Abstract

Tight junctions are structures located in the apicobasal region of the cell membranes. They regulate paracel-lular solute and electrical permeability of cell layers. Additionally, they influence cellular polarity, form a paracellular fence to molecules and pathogens and divide the cell membranes to apical and lateral compartments. Tight junctions adhere to the corresponding ones of neighbouring cells and by this way also mediate attachment of the cells to one other. Molecules forming the membranous part of tight junctions include occludin, claudins, tricellulin and junctional adhesion molecules. These molecules are attached to scaffolding proteins such as ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3 through which signals are mediated to the cell interior. Expression of tight junction proteins, such as claudins, may be up- or downregulated in cancer and they are involved in EMT thus influencing tumor spread. Like in tumors of other sites, lung tumors show changes in the expression in tight junction proteins. In this review the significance of tight junctions and its proteins in lung cancer is discussed with a focus on the proteins forming the membranous part of these structures.

Keywords: Tight junction, claudin, lung, carcinoma, metastasis

Lung cancer

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Due to a decline in smoking habits the incidence of lung cancer has been declining recently in many countries [2]. Even though smoking is responsible for over 90% of the cases of lung cancer, some other etiologic factors, like expose to asbestos, radon or to heavy metals also plays some role [1]. In lung cancer treated by surgery the five year survival is approximately 10-70% depending on the stage of the tumors [2]. These figures may, however, change in the future due to the appearance of more targeted therapy options based on molecular biology [2].

Lung carcinoma is divided in two main groups; non-small cell (NSCC) and small cell carcinoma (SCC) [1]. The NSCC consists of two main histologic types, squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma [1, 2]. Due to changes in smoking habits the frequency of adenocarcinoma has increased in relation to squamous cell carcinoma so that it is now the most common histologic type of lung tumors [2]. A rarer type of NSCC is large cell carcinoma, a tumor type not expressing features of keratinisation or mucin production characteristic of squamous or adenocarcinomas, respectively [1, 2].

SCC represent an aggressive neuroendocrine tumor of the lung which is strongly associated with smoking [1, 3]. It has a dismal prognosis and patients suffering from the disease cannot be operated on due to the rapid spread of the tumor [3]. It consists of small tumor cells with round or elongated nuclei, finely dispersed chromatin and frequent mitoses and apoptotic figures [1, 3]. The tumor expresses cytokeratins and neuroendocrine markers like chromogranin and synaptophysin which is in line with the epithelial and neuroendocrine differentiation of the tumor cells [3].

Due to accumulation of data on lung cancer there is a constant need to re-evaluate the classification of lung tumors. Recently, the classification of adenocarcinomas have been changed. Previously, the so called bronchioloalveolar carcinoma was classified as a special subtype of lung adenocarcinoma with tumor cells spreading along the alveolar septa [1]. According to recent concepts, the term bronchioloalveolar carcinoma has been rejected and bronchioloalveolar growth is now called a lepidiform growth pattern [2]. A pure lepidiform growth pattern without invasion is regarded as an in situ type of growth representing a precancerous or local noninvasive cancerous growth [2]. In case of a small area of invasion (< 5mm), the tumor is called a minimally invasive adenocarcinoma [2]. Other growth patterns, such as tubular, papillary, micropapillary and solid, always represent invasive growth and adenocarcinomas are now classified according to which growth pattern predominates in the tumor [2]. Tumors may also be pneumocytic or columnar type depending on whether they derive from the alveolar pneumocytes or epithelium of the bronchi [2]. Finally, some spesific histologic types of adenocarcinoma, like enteric, colloid or fetal type are classified as separate entities [2].

There is also an increased knowledge on the molecular biologic features of lung carcinoma. In adenocarcinoma EGFR and Ras mutations are found in 10-30% of cases. EGFR mutations can be used in targeted treatment by blocking kinase activation induced by constant EGFR activation with specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors [2]. BRAF mutations in codon B600E commonly found in melanocytic lesions are found in adenocarcinomas as well as EML1-ALK translocation which both are found in 5% of the cases [2]. Mutations in RB and NF1 are found in 10% of cases and p53 mutations in 30-50% of the cases [4].

It is important to distinguish squamous cell carcinoma from adenocarcinoma since the former does not respond to EGFR antikinase treatment and patients may suffer from fatal complications [2]. Ras mutations are found in 15-30% and MET amplifications in 10% of non small cell carcinomas [5]. Some non-small cell carcinomas have PTEN mutations [5, 6]. Small cell carcinomas and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas express c-kit, and they harbor c-myc amplifications and p53 and ras mutations, and a loss of p16 and RB expression [6, 7].

Tight junctions

Tight junctions are cellular structures located at the apicobasal region of epithelial cell membranes [8]. In freeze fraction electron microscopy they can be seen to form a beltlike structure around the cell [9]. Tight junctions have several functions. They regulate the electrical and solute permeability of the paracellular space and are thus important for the fluid and electrolyte balance in the body [8]. They also have a fence function segregating the apicolateral part of the cell membrane from other regions [8]. They also contribute to the polarity of the cell [8]. Tight junctions and their permeability are important in the formation of the blood brain barrier, blood retinal barrier and blood testis barrier [4]. In this way they also form secluded areas in the body which are not reached by the immunological system [4]. Breakage of these barriers may lead to autoimmune reactions. Tight junctions can also be considered as parts of the innate immune system. They also form barriers against bacteria and viruses and prevent them from invading the subepithelial tissues [4]. On the other hand, some bacteria and viruses may use components of tight junctions as gates for the entry to deeper tissues [4].

