Abstract

Laterality (left-right ear differences) of auditory processing was assessed using basic auditory skills: 1) gap detection 2) frequency discrimination and 3) intensity discrimination. Stimuli included tones (500, 1000 and 4000 Hz) and wide-band noise presented monaurally to each ear of typical adult listeners. The hypothesis tested was: processing of tonal stimuli would be enhanced by left ear (LE) stimulation and noise by right ear (RE) presentations. To investigate the limits of laterality by 1) spectral width, a narrow band noise (NBN) of 450 Hz bandwidth was evaluated using intensity discrimination and 2) stimulus duration, 200, 500 and 1000 ms duration tones were evaluated using frequency discrimination.

Results

A left ear advantage (LEA) was demonstrated with tonal stimuli in all experiments but an expected REA for noise stimuli was not found. The NBN stimulus demonstrated no LEA and was characterized as a noise. No change in laterality was found with changes in stimulus durations. The LEA for tonal stimuli is felt to be due to more direct connections between the left ear and the right auditory cortex which has been shown to be primary for spectral analysis and tonal processing. The lack of a REA for noise stimuli is unexplained. Sex differences in laterality for noise stimuli were noted but were not statistically significant. This study did establish a subtle but clear pattern of LEA for processing of tonal stimuli.

Keywords: Auditory Perception, Lateral asymmetry, gap detection, frequency discrimination, intensity discrimination

It is well known that processing of human speech is primarily a function of the auditory areas of the left hemisphere of the brain and, while less well established, that processing of tonal or melodic stimuli is more readily accomplished by the right hemisphere. There is substantial evidence that the temporal/spectral acoustic properties of the stimulus, rather than the linguistic properties dictate the lateralization of processing (Zatorre & Belin, 2001; Schonwiesner, Rubsamen, & von Cramon, 2005). Among the acoustic qualities that distinguish speech from tonal stimuli are the rapid transitions that occur in speech. In general, auditory stimuli that are broad-band, rapidly-changing or temporally complex, including speech and noise signals, are preferentially processed in auditory areas of the left hemisphere while slowly changing or steady state, narrow-band or tonal stimuli, including music, are primarily processed in the right hemisphere (Tervaniemi & Hugdahl, 2003; Zatorre, Belin, & Penhune, 2002; Tervaniemi & Hugdahl, 2003; Zatorre et al., 2002). It is not clear, however, what the boundaries of these acoustic distinctions are and how they may affect lateralization. For example, it is not known how rapid must transitions be or how complex or smooth must the temporal structure of acoustic stimulus be to characterize any stimulus as being lateralized to one side or the other.

The distinguished structure of auditory areas in left and right temporal lobes helps to explain their specialized function. For example, the left hemisphere demonstrates shorter axonal conduction times than the right, which would aid in specialized analysis of rapid transitions (Miller, 1996). Differences in the cytoarchitecture of the left and right temporal lobes has also been noted with the left showing larger pyramidal cells, wider columns and denser afferent innervation (Hutsler, 2003). The left planum temporale is generally larger than the right (Geschwind & Levitsky, 1968; Geschwind & Levitsky, 1968), especially in males (Good et al., 2001) and the axons of the left planum are more heavily myelinated than those on right (Anderson, Southern, & Powers, 1999). Given the need for real-time processing of the variety of complex features of acoustic stimuli, it is reasonable to have simultaneous parallel processing strategies for spectral qualities and temporal features in the two hemispheres (Zatorre et al., 2002).

Ear Asymmetry

In many sensory and motor pathways, the primary route from the periphery to the brain is crossed, and this includes the auditory system (Moore, 1987). While ipsilateral, ear to brain pathways exist, performance on tasks involving auditory stimuli presented to the right ear primarily reflects processing in the left hemisphere and vice versa, due to the strong crossed pathways between the ear and the auditory cortex. Kimura and colleagues demonstrated a subtle right ear advantage (REA) for speech perception and a left ear advantage (LEA) for tonal stimuli (Kimura, 1961; Kimura, 1963; Kimura, 1964; King & Kimura, 1972; Kimura, 1973; Kimura, 1963; Kimura, 1964; King & Kimura, 1972; Kimura, 1973). More recent studies have also shown that performance can vary with the ear of presentation (Sidtis, 1980; Kallman & Corballis, 1975; Kallman, 1977; Sidtis, 1982; Kallman & Corballis, 1975; Kallman, 1977; Sidtis, 1982). These studies primarily used dichotic presentation modes and used speech and music as stimuli. Processing differences by ear in these studies are felt to reflect differences in cortical processing enhanced by the strong contra-lateral ear to brain connections rather than any differences in capacity by peripheral auditory system.

In addition, however, subtle but consistent evidence exists of differences in performance by ear in some physiologic measures of auditory peripheral function at the level of the ear and brainstem. It should be noted, however, that due to extensive corticofugal influences in the auditory system, the source of such asymmetries in humans is difficult or impossible to discern. Regardless of whether laterality of function is due to peripheral or central influences, it is important to understand the nature of subtle ear differences. For example, audiometric hearing thresholds in adults are slightly better in the right ear than the left but this finding is generally confined to males; hearing sensitivity in females is known to be more symmetric (Kannan & Lipscomb, 1974; Pirila, Jounio-Ervasti, & Sorri, 1992). Better hearing in the right ear of adults may be related to another asymmetry, the fact that the left ear is more susceptible to noise-induced hearing loss (Chung, Mason, Gannon, & Willson, 1983; Pirila, 1991). Tinnitus (ringing in the ear) occurs more often in the right ears than the left, even when hearing loss is taken into consideration (Cahani, Paul, & Shahar, 1984).

The otoacoustic emission (OAE) is a measure involving cochlear outer hair cells which, when stimulated by acoustic energy, respond by amplifying the energy thus increasing the sensitivity of the ear. The energy generated by the amplification process can be measured in the ear canal with a sensitive microphone. In general, when OAEs are elicited by transient stimuli such as clicks, the amplitude is larger in right ears than in left (Bilger, Matthies, Hammel, & Demorest, 1990; Burns, Arehart, & Campbell, 1991; Newmark, Merlob, Bresloff, Olsha, & Attias, 1997; Ismail & Thornton, 2003; Driscoll, Kei, & McPherson, 2002; Burns et al., 1991; Newmark et al., 1997; Ismail & Thornton, 2003; Driscoll et al., 2002). Sininger & Cone-Wesson (2004) have also demonstrated that newborns show larger click-evoked OAEs in the right ear and larger tone-evoked OAEs in the left ear. A small but consistent right ear advantage has also been shown for the auditory brainstem response when it is elicited by click stimuli (Levine & McGaffigan, 1983; Eldredge & Salamy, 1996; Sininger & Cone-Wesson, 2006).

