Abstract

In the present study, Cd2+ adsorption on polyacrylate-coated TiO2 engineered nanoparticles (TiO2-ENs) and its effect on the bioavailability as well as toxicity of Cd2+ to a green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii were investigated. TiO2-ENs could be well dispersed in the experimental medium and their pHpzc is approximately 2. There was a quick adsorption of Cd2+ on TiO2-ENs and a steady state was reached within 30 min. A pseudo-first order kinetics was found for the time-related changes in the amount of Cd2+ complexed with TiO2-ENs. At equilibrium, Cd2+ adsorption followed the Langmuir isotherm with the maximum binding capacity 31.9, 177.1, and 242.2 mg/g when the TiO2-EN concentration was 1, 10, and 100 mg/l, respectively. On the other hand, Cd2+ toxicity was alleviated in the presence of TiO2-ENs. Algal growth was less suppressed in treatments with comparable total Cd2+ concentration but more TiO2-ENs. However, such toxicity difference disappeared and all the data points could be fitted to a single Logistic dose-response curve when cell growth inhibition was plotted against the free Cd2+ concentration. No detectable amount of TiO2-ENs was found to be associated with the algal cells. Therefore, TiO2-ENs could reduce the free Cd2+ concentration in the toxicity media, which further lowered its bioavailability and toxicity to C. reinhardtii.

Introduction

Engineered nanoparticles (ENs), defined as man-made materials smaller than 100 nm in at least two dimensions, are widely recognized as having versatile applications in a variety of areas [1]. However, the novel properties ENs possess may not necessarily be benign. Their potentially adverse effects have been intensively investigated in recent years [2]–[4]. The toxicity of ENs was found to be determined by several physicochemical parameters like particle size, shape, aggregation status, surface coating, chemical composition and so on [3]. Although examining the toxicity of ENs alone could give us invaluable information about the environmental and health risks of nanomaterials, they are actually present in the real world together with other pollutants, which necessitates our understanding about the combined effects of ENs and other toxicants. Colloids are substances with the size range (1–1000 nm) much wider than that of ENs (1–100 nm). They have been reported to be able to facilitate the contaminant transport in the environment (so-called ‘Colloidal Pump’) [5], [6] and further influence their bioavailability in a colloid, pollutant, and organism species specific manner [7], [8]. However, it remains largely unknown how ENs may interact with other pollutants already existing in the environment and how these interactions may influence the behavior, fate, and toxicity of each other.

Up till now there is still limited research about the effects of ENs on the bioavailability of other pollutants with contradictory results reported. Park et al. [9] found no accumulation of 17α-ethinylestradiol associated with nC60 aggregates in the zebrafish Danio rerio through dietary exposure. In contrast, TiO2-ENs could enhance the toxicity of tributyltin to abalone embryos possibly as a result of tributyltin adsorption onto TiO2-ENs followed by internalization into the embryos [10]. Similarly, the toxicity of various metals like Cd2+, Cu2+, As (V) was found to increase in the presence of either TiO2-ENs or carbon nanotubes [11]–[14]. However, the synergistic toxicity of TiO2-ENs and As (V) on Ceriodaphnia dubia was either aggravated or eliminated as determined by EN to metal ratio [15]. Pollutant-specific effects were also observed for the influences of C60 aggregates on the toxicity of atrazine, methylparathion, pentachlorophenol, and phenanthrene [16].

To further explore how ENs may influence the bioavailability of other pollutants, we investigated Cd2+ adsorption kinetics and equilibrium isotherm on polyacrylate-coated TiO2-ENs. Its bioaccumulation and toxicity in the freshwater green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii with and without TiO2-ENs were compared. Potential accumulation (including surface adsorption and internalization) of TiO2-ENs in the algal cells was also examined. TiO2-ENs were chosen because of their wide applications in various products like sunscreens, cosmetics, paints, and surface coatings [10]. There were 50,400 tons of TiO2-ENs produced in 2010, representing 0.7% of the overall TiO2 market. Their production is projected to further increase to 201,500 tons by 2015 [17]. Meanwhile, TiO2-ENs are relatively inert with negligible dissolution and have no remarkable effects on C. reinhardtii based on the results of our preliminary experiment. This would simplify the later explanation of the toxicity results. In addition, TiO2-ENs were used in most researches on the interactions between ENs and other pollutants, which make the comparison of our study with the literature possible. As bare TiO2-ENs without any surface coating are easy to form aggregates in aqueous solution [14], a surface-coated substitute with similar photochemical properties was applied to ensure the effects we observed came from the nano-sized (<100 nm) dispersions. The overall objective was thus to reveal the underlying mechanisms how TiO2-ENs may affect the bioavailability and toxicity of Cd2+ and to answer the question whether Cd2+ toxicity in the presence of TiO2-ENs could still be predicted with the classical Free Ion Activity Model (FIAM), in which the metal toxicity is determined by its free ion concentration in the ambient environment [18].

Materials and Methods

Phytoplankton culture conditions and TiO2-EN characterization

The axenic culture of the Chlorophyta Chlamydomonas reinhardtii used was originally obtained from the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan. The algal cells were maintained in an artificial freshwater WC medium [19]. Its pH was kept at 7.5±0.1 by 5 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS). The temperature was 25°C with a light illumination of 50 µmol photons/m2/s in a 12∶12 Light-Dark cycle.

