Abstract

Highly compacted DNA nanoparticles (DNPs) composed of polyethylene glycol linked to a 30-mer of poly-L-lysine via a single cysteine residue (CK30PEG) have previously been shown to provide efficient gene delivery to the brain, eyes and lungs. In this study, we used a combination of flow cytometry, high-resolution live-cell confocal microscopy, and multiple particle tracking (MPT) to investigate the intracellular trafficking of highly compacted CK30PEG DNPs made using two different molecular weights of PEG, CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k. We found that PEG MW did not have a major effect on particle morphology nor nanoparticle intracellular transport. CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs both entered human bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells via a caveolae-mediated pathway, bypassing degradative endolysosomal trafficking. Both nanoparticle formulations were found to rapidly accumulate in the perinuclear region of cells within 2 h, 37 ± 19 % and 47 ± 8 % for CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k, respectively. CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs moved within live cells at average velocities of 0.09 ± 0.04 µm/s and 0.11 ± 0.04 µm/s, respectively, in good agreement with reported values for caveolae. These findings show that highly compacted DNPs employ highly regulated trafficking mechanisms similar to biological pathogens to target specific intracellular compartments.

Keywords: gene therapy, nonviral, intracellular trafficking, particle tracking, Cystic Fibrosis

1. Introduction

Most nonviral gene delivery systems enter cells by clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) [1–4]. Once internalized via CME, gene carriers typically undergo endolysosomal trafficking, where the cargo DNA is subject to degradation in the acidic and enzyme-rich environments of late endosomes and lysosomes [5]. In contrast, some viruses and bacterial pathogens employ internalization pathways that allow them to avoid endolysosomal degradation [6–8]. Recently, caveolae-mediated endocytosis has gained increasing attention as a portal of entry for a number of viruses and bacterial pathogens [9]. For example, SV40 has been found to utilize caveolae, cholesterol-rich membrane invaginations, for trafficking to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) outside of the endolysosomal pathway [10–11]. Synthetic systems capable of exploiting alternative intracellular pathways have been increasingly investigated, and may enhance the effectiveness of nonviral gene therapy [12–14].

Highly compacted DNA nanoparticles (DNPs), composed of 30-mer lysine conjugated to 10kDa polyethylene glycol (PEG) via a single cysteine moiety (CK30PEG10k), have shown remarkable effectiveness in delivering genes to the brain, eyes and lungs [15–17]. A unique feature of CK30PEG10k is that single DNA plasmids are compacted into rods with minor diameter <15 nm and with near neutral surface charge. They exhibit minimal toxicity and immunogenicity, and transfect non-dividing cells both in vitro and in vivo [17–19]. DNPs are the only polymeric system currently being tested clinically in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. In a Phase I/IIa clinical trial, CK30PEG10k DNPs administered to the nares of CF patients were well tolerated, non-toxic and showed partial to complete cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) chloride ion channel reconstitution. Although CK30PEG10k has emerged as a promising nonviral gene carrier, the current formulation may benefit from additional modifications aimed at overcoming various extracellular and intracellular barriers. A significant concern associated with CK30PEG10k for CF gene therapy is its high MW PEG, since 10kDa PEG coatings have been shown to be mucoadhesive, including on nanoparticles [20–24]. To reach the airway epithelium, gene carriers must rapidly penetrate the hyper-viscoelastic CF sputum. We have shown that polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles densely coated with PEG rapidly penetrate human cervicovaginal mucus and CF sputum as long as the PEG MW was 2–5 kDa, whereas they became trapped if PEG MW was 10kDa [21, 25]. Therefore, DNPs formulated with PEG with MW 2–5kDa may provide advantages for CF gene therapy.

In this study, we sought to investigate the intracellular trafficking of CK30PEG10k DNPs in live human airway epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells. In addition, based on our finding that the PEG MW may markedly influence the interactions of nanoparticles with secreted mucus constituents in the airways, we sought to determine if the use of 5kDa PEG coating (vs. 10kDa PEG used currently) may influence the cellular entry and trafficking process of highly compacted DNPs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Thiol reactive PEG, methoxy-PEG-maleimide, MW 10 and 5 kDa, was purchased from Rapp Polymere (Tübingen, Germany). Lab-Tek glass-bottom tissue culture plates were obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific (Rochester, NY). N-(3-triethylammoniumpropyl)-4-(6-(4-(diethylamino)phenyl)hexatrienyl)pyridinium dibromide (FM4-64), AlexaFluor555-labeled Cholera Toxin subunit B (CTB), tetramethylrhodamine-labeled Transferrin (TR-Transferrin), AlexaFluor488 and AlexaFluor555 SDP esters, Hoechst 34580, LysoTracker Red, ER-Tracker Red (BODIPY TR glibenclamide), 100nm carboxyl-modified fluorescent polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles, and Organelle Lights Endosome-RFP kit were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Vivaspin concentrators (100,000 MW cutoff) were from Sartorius (Bohemia, NY). Chlorpromazine, genistein, amiloride, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MBCD), lovastatin, 25kDa FITC-dextran, and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Formulation of highly compacted DNA nanoparticles (DNPs)

2.2.1. Synthesis of CK30PEG polymers

30-mer lysine with a terminal cysteine group, CK30, was synthesized using an automated solid phase peptide synthesizer (Symphony Quartet, Protein Technologies, Tucson, AZ). CK30 was purified by HPLC (C18 Reverse Phase Column) and identity confirmed by mass spectroscopy. Trifluoroacetate (TFA) was the counterion of the polycation. A block co-polymer of poly-L-lysine and polyethylene glycol, CK30PEG, was prepared as previously described [17], with two exceptions: (1) the MWs of PEG used were 10kDa and 5kDa, and (2) TFA counterion was replaced with acetate by size-exclusion chromatography on Sephadex G-25. Eluted fractions were monitored at 220 nm and samples were collected and then lyophilized.