With the possible exception of speech perception, however, there is a tendency for auditory scientists to assume that the left and right ears are physiologically and functionally equal. Psychoacoustic experiments are often carried out in one ear only and very rarely is the performance of the two ears compared in these studies. Consequently, there have been few studies contrasting basic auditory capacity in the two ears. Given that the left auditory cortex is specialized for the processing of temporally complex stimuli (speech or noise) and the right for simple spectral processing (tonal stimuli) these same distinctions may be evident in performance on psychoacoustic tasks in the ears contralateral to the preferred brain side, likely due to top-down influence. That is, performance on tasks using tonal stimuli should be better when the stimuli are presented to the left ear while performance using complex stimuli such as noise should show the best performance when presented to the right ear.

Laterality of auditory function has been studied using a basic gap detection task. In this paradigm subjects are asked to detect a short duration silent gap within an acoustic stimulus (marker) which flanks the silent period. The threshold of the duration of the perceptible gap is determined. In the best situations a gap of ~3 ms may be discernible in listeners with normal hearing. Two studies found a REA for gap detection in a broad band noise marker (Sulakhe, Elias, & Lejbak, 2003; Brown & Nicholls, 1997; Brown & Nicholls, 1997). Sininger & de Bode (2008) used both tonal and broad-band noise markers to compare gap detection thresholds (GDTs) across ears in typical adult listeners. They demonstrated a REA for gap detection when noise markers were used and a LEA when tonal markers were used. However, using paradigms nearly identical to Sininger & deBode, neither Baker, Jayewardene, Sayle, & Saeed (2008) nor Grose (2008) found asymmetry in gap detection using a broad-band noise marker. Clearly, lateralized auditory function is elusive and careful control of studies may be needed to determine which subject and stimulus factors may be influencing outcomes of these experiments.

Does the stimulus or the function drive laterality?

The basic auditory processing capacity of the two hemispheres, discussed above, would indicate that each side may be optimized for various tasks. For example, processing of rapid temporal changes in the auditory signal would be processed best by the left hemisphere and show a REA while frequency analysis would be best performed by the right hemisphere and show a LEA. Brancucci, and colleagues found that ear preferences change with task and not with stimulus using both speech and music stimuli (Brancucci, Babiloni, Rossini, & Romani, 2005; Brancucci, D’Anselmo, Martello, & Tommasi, 2008). In contrast, Sininger & de Bode (2008) studied gap detection which would generally be assumed to be a left hemisphere function showing a REA and found that ear advantage for GDT changed with the acoustic properties of stimulus. They concluded that the stimulus itself, and not the task, dictated laterality. This issue is unresolved.

Other factors influencing laterality

Lateralized function is most clear when the subject’s attention is focused on the processing task. Generally, attention is focused by the task itself, such as asking the subject to discriminate stimuli along the dimension of interest. For example, lateralized processing for speech in the left hemisphere and music on the right as measured by PET was found only when an oddball discrimination task was employed but this lateralization was not seen with the standard or deviant stimuli alone (Tervaniemi et al., 2000). Zatorre, Evans, Meyer & Gjedde (1992) point out that increased activation of brain regions on one side with attention to a task, is due, at least in part, to the recruitment of association areas in the same hemisphere.

Both the sex and the handedness of the listener can influence laterality. Male participants show more asymmetry in performance of tasks related to language and speech processing than their female counterparts (McGlone, 1980; Shaywitz et al., 1995; Brown, Fitch, & Tallal, 1999; McGlone, 1980; Jones & Byrne, 1998). In addition, left handed subjects are more likely to show opposite patterns of laterality, especially right hemisphere dominance for language/speech processing (Knecht et al., 2000; Jones & Byrne, 1998).

Critical Stimulus Duration

Analysis of any spectral information requires adequate stimulus duration to resolve components and the laterality of processing could be dependent upon stimulus duration. For example, laterality was evaluated in two separate studies using an auditory evoked potential paradigm termed the Auditory Steady State Response or ASSR. In one study, the ASSR in response to tonal stimuli was lateralized to the right hemisphere using stimulus presentations of between 600 ms and 2 s in duration (Ross, Herdman, & Pantev, 2005). The second study utilized tonal stimuli that were significantly shorter in duration (12 ms) and found the activity was localized to the left hemisphere (Yamasaki et al., 2005).

It is reasonable to assume that right hemisphere spectral processing requires sufficient stimulus duration but the exact durations are not clear. Using PET, Belin, Zilbovicius, Crozier, Thivard & Fontaine (Belin, Zilbovicius, Crozier, Thivard, & Fontaine, 1998) determined that speech with fast transitions (40 ms) was processed in the left hemisphere and speech with slow transitions (200 ms) was bilaterally processed. It may be that durations of 200 ms are still insufficient to allow ample processing time in the right hemisphere. The critical duration, if such exists, for right hemisphere spectral processing is unknown.

Purpose

The purpose of the study which follows was to determine the extent to which auditory function is lateralized and explore the influence of stimulus parameters on laterality. All experiments were conducted with monaural stimuli presented to the left and right ears randomly. Three basic auditory functions were used to assess laterality including frequency discrimination, intensity discrimination and GDTs. Evaluating three different tasks, with two categories of stimuli will aid in answering the question of whether the task or the stimulus type will drive laterality. We have found stimulus type to be a more salient cue for laterality than task, at least for gap detection (Sininger & de Bode, 2008) and therefore hypothesize as follows: laterality of auditory processing will be a function of spectro-temporal nature of the stimulus. Performance was compared by ear of presentation. Simple tonal stimuli should be preferentially processed by the right hemisphere and left ear while temporally complex, wide-band noise stimuli should be optimally processed in the left hemisphere when presented to the right ear. Further, the boundaries of spectro- temporal complexity that influence laterality will be explored by varying the bandwidth and the duration of the stimuli and determining the influence of these factors on laterality.

