Abstract

Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) is a homohexameric enzyme that catalyzes the reversible oxidative deamination of L-glutamate to 2-oxoglutarate. Only in the animal kingdom is this enzyme heavily allosterically regulated by a wide array of metabolites. The major activators are ADP and leucine, while the most important inhibitors include GTP, palmitoyl CoA, and ATP. Recently, spontaneous mutations in the GTP inhibitory site that lead to the hyperinsulinism/hyperammonemia (HHS) syndrome have shed light as to why mammalian GDH is so tightly regulated. Patients with HHS exhibit hypersecretion of insulin upon consumption of protein and concomitantly extremely high levels of ammonium in the serum. The atomic structures of four new inhibitors complexed with GDH complexes have identified three different allosteric binding sites. Using a transgenic mouse model expressing the human HHS form of GDH, at least three of these compounds were found to block the dysregulated form of GDH in pancreatic tissue. EGCG from green tea prevented the hyper-response to amino acids in whole animals and improved basal serum glucose levels. The atomic structure of the ECG-GDH complex and mutagenesis studies is directing structure-based drug design using these polyphenols as a base scaffold. In addition, all of these allosteric inhibitors are elucidating the atomic mechanisms of allostery in this complex enzyme.

Keywords: glutamate dehydrogenase, insulin regulation, polyphenols, allostery, subunit communication, protein dynamics

Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) is found in all organisms and catalyzes the reversible oxidative deamination of L-glutamate to 2-oxoglutarate using NAD+ and/or NADP+ as coenzyme [1]. In nearly all organisms, GDH is a homohexameric enzyme composed of subunits comprised of ~500 residues in animals and ~450 residues in the other kingdoms. While the chemical details of the enzymatic reaction have been tightly conserved through the epochs, the metabolic role of the enzyme is not. Most striking is the fact that GDH from animal sources is allosterically regulated by a wide array of metabolites while it is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level in the other kingdoms.

In animals, the two major opposing allosteric regulators, ADP and GTP, appear to exert their effects via abortive complexes [2–4]. Abortive complexes are where the product is replaced by substrate before the reacted coenzyme has a chance to dissociate; GDH•glutamate•NAD(P)H in the oxidative deamination reaction and GDH•2-oxoglutarate•NAD(P)+ in the reductive amination reaction. Once these complexes form, coenzyme binds very tightly and slows down enzymatic turnover by inhibiting product release. ADP is an activator believed to act, at least in part, by destabilizing the abortive complex [2, 3]. In contrast, GTP is a potent inhibitor and is thought to act by stabilizing abortive complexes [5]. GTP binding is antagonized by phosphate [6] and ADP [7], but is proposed to be synergistic with NADH bound in the non-catalytic site [6]. Finally, ADP and GTP bind in an antagonistic manner [7] either due to steric competition or due to competing effects on abortive complex formation. As discussed below, it is likely that these regulators act by modulating the enzyme dynamics [8, 9].

Mammalian GDH is also regulated by several other types of metabolites. Leucine, as well as some other monocarboxylic acids, has been shown to activate mammalian GDH [10] by increasing the rate-limiting step of coenzyme release in a manner similar to ADP [11]. Since leucine is a weak substrate for GDH, clearly one binding site is the active site, but it is unclear whether there is a second, allosteric site. Palmitoyl-CoA [12] and diethylstilbestrol [13] are inhibitors of mammalian GDH, but nothing is known about their binding location.

The structure of animal GDH

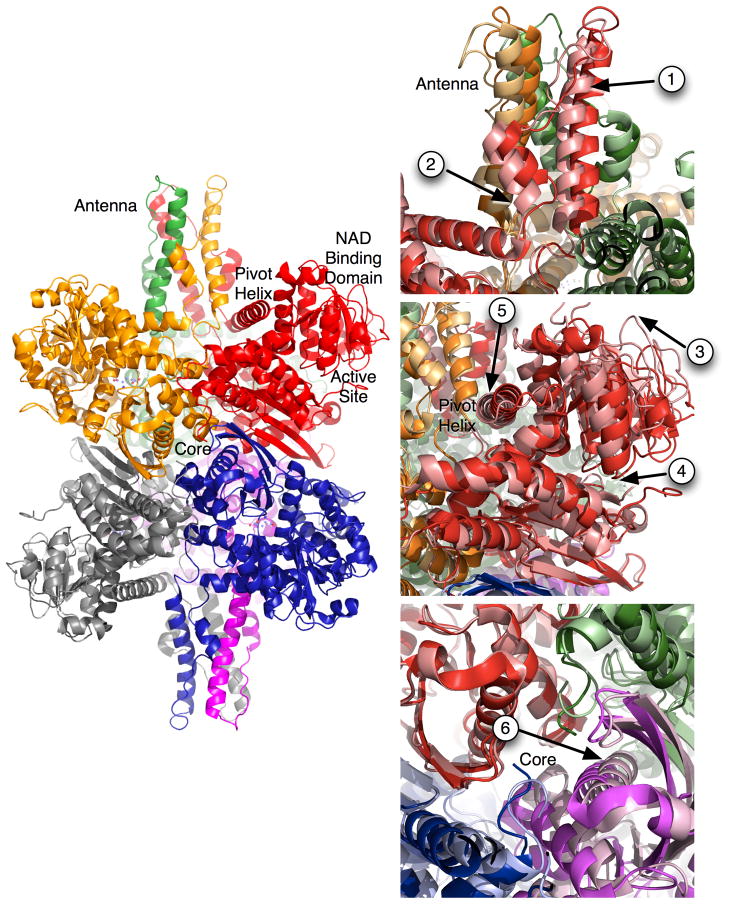

The crystal structures of the bacterial [14–16] and mammalian forms [8, 17] of GDH have shown that the general architecture and the locations of the catalytically important residues have remained unchanged throughout evolution. The structure of GDH (Figure 1) is essentially two trimers of subunits stacked directly on top of each other with each subunit being composed of at least three domains [8, 9, 17, 18]. The bottom domain makes extensive contacts with a subunit from the other trimer. Resting on top of this domain is the ‘NAD binding domain’ that has the conserved nucleotide-binding motif. Animal GDH has a long protrusion, ‘antenna’, rising above the NAD binding domain that is not found in bacteria, plants, fungi, and the vast majority of protists. The antenna from each subunit lies immediately behind the adjacent, counter-clockwise neighbor within the trimer. Since these intertwined antennae are only found in the forms of GDH that are allosterically regulated by numerous ligands, it is reasonable to speculate that it plays an important role in regulation.

Figure 1.

Structure of animal GDH. On the left is the structure of GDH with each subunit represented by a ribbon diagram with each subunit represented by different colors. On the right side are magnified views of the regions of GDH that exhibit large conformational changes as the catalytic cleft opens and closes. The darker hues correlate with the structure of GDH in the closed conformation and the lighter hues represent the open conformation. The arrows highlight the key movement points as described in the text.

The first crystal structure of bovine GDH (bGDH) included glutamate, NADH, and GTP [19]. Initial crystals of the apo form of GDH had been previously obtained, but had an extremely large unit cell and diffracted to modest resolution. NADH and glutamate form a tightly bound abortive complex in the active site. NADH binds to a second site and acts synergistically with the inhibitor GTP [6] to further increase the affinity of glutamate and NADH to the active site [5, 6, 20]. Therefore, together, it was reasoned that high concentrations of these ligands would be sufficient to overcome the negative cooperativity exhibited by GDH with respect to coenzyme binding [21–24] so that homogenous and saturated GDH could be crystallized.

GDH dynamics

From the structures of bGDH with and without active site ligands, it is possible to observe the closure of the active site cleft, along with some of the large conformational changes that occur throughout the hexamer during each catalytic cycle [8, 9, 17, 18]. Details of these conformational changes are summarized in Figure 1. In this figure, the closed conformation (substrate bound) is represented by darker hues. When substrate is release from the deep recesses of the active site cleft (arrow 4), the entire enzyme undergoes a number of large conformational changes. Upon release, the coenzyme binding domain rotates up by ~18° (arrow 3). The antenna domain in each subunit lies behind the NAD binding domain counter clockwise subunit within each trimer. As the catalytic cleft opens, the base of each of the long ascending helices in the antenna appears to rotate out in a clockwise manner as the pivot helix of the adjacent subunit is pushed back (arrow 5). This motion is translated up through the antenna and gives it a clockwise washing machine motion (arrow 1). As the catalytic mouth opens, the short distended helix in the descending loop of the antenna coils back into a longer, better ordered helix akin to releasing an extended spring (arrow 2). Finally, the core of the entire hexamer seems to expand as the mouth opens (arrow 6). The three pairs of subunits that sit on top of each other move as a rigid units away from each other, opening the cavity at the core of the hexamer. As is further detailed in subsequent sections, it is apparent that animal GDH is controlled allosterically via ligand interactions at a number of these flex points.