Tight junction components

Occludin was the first molecular component discovered in tight junctions. It is a 65 kDa protein with two extracellular loops and two splice variants and was first suspected to be responsible for tight junctional formation and permeability [10]. In fact, occludin transfected in human fibroblasts induces a weak cellular adhesion and its overexpression in tight junction containing cells increases the number of paracellular strands, influences transepithelial resistance and paracellular flux of molecules between cells [11]. However, embryonic stem cells lacking occludin are able to form tight junctional structures indicating that occludin is not a substantial component required for their assembly [8]. Occludin knockout mice, however, display a number of deficiencies and diseases such as testicular atrophy, atrophic gastritis, male infertility, salivary gland dysfunction, osteoporosis and brain calcifications [12]. Occludin has several phosphorylation sites and it is the phosphorylated molecule which locates to the tight junctions [10]. Phosphorylation is induced by several mechanisms, such as protein kinases [10]. Extracellular domains of occludin attach it to the tight junction and to other tight junctions proteins and influences the tight junctional permeability to some extent. The fact that occluding null mice do not have problems related to paracellular permeability is due to the redundancy of other proteins to substitute for its loss [10, 12].

Tricellulin is a 63.6 kDa tight junctional protein mainly present in contacts between three epithelial cell membranes but it is also found in bicellular contacts but to a lesser degree [11, 13]. In bicellular junctions it decreases solute and electrical permeablility while in tricellular junctions there is no influence on electrical permeability but there is a diminished permeability for macromolecules [14]. Tricellulin mutations are associated with hearing loss but do not influence renal, respiratory or gastrointestinal tight junctions to a significant degree [12]. Knockdown of tricellulin results in derangements of tight junctional assembly and occludin influences the localization of tricellulin at tight junctions [11]. Occludin and tricellulin have structural similarities, both bind ZO1 at their structurally similar carboxyterminal domain, and they also contain a MARVEL domain like MarvelD3, yet another tight junctional protein which associates with both tricellulin and occludins [12].

The junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs) belong to an immunoglobulin superfamily. They are 36-41 kDa proteins and can be divided in three groups; JAM-A, JAM-B and JAM-C [15, 16]. All contain one transmembrane domain, an intracellular carboxyterminal part containing the PDZ domain for attachments for ZO-1, for instance, and extracellular immunoglobulin like domains [17]. JAMs are present in epithelial and endothelial cells, on leucocytes and platelets. They are able to interact with integrins influencing interactions between endothelial cells and leucocytes and transmigration of leucocytes [16-18]. JAM-A may also be present as a soluble form in serum inhibiting transmigration of blood cells from the circulation to tissues [18]. Down-regulation of JAMs increases invasion and metastatic potential of cancer cells and they are downregulated in EMT [19, 20]. They also modulate paracellular permeability and contribute to the formation of blood brain barrier or blood testis barrier [21, 22]. Some viruses, like reovirus, may use JAMs as receptors for cell invasion [17].

Claudins

Claudins are essential components of tight junctions. There are 27 types of claudins in mammals, but claudin 13 is missing from humans [23, 24]. Claudins are divided in classic and non -classic claudins which is based on their sequence similarity [23]. Classic claudins include claudins 1-10, 14, 15, 17 and 19 and non classic claudins 11-13, 16, 18 and 20-24 [23]. Claudins are responsible for the solute and electrolyte permeability of the tight junctions, consequently, their expression may vary in different epithelia [4]. They regulate the solute permeability in nephrons, for example, thus claudin expression varies in different parts of kidney tubules [25]. Similarly, there is a variation in the expression of claudins in different parts of the gut [26].

Claudins are found in epithelial, mesothelial, glial and endothelial cells [27-29]. Their molecular weight is about 20 kDa and in cell membranes they are composed of two extracellular loops, EL1 and EL2, four transmembrane domains, one small 20 amino acid long intracellular part between the two extracellular loops and the intracellular aminoterminal and carboxyterminal ends [4, 23]. In the carboxyterminal ends there are domains recognizing the PDZ domains of ZO1, ZO2 and ZO3 [4]. The larger EL1 loop influences paracellular charge selectivity and harbours the co-receptor site for hepatitis C [4]. The smaller EL2 binds the claudin molecule to the corresponding one of the neighbouring cell [4]. It also contains the oligomerisation site and receptor site for clostridium perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) [4].

Claudins associate to one and other laterally and vertically [23]. Vertical association takes place between claudins of neigbouring cells and lateral binding between claudins in the same cell [23]. The exact mechanisms of the association is not known, but claudins may form either homo-or heterodimers. However, not every claudin can associate with each other; claudins 1 and 2, for instance, cannot heterodimerize [23]. The association of claudins between neighbouring cells in tight junctions determines the paracellular permeability of cell layers [23]. Claudin 4, for instance, has a sealing function while claudin 2 generally increases the paracellular permeability [23].

Claudins and tight junctional proteins in the lung

In lung tissue, mRNA for several claudins has been detected. Claudins 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 and 18 have been detected in bronchial cells, the same claudins except for claudin 2 in type 1 alveolar and the same except for claudin 8 in type 2 alveolar cells [4]. Mesothelial cells are found to express claudins 1, 2, 3, 5 and 7 [4]. Lung endothelial cells express claudin 5 and ZO-1 [30]. In lung embryonic development bronchial epithelial cells express claudins 1, 3, 4, 5 and 7 [31]. During lung tissue maturation expression of claudin 5 decreases in bronchial epithelium [31]. In mature bronchial epithelium claudin 1 and 4 are found in the basal epithelium while claudin 4 and 5 are found in cylindrical cells [30]. Matured alveolar cells lack claudin 1 protein expression [31]. The relative expression of claudin 1 mRNA, however, increases during lung maturation in the whole lung tissue while expression of claudin 3 and 4 mRNAs are highest in the canalicular period [31]. Even though protein expression of claudin 1 and 5 cannot be detected in mature alveolar pneumocytes of the lung, cells displaying squamous or bronchial metaplasia in interstitial lung diseases express claudin 1 and 5 and also show increased expression of claudins 2, 3, 4 and 7 [32]. Claudin expression in bronchial squamous metaplasia has not, however, been studied.

