Abstract

Ciliated epithelia are important in a wide variety of biological contexts where they generate directed fluid flow. Here we address the fundamental advances in understanding ciliated epithelia that have been achieved using Xenopus as a model system. Xenopus embryos are covered with a ciliated epithelium that propels fluid unidirectionally across their surface. The external nature of this tissue, coupled with the molecular tools available in Xenopus and the ease of microscopic analysis on intact animals has thrust Xenopus to the forefront of ciliated epithelia biology. We discuss advances in understanding the molecular regulators of ciliated epithelia cell fate as well as basic aspects of ciliated epithelia cell biology including ciliogenesis and cell polarity.

Keywords: Xenopus, cilia, ciliogenesis, planar cell polarity, cell fate specification

Cilia have recently risen to the forefront of both cell and developmental biology due to the discovery of their involvement in a wide range of signaling events. Cilia are much more prevalent than thought a decade ago and it is now generally appreciated that most post mitotic vertebrate cells contain a cilium. Additionally, a combination of proteomic, genomic and genetic studies have identified a variety of ciliopathies, a set of pleiotrophic diseases that are linked by cilia dysfunction (Avidor-Reiss et al., 2004; Badano et al., 2006; Li et al., 2004). While much of the ciliopathy related research has focused on non-motile sensory cilia, motile cilia have increasingly gained interest due to their involvement in the generation of directed fluid flow that is essential for a variety of developmental and physiological processes. During development, cilia driven fluid flow in the ventricles is essential for proper neuroblast migration (Sawamoto et al., 2006). A leftward driven fluid flow in the embryonic node is responsible for determining the left right axis of organ development (Nonaka et al., 1998). During the female reproductive cycle, cilia driven flow in the fallopian tubes fluctuates reaching peak flow when the egg begins migrating towards the uterus (Hagiwara et al., 1992). Finally, in the respiratory tract, cilia driven mucus flow is responsible for clearing bacteria and debris from the lungs as the first line of defense against infection (Meeks and Bush, 2000). The common feature of these processes is that the cilia generated fluid flow must be unidirectional along the planar axis of the tissue. The loss of this directed flow in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesa, also known as immotile cilia syndrome or Kartageners, results in a wide range of problems including hydrocephaly, situs inversus, infertility and severe respiratory dysfunction.