2.2.2. Labeling of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k

CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k polymers were fluorescently-labeled with AlexaFlour488 or AlexaFluor555. CK30PEG (20 mg/ml in water) and AlexaFluor SDP ester dissolved in DMSO were added to 50mM carbonate buffer pH 9.5 and allowed to react for 4 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then purified using Sephadex G25 column equilibrated with 50 mM ammonium acetate (AA) to remove the unreacted dyes, and exchange the counterion from TFA to AA, and then lyophilized.

2.2.3 Assembly and characterization of DNA nanoparticles (DNPs)

The plasmid, pCMV-Luc, a gift from Dr. Alexander Klibanov (Department of Chemistry, MIT), was propagated as described [26]. DNPs were assembled by compacting plasmid DNA with CK30PEG10k or CK30PEG5k according to the protocol of Liu et al [17]. Briefly, 0.9 ml of DNA solution (0.222 mg/ml) was added dropwise into a swirling solution of 0.1 ml of CK30PEG10k or CK30PEG5k (6.4 or 4.3 mg/ml, respectively) in water. DNA nanoparticle complexes were allowed to form at room temperature for 30 min. Final DNA concentration was 0.2 mg/ml with an N to P ratio (N/P) of 2. Assembled DNPs were purified using vivaspin concentrators (100,000 MW cutoff) to remove free polymer and concentrate in 150 mM NaCl. Hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the assembled DNPs were evaluated using Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, U.K.). TEM images of the assembled DNPs were obtained using an Hitachi H7600 Transmission Electron Microscope.

2.3. Cell culture

BEAS-2B cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). In some cases, BEAS-2B cells were pre-transfected with Organelle Lights Endosome-RFP kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol, which contains a gene sequence that encodes for Rab5a-RFP (early endosome marker). For live-cell microscopy, cells were seeded between 2.0 – 2.5x103 cells per plate onto Lab-Tek glass-bottom culture plates and incubated overnight. After incubation, medium was replaced with fresh media before particles were added.

2.4. Confocal microscopy

LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) was used to capture images and time-lapse movies. For multi-color microscopy, samples were excited with 405, 488, 543 and 633nm laser lines, and images were captured by multi-tracking to avoid bleed-through between fluorophores. All samples were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 and observed under a 63X Plan-Apo/1.4 NA oil-immersion lens.

2.4.1 Cellular uptake and distribution in cytoplasm

Prior to imaging, BEAS-2B cells were treated for 10 min with Hoechst 33258 (5µg/ml) to stain the nucleus. After staining, cells were washed with 1X PBS and replaced with Opti-MEM (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) for imaging using confocal microscope. To evaluate the intracellular spatial distribution of gene carriers, the cytoplasm of each cell was divided into four radially equal quadrants (Q1 through Q4), where Q1 is closest to the nucleus and Q4 the furthest. DNA nanoparticle distributions in each quadrant were then quantified using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Corp., Downingtown, PA) on a per-pixel basis.

2.4.2 Co-localization with endocytic markers

In order to identify the endocytic pathway involved for CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs, co-localization with endocytic markers were studied in live BEAS-2B cells. In select experiments, cells were stained with TR-Transferrin (10 µg/ml) for 1 h, AlexaFluor555-CTB (3 µg/ml) for 30 min, or FITC-Dextran (1 mg/ml) for 30 min. In another experiment, cells were treated with LysoTracker (100nM) or ER-Tracker (1µM) for 30 min. After staining, cells were washed with 1X PBS and replaced with Opti-MEM for confocal imaging. For FM4-64 staining, cells were first washed and stained with FM4-64 for 10 min in Opti-MEM. Subsequently, nanoparticles were added and then imaged under confocal microscope. Image acquisition was limited to 200 ms per frame or less to maintain accurate co-localization information and then analyzed with MetaMorph software.

2.5. Drug inhibition of uptake pathways

BEAS-2B cells (3.0 × 105 cells/well in 6 well plates) were treated with either chlorpromazine (10 µg/ml), genistein (200 µM), amiloride (10 µM), or methyl-β-cyclodextrin (10 mM) with lovastatin (1 µg/ml) in media for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, labeled DNPs were added and incubated for another 2 h, after which cells were washed with 1X PBS and extracellular fluorescence was quenched with 0.4% (w/v) trypan blue. 4°C samples were pre-chilled for 30 min prior to addition of gene carriers and maintained at 4°C during the incubation period. Cells were then washed with 1X PBS and harvested with 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA and resuspended in 1X PBS. Mean fluorescence intensity was analyzed using FACSCaliber flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lake, NJ). Data from 10,000 events were gated using forward and side scatter parameters to exclude cell debris.

2.6. Live-cell real-time particle tracking

Intracellular motion of DNPs in live BEAS-2B cells was tracked in real-time using multiple particle tracking (MPT) of nanoparticles with the confocal microscope. MPT allows simultaneous multi-color tracking of particles within the same cell, eliminating potential cell to cell variation [27]. Light-intensity-weighted nanoparticle centroids of diffraction-limited images were tracked using MetaMorph software, thereby achieving resolution much higher than a pixel [28]. Intracellular transport of DNPs was recorded in 20 s movies at 200 ms resolution. The x, y coordinates were transformed into time-averaged mean-squared displacements (MSD), <Δr2(τ)> = [x(t+τ) − x(t)]2 + [y(t+τ) − y(t)]2 (τ=time scale), from which distributions of nanoparticle MSDs, time-dependent particle diffusion coefficients (Deff), and velocities were calculated. Bulk transport properties were obtained by geometric-averaging of individual ensemble transport rates. The mechanism of gene carrier transport over short and long time scales was classified based on the concept of relative change (RC) of effective diffusivity (Deff), as reported previously [27]. An RC standard curve, which plots the 95% distribution range of Deff for purely Brownian particles over time scale, was generated based on Monte Carlo simulations [27, 29]. RC value between the upper and lower bounds is classified as diffusive, below the lower bound is immobile & hindered diffusion, and above the upper bound is active.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey HSD test (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) or one-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at a level of P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Cellular entry of DNA nanoparticles (DNPs)

