Abstract

Background

Public reporting of patient health outcomes offers the potential to incentivize quality improvement by fostering increased accountability among providers. Voluntary reporting of risk-adjusted outcomes in cardiac surgery, for example, is viewed as a “watershed event” in healthcare accountability. However, public reporting of outcomes, cost, and quality information in orthopaedic surgery remains limited by comparison, attributable in part to the lack of standard assessment methods and metrics, provider fear of inadequate adjustment of health outcomes for patient characteristics (risk adjustment), and historically weak market demand for this type of information.

Questions/purposes

We review the origins of public reporting of outcomes in surgical care, identify existing initiatives specific to orthopaedics, outline the challenges and opportunities, and propose recommendations for public reporting of orthopaedic outcomes.

Methods

We performed a comprehensive review of the literature through a bibliographic search of MEDLINE and Google Scholar databases from January 1990 to December 2010 to identify articles related to public reporting of surgical outcomes.

Results

Orthopaedic-specific quality reporting efforts include the early FDA adverse event reporting MedWatch program and the involvement of surgeons in the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative. Issues that require more work include balancing different stakeholder perspectives on quality reporting measures and methods, defining accountability and attribution for outcomes, and appropriately risk-adjusting outcomes.

Conclusions

Given the current limitations associated with public reporting of quality and cost in orthopaedic surgery, valuable contributions can be made in developing specialty-specific evidence-based performance measures. We believe through leadership and involvement in policy formulation and development, orthopaedic surgeons are best equipped to accurately and comprehensively inform the quality reporting process and its application to improve the delivery and outcomes of orthopaedic care.

Introduction

Improving the value of health care, defined as health outcomes per dollar spent, is a theme that has long been pursued and often prioritized, and yet difficult to achieve in the United States, mostly as a result of diverging definitions of value, misaligned incentives, and conflicting priorities that exist among healthcare stakeholders. Many of the changes in US healthcare delivery that have occurred over the past few decades have produced limited improvement in value [25, 34]. Experts have suggested that improvement in value within a cost-constrained, quality-seeking healthcare structure will require a complete redesign of the current fragmented and inefficient healthcare delivery infrastructure with a shift in emphasis from containing costs to improving quality [35]. Of the many principles that could contribute to this shift and redesign, public reporting of outcomes based on valid performance measures and incentivized by reimbursements are ones that are gaining growing interest and investment of resources. Public reporting of hospital mortality rates in Medicare surgical patients dates back to the Health Care Financing Administration’s (HCFA’s) efforts to record and report hospital mortality in the 1980s [4]; however, most of these efforts have relied upon process and administrative data related to provision of surgical care. The difficult yet essential measurement of health-related outcomes data has yet to be substantially achieved, reported, or aligned with provider reimbursement. A number of issues have consistently plagued past and recent efforts to gather and report information on the cost, quality, and value of health care. These include data accuracy and attributions, case mix and risk adjustment, sample size, validity, reliability, and clinical relevance.

Central to the goal of improving value in the delivery of musculoskeletal care is the collection and public reporting of cost and quality information in orthopaedic surgery. Dissemination of this information would presumably contribute to correcting the information asymmetry (where one party has better information or superior knowledge than the other) in healthcare markets [19], which has thus far resulted in a “quality blind” payment system that incentivizes larger volume and intensity of services without formal consideration for the quality of outcomes. Public reporting is viewed as a necessary building block in the pursuit of value-based health care that more formally considers quality in the assessment of value achieved [15].

The policy goals of reporting quality and cost information in orthopaedic surgery are to equip stakeholders, including healthcare providers, purchasers, payers, and patients, with information to evaluate the relative value of musculoskeletal care. Correlating surgical outcomes with the costs associated with the delivery of surgical care holds the potential of yielding the measure of value desired. Implicit in these efforts is the need to benchmark surgeon and hospital performance with both individual and composite measures. Predictably, prior studies have documented the difficulty and complexity of developing physician-level performance profiles that meet adequate validity and reliability standards. Mehrotra et al. [30] demonstrated that reliable attribution of costs to the individual physician is very difficult to achieve. In evaluating the reliability of individual and composite quality measures used in benchmarking physician performance, Scholle et al. [42] found that in typical health plan administrative data, most physicians had inadequate numbers of quality events to support reliable quality measurement. Currently the literature on public reporting is limited and fragmented.

