Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a group of small, noncoding RNAs that act as novel regulators of gene expression through the post-transcriptional repression of their target mRNAs. miRNAs have been implicated in diverse biologic processes, and it is estimated that up to half of all transcripts are regulated by miRNAs. Recent studies also demonstrate a critical role for miRNAs in renal development, physiology, and pathophysiology. Understanding the function of miRNAs in the kidney may lead to innovative approaches to renal disease.

In 1993, the first microRNA (miRNA), lin-4, was described in Caenorhabditis elegans.1 The phenomenon of a small RNA that repressed gene expression was initially thought of as a unique means of controlling developmental timing in the nematode. Over the past two decades, it has become clear that miRNA-mediated regulation of gene expression also occurs in multiple biologic processes and is conserved from plants to animals; over 19,000 miRNAs have been reported in 153 species (miRBase, version 17).2 Currently, it is estimated that at least half of all transcripts are regulated by miRNAs.3 There are several current, comprehensive reviews of miRNAs and their roles in the kidney.4–10 This article highlights recent novel insights into miRNA function and the implications for miRNAs in renal disease.

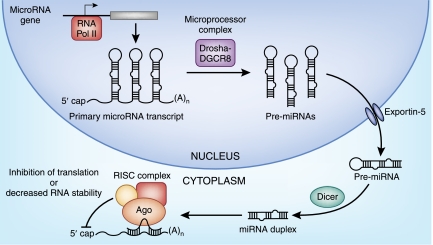

miRNAs are small, endogenous, noncoding RNAs that bind to their respective target mRNAs and recruit the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) shown in Figure 1. After recruitment of RISC, miRNAs usually decrease expression of their mRNA targets through translational repression, deadenylation, or enhanced mRNA decay.11 Bioinformatic analysis of conserved miRNA target sites suggests that mammalian miRNAs have on average approximately 300 mRNA targets per miRNA family.12 With few exceptions, the key feature of miRNA target recognition is mRNA sequence complementarity to an eight-nucleotide (nt) seed miRNA sequence found in the 3′-untranslated region.13 The sequence context in which the miRNA target site resides confers additional specificity to miRNA-mRNA interactions, and conservation of specific miRNA target sites in mRNAs across species is predictive of biologically relevant miRNA-mRNA interactions.14

Figure 1.

The biogenesis of miRNAs. Primary miRNA transcripts are transcribed by RNA polymerase II and processed by the microprocessor complex (DGCR8/Drosha) into precursor stem-loop miRNAs in the nucleus. Precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) are exported into the cytoplasm by Exportin-5 and are cleaved by Dicer to produce mature miRNAs. Mature miRNAs recognize their respective target mRNAs and mediate post-transcriptional repression of their targets through translational repression, deadenylation, or enhanced mRNA decay.

Gene regulation mediated by miRNA has distinct features when compared with transcription factor regulatory networks.15 Experimental approaches to identify miRNA targets show that the degree of miRNA repression is relatively modest for individual proteins and that individual miRNAs modulate the expression of hundreds to thousands of proteins.16,17 Another distinguishing feature is the speed and potential reversibility of miRNA repression because miRNAs act at the site of protein production, the ribosome.18 Furthermore, miRNAs distribute to different subcellular compartments according to their association with the site of protein translation.19,20 Broadly speaking, miRNAs fine-tune existing transcriptional programs in magnitude, time, and space.

An additional layer of complexity is conferred in the regulation of miRNA production and function. Much like other genes, transcription of miRNA genes is largely dependent on transcription factors. Recently, candidate miRNA promoters have been systematically identified using chromatin immunoprecipitation–sequencing data for chromatin marks specific to transcriptional initiation sites, and linked to the binding of embryonic stem cell-specific transcription factors.21 This type of information reveals how miRNAs and transcription factors are integrated into gene regulatory networks.15

A large number of miRNAs are also subject to post-transcriptional regulation.22,23 Generally, RNA polymerase II generates the primary miRNA transcript, which is processed by the microprocessor complex in the nucleus to produce stem-loop precursor miRNAs (Figure 1). The precursor miRNA is subsequently cleaved by Dicer to form mature functional miRNA. There is evidence that the processing of primary miRNA transcripts and precursor miRNAs is regulated in different cell types, resulting in differential expression of mature miRNAs.22,23 In addition, the primary transcripts of some miRNA genes undergo RNA editing by adenosine deaminases acting on RNAs that convert adenosine to inosine, resulting in changes in the target specificity of the mature miRNA.24,25 Finally, although most miRNAs repress their respective target mRNAs, some miRNAs also activate targets depending on the cellular context.26

The discovery of miRNAs as critical regulators of fundamental biologic processes led to the emergence of a new field of study: the role of miRNAs in normal renal development, physiology, and pathophysiology. Several recent studies demonstrated that miRNAs are essential in specific tissue lineages using a conditional approach to knock down Dicer, which is required for the production of functional miRNAs (Figure 1). In the kidney, conditional Dicer models have been reported for nephron progenitors, ureteric epithelium, podocytes, proximal tubules, and juxtaglomerular cells.27–33 During kidney development, the global loss of miRNAs in nephron progenitors results in a premature depletion of this population and, as a consequence, a marked decrease in nephron number.29,30 This is mediated by increased apoptosis and upregulation of the pro-apoptotic protein Bim in the absence of miRNAs.29 In contrast, removal of Dicer function from the ureteric lineage results in cystic kidney disease in association with aberrant proliferation, apoptosis, and branching morphogenesis.30