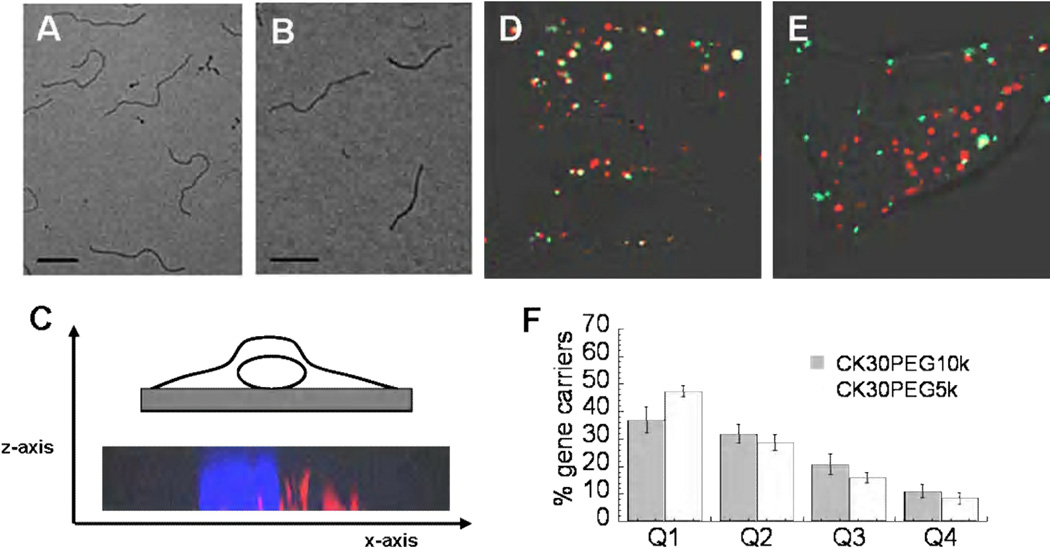

DNPs compacted with CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k showed similar rod-like morphologies by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), with average dimensions (length×width) of 350×11 nm and 300×13 nm, respectively (Fig. 1a,b). Both formulations had near neutral surface charge, as measured by ζ-potential (−1.5 ± 3.6 mV and −1.4 ± 0.6 mV, respectively), and were colloidally stable in saline for at least two months at 4°C (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1.

TEM images of (A) CK30PEG10k and (B) CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles complexed with plasmid DNA. Scale bar denotes 200nm. Confocal microscopy images of BEAS-2B cells showing (C) 3-D projection of series of images from z-stack scan, confirming that particles (red) are inside the cell. The nucleus is stained with Hoechst 34580 (blue). (D) Co-localization image between CK30PEG10k (green) and CK30PEG5k (red) DNA nanoparticles. (E) Co-localization image between 100nm PS nanoparticles (green) and CK30PEG5k (red) DNA nanoparticles. (F) Quantitative intracellular spatial distribution analysis of DNA nanoparticles after 2 hours (n=15 cells). The cytoplasmic space, with the nuclear envelope and plasma membrane as boundaries, was divided into 4 radially equal segments to yield four quadrants (Q1-Q4), where Q1 is closest to the nucleus and Q4 furthest.

Fluorescently-labeled CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs both entered human bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells within 2 h; nanoparticle internalization was confirmed by a z-stack scan (x–z projection) (Fig. 1c). Co-localization with Cy3 labeled DNA (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI) confirmed that DNPs remained intact in the cytoplasm (Supplementary Figure S1). To investigate if the two nanoparticles trafficked in the same intracellular pathway, we co-incubated BEAS-2B cells with labeled CK30PEG10k (green) and CK30PEG5k (red) nanoparticles. The two nanoparticle formulations exhibited substantial co-localization with each other, 67 ± 16% on a per pixel basis (Fig. 1d), suggesting that most of them undergo similar intracellular trafficking. Both nanoparticle formulations showed negligible co-localization with 100nm PS nanoparticles (Fig. 1e), which we and others have previously shown to undergo endolysosomal trafficking upon CME-mediated uptake [27, 30–31]. Both DNA nanoparticle formulations were found to rapidly accumulate in the perinuclear region of cells. On average, 37 ± 19 % and 47 ± 8 % of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k were found in the perinuclear region (Q1) within 2 h post-incubation, respectively. The other three regions (Q2 to Q4) each contained less than 30% of the total gene carriers (Fig. 1f).