TiO2-ENs (anatase) in powder form were purchased from Vivo Nano (Toronto, Canada). Their primary particle size was approximately 1–10 nm as reported by the manufacturer. They were coated with hydrophilic sodium polyacrylate (ca. 74% of the total EN weight) and thus could be well dispersed in water. The TiO2-EN suspension in the base adsorption or toxicity medium below was further examined through a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEM-200CX from JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) to ensure their good dispersibility as described by Miao et al. [20]. Fast freeze-drying method was adopted to eliminate the EN aggregation during the sample preparation. A dynamic light scattering particle sizer (DLS, ZetaPALS from Brookhaven Instruments, NY, USA) was also applied to determine the hydrodynamic diameter of TiO2-ENs and their surface charge.

Kinetics and equilibrium isotherm study of Cd2+ adsorption by TiO2-ENs

A modified WC medium (WCm) was used as the base solution of all adsorption experiments (Table S1). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 11.7 µM) in the normal WC medium was excluded given that it is a strong metal binding ligand and could remarkably reduce Cd2+ adsorption. Accordingly, the trace metal nutrient concentrations were turned down to avoid their unnecessary precipitation (e.g., Fe3+) or toxicity (e.g., Cu2+). There were five TiO2-EN concentration treatments (1.0, 3.0, 10.0. 30.0, and 100.0 mg/l TiO2-ENs) in duplicate for the kinetics experiment. The total Cd2+ concentration was fixed at 1 mg/l. Each replicate had 20 ml adsorption medium in a 50 ml polypropylene centrifuge tube, which had been pre-equilibrated with solutions of the same composition as those in the following experiment to minimize the Cd2+ loss on the tube wall. The whole experiment lasted for 6 h with 7 time points (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2 and 6 h). At each time point, 0.2 ml aliquot from each replicate was filtered through a 10 kilo Dalton (kD) ultracentrifuge with pore size approximately 1 nm (PALL Nanosep series). Both the ultrafiltrate and what was retained on the membrane were then digested in 1 ml ultrapure concentrated HNO3 under 60°C for at least 4 d. They were further diluted with Milli-Q water (18.2 MΩ) to 7% w/v before the Cd2+ concentrations were determined by a Thermo M6 atomic absorption spectrophotometer equipped with a GF95Z graphite furnace system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The total Cd2+ concentration in the adsorption media without ultrafiltration was also measured at the beginning and end of the experiment for mass balance calculation.

As for the equilibrium isotherm experiment, the variation of Cd2+ adsorption with its ambient concentration (nominal total Cd2+ concentration - 0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, and 10.0 mg/l) was examined in the presence of 1, 10, and 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs, respectively. Since Cd2+ adsorption got saturated when its concentration approached 0.3 mg/l with 1 mg/l TiO2-ENs, the two highest Cd2+ concentrations (3.0 and 10.0 mg/l) were not used for this EN concentration treatment. The whole procedure was similar to that of the adsorption kinetics experiment above. Based on the results of the kinetics study, Cd2+ adsorption got equilibrated within 30 min. The duration of the equilibrium isotherm experiment was thus shortened to 4 h and Cd2+ distribution in different fractions was measured only at the end of this experiment. A control experiment with the same concentrations of Cd2+ but no TiO2-ENs was also conducted to examine the possibility of Cd2+ precipitation at different concentrations.

Effects of TiO2-ENs on Cd2+ toxicity

Three toxicity tests in total were performed to investigate how TiO2-ENs may affect the bioavailability and toxicity of Cd2+ to C. reinhardtii. WCm also served as the base of the toxicity media. There were seven Cd2+ concentration treatments (nominal total Cd2+ concentration - 0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0, and 3.0 mg/l) in duplicate with and without 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs, respectively, for two of the three toxicity tests. However, the nominal total Cd2+ concentration was fixed at 1 mg/l and various concentrations (0, 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 mg/l) of TiO2-ENs were applied in the third one. Major differences between the three toxicity tests were shown in Table S2. The polycarbonate bottles and other containers to be used in the toxicity tests were pre-equilibrated with the corresponding toxicity media similar to what was performed in the adsorption experiment above. All the toxicity media were made one day in advance and left overnight under the same conditions as the following experiment for equilibration. Their pH was kept at 7.5±0.1.

The algal cells were first acclimated in WCm without Cd2+ or TiO2-ENs until arriving at the mid-exponential growth phase. They were then collected by centrifugation at 1700 RCF, rinsed twice with 15 ml fresh WCm and resuspended into the toxicity media. Right before the addition of algal cells, 0.2 ml aliquot from each medium replicate was filtered through a 10 kD membrane. The total Cd2+ concentration in the ultrafiltrate (non-adsorbed Cd2+) was measured, based on which the free Cd2+ concentration ([Cd2+]F) of each toxicity medium was calculated using the MINEQL+ software package (Version 4.5 from Environmental Research Software, Hallowell, ME, USA) with updated thermodynamic constants and the influence of ionic strength calibrated. The whole experiment lasted for 2 d with three time points (0, 1st, and 2nd d). At each time point, the cell density was measured by a Z2 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter Inc., CA, USA). The cell specific growth rate μ was calculated as described by Miao et al. [21]. At the end of each toxicity test, 10 ml aliquot from each replicate was filtered through a 1.2 µm polycarbonate membrane (Millipore). Cd2+ weakly adsorbed on the cell surface ([Cd2+]cell-ads) was removed after soaking the cells in 10 ml EDTA (100 µM) for 3 min. The algal cells retained on the membrane were further digested with concentrated HNO3 and [Cd2+]intra was thus obtained. Meanwhile, the Cd2+ concentrations in the <1.2 µm filtrate, in the <10 kD fraction, and in the 1 ml aliquot without any filtration were measured for mass balance calculation.