This review therefore serves to highlight and summarize the breadth and the current limitations of public reporting in orthopaedic surgical care. We focus on identifying areas that require expertise and input from orthopaedic surgeons in surveying, reporting, and implementing quality performance measurement while proposing general guidelines for public reporting of cost and quality information related to musculoskeletal care. We review the origins of public reporting on cost and quality in surgical care, identify existing public reporting initiatives and those specific to orthopaedics, outline the challenges and opportunities associated with public reporting of quality measures and performance, and propose recommendations for how orthopaedic physician-level reporting could be used to improve the quality of care.

Search Strategy and Criteria

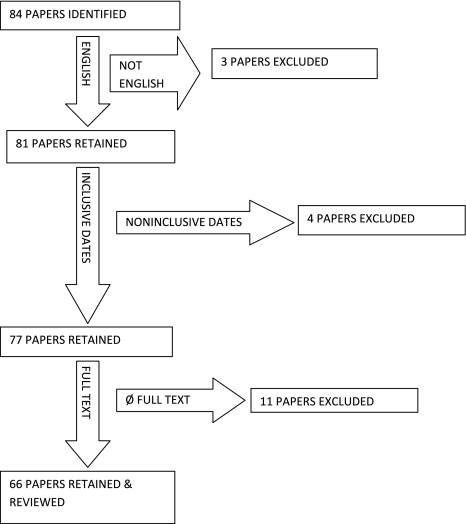

A review of the literature was performed through a bibliographic search of MEDLINE databases using “(Quality Improvement OR Quality Indicators) AND Public Reporting AND (Physician OR Orthopaedics).” The articles retrieved were limited to English language with links to the full text and dates ranging from January 1990 to December 2010. The search was supplemented by a review of the references included in selected articles and a review of the related citations presented during the electronic MEDLINE search. Using selected search terms (Table 1; Fig. 1), the search was extended to a global review of public and private quality measurement and reporting programs, including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Two of us (YM, CAB) independently reviewed each abstract and the full article content of 66 articles. We excluded most of the 66 publications as unrelated to cost and quality in orthopaedics. Three of the articles from this group of 66 were selected based on their relevance to orthopaedics. These three articles were supplemented by an exhaustive review of the references contained in several of the 66 articles, which yielded an additional 39 relevant manuscripts (YM, CAB, KJB).

Table 1.

Categories and examples of performance measures used in public reporting programs

| Measures | Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | Use of an EMR | Easy to measure | Limited correlation with quality of care or outcomes |

| Nurse/patient ratio | Rarely actionable | ||

| Process | Use of perioperative antibiotics | Easy to measure | Limited clinical relevance |

| Surgical site marking | Evidence-based | Limited correlation with quality of care or outcomes | |

| Postoperative VTE prophylaxis | Guide manageable change | ||

| Outcome | Health-related quality of life | Most relevant measure of quality | Difficult to measure |

| Infection rate | Time-intensive, expensive | ||

| Dislocation rate | Require risk adjustment | ||

| Readmission rate | Time lag between intervention and outcome make real-time reporting impossible | ||

| Reoperation rate | Reflection of cumulative impact of multiple processes so isolation of variable to change is often difficult | ||

| Patient experience | Patient satisfaction, experience surveys | Patient-centered | Dependent on patient expectations and sociodemographic characteristics |

| Measurable | Dependent on alternatives | ||

| May not correlate with quality of care or clinical outcomes | |||

| Influenced by multiple processes so isolation of variable to change is often difficult | |||

| Efficiency | Episode of care costs | Easy to measure | Standards are not well established |

| Use of surgical services | Comparative across practices | Require risk adjustment | |

| Use of injections, physical therapy | No correlation with quality of care, patient outcomes, or cost-effectiveness |

Modified and reprinted from Bozic KJ, Smith AR, Mauerhan DR, Pay-for-performance in orthopedics: implications for clinical practice, Pages 8–12, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier. EMR = Electronic Medical Record; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Fig. 1.

The search strategy and criteria are shown.

