Abstract

Mitochondria play a critical role in cell survival and death. Mitochondrial recovery during inflammatory processes such as sepsis is associated with cell survival. Recovery of cellular respiration, mitochondrial biogenesis and function requires coordinated expression of transcription factors encoded by nuclear and mitochondrial genes, including mitochondrial transcription factor A (T-fam) and cytochrome c oxidase (COX, complex IV). LPS elicits strong host defenses in mammals with pronounced inflammatory responses but also triggers activation of survival pathways such as AKT pathway. AKT/PKB is a serine/threonine protein kinase playing an important role in cell survival, protein synthesis, and controlled inflammation in response to TLRs. Hence, we investigated the role of LPS mediated AKT activation in mitochondrial bioenergetics and function in cultured murine macrophages (B6-MCL) and bone marrow derived macrophages. We show that LPS challenge led to increased expression of T-fam and COX subunit I and IV in a time dependent manner through early phosphorylation of the PI3kinase/AKT pathway. PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitors abrogated LPS mediated T-fam and COX induction. Lack of induction was associated with decreased ATP production, increased proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α), nitric oxide production and cell death. The TLR4 mediated AKT activation and mitochondrial biogenesis required activation of adaptor protein MyD88 and Toll-IL-1R-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF). Importantly, using a genetic approach, we show that the AKT1 isoform is pivotal in regulating mitochondrial biogenesis in response to TLR4 agonist.

Introduction

Mammalian immune cells evolved to recognize pathogens through pattern recognition receptors, such as TLRs that recognize a wide range of microbial pathogens. Recognition of microbial components by TLRs triggers a cascade of cellular signaling leading to inflammatory gene expression and clearance of invading organisms. LPS, a major bacteria-derived cell wall component recognized by TLR4, elicits strong host defenses in mammals with pronounced inflammatory responses (1). Such responses are characterized by activation of inflammatory cascades with release of soluble cytokines and chemokines such as TNF-α, interleukin 6 and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide that subsequently facilitate the eradication of pathogens. While inflammation is necessary to eradicate pathogens, excessive inflammation may lead to host tissue injury and cell death. This might be, at least in part, due to the effect of inflammation on mitochondrial bioenergetics and mitochondrial injury.

Mitochondria provide the majority of cellular energy in form of ATP and are the major source of ROS(2). Cellular immune response to pathogens require high energy in the form of ATP and it appears that TLR mediated mitochondrial ROS are important for macrophage bactericidal activity (3). However, excessive reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generation during inflammation may damage mitochondria causing bioenergetic failure. This process is thought to be due to inhibition of the electron transfer chain (ETC) (4) through secondary modification of enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) and uncoupling of electron transport from ATP synthesis. Using an inflammation model, we have shown that TNF-α inhibits the activity of cytochrome c oxidase (COX) in bovine liver and in murine hepatocytes (5). This inhibition was associated with decreased ATP production and defective electron transport to molecular oxygen. Several reports suggest regeneration of mitochondria, upregulation of ETC capacity, and generation of new mitochondria later in the disease process after acute insults such as hypoxemia or sepsis is important for survival (6–8). The exact mechanism underlying the recovery of bioenergetic failure after inflammatory insult is not well studied.

LPS stimulation under specific conditions leads to activation of the pro-survival cascade followed by growth and differentiation. For example, it has been shown that LPS may serve as a signal to promote preconditioning and to protect against reperfusion injury (9). This bifunctionality of LPS is neither well understood nor studied. Among numerous pathways activated through TLR-mediated signaling, the PI3K/AKT pathway plays a central role in the regulation of cell survival and proliferation (9, 10). Evidence suggests an important negative regulatory role for the PI3K/AKT pathway in innate immune responses to TLR agonists (11). While growth factor mediated PI3K activation and the subsequent AKT activation is well characterized, TLR-mediated AKT activation and its role in inflammation and mitochondrial recovery in response to TLR4 agonists is not well defined. It was shown that certain TLRs, such as TLR4 requires the adaptor protein myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) and TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) to interact and activate PI3K/AKT pathway (12, 13). The PI3K/AKT pathway plays both pro- and anti- inflammatory roles in TLR signaling (11, 14). The PI3K/AKT pathway may be a link between immune response through TLRs and restoring energy metabolism through mitochondrial biogenesis.

Recovery of energy capacity by biogenesis requires coordinated expression of genes encoded by two independent genomes (nuclear and mitochondrial), including transcription factor activation and their binding to promoter consensus sequences in nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins (7, 15). Among the transcriptional regulators the mitochondria transcription factor (T-fam) A, a nuclear-encoded protein, governs mitochondrial gene expression (16, 17). In addition, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1-alpha (PGC-1α) and nuclear respiratory factors (NRF-1 and 2) are involved in nuclear respiratory gene expression and serve to integrate mitochondrial gene expression with a wide range of cellular functions (17, 18).

The exact molecular mechanism of LPS-mediated bioenergetic recovery is not known. Here, using a murine macrophage cell line and macrophages lacking MyD88/TRIF, we investigated the effect of LPS on mitochondrial bioenergetics. We show that recovery of cellular energy perturbation after LPS treatment is closely related to PI3K/AKT activation, and inhibition of this pathway is directly related to bioenergetic failure and cell death. Using a genetic approach we show that the AKT1 isoform plays a critical role in mitochondrial bioenergetics in response to TLR4. We present data that indicate that TLR4 mediated AKT activation requires adaptor protein MyD88 and TRIF. Such activation is critical for T-fam upregulation, and increased expression and activity of both COX subunit I (mitochondrially encoded) and COX subunit IV (nuclear encoded).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) unless specified otherwise. Inhibitors (LY294002, wortmannin, okadaic acid) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, California). Ultra pure LPS was purchased from InVivoGen (San Diego, California). Anti-phospho AKT and PI3 kinase, total AKT, AKT1, AKT2 and β actin antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, CA). Antibodies againstPI3 kinase and T-fam were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against mitochondrial complexes, cytochrome c oxidase subunit I and IV (COX I and COX IV) were purchased from Mitosciences (Eugene, Oregon). Anti-body against MnSOD was purchased from New England Biolab (Ipswich, MA). Anti-mouse IgG and anti-Rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-linked (HRP) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, CA), and anti-goat HRP was purchased from Bio-RAD (Hercules, CA).

Cell culture

The mouse macrophage cell line (B6-MCL) and MyD88/TRIF−/− cell line were generous gifts of Dr. Eicke Latz (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA). Both cell lines were generated from wild-type C57BL6 mice as previously described (19) and MyD88/TRIF−/− macrophages were generated from the same background mice as previously described (20). B6-MCL and cells deficient in MyD88/TRIF were grown in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), antibiotics, sodium pyruvate, nonessential amino acids and beta-mercaptoethanol.

RAW 264.7 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in a 95% air, 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C in RPMI medium supplemented with L-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin and 10% FCS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Mice and Macrophages

MYD88−/− and TRIF−/− mice were generated as previously described(21). AKT1−/− and AKT2−/− mice were generated as previously described (22, 23). All mice were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background at least ten times. Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were maintained at animal facilities at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI) and University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA). Animal studies were approved by the University of Michigan and University of Pennsylvania Committee on Use and Care of Animals.

Isolation of Bone Marrow Derived Macrophages (BMDMs)

BMDMs from AKT1−/−, AKT2−/− mice, MyD88−/− and TRIF−/− mice were prepared as described (24). Briefly, femurs and tibias from 6- to 12-week-old mice were dissected, and the bone marrow was flushed out. Bone marrow cells were cultured with IMDM media supplemented with 30% L929 supernatant containing macrophage-stimulating factor, glutamine, sodium pyruvate, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (GIBCO-BRL), and antibiotics for 5–7 days. Macrophages were re-plated at a density of 2 × 106 cells/well the day before the experiment.

Protein Extraction and Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested after the appropriate treatment and washed with PBS. Total cellular proteins were extracted after addition of a protease inhibitor cocktail and antiphosphatase I and II, by adding RIPA buffer (Sigma Aldrich). Protein concentrations of samples were measured with the BCA assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of protein (5–30 µg) were mixed with same volume of sample buffer (20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 1.25 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8), loaded on to a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and run at 40 mA for 3 h. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for 30 min at 20 V using a SemiDry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad). The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% dry milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h, washed, and incubated with primary antibody (diluted between 1/500 and 1/1000 in 5% dry milk in TBST) overnight at 4° C. The blots were washed four times with TBST and then incubated for 1 h with HRP-conjugated secondary anti-IgG Ab using a dilution between 1/5,000 and 1/10,000 in 5% dry milk in TBST. Membranes were washed four times in TBST. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using a chemiluminescent substrate (ECL-Plus, GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) for 5 min. Images were captured on Hyblot CL film (Denville, Scientific Inc, Metuchen, NJ). Optical density analysis of signals was performed using ImageQuant software from Molecular Dynamics (version 5). Equal loading of the blots was shown either by total AKT, PI3 kinase, or β actin.

Cell Viability

Cell viability was measured using the MTT (3(4,5) Dimethyl thiazol-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay as described(25). Cells equivalent to 1×105 mL−1 were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates and incubated for 24 h before treatment as indicated in the results section. Absorbance was measured at 550 nm. Relative cell viability was calculated according to the formula: cell viability (%) = absorbance experimental/absorbance control • 100.

ATP Assay

B6-MCL were cultured to 80% confluency and treated as indicated in each experiment. After completion of experiments cells were collected by scraping and immediately stored in aliquots at −80 °C until measurement. ATP was released using the boiling method, by addition of 300 µL boiling buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.75), 4 mM EDTA) and immediate transfer to a boiling water bath for 2 min (5). Samples were put on ice and sonicated for 10 seconds. Samples were diluted 300-fold and 50 µL were utilized to determine the ATP concentration using the ATP bioluminescence assay kit HS II (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data were standardized to the protein concentration using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad).