To further examine the potential bioaccumulation of TiO2-ENs in the algal cells, another 10 ml aliquot was filtered through a 1.2 µm polycarbonate membrane, rinsed twice with 15 ml fresh WCm and then combusted in muffle furnace at 460°C for 2 h. The residue was digested in a mixture of 0.4 g (NH4)2SO4 and 1.0 ml H2SO4 at 250°C for half an hour. After being diluted to 2.5% w/v by Milli-Q water, the Ti concentration was determined by GFAAS. Controls containing the same concentrations of TiO2-ENs and Cd2+ but no C. reinhardtii were applied to eliminate any interference from the TiO2-EN aggregates retained by the 1.2 µm polycarbonate membrane. The background Ti concentration in the cells not exposed to TiO2-ENs was also measured.

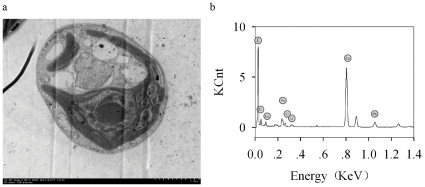

TEM images of algal cells exposed to 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs but without any addition of Cd2+ were then taken to visually examine the interactions between TiO2-ENs and C. reinhardtii. The sample preparation was similar to our previous study [20]. Briefly, 100 ml algal culture was centrifuged and fixed with 4% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 4 h. After the cells were cleaned with phosphate buffer (0.3 M, pH = 7.3), they were stained in 1% (mg/ml, weight to volume ratio) osmium tetroxide for 2 h, and then dehydrated with 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90% and 100% acetone solution sequentially. Afterwards, they were embedded into epoxy resin (Epon 812, DDSA, MNA and DMP-30), sectioned at 100 nm thickness, further stained with uranyl acetate (5 g in 50 ml ethanol) and lead citrate (1.33 g in 30 ml H2O). The elemental composition of the interesting spots on the TEM images was investigated with an energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrometer.

Statistical analysis

Any ‘significant’ difference (accepted at p<0.05) was based on results of one-way or two-way analysis of variance with post-hoc multiple comparisons (Turkey or Tamhane) (SPSS 11.0 by SPSS, Chicago, USA). The normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests) and homogeneity of variance (Levene's test) of the data were both examined when performing the analysis of variance.

Results and Discussion

Adsorption of Cd2+ by TiO2-ENs

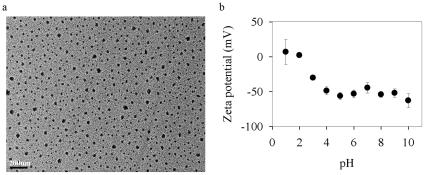

The TiO2-ENs used in the present study were coated with sodium polyacrylate and could thus be well dispersed in WCm as supported by their TEM images shown in Fig. 1a. Their diameter was 46.6 nm on average by measuring 1000 particles randomly chosen from the copper grids, which was consistent with what was obtained by DLS (19.0–46.8 nm). The relatively good dispersibility of TiO2-ENs coated by the polyelectrolyte could be explained by their much lower pHpzc (Fig. 1b), at which a particle surface has zero net electrical charge, than that of their naked counterpart (pHpzc = 2 vs. 6) [22], [23]. Such decrease in pHpzc was mainly caused by polyacrylate's ability to push the slip plane of the crystal lattice away from the ENs, change their charge distribution in the diffusion layer and block the active sites on the TiO2-EN surface as well [23]. Furthermore, the extent of the shift in pHpzc was determined by both the concentration and molecular weight of polyacrylates. Despite their good dispersibility in WCm, the actual diameter of TiO2-ENs was much bigger than what was reported by the manufacturer (1–10 nm) suggesting the electric double layer of the primary nanoparticles was compressed in the adsorption medium with the ionic strength 2.65×10−3 M and aggregates were thus formed. The presence of divalent cations like Ca2+ (0.25 mM) and Mg2+ (0.15 mM) in WCm could further destabilize the TiO2-EN suspension [1].

Figure 1. The transmission electron microscope image of TiO2-ENs dispersed in the modified WC medium (WCm) (a) and their zeta potentials (mV) at different pH (b).

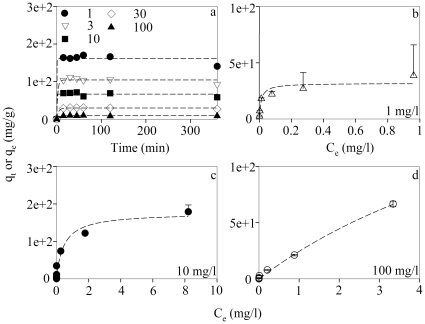

In both adsorption kinetics and equilibrium isotherm experiments, the concentrations of Cd2+ retained on the 10 kD membrane (TiO2-EN surface-adsorbed) and in the filtrate (non-adsorbed) were compared with what was measured without filtration. A good mass balance (100±10%) was achieved for most treatments. Cd2+ was found to quickly adsorb onto TiO2-ENs and a steady state was reached within 30 min (Fig. 2a). Rapid association of Cd2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Pb2+ and Zn2+ with TiO2-ENs was also observed by Engates and Shipley [24] and most adsorption was completed in 5 min. Meanwhile, higher proportions of Cd2+ were adsorbed in higher TiO2-EN concentration treatments unless no Cd2+ in the medium was available any more when the concentration of TiO2-ENs exceeded 30 mg/l. Accordingly, 0.16, 0.33, 0.70, 0.90, and 0.93 mg/l Cd2+ was adsorbed by 1, 3, 10, 30, 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs, respectively, after 30 min. Such trend looked reversed in Fig. 2a as the adsorption was normalized to the TiO2-EN concentration (mg/g). Additionally, the possibility whether Cd2+ with concentration up to 1 mg/l was over-saturated in WCm, precipitated out and thus made the Cd2+ adsorption results overestimated was also investigated. A negligible amount (less than 1%) was retained on the 10 kD membrane without any addition of TiO2-ENs at the end of the 6-h experiment suggesting that all the Cd2+ was in soluble form for the kinetics experiment. Although EDTA was not used in WCm, no significant precipitates were formed when preparing this medium.