History of Public Reporting of Cost and Quality Information

A number of different metrics, including structural, process, outcome, patient experience, and efficiency, can be used to measure and report healthcare provider performance (Table 1). Structural measures refer to measures of provider infrastructure such as nursing-to-bed ratios, the availability of an intensive care unit and emergency services, and the use of an electronic health record. Structural measures have the advantage of being easy to measure and difficult to manipulate but are often not readily introduced or used by providers. The most commonly used performance measures currently reported are process measures such as the administration of prophylactic antibiotics before surgery and the use of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis after major surgical procedures [7, 39]. Process measures offer the benefit of being relatively easy to measure in addition to providing valuable feedback to physicians on their compliance with evidence-based practice guidelines. Process measures, however, are surrogate measures that may or may not correlate with clinical outcomes of interest (eg, infection or VTE after TJA, surgical site marking) [6–8]. Outcome measures are generally believed to be the most direct measure of quality [8]. However, clinically relevant outcomes are limited by the fact that they are often difficult to define and measure through the use of administrative claims data (particularly in orthopaedics), require sophisticated risk adjustment tools, and are generally preceded by a long lag period between the introduction of treatment (eg, TJA) and the collection of valid risk-adjusted data on the outcome of interest (eg, revision surgery). Patient experience measures such as Press-Ganey scores [8] are attractive because they are patient-centered but are often criticized because they are highly subjective and dependent on a patient’s expectations and their understanding of the available treatment alternatives [6]. Finally, using management of rotator cuff tears as an example, efficiency measures such as use of imaging and physical therapy services and episode of care costs are relatively easy to measure but are often poorly correlated with quality, lack well-established standards, and require risk adjustment for valid comparison [1, 5, 32]. Several published papers have identified a primary concern among physicians that efficiency measures are being increasingly used as a simple method for payers to “cost-profile” providers with no direct correlation to quality of care [8, 15, 17, 32].

The HCFA’s efforts to record and report hospital mortality data was an early display of outcomes-based reporting [18]. Both hospital- and surgeon-specific risk-adjusted mortality rates after coronary bypass graft surgery (CABG) were reported in several states, including New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey beginning in 1992 [20]. CABG mortality rates in New York declined 41% from 3.52 to 2.78 between 1989 and 1992 after the release of the CABG provider report cards and were labeled a success of the CABG public reporting program [20]. However, the negative unintended consequences that became apparent in cardiac surgeons’ denial of care for severely ill (high-risk) patients, including increased reluctance by 63% of cardiac surgeons to operate on high-risk patients [47] as a means to avoid unfavorable outcomes and low ratings, led to the ultimate disengagement of the program. Through these initial efforts much was learned about the challenges that accompany quality reporting programs, some of which have been addressed and many that still remain.

Orthopaedic-specific Quality Reporting Efforts

Historically, the prioritization of orthopaedic-specific quality reporting efforts have been limited [6–8], because until recently, orthopaedics has not been a target for health plans and purchasers in search of strategies to address escalating costs while enhancing quality. Nevertheless, there were early attempts at public reporting of adverse events in orthopaedics facilitated by the FDA MedWatch program instituted in 1993 [31]. The program continues to facilitate the reporting of all device failures and adverse events by providing specific tools to assist surgeons in the reporting process. The goals of this program have been to encourage surgeons to apply their expertise in understanding the relationships between devices and mechanisms of failure in a manner that informs the manufacturing and use of the product [31]. More recently, such orthopaedic-specific quality reporting efforts have been appended with an amplified focus and investment of resources [27]. These recent quality reporting efforts can partially be attributed to the increased use of costly orthopaedic interventions, which, coupled with the variations in quality and resource use, have predictably generated heightened scrutiny of orthopaedic interventions among the payer (both government and private) and purchaser community [28]. This intensified surveillance has positively translated into research advancements in orthopaedic quality measurement and reporting.

Bozic and Chiu [6] emphasized the need for evidence-based measures in public reporting that focused on quality measurement, and public reporting in TJA. They assessed differences in practice patterns among orthopaedic surgeons and determined whether the use of payer-defined guidelines was correlated with improved outcomes and lower costs. They generally found major variations both in adherence to guidelines and in clinical outcomes and costs associated with TKA and THA, but further noted that even where observed, adherence to existing nonevidence based payer-defined practice guidelines was not associated with improved outcomes or lower costs. The study highlighted the need for investments in defining orthopaedic-specific evidence-based performance measures for use in public reporting as well as the need to incentivize adherence to these guidelines by surgeons. Further efforts to identify causes of variation in care quality, and in poor outcomes associated with error, have recently been undertaken by the Patient Safety Committee of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) [49]. The committee administered and published findings of a member survey directed at identifying trends in orthopaedic errors to help target quality improvement efforts. They reported that the highest frequencies of errors were observed in equipment (29%) and communication (24.7%) errors, and the greatest potential harm was induced by medication errors (9.7%) and wrong-site surgery (5.6%). This effort set an example for collecting and reporting quality data that can be used to better define target areas for research.