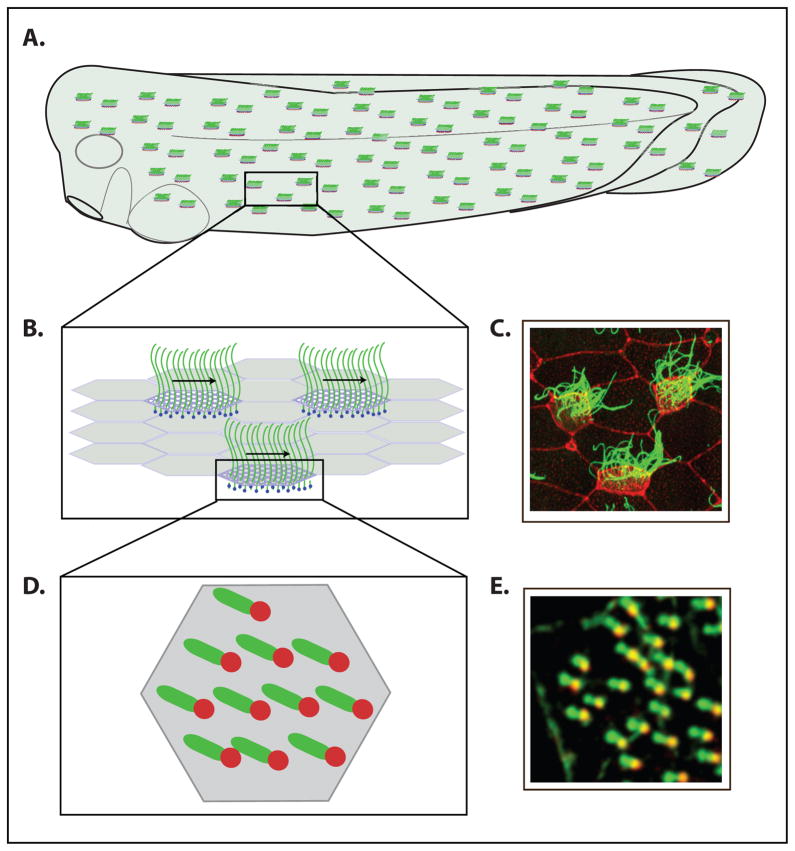

Ciliated epithelia are prevalent throughout nature, performing both locomotor functions in a variety of aquatic organisms and providing directed fluid flow in a number of developmental and physiological contexts. Single cell ciliates, such as Chlamydomonas and Tetrahymena have provided a wealth of biochemical and structural information regarding cilia but studies in these organisms are limited in terms of understanding the polarity of multicellular ciliated epithelia. As mentioned above, mammals have a variety of ciliated epithelia, however, the internal nature of these tissues provides a number of challenges, limiting the ability to follow the developmental progression and dynamics of cilia formation and function. Over the last several years a number of groups have worked to develop the ciliated epithelia of Xenopus embryonic skin as a model system for understanding the development of ciliated cells and their ability to generate directed fluid flow. Xenopus embryos respire through their skin and cilia driven fluid flow is thought to be critical to continually replenish oxygenated water. The ciliated epithelia of Xenopus skin develops quickly, such that fully oriented cilia are capable of generating a robust and invariably directed fluid flow within days of fertilization. In order to generate robust flow ciliated cells must be polarized relative to each other within the tissue and individual cilia must be polarized relative to each other within a given cell (Figure 1). The molecular, genetic and embryological tools available in Xenopus combined with the speed of development and the ease of microscopic analysis on intact animals have demonstrated that Xenopus is an ideal system to address issues of cilia function. In this review we will take an in depth view of the advances in understanding ciliated epithelia that have been fostered via the use of Xenopus as a model system. While this review will focus exclusively on Xenopus, it is not our intention to downplay or ignore the significance of work in other systems but merely to highlight the work in Xenopus.

Figure 1.

The Xenopus embryo: a model system for studying multi-ciliated epithelia. (A.) Image of a Xenopus embryo showing the punctuate pattern of ciliated cells that cover the surface. (B.) Enlarged inlay of (A.) indicating that individual ciliated cells must be coordinately polarized. (C.) Xenopus embryo stained with anti Beta-tubulin antibody to mark the cilia (green) and Rhodamine labeled phalloidin to mark actin (Red). (D.) Enlarged inlay of (B.) indicating that individual cilia must be coordinately polarized within each ciliated cell. (E.) Portion of a cell from a Xenopus embryo injected with the basal body marker, Centrin-RFP (red) and the rootlet marker GFP-CLAMP (green) which is used to score the orientation of individual cilia (Park et al., 2008).

The first burst of research into vertebrate ciliary biology occurred in the 1830’s when a handful of anatomists including the famous Purkyny and Valantine observed ciliary flow in the fallopian tubes of rabbits (Valantine and Purkyny 1834, as translated by Sharpey 1835) (Sharpey, 1835). In fact as early as 1830 William Sharpey had observed directed fluid motions on the surface of amphibian embryos which he cautiously likened to observations in invertebrates where “the motion in the fluid is produced by the mere agitation of the cilia” (Sharpey, 1830). These initial observations were later expanded upon by Richard Assheton, who in 1895 published his “Notes on the Ciliation of the Ectoderm of the Amphibian Embryo” which detailed the directed cilia driven fluid flow on the surface of amphibian embryos (Assheton, 1896). By the 1920s, observations turned into experimental biology as Woerdeman (1925) and Twitty (1928) began performing skin transplant experiments to determine the timing and robustness of ciliated tissue polarity (Twitty, 1928; Woerdeman, 1925). However, it was not until the early part of this century that the molecular regulators of ciliogenesis and cilia polarity began to be investigated in detail.

Regulation of Ciliated Epithelial Cell Fate

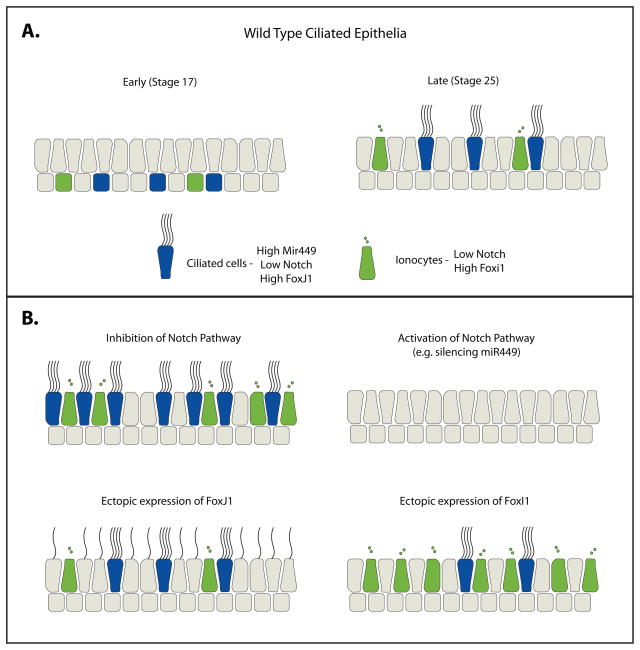

The skin of Xenopus embryos has been particularly useful in determining the molecular regulation of ciliated cell fate. Ciliated cell precursors initially reside in a distinct sublayer of the epidermis. As they begin to differentiate they migrate apically and undergo a process of radial intercalation by which they join the outer epithelium and undergo ciliogenesis (Figure 2A)(Stubbs et al., 2006). The punctate pattern of ciliated cells on the surface of the Xenopus ectoderm is striking in that two ciliated cells almost never develop next to one another. This pattern hinted at a mechanism similar to Notch driven lateral inhibition of neuroblast specification (Cabrera, 1990; Chitnis et al., 1995). Activation of the Notch pathway does indeed lead to a severe decrease in ciliated cells that differentiate in the sub-epidermal layer, whereas blocking Notch results in a significant increase in ciliated cells (Figure 2B)(Stubbs et al., 2006). However, while this suggests that ciliated cell fate specification is regulated by Notch signaling it appears that the punctate pattern actually stems from limitations of cell intercalation rather then a lateral inhibition mechanism per se (Stubbs et al., 2006). Ciliated cells only intercalate at the junction of a pre-existing 3–4 cell vertices, thereby limiting the number of cells that intercalate and insuring that two ciliated cells will not be adjoining (Stubbs et al., 2006).