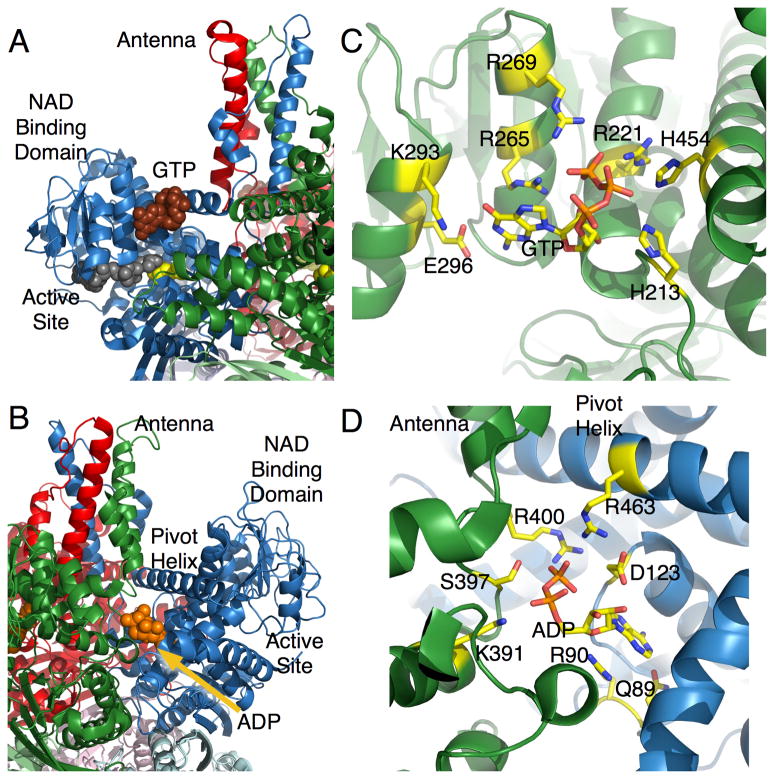

The GTP inhibition site

GTP is a potent allosteric inhibitor for the reaction and binds at the base of the antenna, wedged in between the NAD binding domain and the pivot helix [17, 18] (Figure 2A,C). It is important to note that this binding site is only available for GTP binding when the catalytic cleft is closed. Therefore, it is likely that after GTP binds to the ‘closed’ conformation, making it more difficult for the ‘mouth’ to open and release product. This is entirely consistent with the finding that GTP inhibits the reaction by slowing down product release and concomitantly increasing the binding affinity of substrate and coenzyme [5, 6, 20]. The vast majority of the interactions between GTP and bGDH involve the triphosphate moiety with the majority of the salt bridges being made with the γ-phosphate (Figure 2C). This explains why, in terms of inhibition, GTP≫GDP>GMP [2]. This site is essentially an energy sensor where if the mitochondrial energy level is high, then the GTP (and ATP) levels will be elevated and GDH will be inhibited.

Figure 2.

Locations of the activator, ADP, and inhibitor, GTP, regulatory sites. A) the structure of GTP bound to the closed conformation of GDH. GTP is represented by the brown spheres, coenzyme in grey, and glutamate in yellow. B) ADP (orange) binds behind the catalytic cleft, under the pivot helix. C) Magnification of GTP bound to GDH. D) Magnification of ADP bound to GDH.

The ADP/second NADH site paradox

Perhaps one of the most confusing regulatory sites on mammalian GDH is the allosteric activator, ADP, binding site (Figure 2). The existence of a second NADH binding site per subunit was demonstrated both kinetically and by binding analysis [25–27]. It was observed that NADH alone binds with a stoichiometry of 7–8 molecules per hexamer. In the presence of glutamate, NADH binds more tightly and the stoichiometry increases to 12 per hexamer [27]. Similarly, GTP also increases the affinity and binding stoichiometry [6]. This second coenzyme site strongly favors NADH over NADPH with Kd’s of 57μM and 700μM, respectively. In the case of oxidized coenzyme, NAD+, two binding sites were also observed. While the recent structures of the various complexes have demonstrated that ADP and NAD(H) bind to the same site [9, 18], this was first suggested by ADP binding competition with NAD+ [28] and NADH [7]. Further, these binding studies provided direct evidence that GTP and glutamate enhance binding of NADH to a second site and ADP blocks binding of both NAD+ and NADH to a second site. Since, in general terms, NADPH is involved in anabolic reactions in the cell while NADH is important for catabolic processes, it is possible that this regulation offers a feedback mechanism to curtail glutamate oxidation when catabolic reductive potentials (NADH) are high.

In nearly every way, ADP acts in a manner opposite to NADH binding to this site. In the oxidative deamination reaction, ADP activates at high pH, but inhibits at low pH with either NAD+ or NADP+ as coenzyme. In the reductive amination reaction, ADP is a potent activator at low pH and low substrate concentration. At pH 6.0, high concentrations of α-KG and NADH, but not NADPH, inhibit the reaction. This substrate inhibition is alleviated by ADP [4]. Therefore, while GTP and glutamate bind synergistically with NADH to inhibit GDH, ADP activates the reaction by decreasing the affinity of the enzyme for coenzyme at the active site. Under conditions where substrate inhibition occurs, this activates the enzyme. However under conditions where the enzyme is not saturated (e.g. low substrate concentrations), this loss in binding affinity causes inhibition. Put another way, under conditions where product release is the rate-limiting step, ADP greatly facilitates the catalytic turnover. It should be noted that the fact that substrate (2-oxoglutarate) inhibition in the reductive amination reaction is only observed using NADH as coenzyme was suggested to be due to NADH (but not NADPH) binding to the second coenzyme site. Further, it was suggested that ADP activation under these conditions was due to ADP displacement of NADH from the second allosteric site [2].

ADP binds behind the NAD binding domain and immediately under the pivot helix [9]. As shown in Figure 2D, R459 lies on the pivot helix and interacts with the phosphates of the bound ADP. It was proposed that this interaction might facilitate the rotation of the NAD binding domain and the release of product [9]. To test this, R459 (R463 in human GDH) was mutated to an alanine and this led to a loss in ADP activation. This essentially suggests that ADP activates the reaction by ‘pulling’ on the back of the NAD binding domain to help open the active site cleft and facilitating product release. More precisely, ADP likely decreases the energy required to open the catalytic cleft.

To better understand how ADP can activate GDH and to put allosteric regulation in broader context, it is helpful to review the two main models for explaining homotrophic allosteric regulation; the concerted and sequential models. The concerted, or symmetrical, model was first proposed by Monod, Wyman, and Changeux [29]. In this model (MWC), all subunits in an oligomer have the same structure but that they can exist in two different states; relaxed (R) and tense (T) where the relaxed state binds ligand tighter than the tense state. In enzymes exhibiting positive cooperativity, the structural equilibrium of the whole oligomer shifts towards the R state and the affinity of the substrate to the enzyme increases as the substrate binds to the active site. While this model is easily applied to systems exhibiting positive cooperativity, it fails to describe negative cooperativity. The concerted model would require substrate to preferentially bind to the low affinity species (T state) in order to decrease affinity with increasing saturation.

To explain how negative cooperativity might occur, Koshland, Nemethy, and Filmer developed the sequential model that is applicable to both negatively and positively cooperative enzymes [30, 31]. The main difference between the two models is that the sequential model does not require all of the subunits in the oligomer to adopt the same conformation. Instead, substrate binding to a subunit can induce a particular conformation and this change can affect other subunits in the oligomer by making it either thermodynamically harder or easier for them to make the same transition. These transitions become easier as the enzyme becomes saturated in the case of positive cooperativity and are harder with negative cooperativity. In the case of GDH, that exhibits negative cooperativity with respect to coenzyme binding, substrate binding to the first subunit may cause the catalytic cleft to close and, because of interactions at the subunit interfaces, this conformation transition makes it harder (negative cooperativity) for the adjacent subunits to clamp down upon substrates as they bind. Therefore, the sequential model is attractive since it can be applied to both positively and negatively cooperative systems but also allows for more independent and fluid structures among the subunits in the oligomer. From the structures of GDH, we are not seeing obvious ‘R’ and ‘T’ states of the enzyme and the MWC model seems overly simplistic even for heterotrophic allosteric regulation. Indeed, the subunits all have slightly different conformations in the apo form of GDH. Instead, it seems more likely that all of the conformational changes that occur at subunit interfaces, that are required for for catalytic turnover, are likely facilitated by activating ligands such as ADP while inhibited by inhibitors such as GTP.