Existing Programs and Initiatives

Through a continued effort to assume a more direct and active role in quality measurement and reporting, orthopaedic surgeons have jointly contributed to updating the musculoskeletal-specific measures defined by the National Quality Forum and the CMS-sponsored Physicians Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) recently renamed the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). Such measures include administration of perioperative antibiotics, VTE prophylaxis, aftercare for patients who have osteoporotic fractures, management of back pain, adoption and use of electronic health records (EHRs), and e-prescribing as well as other measures less specific to orthopaedic care. The PQRS is a voluntary reporting program that creates structured channels for eligible providers to report data on quality measures, and furthermore rewards their participation through incentive payments for satisfactorily reporting on the PQRS measures specific to their practice. The initiative was launched through the 2006 Tax Relief and Health Care Act, which called for the establishment of a physician quality reporting system and has evolved into a comprehensive list of measures across many performance categories and specialties [37]. To enroll and participate in the program, providers may report results through use of claims information, through a qualified registry, through the Group Practice Reporting Option (GPRO) or Electronic Health Records as well as a separate Electronic Prescribing (eRx) Incentive Program. There are 194 measures in the 2011 PQRS with four group measures for back pain and perioperative care specific to orthopaedics [36].

Plans for publicly reporting the outcome measures included in the PQRS program are set forth in Section 10331 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. The Act requires CMS to establish a “Physician Compare” Web site that provides information on Medicare-enrolled physicians as well as individual providers participating in the PQRS. This is to be followed with plans to make information on physician performance publicly available in 2012, including measures collected through the PQRS [13]. Other initiatives led by CMS include The Value Based Purchasing (VBP) Program [12], which was established to meet objectives for improving care provided by hospitals and for providing quality information to consumers and other healthcare stakeholders. Under this program, CMS will make value-based incentive payments to acute care hospitals based on the performance and/or improvement of certain quality measures. Other entities that have enriched the development of public reporting guidelines and recommendations include the Institute of Medicine (IOM) with specific guidelines in its “Performance Measurement-accelerating Improvement” 2005 consensus report, the first in a series that provides a comprehensive review of existing measures and outlines an algorithm for analyzing these measures against the six healthcare system goals the Institute has defined, including safety, effectiveness, efficiency, patient-centeredness, timeliness, and equity [23]. The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) [33], a private not-for-profit organization focused on evaluating and reporting on the quality of managed care plans, has also contributed to the development of public reporting guidelines through its Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), a tool used by health plans to measure performance on several dimensions of care as well through its report cards on health plans as well as physician and hospital quality. The Commonwealth Fund [14], which is a working group of experts and leaders representing all sectors of health care as well as academia, professional societies, the business sector, and state and federal entities that is tasked with devising strategies for a high-performing healthcare system with regard to quality, efficiency, and effectiveness, is also involved in developing public reporting guidelines through its Commission on High Performance Health Systems. The Commission has conducted research on the strategies and challenges associated with expanding the availability of publicly reported quality and price information. The American Medical Association [2] has also actively participated in quality reporting activities by taking an active role in designing the CMS Physician Compare Web site, developing a position statement on the Public Release of Information About Quality of Health Care [3].

In addition to the extensive public reporting of health plan measures, hospitals have invested in developing reports on patient experience through the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey (HCAHPS) [21], which was designed by AHRQ, included in HEDIS, and established to provide a standard measurement method of patient experiences with hospital care.

The HCAHPS survey is an instrument and data collection methodology for measuring patients’ perceptions of their hospital experience. It is a set of 27 standardized questions developed and validated by the CMS in 2006 that was created to gather information about inpatient care experience allowing patients, payers, and providers an objective evaluation and comparison of care being delivered by physicians, nurses, and hospitals. Hospitals have also focused on recording and reporting case volumes, mistakes, and near misses and are held accountable for reporting to CMS through the Reporting Hospital Quality Data for Annual Payment Update (RHQDAPU) program with the failure to report on quality indicators resulting in Medicare reimbursement reductions [11]. Other performance reports have been developed and published by organizations such as HealthGrades® [22] and Leapfrog [29], which are designed to provide information on the cost and quality of care provided by physicians and hospitals as well as on the educational background, board certification status, and disciplinary actions placed on physicians. The performance evaluation process implemented by these two organizations entails the voluntary submission of hospital data to the Leapfrog group, which is then analyzed through a HealthGrades® algorithm that assigns individual star ratings based on clinical quality performance and patient satisfaction.

Provider-ranking methodologies are an additional tool that national health plans have developed. In efforts to control costs, purchasers continue to experiment with a variety of approaches to ranking provider performance [41]. Based on research that suggests physician adoption of less intensive practice patterns would decrease healthcare spending [44], purchasers have placed the focus of new payment methodologies on physicians.