Figure 2. Adsorption of Cd2+ (qt, mg/g) on TiO2-ENs in the kinetics (a) and 4-h equilibrium isotherm (b–d) experiments, respectively.

There were five treatments with different concentrations of TiO2-ENs (1.0, 3.0, 10.0. 30.0, and 100.0 mg/l) but the same concentration of total Cd2+ (1 mg/l) in the kinetics experiment. Various concentrations of Cd2+ (0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, and 10.0 mg/l initially) were used in each equilibrium isotherm experiment with different TiO2-EN concentrations (b–d: 1, 10, 100 mg/l, respectively). Since Cd2+ adsorption got saturated when its concentration approached 0.3 mg/l with 1 mg/l TiO2-ENs, the two highest Cd2+ concentrations (3.0 and 10.0 mg/l) were not used for this EN concentration treatment. Dashed lines represent the simulated curves of Cd2+ adsorption kinetics and equilibrium isotherm by the pseudo-first order (a) and Langmuir (b–d) models. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 2).

The Cd2+ adsorption kinetics results were then fitted with the pseudo-first order equation as follows,

| (1) |

Where qt and qe are the Cd2+ adsorption (mg/g) at time t (min) and at equilibrium, respectively. k (min−1) represents the equilibrium rate constant of the pseudo-first order adsorption. Values of the different parameters thus obtained were listed in Table 1. The adsorption of Cd2+ onto TiO2-ENs and Cu2+ onto Fe3O4 magnetic ENs were also found to comply with the pseudo-first order model in previous studies [22], [25]. Values of k were 0.15–0.25 min−1 for Cd2+ and 0.64–1.05 min−1 for Cu2+, which were of the same order of magnitude as what was found (0.23–2.35 min−1) in the present study even though the TiO2-ENs used here were coated with sodium polyacrylate. Fitting the adsorption kinetics data points by the pseudo-second order model was also tried with unsatisfied results (data not shown), possibly due to the high Cd2+ concentrations we used considering that the choice of models is dependent on the solute concentration [26].

Table 1. Values of the different parameters obtained when simulating the kinetics and equilibrium isotherm of Cd2+ adsorption by TiO2-ENs with the pseudo-first order and Langmuir models, respectively.

| Pseudo-first order | Langmuir | ||||||

| qe | k | r2 | p | qm | Ka | r2 | p |

| 160.9±12.1 | 2.35±0.35 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 31.9±17.2 | 83.5±49.6 | 0.88 | 0.0053 |

| 104.1±2.90 | 0.39±0.05 | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 177.1±77.4 | 2.14±1.12 | 0.94 | <0.0001 |

| 66.1±1.32 | 3.21±0.48 | 0.96 | <0.0001 | 242.2±23.9 | 0.113±0.04 | 0.99 | <0.0001 |

| 29.2±0.63 | 0.25±0.01 | 0.99 | <0.0001 | ||||

| 8.51±0.30 | 0.23±0.03 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | ||||

In the equilibrium isotherm experiment, a biphasic correlation between the TiO2-EN normalized Cd2+ adsorption (qe, mg/g) and the non-adsorbed Cd2+ concentration in the medium (Ce, mg/l) was found for each of the three TiO2-EN concentration treatments (1, 10, and 100 mg/l) (Fig. 2b–d). Namely, qe went up proportionally with Ce first, slowed down thereafter and even plateaued at high Cd2+ levels especially when 1 or 10 mg/l TiO2-ENs were used. In the meantime, the potential difference in the proportions of Cd2+ adsorbed by different concentrations of TiO2-ENs was small or negligible when the initial concentration of Cd2+ was too low to saturate the ENs. However, the difference got more and more significant as Cd2+ adsorption approached the saturation point. When 3 µg/l Cd2+ was applied, most of it (91.7–97.3%) was adsorbed in all the three TiO2-EN concentration treatments. As the initial Cd2+ concentration increased further to 0.01 and 1 mg/l, the proportion of Cd2+ complexed with 1 mg/l TiO2-ENs decreased to 71.8% and 9.02%. However, nearly all Cd2+ (96.4–100%) could still be adsorbed on 10 and 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs. It was not until the initial Cd2+ concentration exceeded 1 mg/l that significant difference (p<0.05) between the 10 and 100 mg/l TiO2-EN concentration treatments appeared with 17.9% and 66.6% adsorption when the initial Cd2+ concentration was 10 mg/l. The concentration of Cd2+ retained on the 10 kD membrane in the control treatments having the same concentrations of Cd2+ but no TiO2-ENs was also negligible as compared with those adsorbed by the ENs. It further implies that Cd2+ precipitation was insignificant for all the concentration treatments of the present study as was in contrast to what was estimated by MINEQL+ based on an equilibrium assumption.

The biphasic correlation between qe and Ce was then fitted to the Langmuir isotherm for each of the three TiO2-EN concentration treatments as follows,

| (2) |

Where Ka is the Langmuir constant (l/mg) related to adsorption energy and qm represents the maximal monolayer adsorption capacity (mg/g). A good correlation was found with values for the various parameters shown in Table 1 suggesting a monolayer adsorption of Cd2+ on TiO2-ENs.