Figure 2.

The differentiation of Xenopus ciliated epithelium. (A.) Ciliated cell and ionocyte precursors reside in a sub-layer of the epidermis at stage 17 and undergo radial intercalation to join the outer epidermis by stage 25. (B.) Regulation of cell fate in the skin of Xenopus. Inhibition of the Notch pathway leads to an increase in ciliated cell and ionocyte differentiation. Activation of the Notch pathway, by silencing miR449 for example, leads to a severe decrease in ciliated cells. Ectopic expression of FoxJ1 leads to outer epithelial cells that are capable of generating 1–2 motile cilia. Ectopic expression of FoxI1 leads to an increase in ionocytes.

The Notch pathway often acts as a negative regulator of particular cell fates by turning on transcriptional repressors of the bHLH family. In the case of ciliated cells Notch turns on the WRPW-bHLH protein Enhancer of Split-6e (ESR6e), which in turn represses ciliated cell fate (Deblandre et al., 1999). Interestingly, a recently published paper reports that Notch regulation of ciliated cells is itself regulated by the microRNA miR-449, which specifically targets and blocks transcription of both the Notch receptor and its ligand Dll1 (Marcet et al., 2011). Silencing of miR-449 leads to an increase in Dll1, increased activation of the Notch pathway, and a decrease in ciliated cell differentiation (Figure 2B) (Marcet et al., 2011).

Ciliated epithelia are complex tissues comprised of multiple cell types. To date, the most prominently studied cells in the Xenopus ciliated epithelia have been the ciliated cells. However, recently several groups have begun to look at another fascinating cell type, the ionocytes (Dubaissi and Papalopulu, 2010; Quigley et al., 2011). Ionocytes are proton-secreting cells that, similar to ciliated cells, arise in the sub-epithelial layer and intercalate into the outer layer. These cells are also regulated by Notch signaling and a member of the Fox family of transcription factors FoxI1 (Figure 2B) (Dubaissi and Papalopulu, 2010; Quigley et al., 2011). This population of ionocytes can be further subdivided based on the expression of specific ion channels into two classes resembling the alpha- and beta-intercalated cells of the kidney (Quigley et al., 2011). Remarkably, transplantation of skin devoid of ionocytes onto wild type tissue leads to ciliogenesis defects in the neighboring wild type ciliated cells, suggesting that these cells secrete an unknown factor that disrupts ciliogenesis in a non-cell autonomous manner (Dubaissi and Papalopulu, 2010). Clearly, Xenopus will continue to be a powerful system to address the interactions of this complex epithelium.

Regulation of Ciliogenesis

In addition to Notch signaling which drives ciliated cell differentiation, the transcription factor FoxJ1 is specifically involved in turning on genes required to make motile cilia (Stubbs et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2008). A microarray analysis in Xenopus of genes upregulated by FoxJ1 identified a number of genes that encode either known motile cilia proteins such as axonemal dynein or proteins identified through proteomics approaches to be part of the ciliome (Stubbs et al., 2008). Additionally, an in situ hybridization based screen of randomly selected cDNAs has led the identification of a number of genes expressed specifically in either ciliated cells, the neighboring ion-secreting cells, or mucus secreting cells (Hayes et al., 2007). Both these approaches highlight the usefulness of Xenopus epithelium as a tool to identify novel genes involved in ciliogenesis.

A unique and important aspect of multiciliated cells is their ability to undergo massive centriole duplication generating the approximately 100 basal bodies (centrioles) that nucleate the cilia. In most cell types centriole duplication is tightly regulated and linked to the cell cycle (Lacey et al., 1999). The mechanism by which ciliated cells uncouple centriole duplication from the cell cycle is unknown, however, it requires the presence of a molecularly uncharacterized structure termed the deuterosome that has only been described at the level of electron microscopy (Steinman, 1968). Importantly, centriole duplication does not appear to be regulated either by Notch or by FoxJ1. In fact, cells ectopically expressing both activated Notch and FoxJ1 fail to undergo centriole duplication, but rather use the existing centrioles to make 1 or 2 motile cilia reminiscent of the motile mono cilium at the gastrocoel roof plate (GRP), the Xenopus equivalent of the embryonic node (Figure 2B) (Stubbs et al., 2008). Since ectopic expression of FoxJ1 is insufficient to drive formation of multiple centrioles it is likely that other important factors will be identified that are involved in the transcriptional regulation of this complicated aspect of multiciliated cell fate.