Expression of claudins in cells does not necessarily indicate the presence of tight junctions in cells. The presence of occludin usually indicates a tight junctional structure [8]. Occludin is present in bronchial airway cells but may dissociate from the membranous location due to irritation caused by hydrogen peroxide [33]. Bronchial epithelium also expresses cingulin, ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3 [30, 34]. Occludin, ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3, cingulin and JAM-1 are expressed in alveolar cells [30, 35, 36].

Tight junction proteins in lung tumors and metastatic disease

Occludin, tricellulin and JAMs

In an immunohistochemical study of lung tumors occludin was present in adenocarcinomas but it was not present in squamous cell carcinomas, small or large cell carcinomas [37]. Another study on mRNA expression of occludin indicated an increased mRNA expression in adenocarcinomas and a decreased expression of mRNA in squamous cell carcinomas compared to normal lung or bronchial tissue [30]. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that tight junctions are not formed in squamous cell carcinomas even though occludin mRNA is synthesized, alternatively immunohistochemistry might fail to detect trace concentrations of occludin in a narrowed tight junctional structure. In favor of the last interpretation an ultrastructural study indicated presence of tight junctional structures in small cell carcinoma in addition to adenocarcinoma [38].

Underexpression of occludin has been shown to lead to an elevated level of progression and metastatic potential in breast, ovarian, endometrial and liver carcinoma [39-42]. Downregulation of occludin might not be the reason for the heightened metastatic potential but be due to activation of EMT and a consequent downregulation of adhesion associated proteins. In colon carcinoma cells, for instance, activation of EMT by MEK-1 lead to activation of EMT related transcription factors and downregulation of E-cadherin, occludin and ZO1 [43]. Similar observations were also seen in ovarian carcinoma [40]. In metastatic lung carcinoma, occludin expression has not been studied. In lung adenocarcinoma, overexpression of claudin 1 leads to an increase in occludin along with ZO1 indicating a less invasive phenotype [44].

There are no studies on tricellulin expression in pulmonary tumors. In hepatic fibrolamellar carcinoma tricellulin expression was diminished compared to normal liver [45]. Similarly, tricellulin was downregulated in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma [46]. Loss of tricellulin expression may be associated with development of an EMT phenotype as has been shown in gastric carcinoma [47].

JAMs have been detected in lung alveolar and bronchial cells in the basolateral membranes [48]. There are few studies on JAM expression in lung carcinoma. JAM-1 mRNA was on about the same level in squamous cell carcinoma compared to lung parenchyma but lower than in bronchial cells [40]. On the other hand, expression was higher in adenocarcinoma than in lung parenchyma but slightly lower than in bronchial cells [40]. In a study on several malignant cell lines JAM-C was found to be highly expressed in highly metastatic cell lines while JAM-A or JAM-B did not show such tendency [49]. Knockdown of JAM-C leads to a suppression of invasive and metastatic potential of the JAM-C transfected HT1080 fibrosarcoma cell line [49].

Claudins

Claudins show a diverse expression pattern and have a variable influence on tumor behavior in different types of epithelial neoplasia. In breast carcinoma, lowered claudin 1, 2 and 7 expression associates with a more aggressive breast carcinomas [50-53]. On the other hand, high claudin 4 expression was found to be associated with a worse survival and aggressive disease in breast carcinoma [54]. In gastric carcinoma, low claudin 4 expression was associated with a worse survival of the patients [55]. In colon cancer, increased claudin 2 is associated with tumor progression and tumor growth [56]. In nasopharyngeal carcinoma decreased claudin 4 and increased claudin 7 were significantly associated with metastatic disease [57]. In ovarian carcinoma high claudin 3 and 7 expression in cells of the effusion fluid predicted a poor survival [58].

In lung carcinomas claudin expression has been studied by immunohistochemistry and mRNA expression. In the study of Paschoud et al., squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas differed in their expression of claudin 1 and 5, the latter expressing claudin 5 but not claudin 1 while the former was negative for claudin 5 and positive for claudin 1 [40]. In the qRT-PCR experiments similar trends were observed.

In the study of Moldway et al., significant differences in claudin expression could be found between small cell lung carcinoma and adenocarcinoma and small cell lung carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in immunohistochemical claudin 2 expression [59]. There were also significant differences between squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, the former expressing less claudin 3, and squamous cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma with claudins 3 and 4, and between squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma with claudin 7 [59] which were in agreement with some previous studies [60, 61]. Additionally, carcinoid tumors generally showed a low expression of claudins and in this respect were different from other lung tumors [59, 61].

In the study of Moldway et al, the qRT-PCR results on tumor tissue appeared similar to those observed in immunohistochemical analyses [59]. Small cell lung carcinoma had a 16 fold higher level of claudin 3 mRNA expression than normal lung tissue, while claudin 4 mRNA was upregulated to 3-4 fold level in squamous, adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma [59]. Both adeno- and squamous cell carcinoma showed a slight downregulation of claudin 1 mRNA compared to normal lung and squamous cell carcinomas had a 2.7 fold level of claudin 1 mRNA than adenocarcinomas [59].

