent bystander? Metabolism. 2006;55:1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage PJ, Pressel SL, Curb JD, Schron EB, Applegate WB, Black HR, Cohen J, Davis BR, Frost P, Smith W, Gonzalez N, Guthrie GP, Oberman A, Rutan G, Probstfield JL, Stamler J. Influence of long-term, low-dose, diuretic-based, antihypertensive therapy on glucose, lipid, uric acid, and potassium levels in older men and women with isolated systolic hypertension: The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:741–751. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T, Kannel WB. Drinking and its relation to smoking, BP, blood lipids, and uric acid. The Framingham study. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1366–1374. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1983.00350070086016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan H, Dong Y, Gao W, Tuomilehto J, Qiao Q. Diabetes associated with a low serum uric acid level in a general Chinese population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;76:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neogi T, Ellison RC, Hunt S, Terkeltaub R, Felson DT, Zhang Y. Serum uric acid is associated with carotid plaques: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:378–384. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Yang Z, Lu B, Wen J, Ye Z, Chen L, He M, Tao X, Zhang W, Huang Y, Zhang Z, Qu S, Hu R. Serum uric acid level and its association with metabolic syndrome and carotid atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2011;10:72. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-72. Aug 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavil Y, Kaya MG, Oktar SO, Sen N, Okyay K, Yazici HU, Cengel A. Uric acid level and its association with carotid intima-media thickness in patients with hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalcini T, Gorgone G, Gazzaruso C, Sesti G, Perticone F, Pujia A. Relation between serum uric acid and carotid intima-media thickness in healthy postmenopausal women. Intern Emerg Med. 2007;2:19–23. doi: 10.1007/s11739-007-0004-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Toda E, Nagai R, Yamakado M. Association between serum uric acid, metabolic syndrome, and carotid atherosclerosis in Japanese individuals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1038–1044. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000161274.87407.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren C, Folsom AR, Eckfeldt JH, McGovern PG, Nieto FJ. Correlates of uric acid and its association with asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis: the ARIC Study. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:331–340. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00052-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan WH, Bai CH, Chen JR, Chiu HC. Associations between carotid atherosclerosis and high factor VIII -activity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Stroke. 1997;28:88–94. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.28.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellis J, Watanabe S, Li JH, Kang DH, Li P, Nakagawa T, Wamsley A, Sheikh-Hamad D, Lan HY, Feng L, Johnson RJ. Uric Acid Stimulates Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Production in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Via Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Cyclooxygenase-2. Hypertension. 2003;41:1287–1293. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000072820.07472.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin WMS, Marek G, Wymer D, Pannu V, Baylis C, Johnson RJ, Sautin YY. Hyperuricemia as a Mediator of the Proinflammatory Endocrine Imbalance in the Adipose Tissue in a Murine Model of the Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes. 2011;60:1258–1269. doi: 10.2337/db10-0916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellis J, Kang DH. Uric acid as a mediator of endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and vascular disease. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Lozada LG, Nakagawa T, Kang DH, Feig DI, Franco M, Johnson RJ, Herrera-Acosta J. Hormonal and cytokine effects of uric acid. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:30–33. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000199010.33929.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto FJ, Iribarren C, Gross MD, Comstock GW, Cutler RG. Uric acid and serum antioxidant capacity: a reaction to atherosclerosis? Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:131–139. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda E, Kawai R. Reproducibility of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein as an inflammatory component of metabolic syndrome in Japanese. Circ J. 2010;74:1488–1493. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]