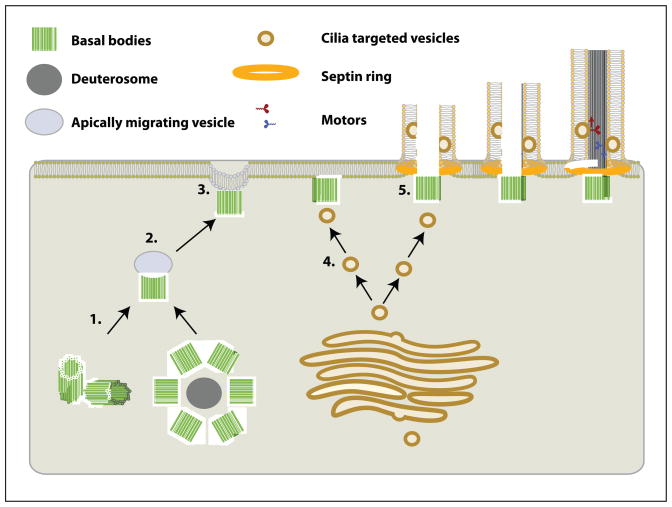

Ciliogenesis in multiciliated cells is a complex process requiring a variety of steps (Figure 3). After centriole duplication, individual basal bodies migrate apically, where they dock with the apical cell membrane. Vesicle trafficking then promotes the delivery of ciliary components to the apically docked basal bodies allowing the assembly of the ciliary axoneme. One of the more striking breakthroughs discovered regarding the development of ciliated epithelia is that members of the non-canonical Wnt or Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) pathway are involved in the process of ciliogenesis. The PCP pathway is generally involved in providing polarity cues during tissue polarization (discussed below), however, PCP components must be localized to the apical cell domain prior to driving planar polarity. It is therefore likely that basal bodies co-opt some aspect of the PCP apical localization machinery to facilitate fusion with the apical cell membrane. In fact the core intracellular PCP component Disheveled (Dvl) promotes fusion of basal bodies to apically targeted vesicles (Figure 3, step 2 and 3)(Park et al., 2008). In the absence of functional Dvl, basal bodies still duplicate but fail to fuse with the apical membrane thereby preventing normal ciliogenesis (Park et al., 2008). Since basal bodies can sometimes still nucleate axonemes intracellularly the observed ciliogenesis defect is likely due to the lack of apical migration of basal bodies rather than defects in cilia assembly (personal observation). Similar to Dvl, the downstream PCP effector Inturned (Intu) appears to be involved in apical targeting of basal bodies since depletion of Intu also blocks the ability of basal bodies to dock with the apical membrane (Figure 3, step 3)(Park et al., 2006).

Figure 3.

Steps of ciliogenesis in multiciliated cells. A simplified diagram of ciliogenesis that includes centriole duplication (1), fusion of basal bodies to apically migrating vesicles (2), docking with the apical membrane (3), targeting of cilia components to the basal body and ciliary membrane (4), and axoneme elongation (5).

The depletion of another core PCP component, Van Gogh Like-2 (Vangl2), also leads to ciliogenesis defects that are likely due to defects in basal body apical migration (Mitchell et al., 2009). Vangl2 morphant cells typically do make some cilia but fail to make the proper numbers (Mitchell et al., 2009). Perhaps somewhat telling, monociliated cells in the GRP, which only need to apically localize one cilium do not have ciliogenesis defects in Vangl2 morphants (Antic et al., 2010). This difference may indicate the cellular challenge of driving such large numbers of basal bodies to the apical surface, however, these observations are difficult to interpret given that the mechanism of action for Vangl2 in the process is still unknown.

Morphants of the well characterized downstream PCP effector Fuzzy (Fuz), also exhibit strong ciliogenesis defects. In contrast to Dvl, Vangl2 and Intu, Fuz appears to be required for apical targeting of secretory vesicles rather than apical targeting of basal bodies. In fact, Fuz localizes to secretory vesicles together with the small GTPase RSG1 and depletion of Fuz in ciliated cells results in a loss of vesicle targeting to the apically fused basal bodies (Figure 3, step 4)(Gray et al., 2009). The targeting of cilia bound proteins via directed vesicle transport has emerged as a major component of cilia function in primary cilia (For review see (Nachury et al., 2010)). It will be interesting to see if these diverse mechanisms that have been uncovered in primary cilia formation are conserved in motile cilia.

Finally, one more PCP effector, Fritz, has been implicated in yet another aspect of ciliogenesis (Kim et al., 2010). Two recent studies have shown that septins form a distinct ring around the base of both primary and motile cilia and this has been proposed to act as a diffusion barrier, limiting the passage of membrane bound proteins into and out of the cilium (Figure 3, step 4 and 5) (Hu et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010). Fritz physically interacts with septins and depletion of Fritz leads to a loss of apical localization of septins while both Fritz and septin morphants exhibit ciliogenesis defects (Kim et al., 2010). These data therefore suggest that Fritz affects ciliogenesis by promoting the formation of an apical septin ring at the base of motile cilia thereby regulating the protein composition of the ciliary membrane.

While Xenopus has been a fruitful system for the analysis of PCP components and ciliogenesis, it is comforting to know that many of the same defects, as well as other cilia related defects due to loss of other PCP components, have now been observed in mouse and zebrafish (Gray et al., 2009; May-Simera et al., 2010; Tissir et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2010). The observed phenotypes implicate components of the PCP pathway in ciliogenesis, however, they do so in subtly different ways such as blocking basal body apical migration or basal body fusion with the apical membrane. Consequently, a clear mechanism for how diverse components of the PCP pathway can lead to ciliogenesis defects has yet to emerge. It is possible that these observations are related to independent protein co-option events rather then the co-option of the pathway at large. The interest in both PCP signaling and cilia ensures that these question will continue to be the subject of significant future research.