Chao et al. studied claudin 1 expression in adenocarcinoma and found that a low expression of claudin 1 was associated with a worse survival in these tumors both by immunohistochemistry and mRNA expression [44]. Transfection experiments in lung carcinoma cell lines changed them to less invasive and aggressive [44]. Regardless of this claudin 1 overexpressing cells were able to activate MMP2 [44]. Also claudins 2-5 have been shown to activate MMPs in some studies [62, 63].

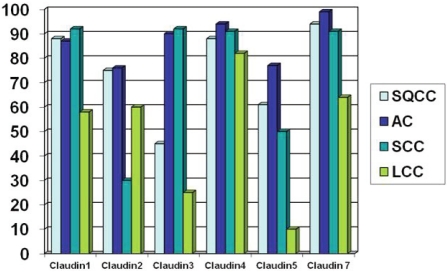

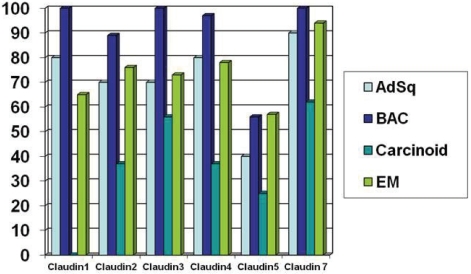

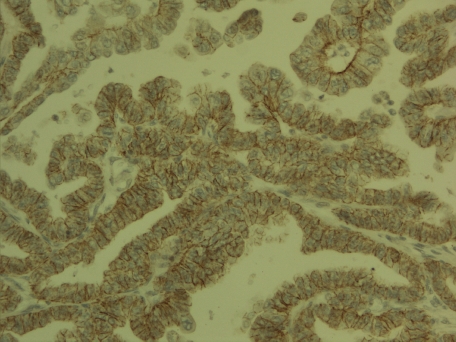

In immunohistochemical expression of claudins 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 on lung carcinomas based on our studies the three primary lung epithelial tumors (SQCC, AC and SCC) showed significantly stronger claudin 1 positivity than other types of lung tumors [60, 61] (Figure 1 and 2). Squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas (including bronchioloalveolar carcinomas) had significantly more cases with claudin 2 positivity than small cell carcinomas or carcinoid tumors. Squamous cell and large cell carcinomas showed a lower claudin 3 positivity compared to adenocarcinomas, small cell carcinomas, bronchioloalveolar carcinomas, carcinoid tumors and adenosquamous carcinomas.

Figure 1.

Percentage of cases with high immunohisto-chemical expression of claudins 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 in squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC), adenocarcinoma (AC), small cell carcinoma (SCC) and large cell carcinoma (LCC) [60, 61]. Low expression < 15%, High expression > 15%.

Figure 2.

Percentage of cases with high iImmunohistochemical expression of claudins 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 in adenosquamous carcinoma (AdSq), bronchioloal-veolar carcinoma (BAC), carcinoid tumors and pulmonary epithelial metastases (EM) [60, 61] Low expression < 15%, High expression > 15%.

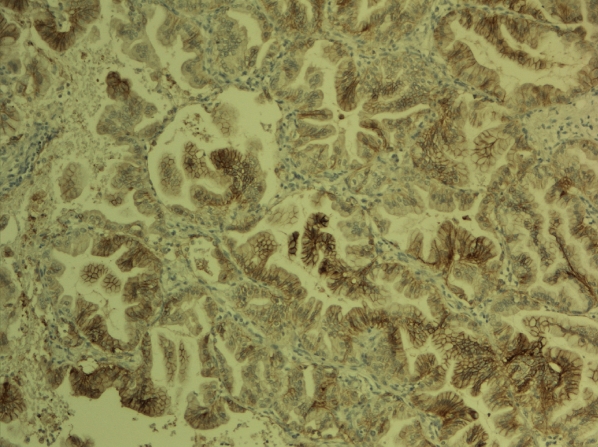

Small cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas showed a stronger claudin 4 positivity compared to squamous cell carcinomas, large cell carcinomas, carcinoid tumors, large cell carcinomas, however, showing a higher frequency of positivity compared with carcinoid tumors (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Claudin 4 expression in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Membrane bound expression is seen in most of the cells.

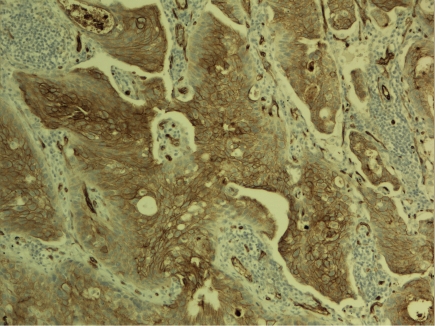

Adenocarcinomas displayed most claudin 5 positive cases, followed by squamous cell carcinomas and small cell carcinomas (Figure 4). Others tumors were mainly weak or negative in regard to claudin 5 expression. Compared to other claudins studied, claudin 5 was clearly the most weakly expressed and expression was significantly lower compared to the expression of other claudins. Interestingly also, bronchioloalveolar carcinomas had a similar expression of claudins as adenocarcinomas in general except for the fact that they had a lower expression of claudin 5. This indicates that in situ type of adenocarcinomas as bronchioloalveolar carcinomas mostly are according to a modern classification [1, 2] show a lower expression of this claudin than invasive tumors suggesting that upregulation of claudin 5 might indicate lung adenocarcinoma progression.

Figure 4.

Claudin 5 expression in pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Stronger expression is found in the central areas of the tumor cell islands.