Cd2+ adsorption on TiO2-ENs with different crystal size (7.72–145 nm) was previously investigated [27]. Values of qm thus derived from the Langmuir isotherm were in the range of 3.93–56.0 mg/g with lower adsorption by bigger particles. Much smaller difference was observed when qm was normalized to the surface area of TiO2-ENs (0.29–0.39 mg/m2). As the TiO2-ENs we used were made up of a TiO2 core (4.23 g/cm3) coated with sodium polyacrylate (1.22 g/cm3), its density and specific surface area were estimated to be approximately 1.50 g/cm3 and 85.8 m2/g. However, the surface area normalized qm (0.37–2.82 mg/m2) we obtained was still higher than what was reported by Gao et al. [27], especially for the two higher TiO2-EN concentration treatments. It suggests that the polyacrylate surface coating could improve the metal ion adsorption ability of the ENs. Cd2+ was able to form bidentate and monodentate ligand complex with polyacrylic acid [28], which may also be the same case for its adsorption on the polyacrylate-coated TiO2-ENs. Given that sodium polyacrylate accounts for 74% of the TiO2-ENs we used, the Cd2+ to –COOH ratio at saturation would be 0.036, 0.20, and 0.27, respectively, when the concentration of TiO2-ENs was 1, 10, and 100 mg/l. It implies that part of the carboxylate group from polyacrylate was bound with TiO2 or other cations (e.g., Ca2+ and Mg2+ etc.) in the adsorption medium and was thus not available to Cd2+. The possibility that the EN surface was heterogeneous and some of the Cd2+ may be complexed with the TiO2 core itself further complicated the metal-EN interactions [27].

Cd2+ toxicity as affected by TiO2-ENs

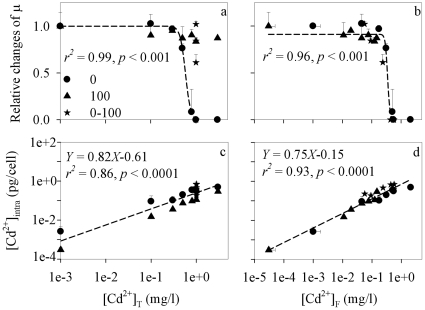

The growth of C. reinhardtii in WCm (no addition of Cd2+) with or without 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs was compared in our preliminary experiment. No obvious growth inhibition was found, which simplified our exploration how TiO2-ENs may affect the bioavailability and toxicity of metal ions. The toxicity of bare TiO2-ENs to various phytoplankton was investigated in the literature [29]. The median effect concentration EC50 thus obtained ranged over a few orders of magnitude (e.g., 5.83–241 mg/l) as the toxicity of ENs was dependent on parameters like particle size, shape, chemical composition and so on. Surface coatings may further eliminate the toxicity of ENs [30]. The initial and final Cd2+ concentrations in the <10 kD fraction of each replicate for the three toxicity tests were both measured. The decrease in [Cd2+]F with exposure time was within 30% for most treatments. The relative changes of μ were thus plotted against either total dissolved Cd2+ concentration ([Cd2+]T, including what was adsorbed on TiO2-ENs) or [Cd2+]F (Fig. 3a, b) at the beginning of each toxicity test to determine which metal ion concentration could predict its toxicity better in the presence of TiO2-ENs. As expected, μ was substantially reduced at high Cd2+ levels when no TiO2-ENs was applied. A typical dose-response correlation between the relative changes of μ and either type of Cd2+ concentration was observed. Namely, the cell growth was kept constant in the first three lowest Cd2+ concentration treatments. It was then strikingly inhibited with more than 90% reduction when [Cd2+]T ([Cd2+]F) increased to 0.8 (0.50) mg/l and completely ceased thereafter.

Figure 3. Relative changes of the cell specific growth rate (μ) (a–b) and intracellular Cd2+ concentration ([Cd2+]intra, pg/cell) (c–d) with either the total dissolved ([Cd2+]T, mg/l) (a, c) or free Cd2+ ([Cd2+]F, mg/l) concentrations (b, d) at the beginning of the three toxicity experiments where 0, 100, and 1–100 mg/l TiO2-ENs were applied, respectively.

Dashed lines represent the simulated curves for the relative changes of μ (a–b) and [Cd2+]intra (c–d) at different [Cd2+]T (a, c) and [Cd2+]F (b, d) by the Logistic dose-response and Freundlich models, respectively. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 2).

However, when 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs were applied to the different treatments with [Cd2+]T comparable to those of the first toxicity test above, the adverse effects of Cd2+ were substantially alleviated. There was a growth inhibition of only 13% in the highest concentration treatment with [Cd2+]T 3 mg/l, which in contrast was lethal to the cells if no TiO2-ENs were added. Similarly, μ went down from 0.46 d−1, as was comparable to that in the control without any addition of TiO2-ENs and Cd2+, to zero when [Cd2+]T was fixed at 1 mg/l but the TiO2-EN concentration decreased from 100 to 0 mg/l in the third experiment. However, growth inhibition to different extent at similar [Cd2+]T but different concentrations of TiO2-ENs, as shown in Fig. 3a, disappeared when the relative changes of μ were plotted against [Cd2+]F. All the data points from the different toxicity tests could be well fitted to a single Logistic dose-response curve (y = min+(max−min)/(1+(x/EC50)Hillslope)) (Fig. 3b). The [Cd2+]F-based EC50 thus obtained was 0.35±0.03 mg/l which was similar to 0.46 mg/l observed in our previous study [31] and was within the range of values (0.03–2.41 mg/l) reported in the literature [32], [33]. As the cell growth was differently inhibited at similar [Cd2+]T but various concentrations of TiO2-ENs, only the dose-related responses of the first toxicity test without any addition of TiO2-ENs were simulated with the Logistic model in Fig. 3a.