These methodologies include analyses of physicians’ use of services and classification systems for comparing which physicians have lower relative costs. On identifying the “high-performance” (ie, higher quality, lower cost) physicians, purchasers then offer patients differential copayments to steer patients to higher performing providers (also known as benefit design), pay bonuses to physicians with lower than average resource use patterns (also referred to as performance-based incentive payments) [45], and publicly report the relative resource use of physicians [16]. These methods were developed under the assumption that measures of performance based on quality and costs can be accurately accessed through claims data and can be made publicly available to inform enrollees. Various benefit designs (eg, differential copayments) have been used by payers and purchasers to incentivize patients to seek high-performing physicians with the expectation that patient volume would shift to those physicians while encouraging lower-performing providers to improve the quality of care delivered. However, according to a recent study [43], the current methods used to tier physicians based on quality performance and cost efficiency exhibited low consistency and revealed geographic and demographic biases that were not accounted for in the methods of physician tiering. These findings point to the many questions and challenges that remain for defining and structuring healthcare performance, cost transparency, and reporting. These include the difficulties in balancing different stakeholder perspectives on performance reporting measures and methodologies, in defining accountability and attribution for outcomes reported, in establishing specialty-specific criteria, and in appropriately risk-adjusting outcomes. These issues are critical as the choice of performance measures and methods of collection will ultimately determine the effectiveness, use, and provider support for implementing a robust performance measurement system [6, 8, 10, 14].

Discussion

The goals of improving the value of healthcare services by enhancing the accuracy and appropriateness of measurement standards, and by publicly reporting these outcome and process measures to increase provider accountability and incentivize performance improvement, hold both promise and challenge. Although the goal for increased transparency and accountability in our healthcare system could lead to improved provider and organizational performance, it must be supported by well-defined outcome measures specific to the specialty evaluated. This is necessary to avoid reporting inaccurate outcomes that unfairly misrepresent physician performance or unjustly label them as low-quality performers. In addition, although the public reporting of outcomes can incentivize improvement in the quality of care delivered, it must be weighed against the potential unintended consequence of incentivizing the denial of care for high-risk patients that could adversely affect reported performance scores and provider reputations.

As evidenced by the challenges associated with physician-ranking methodologies, several micro- and macrolevel complexities and limitations continue to impact the efforts of participants and sponsors of quality reporting [38]. Current methods of measuring performance are considerably limited by the scarcity of available data sources beyond administrative claim information, and by the limited capacity of administrative claims data to accurately reflect the clinical record. This was highlighted in a study that assessed the validity of using administrative claims data in TJA outcomes research [7]. The authors found that although the use of International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes related to revision TJA procedures allowed for the use of administrative databases to evaluate TJA outcomes, some ICD-9 diagnosis codes were accurate in reflecting the clinical record, whereas others were not. Furthermore, they found that when compared with diagnosis codes, TJA-specific ICD-9 procedure codes had poor correlation with the clinical record. The inconsistencies in correlations drawn from the studies highlight the need to exercise discretion when using administrative claims data to define and interpret outcomes [7].

The limitations of administrative data for measuring provider and healthcare organization performance highlight the need for a performance measurement system that is established to evaluate clinical outcomes rather than maintain a record of claims and procedures. For orthopaedics, this system would be comprised of a standard set of metrics based on reliable, stable, and clinically relevant quality measures for benchmarking performance at the provider and healthcare organization level. This standard set of metrics would also include the development and use of comparative effectiveness research results for musculoskeletal care, the identification of methods necessary for risk-adjusting the data to achieve fair comparisons as well as the formulation of strategies to tailor and disseminate reports to specific target audiences. Efforts to create a standard set of reportable metrics for orthopaedics have highlighted the difficulties in collecting data that is accurate [7], and that effectively ensures both appropriate attribution of beneficiaries to providers, and accurate assignment of costs among providers [46]. These efforts have also highlighted the challenges associated with creating readily usable performance measures that can be applied toward improving practice [8]. One study that sought to assess the credibility and applicability of existing public reports of hospital and physician quality found there were more reports of hospital performance than of physician performance, and limited applicability of physician quality reports as a result of insufficient data on clinical quality measures, cost, and efficiency measures as well as patient experience reports, thus limiting the assessment of physician quality of care [9]. This emphasizes the need to develop provider-specific performance measures and explains some of the limitations associated with small sample sizes in current physician reporting, as these sample sizes are generally insufficient to construct valid and reliable reports [27]. The limited applicability of reports based on small sample sizes is increased by individual payer attempts to measure and report physician-level performance, since even high-volume physicians may have only performed a low volume of procedures on patients with any given health plan. Potential solutions to this particular challenge include the pooling of health plan data across time and different plans to increase the likelihood of reliably monitoring specialists [9]. This includes projects such as The Better Quality Information to Improve Care for Medicare Beneficiaries (BQI) Project, a CMS-funded project to test methods of aggregating Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial claims data to calculate and report quality measures for physician groups and individual physicians [9]. Other solutions include the use of consensus-based performance measures and compatible electronic health records across different health plans. The steps required to achieve sufficient volume and accurate attribution are made more difficult by the existing team-based structures of healthcare delivery. It is challenging (and perhaps inappropriate with a risk of undermining team function) to report individual provider concerns about variation in patient risk at the individual provider level, as well as limited data for appropriate risk adjustment at this level and a small patient sample size render it difficult to ensure that a physician’s practice profile primarily reflects their individual performance [46]. For example, Scholle et al. [42] have reported that results based on the denominator of patients for a single physician are performance metrics or to implement the use of episode-based cost payment with physician attribution allotted if x% of a physician’s own costs is in the profile.