METHODS

Listeners

Thirty- four adult participants were enrolled in this study, 17 each males and females, ranging in age from 18 to 32 years with a mean of 23.88 years. All subjects were right handed as measured by the Edinburgh Laterality Scale (Oldfield, 1971). In the scoring convention, +100 is completely right handed and −100 is completely left handed. The mean handedness score of participants was 97.16 with a range of 71–100. The average years of formal education of the subjects was 15.69 with a range of 12–22 years. Tervaniemi & Hugdahl (2003) point out the importance of controlling for language and music training in laterality experiments of this type. Musical experience in terms of years of formal training was documented by questionnaire. The subjects ranged from 0 to 11 years of formal music education with a mean of 2.17 years. All participants had normally appearing tympanic membranes and un-occluded ear canals on otoscopic examination and demonstrated normal middle ear function by tympanometry, with middle ear pressure ranging from −15 to +65 daPa and compliance ranging from 0.3 to 2.1 ml. Air conducted hearing thresholds were measured on a standard clinical audiometer (Interacoustics AC-40) at octave frequencies from 500 to 8000 Hz. The mean average threshold for both ears was 2.35 dB HL with a range of −2 to 13 dB. No individual threshold was greater than 25 dB at 500 Hz nor greater than 20 dB at all other frequencies. In addition, all listeners demonstrated normal cochlear function based on a distortion-product otoacoustic emission test (Biologic Scout). DPOAES exceeded noise floor levels by 6 dB or more for 3 of 5 frequencies between 1500 and 8000 Hz for each ear of all listeners.

Psychophysics

Experiments were designed to evaluate a) frequency discrimination, b) intensity discrimination and c) temporal gap detection thresholds (GDTs). Where possible, both broad-band noise and tonal stimuli were employed in these measures. In addition, within these paradigms, stimuli were chosen to evaluate laterality based on stimulus bandwidth and duration. For each experiment, a three alternative forced choice (3-AFCT) paradigm was employed. Stimuli were generated and presented and experiments were controlled using a TDT System-II and SykofizX software (Tucker-David Technologies, Gainesville, FL). Three token stimuli were presented for each trial with one of the three, in random order, varying on the experimental parameter. The inter-stimulus interval were 500 ms in length. The stimulus presentations corresponded to lights on a response box. The subject was instructed to listen to all three, watching the indicator lights and then to indicate which of the three stimuli differed from the standard by pressing the corresponding button. Feedback on the correct choice was provided immediately as the light corresponding to the correct choice button was illuminated.

The magnitude of the parameter under test was controlled by the subject’s response. After two correct responses, the parameter decreased by a factor of 1.5 for two reversals followed by a factor of 1.1 for the remainder of the experiment. One incorrect response triggered an increase in the parameter. The experimental condition was concluded when six reversals occurred on small step sizes. The result was the average of the final eight parameter values. Initial parameter values were as follows: +10 dB for intensity, 50 ms for gap duration and +50 Hz for frequency change with the exception of the 4000 Hz stimulus which began with +200 Hz frequency change.

Subject factors that were expected to influence laterality were carefully controlled. Handedness and gender were controlled as described above. In order to perform the discrimination task, the subjects’ attention was necessarily focused on the task. No further direction of attention was used.

Stimuli

All stimuli were generated by a 16-bit D/A converter with a 44,000 Hz sampling rate and presented to each ear individually via Etymotic ER-3 insert earphones coupled to the ear with foam ear tips. Standard stimuli were broad-band white noise (20–14,000 Hz) and pure tones of 500, 1000 and 4000 Hz with random starting phase. Stimuli were typically 1000 ms in duration with a 10 ms cosign taper at onset and offset. All stimuli were calibrated to 50 dB SPL in a 2-cm3 coupler with a Bruel and Kjaer, model 2235 sound level meter. In addition, following general calibration, the levels of the right and left earphones were equalized by comparing the digitized outputs on an oscilloscope for amplitude and fine tuning the earphone output. In this way we could assure that the output of the left and right earphones differed by less than one dB for all stimuli.

Duration of the stimuli was manipulated during the frequency discrimination experiments and bandwidth was manipulated during the intensity discrimination experiments as shown below.

In addition to evaluating laterality of frequency, intensity and temporal resolution, the experiments were designed to evaluate the effect of overall duration and stimulus bandwidth on the laterality of the response. This was accomplished by varying the duration of the tones used for frequency discrimination using 200, 500 and 1000 ms durations and by using three bandwidths of stimuli for the intensity discrimination. Two bandwidths, tonal and narrow band were used for 1000 Hz stimuli as well as broad band noise. The narrow-band noise spectrum, measured through the ER3A was centered at 1104 Hz with 6 dB down points at 864 Hz and 1310 Hz (approximately 450 Hz bandwidth). The broad-band noise was driven with a digital signal of 20–14,000 Hz which produced an acoustic signal through the ER-3A with flat spectrum from 100 to 4000 Hz with approximately 6 dB/octave roll off above 4000 Hz. All spectral measurements were performed in a 2cm3 coupler connected to a Bruel & Kjaer model 2235 sound level meter and evaluated by a Hewlett Packard Model 35660A Dynamic Signal Analyzer..

For the gap detection experiments markers were either broad-band noise or tones. Silent gaps were placed in the center of the 1000 ms marker with a 5 ms linear taper used at the leading and trailing edge of the gap to avoid spectral splatter. For tonal markers, the phase at the trailing edge of the gap preserved the phase as if no gap had occurred. The gap duration was determined as the time from the end of the 5 ms ramp at the leading edge of the gap to the start of the ramp at the trailing edge.

Procedure

All testing took place in a single walled, sound attenuating booth. Following consent procedures, listeners were screened for normal ear functions using otoscopy, tympanometry, otoacoustic emissions and standard audiometry. Listeners were instructed on the use of response box, told to indicate the one stimulus in three that differed from the others. They were told that the distinctions would be easy to detect at first, eventually would be very difficult and were instructed to guess when unsure. A trial run of one condition was used as training before each experiment. No further training was provided. Subjects were instructed to stop the procedure and ask for instructions as necessary. All experimental conditions were randomized including the order of the three experiments (frequency, intensity and gap), and the stimuli within each experiment. The stimulus manipulations and ear of presentation were also randomized prior to each subject. The entire experimental procedure was performed in one or two sessions and lasted approximately three hours including frequent breaks between experiments.