The structures of GDH complexed with NADH, NADPH, and NAD have all been determined [18]. Because NADH (but not NADPH) has been suggested to be an inhibitor of the reaction, it is somewhat surprising that it binds to the ADP activation site [9]. The adenosine-ribose moiety location exactly matched that of ADP. The electron density of the ribose-nicotinamide moiety was much weaker and was initially built in two alternative conformations. However, the stronger density for this portion of NADH suggests that it points down into the interface between adjacent subunits. As predicted from the binding studies reviewed above, NADPH was found bound to the active site but not the second, allosteric site.

NAD+ was found to bind in a manner essentially identical to NADH [18]. From steady state kinetic analysis, it was initially thought that NAD+ binding to this second site causes activation of the enzyme [25], even though NADH causes apparent inhibition. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that this apparent activation was due to negatively cooperative binding with respect to coenzyme [32]. Therefore, it is not clear what difference there might be, if any, between NAD+ and NADH binding to GDH at this location. It is interesting to note that modification of the ADP site with an ADP analog did not eliminate NADH inhibition [33]. Perhaps this is due to the nicotinamide moiety still binding to the pocket between the subunits in spite of AMPSBDB being bound to R459. As will be detailed below, recent studies on new GDH inhibitors have shown that compounds binding to subunit interfaces, and at the ADP site itself, can be potent inhibitors of the enzyme. Perhaps the ribose-nicotinamide moiety is acting in a similar manner.

The physiological role of ADP activation is easily understood; when the energy level of the mitochondria is low and ADP levels are high, the catabolism of glutamate is facilitated for energy production. However, the possible in-vivo role of NADH inhibition is less clear. Since NADH inhibition is observed at concentrations above 0.2mM (e.g. see [34]), but only reaches ~50% inhibition at 1mM NADH, NADH inhibition seems more likely to work synergistically with GTP regulation; under conditions of high reductive potential, NADH acts with GTP to keep GDH in a tonic state.

At an atomic level, there is a very clear delineation between ligands binding to the open and closed conformations. NADH alone only binds to the active site. When glutamate is added, the catalytic cleft closes and NADH is able to bind to the second, allosteric site. Further, the GTP binding site collapses when the catalytic cleft opens and therefore GTP also favors the closed conformation. Therefore, the synergism between NADH and GTP is likely due to both ligands binding to, and stabilizing the closed conformation. Again, this supports the contention that NADH inhibition alone may not have a significant physiological role, but rather its main function is the enhancement of GTP inhibition.

Role of allosteric regulation in insulin homeostasis

The difference between the allosteric regulation of GDH from animals and the other kingdoms has been known for decades, but possible roles for allosteric regulation in mammalian GDH is only starting to emerge. Of growing interest is the fact that loss of inhibition of GDH causes inappropriate insulin secretion. There have been three GDH-mediated forms of hyperinsulinism identified thus far: hyperinsulinism/hyperammonemia (HHS) due to mutations that abrogate GTP inhibition, mutations in NAD-dependent deacetylase (SIRT4), and knock out mutations of short-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCHAD).

HHS

HHS was one of the first diseases that clearly linked GDH regulation to insulin and ammonia homeostasis [35]. In brief, the mitochondrion of the pancreatic β-cells plays an integrative role in the fuel stimulation of insulin secretion. The current concept is that mitochondrial oxidation of substrates increases the cellular phosphate potential that is manifested by a rise in the ATP4−/MgADP2− ratio. The elevated ATP concentration closes the plasma membrane KATP channels, resulting in the depolarization of the membrane potential. This voltage change across the membrane opens voltage gated Ca2+ channels. The rise of free cytoplasmic Ca2+ then leads to insulin granule exocytosis.

The connection between GDH and insulin regulation was initially established using a nonmetabolizable analog of leucine [36, 37], BCH (β-2-aminobicycle(2.2.1)-heptane-2-carboxylic acid). These studies demonstrated that activation of GDH was tightly correlated with increased glutaminolysis and release of insulin. In addition, it has also been noted that factors that regulate GDH also affect insulin secretion [38]. Subsequently, it was postulated that glutamine could also play a secondary messenger role and that GDH plays a role in its regulation [39–41]. The in-vivo importance of GDH in glucose homeostasis was demonstrated by the discovery that a genetic hypoglycemic disorder, the HHS syndrome, is caused by loss of GTP regulation of GDH [35, 42, 43]. Children with HHS have increased β-cell responsiveness to leucine and susceptibility to hypoglycemia following high protein meals [44]. This is likely due to uncontrolled catabolism of amino acids yielding high ATP levels that stimulate insulin secretion as well as high serum ammonium levels. The elevation of serum ammonia levels reflects the consequence of altered regulation of GDH leading to increased ammonia production from glutamate oxidation, and possibly also impaired urea synthesis by carbamoylphosphate synthetase (CPS) due to reduced formation of its activator, N-acetyl-glutamate, from glutamate. Essentially, this genetic lesion disrupts the regulatory linkage between glucose oxidation and amino acid catabolism. During glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in normal individuals, it has been proposed that the generation of high energy phosphates inhibits GDH and promotes conversion of glutamate to glutamine, which, alone or combined, might amplify the release of insulin [39, 40].

While the glucose and ammonium levels in patients with HHS are alone sufficient to potentially cause damage to the CNS, recent studies have suggested a high correlation between HHS and childhood-onset epilepsy, learning disabilities, and seizures [45]. Some of these pathologies have been shown to be unrelated to serum glucose and ammonium levels. This is not entirely surprising considering the importance of glutamate and its derivative, γ-aminobutyric acid, as neurotransmitters. The current treatment for HHS is to pharmaceutically control insulin secretion (e.g. diazoxide, a potassium channel activator) but this does not address the serum ammonium and CNS pathologies.

SIRT4 mutations

Sirt2 or sirtuins (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog) are found in all organisms and most are NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. The sirtuins have been shown to be implicated in aging and regulate transcription, involved in stress response, and apoptosis. Recent studies have shown that SIRT4, a mitochondrial enzyme, uses NAD to ADP-ribosylate GDH and inhibit its activity [46, 47]. When SIRT4 knockout mice were generated, the loss of SIRT4 activity led to the activation of GDH and, much like HHS due to the loss of GTP inhibition, upregulated amino acid-stimulated insulin secretion [47]. In addition, they found that, with regard to that ADP-ribosylation, GDH activity in SIRT4 −/− mice was similar to mice on a calorie restriction diet regime. This suggests that normally SIRT4 in the β cell mitochondria represses GDH activity by ADP-ribosylation and this regulation is removed during times of low caloric intake.

SCHAD mutations

A form of recessively inherited hyperinsulinism has been recently identified to be associated with a deficiency of a mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation enzyme, the short-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCHAD) encoded by the HADH gene on 4q [48–50]. Children with this defect have recurrent episodes of protein-induced hypoglycemia [51] that can be controlled with the KATP channel agonist diazoxide. These patients also have serum accumulation of fatty acid metabolites such as 3-hydroxybutyryl-carnitine and urinary 3-hydroxyglutaric acid [48, 50]. Similar to HHS, these patients are also have severe dietary protein sensitivity [48]. However, the loss of SCHAD activity is at odds with increased insulin secretion observed in HHS since it is expected to decrease ATP production. In addition, other genetic disorders of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation do not lead to hyperinsulinism [52].

Recent studies have now explained this seeming paradox by suggesting that SCHAD regulates GDH activity via protein-protein interactions [53]. From immunoprecipitation and pull-down analysis, it is apparent that GDH and SCHAD interact as had been previously suggested [54]. This interaction inhibits GDH activity by decreasing GDH affinity for substrate. This effect was found to be limited to the pancreas presumably because of the relatively high levels of SCHAD found in this tissue. This would also explain why SCHAD deficient patients do not have a concomitant increase in serum ammonium levels as observed in HHS. These results are particularly interesting since it strongly suggests that part of GDH regulation comes from associating as a large multienzyme complex in the mitochondria. This also suggests a linkage between fatty acid and amino acid oxidation and fits in will with the evolution of allostery as discussed in the next section.