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurements

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) of intact cells was measured as described (26) with modifications. Cultured cells were washed with PBS and trypsinized. The protein concentration of cells was adjusted to 0.2 mg/mL in DMEM media without phenol red (Gibco–Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and not supplemented with fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Tetramethylrhodamine-methylester (20 nM) (TMRM, T-668, Molecular Probes–Invitrogen) was added to the cell suspension. As a control, the ΔΨm was dissipated using 1 µM carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and 500 nM oligomycin. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark under slow rotation. Yellow fluorescence (excitation, 532 nm laser; emission, 585 nm; band pass, 42 nm) was measured using a BD FACS Array (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and data were analyzed with WinMDI version 2.9 software.

Measurement of Nitrite

The nitrite concentration in the culture media was used as a measure of NO production (27). After stimulation/incubation, the generation of NO in the cell culture supernatants was determined by measuring nitrite accumulation in the medium using Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide and 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride in 5% H3PO4, Sigma). One hundred µL of culture supernatant and 100 µL Griess reagent were mixed and incubated for 5 min. The absorption was measured in an automated plate reader at 540 nm. Sodium nitrite (NaNO2, Sigma) was used to generate a standard curve for quantification. Background nitrite was subtracted from the experimental values. Results for each condition were obtained from three separate measurements of identically treated wells, and the data are derived from four independent experiments.

Enzyme- Link Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Murine TNF-α, and IL-6 cytokine levels were measured in cell culture supernatants according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ELISA DuoKits, R&D Systems) as previously described (25).

Measurement of Cytochrome c Oxidase Activity

After appropriate treatments of cell homogenates in incubation buffer (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM K-HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgSO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM PMSF, 10 mM KF, 2 mM EGTA, 2 µM oligomycin), COX activity was analyzed in a closed 200 µL chamber equipped with a micro Clark-type oxygen electrode (Oxygraph system, Hansatech) as previously described (5). Measurements were performed in the absence of nucleotides. Measurements were carried out with 2 µM COX at 25 °C in the presence of 20 mM ascorbate and increasing amounts of cow heart cytochrome c from 0–40 µM. Oxygen consumption was recorded and analyzed with the Oxygraph plus software. Turnover number is defined as consumed O2 [µM]/min/protein [mg](5). Protein concentration was determined with the DC protein assay kit (Bio-rad).

Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Measurements

Cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of wortmannin for different time points. As positive control, cells were treated with antimycin A (5µM) for 30 min. To measure mitochondrial ROS (mROS) cells were incubated with MitoSOX (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 1µM in the dark for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed three times in PBS, and immediately re-suspended in cold PBS and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. MitoSOX Red was excited by laser at 488 nm, and the data collected at FSC, SSC, 585/42 nm (FL2) and 670LP (FL3) channel. Experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Data presented as fold change in mean intensity of MitoSOX fluorescence when compared with PBS alone.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase/Real Time-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using Stat 60 (Iso-Tex Diagnostics, Friendswood TX) and reverse transcribed using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI). The primers for amplification of T-fam, AKT, PGC1, NRF-1, COX IV, and a reference gene (β actin) were used to amplify the corresponding cDNAs. Using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) quantitative analysis of mRNA expression was performed with a MX3000p instrument (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA). PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 20 µL containing 2 µL of total cDNA and 20 pg primers (Invitrogen). The PCR amplification protocol consisted of an initial incubation step for 10 min at 95° C, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95° C for 10 s, annealing for 20 s at 60° C, and extension at 72° C for 20 s. Relative mRNA levels were calculated after normalizing to β-actin. Data were analyzed using the unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test and the results were expressed as relative fold change.

Primer Sequences were β actin Forward 5’-GATTACTGCTCTGGCTCCTAGC-3’ and

Reverse 5’-GACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTGC-3’;

Cytochrome C Oxidase IV Forward 5’-AGTTCAGTTGTACCGCATCCAG-3’ and

Reverse 5’-GGGCCATACACATAGCTCTTCT-3’;

NRF-1 Forward 5’-CCATCTATCCGAAAGAGACAGC-3’ and

Reverse 5’-GGGTGAGATGCAGAGTACAATC-3’;

PGC-1 Forward 5’- GAA GGC CGT GTG GTA TAC ATT C-3’

Reverse 5’- CTG GCC TCT TTT ACT TCT CGT C-3’ and

T-fam Forward 5’-CCTGAGGAAAAGCAGGCATA-3’ and

Reverse 5’-TCACTTCGTCCAACTTCAGC-3’.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc; Chicago, Illinois, USA). One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and post hoc repeated measure comparisons (least significant difference (LSD)) were performed on all obtained data. ELISA, MTT, ROS and qRT-PCR results, which were expressed as mean ± SEM. For all analyses, two-tailed p-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

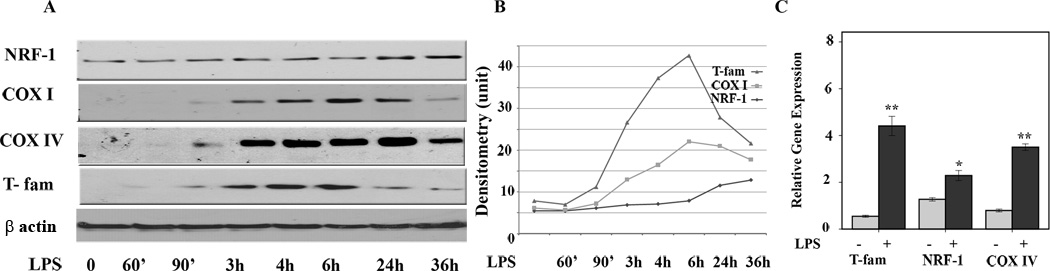

LPS treatment induces cytochrome c oxidase upregulation at the gene and protein level

As macrophages play a central role in recognition of TLR ligands and initiating inflammatory responses as well as ROS production, we have chosen murine macrophages to determine the effects of LPS on the ETC. To show reproducibility in independent systems most experiments were done in two different cell lines. Murine macrophage cells (B6-MCL) were generated as previously described (19). We also confirmed the results using RAW 264.7. In all experiments, cells were grown to reach 80% confluency. B6-MCL cells were treated with 100 ng/mL ultrapure LPS (to assure only TLR4 mediated signaling) for different time periods as indicated. Since the exact effects of LPS on the ETC and mitochondrial transcription factors in immune cells is unknown, we first investigated the kinetic responses of important members of the ETC, including COX subunits I and IV, as well as mitochondrial transcription factors NRF-1 and T-fam, in response to LPS stimulation. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting using specific antibodies against COX subunits I (mitochondrially encoded) and IV (nuclear encoded), NRF-1, and T-fam. As shown in figure 1 panel A, LPS induced expression of both subunits of COX in a time-dependent manner. We observed increased protein expression for COX I/IV starting at 3h after LPS challenge, while increased expression of T-fam was observed as early as 90 min after treatment. LPS stimulation only had a minimal effect on NRF-1 protein expression at a later time point (after 24h, Fig. 1A). Panel B summarizes the densitometric analysis of 4 different experiments. These data indicate that LPS increased protein expression of COX and that there was a time dependent protein expression of mitochondrial transcription factors in response to LPS. To assess the dose dependent upregulation of COX I, we treated cells with different log concentrations of LPS for 6h. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows a dose dependent but non-linear response to LPS in terms of COX I upregulation. Figure 1 panel C shows means of relative gene expression for T-fam, COX IV, and NFR-1 after 2h LPS treatment. Although relative gene expression increased in response to LPS for all these genes, there was more variation in terms of protein expression as determined by immunoblotting, suggesting post-transcriptional regulation, a regulatory mechanism that seems to be important in mitochondria-related genes (28).

Figure 1. Time dependent effect of LPS on mitochondrial transcription factors (NRF-1, T-fam) and cytochrome c oxidase subunit I and IV.

Murine macrophages (B6-MCL) were cultured in a density of 2×106 per well 24 h prior to LPS treatment. Cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for different time periods. A. Whole cell extracts were prepared and 30 µg of total protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using antibodies against COX subunit I, IV and NRF-1 and T-fam. Equal loading was determined using β actin. Cells responded to LPS stimulation with an early increase in expression of T-fam followed by increased expression of both COX subunits (I and IV). NRF-1 increased at a later time point (24h). B. Densitometric analysis (mean) of NRF-1, COX I and IV, and T-fam of 4 independent experiments. C. Relative gene expression for T-fam, COX IV and NRF-1 in response to LPS. Cells were treated with LPS (100ng/mL) for 2h, RNA was isolated and qRT-PCR was carried out for T-fam, NRF-1 and COX IV. Values were normalized to β actin. Results represent mean values of 4 independent experiments each performed in triplicates. Using ANOVA Mann-Whitney U test p<0.05 was considered significant. * denotes a p-value <0.05 and ** expresses a p-value of <0.001.