The absence of local, regional, and national collaboration on quality reporting initiatives among providers, employers, health plans, and consumers will certainly lead to substantial redundancy, inefficiency, and frustration among the entities seeking participation in quality reporting efforts. There is currently limited compatibility between the information technology systems that measure cost, quality, and reimbursement and this is complicated by the inconsistencies posed by varying levels of stakeholder accountability in current team-based models of care. Long-standing cultural, political, technical, and economic challenges may be more important than the scientific or intellectual barriers to creating and reporting quality measures and costs. These include physicians’ belief that quality is too nebulous to measure and report accurately, purchasers’ skepticism that feedback on performance will lead to changes in provider behavior, and the technical details and expense of acquiring, processing, and communicating data. An example of when feedback on performance has led to changes in provider behavior is displayed in the Intermountain Healthcare System. Rather than attempting to control physicians’ behavior by obligating change based on feedback, the Intermountain Healthcare System of clinical processes displays a method of incentivizing providers to improve care and amend behaviors in response to valid process and outcome data. This is supplemented by the creation of clinical management teams and by a shared culture of professional values centered on patient needs and high-quality care. Intermountain’s clinical management structure is centered around part-time physician-leaders teamed with full-time nurse administrators based within geographic regions. These teams meet monthly with the providers responsible for delivering care in their region and methodically review data on clinical, cost, and service outcomes for each care delivery group. In addition, the leadership teams from across the Intermountain system meet monthly to disseminate successful changes and to discuss learning opportunities and improvement measures [24].

An increase in accuracy, reliability, and strength of data will be necessary to increase trust in the measurement and reporting efforts by both providers and consumers, which will allow for more effective reliance on this information in the future. Given the many challenges, deficiencies, and the extreme complexity involved in efforts to deliver comprehensive, accurate, and reliable information to the public, there are many unique opportunities for orthopaedic surgeons to lead.

A valuable contribution by providers could be made in determining which measures promote performance improvement and which strategies equip providers to translate reporting system scores and results into actions for informing process and improving care. Surgeons could also work with performance improvement foundations such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the Leapfrog group to be directly involved in developing orthopaedic-specific performance measures and risk adjustment tools as well as accurate and cost-efficient instruments for data collection and reporting.

Surgeons could also provide input and comments toward the project on quality measures developed for patients undergoing elective THA and TKA being carried out by organizations such as the Yale-New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (YNHHSC/CORE) [50]. This project, which is a multistakeholder collaboration among orthopaedic surgeons, methodologists, and payers, seeks to use administrative claims data to define valid, risk-adjusted hospital-level outcomes measures that will be used to assess the quality of care for THA and TKA in Medicare patients. Once validated, these measures will be applied for use in public reporting.

Historical accounts including the outcome-driven US Veterans Health Administration (VHA)’s Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) [40], which has evolved into the comprehensive program now known as the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP), and existing initiatives including the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ) [48] indicate public reporting programs are most effective when established in partnership with healthcare providers. The NSQIP began in the mid-1990s under the order of Congress to tackle higher surgical mortality rates in VA hospitals [26]. The project developed a program of data collection, which included risk-adjusted outcome data used for evaluation and also subject to audits and site visits. The NSQIP was successful in reducing mortality rates with similar characteristics at high-performing sites, including standardization, interdisciplinary care, and adherence to guidelines. The WCHQ example displays the operational processes of a physician-led organization that has achieved voluntary public reporting of comparative performance information. The tenets crucial for successful physician engagement included: (1) a focus on quality of patient care as the goal of reporting; (2) performance data that are valid, reliable, trusted by physicians, and attentive to the details of sample size, bias, risk adjustment, and attribution; (3) physician-led development of performance measures (determined to be strongly associated with long-term sustainable quality improvement); (4) sharing of best practices across the statewide consortium of quality improvement-driven healthcare organizations; and (5) the limiting of reporting at the level of the organization (in response to points made by physicians), not the individual clinician, to avoid the isolation of physicians and to acknowledge healthcare delivery is an outcome of the actions of many individuals and the systems that support them.