Evolution of GDH allostery

It has been known for some time that animal GDH contains an internal 48-residue insert compared to GDH from the other kingdoms. From the structure of animal GDH, we now know this insert forms the antenna region (Figure 1). What was not at all clear was when and why the antenna evolved and whether it was linked to the complex pattern of allostery in animal GDH. The only organisms other than animals that have this 48-residue insert are the Ciliates. This possible evolutionary ‘missing link’ was then further analyzed via kinetic and mutagenesis analyses using Tetrahymena GDH (tGDH) [55]. Like mammalian GDH, tGDH is activated by ADP and inhibited by palmatoyl CoA. However, like bacterial GDH, tGDH is coenzyme specific (NAD(H)) and is not regulated by GTP or leucine. Therefore, with regard to allosteric regulation, tGDH is indeed an evolutionary ‘missing link’ between bacterial and animal GDH.

From structural studies, it was clear that the antenna was not involved in ADP or GTP binding [9, 17, 18]. However, when the antenna on human GDH was genetically replaced by the short loop found in bacterial GDH, the enzyme lost GTP, ADP, and Palmitoyl-CoA regulation [55]. When the Ciliate antenna was spliced onto human GDH, this hybrid enzyme had a fully functional repertoire of mammalian allostery. This demonstrated that the antenna is essential for allosteric regulation by GTP and ADP while not being directly involved in their binding. Evolutionarily, this also demonstrated that the antenna in Ciliate GDH is capable of transmitting the GTP inhibitory signal, but GTP regulation was apparently not needed in the Ciliates.

This suggests that GDH allostery evolved in at least a two-step process. The first evolutionary step may have been due to the changing functions of the cellular organelles as the Ciliates branched off from the other kingdoms. In the other eukaryotic organisms, all fatty acid oxidation occurs in the peroxisomes [56, 57]. In the Ciliates, fatty acid oxidation is shared between the peroxisomes and the mitochondria [58, 59]. Eventually, all medium and long chain fatty oxidation moved into the mitochondria in animals [60, 61]. This pattern of regulation suggests that the catabolism of amino acids is down regulated when there are sufficient levels of fatty acids. Only when the mitochondria have run low of fatty acids and its energy state is low (i.e. high ADP levels) will amino acids be catabolized. Therefore, allostery evolved to coordinate the growing complexity of mitochondrial metabolism and the antenna feature is needed to exact this regulation.

The second step of evolution was to add leucine and GTP allostery as animals needed even more sophisticated and rapid-response regulation of GDH activity. In animals, GDH is found in high levels in the central nervous system (CNS), pancreas, liver, and kidneys. In each organ, the levels of glutamate need to be controlled by very different physiological signals. These disparate roles for GDH are more than likely why GDH in animals has such sophisticated allosteric regulation compared to all other organisms.

In the pancreas, GDH needs to be activated when amino acids (protein) are ingested to promote insulin secretion and appropriate anabolic effects on peripheral tissues. In the glucose-fed state, triphosphate levels are high and GDH needs to be inhibited to redirect amino acids into glutamine synthesis in order to amplify insulin release. In the liver, GDH needs to be suppressed when other fuels, such as fatty acids, are available, but increased when surplus amino acids need to be oxidized. To this end, mammals added layers of regulation onto Ciliate GDH to include leucine activation and GTP inhibition. The choice of leucine as a regulator is likely not an accident, because leucine is an essential amino acid not made by humans and also one of the most abundant amino acid in protein and therefore provides a good measure of protein consumption. Similarly, the marked sensitivity of GDH for GTP over ATP is also not likely accidental. Most of the ATP in the mitochondria is produced from oxidative phosphorylation that is driven by the potential across the mitochondrial membrane created by NADH oxidation. Therefore, the number of ATP molecules generated from one turn of the TCA cycle can vary between 1 and 29. In contrast, one GTP is generated per turn of the TCA cycle and there is a slow mitochondria/cytoplasm exchange rate. Therefore, the GTP/GDP ratio is much better metric of TCA cycle activity than the ATP/ADP ratio. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that mitochondrial GTP, but not ATP, regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [62]. This is also consistent with the HHS disorder in that, without GTP inhibition of GDH, glutamate will be catabolized in an uncontrolled manner, the TCA cycle will generate more GTP, and more insulin will be released. Therefore, the addition of GTP and leucine regulation to GDH makes it acutely sensitive to glucose and amino acid catabolism with obvious implications for insulin homeostasis. It is also likely that this complex network of allostery was needed to accommodate the differing regulation needed by the CNS and ureagenesis.

High throughput screening for new allosteric inhibitors

While the hypersecretion of insulin can be controlled with compounds such as diazoxide [63], this does not address the serum ammonium and CNS pathologies. To this end, high throughput screening was used to find new inhibitors of GDH to control the dysregulated GDH in HHS [64]. Since GDH utilizes commonly found substrate, glutamate, and coenzymes, NAD(P)+, it was essential to design the high throughput screen to avoid selection of substrate and coenzyme analogs. To that end, very high concentrations of both coenzyme and substrate were used during the screening. This proved to be efficacious in that none of the compounds exhibited signs of competitive inhibition.

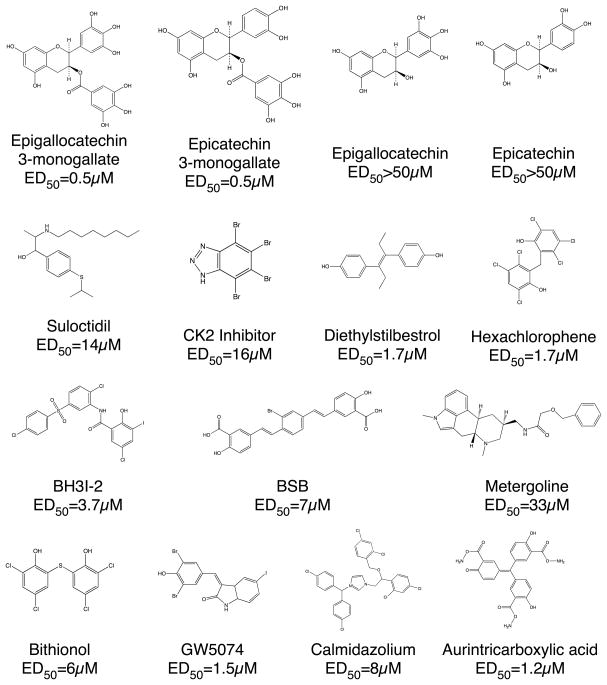

Of the most active compounds (Figure 3), a number of them have similar known pharmaceutical activities. The first group of active compounds (ATA and CK2-inhibitor) likely inhibits GDH by interacting with one of the several purine-binding sites (ADP, GTP, or coenzyme binding sites). Aurintricarboxylic acid (ATA) is an inhibitor of nucleases [65] and topoisomerases [66] and has been shown to inhibit protein-nucleic acid interactions [67]. CK2-inhibitor is a cell-permeable and highly selective ATP/GTP competitive inhibitor of casein kinase-2 [68].

Figure 3.

Some of the new allosteric inhibitors identified by high throughput screening.

A second group of active compounds (BSB and BH3I-2) act on their targets by binding to protein-protein interfaces. BSB is able to permeate living cells, cross the blood-brain barrier, and bind to intracellular amyloid peptides associated with Alzheimer’s disease [69]. In addition, BSB was shown to inhibit a cellular model for transmissible spongiform encephalophathy with an ED50 of ~1.4μM [70]. BH3I-2 inhibits the interaction between the BH3 domain and Bcl-xL [71] with a Ki of ~4–6μM. It is tempting to speculate that these compounds might interfere with the large domain motions associated with catalytic turnover.

Interestingly, a number of these GDH inhibitors also have activity on systems related to calcium binding and uptake. Suloctidil is a calcium channel blocker [72] that also can inhibit caspase-3 [73]. Calmidazolium is a calmodulin antagonist that has a number of activities including the inhibition of calcium channels [74], and calcium-dependent kinases [75].

The remaining compounds have a wide range of pharmaceutical activities but all are polyaromatics. Metergoline is a non-selective serotonin receptor antagonist, known to have an effect on 5HT1A, 5HT1D and 5HT2C receptors [76, 77]. Diethylstilbestrol is a synthetic non-steroidal substance with estrogenic properties [78] and used in the treatment of prostatic cancer. Hexachlorophene and the very similar bithionol both have general bactericidal and fungicidal activity but their exact mechanism of action is unknown. Bithionol and hexachlorophene are small hydrophobic compounds that are similar to the previously identified inhibitor diethylstilbestrol [13]. Common to the larger compounds, these have least two aromatic rings. Finally, the catechins are polyphenolic compounds that are relatively unstable in solution due to their antioxidant activity. However, since ECGC and ECG, but not EC and EGC, inhibit GDH, catechin inhibition is unrelated to the antioxidant activity.