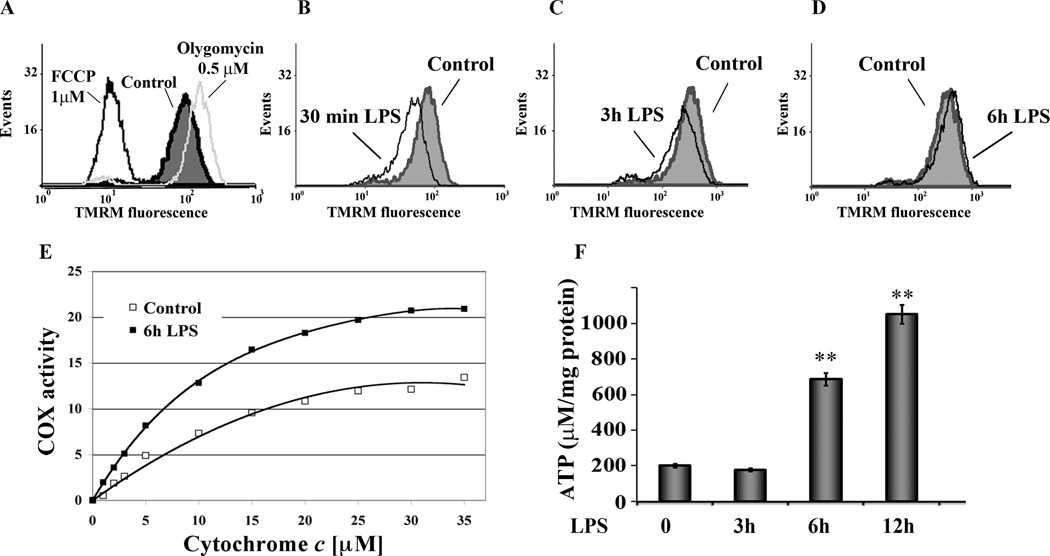

LPS alters mitochondrial membrane potential, COX activity and ATP production

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is generated through pumping of protons across the mitochondrial inner membrane by ETC complexes I, III, and IV (COX) producing the proton motive force utilized by ATP synthase to generate ATP. Previous studies have shown that ΔΨm of monocytes is decreased in severe sepsis and that this is associated with cell death (29). We analyzed the kinetic of ΔΨm in response to LPS treatment using a membrane potential sensitive fluorescent probe (TMRM) and flowcytometry. As controls, the ΔΨm was dissipated using 1 carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) resulting in a left shift of TMRM fluorescence or increased using 0.5 µM oligomycin with a right shift of fluorescence probe (Fig.2A). LPS treatment led to an early (at 30 min) reduction in TMRM fluorescence indicating a decreased ΔΨm followed by a recovery of ΔΨm starting at 3h post LPS treatment (Fig. 2B and C). At 6h post LPS treatment ΔΨm recovered and was even slightly higher compared to untreated cells (Fig. 3C), consistent with increased protein expression for COX subunits at this time point (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 2. LPS effect on mitochondrial membrane potential, COX activity and ATP production.

A. As control cells were treated either with FCCP (1µM) to dissipate ΔΨm resulting in a left shift of TMRM fluorescence or treated with 0.5 µM oligomycin to increase ΔΨm showing a right shift of fluorescence probe. All measurements were performed with a FACScan (Becton-Dickinson) flow cytometer equipped with a yellow fluorescence (excitation, 532 nm laser; emission, 585 nm; band pass, 42 nm) analyzing 10,000 cells in each run. Data obtained were analyzed with the Cell Quest software (n = 4). TMRM fluorescence was normalized to MitoTracker red fluorescence, a membrane potential-independent mitochondrial marker in these cells. B, C and D. Kinetic of ΔΨm in response to LPS treatment. Cells were incubated with LPS (100 ng/mL), and relative membrane potentials were determined using the fluorescent probe TMRM. 30 min LPS treatment led to an early decrease of ΔΨm (B) and recovery starting after 3h treatment (C). After 6h of LPS treatment cells showed an increase in fluorescent signal suggesting recovery of mitochondrial mass and function (D).

E. LPS increased COX activity. B6-MCL cells were cultured with or without LPS (100ng/mL). COX activity was measured 6h after LPS treatment in solubilized cells by the addition of increasing amounts of cytochrome c. Specific activity (TN, turnover number) is defined as consumed O2 ((µmol)/(min⋅total protein (mg)). Shown are representative results of three independent experiments.

F. Time dependent changes of ATP levels in response to LPS. B6-MCL cells were incubated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for different time points as indicated. ATP concentrations were measured using the bioluminescence method. As indicated LPS treatment led to a time-dependent increase of ATP concentration. Using ANOVA Mann-Whitney U test p<0.05 was considered significant. ** expresses a p-value of <0.001.

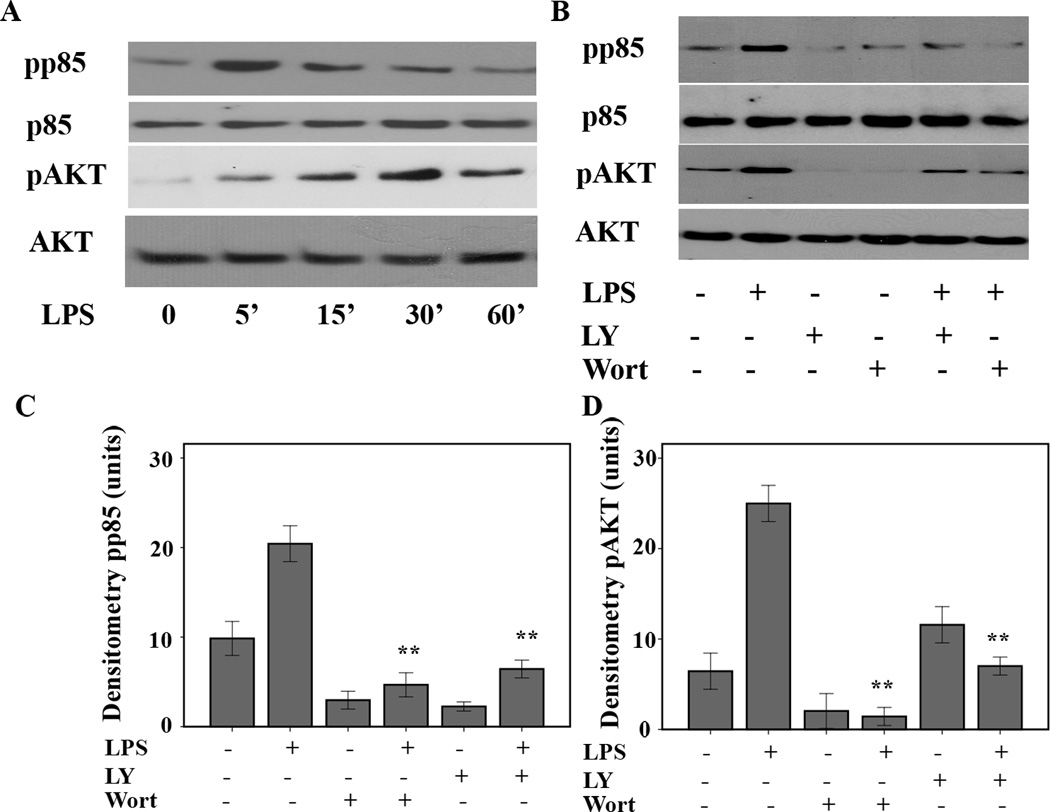

Figure 3. LPS treatment activates the PI3 kinase/AKT pathway in murine macrophages.

A. Murine macrophages (B6-MCL) were cultured and treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for different time points. Total cell lysates were prepared and 20 µg of total cellular proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using phosphoepitope-specific PI3K p85 (Tyr 458/p55 Tyr199) and AKT (Ser 473) antibodies. Equal loading of protein was confirmed using total p85 and AKT antibodies. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. LPS treatment led to an early phosphorylation of the PI3K p85/AKT pathway. B. Murine macrophages (B6-MCL) were treated with LY294002 (50 ng/mL) or wortmannin (100 ng/mL) 30 min prior to LPS (100 ng/mL) stimulation. Thirty min after LPS stimulation, total cell lysates were prepared and 20 µg of total cellular protein were subjected to Western blot analysis using phosphoepitope-specific PI3K detecting dual phosphorylation sites on p85 (Tyr 458/ p55 Tyr199) and AKT (Ser 473). Equal loading of protein was confirmed using total AKT and p85 antibodies. Both inhibitors blocked the effect of LPS on phosphorylation of p85 and AKT. Panel C and D are the densitometric analyses (mean ± SEM) of phosphorylated form of p85 and AKT in response to LPS treatment in presence and absence of wortmannin and LY294002. Using ANOVA Mann-Whitney U test p<0.05 was considered significant. * denotes a p-value <0.05 and ** expresses a p-value of <0.001.

Next, we asked the question whether LPS-mediated increase in protein expression for COX I/IV are associated with a change in both the activity of COX and changes of ATP content of cells. Murine macrophages (B6-MCL) were cultured in the presence of LPS (100 ng/mL) for 6h as COX I and T-fam levels peaked at that time point (Fig. 1E). After solubilization, COX activity was measured by adding increasing amounts of its substrate cytochrome c. As shown in Fig. 2E, LPS treatment led to a 56% increase of COX activity at maximal turnover.

To further assess the link between the change of protein expression in response to LPS treatment and changes in ΔΨm, we measured the ATP content of B6-MCL cells. Figure 2F shows the time dependent changes of ATP levels after LPS treatment of B6-MCL cells with a significant increase of ATP after 6h and a further increase after 12h. At 3h ATP levels were slightly decreased, then increased more than three-fold and five-fold after 6h and 12h, respectively. These data confirm the relationship between cellular ATP and mitochondrial OxPhos capacity represented in form of COX activity and expression.

LPS treatment activates both PI3 kinase and AKT

The PI3 kinase and AKT pathways are involved in many important cellular processes including cell growth, cell survival, and apoptosis (30). Because of the central role of mitochondria as mediators of cell survival and apoptosis, we investigated the effect of LPS-mediated AKT activation on the upregulation of T-fam as well as COX I. First, we examined the time dependent phosphorylation of PI3 kinase and AKT. B6-MCL cells were challenged with LPS (100 ng/mL) for different time points as indicated (Fig. 3A). Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using a specific antibody against the phosphorylated form of the regulatory domain of PI3 kinase (phospho p85) and an antibody detecting the serine 473-phosphorylated form of AKT1. Figure 3A shows rapid phosphorylation of p85 5min after LPS challenge followed by AKT phosphorylation on serine 473. Next we explored specific inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT pathway and their effect on LPS mediated p85 and AKT phosphorylation. B6-MCL cells were treated either with LY294002 or wortmannin 30min prior to LPS challenge or kept in media without treatment. Figure 3B shows that both inhibitors LY294002 and wortmannin prevented phosphorylation of p85 and AKT, indicating that LPS-induced AKT phosphorylation is PI3K-dependent.