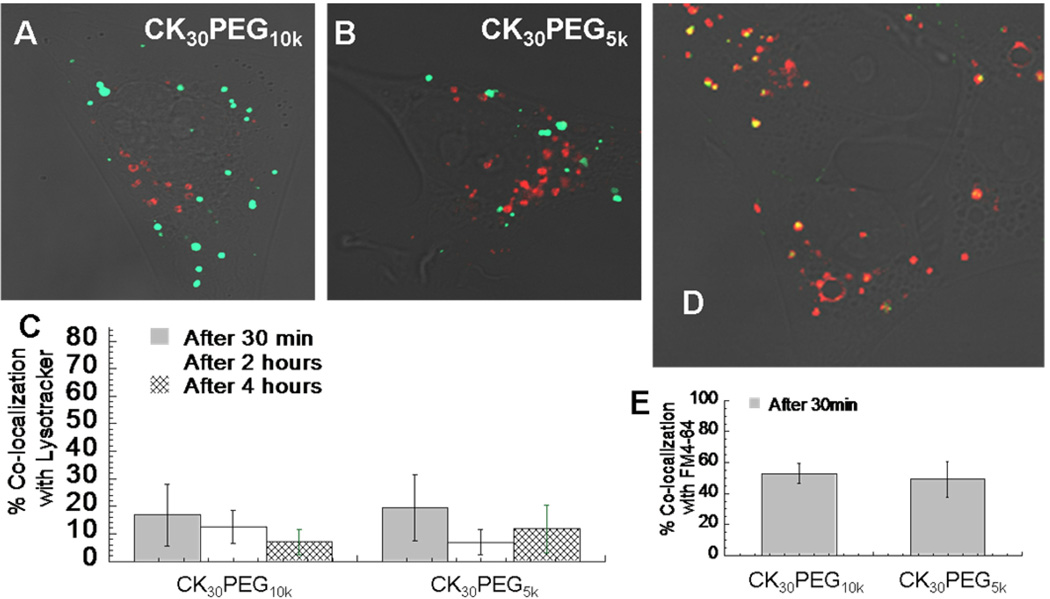

3.2 CK30PEG DNPs avoid endolysosomal trafficking

The predominant intracellular pathway for nonviral gene carriers following internalization is routing to early endosomes (EE), which mature into, or later merge with, acidic late endosomes and lysosomes [1, 5]. Our observation of negligible co-localization between CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs with 100nm PS nanoparticles (Fig. 1e) suggested that they may be routed outside of the endolysosomal pathway. Nevertheless, the low co-localization could also potentially reflect sequestration within different vesicles, or differences in the temporal processing within the endolysosomal pathway. To eliminate these possibilities, we performed co-localization studies in BEAS-2B cells using Rab5a-RFP, a well-characterized marker extensively used to identify EE. We found that CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs did not co-localize with Rab5a-RFP during the first 30 min, or anytime thereafter (Fig. 2a,b). We also performed co-localization studies using LysoTracker, an acid sensitive probe that labels late endosomes and lysosomes. We observed minimal co-localization between CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs with LysoTracker for up to 4 h post-incubation (Fig. 2c). In contrast, LysoTracker was highly co-localized with 100nm PS nanoparticles, confirming that 100nm PS nanoparticles are largely sequestered in acidic vesicles of endolysosomal pathway (data not shown). Altogether, these data strongly suggest that the trafficking of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs is independent of the degradative endolysosomal pathway. We also performed co-localization analysis with FM4-64, a lipophilic endocytic vesicle staining probe. Confocal microscope images show that both CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs are highly co-localized with FM4-64 in as little as 30 min (Fig. 2d,e), suggesting that both types of DNPs are trafficked within vesicular structures inside the cell.

Figure 2.

BEAS-2B cells pre-transfected with RFP-fused Rab5a protein (early endosome marker) show a negligible co-localization with (A) CK30PEG10k and (B) CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles. (C) Quantitative co-localization analysis between CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles with lysotracker at different time point. (D) Representative image of CK30PEG10k DNA nanoparticle (green) endocytosed in vesicles stained with FM4-64 (red). (E) Quantitative co-localization analysis between CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles with FM4-64.

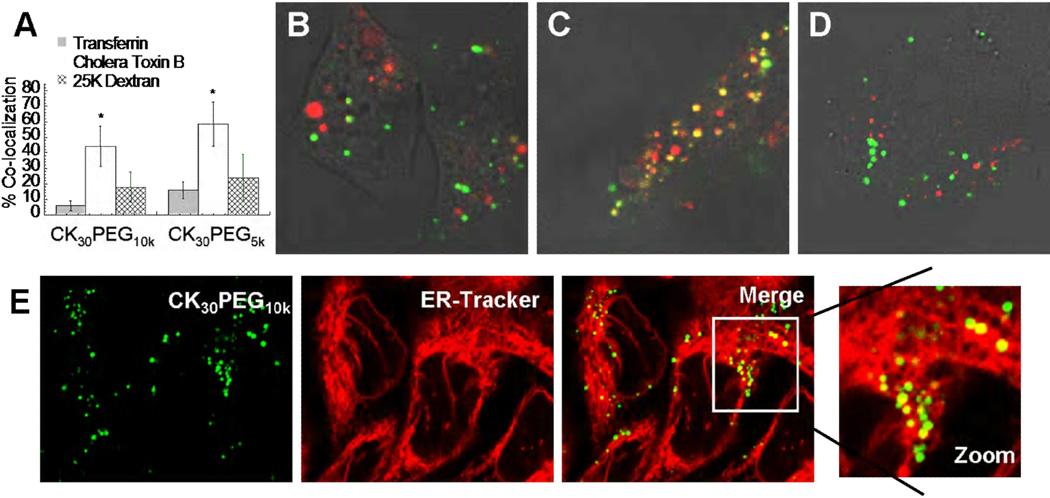

3.3 DNPs enter cells by caveolae-mediated endocytosis

The endocytic mechanism of nanoparticles can determine their intracellular trafficking [3, 19, 29–34]. Thus, we next sought to investigate the cellular entry mechanism for CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs using widely accepted and well characterized endocytic markers. DNPs were added to BEAS-2B cells incubated with TR-Transferrin, which labels vesicles that originate from clathrin-mediated endocytosis; AlexaFluor555-CTB, which labels vesicles from caveolae-mediated uptake; and FITC-dextran, which labels vesicles from macropinocytosis. We found that CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs were highly co-localized with CTB, but exhibited low co-localization with Transferrin and Dextran (Fig. 3a-d), suggesting they primarily enter the lung epithelial cells via caveolae. We also investigated trafficking of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs to the ER, a common cellular destination for viruses utilizing caveolae-mediated pathway [10–11]. A high degree of co-localization was observed between the gene carriers and ER-Tracker, suggesting localization to the ER (Figure 3e). However, due to the highly convoluted structure of the ER, it was not possible to conclude with confidence that they were within the ER luminal space or in the cytoplasmic space in between ER membranes.

Figure 3.

Endocytic pathway mechanism for CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles. (A) Quantitative co-localization analysis for DNA nanoparticles with Transferrin, Cholera Toxin subunit B (CTB), and 25kDa MW dextran. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated with asterisks (*). Representative co-localization images of CK30PEG10k DNA nanoparticle with (B) Transferrin, (C) CTB, and (D) 25kDa MW dextran. (E) Representative images showing CK30PEG10k DNA nanoparticles highly co-localized with ER-Tracker.