The Planar Polarization of Cilia

The ability of ciliated epithelia to generate directed fluid flow indicates that the cells are polarized within the plane of the tissue, a feature known as PCP. PCP has been studied in great detail in Drosophila where the first genes were identified that affected the orientation of hair cells in the wing (Gubb and Garcia-Bellido, 1982). In particular, components of the non-canonical Wnt or PCP pathway have been implicated in Drosophila (and Vertebrate) PCP (For review see (Goodrich and Strutt, 2011)). What has made Drosophila such an excellent model for studying PCP signaling is the presence of a single actin based hair that projects out of many cells both on the wing and in the abdomen, thus providing an overt marker for a cell’s orientation. While it is clear that a wide variety of vertebrate epithelia require PCP signaling to function properly the lack of obviously polarized structures has limited the cell types that have been studied in detail. The oriented beating of motile cilia and their ability to generate directed flow has provided a novel experimentally tractable system for the analysis of PCP in vertebrates. Xenopus benefits from facile methods of introducing fluorescently tagged proteins that allow scoring of polarity of individual cilia as well as cell polarity, as defined by the mean polarity of all the cilia within a cell (Figure 1). Additionally, embryological manipulations such as embryo-to-embryo skin transplants allows for a detailed analysis of the timing and molecular regulators of cell polarity (Figure 4A).

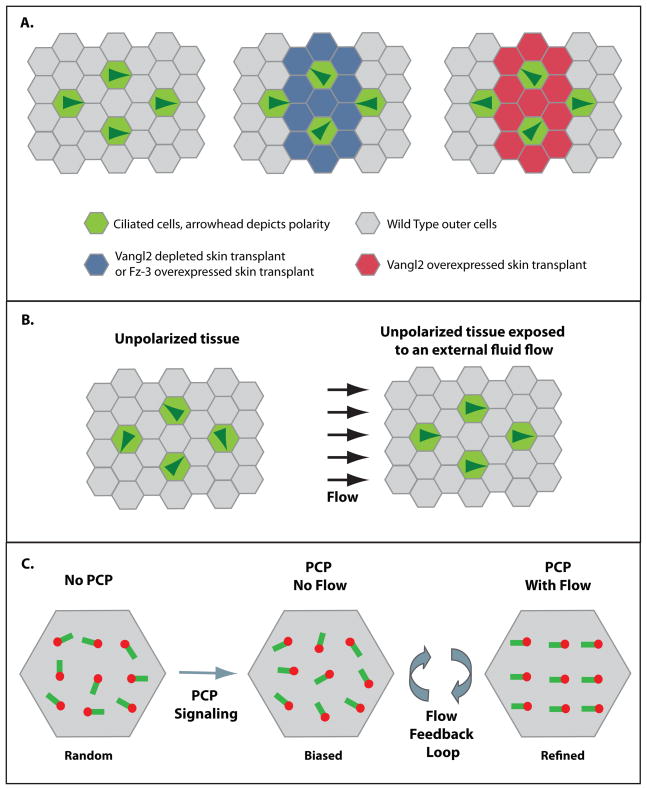

Figure 4.

The planar polarity of motile cilia in multiciliated cells. (A.) Diagram of the non-cell autonomous effect of the PCP pathway. Wild type cells direct their cilia in the posterior direction (left, arrowheads represent cell polarity). Wild type ciliated cells abutting mutant clones are instructively oriented towards low levels of Vangl2, or high levels of Fz-3 (middle) and away from high levels of Vangl2 (right). (B.) Externally applied fluid flow is sufficient to orient motile cilia. (C.) Model for two step process driving cilia polarity. PCP signaling cues weakly bias the orientation of motile cilia, thus initiating a positive feedback loop in which cilia both generate flow as well as reorient in response to the prevailing flow (Basal bodies are red and rootlets are green).

There are a large number of proteins that impinge on various aspects of the PCP pathway, but in general the pathway can be broken down into two main processes, cell-cell signaling and downstream cellular organization. Both processes can be studied in the skin of Xenopus where multiciliated cells must coordinate the orientation of cilia beating between all ciliated cells in the tissue (tissue level polarity, Figure 1B) thus allowing for detailed analysis of cell-cell signaling. Additionally, ciliated cells must integrate polarity information on the cellular level to coordinate the orientation of dozens of cilia to beat in the same direction (rotational polarity, Figure 1D,E), thus allowing for a detailed analysis of cellular organization.

For PCP to function properly, cell–cell interactions of transmembrane proteins such as Frizzled (Fz) and Vangl2 (among others), are required to coordinate the orientation of neighboring cells. In ways that are not yet fully understood these signaling events require asymmetry in localization or activity such that a given cell can interpret the “amount” of PCP activity on one side of the cell versus the other and can orient itself based on this asymmetry. In fact, many PCP signaling molecules are capable of domineering non-cell autonomous instructive signaling (Goodrich and Strutt, 2011; Vinson and Adler, 1987). This is based on analysis of mutant clones in Drosophila where at the boundary of wild type cells and the mutant clone there is a predictable imbalance of PCP signaling. In these experiments, wild type cells bordering mutant clones are not disorganized but are instructively reoriented towards or away from the clone depending on the genotype of the mutant clone (Goodrich and Strutt, 2011). While domineering non-autonomy has been a well characterized aspect of PCP in Drosophila for many years, it was only recently shown to occur in vertebrates. Using skin transplants from mRNA or morpholino injected Xenopus embryos onto wild-type host embryos to generate mutant “clones” it was determined that both Vangl2 and Fz-3 can instruct tissue level polarity of ciliated cells. Wild type cells bordering mutant clones orient the beating of their cilia towards lower levels of Vangl2 and higher levels of Fz-3 (Figure 4A) (Mitchell et al., 2009).