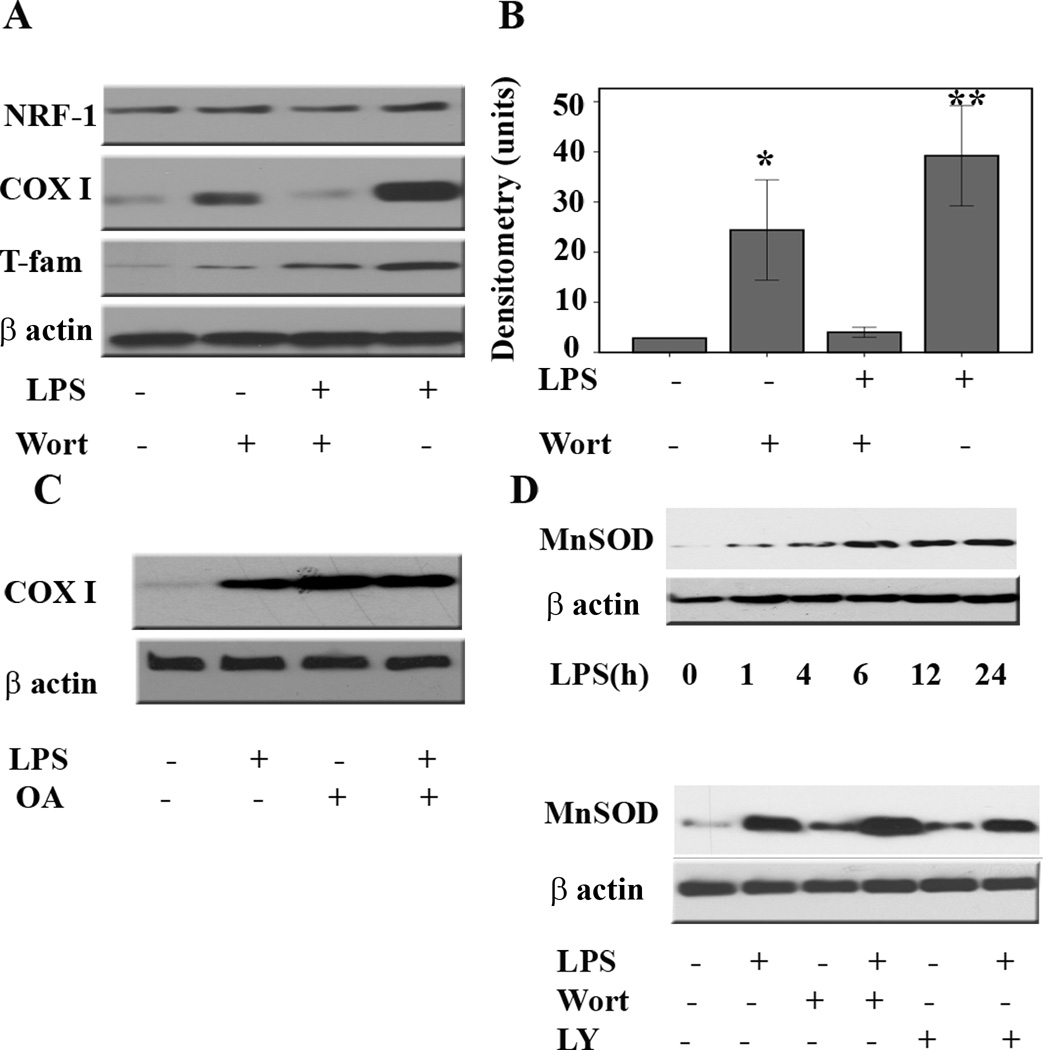

Inhibition of the PI3 Kinase/AKT pathway abrogates LPS-mediated upregulation of COX and T-fam

We next assessed the effect of inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway on protein expression for COX I and T-fam. B6-MCL cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO), LY294002, or wortmannin 30min prior to LPS challenge. Immunoblotting on total cell lysates was performed using specific antibodies against NRF-1, COX I, and T-fam. Figure 4 shows that pretreatment with wortmannin inhibited LPS-mediated upregulation of both COX I and T-fam with a minimal effect on NRF-1 expression. Similar results were observed in the presence of LY294002 (Supplementary Fig. 2). We observed an increase in expression for both proteins when cells were exposed to wortmannin or LY294002 alone. In the presence of AKT inhibitors, however, LPS mediated protein expression for T-fam and COX I was strongly diminished. These data suggest that the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway is required for LPS-mediated upregulation of COX subunit I and T-fam. It is known that the protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) plays a pivotal role in dephosphorylation of AKT and thereby diminishing its activity (31). To confirm that phosphorylation of AKT plays a critical role in LPS mediated upregulation of COX I and T-fam, we evaluated the effect of a PP2A inhibitor (okadaic acid) to prevent the dephosphorylation of AKT. Cells were incubated with okadaic acid (1nM) 30min prior to LPS treatment for different time points. As expected, okadaic acid treatment led to AKT phosphorylation alone and to a prolonged activation of AKT in the presence of LPS (data not shown). Next we evaluated the effect of okadaic acid in the presence and absence of LPS on COX I. Okadaic acid pretreatment led to an enhanced LPS effect in terms of COX I upregulation (Figure 4C), supporting the role of active AKT in this process.

Figure 4. Inhibition of the PI3 kinase/AKT pathway abrogates LPS-mediated upregulation of COX I and T-fam but not manganese superoxide dismutase.

A. Murine macrophages (B6-MCL) were pretreated with wortmannin (100 ng/mL) for 30 min prior to adding LPS (100 ng/mL) to the media for 6 h. After incubation, whole cell extracts were prepared and 20 µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis for NRF-1, COX I, T-fam, and β actin as loading control. B. Densitometric analysis (mean ±SEM) of COX I in 4 independent experiments in response to LPS stimulation in the presence of wortmannin. Using ANOVA Mann-Whitney U test p<0.05 was considered significant. * denotes a p-value <0.05 and ** expresses a p-value of <0.001. C. Murine macrophages (B6-MCL) were pretreated with okadaic acid (10 nM) 30 min prior to adding LPS (100 ng/mL) to the media for 6 h. After incubation, whole cell extracts were prepared and 20 µg of total protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using an antibody against COX I, β actin was used to confirm equal loading. The figure is a representative of four independent experiments. D. Upper panel. Time dependent expression of MnSOD in B6-MCL cells. Cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for different time periods as indicated. Total cell lysates were prepared and 20 µg of protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using an antibody against MnSOD. D. Lower panel. Murine macrophages (B6-MCL) were pretreated with wortmannin (100 ng/mL) or LY294002 (50 ng/mL) for 30 min prior to adding LPS (100 ng/mL) to the media for 6 h. After incubation, whole cell extracts were prepared and 20 µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using an antibody against MnSOD. Equal loading was assessed using a β actin antibody. The presence of wortmannin or LY294002 did not abrogate LPS-mediated upregulation of MnSOD.

To further confirm that the AKT pathway is a distinct intracellular signal and specific to LPS-mediated upregulation of COX I and T-fam, we assessed the effect of LPS challenge in the presence and absence of LY294002 or wortmannin on manganese superoxidase dismutase (MnSOD). MnSOD, a vital anti-oxidant enzyme localized to the mitochondrial matrix, catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide anions to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). It has been shown that LPS challenge leads to rapid induction of MnSOD at the transcriptional and protein levels (32, 33). As rapid upregulation of the mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins in response to LPS is associated with increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (34), we investigated the effect of LPS on MnSOD protein expression. We confirmed in our experimental model that LPS challenge leads to rapid induction of MnSOD (Fig. 4 D). Although it has been shown that MnSOD expression is associated with mitochondrial ROS production during inflammation, the signaling pathways responsible for such a response are still unclear. We thus assessed the effect of LPS on MnSOD expression in the presence or absence of LY294002 or wortmannin. B6-MCL cells were cultured and pretreated with either inhibitor for 30min prior LPS treatment. A 6h LPS treatment duration was chosen as it produced a robust induction of MnSOD as well as COX I expression. MnSOD expression was analyzed by immunoblotting of total cell lysates using a specific antibody. As shown in figure 4E, neither of the two inhibitors prevented the LPS-mediated protein expression for MnSOD. Interestingly, the presence of wortmannin alone induced MnSOD, and a similar effect was found for LY294002. These data suggest that LPS-mediated upregulation of MnSOD versus COX I and T-fam occurs through distinct intracellular signal transduction pathways independent of the PI3K/AKT pathway.