Structures of Drug/GDH complexes

From the highly disparate chemical properties of the lead compounds, it seemed more than likely that the various classes were binding to different allosteric sites on GDH. The atomic structure of the various GDH-drug complexes not only offers a means to elucidate how these new allosteric sites can inhibit GDH activity, but are also invaluable for further drug design.

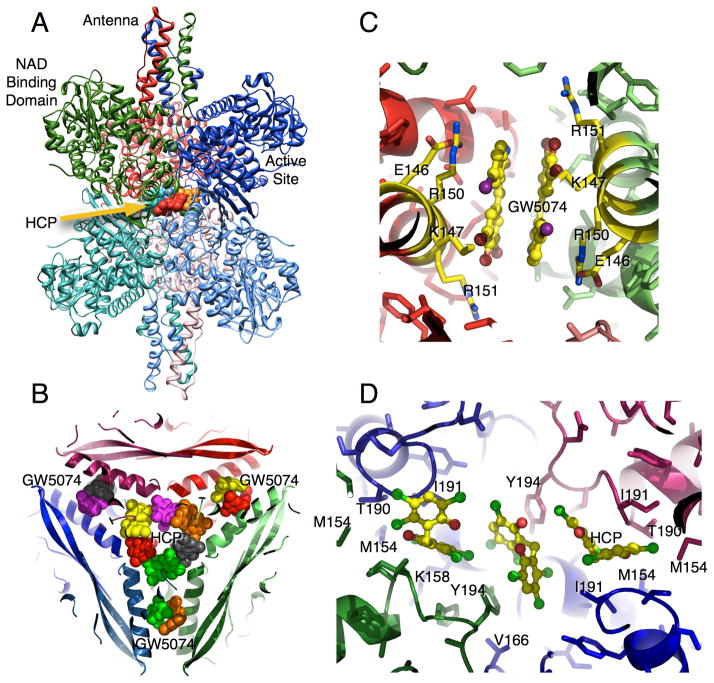

The structure of hexachlorophene (HCP) bound to GDH

In the GDH-HCP complex, six molecules of HCP form a ring in the inner cavity of the hexamer (Figure 4B,D). The majority of the interactions between HCP and GDH are hydrophobic, but there is also an almost ‘chain link’ of aromatic stacking interactions. HCP binds in two orientations. In the first, the rings of HCP approximately stack against two Y190 sidechains from diagonally adjacent subunits. HCP in the other binding orientation makes hydrophobic interactions with M150, I187, Y190 and the methylene side chain atoms from T186 and K154. In addition, the aromatic rings of the HCP molecules stack against each other in this ring conformation. It should be noted that there is apparent positive cooperativity in HCP effects with increasing drug concentrations [64]. Perhaps the positive cooperativity is due to the formation of this ‘chain link’ ring either by increasing the affinity of the drug or by increasing its inhibitory effect.

Figure 4.

Binding sites for GW5074/bithionol and HCP. A) Ribbon diagram of GDH complexed with HCP. HCP binds as a ring inside the innermost core of the hexamer. B) GW5074 and bithionol bind to the same location halfway between the core and the exterior of GDH as apposed to HCP that binds to the innermost core.

Biothionol and GW5074 complex structures

Bithionol and GW5074 do not bind to the same site as HCP (Figure 4B,C). While HCP binds to the inner core, these two drugs bind halfway between the core and the exterior of the hexamer. This is in contrast to the binding geometry of HCP where the internal cavity is blocked off from the exterior solvent mainly by the antenna structure. Two drug molecules form pairs that are related by the two-fold axes in the hexamer. The binding environments of the two drugs are essentially identical. Residues 138–155 of the glutamate-binding domain form an α-helix that makes most of the contact between diagonal subunits and draw closer together when the catalytic cleft is closed (Figure 1). These two drugs stack against each other and interact with hydrophobic residues and the aliphatic portions of the polar and charged side chains of residues K143, R146, R147, and M150 (Figure 4C). These drugs, therefore, appear to directly bind to the area that compresses during mouth closure.

Some very recent structural results on GDH from an extremely thermophilic bacteria, Thermus thermophilus, suggest that this bithionol/GW5074 binding site might be involved in leucine allosteric activation [79]. There are two forms of GDH in T. thermophilus, GdhA and GdhB, that can form various combinations of GdhA/GdhB heterohexamers. GdhA is catalytically inactive and may serve a regulatory function while GdhB catalyzes the reaction. Unlike GDH from non-animal sources, T. thermophilus GDH is activated by leucine. This is particularly unusual since even GDH from Tetrahymena, that has an antenna, is not regulated by leucine [55]. From the structures of GdhB complexed with glutamate and GdhA2/GdhB4 complexed with leucine, Tomita, et al., found that these amino acids also bind at the subunit interface immediately adjacent to the bithionol/GW5074 site. The location of this possible allosteric leucine activation site was supported by mutations of the contact residues that abrogated leucine activation. The connection between this site and leucine activation in animal GDH needs to be confirmed, but it is not at all clear why T. thermophilus would need leucine regulation while other bacteria does not.

Structure of ECG bound to GDH

EGCG/ECG is quite different than the previous three compounds (Figure 5). These polyphenols are extremely hydrophilic and ECG interactions with GDH are dominated by polar interactions and bind to ADP site [80]. While the other inhibitors were able to bind to GDH in the closed conformation, ECG appears to have pushed the structural equilibrium towards the open conformation in spite of the presence of high concentrations of Glu and NADPH. Indeed, ECG was never observed bound to GDH in the closed conformation even when the crystals were soaked in very high concentrations of ECG. This is the same as what was observed when crystallizing the ADP/GDH complex [9].

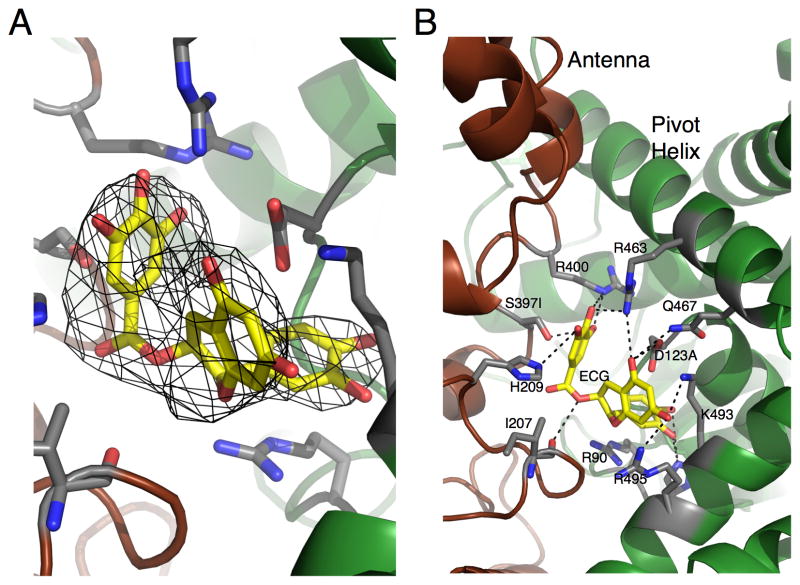

Figure 5.

Location of the ECG/EGCG binding site. A) Six-fold averaged electron density of the bound ECG molecule. B) Structure of ECG bound to GDH with the contact residues highlighted.