Of the limited research on the interactions between ENs and trace metals, TiO2-ENs were frequently chosen which made the comparison of our study with the literature possible. The bioaccumulation of Cd2+ and As (V) in carp was found to increase remarkably in the presence of TiO2-ENs, as was explained by ENs' ability to facilitate the metal transport through the gills (dissolved uptake) and to induce the metal assimilation in the intestines (dietary assimilation) when EN-contaminated foods were fed to the fish [34], [35]. Additionally, the enhanced oxidation of metal ions in reduced form like As (III) by TiO2-ENs as a photocatalyst especially under the light condition could further accelerate the metal uptake [34]. As a result, the trace metal toxicity was aggravated even though part of them were still associated with TiO2-ENs in the organisms [12]. On the other hand, metal toxicity to unicellular organisms may decline abruptly in the presence of TiO2-ENs if the metal-EN complexes thus formed cannot penetrate the cell membrane. The bare TiO2-ENs used by Hartmann et al. [14] were able to reduce the Cd2+ toxicity to a green alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata but the toxicity inhibition was greater than what could be explained by the concentration of Cd2+ not associated with TiO2-ENs, suggesting a possible carrier effect, or mixture toxic effects of TiO2-ENs and Cd2+. The latter possibility was more likely as considering the toxicity of TiO2-ENs on the alga itself (EC50 = 71.1–241 mg/l) and any direct evidence of EN internalization was lacking.

To further examine the underlying mechanisms how Cd2+ toxicity was lessened by the polyacrylate-coated TiO2-ENs, the bioaccumulation of Cd2+ ([Cd2+]cell-ads and [Cd2+]intra) was quantified at the end of each toxicity test. Their changes with [Cd2+]T as well as [Cd2+]F were shown in Fig. 3c, d and S1. Overall, there was a positive correlation between Cd2+ accumulation and [Cd2+]T or [Cd2+]F. When [Cd2+]F went up from 3.05×10−5 to 2.10 mg/l, [Cd2+]intra was enhanced by three orders of magnitude (Fig. 3d). The cellular Cd2+ concentration in the same strain of alga was found to increase approximately from 0.025 pg/cell when [Cd2+]F was 5.39×10−3 mg/l to 0.25 pg/cell with [Cd2+]F 3.37 mg/l [33], as was comparable to what was observed in the present study. On the other hand, [Cd2+]intra was strikingly different in treatments containing the same [Cd2+]T but various concentrations of TiO2-ENs. It was decreased by 40–88% in all treatments when 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs were applied in the second toxicity test as compared with those in the first one (Fig. 3c). Similarly, a negative correlation between [Cd2+]intra and TiO2-EN concentration was observed with fixed [Cd2+]T in the third toxicity experiment.

More importantly, the difference between [Cd2+]intra at similar [Cd2+]T but distinct concentrations of TiO2-ENs was substantially diminished when [Cd2+]intra was plotted against [Cd2+]F instead of [Cd2+]T (Fig. 3d). Such trend was more obvious when all the data points from the three toxicity tests were fitted to a single Freundlich isotherm below for each diagram (Fig. 3c, d and S1).

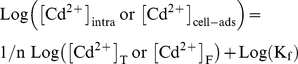

|

(3) |

Where Kf represents the Freundlich constant and n is a dimensionless parameter related to the metal binding affinity. A better correlation between [Cd2+]intra and [Cd2+]F than that between [Cd2+]intra and [Cd2+]T (r2 = 0.93 vs. 0.86) was observed. It suggests that Cd2+ toxicity alleviation by TiO2-ENs was mainly caused by the decrease in [Cd2+]F as a result of surface adsorption. In contrast, there was an unsatisfied correlation (r2 = 0.68 vs. 0.62) between [Cd2+]cell-ads and [Cd2+]T or [Cd2+]F (Fig. S1). At similar [Cd2+]F, higher Cd2+ adsorption was usually found when TiO2-ENs were applied. Therefore, a certain amount of TiO2-ENs might be associated with the algal cells or just highly aggregated in the medium and were retained by the 1.2 µm polycarbonate membrane. Cd2+ adsorbed on these ENs could also be removed by EDTA, and thus made [Cd2+]cell-ads overestimated.