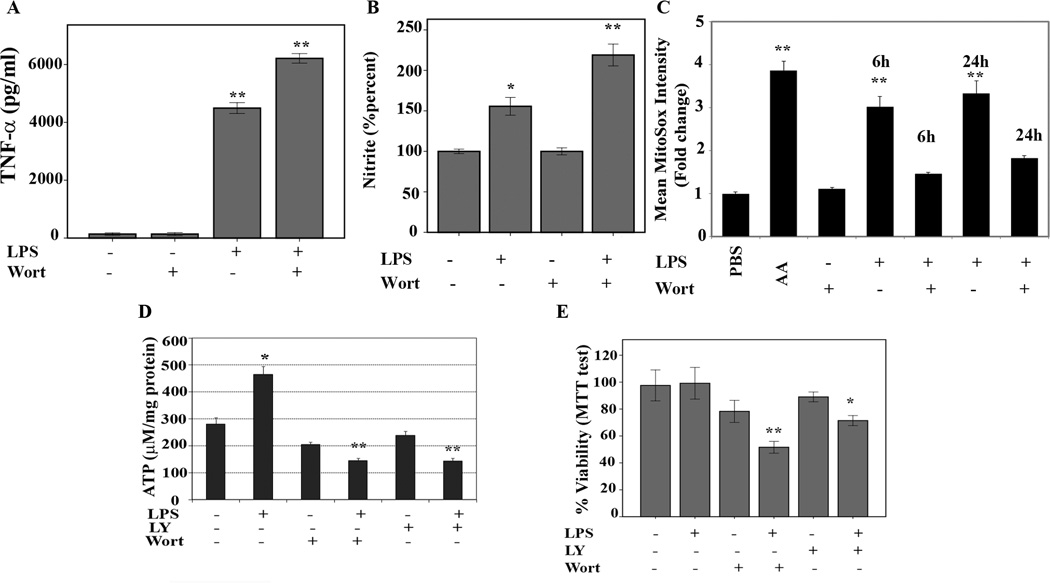

AKT inhibition and failure of COX I and T-fam upregulation in response to LPS is associated with increased TNF-α, nitric oxide, and cell death, and decreased ROS and ATP levels

It has been suggested that the AKT pathway can play a positive as well as negative role in TLR-mediated cytokine production (11, 13). We investigated the effect of AKT inhibition on the response of LPS stimulation in our cell system. LPS stimulation (100 ng/mL for 24 h) enhanced TNF-α secretion in supernatants, but secretion of TNF-α was significantly higher (p<0.05) in pretreated cells with wortmannin (Fig. 5A). Some studies suggested that nitric oxide may induce mitochondrial biogenesis (NRF-1, T-fam, and COX) and MnSOD expression (35, 36). Hence, we investigated whether the inhibition of the AKT pathway in LPS-stimulated macrophages changes the nitric oxide (NO) levels in these cells. Figure 5B shows the effect of LPS in the presence and absence of wortmannin on cumulative nitrite production 24h after LPS treatment as an indirect measure of NO production. As expected, LPS treatment alone resulted in a 50% increase of nitrite levels. Interestingly, wortmannin alone had no effect on nitrite production whereas wortmannin or LY294002 (Fig. 4A and Suppl. Fig.2) in combination with LPS led to a two-fold increase in nitrate levels. LPS stimulation of macrophages induces production of ROS such as peroxides and superoxide. ROS play an important role in cellular functions via the activation of signaling cascades and it has been suggested that ROS affect mitochondrial biogenesis, morphology, and function (37). Hence, we investigated the effect of LPS stimulation in the presence and absence of wortmannin on the production of mitochondrial ROS in form of superoxide. To detect mitochondrial ROS (mROS), we further investigated the effect of LPS in the presence or absence of wortmannin using a fluorescence dye (MitoSox) that measures predominantly mitochondrial superoxide(3). As shown in Figure 5C, LPS treatment led to a time dependent augmentation in mROS, which co-incited with increased COX as well as mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 1 and Fig.2). The presence of wortmannin reduced mROS. However, this mROS reduction was associated with increased cell death (Fig. 5). These data suggest that mitochondrial biogenesis is required for mROS production. By inhibiting the AKT pathway, mitochondrial regeneration is diminished leading to a decreased mROS production and increase in cell death. Next we assessed whether the inhibition of the AKT pathway translates into changes of ATP content of the cells. B6-MCL cells were cultured and pretreated for 30min with either LY294002 or wortmannin before stimulation with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 6h. As shown in figure 5D, ATP levels were significantly decreased in the presence of both inhibitors (LY294002 or wortmannin), whereas LPS treatment led to an increase in cellular ATP content. To further explore the biological effect of inhibition of AKT and subsequent failure of upregulation of protein expression for COX I and T-fam, we assessed cell viability using the tetrazolium dye (MTT) assay (25). Figure 5E shows that LPS treatment alone at the concentration applied throughout this study did not change viability. Using AKT pathway inhibitors LY294002 or wortmannin led to a minimal decrease in cell viability, whereas LPS challenge in the presence of AKT pathway inhibitor led to a significant loss of cell viability (p<0.001). Collectively these data suggest that LPS-mediated upregulation of COX requires PI3K/AKT activation and that this activation is important in the prevention of cell death and excessive proinflammatory mediators (NO and TNF-α).

Figure 5. Effect of LPS and PI3Kinase inhibitor on cellular ATP and nitrite levels, ROS production, and cell viability.

A. B6-MCL cells were pretreated with wortmannin (100 ng/mL) for 30 min prior to adding LPS (100 ng/mL) or kept in media for 24 h. Supernatants were analyzed for TNF-α via ELISA. Data are presented as means of four independent experiments and error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. (p< 0.01). B. Cumulative nitrite levels in the supernatant were measured as described in Material and Methods. Data presented as mean ±SEM of % changes of untreated cells. Using ANOVA Mann-Whitney U test p<0.05 was considered significant. * denotes a p-value <0.05 and ** expresses a p-value of <0.001. C. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) were measured using the probe MitoSox. As positive control cells were treated with antimycine A (AA) for 30 min prior to treatment with the MitoSox fluorescence probe. Cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) in presence and absence of wortmannin (100 ng/mL). The data presented as fold change in mean intensity of MitoSOX fluorescence compared to PBS plus MitoSOX alone (negative control). LPS treatment led to a time dependent increase of mROS after 6 and 24h. Pretreatment of cells 30 min. prior to LPS stimulation led to a significant decrease in mROS production. Using ANOVA Mann-Whitney U test p<0.05 was considered significant. * denotes a p-value <0.05 and ** expresses a p-value of <0.001. D. Murine macrophages (B6-MCL) were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 6h in the presence or absence of wortmannin (100 ng/mL) or LY294002 (50 ng/mL) 30 min prior to LPS treatment. ATP concentrations were measured using the bioluminescence method. ATP levels increased in response to LPS. Pretreatment with wortmannin or LY294002 abrogated the LPS-mediated ATP upregulation. Data presented is the result of 3 independent experiments measured in triplicates. Using ANOVA Mann-Whitney U test p<0.05 was considered significant. * denotes a p-value <0.05 and ** expresses a p-value of <0.001. E. Cell viability. 2×105 B6-MCL cells were plated in 96 well plate and treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24h in the presence or absence of wortmannin (100 ng/mL) or LY294002 (50 ng/mL). Cell viability was assessed using MTT assay. Data presented as mean ±SEM of % changes of untreated cells. Using ANOVA Mann-Whitney U test p<0.05 was considered significant. * denotes a p-value <0.05 and ** expresses a p-value of <0.001.

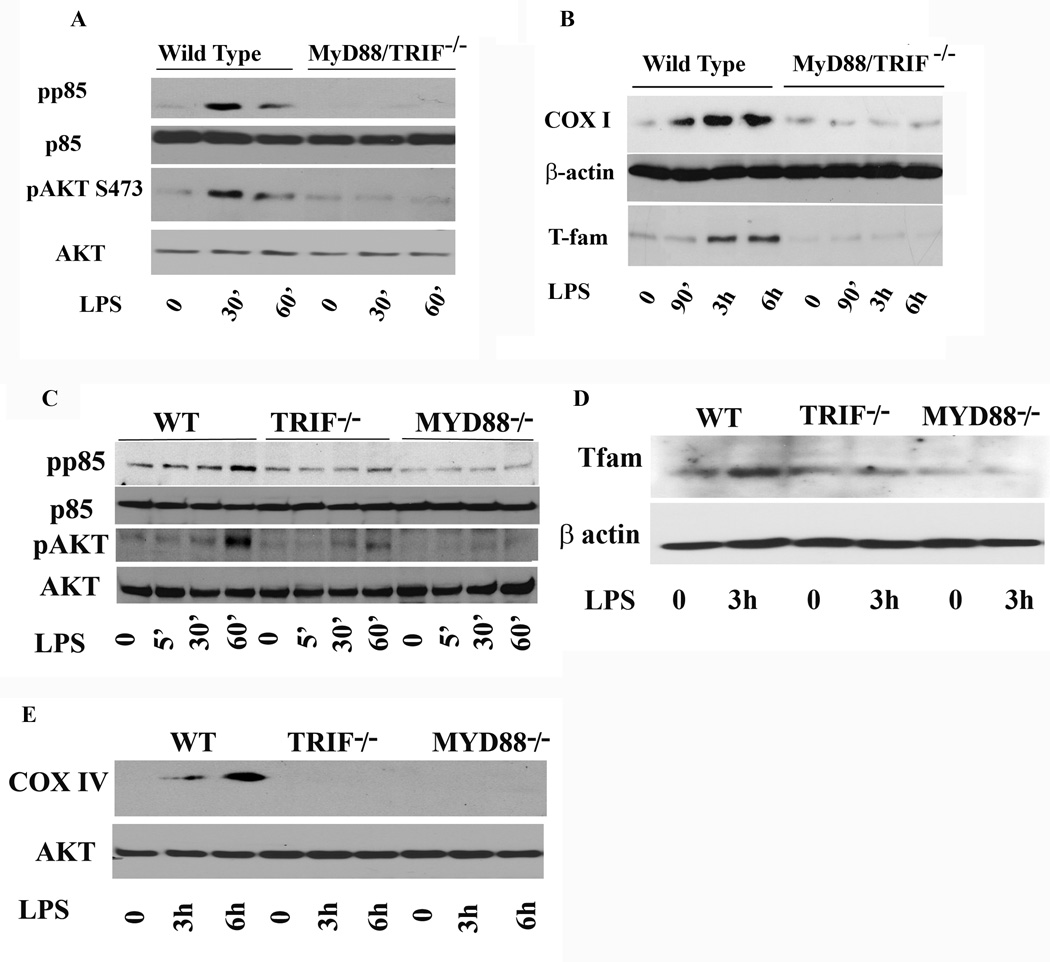

LPS-mediated AKT activation and subsequent COX I and T-fam upregulation is MYD88/TRIF-dependent