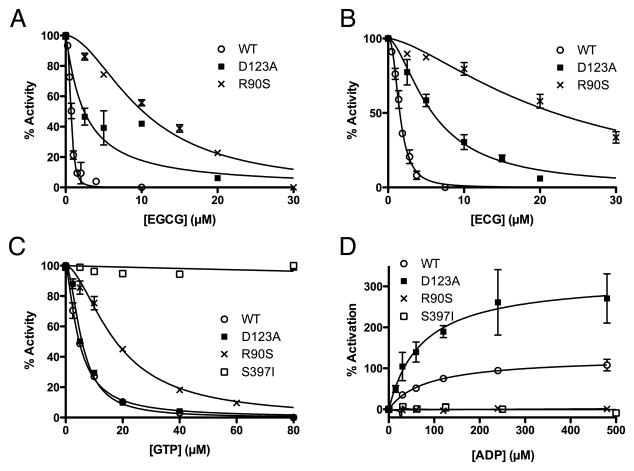

Our previous studies demonstrated that a single mutation (R463A) on the pivot helix abrogated ADP activation without affecting ADP binding (as per TNP-ADP binding). From this we suggested that ADP might be facilitating enzymatic turnover by decreasing the energy require to open the catalytic cleft [9]. Mutagenesis studies on the ECG/EGCG binding site suggest it may be more complicated than that (Figure 6). The guanidinium group of R90 stacks up against the aromatic rings in both ECG and ADP. This interaction is likely essential for both regulators since the R90S mutation essentially eliminated polyphenol inhibition as well as ADP activation. This mutation, however, does have some effect on GTP inhibition even though R90 is quite distal to the GTP site. This may be due to the fact that R90 hydrogen bonds to a loop in the adjacent subunit that lies immediately beneath the GTP binding site. D123 lies beneath the pivot helix and hydrogen bonds with the ribose ring on ADP and with a phenolic group on ECG. From this location, it is not surprising that the D123A mutation had no effect on GTP inhibition but did affect polyphenol inhibition. What is surprising, however, is that this mutation actually accentuated ADP activation without significantly affecting its Kact. This may be due to the interactions between D123 and R463. These two side chains form a salt bridge and D123 may shield some of the charge on R463. By removing D123, the R463 interaction with the β-phosphate on ADP may be strengthened, thereby and improving the ability of ADP to open the catalytic cleft. This is essentially the opposite as the R463A mutation that eliminates ADP activation by eliminating the charge interaction between R463 and ADP [9]. S397 lies at the base of the antenna and the S397I mutation greatly destabilizes the enzyme while abrogating both GTP and ADP regulation. This may simply be due to the marked sensitivity of the antenna region as exemplified by the fact that removing the antenna also eliminates GTP and ADP activation [55].

Figure 6.

The effects of mutations in the ECG/EGCG binding on EGCG inhibition (A), ECG inhibition (B), GTP inhibition (C), and ADP activation (D).

The fact that EGCG/ECG inhibits GDH activity by binding to the ADP site poses a number of questions with regard to the mechanism of ADP activation. Under conditions where product release is not the rate-limiting step (e.g. low substrate or coenzyme concentrations), ADP inhibits the reaction. In contrast, ECG/EGCG inhibits under all conditions [81]. There are at least two possible reasons for this difference. The first model is that ECG/EGCG affects the overall Gibbs free energy of the protein. The fact that ECG/EGCG has a much tighter binding (as per the much lower ED50) may suggest that these compounds decrease the Gibbs free energy of the protein and in turn may make conformational changes more difficult. In this case, the lower energy conformation is that of the ‘open’ state. This implies that there may not be a particular interaction with ECG/EGCG responsible for inhibition, but rather a series of interactions that increase affinity and decrease the energy state of the protein. Alternatively, it may be that interactions like that found with D123 specifically interfere with the more subtle conformational changes that occur in this area as the catalytic cleft opens and closes. This latter model suggests that improving binding affinity of an ADP analog without these specific interactions would not improve the activation efficacy. From work with drugs to the common cold virus that block uncoating by increasing entropy [82–84], it seems more likely that ECG/EGCG inhibits GDH mainly by changing the overall energy state of the enzyme rather than specific interactions.

The fact that the inhibitor, ECG/EGCG, and activator, ADP, both bind to the same site makes for an interesting starting point for structure based drug design. Analogs of ADP can be made that create interactions with D123 like ECG. The D123A mutation abrogated ECG inhibition, but actually improved ADP activation. Therefore, D123-ECG interactions may be partially to account for either the higher affinity or the inhibition. This could have an added benefit in that it would modify the purine ring such that it might not compete with ADP binding proteins. It may also be possible to modify the β-phosphate of ADP to better mimic ECG. The β-phosphate of ADP interacts with R400 and R463 but is in close proximity to D123. Perhaps an ADP analog with polar but not a phosphate moiety in that position would improve binding and allow it to inhibit like ECG. Conversely, an EGCG mimic might be made by replacing the reactive polyphenols with polar moieties that interact with the crucial residues as per the mutational studies.

Possible therapeutics for GDH-mediated insulin disorders

Because of the low ED50’s and their non-toxic nature, a major focus was placed on measuring the effects of the polyphenols on GDH in tissue and in-vivo [80]. Since EC or EGC were not active against GDH, but have the same anti-oxidant activity as ECG and EGCG, the anti-oxidant property of these catechins cannot be relevant to GDH inhibition [81]. Activity, presumably binding, is dependent upon the presence of the third ring structure, the gallate, on the flavonoid moiety. EGCG and ECG allosterically inhibit purified animal GDH in-vitro with a nanomolar ED50. EGCG inhibition is non-competitive and, similar to GTP inhibition, is abrogated by leucine, BCH, and ADP. As noted above, the antenna is necessary for GTP inhibition and ADP activation [55]. Similarly, EGCG does not inhibit the ‘antenna-less’ form of GDH, thus is further evidence that EGCG is an allosteric inhibitor. Most importantly, EGCG inhibits HHS GDH mutants as effectively as wild type [81], making it a possible therapeutic lead compound.

The next step was to ascertain whether EGCG was active in tissue. Studies have demonstrated that GDH plays a major role in leucine stimulated insulin secretion (LSIS) by controlling glutaminolysis [39, 40]. Therefore, EGCG was tested on pancreatic β-cells using the perifusion assay [81]. Importantly, EGCG, but not EGC, blocked the GDH-mediated stimulation of insulin secretion by the β-cells but did not have any effect on insulin secretion, glucose oxidation, or cellular respiration during glucose stimulation where GDH is known to not play a major role in the regulation of insulin secretion. Therefore, EGCG is indeed a specific inhibitor of GDH both in-vitro and in-situ.

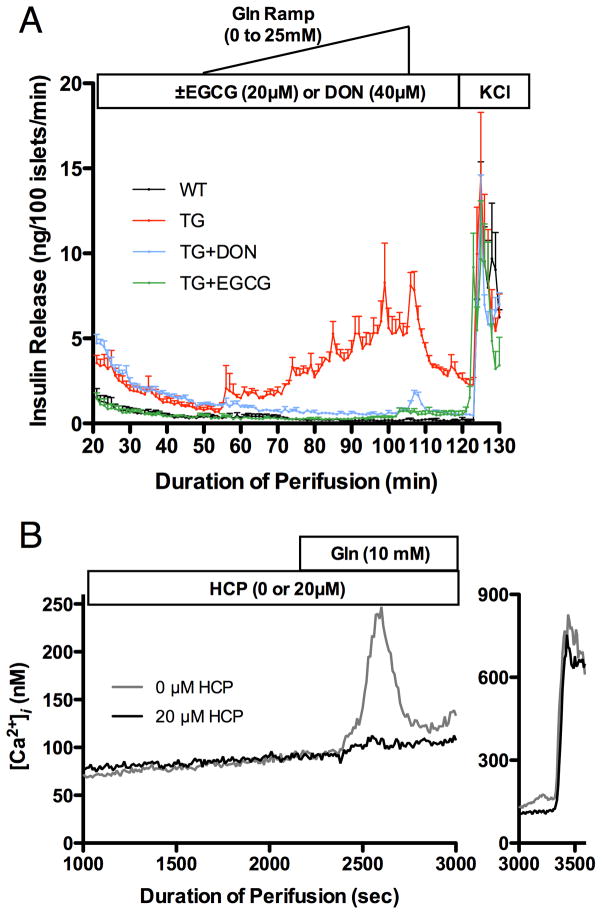

As shown in Figure 7, EGCG inhibition of GDH-mediated insulin secretion also extends to transgenic (TG) mouse tissue that expressed a gain of function of human GDH mutation, H454Y, in β-cells. As expected, the glutaminase inhibitor, DON, and EGCG are both able to block the HHS hyper-response to the addition of Gln. However, only EGCG was able to bring down the basal level of insulin release to that of WT tissue. This, in addition to the fact that DON is significantly more toxic in-vivo than EGCG [85], suggests it is possible to treat HHS in a non-toxic manner by directly targeting GDH. As shown here, EGCG does not decrease insulin levels in WT tissue. This is likely due to GDH being kept mostly in a tonic state in the pancreas and its allosteric inhibition is only alleviated when the energy state of the mitochondria is low. Indeed, the ADP/EGCG antagonism may allow for an allosteric ‘release valve’ whereby even EGCG inhibition is abrogated by ADP when the need for amino acid catabolism is strong enough. This model is further supported by the amino acid metabolism studies that measure amino acids levels in the pancreatic tissue [80]. Under glucose rich conditions, there is no significant effect of EGCG on Glu/Gln levels in either TG or WT cells. This is likely due to nearly quiescent GDH activity because of the elevated levels of GTP and ATP. However, when Gln is the major carbon source, EGCG significantly blocks Glu metabolism in TG tissue while not having significant effects on WT tissue. Under such conditions, the GDH activity is expected to increase to respond to the energy needs of the mitochondria. Since the GDH activity is much higher in TG tissue, it follows that it will be more sensitive to EGCG inhibition.