The relationship between cellular organization and PCP signaling remains a challenging obstacle to understanding cellular polarity. Disheveled (Dvl) was one of the first identified components of the PCP pathway, yet it is an intracellular protein that does not exhibit domineering non-cell autonomy (Mitchell et al., 2009). In fact, Dvl is downstream of the PCP signaling molecule Fz and is involved in interpreting polarity cues and coordinating the cytoskeletal rearrangements that lead to cellular organization. Dvl localizes asymmetrically at the basal bodies of cilia and overexpression of a PCP defective dominant negative version of the protein leads to a breakdown in rotational polarity (Park et al., 2008). It therefore appears that while cell-cell signaling via Vangl2 and Fz-3 instructs tissue level polarity, intracellular Dvl interprets those signals to promote cellular organization in a cell autonomous manner (Mitchell et al., 2009; Park et al., 2008).

How Dvl interprets these PCP signals and how they are translated into cellular organization is not entirely clear. Dvl has been shown to physically interact with the protein inversin (Invs) which was proposed to act as a molecular switch between canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling (Simons et al., 2005). In an analysis of non-ciliated cells, Invs was shown to facilitate Dvl co-localization with Fz at the cell membrane, again implicating it in PCP (Lienkamp et al., 2010). One possibility is that interactions between Invs and Dvl are responsible for regulating cytoskeletal interactions involved in organizing cilia polarity. In support of this idea, Invs can interact with the anaphase promoting complex (APC/C) which has been reported to localize at the basal body and has been shown to promote degradation of Dvl (Ganner et al., 2009). Interestingly, depletion of APC/C leads to defects in cilia polarity, presumably through dysregulation of Dvl (Ganner et al., 2009). Whether this dysregulation is due to an increase in Dvl protein levels or a modification of Dvl activity remains to be determined.

Downstream of Dvl the small GTPase RhoA gets activated specifically at the basal body coincident with the developmental window during which cilia rotational polarity is established. Additionally, disruption of RhoA activity leads to defects in cilia polarity. Furthermore, RhoA has been shown to regulate the organization of the apical actin cytoskeleton in multiciliated cells thereby potentially providing a link between PCP signaling, cilia polarity and the cytoskeleton (Pan et al., 2007; Panizzi et al., 2007).

In addition to the effect of PCP signaling on cilia polarity, it has been shown that in Xenopus motile cilia can themselves respond to a prevailing fluid flow (Mitchell et al., 2007). The model that has emerged is that multiciliated cells acquire polarity cues from the neighboring “outer” cells via PCP signaling, but that these polarity cues are only sufficient to weakly bias the mean orientation of cilia within a cell (Figure 4C)(Mitchell et al., 2009). This bias allows cilia to generate a weakly directed flow that establishes a positive feedback loop in which cilia both generate fluid flow and respond to it by refining their orientation (Mitchell et al., 2007). The feedback loop continues until precise polarity is achieved and vigorous fluid flow is established (Figure 4C). Interestingly, immotile cilia, incapable of generating flow are still biased in the correct direction, due to proper PCP cues, but fail to initiate the feedback loop and therefore remain frozen in the immature unrefined state (Mitchell et al., 2007). In contrast, explanted tissue that lacks polarity can be rescued by the addition of an externally applied flow (Figure 4B)(Mitchell et al., 2007). These results indicate that PCP signaling and fluid flow conspire to provide the polarity cues necessary to accomplish refined rotational polarity (Figure 4C). How then does the cell integrate these cues to drive cilia polarity?

Both actin and microtubules form elaborate connections at the apical surface of ciliated cells weaving individual basal bodies into a complex network (Werner et al., 2011). It is therefore tempting to speculate that fluid flow integrates with PCP signaling components to regulate RhoA activity at basal bodies and to promote organization of the cellular actin cytoskeleton leading to the establishment of rotational polarity. However, the loss of actin dynamics leads to a slightly different phenotype than either the disruption of Dvl or RhoA, where overall polarity is disrupted but local order between neighboring cilia is maintained (Werner et al., 2011). In contrast, loss of cytoplasmic microtubule dynamics results in a phenotype indistinguishable from disruption of Dvl or RhoA where local order is completely abolished (Werner et al., 2011). Does fluid flow, Dvl and RhoA therefore regulate cytoplasmic microtubule dynamics in addition to or instead of actin? Certainly understanding how these molecular components fit together to regulate cilia polarity will require a level of analysis that can currently best be achieved in Xenopus. While the current model provides fundamental features to the generation of cilia polarity, it also highlights the complexity of coordinating organized cellular polarity in a multi-faceted tissue.