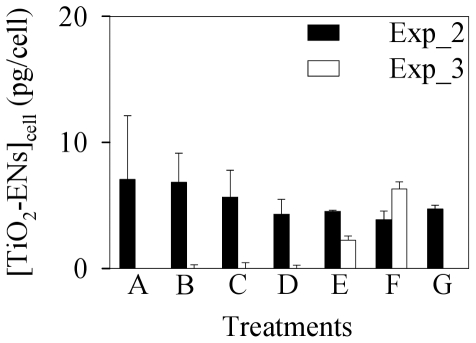

Potential TiO2-EN accumulation (including both cell surface adsorbed and intracellular accumulated ones) by C. reinhardtii was then quantified with GFAAS. As shown in Fig. 4, the bioaccumulated concentration of TiO2-ENs ([TiO2-ENs]cell) was in the range of 3.85–7.06 pg/cell for the second toxicity experiment in the presence of 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs. Although [TiO2-ENs]cell decreased slightly with the enhancement of [Cd2+]T, it was statistically insignificant (p>0.05). Additionally, a substantial accumulation of TiO2-ENs was only detected in the two highest TiO2-EN concentration treatments (30 and 100 mg/l) for the third toxicity test. Given that TiO2-ENs had a diameter of 46.6 nm on average, there should be 4.8×104–8.9×104 particles associated with a single algal cell as equivalent to approximately 1000 particles within each cell slice (100 nm thick) mounted on the TEM copper grid when 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs were applied. However, no TiO2-ENs were found either inside the cells or adsorbed on the cell surface after several cell slices were investigated with suspicious spots scanned by the EDX spectrometer (Fig. 5). It implies that most of the Ti signal determined by GFAAS might come from the additional TiO2-EN aggregates intercepted by the 1.2 µm membrane in the presence of C. reinhardtii, which cannot be subtracted with the control treatments containing the same concentrations of Cd2+ and TiO2-ENs but no algal cells. TiO2-ENs can attach to various algal species. The green alga P. subcapitata could even carry TiO2-ENs with weight 2.3 times higher than their own on the cell surface [14], [36], [37]. The adsorption of TiO2-ENs was found to be dependent on the pH of the medium and maximum adsorption was observed at pH = 5.5 (comparable to the pHpzc of bare TiO2-ENs) [38]. It implies that electrostatic attraction played a critical role in the interactions between TiO2-ENs and algal cells. As the pHpzc of TiO2-ENs we used is around 2, their surface was negatively charged in WCm (pH = 7.5) the same as that of the algal cells themselves. Therefore, a negligible amount of TiO2-ENs would be expected to be associated with C. reinhardtii unless other forces such as hydrogen bonding overrides the electrostatic and steric repulsion between the cells and ENs as observed by Schwab et al. [39]. The lack of direct contact between polyacrylate-coated TiO2-ENs might be another reason why they were less toxic than bare TiO2-ENs.

Figure 4. Accumulation of TiO2-ENs ([TiO2-ENs]cell, pg/cell) by Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in the different treatments of the second (Exp_2) and third (Exp_3) toxicity experiments.

In Exp_2, treatment A–G indicates different initial concentrations of Cd2+ (0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0, and 3.0 mg/l) with the TiO2-EN concentration fixed at 100 mg/l. In Exp_3, the initial Cd2+ concentration was fixed at 1 mg/l and various concentrations (0, 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 mg/l) TiO2-ENs were used for treatments A–F. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 2).

Figure 5. A representative transmission electron microscope (TEM) image (a) and the elemental composition of the interesting spots on it (b), as investigated with an energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrometer, for a cell slice of C. reinhardtii exposed to 100 mg/l TiO2-ENs but without any addition of Cd2+.

Overall, the TiO2-ENs used in the present study could adsorb Cd2+ rather quickly with the maximum adsorption capacity ranging from 31.9 to 242.2 mg/g. The electrostatic and potentially steric repulsions between TiO2-ENs and algal cells could hinder their direct contact with each other, thus prevent the internalization of TiO2-ENs into the cells. The toxicity of Cd2+ was alleviated considerably when TiO2-ENs were applied, as Cd2+ adsorption on the ENs decreased its free ion concentration in the toxicity medium and further its bioaccumulation in the algal cells. However, the Cd2+ toxicity in the presence of TiO2-ENs could still be well predicted with the classical FIAM model.

Supporting Information

Relative changes of the cell surface adsorbed Cd2+ concentration ([Cd2+]cell-ads, pg/cell) with either the total dissolved ([Cd2+]T, mg/l) (a) or free Cd2+ ([Cd2+]F, mg/l) concentrations (b) at the beginning of the three toxicity experiments where 0, 100, and 1–100 mg/l TiO2-ENs were applied, respectively. Dashed lines represent the simulated curves of [Cd2+]cell-ads at different [Cd2+]T (a) and [Cd2+]F (b) by the Freundlich isotherm model. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 2).

(TIF)

Compounds and their concentrations in the modified WC medium used in the present study.

(DOC)

Composition of the toxicity media for the three experiments.

(DOC)