RESULTS

Gap Detection

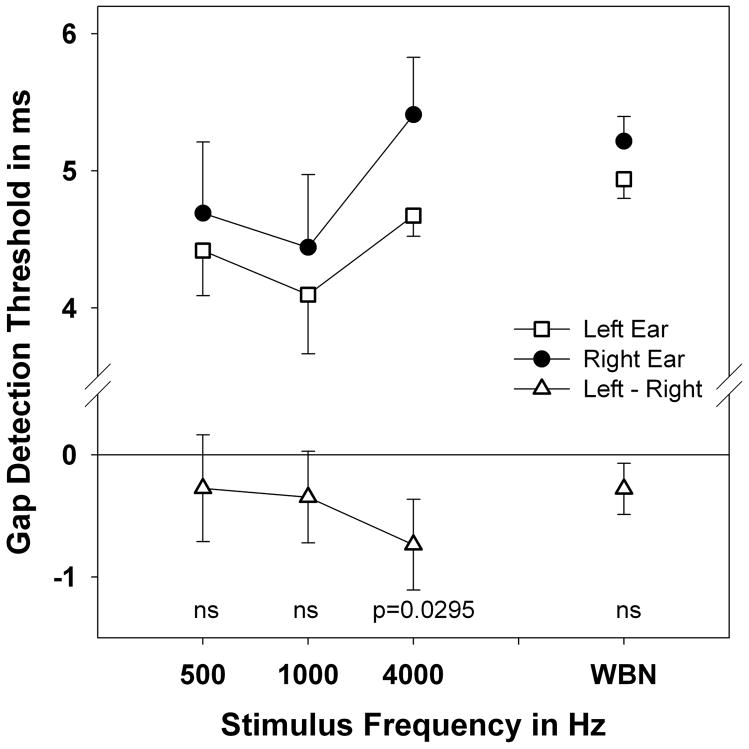

Results of GDTs in the left and right ear and difference values are plotted in Figure 1. Data is grouped by stimulus type, tones and broad-band noise. Thresholds in the left and right ear were compared by paired t-test. Mean GDT for the left ear using tones is 4.40 ms and in the right is 4.86 ms. The difference is 0.455 ms and this difference is significant (t=2.007, df=89, p=0.0239). However, among the tones, only the 4000 Hz condition reached significance (t=1.962, df=30, p=0.0295). Using noise stimuli the threshold for the right ear is 5.22 and the left threshold is 4.93ms with a difference of 0.28 but the difference is non-significant (t=1.3243, df=28, p=0.0980). Lower thresholds are indicative of superior temporal resolution. A LEA and laterality is demonstrated for tonal stimuli while no laterality is noted for noise stimuli.

Figure 1.

Mean GDTs by stimulus for left and right ears and difference scores. Error bars indicate standard error. Significance of left-right differences on paired t-test is indicated at bottom. NS= p>0.05.

Frequency Discrimination

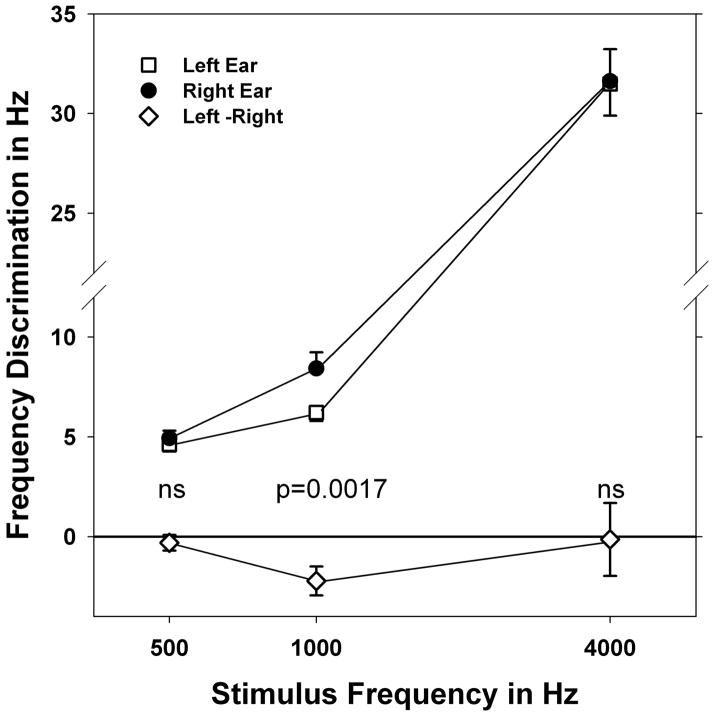

Figure 2 displays the results of frequency discrimination ability in Hz for standard duration (1000 ms) stimuli. This experiment utilized tonal stimuli exclusively. While the mean frequency discrimination ability was superior in the left ear for all three tones, ear difference (laterality) was significant only for the 1000 Hz stimulus (t=3.0249, df=64, p=0.0017).

Figure 2.

Mean frequency discrimination scores in Hz for left and right ears and difference scores. Error bars indicate standard error. Significance of left-right differences on paired t-test is indicated at bottom. NS= p>0.05.

Stimulus Duration

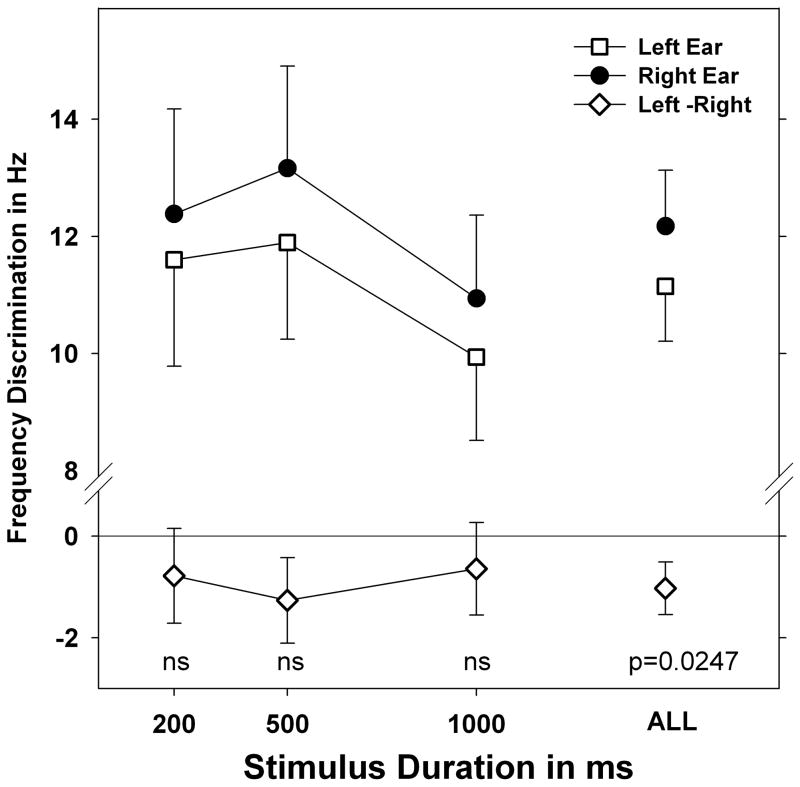

The effect of stimulus duration on laterality was tested within the frequency discrimination paradigm. The results of this experiment can be seen in Figure 3. All frequencies are collapsed by duration and plotted by mean ear score. The left-right difference scores are also plotted. For each duration the left ear shows better performance although none of these L-R differences are significant (paired t-test p values range from 0.06 to 0.20). It is clear from the Figure 2 that laterality did not change with the durations employed. This was confirmed by repeated measures ANOVA (Table 2) for Left-Right differences which found no effect of duration or interaction of duration and frequency (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Mean frequency discrimination in Hz for 3 tonal stimuli (500, 1000 and 4000 Hz) collapsed, showing the effect of stimulus duration only. Error bars indicate standard error. In all cases a slight left laterality for performance was seen and is indicated by negative left-right threshold values at bottom. Individual left-right difference scores were not significant (ns=p>0.05) but the overall difference, collapsed across duration, shows a significant laterality on paired t-test. Laterality did not change with stimulus duration which was confirmed by repeated measures ANOVA (see text).