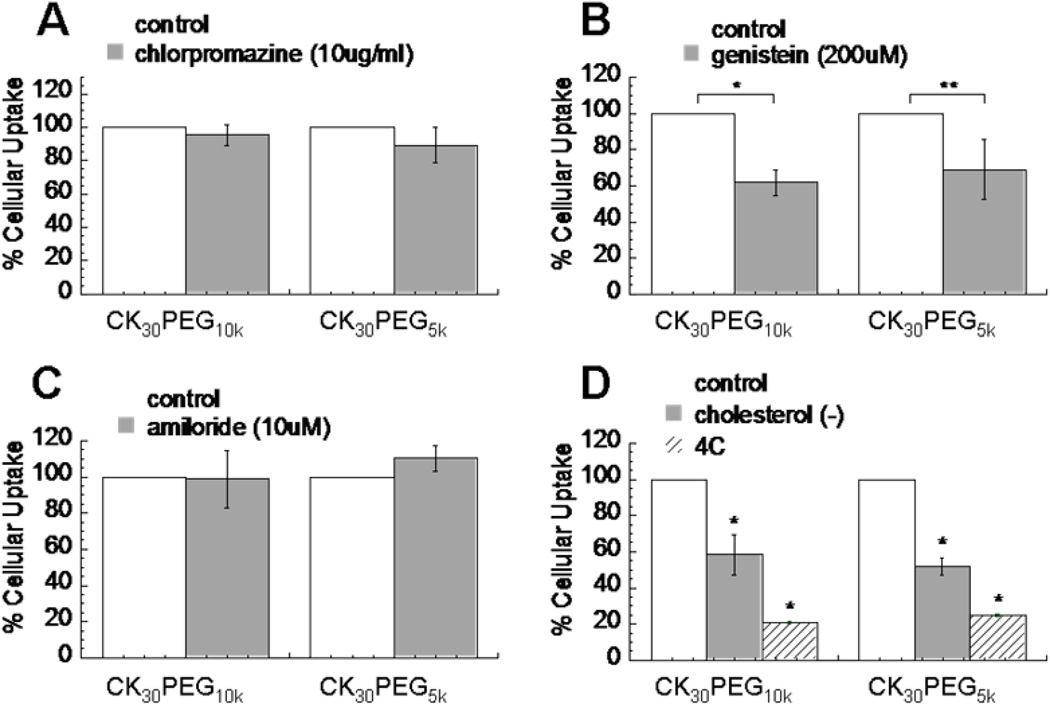

To confirm our observations, we also measured the uptake of DNPs in the presence of different endocytic inhibitors using flow cytometry. Compared to the untreated control cells, the uptake of both nanoparticle formulations were largely unaffected by cell treatment with chlorpromazine, which blocks CME by causing clathrin to accumulate in late endosomes (Fig. 4a). In contrast, cell treatment with genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks caveolae uptake, sharply reduced the internalization of both nanoparticle formulations (Fig. 4b). Cell treatment with amiloride, which inhibits macropinocytosis by blocking sodium-proton exchange, also did not reduce the uptake of either type of DNPs (Fig. 4c). Cellular uptake of the DNPs was also significantly inhibited when cells were incubated at 4°C, suggesting that nanoparticles enter cells via an energy-dependent endocytic mechanism and not via direct penetration of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4d). Finally, cellular uptake of the DNPs was significantly reduced by cholesterol depletion, using methyl-β-cyclodextrin (extracts cholesterol from plasma membrane) and lovastatin (inhibitor of de novo cholesterol synthesis), in good agreement with cholesterol-dependent nature of caveolae-mediated endocytosis (Fig. 4d). Taken together, these data suggest that both CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs primarily enter human airway epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells by caveolae-mediated endocytosis.

Figure 4.

Flow Cytometry analysis for drug inhibition of uptake pathways. (A) Clathrin-mediated endocytosis inhibiting agent, chloroprazamine, did not inhibit uptake of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles. (B) Caveolae-mediated endocytosys-inhibiting agent, genistein, significantly reduced uptake of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles. (C) Macropinocytosis-inhibiting agent, amiloride, did not inhibit uptake of either CK30PEG10k or CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles. (D) Cellular uptake of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles is greatly reduced with cholesterol depletion (extracted using methyl-β-cyclodextrin and lovastatin) and at 4°C. Statistically significant differences from no treatment control is indicated with asterisks (*) (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.1).