Figure 7.

Effects of EGCG and HCP on pancreatic tissue from transgenic mice expressing the HHS form of human GDH. A) A glutamine ramp stimulates insulin secretion from transgenic mice (red) but not from wild type mice (black). Administration of EGCG (green) not only blocks this hyper-response, but also decreases the base level of insulin (levels at T=0). In contrast, the glutaminase inhibitor DON (blue) blocks the hyper-response to glutamine, but does not ameliorate the higher basal serum levels of insulin. B) HCP also blocks the hyper-response to glutamine by the transgenic tissue. In this figure, the pulse of calcium signals the degranulation of the β-cells that is blocked by HCP.

While EGCG is a natural product with extremely low toxicity issues, it has several problems if it is to be used therapeutic agent [86]. It is poorly absorbed in intestinal tract, is rapidly modified by enzymes such as catechol-O-methyltransferease (COMT), and its anti-oxidant activity makes it relatively unstable in solution. To validate our findings with EGCG, the more stable GDH inhibitor, hexachlorophene (HCP), identified in our previous HTS studies [64], was also examined (Figure 7). Exactly as was found with EGCG, HCP was very effective at blocking the hyper-response to Gln in TG tissue. However, likely due its greater stability and hydrophobicity, the approximate EC50 for HCP in tissue is nearly the same as was found in-vitro with purified GDH [64]. This demonstrates the balance between stability, toxicity, and bioavailability that will need to be eventually found in developing therapeutics for HHS.

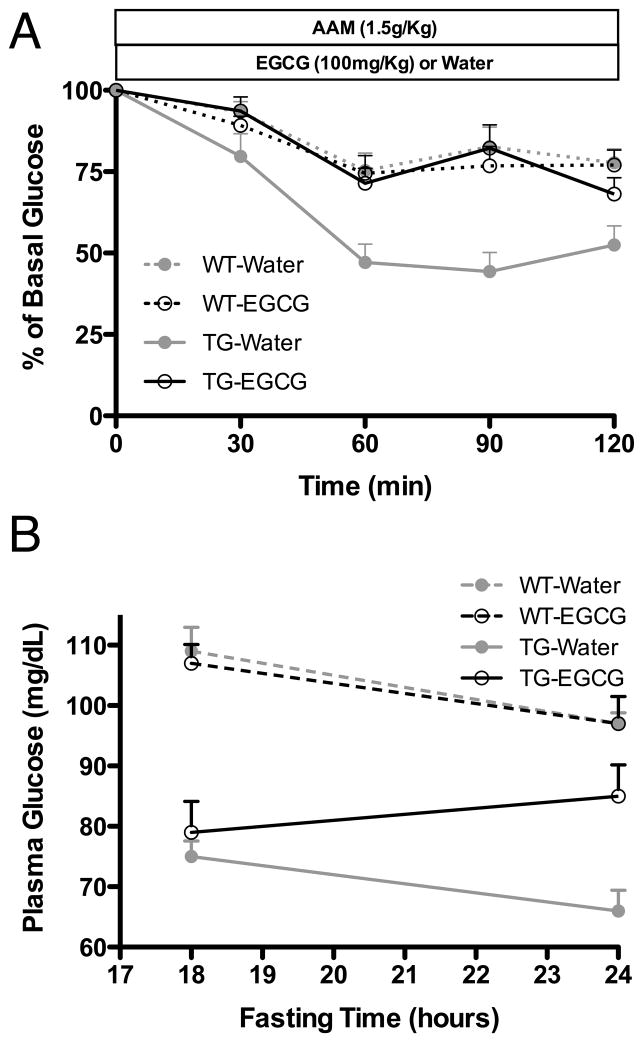

The remaining question was whether either of these lead compounds could control the HHS symptoms in the TG mice when administered orally. Due to its low toxicity, EGCG was selected for in-vivo application. An optimal drug for HHS should be able to block the hyperinsulinism response upon the consumption of amino acids as well as elevate basal serum glucose levels. As shown in Figure 8, when EGCG is orally administered before challenging the TG mice with an amino acid mixture, the GDH-mediated hyperinsulinism is blocked. In addition, as was first observed in the islet perifusion assays (Figure 7), chronic administration of EGCG during fasting improved the basal plasma glucose levels in the TG mice. Together, these results clearly demonstrate that it is possible to directly target the dysregulated form of GDH in HHS in-vivo. It remains to be seen whether such compounds can also elevate serum ammonium levels and prevent the CNS pathology caused by HHS.

Figure 8.

The effects of oral administration of EGCG on transgenic mice expressing the human HHS form of GDH. A) When transgenic mice are administered an amino acid mixture, they hyper-secrete insulin and the serum glucose levels decrease. This is not observed in wild type mice and is blocked by administration of EGCG prior to amino acid challenge. Notably, EGCG has no effect on wild type mice, and is likely indicative of the normally tonic state of GDH. B) When EGCG is administered twice during fasting, an improvement in the basal level of glucose is observed.

It is important to note that allosteric GDH inhibitors may have more applications than just treating HHS. Recent studies confirmed our observation that EGCG inhibits GDH in-situ and may be useful in treating glioblastoma [87]. In this work, EGCG was found to sensitize glioblastoma cells to glucose withdrawal and to inhibitors of Akt signaling and glycolysis. Subsequently, others demonstrated EGCG inhibition of GDH activity may be useful in treating the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) disorder [88]. Nearly all of the TSC1/2 −/− cells that were deprived of glucose and given rapamycin died upon administration of EGCG. As expected, EGCG effects were reversed if GDH mediated oxidation of glutamate was circumvented by the addition of 2-oxoglutarate, pyruvate, or aminooxyacetate. Not only do these studies validate our findings, but also demonstrate that a non-toxic GDH inhibitor could be a synergistic tool in treating tumors.

Highlights.

Animal glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) exhibits complex allosteric regulation.

Allostery likely initially evolved in response to changes in organelle function.

Allostery was subsequently refined to accommodate diverse functions in the various organs.

Allosteric regulation likely occurs by controlling protein dynamics and subunit communication.