Table 2.

ANOVA for Frequency Discrimination effects of stimulus frequency and duration.

| Source | DF | Ratio | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 2 | 2.6188 | 0.0766 |

| Duration | 2 | 0.5750 | 0.5641 |

| Duration*Frequency | 4 | 0.6298 | 0.6421 |

Intensity Discrimination

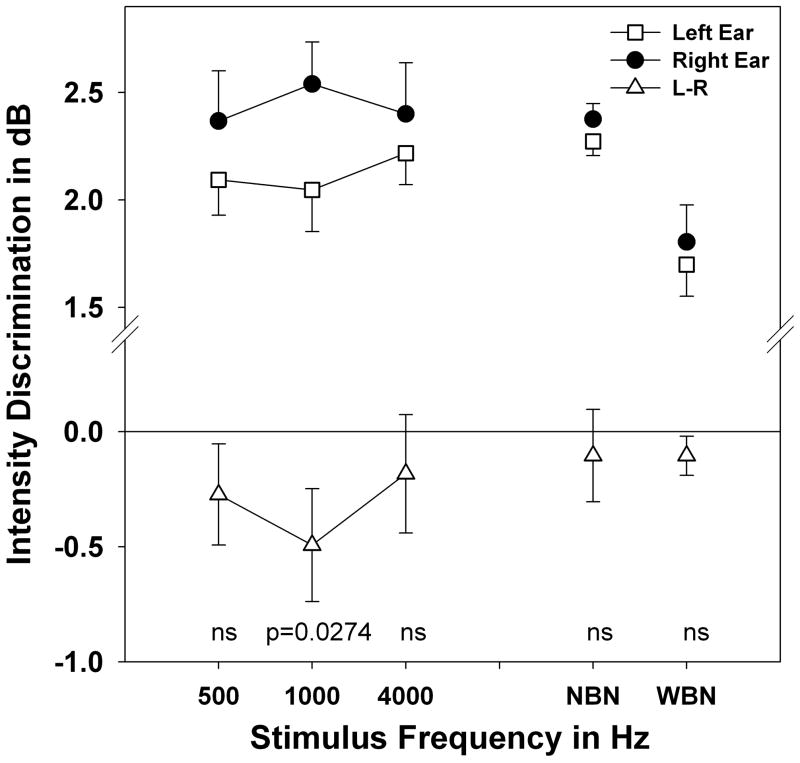

Intensity discrimination ability was evaluated with tonal and noise stimuli. Mean thresholds for discrimination in dB for each stimulus by ear and difference scores are plotted on Figure 4. Mean thresholds in the left ear are lower than those in the right ear for all stimuli. Taken as a group, the leftward laterality (left-right differences) for tonal thresholds is significant by paired t-test (t=2.303, df=81, p=0.0119). However, only 1000 Hz shows a significant ear difference (t= 2.020, df=26, p=0.0274) when each frequency is evaluated independently. Laterality for wide-band noise is non-significant (t=0.525 df=27, p=0.3016).

Figure 4.

Mean intensity discrimination in dB plotted for pure tone stimuli at left and for narrow-band and wide-band noise at the right by ear of stimulation. Error bars indicate standard error. Collapsed scores for tones in the left ear are significantly better than the right (p=0.0119) but laterality for narrow-band and wide-band noise is non-significant (ns=p>0.05).

Bandwidth

The intensity discrimination paradigm was also used to evaluate the effect of stimulus bandwidth on laterality. In addition to pure tones and wideband noise, one interim bandwidth, a narrow band of noise centered at 1000 Hz was used to explore the effect of bandwidth. Results of laterality for intensity discrimination for narrow-band noise is also plotted on Figure 4. Left right differences are not significant for this stimulus (t=1.224, df=247, p= 0.1110) demonstrating that this narrow band noise is processed in the same manner as a broad band noise.

Other Contributing Factors

Listener Sex

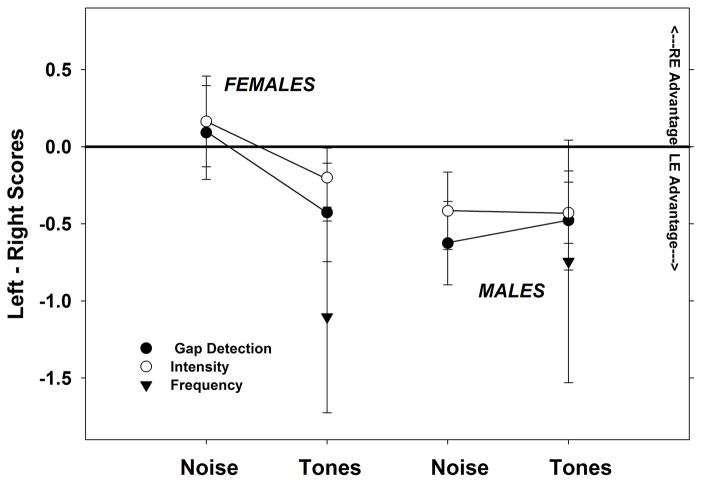

An equal number of male and female listeners was employed in each experiment to balance for the possibility that sex can influence laterality. Each experiment (gap detection, intensity and frequency discrimination) was analyzed for contribution of sex by stimulus type. Repeated measures ANOVAs were performed for factors of sex and stimulus type and interactions for each of the experiments. In no case was sex found to have a significant effect or interaction with stimulus type (tones and noise). However, a plot of the laterality (left-right scores) by stimulus type for males and females, shown in Figure 5 shows that females have a slight but non-significant REA for noise stimuli for intensity (t=0.5580, df=14, p=0.2928) and for gap detection (t=−1.486, df=49, p=0.0715).

Figure 5.