3.4 Particle tracking of individual gene carriers in live BEAS-2B cells

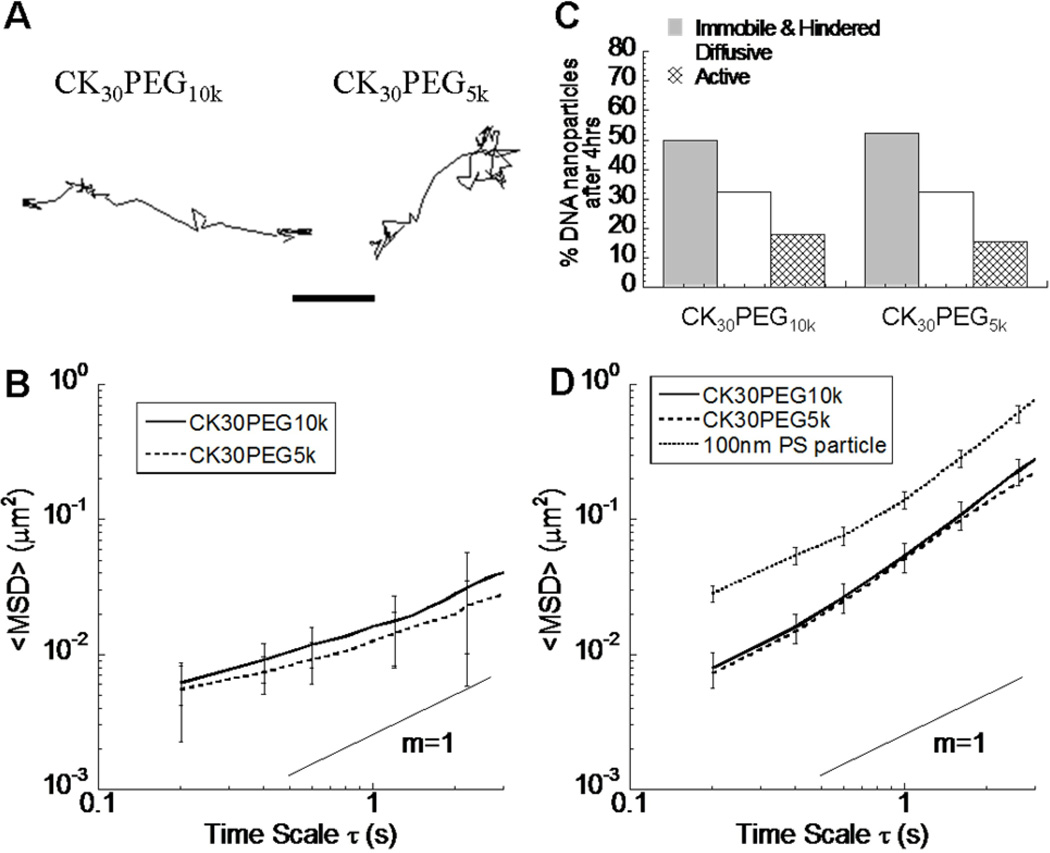

We and others have shown that various intracellular trafficking pathways exhibit distinct transport kinetics [27, 29, 35–37]. We thus measured the real-time intracellular motion of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs in live BEAS-2B cells using multiple particle tracking (MPT). To eliminate potential cell to cell variations, we recorded the dynamic motion of CK30PEG10k (green) and CK30PEG5k (red) DNPs in the same cells. The trajectories of DNPs undergoing active transport were similar, and included a substantial fraction of pearls-on-a-string motion with linear or curvilinear trajectories (Fig. 5a), in agreement with microtubule-dependent motor protein driven active transport [29]. The geometric ensemble-average mean-squared displacements (<MSD>) of both CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs were similar across all time scales at 4 h after incubation, with no statistical differences (Fig. 5b). Using a transport mode classification scheme based on time-scale dependent effective diffusion coefficient (Deff), we found 18% and 15% of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs were undergoing active transport, respectively (Fig. 5c). Similarly, the <MSD> for the fraction of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs undergoing active transport were identical across all time scales (Fig. 5d). The average velocities of actively transported CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs were 0.09 ± 0.04 µm/s and 0.11 ± 0.04 µm/s, respectively. In contrast, the <MSD> for actively transported 100nm PS nanoparticles were 3- to 8-fold higher than that of CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs, depending on the time scale (Fig. 5d). Distinct intracellular transport between the DNPs and 100nm PS nanoparticles further confirms that the DNPs were trafficked within a distinct pathway compared to PS nanoparticles.

Figure 5.

Intracellular transport of CK30PEG10k (n=143 particles) and CK30PEG5k (n=181 particles) DNA nanoparticles in live BEAS-2B cells (n=15 cells) at 4 h post incubation. (A) Representative 20 s trajectories of actively transported DNA nanoparticles display linear or curvilinear, directed long range motions. Scale bar represents 1 µm. (B) Ensemble geometric mean squared displacements (<MSD>) with respect to time scale for DNA nanoparticles. (C) Transport mode distributions for DNA nanoparticles. The transport modes are classified into immobile & hindered, diffusive, and active transport. (D) <MSD> with respect to time scale for actively transported CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNA nanoparticles compared to 100nm PS nanoparticles (n=80 particles). The difference in the <MSD> was statistically significantly across all time scales (p<0.05). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Error bars for CK30PEG5k have been omitted for clarity (Figure 5D).

4. Discussion

We used a combination of flow cytometry, high-resolution live-cell confocal microscopy, and MPT to investigate the intracellular trafficking of highly compacted CK30PEG10k DNA nanoparticles (DNPs) that have recently been successfully tested in Phase I/IIa clinical trials, and one variant with lower MW PEG, CK30PEG5k. Human bronchial epithelial cells, BEAS-2B, are amongst the most prominent models for the study of cell biology, pathologic processes, drug metabolism and gene delivery at the airway epithelium [38]. BEAS-2B cells grown under liquid-covered culture conditions can be imaged without fixation by high resolution microscopy to study the transport of individual nanoparticles in living cells. CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs both entered BEAS-2B cells by employing a caveolae-mediated pathway, leading to non-degradative trafficking. The trafficking of DNA and gene carriers in the acidic endolysosomal pathway has long been considered a critical bottleneck in nonviral gene therapy [1–2]. Therefore, by exploiting cavelae-mediated pathway, the DNPs avoid endolysosomal degradation, which may help explain high in vivo gene transfer efficiencies previously reported for highly compacted CK30PEG10k DNPs [17–19].

Our result is consistent with the previous report from Chen et al., which showed that rod-shaped CK30PEG10k DNPs do not enter the endolysosome pathway following uptake in HeLa and 16HEBo- cells [19]. Recently, the same authors showed that the cellular uptake of DNPs is lipid raft dependent, which is used by most endocytic pathways including caveolae-mediated endocytosis [39]. However, Walsh et al. previously found that CK30PEG5k enter COS-7 cells by macropinocytosis [40]. This difference may be attributed to the different cell types used, perhaps due to inherent differences in membrane compositions and constitutive cellular endocytosis regulation. Another possibility is that live-cell imaging was used in our study, compared to fixed-cell imaging in the study by Walsh and colleagues. The different endocytic mechanisms may also be a consequence of different geometric dimensions of the DNPs, despite using the same polymer system. By using trifluoroacetate as the counterion during formation, Walsh et al. formulated toroid/rod-shaped particles that likely have a minor diameter in excess of 40nm [40]. In contrast, using ammonium acetate as the counterion, we made purely rod-shaped particles with minor diameter below 20nm [17–19]. The finding that the size of DNPs may influence their intracellular trafficking is consistent with previous work that showed 43nm polymer nanoparticles entered HeLa cells by CME, whereas similar, but smaller, 24nm nanoparticles entered via a non-clathrin, non-caveolae mechanism that leads to non-degradative trafficking [31]. It was also reported that only quantum dots (QDs) having sizes <20 nm exploited caveolae-mediated endocytosis, whereas QDs larger than 20 nm did not use this pathway [41]. In another study, Sahay et al. reported caveolae-mediated cellular entry for a single chain of pluronic P85, similar to the DNPs studied in this work [34].