Although several studies have shown that LPS stimulation leads to PI3K/AKT activation, the mechanism by which LPS activates AKT is not well understood and remains controversial. Additionally, PI3K/AKT pathway activation can occur in response to diverse growth factors and ligand stimulation though diverse receptor activation (30). Macrophages from MyD88/TRIF−/− mice are defective in many TLR4-mediated responses, such as LPS-induced secretion of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β) (38). A previous study has shown that LPS mediated AKT activation is TLR4/MyD88-dependent and requires PI3K activation (13). Therefore, we assessed whether the LPS mediated increased expression for COX I and T-fam requires MYD88/TRIF adaptor proteins. Phenotypes of wild type and MyD88/TRIF−/− cells were verified by a range of functional parameters, including responsiveness to TLR4 and cytokine production (Supplementary Fig.3). We stimulated side by side WT and MYD88/TRIF−/− cells with LPS for different time points to assess AKT activation. Figure 6A shows phosphorylation of p85 and AKT in response to LPS stimulation in WT and MyD88/TRIF−/−. As shown, WT cells responded to LPS stimulation with phosphorylation of PI3K as well as AKT on serine 473, whereas no phosphorylation of either kinases were observed in MyD88/TRIF−/− macrophages. These data suggest that LPS-induced activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway is dependent on the presence of MyD88/TRIF adaptor protein. To determine whether the lack of AKT activation in MYD88/TRIF−/− would parallel the effect on LPS-mediated T-fam and COX I expression, we stimulated WT and MyD88/TRIF−/− cells side by side with LPS for different time points (90 min, 3h, and 6h). As shown in figure 6B, WT cells responded to LPS treatment with increased expression of both T-fam and COX I, while MYD88/TRIF−/− cells failed to upregulate either one of them. These data suggest that LPS-induced phosphorylation of AKT on serine 473 requires the presence of MyD88 and TRIF adaptor proteins and that the LPS-induced expressions of T-fam and COX I require activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Next, we asked whether absence of either MyD88 or TRIF would be sufficient to prevent LPS- mediated PI3K/AKT pathway activation and subsequent T-fam and COX expression. BMDMs from WT and macrophages deficient for either MyD88 or TRIF were stimulated with LPS for the indicated times. As shown, LPS-mediated PI3K/AKT pathway activation required both MyD88 and TRIF. In macrophages lacking TRIF, we observed an attenuated and delayed response in AKT phosphorylation, while cells lacking MyD88 did not respond to LPS with AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 6C). Similarly, WT macrophages responded to LPS with an increased expression for T-fam (Fig. 6D) and COX IV (Fig. 6E), while macrophages deficient in MyD88 or TRIF did not increase expression for T-fam and COX (Fig. D and E).

Figure 6. LPS induced COX I and T-fam expression is MyD88/TRIF dependent.

A. Wild type murine macrophages (WT) and MyD88−/− TRIF−/− cells were cultured side by side in the presence and absence of LPS (100 ng/mL) for 30 or 60 min. Total cell lysates were prepared and 20 µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using phosphoepitope-specific antibodies for p85 and AKT (serine 473). Equal loading of protein was confirmed using total p85 and AKT antibodies. B. Wilt type murine macrophages and MyD88/TRIF−/− cells were cultured side by side in the presence and absence of LPS for 90 min, 3h and 6h. Total cell lysates were prepared and 20 µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using antibody against T-fam and COX I. Equal loading of protein was confirmed using β-actin antibody. Wild type cells responded to LPS stimulation with a significant increase in T-fam starting at 90 min throughout 6h post treatment with LPS. Upregulation of COX I in wild type was seen starting at 3h after LPS stimulation. In contrast, MyD88/TRIF−/− cells did not respond to LPS with increased expression for T-fam and COX I.

C. Bone marrow derived macrophages isolated from wild type (WT), TRIF or MYD88 deficient mice were cultured in parallel with LPS for 5, 30 and 60 min. Total cell lysates were prepared and 20 µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using phosphoepitope-specific antibodies for p85 and AKT (serine 473). Equal loading was confirmed using total AKT and total p85 antibodies. LPS treatment evoked a weak and delayed AKT phosphorylation in TRIF−/− cells but MYD88 deficient cells did not show any response to LPS treatment. D. Bone marrow derived macrophages isolated from WT, TRIF or MYD88 deficient mice were either kept in media or treated with LPS for 3h. Twenty µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using T-fam antibody. Equal loading was confirmed using β actin antibody. While LPS treatment led to an increase in T-fam expression in WT, neither TRIF−/− and MyD88−/− cells responded with an increased expression for T-Fam. E. Bone marrow derived macrophages isolated from WT, TRIF or MYD88 deficient mice were either kept in media or treated with LPS for 3h and 6h. Twenty µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using a COX IV antibody. Equal loading was confirmed using total AKT antibody. While LPS treatment led to an increase in COX IV expression in WT after 6h, TRIF−/− and MyD88−/− cells did not show any expression of COX IV.

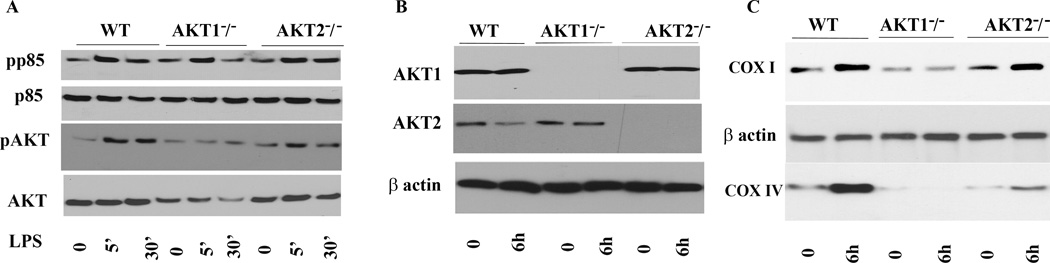

Expression of AKT1 is pivotal in LPS-mediated COX upregulation in bone marrow derived macrophages

Three AKT isoforms have been described with distinct biological functions. To further investigate mechanistically which AKT isoform plays a major role in the LPS response and mitochondrial biogenesis in macrophages, we utilized cells derived from knockout mice lacking AKT1 or AKT2. While AKT1 and AKT2 are ubiquitously expressed, including immune cells, endothelial cells and in hematopoietic cells, AKT3 expression is largely confined to the testes and brain (39–41). Thus we focused on AKT1 and AKT2 isoforms. BMDMs from mice deficient in AKT1, AKT2, or WT mice were cultured side by side under equal conditions. Cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for different time points and whole cell extracts were subjected to immunoblotting. As seen is Fig. 7A, LPS stimulation of BMDMs isolated from WT AKT1−/−, and AKT2−/− led to rapid phosphorylation of p85 and AKT phosphorylation on phospho-serine 473. This antibody detects phosphorylated AKT on serine 473 regardless of the isoforms expressed (either AKT1, AKT2 or AKT3). Next, we used isoform specific AKT1 and AKT2 antibodies to detect the level of AKT1 and AKT2 expression in WT, AKT1−/− and AKT2−/− BMDMs. Figure 7B confirmed the lack of expression of AKT1 protein in AKT1−/− and of AKT2 in AKT2−/− macrophages, respectively. As described earlier, in our cell model we detected the highest expression for COX 6h after LPS treatment. Thus immunoblotting was done using the 6h time point after LPS treatment. Figure 7C shows that the cells lacking AKT1 had severe impairment in COX I and COX IV expression at baseline as well as in response to LPS. In contrast, the induction of COX I was unimpaired in response to LPS treatment in AKT2−/− macrophages (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, the basal level of COX IV was lower in these macrophages as compared to those of WT, but AKT2−/− macrophages responded to LPS with an enhanced expression for COX IV. These findings indicate that the AKT1 isoform plays a central role in LPS mediated COX I and IV, while AKT2 contributes only to COX IV upregulation by LPS in BMDMs.

Figure 7. Critical role of AKT1 in LPS mediated COX expression.

Bone marrow derived macrophages were isolated from WT, AKT1 or AKT2 deficient mice, cultured under equal conditions and treated with LPS for different time points as indicated.

A. Detection of phospho p85 and AKT. Twenty µg of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using phosphoepitope-specific antibodies for p85 and AKT (serine 473). Equal loadings were confirmed using either total p85 or total AKT antibodies. B. Detection of AKT isoforms. Immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysate performed using antibodies detecting AKT1 and AKT2. Equal loading was confirmed using β actin antibody. As shown AKT1−/− macrophages lack expression of AKT1 while AKT2−/− macrophages lack AKT2. C. Bone marrow derived macrophages isolated from WT, AKT1−/−, and AKT2−/− mice kept in media or treated with LPS for 6h. Immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysate performed using antibodies detecting COX I (upper panel) and COX IV (lower panel). Equal loading was confirmed using β antibody. Cells lacking AKT1 had severe impairment in COX I and COX IV expression at baseline as well as in response to LPS. Induction of COX I was unimpaired in response to LPS treatment in AKT2−/− macrophages. Furthermore, the basal level of COX IV was lower in these macrophages as compared to those of WT, but AKT2−/− macrophages responded to LPS with an enhanced expression for COX IV.