Laterality as indicated by mean left-right ear scores plotted for female subjects (left) and males (right). Data for all three experiments is shown collapsed in each by stimulus type (tones v. noise). Female subjects show a pattern of REA for noise stimuli and LEA for processing of tonal stimuli although the REA is non-significant. In contrast, males show a consistent LEA regardless of stimulus type. Error bars indicate standard error.

Music Training

Formal music training has been shown to improve some auditory skills, particularly frequency discrimination, but the effect of music training on the laterality of processing has not been examined. The years of formal music training ranged from 0 to 11 years. Three categories of music training were formulated with category A (no training) containing 15 members, category B (1–3 years) including 14 members and those with more than 7 years of formal training in Category C including 5 members. A Kruskal-Wallis test of rank sums was used to test whether performance changed with music training category. This was applied to results from left and right ears and difference scores and, where appropriate, to results with noise and tones. Frequency discrimination scores for both the left (χ2 =6.76, df=2, p= 0.0340) and right ears (χ2 =9,19, df=2, p= 0.0101) were shown to improve with music training but the differences (left-right) did not. None of the tests of performance that utilized noise stimuli showed any improvement with music training. However, gap detection and intensity discrimination using tones demonstrated significant improvement only for the performance in the left ears (χ2 =6.60, df=2, p= 0.0367 for intensity and χ2 =6.72, df=2, p= 0.0347 for gap detection). Laterality did not change with music training with the exception of intensity discrimination for tones (χ2 =7.81, df=2, p= 0.0201).

Listener Age

The relationship between listener age and laterality is not known but there is some indication that adolescent listeners may be strongly lateralized (Sininger, 2008) and therefore the age of listeners in this study was restricted from 18 to 40 years of age. The left ear, right ear and difference scores for all three tests were submitted to a regression analysis with listener age. In only one comparison was the result significant. The left-right difference scores (laterality) for intensity discrimination were found to decrease with age (r2= 0.0107, df=357, p=0.0499).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between stimulus features, specifically spectro-temporal qualities and the symmetry of auditory processing capacity as determined by ear of presentation. Pure tone stimuli have a slow predictable temporal structure and, as the name implies, a pure 1 Hz bandwidth while wide-band noise has a completely random, rapidly changing temporal structure and a very wide spectrum. In a previous study of GDT (Sininger & de Bode, 2008), pure tones and noise stimuli were employed, revealing a significant REA for noise and LEA for tones. The current studies employed three standard auditory psychophysical tasks: frequency discrimination, intensity discrimination, and gap detection. Again, pure tone and wide-band noise were employed with monaural presentations to the left and right ears. Overall, we see a clear advantage for processing of tonal stimuli in the left ear for all measures including gap detection, frequency discrimination and intensity discrimination. However, the REA, seen previously for wide-band noise stimuli was not seen in any of the experiments. In contrast, in the current study noise stimuli produced no apparent laterality, with both ears performing equally. The only suggestion of an explanation of the missing REA comes in the analysis of results by listener sex. Female subjects demonstrate the expected pattern but with a non-significant REA for noise stimuli while male subjects show a LEA for both noise and tones. The previous study (Sininger & de Bode, 2008) did not find a significant effect of sex, with the expected pattern (noise showing a REA and tones a LEA) demonstrated in both sexes.

The reason for the loss of the REA for noise is not clear. The current and previous (Sininger & de Bode, 2008) gap detection experiments were conducted on the same population of listeners, with the same gender, age, and handedness characteristics. A small change in the gap detection procedure was made in the current study, using a logarithmic duration change in the gap duration to avoid 0 ms gaps. It was reasoned, however, that such procedural changes should have a similar effect on each ear.

There have been a number of GDT studies using broad band noise that have investigated ear asymmetry of the process. Some studies, like Sininger & de Bode, have found the REA when using broad-band stimuli (Brown & Nicholls, 1997; Nicholls, Schier, Stough, & Box, 1999; Sulakhe et al., 2003) while in others it has been conspicuously absent (Oxenham, 2000; Baker, Jayewardene, Sayle, & Saeed, 2008; Grose, 2008). Sininger (2008) found a highly significant REA for noise (and LEA for tones) using gap detection in school-aged children (7 to 11 years of age) and speculated that subject age might be an important factor. However, the contrasting results of the present investigation and our previous study (Sininger & de Bode, 2008) used subjects with the same range and mean age. How stimulus and/or subject factors may be interacting to show or hide the REA remains completely unclear. Music training did not affect GDTs nor intensity discrimination for noise and is not a candidate factor. Nor did age influence these measurements, at least in the range evaluated in this study. Gender seems to influence the stimulus-related laterality and this study seems to show that only females tended to reverse laterality for noise and tonal stimuli. However, Baker (2008) used a majority of female subjects and found no REA for gaps in noise. The REA for noise stimuli remains elusive.

In contrast the LEA for tonal stimuli was found for all experiments. It is of interest that only the 1000 Hz tones, and not 500 Hz nor 4000 Hz demonstrated the LEA for frequency and intensity discrimination. For gap detection, only the 4000 Hz tone demonstrated a significant LEA. However, there is a clear trend toward LEA for all tonal stimuli (as seen in the figures) and the lack of significance for some conditions could be due to low power in the study. The selection of 30 subjects was based on significant findings of both LEA and REA by stimulus type for gap detection (Sininger & de Bode, 2008) using the same number of subjects. In retrospect, a larger group may be important to investigate asymmetries in auditory processing.

Right hemisphere processing advantages for tonal stimuli and music have been found repeatedly (Tervaniemi & Hugdahl, 2003; Zatorre et al., 2002; Hyde, Peretz, & Zatorre, 2008), and it is not surprising to see that the left ear also shows such an advantage. However, to our knowledge, the influence of ear of stimulation on basic psychoacoustic abilities using tones has not previously been studied. The current experiments utilized monaural rather than dichotic stimulus presentations and consequently, there was no competition for processing. The monaural capacity illustrated by these results may be useful in predicting the processing capacity of those with unilateral deafness. Preliminary work (Sininger & de Bode, 2008) shows that those with only one ear have a slight advantage for processing tonal stimuli if the left ear is remaining and for processing of wide-band stimuli if they can hear in the right ear. However, this finding has not been replicated.