Caveolae are cholesterol-rich flask-shaped invaginations with 50–100 nm diameters [42]. Although the dynamic process that enables nanoparticles to access caveolae invaginations and enter cells remains unknown [30, 32, 43], rapid perinuclear accumulation of the DNPs (within 2 h) suggests that their intracellular trafficking involves transport by motor proteins. Noda and co-workers have reported that minus end-directed kinesin, KIFC3, motors move detergent resistant membranes, such as caveolae, along microtubules with an average velocity of 0.075 µm/s [44], which is very close to the velocities found for CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs reported here. In another study, caveolin-1-GFP labeled vesicles were reported to move at speeds ranging from 0.3 to 2.0 µm/s [45], however the analysis did not include immobile caveolin-1-GFP vesicles. Therefore, the average velocity including immobile caveolae would likely be closer to that reported here. We found that the actively transported CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs moved 3- to 8-fold slower in BEAS-2B cells when compared to 100nm PS nanoparticles that entered via CME. Interestingly, the mobility of the DNPs observed here is similar to that found for nanoparticles accessing a non-degradative trafficking pathway via non-clathrin, non-caveolae mediated endocytic mechanism [27]. Due to their perinuclear trafficking, slower DNA nanoparticle mobility may lead to extended residence time near the nucleus, which may enhance the delivery of DNA to the nucleus [28, 46–47]. Finally, CK30PEG10k and CK30PEG5k DNPs showed a high degree of co-localization with ER-Tracker, suggesting that these gene carriers are trafficked to the ER on their way to delivering their DNA payload to the cell nucleus.