The strongest positivity for all claudins studied, on the other hand, was for claudin 7 (Figure 5). Large cell carcinomas and carcinoid tumors had, however, a lower expression.

Figure 5.

Claudin 7 in pulmonary adenocarcinoma with a papillary growth pattern. Carcinoma cells are surrounded by a claudin 7 positive zone.

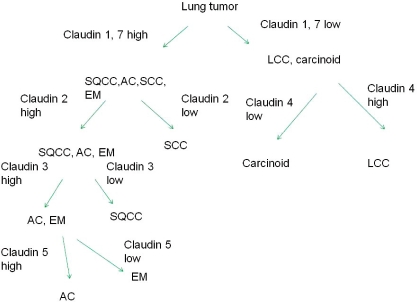

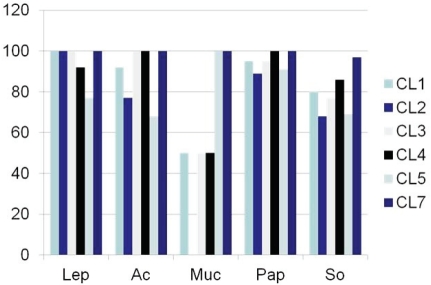

Based on these expressions, a schematic presentation displaying a differential diagnosis of lung tumors based on claudin 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 can be proposed (Figure 6). Such a presentation is, however, a crude estimation, representing only an estimation of probable immunoreactivity. Consequently, claudin expression is hardly useful in the differential diagnosis between lung tumors in surgical pathology if compared with other immunohistochemical markers. Figure 7 shows the expression of claudins 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 in lung adenocarcinoma based on growth pattern. In adenocarcinoma, the solid and mucinous type lung carcinoma shows some reduction in membrane bound positivity.

Figure 6.

Differential diagnosis of lung tumors based on claudin 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 immunoreactivity. (SQCC=squamous cell carcinoma, AC = adenocarcinoma, SCC=small cell carcinoma, LCC=large cell carcinoma, EM=Pulmonary epithelial metastases).

Figure 7.

Expression of claudins 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 in relation to adenocarcinoma growth pattern. The solid and mucinous type growth pattern shows a reduction in claudin expression. (Lep=lepidiform, Ac=acinar, Pap=papillary, Muc=mucinous, So=solid).

Claudin 18 is expressed in pulmonary tissues and in the gastrointestinal tract. Consequently, it is expressed in GI derived tumors, such as pancreatic carcinomas, gastric carcinomas and colon carcinomas, the latter, however, displaying a low frequency [64-67]. In our study on lung carcinomas, claudin 18 was especially expressed in adenocarcinomas displaying a 20% positivity and the expression was specifically found in tumors of non-smokers [68]. Claudin 10 was reminiscent in its expression to claudin 18 in this respect also being displayed in approximately 20% of cases [68]. Claudin 18 was also associated with a better prognosis [68].

Regulation of claudin expression in cancer

EMT is proposed to be detrimental in the invasive and metastatic process [69, 70]. In EMT epithelial tumor cells lose their epithelial traits, such as E-cadherin expression and display fibroblast type traits such as smooth muscle actin and vimentin [69, 70]. In EMT, downregulation of claudins, like claudin 1, has been observed [71]. EMT is regulated by transcription factors, like slug, snail, twist or zeb1 [69, 70]. In fact, claudin 1 has been shown to be downregulated by snail and slug [72].

In a study on lung tumors, epithelial metastases showed a 50- 70% expression of claudins 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 while the expression of claudin 7 was about 90% [60]. In metastases, twist and zeb1 were higher in pulmonary metastases than in primary lung tumors and there was an inverse association between zeb1 and claudins 1 and 2 and twist and claudin 5 [73]. Like in breast carcinoma, the expression of twist and zeb1 is low in lung carcinoma representing less than 15% of the cases [73]. However, EMT related transcription factors surely play a role and influence claudin expression in lung tumors.

Many cancer genes, however, also influence claudin expression and are able to modify their presence in tumor cells. Over 30% of lung cancer show EGFR overexpression and EGFR has been found to upregulate claudins 2, 3 and 4 and downregulate claudin 2 [75, 76]. Similarly K-ras which is present in lung carcinoma, upregulates claudins 1, 4 and 7 but downregulates claudin 2 [77]. Claudin 18 has been shown to be regulated by protein kinases (PKC) in pancreatic carcinoma [78]. Expression is also affected by the methylation status of the gene [78]. Similarly, other claudins may be affected by epigenetic mechanisms. In gastric cancer, hypermethylation of claudin 11 promoter region leads to downregulation of claudin 11 [79]. Also histone modification plays a role. Modification of histone proteins H3 and H4 in claudin 3 and 4 promoter regions in ovarian carcinoma leads to a repression of gene expression [80]. Epigenetic modification of claudins in lung tumors have not, however, been studied, neither is there any information on microRNA regulation of claudin gene expression in general.

In conclusion the influence of tight junctions and their proteins on lung carcinoma development and progression is complex. There are some differences in the expression of tight junctional proteins, such as claudins, in different histological types of lung tumors, but it seems not to be of great assistance in the differential diagnosis of special tumor types. During EMT the expression of tight junctional proteins would be expected to decline and even though there are some indications of this in some studies, tight junctional proteins may many times be overexpressed in lung tumors. This could be related to other effects of tight junctional proteins, such as claudins, which may activate matrix metalloproteinases and in this way promote tumor spread. Much research needs still to be done to elucidate the role of tight junctions in lung neoplasia.