Task v. Stimulus

The pattern of laterality results by stimulus is the same across the three experiments with LEA for tones and no ear advantage for noise. If task rather than stimulus was driving the laterality, one would predict a consistent REA for gap detection which has not been demonstrated by this study or others. Sininger & de Bode (2008) suggested a possible interaction between task and stimulus when a large REA was found for GDT using broad-band noise. That finding however, was not replicated here. Others have clearly found that the task, rather than stimulus type, determines laterality. For example, Brancucci and colleagues (Brancucci et al., 2005) demonstrated that intensity discrimination for both speech and tones shows a significant LEA while duration discrimination for both stimuli demonstrated a right ear advantage (Brancucci et al., 2008). Our results, in contrast, would argue for stimulus-driven laterality rather than task-driven. This question is clearly in need of further study.

Stimulus Duration

Within the parameters studied (200 to 1000 ms) tone duration had no influence on response laterality. If the right hemisphere is acting as a spectral analyzer, then one would expect some trade off between stimulus duration and analysis capacity. An interaction between stimulus frequency and duration would also be expected yet none was found. It is possible that the 10 ms cosign taper at the onset and offset of stimuli aided in maintaining spectral purity and the durations used may have not taxed the spectral analysis capacity of the system. Thus all durations demonstrated a LEA and the magnitude of the LEA did not change with stimulus duration.

Spectral Width

The distinction between tones and noise is basically found in spectral width. A narrow-band noise centered at 1000 Hz with an acoustic bandwidth of about 450 Hz demonstrated the same pattern of laterality as the wide-band noise demonstrating that the true bandwidth limit for LEA lateralized function is yet to be determined but lies somewhere between 1 and 450 Hz.

Other factors

As expected, laterality of processing was influenced by listener sex. In this study the laterality of processing differed by listener sex primarily for wide-band stimuli. The female listeners gave some indication of stimulus-specific lateralized function (REA for wide-band stimuli) while the male listeners showed only LEA regardless of stimulus type. The extent of the potential influence of sex and the interactions with other factors such as stimulus type was unanticipated from previous experiments. Consequently the numbers of participants was too small to be able to see significance in these influences. The true effect and interactions of factors such as sex and stimulus type may only be revealed with a much larger sample size.

Implications

The results of this study add to a growing body of evidence that the left and right ears demonstrate asymmetric function reflecting the expected hemispheric asymmetry and that the asymmetry is based on the type of stimulus being processed. These experiments demonstrated that when stimuli are presented to the left ear, a slight but consistent advantage is shown when processing tonal stimuli as was seen in previous studies of gap detection (Sininger & de Bode, 2008; Sininger, 2008) and otoacoustic emissions (Sininger & Cone-Wesson, 2004). Similar stimulus-driven lateralized functions occurring at many levels of the auditory system could be explained by the auditory corticofugal system. This system is described by Winer (2006) as “among the largest pathways in the brain” with descending projections from the cerebral cortex to the brainstem suggesting that the ascending auditory pathways receive “significant descending input.” Clearly, the auditory cortex, which has been shown to be involved in lateralized auditory processing in adults could be driving laterality at all other levels.

While left ear advantages for processing of tones is slight, it remains to be seen if auditory performance could be enhanced by appropriate use of left ear stimulation to access contralateral spectral processing capacity. For deaf users of cochlear implant technology, for example, enjoyment of music is often limited. Those using binaural implants might benefit from separate processing strategies in each ear that could take advantage of the natural capacity of the left and right hemispheres. Lack of knowledge regarding the possibilities of ear specific processing could be limiting the technology used with the deaf and hard of hearing. No current treatment protocols, hearing aid or cochlear implant fitting or processing strategies, take advantage of potential processing differences between the two ears.

Further study of lateralized auditory processing is certainly warranted to define the parameters that dictate laterality and to resolve the discrepancies in the few studies that have looked for this effect. However, given the number of studies that have found lateralized auditory function, including the present study, the assumption that the left and right ears function interchangeably must be challenged.

Table 1.

Stimuli used for the three experimental conditions. Stimulus duration was manipulated during the frequency discrimination experiment and bandwidth (BW) during the intensity discrimination and gap detection experiments.

| STIMULI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noise | 500 Hz | 1000 Hz | 4000 Hz | ||

| EXPERIMENTS | Gap Detection Threshold | Broad-Band 1 s duration |

1 Hz BW 1 s duration |

1 Hz BW 1 s duration |

1 Hz BW 1 s duration |

| Frequency Discrimination | X | Durations: 200 ms 500 ms 1000 ms |

Durations: 200 ms 500 ms 1000 ms |

Durations: 200 ms 500 ms 1000 ms |

|

| Intensity Discrimination | BW: Broad-Band |

BW: 1 Hz |

BW: 1 Hz 500 Hz |

BW: 1 Hz |

|

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by National Institute on Deafness & Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) R01DC008305, Y. Sininger P.I. We wish to acknowledge Hannah Hultine who served as research assistant to this project.