New allosteric inhibitors can control GDH-mediated hyperinsulinism and may be useful in treating tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant DK072171 (to T.J.S.), NIH Grant DK53012 and American Diabetes Association Research Award 1-05-RA-128 (to C.A.S.), and NIH Grant DK19525 for islet biology and radioimmunoassay cores. A special thanks goes to Blue California (www.bluecal-ingredients.com) for the generous gift of EGCG used for the whole animal studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hudson RC, Daniel RM. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1993;106B:767–792. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(93)90031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frieden C. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:2028–2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George SA, Bell JE. Biochemistry. 1980;19:6057–6061. doi: 10.1021/bi00567a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey JS, Bell ET, Bell JE. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:5579–5583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwatsubo M, Pantaloni D. Bull Soc Chem Biol. 1967;49:1563–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koberstein R, Sund H. Eur J Biochem. 1973;36:545–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dieter H, Koberstein R, Sund H. Eur J Biochem. 1981;115:217–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith TJ, Schmidt T, Fang J, Wu J, Siuzdak G, Stanley CA. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:765–777. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banerjee S, Schmidt T, Fang J, Stanley CA, Smith TJ. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3446–3456. doi: 10.1021/bi0206917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yielding KL, Tomkins GM. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1961;47:983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.7.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prough RA, Culver JM, Fisher HF. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:8528–8533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahien LA, Kmiotek E. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1981;212:247–253. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomkins GM, Yielding KL, Curran JF. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:1704–1708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker PJ, Britton KL, Engel PC, Farrantz GW, Lilley KS, Rice DW, Stillman TJ. Proteins: Struct, Funct, and Gen. 1992;12:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stillman TJ, Baker PJ, Britton KL, Rice DW. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:1131–1139. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yip KSP, Stillman TJ, Britton KL, Artymiuk PJ, Baker PJ, Sedelnikova SE, Engel PC, Pasquo A, Chiaraluce R, Consalvi V, Scandurra R, Rice DW. Structure. 1995;3:1147–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson PE, Smith TJ. Structure Fold Des. 1999;7:769–782. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith TJ, Peterson PE, Schmidt T, Fang J, Stanley C. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:707–720. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson P, Pierce J, Smith TJ. J Struc Biol. 1998;120:73–77. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frieden C. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1963;10:410–415. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalziel K, Egan RR. Biochem J. 1972;126:975–984. doi: 10.1042/bj1260975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalziel K. In: The Enzymes. Boyer PD, editor. Academic Press; New York: 1975. pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell JE. Studies on negative cooperativity in glutamate dehydrogenase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Oxford University; England: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell ET, LiMuti C, Renz CL, Bell JE. Biochem J. 1985;225:209–217. doi: 10.1042/bj2250209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frieden C. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:809–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frieden C. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:815–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shafer JA, Chiancone E, Vittorelli LM, Spagnuolo C, Machler B, Antonini E. Eur J Biochem. 1972;31:166–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Limuti CM. Glutamate dehydrogenase: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Department of Biochemistry, University of Rochester; Rochester, New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koshland DE, Nemethy G, Filmer D. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–384. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koshland DEJ. Cur Opin Struc Biol. 1996;6:757–761. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalziel K, Engel PC. FEBS Lett. 1968;1:349–352. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(68)80153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wrzeszczynski KO, Colman RF. Biochemistry. 1994;33:11544–11553. doi: 10.1021/bi00204a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Batra SP, Colman RF. Biochemistry. 1986;25:3508–3515. doi: 10.1021/bi00360a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanley CA, Lieu YK, Hsu BY, Burlina AB, Greenberg CR, Hopwood NJ, Perlman K, Rich BH, Zammarchi E, Poncz M. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:1352–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sener A, Malaisse WJ. Nature. 1980;288:187–189. doi: 10.1038/288187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sener A, Malaisse-Lagae F, Malaisse WJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:5460–5464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fahien LA, MacDonald MJ, Kmiotek EH, Mertz RJ, Fahien CM. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1988;263:13610–13614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li C, Najafi H, Daikhin Y, Nissim I, Collins HW, Yudkoff M, Matschinsky FM, Stanley CA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2853–2858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li C, Buettger C, Kwagh J, Matter A, Daihkin Y, Nissiam I, Collins HW, Yudkoff M, Stanley CA, Matschinsky FM. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13393–13401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley CA. In: Genetic Insights in Paediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. O’Rahilly S, Dunger DB, editors. BioScientifica, Ltd; Bristol: 2000. pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanley CA, Fang J, Kutyna K, Hsu BYL, Ming JE, Glaser B, Poncz M. Diabetes. 2000;49:667–673. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacMullen C, Fang J, Hsu BYL, Kelly A, deLonlay-Debeney P, Saudubray JM, Ganguly A, Smith TJ, Stanley CA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1782–1787. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu BY, Kelly A, Thornton PS, Greenberg CR, Dilling LA, Stanley CA. J Pediatr. 2001;138:383–389. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bahi-Buisson N, Roze E, Dionisi C, Escande F, Valayannopoulos V, Feillet F, Heinrichs C. Dev Med & Child Neurol. 2008;50:945–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrero-Yraola A, Bakhit SM, Franke P, Weise C, Schweiger M, Jorcke D, Ziegler M. EMBO J. 2001;20:2404–2412. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R, Haigis KM, Fahie K, Christodoulou DC, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Karow M, Blander G, Wolberger C, Prolla TA, Weindruch R, Alt FW, Guarente L. Cell. 2006;126:941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hussain K, Clayton PT, Krywawych S, Chatziandreou I, Mills P, Ginbey DW, Geboers AJ, Berger R, van den Berg IE, Eaton S. J Pediatr. 2005;146:706–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson S, Bartlett K, Land J, Moxon ER, Pollitt RJ, Leonard JV, Turnbull DM. Pediatric Research. 1991;29:406–411. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199104000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molven A, Matre GE, Duran M, Wanders RJ, Rishaug U, Njolstad PR, Jellum E, Sovik O. Diabetes. 2004;53:221–227. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kapoor RR, James C, Flanagan SE, Ellard S, Eaton S, Hussain K. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;94:2221–2225. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanley C, Bennett MJ, Mayatepek E. In: Inborn metabolic diseases. Fernandes J, Saudubray J-M, van den Berg G, Walter JH, editors. Springer; Heidelberg: 2006. pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li C, Chen P, Palladino A, Narayan S, Russell LK, Sayed S, Xiong G, Chen J, Stokes D, Butt YM, Jones PM, Collins HW, Cohen NA, Cohen AS, Nissim I, Smith TJ, Strauss AW, Matschinsky FM, Bennett MJ, Stanley CA. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31806–31818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Filling C, Kelier B, Hirschberg D, Marschall H-U, Jörnvall H, Bennett MJ, Oppermann U. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2008;368:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allen A, Kwagh J, Fang J, Stanley CA, Smith TJ. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14431–14443. doi: 10.1021/bi048817i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerhardt B. Prog Lipid Res. 1992;31:417–446. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(92)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erdmann R, Veenhuis M, Kunau WH. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:400–407. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muller M, Hogg JF, De Duve C. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:5385–5395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blum JJ. J Protozool. 1973;20:688–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1973.tb03600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reddy JK, Mannaerts GP. Ann Rev Nutrition. 1994;14:343–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.002015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hashimoto T. Neurochem Res. 1999;24:551–563. doi: 10.1023/a:1022540030918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kibbey RG, Pongratz RL, Romanelli AJ, Wollheim CB, Cline GW, Shulman GI. Cell Metabolism. 2007;5:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stanley CA, Baker L. Adv Pediatr. 1976;23:315–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li M, Allen A, Smith TJ. Biochemistry. 2007;46:15089–15102. doi: 10.1021/bi7018783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hallick RB, Chelm BK, Gray PW, Orozco EMJ. Nucleic Acids Research. 1977;4:3055–3064. doi: 10.1093/nar/4.9.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benchokroun Y, Couprie J, Larsen AK. Biochem Pharm. 1995;49:305–313. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gonzalez RG, Haxo RS, Schleich T. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4299–4303. doi: 10.1021/bi00559a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sarno S, Reddy H, Meggio F, Ruzzene M, Davies SP, Donella-Deana A, Shugar D, Pinna LA. FEBS Lett. 2001;496:44–48. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skovronsky DM, Zhang B, Kung MP, Kung HF, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:7609–7614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ishikawa K, Doh-ura K, Kudo Y, Nishida N, Murakami-Kubo I, Ando Y, Sawada T, Iwaki T. J Gen VIrol. 2004;85:1785–1790. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Degterev A, Lugovskoy A, Cardone M, Mulley B, Wagner G, Mitchison T, Yuan J. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:173–182. doi: 10.1038/35055085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Calderon P, van Dorsser W, Geöcze von Szendroi K, De Mey JG, Roba J. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1986;284:101–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piccioni F, Roman BR, Fischbeck KH, Taylor JP. Human Molecular Genetics. 2004;13:437–446. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kindmark H, Köhler M, Gerwins P, Larsson O, Khan A, Wahl MA, Berggren PO. Biosci Rep. 1994;14:145–158. doi: 10.1007/BF01240247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lamers JM, Stinis JT. Cell Calcium. 1983;4:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(83)90005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fuller RW, Snoddy HD. Endocrinology. 1979;105:923–928. doi: 10.1210/endo-105-4-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miller KJ, King A, Demchyshyn L, Niznik H, Teitler M. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;227:99–102. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90149-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dodds EC, Goldberg L, Lawson W, Robinson R. Nature. 1938;141:247–248. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tomita T, Kuzuyama T, Nishiyama M. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260265. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li C, Li M, Narayan S, Matschinsky FM, Bennet MJ, Stanley CA, Smith TJ. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.268599. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li C, Allen A, Kwagh K, Doliba NM, Qin W, Najafi H, Collins HW, Matschinsky FM, Stanley CA, Smith TJ. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10214–10221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512792200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith TJ, Kremer MJ, Luo M, Vriend G, Arnold E, Kamer G, Rossmann MG, McKinlay MA, Diana GD, Otto MJ. Science. 1986;233:1286–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.3018924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith TJ, Baker TS. Adv Virus Res. 1999;52:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Katpally U, Smith TJ. J Virol. 2007;81:6307–6315. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00441-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Earhart RH, Amato DJ, Chang AY, Borden EC, Shiraki M, Dowd ME, Comis RL, Davis TE, Smith TJ. Invest New Drugs. 1990;8:113–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00216936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smith TJ. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 2011;6:589–595. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.570750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang C, Sudderth J, Dang T, Bachoo RG, McDonald JG, DeBerardinis RJ. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7986–7993. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Choo AY, Kim SG, Vander Heiden MG, Mahoney SJ, Vu H, Yoon SO, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Molecular Cell. 2010;38:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]