Advantages of PEG coating on nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery have been widely reported in the literature [48–49]. PEG coatings offer resistance to degradation by nucleases, provide increased colloidal stability, and confer stealth like properties to evade the reticuloendothelial system for long circulation in the bloodstream [50]. Furthermore, low MW PEG coatings may be required to reduce mucoadhesion [21], presumably by avoiding interpenetrating polymer network and/or hydrogen bonding between PEG chains and the mucus mesh. Our results show that varying the PEG MW, from 10kDa to 5kDa, does not significantly affect particle morphology nor intracellular trafficking of a promising polymer-based gene delivery system. These findings encourage further work to develop low MW PEG coating CK30PEG DNPs for mucosal gene therapy applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01EB003558 and P01HL51811) and Wilmer Microscopy Core Facility Grant (EY001765). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jensen KD, Nori A, Tijerina M, Kopeckova P, Kopecek J. Cytoplasmic delivery and nuclear targeting of synthetic macromolecules. J Control Release. 2003;87:89–105. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng W, Parker TL, Kallinteri P, Walker DA, Higgins S, Hutcheon GA, Garnett MC. Uptake and metabolism of novel biodegradable poly (glycerol-adipate) nanoparticles in DAOY monolayer. J Control Release. 2006;116:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Won YY, Sharma R, Konieczny SF. Missing pieces in understanding the intracellular trafficking of polycation/DNA complexes. J Control Release. 2009;139:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalil IA, Kogure K, Akita H, Harashima H. Uptake pathways and subsequent intracellular trafficking in nonviral gene delivery. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:32–45. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wattiaux R, Laurent N, Wattiaux-De Coninck S, Jadot M. Endosomes, lysosomes: their implication in gene transfer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000;41:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR. Dissecting virus entry via endocytosis. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1535–1545. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR. Influenza virus can enter and infect cells in the absence of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Virol. 2002;76:10455–10464. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10455-10464.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith AE, Helenius A. How viruses enter animal cells. Science. 2004;304:237–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1094823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medina-Kauwe LK. "Alternative" endocytic mechanisms exploited by pathogens: new avenues for therapeutic delivery? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelkmans L, Kartenbeck J, Helenius A. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 reveals a new two-step vesicular-transport pathway to the ER. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:473–483. doi: 10.1038/35074539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelkmans L, Puntener D, Helenius A. Local actin polymerization and dynamin recruitment in SV40-induced internalization of caveolae. Science. 2002;296:535–539. doi: 10.1126/science.1069784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medina-Kauwe LK. "Alternative" endocytic mechanisms exploited by pathogens: New avenues for therapeutic delivery? Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2007;59:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLendon PM, Fichter KM, Reineke TM. Poly(glycoamidoamine) vehicles promote pDNA uptake through multiple routes and efficient gene expression via caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:738–750. doi: 10.1021/mp900282e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabrielson NP, Pack DW. Efficient polyethylenimine-mediated gene delivery proceeds via a caveolar pathway in HeLa cells. J Control Release. 2009;136:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yurek DM, Fletcher AM, Smith GM, Seroogy KB, Ziady AG, Molter J, Kowalczyk TH, Padegimas L, Cooper MJ. Long-term transgene expression in the central nervous system using DNA nanoparticles. Mol Ther. 2009;17:641–650. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding XQ, Quiambao AB, Fitzgerald JB, Cooper MJ, Conley SM, Naash MI. Ocular delivery of compacted DNA-nanoparticles does not elicit toxicity in the mouse retina. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu G, Li D, Pasumarthy MK, Kowalczyk TH, Gedeon CR, Hyatt SL, Payne JM, Miller TJ, Brunovskis P, Fink TL, Muhammad O, Moen RC, Hanson RW, Cooper MJ. Nanoparticles of compacted DNA transfect postmitotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32578–32586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziady AG, Gedeon CR, Miller T, Quan W, Payne JM, Hyatt SL, Fink TL, Muhammad O, Oette S, Kowalczyk T, Pasumarthy MK, Moen RC, Cooper MJ, Davis PB. Transfection of airway epithelium by stable PEGylated poly-L-lysine DNA nanoparticles in vivo. Mol Ther. 2003;8:936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Kube DM, Cooper MJ, Davis PB. Cell surface nucleolin serves as receptor for DNA nanoparticles composed of pegylated polylysine and DNA. Mol Ther. 2008;16:333–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai SK, O'Hanlon DE, Harrold S, Man ST, Wang YY, Cone R, Hanes J. Rapid transport of large polymeric nanoparticles in fresh undiluted human mucus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1482–1487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608611104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang YY, Lai SK, Suk JS, Pace A, Cone R, Hanes J. Addressing the PEG mucoadhesivity paradox to engineer nanoparticles that "slip" through the human mucus barrier. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:9726–9729. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suk JS, Lai SK, Wang YY, Ensign LM, Zeitlin PL, Boyle MP, Hanes J. The penetration of fresh undiluted sputum expectorated by cystic fibrosis patients by non-adhesive polymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2591–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai SK, Wang YY, Hanes J. Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:158–171. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai SK, Wang YY, Hida K, Cone R, Hanes J. Nanoparticles reveal that human cervicovaginal mucus is riddled with pores larger than viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:598–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911748107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suk JS, Lai SK, Wang YY, Ensign LM, Zeitlin PL, Boyle MP, Hanes J. The penetration of fresh undiluted sputum expectorated by cystic fibrosis patients by non-adhesive polymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2591–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning : a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai SK, Hida K, Chen C, Hanes J. Characterization of the intracellular dynamics of a non-degradative pathway accessed by polymer nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2008;125:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suh J, Dawson M, Hanes J. Real-time multiple-particle tracking: applications to drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suh J, Wirtz D, Hanes J. Efficient active transport of gene nanocarriers to the cell nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3878–3882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0636277100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rejman J, Oberle V, Zuhorn IS, Hoekstra D. Size-dependent internalization of particles via the pathways of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Biochem J. 2004;377:159–169. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai SK, Hida K, Man ST, Chen C, Machamer C, Schroer TA, Hanes J. Privileged delivery of polymer nanoparticles to the perinuclear region of live cells via a non-clathrin, non-degradative pathway. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2876–2884. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahay G, Alakhova DY, Kabanov AV. Endocytosis of nanomedicines. J Control Release. 2010;145:182–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahay G, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Different internalization pathways of polymeric micelles and unimers and their effects on vesicular transport. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:2023–2029. doi: 10.1021/bc8002315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahay G, Gautam V, Luxenhofer R, Kabanov AV. The utilization of pathogen-like cellular trafficking by single chain block copolymer. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1757–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bausinger R, von Gersdorff K, Braeckmans K, Ogris M, Wagner E, Brauchle C, Zumbusch A. The transport of nanosized gene carriers unraveled by live-cell imaging. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:1568–1572. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braeckmans K, Buyens K, Naeye B, Vercauteren D, Deschout H, Raemdonck K, Remaut K, Sanders NN, Demeester J, De Smedt SC. Advanced fluorescence microscopy methods illuminate the transfection pathway of nucleic acid nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2010;148:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai SK, Hanes J. Real-time multiple particle tracking of gene nanocarriers in complex biological environments. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;434:81–97. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-248-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steimer A, Haltner E, Lehr CM. Cell culture models of the respiratory tract relevant to pulmonary drug delivery. J Aerosol Med. 2005;18:137–182. doi: 10.1089/jam.2005.18.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen X, Shank S, Davis PB, Ziady AG. Nucleolin-mediated cellular trafficking of DNA nanoparticle is lipid raft and microtubule dependent and can be modulated by glucocorticoid. Mol Ther. 2011;19:93–102. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walsh M, Tangney M, O'Neill MJ, Larkin JO, Soden DM, McKenna SL, Darcy R, O'Sullivan GC, O'Driscoll CM. Evaluation of cellular uptake and gene transfer efficiency of pegylated poly-L-lysine compacted DNA: implications for cancer gene therapy. Mol Pharm. 2006;3:644–653. doi: 10.1021/mp0600034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahay G, Alakhova DY, Kabanov AV. Endocytosis of nanomedicines. J Control Release. 2010;145:182–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gumbleton M, Abulrob AG, Campbell L. Caveolae: an alternative membrane transport compartment. Pharm Res. 2000;17:1035–1048. doi: 10.1023/a:1026464526074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rejman J, Conese M, Hoekstra D. Gene transfer by means of lipo- and polyplexes: role of clathrin and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. J Liposome Res. 2006;16:237–247. doi: 10.1080/08982100600848819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noda Y, Okada Y, Saito N, Setou M, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Hirokawa N. KIFC3, a microtubule minus end-directed motor for the apical transport of annexin XIIIb-associated Triton-insoluble membranes. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:77–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mundy DI, Machleidt T, Ying YS, Anderson RG, Bloom GS. Dual control of caveolar membrane traffic by microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4327–4339. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luby-Phelps K. Cytoarchitecture and physical properties of cytoplasm: volume, viscosity, diffusion, intracellular surface area. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;192:189–221. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lukacs GL, Haggie P, Seksek O, Lechardeur D, Freedman N, Verkman AS. Size-dependent DNA mobility in cytoplasm and nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1625–1629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeRouchey J, Walker GF, Wagner E, Radler JO. Decorated rods: A "bottom-up" self-assembly of monomolecular DNA complexes. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2006;110:4548–4554. doi: 10.1021/jp053760a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li SD, Huang L. Nanoparticles evading the reticuloendothelial system: Role of the supported bilayer. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Biomembranes. 2009;1788:2259–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogris M, Brunner S, Schuller S, Kircheis R, Wagner E. PEGylated DNA/transferrin-PEI complexes: reduced interaction with blood components, extended circulation in blood and potential for systemic gene delivery. Gene Ther. 1999;6:595–605. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.