Reference List

- Anderson B, Southern BD, Powers RE. Anatomic asymmetries of the posterior superior temporal lobes: a postmorten study. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1999;12:247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RJ, Jayewardene D, Sayle C, Saeed S. Failure to find asymmetry in auditory gap detection. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition. 2008;13:1–21. doi: 10.1080/13576500701507861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin P, Zilbovicius M, Crozier S, Thivard L, Fontaine A. Lateralization of speech and auditory temporal processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:536–540. doi: 10.1162/089892998562834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilger RC, Matthies ML, Hammel DR, Demorest ME. Genetic implications of gender differences in the prevalence of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. J Speech Hear Res. 1990;33:418–432. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3303.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancucci A, Babiloni C, Rossini PM, Romani GL. Right hemisphere specialization for intensity discrimination of musical and speech sounds. Neuropsychologica. 2005;43:1916–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancucci A, D’Anselmo A, Martello F, Tommasi L. Left hemisphere specialization for duration discrimination of musical and speech sounds. Neuropsychologica. 2008;46:2013–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CP, Fitch RH, Tallal P. Sex and Hemispheric Differences for Rapid Auditory Processing in Normal Adults. Laterality. 1999;4:39–50. doi: 10.1080/713754320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Nicholls ME. Hemispheric asymmetries for the temporal resolution of brief auditory stimuli. Percept Psychophys. 1997;59:442–447. doi: 10.3758/bf03211910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns EM, Arehart KH, Campbell SL. Prevalence of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in neonates. ARO Abstracts. 1991;66 doi: 10.1121/1.402438. Ref Type: Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahani M, Paul G, Shahar A. Tinnitus asymmetry. Audiology. 1984;23:127–135. doi: 10.3109/00206098409072827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung DY, Mason K, Gannon RP, Willson GN. The ear effect as a function of age and hearing loss. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1983;73:1277–1282. doi: 10.1121/1.389276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll C, Kei J, McPherson B. Handedness Effects on Transient Evoked Otoacoustic Emissions in Schoolchildren. J Am Acad Audiol. 2002;13:403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge L, Salamy A. Functional auditory development in preterm and full term infants. Early Hum Dev. 1996;45:215–228. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(96)01732-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind N, Levitsky W. Human brain: Left-right asymmetries in temporal speech region. Science. 1968;161:186–187. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3837.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good CD, Johnsrude I, Ashburner J, Henson RNA, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RSJ. Cerebral Asymmetry and the Effects of Sex and Handedness on Brain Structure: A Voxel-Based Morphometric Analysis of 465 Normal Adult Human Brains. NeuroImage. 2001;14:685–700. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose JH. Gap Detection and Ear of Presentation: Examination of Diparate Findings. Ear & Hearing. 2008;29:228–238. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31818bc150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsler JJ. The specialized structure of human language cortex: Pyramidal cell size asymmetries within auditory and language-associated regions of the temporal lobes. Brain and Language. 2003;86:226–242. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00531-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KL, Peretz I, Zatorre RJ. Evidence for the role of the right auditory cortex in fine pitch resolution. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail H, Thornton ARD. The interaction between ear and sex differences and stimulus rate. Hearing Research. 2003;179:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SJ, Byrne C. The AEP T-complex to synthesised musical tones: left-right asymmetry in relation to handedness and hemisphere dominance. Electroencephalgr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;108:355–160. doi: 10.1016/s0168-5597(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallman Hj. Ear asymmetries with monaurally-presented sounds. Neuropsychologia. 1977;15:833–835. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(77)90017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallman Hj, Corballis MC. Ear asymmetry in reaction time to musical sounds. Perception & Psychophysics. 1975;17:368–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan PM, Lipscomb DM. Bilateral hearing asymmetry in a large population. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1974;55:1092–1094. doi: 10.1121/1.1914657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D. Cerebral Dominance and the Perception of Verbal Stimuli. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1961;15:166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D. Speech Lateralization in young children as determined by an auditory test. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1963;56:899–902. doi: 10.1037/h0047762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D. Left-ear differences in the perception of melodies. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1964;16:355–358. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D. The Asymmetry of the human brain. Scientific American. 1973;228:70–78. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0373-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King FL, Kimura D. Left-ear superiority in dichotic perception of vocal nonverbal sounds. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1972;26:111–116. doi: 10.1037/h0082420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht S, Drager B, Deppe M, Bobe L, Lohmann H, Floel A, et al. Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain. 2000;123:2512–2518. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RA, McGaffigan PM. Right-left asymmetries in the human brain stem: auditory evoked potentials. Electroencephalgr Clin Neurophysiol. 1983;55:532–537. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlone J. Sex differences in human brain asymmetry: a critical survey. Behav Brain Sci. 1980;3:215–263. [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK. The human auditory brain stem as a generator of auditory evoked potentials. Hearing Research. 1987;29:33–43. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark M, Merlob P, Bresloff I, Olsha M, Attias J. Click evoked otoacoustic emissions: inter-aural and gender differences in newborns. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;8:133–139. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.1997.8.3.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls ME, Schier M, Stough CK, Box A. Psychophysical and electrophysiologic support for a left hemisphere temporal processing advantage. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology. 1999;12:11–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham AJ. Influence of spatial and temporal coding on auditory gap detection. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2000;107:2215–2223. doi: 10.1121/1.428502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirila T. Left-right asymmetry in the human response to experimental noise exposure. II. Pre-exposure hearing threshold and temporary threshold shift at 4 kHz frequency. Acta Otolaryngol. 1991;111:861–866. doi: 10.3109/00016489109138422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirila T, Jounio-Ervasti K, Sorri M. Left-right asymmetries in hearing threshold levels in three age groups of a random population. Audiology. 1992;31:150–161. doi: 10.3109/00206099209072910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross B, Herdman AT, Pantev C. Right Hemispheric Laterality of Human 40 Hz Auditory Steady-state Responses. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:2029–2039. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonwiesner M, Rubsamen R, von Cramon DY. Hemispheric asymmetry for spectral and temporal processing in the human antero-lateral auditory belt cortex. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;22:1521–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Pugh KR, Constable RT, Skudierski P, Fulbright RK, et al. Sex differences in the functional organization of the brain for language. Nature. 1995;373:607–609. doi: 10.1038/373607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidtis JJ. On the nature of the cortical function underlying right hemisphere auditory perception. Neuropsychologia. 1980;18:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(80)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidtis JJ. Predicting brain organization from dichotic listening performance: Cortical and subcortical functional asymmetries contribute to perceptual asymmetries. Brain and Language. 1982;17:287–300. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(82)90022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sininger YS. Factors Influencing Laterality of Gap Detection: Response to Grose. Ear & Hearing. 2008;29:979–981. [Google Scholar]

- Sininger YS, Cone-Wesson B. Asymmetric cochlear processing mimics hemispheric specialization. Science. 2004;305:1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1100646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sininger YS, de Bode S. Asymmetry of Temporal Processing in Normally Hearing and Unilaterally Deaf Subjects. Ear & Hearing. 2008;29:228–238. doi: 10.1097/aud.0b013e318164537b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sininger YS, Cone-Wesson B. Lateral asymmetry in the ABR of neonates: Evidence and mechanisms. Hearing Research. 2006;212:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulakhe N, Elias LJ, Lejbak L. Hemispheric asymmetries for gap detection depend on noise type. Brain and Cognition. 2003;53:372–375. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervaniemi M, Hugdahl K. Lateralization of auditory-cortex functions. Brain Research Reviews. 2003;43:231–246. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervaniemi M, Medvedev SVA, Alho K, Pakhomov SV, Roudas MS, van Zuijen TL, et al. Lateralized automatic auditory processing of phonetic versus musical information: A PET study. Human Brain Mapping. 2000;10:74–79. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200006)10:2<74::AID-HBM30>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA. Decoding the auditory corticofugal systems. Hearing Research. 2006;212:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki T, Goto Y, Taniwaki T, Kinukawa N, Kira Ji, Tobimatsu S. Left hemisphere specialization for rapid temporal processing: a study with auditory 40 Hz steady-state responses. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ, Belin P. Spectral and Temporal Processing in Human Auditory Cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11:953. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ, Belin P, Penhune VB. Structure and function of auditory cortex: music and speech. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01816-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ, Evans AC, Meyer E, Gjedde A. Lateralization of phonetic and pitch discrimination in speech processing. Science. 1992;256:846–849. doi: 10.1126/science.1589767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]