Concluding remarks

The past 10 years have been a remarkable decade for Xenopus biology. The combination of morpholino based protein depletion and high resolution imaging on intact animals has afforded the opportunity to address fundamental questions in both development and cell biology. These advances have been particularly influential in the field of cilia biology to help better understand the generation and function of ciliated epithelia. As we endeavor to explore ciliated epithelia in more molecular detail it is exciting to speculate on the continued success of Xenopus as a model system.

Acknowledgments

BJM is funded from the NIH/NIGMS : R01GM089970

We would like to thank Jennifer Stubbs and members of the Mitchell lab for helpful comments and discussions. MEW is supported by postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association and BJM is funded through the support of the NIH/NIGMS.

References

- Antic D, Stubbs JL, Suyama K, Kintner C, Scott MP, Axelrod JD. Planar cell polarity enables posterior localization of nodal cilia and left-right axis determination during mouse and Xenopus embryogenesis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assheton R. Notes on the ciliation of the ectoderm of the amphibian embryo. QJ Microscope Sci. 1896;38:465–484. [Google Scholar]

- Avidor-Reiss T, Maer AM, Koundakjian E, Polyanovsky A, Keil T, Subramaniam S, Zuker CS. Decoding cilia function: defining specialized genes required for compartmentalized cilia biogenesis. Cell. 2004;117:527–539. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N. The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera CV. Lateral inhibition and cell fate during neurogenesis in Drosophila: the interactions between scute, Notch and Delta. Development. 1990;110:733–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis A, Henrique D, Lewis J, Ish-Horowicz D, Kintner C. Primary neurogenesis in Xenopus embryos regulated by a homologue of the Drosophila neurogenic gene Delta. Nature. 1995;375:761–766. doi: 10.1038/375761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblandre GA, Wettstein DA, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Kintner C. A two-step mechanism generates the spacing pattern of the ciliated cells in the skin of Xenopus embryos. Development. 1999;126:4715–4728. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubaissi E, Papalopulu N. Embryonic frog epidermis: a model for the study of cell-cell interactions in the development of mucociliary disease. Dis Model Mech. 2010 doi: 10.1242/dmm.006494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganner A, Lienkamp S, Schafer T, Romaker D, Wegierski T, Park TJ, Spreitzer S, Simons M, Gloy J, Kim E, Wallingford JB, Walz G. Regulation of ciliary polarity by the APC/C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17799–17804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909465106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich LV, Strutt D. Principles of planar polarity in animal development. Development. 2011;138:1877–1892. doi: 10.1242/dev.054080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RS, Abitua PB, Wlodarczyk BJ, Szabo-Rogers HL, Blanchard O, Lee I, Weiss GS, Liu KJ, Marcotte EM, Wallingford JB, Finnell RH. The planar cell polarity effector Fuz is essential for targeted membrane trafficking, ciliogenesis and mouse embryonic development. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1225–1232. doi: 10.1038/ncb1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubb D, Garcia-Bellido A. A genetic analysis of the determination of cuticular polarity during development in Drosophila melanogaster. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1982;68:37–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara H, Shibasaki S, Ohwada N. Ciliogenesis in the human oviduct epithelium during the normal menstrual cycle. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 1992;41:321–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JM, Kim SK, Abitua PB, Park TJ, Herrington ER, Kitayama A, Grow MW, Ueno N, Wallingford JB. Identification of novel ciliogenesis factors using a new in vivo model for mucociliary epithelial development. Dev Biol. 2007;312:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Milenkovic L, Jin H, Scott MP, Nachury MV, Spiliotis ET, Nelson WJ. A septin diffusion barrier at the base of the primary cilium maintains ciliary membrane protein distribution. Science. 2010;329:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.1191054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Shindo A, Park TJ, Oh EC, Ghosh S, Gray RS, Lewis RA, Johnson CA, Attie-Bittach T, Katsanis N, Wallingford JB. Planar cell polarity acts through septins to control collective cell movement and ciliogenesis. Science. 2010;329:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1191184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey KR, Jackson PK, Stearns T. Cyclin-dependent kinase control of centrosome duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2817–2822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JB, Gerdes JM, Haycraft CJ, Fan Y, Teslovich TM, May-Simera H, Li H, Blacque OE, Li L, Leitch CC, Lewis RA, Green JS, Parfrey PS, Leroux MR, Davidson WS, Beales PL, Guay-Woodford LM, Yoder BK, Stormo GD, Katsanis N, Dutcher SK. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell. 2004;117:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienkamp S, Ganner A, Boehlke C, Schmidt T, Arnold SJ, Schafer T, Romaker D, Schuler J, Hoff S, Powelske C, Eifler A, Kronig C, Bullerkotte A, Nitschke R, Kuehn EW, Kim E, Burkhardt H, Brox T, Ronneberger O, Gloy J, Walz G. Inversin relays Frizzled-8 signals to promote proximal pronephros development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20388–20393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013070107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcet B, Chevalier B, Luxardi G, Coraux C, Zaragosi LE, Cibois M, Robbe-Sermesant K, Jolly T, Cardinaud B, Moreilhon C, Giovannini-Chami L, Nawrocki-Raby B, Birembaut P, Waldmann R, Kodjabachian L, Barbry P. Control of vertebrate multiciliogenesis by miR-449 through direct repression of the Delta/Notch pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:693–699. doi: 10.1038/ncb2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May-Simera HL, Kai M, Hernandez V, Osborn DP, Tada M, Beales PL. Bbs8, together with the planar cell polarity protein Vangl2, is required to establish left-right asymmetry in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2010;345:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks M, Bush A. Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;29:307–316. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(200004)29:4<307::aid-ppul11>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell B, Jacobs R, Li J, Chien S, Kintner C. A positive feedback mechanism governs the polarity and motion of motile cilia. Nature. 2007;447:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature05771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell B, Stubbs JL, Huisman F, Taborek P, Yu C, Kintner C. The PCP pathway instructs the planar orientation of ciliated cells in the Xenopus larval skin. Curr Biol. 2009;19:924–929. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury MV, Seeley ES, Jin H. Trafficking to the Ciliary Membrane: How to Get Across the Periciliary Diffusion Barrier? Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka S, Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Takeda S, Harada A, Kanai Y, Kido M, Hirokawa N. Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell. 1998;95:829–837. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, You Y, Huang T, Brody SL. RhoA-mediated apical actin enrichment is required for ciliogenesis and promoted by Foxj1. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1868–1876. doi: 10.1242/jcs.005306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizzi JR, Jessen JR, Drummond IA, Solnica-Krezel L. New functions for a vertebrate Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor in ciliated epithelia. Development. 2007;134:921–931. doi: 10.1242/dev.02776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TJ, Haigo SL, Wallingford JB. Ciliogenesis defects in embryos lacking inturned or fuzzy function are associated with failure of planar cell polarity and Hedgehog signaling. Nat Genet. 2006;38:303–311. doi: 10.1038/ng1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TJ, Mitchell BJ, Abitua PB, Kintner C, Wallingford JB. Dishevelled controls apical docking and planar polarization of basal bodies in ciliated epithelial cells. Nat Genet. 2008;40:871–879. doi: 10.1038/ng.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley IK, Stubbs JL, Kintner C. Specification of ion transport cells in the Xenopus larval skin. Development. 2011;138:705–714. doi: 10.1242/dev.055699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto K, Wichterle H, Gonzalez-Perez O, Cholfin JA, Yamada M, Spassky N, Murcia NS, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Marin O, Rubenstein JL, Tessier-Lavigne M, Okano H, Alvarez-Buylla A. New neurons follow the flow of cerebrospinal fluid in the adult brain. Science. 2006;311:629–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1119133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpey W. On a peculiar motion excited in Fluids by the surfaces of certain Animals. Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal CIV. 1830:113–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpey W. Account of the Discovery by Purkinje and Valentin of Ciliary motions in Reptiles and Warm blooded animals. In: Jameson R, editor. Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. Edinburgh: Neill and Company; 1835. pp. 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Simons M, Gloy J, Ganner A, Bullerkotte A, Bashkurov M, Kronig C, Schermer B, Benzing T, Cabello OA, Jenny A, Mlodzik M, Polok B, Driever W, Obara T, Walz G. Inversin, the gene product mutated in nephronophthisis type II, functions as a molecular switch between Wnt signaling pathways. Nat Genet. 2005;37:537–543. doi: 10.1038/ng1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman RM. An electron microscopic study of ciliogenesis in developing epidermis and trachea in the embryo of Xenopus laevis. Am J Anat. 1968;122:19–55. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001220103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs JL, Davidson L, Keller R, Kintner C. Radial intercalation of ciliated cells during Xenopus skin development. Development. 2006;133:2507–2515. doi: 10.1242/dev.02417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs JL, Oishi I, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Kintner C. The forkhead protein Foxj1 specifies node-like cilia in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1454–1460. doi: 10.1038/ng.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissir F, Qu Y, Montcouquiol M, Zhou L, Komatsu K, Shi D, Fujimori T, Labeau J, Tyteca D, Courtoy P, Poumay Y, Uemura T, Goffinet AM. Lack of cadherins Celsr2 and Celsr3 impairs ependymal ciliogenesis, leading to fatal hydrocephalus. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:700–707. doi: 10.1038/nn.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twitty VC. Experimental studies on the ciliary action of amphibian embryos. J Exp Zool. 1928;50:310–344. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson CR, Adler PN. Directional non-cell autonomy and the transmission of polarity information by the frizzled gene of Drosophila. Nature. 1987;329:549–551. doi: 10.1038/329549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner ME, Hwang P, Huisman F, Taborek P, Yu CC, Mitchell BJ. Actin and microtubules drive differential aspects of planar cell polarity in multiciliated cells. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:19–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerdeman MW. Entwicklungsmechanische Untersuchungen uber die wimperbewegung des ectoderms von amphibienlarven. Rouxs Arch Dev Biol. 1925;106:41–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02079527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Ng CP, Habacher H, Roy S. Foxj1 transcription factors are master regulators of the motile ciliogenic program. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1445–1453. doi: 10.1038/ng.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H, Hoover AN, Liu A. PCP effector gene Inturned is an important regulator of cilia formation and embryonic development in mammals. Dev Biol. 2010;339:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]