References

- 1.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. Pathology & Genetics. WHO Classification of tumours: IARC Press, Lyon; 2004. Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and heart. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, Beer DG, Powell CA, Riely GJ, Van Schil PE, Garg K, Austin JH, Asamura H, Rusch VW, Hirsch FR, Scagliotti G, Mitsudomi T, Huber RM, Ishikawa Y, Jett J, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Sculier JP, Takahashi T, Tsuboi M, Vansteenkiste J, Wistubal, Yang PC, Aberle D, Brambilla C, Flieder D, Franklin W, Gazdar A, Gould M, Hasleton P, Henderson D, Johnson B, Johnson D, Kerr K, Kuriyama K, Lee JS, Miller VA, Petersen I, Roggli V, Rosell R, Saijo N, Thunnissen E, Tsao M, Yankelewitz D. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracicsociety/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary-classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628–1638. doi: 10.5858/2009-0583-RAR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soini Y. Claudins in lung diseases. Respir Res. 2011;12:70. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z, Stiegler AL, Boggon TJ, Kobayashi S, Halmos B. EGFR-mutated lung cancer: a paradigm of molecular oncology. Oncotarget. 2010;1:497–514. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin G, Kim MJ, Jeon HS, Choi JE, Kim DS, Lee EB, Cha SI, Yoon GS, Kim CH, Jung TH, Park JY. PTEN mutations and relationship to EGFR, ERBB2, KRAS, and TP53 mutations in non-small cell lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 2010;69:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Araki K, Ishii G, Yokose T, Nagai K, Funai K, Kodama K, Nishiwaki Y, Ochiai A. Frequent overexpression of the c-kit protein in large cell neuroendocrinecarcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2003;40:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawada N, Murata M, Kikuchi K, Osanai M, Tobioka H, Kojima T, Chiba H. Tight junctions and human diseases. Med Electron Microsc. 2003;36:147–156. doi: 10.1007/s00795-003-0219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godfrey RW. Human airway epithelial tight junctions. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;38:488–499. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970901)38:5<488::AID-JEMT5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function andconnections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuse M. Molecular basis of the core structure of tight junctions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raleigh DR, Marchiando AM, Zhang Y, Shen L, Sasaki H, Wang Y, Long M, Turner JR. Tight junction-associated MARVEL proteins marveld3, tricellulin, and occludin have distinct but overlapping functions. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1200–1213. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikenouchi J, Sasaki H, Tsukita S, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Loss of occludin affects tricellular localization of tricellulin. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4687–4693. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krug SM, Amasheh S, Richter JF, Milatz S, Gün-zel D, Westphal JK, Huber O, Schulzke JD, Fromm M. Tricellulin forms a barrier to macromolecules intricellular tight junctions without affecting ion permeability. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3713–3724. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham SA, Arrate MP, Rodriguez JM, Bjercke RJ, Vanderslice P, Morris AP, Brock TA. A novel protein with homology to the junctional adhesion molecule. Characterization of leukocyte interactions. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34750–34756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bazzoni G. The JAM family of junctional adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:525–530. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antar AA, Konopka JL, Campbell JA, Henry RA, Perdigoto AL, Carter BD, Pozzi A, Abel TW, Dermody TS. Junctional adhesion molecule-A is required for hematogenous dissemination of reovirus. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haarmann A, Deiss A, Prochaska J, Foerch C, Weksler B, Romero I, Couraud PO, Stoll G, Rieckmann P, Buttmann M. Evaluation of soluble junctional adhesion molecule-A as a biomarker of human brain endothelial barrier breakdown. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naik MU, Naik TU, Suckow AT, Duncan MK, Naik UP. Attenuation of junctionaladhesion molecule-A is a contributing factor for breast cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2194–2203. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naik UP, Naik MU. Putting the brakes on cancer cell migration: JAM-A restrains integrin activation. Cell Adh Migr. 2008;2:249–251. doi: 10.4161/cam.2.4.6753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeung D, Manias JL, Stewart DJ, Nag S. Decreased junctional adhesion molecule-A expression during blood-brain barrier breakdown. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:635–642. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WangY, Lui WY. Opposite effects of interleukin-1alpha and transforming growth factor-beta2 induce stage-specific regulation of junctional adhesion molecule-B gene in Sertoli cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2404–2412. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krause G, Winkler L, Mueller SL, Haseloff RF, Piontek J, Blasig IE. Structure and function of claudins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:631–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mineta K, Yamamoto Y, Yamazaki Y, Tanaka H, Tada Y, Saito K, Tamura A, Igarashi M, Endo T, Takeuchi K, Tsukita S. Predicted expansion of the claudin multigene family. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:606–612. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiuchi-Saishin Y, Gotoh S, Furuse M, Takasuga A, Tano Y, Tsukita S. Differential expression patterns of claudins, tight junction membrane proteins,in mouse nephron segments. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:875–886. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V134875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes JL, Van Itallie CM, Rasmussen JE, Anderson JM. Claudin profiling in the mouse during postnatal intestinal development and along the gastrointestinal tract reveals complex expression patterns. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soini Y. Expression of claudins 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 in various types of tumours. Histopathology. 2005;46:551–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soini Y, Kinnula V, Kahlos K, Pääkkö P. Claudins in differential diagnosis between mesothelioma and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pleura. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:250–254. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.028589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morita K, Sasaki H, Fujimoto K, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Claudin-11/OSP-based tight junctions of myelin sheaths in brain and Sertoli cells in testis. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:579–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paschoud S, Bongiovanni M, Pache JC, Citi S. Claudin-1 and claudin-5 expression patterns differentiate lung squamous cell carcinomas from adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:947–954. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaarteenaho R, Merikallio H, Lehtonen S, Harju T, Soini Y. Divergent expression of claudin -1, - 3, -4, -5 and -7 in developing human lung. Respir Res. 2010;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaarteenaho-Wiik R, Soini Y. Claudin-1, -2, -3, - 4, -5, and -7 in usualinterstitial pneumonia and sarcoidosis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:187–195. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chapman KE, Waters CM, Miller WM. Continuous exposure of airway epithelial cells to hydrogen peroxide: protection by KGF. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:71–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang Q, Wang T, Zhang H, Mohandas N, An X. A Golgi-associated protein 4.1Bvariant is required for assimilation of proteins in the membrane. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1091–1099. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang F, Daugherty B, Keise LL, Wei Z, Foley JP, Savani RC, Koval M. Heterogeneity of claudin expression by alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:62–70. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0180OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daugherty BL, Mateescu M, Patel AS, Wade K, Kimura S, Gonzales LW, Guttentag S, Ballard PL, Koval M. Developmental regulation of claudin localization by fetal alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:1266–1273. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00423.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobioka H, Tokunaga Y, Isomura H, Kokai Y, Yamaguchi J, Sawada N. Expressionof occludin, a tight-junction-associated protein, in human lung carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:472–476. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukherjee TM, Smith K, Swift JG. Scope of scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy and freeze fracture technique in diagnostic cytology of effusions. Scan Electron Microsc. 1983;(Pt3):1317–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orbán E, Szabó E, Lotz G, Kupcsulik P, Páska C, Schaff Z, Kiss A. Different expression of occludin and ZO-1 in primary and metastatic liver tumors. Pathol Oncol Res. 2008;14:299–306. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurrey NK, K A, Bapat SA. Snail and Slug are major determinants of ovarian cancer invasiveness at the transcription level. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobioka H, Isomura H, Kokai Y, Tokunaga Y, Yamaguchi J, Sawada N. Occludin expression decreases with the progression of human endo-metrial carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin TA, Mansel RE, Jiang WG. Loss of occludin leads to the progression of human breast cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2010;26:723–734. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lemieux E, Bergeron S, Durand V, Asselin C, Saucier C, Rivard N. Constitutively active MEK1 is sufficient to induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in intestinal epithelial cells and to promote tumor invasion and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1575–1586. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chao YC, Pan SH, Yang SC, Yu SL, Che TF, Lin CW, Tsai MS, Chang GC, Wu CH, Wu YY, Lee YC, Hong TM, Yang PC. Claudin-1 is a metastasis suppressor and correlates with clinical outcome in lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:123–133. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-456OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patonai A, Erdélyi-Belle B, Korompay A, Somorácz A, Straub BK, Schirmacher P, Kovalszky I, Lotz G, Kiss A, Schaff Z. Claudins and tricellulin in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2011;458:679–688. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kondoh A, Takano K, Kojima T, Ohkuni T, Kamekura R, Ogasawara N, Go M, Sawada N, Himi T. Altered expression of claudin-1, claudin-7, and tricellulin regardless of human papilloma virus infection in human tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131:861–868. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.562537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masuda R, Semba S, Mizuuchi E, Yanagihara K, Yokozaki H. Negative regulation of the tight junction protein tricellulin by snail-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric carcinoma cells. Pathobiology. 2010;77:106–113. doi: 10.1159/000278293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y, Nusrat A, Schnell FJ, Reaves TA, Walsh S, Pochet M, Parkos CA. Human junction adhesion molecule regulates tight junction resealing in epithelia. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2363–2374. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.13.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuse C, Ishida Y, Hikita T, Asai T, Oku N. Junctional adhesion molecule-C promotes metastatic potential of HT1080 human fibrosarcoma. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8276–8283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608836200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim TH, Huh JH, Lee S, Kang H, Kim GI, An HJ. Down-regulation of claudin-2 in breast carcinomas is associated with advanced disease. Histopathology. 2008;53:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morohashi S, Kusumi T, Sato F, Odagiri H, Chiba H, Yoshihara S, Hakamada K, Sasaki M, Kijima H. Decreased expression of claudin-1 correlates with recurrence status in breast cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2007;20:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tokés AM, Kulka J, Paku S, Szik A, Páska C, Novák PK, Szilák L, Kiss A, Bögi K, Schaff Z. Claudin-1, -3 and -4 proteins and mRNA expression in benign and malignant breast lesions: a research study. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:296–305. doi: 10.1186/bcr983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kominsky SL, Argani P, Korz D, Evron E, Raman V, Garrett E, Rein A, Sauter G, Kallioniemi OP, Sukumar S. Loss of the tight junction protein claudin-7 correlates with histological grade in both ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Oncogene. 2003;22:2021–2033. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lanigan F, McKiernan E, Brennan DJ, Hegarty S, Millikan RC, McBryan J, Jirstrom K, Landberg G, Martin F, Duffy MJ, Gallagher WM. Increased claudin-4 expression is associated with poor prognosis and high tumour grade in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2088–2097. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohtani S, Terashima M, Satoh J, Soeta N, Saze Z, Kashimura S, Ohsuka F, Hoshino Y, Kogure M, Gotoh M. Expression of tight-junction-associated proteins in human gastric cancer: downregulation of claudin-4 correlates with tumor aggressiveness and survival. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s10120-008-0497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dhawan P, Ahmad R, Chaturvedi R, Smith JJ, Midha R, Mittal MK, Krishnan M, Chen X, Eschrich S, Yeatman TJ, Harris RC, Washington MK, Wilson KT, Beauchamp RD, Singh AB. Claudin-2 expression increases tumorigenicity of colon cancer cells: role of epidermal growth factor receptor activation. Oncogene. 2011;30:3234–3247. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsueh C, Chang YS, Tseng NM, Liao CT, Hsueh S, Chang JH, Wu IC, Chang KP. Expression pattern and prognostic significance of claudins 1, 4, and 7 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:944–950. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kleinberg L, Holth A, Trope CG, Reich R, Davidson B. Claudin upregulation in ovarian carcinoma effusions is associated with poor survival. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moldvay J, Jäckel M, Páska C, Soltész I, Schaff Z, Kiss A. Distinct claudin expression profile in histologic subtypes of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sormunen R, Pääkkö P, Kaarteenaho-Wiik R, Soini Y. Differential expression of adhesion molecules in lung tumours. Histopathology. 2007;50:282–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merikallio H, Kaarteenaho R, Pääkkö P, Lehtonen S, Hirvikoski P, Mäkitaro R, Harju T, Soini Y. Impact of smoking on the expression of claudins in lung carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2010;47:620–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takehara M, Nishimura T, Mima S, Hoshino T, Mizushima T. Effect of claudin expression on paracellular permeability, migration and invasion of colonic cancer cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:825–831. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyamori H, Takino T, Kobayashi Y, Tokai H, Itoh Y, Seiki M, Sato H. Claudin promotes activation of pro-matrix metalloproteinase-2 mediated by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28204–28211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsuda Y, Semba S, Ueda J, Fuku T, Hasuo T, Chiba H, Sawada N, Kuroda Y, Yokozaki H. Gastric and intestinal claudin expression at the invasive front of gastric carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1014–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matsuda M, Sentani K, Noguchi T, Hinoi T, Okajima M, Matsusaki K, Sakamoto N, Anami K, Naito Y, Oue N, Yasui W. Immunohistochemical analysis of colorectalcancer with gastric phenotype: claudin-18 is associated with poor prognosis. Pathol Int. 2010;60:673–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sahin U, Koslowski M, Dhaene K, Usener D, Brandenburg G, Seitz G, Huber C, Türeci O. Claudin-18 splice variant 2 is a pan-cancer target suitable for therapeutic antibody development. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7624–7634. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karanjawala ZE, Illei PB, Ashfaq R, Infante JR, Murphy K, Pandey A, Schulick R, Winter J, Sharma R, Maitra A, Goggins M, Hruban RH. New markers of pancreatic cancer identified through differential gene expression analyses: claudin 18 and annexin A8. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:188–196. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31815701f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Merikallio H, Pääkkö P, Harju T, Soini Y. Claudins 10 and 18 are predominantly expressed in lung adenocarcinomas and in tumours of non-smokers. IJCEP. 2011;4:667–673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schmalhofer O, Brabletz S, Brabletz T. E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and zeb1 in malignant progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:151–166. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9179-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.De Wever O, Pauwels P, De Craene B, Sabbah M, Emami S, Redeuilh G, Gespach C, Bracke M, Berx G. Molecular and pathological signatures of epithelialmesenchymal transitions at the cancer invasion front. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:481–494. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kojima T, Takano K, Yamamoto T, Murata M, Son S, Imamura M, Yamaguchi H, Osanai M, Chiba H, Himi T, Sawada N. Transforming growth factor-beta induces epithelial to mesen-chymal transition by down-regulation of claudin-1 expression and the fence function in adult rat hepatocytes. Liver Int. 2008;28:534–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martínez-Estrada OM, Cullerés A, Soriano FX, Peinado H, Bolós V, Martínez FO, Reina M, Cano A, Fabre M, Vilaró S. The transcription factors Slug and Snail act as repressors of Claudin-1 expression in epithelial cells. Biochem J. 2006;394:449–457. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Merikallio H, Kaarteenaho R, Pääkkö P, Lehto-nen S, Hirvikoski P, Mäkitaro R, Harju T, Soini Y. Zeb1 and twist are more commonly expressed in metastatic than primary lung tumours and show inverse associations with claudins. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:136–140. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soini Y, Tuhkanen H, Sironen R, Virtanen I, Kataja V, Auvinen P, Mannermaa A, Kosma VM. Transcription factors zeb1, twist and snai1 in breast carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang Z, Stiegler AL, Boggon TJ, Kobayashi S, Halmos B. EGFR-mutated lung cancer: a paradigm of molecular oncology. Oncotarget. 2010;1:497–514. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh AB, Harris RC. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation differentially regulates claudin expression and enhances transepithelial resistance in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3543–3552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mullin JM, Leatherman JM, Valenzano MC, Huerta ER, Verrechio J, Smith DM, Snetselaar K, Liu M, Francis MK, Sell C. Ras mutation impairs epithelial barrier function to a wide range of nonelectrolytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5538–5550. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ito T, Kojima T, Yamaguchi H, Kyuno D, Kimura Y, Imamura M, Takasawa A, Murata M, Tanaka S, Hirata K, Sawada N. Transcriptional regulation of claudin-18 via specific protein kinase C signaling pathways and modification of DNA methylation in human pancreatic cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1761–1772. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Agarwal R, Mori Y, Cheng Y, Jin Z, Olaru AV, Hamilton JP, David S, Selaru FM, Yang J, Abraham JM, Montgomery E, Morin PJ, Meltzer SJ. Silencing of claudin-11 is associated with increased invasiveness of gastric cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kwon MJ, Kim SS, Choi YL, Jung HS, Balch C, Kim SH, Song YS, Marquez VE, Nephew KP, Shin YK. Derepression of CLDN3 and CLDN4 during ovarian tumorigenesis is associated with loss of repressive histone modifications. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:974–983. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]