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The financial support offered by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41001338) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK2010371) to AJM have made this work possible. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 2.Klaine SJ, Alvarez PJJ, Batley GE, Fernandes TF, Handy RD, et al. Nanomaterials in the environment: Behavior, fate, bioavailability, and effects. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008;27:1825–1851. doi: 10.1897/08-090.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science. 2006;311:622–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1114397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberdorster G, Oberdorster E, Oberdorster J. Nanotoxicology: An emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:823–839. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jonge LW, Kjaergaard C, Moldrup P. Colloids and colloid-facilitated transport of contaminants in soils: An introduction. Vadose Zone J. 2004;3:321–325. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honeyman BD. Geochemistry - Colloidal culprits in contamination. Nature. 1999;397:23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen M, Wang WX. Bioavailability of natural colloid-bound iron to marine plankton: Influences of colloidal size and aging. Limnol Oceanogr. 2001;46:1956–1967. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan JF, Wang WX. Influences of dissolved and colloidal organic carbon on the uptake of Ag, Cd, and Cr by the marine mussel Perna viridis. Environ Pollut. 2004;129:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park J-W, Henry TB, Menn F-M, Compton RN, Sayler G. No bioavailability of 17 alpha-ethinylestradiol when associated with nC(60) aggregates during dietary exposure in adult male zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere. 2010;81:1227–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X, Zhou J, Cai Z. TiO(2) Nanoparticles in the marine environment: Impact on the toxicity of tributyltin to abalone (Haliotis diversicolor supertexta) embryos. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:3753–3758. doi: 10.1021/es103779h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun H, Zhang X, Niu Q, Chen Y, Crittenden JC. Enhanced accumulation of arsenate in carp in the presence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2007;178:245–254. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan W, Cui M, Liu H, Wang C, Shi Z, et al. Nano-TiO(2) enhances the toxicity of copper in natural water to Daphnia magna. Environ Pollut. 2011;159:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KT, Klaine SJ, Lin S, Ke PC, Kim SD. Acute toxicity of a mixture of copper and single-walled carbon nanotubes to Daphnia magna. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2010;29:122–126. doi: 10.1002/etc.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartmann NB, Von der Kammer F, Hofmann T, Baalousha M, Ottofuelling S, et al. Algal testing of titanium dioxide nanoparticles-Testing considerations, inhibitory effects and modification of cadmium bioavailability. Toxicol. 2010;269:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D, Hu J, Irons DR, Wang J. Synergistic toxic effect of nano-TiO(2) and As(V) on Ceriodaphnia dubia. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409:1351–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baun A, Sorensen SN, Rasmussen RF, Hartmann NB, Koch CB. Toxicity and bioaccumulation of xenobiotic organic compounds in the presence of aqueous suspensions of aggregates of nano-C-60. Aquat Toxicol. 2008;86:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Future Markets Inc. The world market for nanoparticle titanium dioxide. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell PGC. Interactions between trace metals and aquatic organisms: A critique of the free-ion activity model. In: Tessier A, Turner D, editors. Metal speciation and bioavailability in aquatic systems. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillard R. Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrate. In: Smith W, Chanley M, editors. Culture of marine invertebrate animals. New York: Plenum; 1975. pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao AJ, Luo Z, Chen CS, Chin WC, Santschi PH, et al. Intracellular uptake: A possible mechanism for silver engineered nanoparticle toxicity to a freshwater alga Ochromonas danica. Plos One. 2010;5(12):e15196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miao AJ, Wang WX, Juneau P. Comparison of Cd, Cu, and Zn toxic effects on four marine phytoplankton by pulse-amplitude-modulated fluorometry. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2005;24:2603–2611. doi: 10.1897/05-009r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Debnath S, Ghosh UC. Equilibrium modeling of single and binary adsorption of Cd(II) and Cu(II) onto agglomerated nano structured titanium(IV) oxide. Desalin. 2011;273:330–342. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liufu SC, Mao HN, Li YP. Adsorption of poly(acrylic acid) onto the surface of titanium dioxide and the colloidal stability of aqueous suspension. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;281:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engates KE, Shipley HJ. Adsorption of Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn, and Ni to titanium dioxide nanoparticles: effect of particle size, solid concentration, and exhaustion. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2011;18:386–395. doi: 10.1007/s11356-010-0382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hao YM, Chen M, Hu ZB. Effective removal of Cu (II) ions from aqueous solution by amino-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. J Hazard Mater. 2010;184:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azizian S. Kinetic models of sorption: a theoretical analysis. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;276:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao Y, Wahi R, Kan AT, Falkner JC, Colvin VL, et al. Adsorption of cadmium on anatase nanoparticles-effect of crystal size and pH. Langmuir. 2004;20:9585–9593. doi: 10.1021/la049334i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyajima T, Mori M, Ishiguro S, Chung KH, Moon CH. On the complexation of Cd(II) ions with polyacrylic acid. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1996;184:279–288. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1996.0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menard A, Drobne D, Jemec A. Ecotoxicity of nanosized TiO(2). Review of in vivo data. Environ Pollut. 2011;159:677–684. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derfus AM, Chan WCW, Bhatia SN. Probing the cytotoxicity of semiconductor quantum dots. Nano Lett. 2004;4:11–18. doi: 10.1021/nl0347334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang NX, Zhang XY, Wu J, Xiao L, Yin Y, et al. Effects of microcystin-LR on the metal bioaccumulation and toxicity in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Water Res. 2012;46:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavoie M, Le Faucheur S, Fortin C, Campbell PGC. Cadmium detoxification strategies in two phytoplankton species: Metal binding by newly synthesized thiolated peptides and metal sequestration in granules. Aquat Toxicol. 2009;92:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang W-X, Dei RCH. Metal stoichiometry in predicting Cd and Cu toxicity to a freshwater green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Environ Pollut. 2006;142:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun HW, Zhang XZ, Zhang ZY, Chen YS, Crittenden JC. Influence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on speciation and bioavailability of arsenite. Environ Pollut. 2009;157:1165–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Sun H, Zhang Z, Niu Q, Chen Y, et al. Enhanced bioaccumulation of cadmium in carp in the presence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Chemosphere. 2007;67:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadiq IM, Dalai S, Chandrasekaran N, Mukherjee A. Ecotoxicity study of titania (TiO(2)) NPs on two microalgae species: Scenedesmus sp. and Chlorella sp. . Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2011;74:1180–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang C, Cha D, Ismat S. Progress report: short-term chronic toxicity of photocatalytic nanoparticles to bacteria, algae, and zooplankton. 2005. EPA Grant Number: R831721. Available: http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.abstractDetail/abstract/7384/report/2005. Accessed 2012 Jan 31.

- 38.Aruoja V, Dubourguier H-C, Kasemets K, Kahru A. Toxicity of nanoparticles of CuO, ZnO and TiO(2) to microalgae Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:1461–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwab F, Bucheli TD, Lukhele LP, Magrez A, Nowack B, et al. Are carbon nanotube effects on green algae caused by shading and agglomeration? Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:6136–6144. doi: 10.1021/es200506b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Relative changes of the cell surface adsorbed Cd2+ concentration ([Cd2+]cell-ads, pg/cell) with either the total dissolved ([Cd2+]T, mg/l) (a) or free Cd2+ ([Cd2+]F, mg/l) concentrations (b) at the beginning of the three toxicity experiments where 0, 100, and 1–100 mg/l TiO2-ENs were applied, respectively. Dashed lines represent the simulated curves of [Cd2+]cell-ads at different [Cd2+]T (a) and [Cd2+]F (b) by the Freundlich isotherm model. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 2).

(TIF)

Compounds and their concentrations in the modified WC medium used in the present study.

(DOC)

Composition of the toxicity media for the three experiments.

(DOC)