Discussion

Here we analyzed the molecular mechanisms underlying the LPS-mediated upregulation of ETC components focusing on COX and mitochondrial transcription factors (T-fam and NRF-1) as markers of mitochondrial biogenesis. We show that LPS-mediated upregulation of COX and T-fam is dependent on AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 1 and 3) and that inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway leads to abrogation of this effect (Fig. 3). Increased expression of COX subunits I and IV in response to LPS challenge was associated with restoration of COX activity and increased cellular ATP levels (Fig. 2). Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway abrogated the effect of LPS on both COX and T-fam and led to decreased ATP production and increased cell death. We also show that the effect of LPS on both COX and T-fam is dependent on MyD88 and TRIF adaptor proteins. LPS challenge of MyD88/TRIF knock out cells failed to phosphorylate AKT and upregulate T-fam and COX (Fig. 6 A and B). Cells lacking MyD88 did not respond to LPS with AKT activation, while macrophages deficient in TRIF showed a delayed AKT activation (Fig. 6C). Neither MyD88 nor TRIF deficient cells showed an increase in T-fam or COX expression (Fig. 6D and E). These data suggest that MyD88/TRIF is required both for AKT phosphorylation as well as for LPS-mediated increased expression of COX and T-fam. Importantly, macrophages from AKT1−/− mice showed a lack of response to LPS in terms of upregulation of COX I and IV (Fig 7C). These data collectively indicate that AKT1 regulates and maintains the mitochondrial function in response to TLR4 agonists.

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles and essential in providing most cellular ATP. They have emerged as important integrators of several vital signaling cascades (42). Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) builds the proton motive force for generation of ATP through oxidative phosphorylation and is critical for the integrity of mitochondrial function. Bacteria and several bacterial products such as LPS or bacterial toxins have been shown to affect the ΔΨm and alter the OxPhos as well as mitochondrial ROS production (3, 43, 44). We show in this study the dynamic changes of ΔΨm of murine macrophages in response to LPS, an initial decrease of ΔΨm followed by a delayed restoration of ΔΨm that mirrored the upregulation of COX (Fig 1 and 2). This process may be specifically important in the response of macrophages to bacterial products and may facilitate the required energy for cytokine production as well as phagocytic activity of these cells. One recent study found that mitochondrial ROS production in response to specific TLRs is required for phagocytic activity of macrophages (3). Another study found that AKT1 and AKT2 isoforms regulate the intracellular ROS content in hematopoietic stem cells necessary for their function and proliferation(40).

COX biogenesis is a critical part of mitochondrial biogenesis. Among the thirteen subunits of COX, the largest subunits, COX I–III, are encoded by the mtDNA and regulated at the transcriptional level by T-fam (45). COX is the terminal enzyme of the electron transport chain and plays a pivotal role in electron transfer to molecular oxygen and generation and maintenance of ΔΨm and ATP. COX activity as well as expression is tightly regulated by metabolic cellular demand (5, 42). Our laboratory has shown that TNF-α challenge leads to rapid inhibition of COX and this inhibition is due to tyrosine phosphorylation of the catalytic subunit I of COX (5). This finding may explain at least in part the observed metabolic switch from aerobic to glycolytic energy metabolism during sepsis. However, not all septic patients develop organ failure with a poor outcome. Thus, additional mechanisms may be essential for the recovery from sepsis. Our current data indicate that LPS stimulation of murine macrophages leads to 20-fold increase in expression of COX I (Fig. 1A), and that such an increase was associated with a 56% increase in COX activity.

Evidence suggest that non-survivors of sepsis exhibit more extensive mitochondrial damage and failure of cellular energetics compared to survivors as determined from muscle biopsies of critically ill patients (46). Interestingly, Staphylococus aureus induced sepsis in mice with a lower bacterial load led to a recovery from bioenergetic failure with orderly (sequential) induction of NRF-1, NRF-2, PGC-1, and T-fam m-RNAs in the liver of septic animals (47). While animals with sepsis induced with a higher bacterial count failed to recover and exhibited lack of mitochondrial biogenesis. We have observed that treatment of macrophages with a higher dose of LPS (>1µg/ml) failed to increase expression for COX I (Suppl. Fig. 1) and T-fam. In contrast to the observation by Haden et. al. (47), we show expression at both the gene and protein levels that murine macrophages exhibit higher baseline NRF-1 mRNA expression and minimal change in response to LPS treatment as compared to PGC1- α (data not shown), T-fam and COX I and IV. It should be noted, however, that tissue and cell specific differences may exist and that various mitochondria-related transcription factors likely play different roles in specific tissues and cells. Additionally, diverse posttranscriptional modifications of mitochondrial transcription factors such as phosphorylation or redox regulation (for example in the case of NRF-1) have been reported (15). Such events may be important in regulation of mitochondrial transcripts in response to LPS.

Recognition of LPS by TLR4 plays a pivotal role in the initiation of Gram negative sepsis and septic shock through diverse inflammatory processes in mammals. LPS challenge leads to activation of diverse cell signaling pathways such as inflammatory, apoptotic, but also pro-survival pathways. It has been shown that LPS challenge results in activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, which is required for activation of survival pathways (48). Both PI3K and AKT pathway activation have been reported to be associated with TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR5 in different cells (13, 49). Although it has been suggested that the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway has a negative regulatory function on TLR ligation, the level of interaction between the TLRs and the PI3K/AKT pathway is not well understood (13, 49, 50). Several studies suggested that the inhibition of this pathway leads to decreased phosphatase activity resulting in an increased production of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β and IL-6 with an adverse effect on cell survival (11). Our data indicate that inhibition of AKT pathway in presence of LPS increases proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α), ROS, NO and decreased cell survival in murine macrophages and these findings paralleled the lack of mitochondrial biogenesis. Although, we have observed increased ROS (both cellular as well as mROS) in response to LPS, the presence of wortmannin led to an increased fluorescence in CM-H2DCFDA (data not shown), but a decrease in the MitoSox signal. We propose that the enhanced CM-H2DCFDA probe in the presence of wortmannin is due to increased peroxynitrite in the cytoplasm due to cell death processes. As shown in Figure 5C, wortmannin led to a decreased mROS, but also increased cell death.

Moreover in macrophages, TLR ligation initiates autophagy, a process that provides metabolic intermediates to maintain bioenergetics necessary to carry out the killing of pathogens and to promote survival (51, 52). It has been shown that mammalian cells with hyperactive AKT accumulate ATP, whereas cells with reduced AKT activity exhibit markedly reduced ATP content (53). Such effects have been explained by the role of activated AKT on mitochondria-associated hexokinase and glycolysis (54). Our data indicate that presence of AKT1 and its activation in response to LPS is critical for the upregulation of mitochondrial complexes, in particular COX. Previously, AKT1 has been implicated as a critical regulator in homeostasis of hematopoietic stem cell function and ROS (40). Interestingly, another study associated the loss of AKT1 with severe atherosclerosis in a mice model of coronary artery disease (55). Macrophages of animals lacking AKT1 were more susceptible to apoptosis and exhibited defective clearance of dead foam cells (55). Our study sheds some light on these observations, because our data mechanistically suggest that suppressed mitochondrial energetics cause an impaired stress response in AKT1−/− macrophages. PI3K is involved in many important cellular pathways including cell growth, migration, and apoptosis (30). It has been shown that the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated in response to growth factors but also in response to TLR ligands (13). However, PI3K activation in absence of AKT1 was not sufficient to upregulate COX in response to LPS. Our results indicate that the PI3K/AKT pathway is required for upregulation of mitochondrial OxPhos as well as T-fam and both processes require the adaptor protein MyD88/TRIF (Fig 6A and B). Previously it has been shown that MyD88 deficient animals exhibit poorer outcome when infected with various microorganisms that was associated with an enhanced bacterial burden (11, 56–58). This paradigm, at least in part, may be explained by their inability to enhance mitochondrial biogenesis in response to microbial stimuli.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Eicke Latz (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA) for providing us the macrophage cell lines.

This work was supported by the Department of Medicine (LS) and the Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics (LS and MH), Wayne State University School of Medicine. This work was supported partly by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK61707 to G.N and RO1 DK56886 to M.J.B.