Although the challenges of quality measurement and reporting are many, orthopaedic surgeons certainly need to be involved in policy formulation and development with a posture that includes both leadership and active learning. As direct implementers of the policies that drive musculoskeletal care, orthopaedic surgeons are best equipped to inform the formulation of evidence-based performance measures and the development of reliable reporting methods in our field. Our leadership and expertise are necessary for facilitating multistakeholder collaborations, which are fundamental for developing effective and reliable performance measures and public reporting mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Epstein (Charlotte Edwards Maguire Medical Library, Florida State University, College of Medicine) for her assistance in formulating the search strategy on PubMed, and Vanessa Chiu, MPH, for assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors (KJB) received financial support from the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This work was performed at the University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Adams JL, Mehrotra A, Thomas JW, McGlynn EA. Physician cost profiling—reliability and risk of misclassification. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1014–1021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0906323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AMA. Principles for Pay for Performance Programs. 2005. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/368/principles4pay62705.pdf. Accessed November 2010.

- 3.AQA. Principles for Public Reports on Health Care. 2006. Available at: http://www.aqaalliance.org/files/ProviderPrinciplesMay06.doc. Accessed November 2010.

- 4.Berwick DM, Wald DL. Hospital leaders’ opinions of the HCFA mortality data. JAMA. 1990;263:247–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440020081037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkmeyer JD, Gust C, Baser O, Dimick JB, Sutherland JM, Skinner JS. Medicare payments for common inpatient procedures: implications for episode-based payment bundling. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1783–1795. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozic KJ, Chiu V. Quality measurement and public reporting in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozic KJ, Chiu VW, Takemoto SK, Greenbaum JN, Smith TM, Jerabek SA, Berry DJ. The validity of using administrative claims data in total joint arthroplasty outcomes research. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozic KJ, Smith AR, Mauerhan DR. Pay-for-performance in orthopedics: implications for clinical practice. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BQI. Enhancing Physician Quality Performance Measurement and Reporting Through Data Aggregation. The Better Quality Information (BQI) to Improve Care for Medicare Beneficiaries Project. Easton, MD: Delmarva Foundation for Medical Care; 2008.

- 10.Christianson JB, Volmar KM, Alexander J, Scanlon DP. A report card on provider report cards: current status of the health care transparency movement. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1235–1241. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CMS. Fiscal Year 2009 Quality Measure Reporting for 2010 Payment Update. December 2010. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/downloads/HospitalRHQDAPU200808.pdf. Accessed May 2010.

- 12.CMS. Hospital Quality Initiatives Overview. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/01_Overview.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed December 20, 2010.

- 13.CMS. 2011 Physician Compare Web Site Background Brief—Section 10331 of PPAC. 2010. Available at: http://www.usqualitymeasures.org/shared/content/Phy%20Com%20Web%20Site_background_paper%20rchell10%2012%202010_LK_ap10%2013in%20508.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2010.

- 14.Colmers. Public Reporting and Transparency, Commission on a High Performance Health System. 2007. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Fund-Reports/2007/Feb/Public-Reporting-and-Transparency.aspx. Accessed November 28, 2010.

- 15.Dranove D, Kessler D, McClellan M, Satterthwaite M. Is more information better? The effects of ‘report cards’ on health care providers. J Polit Econ. 2003;111:555–588. doi: 10.1086/374180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Draper DA, Liebhaber A, Ginsburg PB. High-performance Health Plan Networks: Early Experiences: Center for Health System Change. Issue Brief 111. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferris TG, Torchiana DF. Public Release of Clinical Outcomes Data. Online CABG Report Cards. Available at: www.NEJM.org. Accessed November 28, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Fleming ST, Hicks LL, Bailey RC. Interpreting the Health Care Financing Administration’s mortality statistics. Med Care. 1995;33:186–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haas-Wilson D. Arrow and the information market failure in health care: the changing content and sources of health care information. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2001;26:1031–1044. doi: 10.1215/03616878-26-5-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannan EL, Kilburn H, Jr, Racz M, Shields E, Chassin MR. Improving the outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery in New York State. JAMA. 1994;271:761–766. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510340051033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.HCAHPS Hospital Care Quality from the Consumer Perspective. Available at: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/home.aspx. Accessed December 20, 2010.