Abbreviations

- AKT

protein Kinase B

- ETC

electron transport chain

- COX

cytochrome c oxidase

- IL-1β

interleukin 1 beta

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- INFγ

interferon gamma

- PI3kinase

phosphoinositide 3 kinase

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- MAP Kinase

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- OxPhos

oxidative phosphorylation

- T-fam

mitochondrial transcription factor A

- MyD88

adaptor protein myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- TIR

Toll/IL1 receptor

- TRIF

TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β

References

- 1.Doyle SL, O'Neill LA. Toll-like receptors: from the discovery of NFkappaB to new insights into transcriptional regulations in innate immunity. Biochemical pharmacology. 2006;72:1102–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rich P. Chemiosmotic coupling: The cost of living. Nature. 2003;421:583. doi: 10.1038/421583a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West AP, Brodsky IE, Rahner C, Woo DK, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Walsh MC, Choi Y, Shadel GS, Ghosh S. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2011;472:476–480. doi: 10.1038/nature09973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy RJ, Deutschman CS. Cytochrome c oxidase dysfunction in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:S468–S475. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000278604.93569.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samavati L, Lee I, Mathes I, Lottspeich F, Huttemann M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits oxidative phosphorylation through tyrosine phosphorylation at subunit I of cytochrome c oxidase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:21134–21144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801954200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carre JE, Singer M. Cellular energetic metabolism in sepsis: the need for a systems approach. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scarpulla RC. Nuclear control of respiratory chain expression by nuclear respiratory factors and PGC-1-related coactivator. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:321–334. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brealey D, Karyampudi S, Jacques TS, Novelli M, Stidwill R, Taylor V, Smolenski RT, Singer M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in a long-term rodent model of sepsis and organ failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R491–R497. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00432.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang ZJ, Zhang FM, Wang LS, Yao YW, Zhao Q, Gao X. Lipopolysaccharides can protect mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and enhance proliferation of MSCs via Toll-like receptor(TLR)-4 and PI3K/Akt. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:665–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schabbauer G, Luyendyk J, Crozat K, Jiang Z, Mackman N, Bahram S, Georgel P. TLR4/CD14-mediated PI3K activation is an essential component of interferon-dependent VSV resistance in macrophages. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2790–2796. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medina EA, Morris IR, Berton MT. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation attenuates the TLR2-mediated macrophage proinflammatory cytokine response to Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. J Immunol. 185:7562–7572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenny EF, O'Neill LA. Signalling adaptors used by Toll-like receptors: an update. Cytokine. 2008;43:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laird MH, Rhee SH, Perkins DJ, Medvedev AE, Piao W, Fenton MJ, Vogel SN. TLR4/MyD88/PI3K interactions regulate TLR4 signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:966–977. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1208763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajaram MV, Ganesan LP, Parsa KV, Butchar JP, Gunn JS, Tridandapani S. Akt/Protein kinase B modulates macrophage inflammatory response to Francisella infection and confers a survival advantage in mice. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:6317–6324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional paradigms in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:611–638. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gleyzer N, Vercauteren K, Scarpulla RC. Control of mitochondrial transcription specificity factors (TFB1M and TFB2M) by nuclear respiratory factors (NRF-1 and NRF-2) and PGC-1 family coactivators. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1354–1366. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1354-1366.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scarpulla RC. Nuclear control of respiratory gene expression in mammalian cells. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:673–683. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhar SS, Ongwijitwat S, Wong-Riley MT. Nuclear respiratory factor 1 regulates all ten nuclear-encoded subunits of cytochrome c oxidase in neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:3120–3129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707587200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagpal K, Plantinga TS, Sirois CM, Monks BG, Latz E, Netea MG, Golenbock DT. Natural loss-of-function mutation of myeloid differentiation protein 88 disrupts its ability to form Myddosomes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:11875–11882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JH, Kim YG, McDonald C, Kanneganti TD, Hasegawa M, Body-Malapel M, Inohara N, Nunez G. RICK/RIP2 mediates innate immune responses induced through Nod1 and Nod2 but not TLRs. J Immunol. 2007;178:2380–2386. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho H, Mu J, Kim JK, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Crenshaw EB, 3rd, Kaestner KH, Bartolomei MS, Shulman GI, Birnbaum MJ. Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKB beta) Science. 2001;292:1728–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5522.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho H, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Feng F, Birnbaum MJ. Akt1/PKBalpha is required for normal growth but dispensable for maintenance of glucose homeostasis in mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:38349–38352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franchi L, Amer A, Body-Malapel M, Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Jagirdar R, Inohara N, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, Grant EP, Nunez G. Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase- and interleukin 1beta in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:576–582. doi: 10.1038/ni1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samavati L, Rastogi R, Du W, Huttemann M, Fite A, Franchi L. STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation is critical for interleukin 1 beta and interleukin-6 production in response to lipopolysaccharide and live bacteria. Mol Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee I, Pecinova A, Pecina P, Neel BG, Araki T, Kucherlapati R, Roberts AE, Huttemann M. A suggested role for mitochondria in Noonan syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1802:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian Q, Stepaniants SB, Mao M, Weng L, Feetham MC, Doyle MJ, Yi EC, Dai H, Thorsson V, Eng J, Goodlett D, Berger JP, Gunter B, Linseley PS, Stoughton RB, Aebersold R, Collins SJ, Hanlon WA, Hood LE. Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of gene expression in Mammalian cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:960–969. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400055-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adrie C, Bachelet M, Vayssier-Taussat M, Russo-Marie F, Bouchaert I, Adib-Conquy M, Cavaillon JM, Pinsky MR, Dhainaut JF, Polla BS. Mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptosis peripheral blood monocytes in severe human sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:389–395. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2009088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koyasu S. The role of PI3K in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:313–319. doi: 10.1038/ni0403-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao Y, Hung MC. A new role of protein phosphatase 2a in adenoviral E1A protein-mediated sensitization to anticancer drug-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5938–5942. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers RJ, Monnier JM, Nick HS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha selectively induces MnSOD expression via mitochondria-to-nucleus signaling, whereas interleukin-1beta utilizes an alternative pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:20419–20427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsan MF, Clark RN, Goyert SM, White JE. Induction of TNF-alpha and MnSOD by endotoxin: role of membrane CD14 and Toll-like receptor-4. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1422–C1430. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.6.C1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White JE, Tsan MF. Differential induction of TNF-alpha and MnSOD by endotoxin: role of reactive oxygen species and NADPH oxidase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:164–169. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.2.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larosche I, Letteron P, Berson A, Fromenty B, Huang TT, Moreau R, Pessayre D, Mansouri A. Hepatic mitochondrial DNA depletion after an alcohol binge in mice: probable role of peroxynitrite and modulation by manganese superoxide dismutase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 332:886–897. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.160879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nisoli E, Clementi E, Paolucci C, Cozzi V, Tonello C, Sciorati C, Bracale R, Valerio A, Francolini M, Moncada S, Carruba MO. Mitochondrial biogenesis in mammals: the role of endogenous nitric oxide. Science. 2003;299:896–899. doi: 10.1126/science.1079368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irrcher I, Ljubicic V, Hood DA. Interactions between ROS and AMP kinase activity in the regulation of PGC-1alpha transcription in skeletal muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C116–C123. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00267.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Easton RM, Cho H, Roovers K, Shineman DW, Mizrahi M, Forman MS, Lee VM, Szabolcs M, de Jong R, Oltersdorf T, Ludwig T, Efstratiadis A, Birnbaum MJ. Role for Akt3/protein kinase Bgamma in attainment of normal brain size. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1869–1878. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1869-1878.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juntilla MM, Patil VD, Calamito M, Joshi RP, Birnbaum MJ, Koretzky GA. AKT1 and AKT2 maintain hematopoietic stem cell function by regulating reactive oxygen species. Blood. 2010;115:4030–4038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-241000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calamito M, Juntilla MM, Thomas M, Northrup DL, Rathmell J, Birnbaum MJ, Koretzky G, Allman D. Akt1 and Akt2 promote peripheral B-cell maturation and survival. Blood. 2010;115:4043–4050. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-241638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huttemann M, Lee I, Samavati L, Yu H, Doan JW. Regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation through cell signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1701–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hickson-Bick DL, Jones C, Buja LM. Stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy by lipopolysaccharide in the neonatal rat cardiomyocyte protects against programmed cell death. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stavru F, Bouillaud F, Sartori A, Ricquier D, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes transiently alters mitochondrial dynamics during infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:3612–3617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100126108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi Z, He J, Su Y, He Q, Liu J, Yu L, Al-Attas O, Hussain T, Ding S, Ji L, Qian M. Physical Exercise Regulates p53 Activity Targeting SCO2 and Increases Mitochondrial COX Biogenesis in Cardiac Muscle with Age. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carre JE, Orban JC, Re L, Felsmann K, Iffert W, Bauer M, Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA, Mayhew TM, Breen P, Stotz M, Singer M. Survival in critical illness is associated with early activation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 182:745–751. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0326OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haden DW, Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Welty-Wolf KE, Ali AS, Shitara H, Yonekawa H, Piantadosi CA. Mitochondrial biogenesis restores oxidative metabolism during Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:768–777. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-161OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao Y, Zhang F, Wang L, Zhang G, Wang Z, Chen J, Gao X. Lipopolysaccharide preconditioning enhances the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells transplantation in a rat model of acute myocardial infarction. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:74. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molnarfi N, Gruaz L, Dayer JM, Burger D. Opposite regulation of IL-1beta and secreted IL-1 receptor antagonist production by phosphatidylinositide-3 kinases in human monocytes activated by lipopolysaccharides or contact with T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:446–454. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsukamoto K, Hazeki K, Hoshi M, Nigorikawa K, Inoue N, Sasaki T, Hazeki O. Critical roles of the p110 beta subtype of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in lipopolysaccharide-induced Akt activation and negative regulation of nitrite production in RAW 264.7 cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:2054–2061. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carloni S, Girelli S, Scopa C, Buonocore G, Longini M, Balduini W. Activation of autophagy and Akt/CREB signaling play an equivalent role in the neuroprotective effect of rapamycin in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Autophagy. 6:366–377. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.3.11261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu Y, Jagannath C, Liu XD, Sharafkhaneh A, Kolodziejska KE, Eissa NT. Toll-like receptor 4 is a sensor for autophagy associated with innate immunity. Immunity. 2007;27:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robey RB, Hay N. Is Akt the "Warburg kinase"?-Akt-energy metabolism interactions and oncogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robey RB, Hay N. Mitochondrial hexokinases, novel mediators of the antiapoptotic effects of growth factors and Akt. Oncogene. 2006;25:4683–4696. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernandez-Hernando C, Ackah E, Yu J, Suarez Y, Murata T, Iwakiri Y, Prendergast J, Miao RQ, Birnbaum MJ, Sessa WC. Loss of Akt1 leads to severe atherosclerosis and occlusive coronary artery disease. Cell metabolism. 2007;6:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kissner TL, Cisney ED, Ulrich RG, Fernandez S, Saikh KU. Staphylococcal enterotoxin A induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and lethality in mice is primarily dependent on MyD88. Immunology. 2010;130:516–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loof TG, Goldmann O, Gessner A, Herwald H, Medina E. Aberrant inflammatory response to Streptococcus pyogenes in mice lacking myeloid differentiation factor 88. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:754–763. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen Y, Kawamura I, Nomura T, Tsuchiya K, Hara H, Dewamitta SR, Sakai S, Qu H, Daim S, Yamamoto T, Mitsuyama M. Toll-like receptor 2- and MyD88-dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Rac1 activation facilitates the phagocytosis of Listeria monocytogenes by murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2857–2867. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01138-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.