- 22.Healthgrades—Guiding Americans to Their Best Health. Available at: http://www.healthgrades.com/. Accessed December 21, 2010.

- 23.IOM. Performance Measurement: Accelerating Improvement. Institute of Medicine Pathways to Quality Health Care Series. Washington, DC: The National Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Medicine; 2005.

- 24.James BC, Savitz LA. How Intermountain trimmed health care costs through robust quality improvement efforts. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 May 19 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Kaiser Permanente. Delivery System Reform. Action Steps and Pay-for-value Approaches. November 4, 2008. Available at: http://xnet.kp.org/newscenter/media/DeliverySystemReform.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2010.

- 26.Khuri SF. Safety, quality, and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Am Surg. 2006;72:994–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lake T, Colby M, Peterson S. Health Plans’ Use of Physician Resource Use and Quality Measures, Final Report. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lansky D, Milstein A. Quality measurement in orthopaedics: the purchasers’ view. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2548–2555. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0999-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leapfrog Group. Informing Choices. Rewarding Excellence. Getting Health Care Right. Available at: www.leapfroggroup.org/cp. Accessed December 29, 2010.

- 30.Mehrotra A, Adams JL, Thomas JW, McGlynn EA. The effect of different attribution rules on individual physician cost profiles. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:649–654. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mihalko WM, Greenwald AS, Lemons J, Kirkpatrick J. Reporting and notification of adverse events in orthopaedics. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:193–198. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milstein A, Lee TH. Comparing physicians on efficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2649–2652. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0706521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.NCQA/HEDIS. National Committee for Quality Assurance: Report Cards. 2010. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/60/Default.aspx. Accessed December 20, 2010.

- 34.Porter M, Teisberg E. Redefining competition in healthcare. Harvard Business Review. 2004:2–14. [PubMed]

- 35.Porter ME. What is value in health care? New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:2477–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.PQRI. Physician Quality Reporting Initiative Measures Codes. 2010. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/PQRI/15_MeasuresCodes.asp. Accessed December 2010.

- 37.PQRI. CMS Physician Quality Reporting Initiative Overview 2010. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/pqri/. Accessed December 20, 2010.

- 38.RAND. Monograph Report Dying to Know: Public Release of information About Quality of Health Care. 2000. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1255/index.html. Accessed November 2010.

- 39.Reid RO, Friedberg MW, Adams JL, McGlynn EA, Mehrotra A. Associations between physician characteristics and quality of care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1442–1449. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubenstein LV, Mittman BS, Yano EM, Mulrow C. From understanding health care provider behavior to improving health care: the QUERI framework for quality improvement. Med Care. 2000;38(Suppl 1):I-129–I-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandy LG, Rattray MC, Thomas JW. Episode-based physician profiling: a guide to the perplexing. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1521–1524. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scholle SH, Roski J, Adams JL, Dunn DL, Kerr EA, Dugan DP, Jensen RE. Benchmarking physician performance: reliability of individual and composite measures. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:833–838. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scholle SH, Roski J, Dunn DL, Adams JL, Dugan DP, Pawlson LG, Kerr EA. Availability of data for measuring physician quality performance. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:67–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sirovich B, Gallagher PM, Wennberg DE, Fisher ES. Discretionary decision making by primary care physicians and the cost of US health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:813–823. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sorbero ME, Damberg CL, Shaw R, Teleki S, Lovejoy S, DeChristofaro A, Dembosky J, Schuster C. Assessment of Pay-for-performance Options for Medicare Physician Services: Final Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; May 2006.

- 46.Wadgaonkar AD, Schneider EC, Bhattacharyya T. Physician tiering by health plans in Massachusetts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2204–2209. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Werner RM, Asch DA. The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information. JAMA. 2005;293:1239–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality. Available at: http://www.wchq.org/about/documents/Embracing_Accountability. Accessed December 20, 2010.

- 49.Wong DA, Herndon JH, Canale ST, Brooks RL, Hunt TR, Epps HR, Fountain SS, Albanese SA, Johanson NA. Medical errors in orthopaedics. Results of an AAOS member survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:547–557. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (YNHHSC/CORE). Measure Instrument Development and Support. August 20, 2010. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/MMS/Downloads/MMSHipKneePublicComments.pdf. Accessed December 29, 2010.