Podocyte-specific loss of Dicer activity causes proteinuria, foot process effacement, and glomerulosclerosis with rapid progression to renal failure.27,28,32 Although the initial specification of podocytes occurs normally in these mice, the maintenance of podocyte structure and function requires miRNA function. The inducible deletion of another miRNA processing enzyme, Drosha, in podocytes in 2- to 3-month-old mice also results in a similar phenotype, demonstrating an ongoing need for miRNA activity in mature podocytes.34 Mice with a Dicer deletion in renin-secreting cells in the juxtaglomerular apparatus demonstrate loss of juxtaglomerular cells, striped fibrosis, and vascular abnormalities.31 Interestingly, the loss of miRNAs in the proximal tubule after 3 weeks of age confers resistance to ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice.33

These initial studies provide crucial insights into a functional requirement for miRNAs in multiple cell lineages in the kidney. However, defining biologically relevant miRNA-mRNA target interactions remains a challenge. Experiments using microarray or proteomic analysis after alterations in miRNA expression have been used to develop and validate bioinformatic algorithms that predict target interactions.16,17 These algorithms are hampered by a high false-positive prediction rate and can fail to predict the most biologically important miRNA targets.35 Nevertheless, they remain a powerful tool and are the basis for the identification of several miRNA-mRNA target interactions that have been verified experimentally.

A more recent approach involves high-throughput RNA sequencing of RISC-bound RNA fragments, which allows for the identification of RISC-associated miRNAs and their target mRNAs.36–38 The experimental and bioinformatic approaches to miRNA target identification are becoming more robust as the determinants of miRNA-mRNA interactions are better defined. A further consideration is the experimental observation that miRNAs regulate many hundreds of proteins, often in related signaling pathways. Thus, rather than conceptualizing miRNA function as repression of a critical single transcript, it may be more informative to describe miRNA activity in the modulation of signaling pathways at multiple levels as part of larger regulatory networks.39

The evidence that miRNAs are crucial in normal kidney development and physiology leads naturally to the question of what role miRNAs play in kidney disease. Research over the past several years has focused on the analysis of differential miRNA expression in renal disease and in the study of specific miRNAs that regulate pathologic processes (see recent reviews for a systematic description4,5,8,10). These studies implicate TGF β regulation of miRNA expression in diabetic nephropathy,40–43 p53 induction of miR-34a in ischemic acute kidney injury,44 and miR-15a regulation of the cell cycle regulator Cdc25A.45 The best studied of these is diabetic nephropathy. Natarajan and colleagues observe upregulation of miR-192, miR-216a, and miR-217 in response to TGFβ signaling in a rodent diabetic mouse model and in glomerular mesangial cells.41–43 Furthermore, they identified targets, such as SIP1, PTEN, and Ybx1, that may play critical roles in collagen expression and diabetic nephropathy.41–43 However, renal biopsies of patients with diabetic nephropathy show significantly lower miR-192 expression; resolving this apparent discrepancy will require further study.46 In other studies, miR-335 and miR-43a promote renal cell senescence and aging by suppressing mitochondrial antioxidative enzymes,47 and miR-192 mediates WNK1-regulated sodium and potassium balance48 and TGFβ-driven fibrosis.49 Differential miRNA profiling as a systems biology approach is also being used in a variety of settings in rodent disease models and renal biopsy samples, including acute kidney injury,33 polycystic kidney disease,50,51 acute rejection,52,53 renal cell carcinoma,54,55 lupus nephritis,56 and IgA nephropathy.57 Thus, investigators are only beginning to elucidate the pathologic mechanisms that are regulated by miRNAs during kidney disease.

What does all this mean for patients with kidney disease? With the emerging data associating miRNA expression patterns to different stages of renal disease, one application is the use of miRNAs as novel biomarkers for diagnostic and prognostic purposes. One of the distinguishing features of miRNAs is their stability—indeed, one recent study suggests their average half-life may be approximately 5 days.58 Furthermore, miRNAs are transported in the plasma59 and can be isolated from urine,60,61 increasing their potential utility as biomarkers.

miRNAs also have significant promise as novel drug targets, particularly given the rapidly increasing knowledge about miRNA regulatory networks in renal pathophysiology. Several experimental approaches to modulate miRNA activity in vivo are in development. Chemically engineered oligonucleotides, termed antagomirs, successfully target endogenous miRNAs in mammals and can target miRNAs in the kidney.10,62 Alternatively, locked nucleic acid–modified oligonucleotides have been used in a nonhuman primate model with chronic hepatitis C virus infection to repress miR-122.63 Other approaches include the development of miRNA sponges, in which miRNA-binding sites are stably introduced into the genome to sequester endogenous miRNAs, or the introduction of oligonucleotide target maskers that protect miRNA targets against miRNA-mediated repression.10,64

There has been an incredible explosion of information regarding miRNAs since their initial discovery less than two decades ago, and there remains much to learn about miRNA-mediated regulation of normal and abnormal kidney function. Although many challenges remain, understanding the role of miRNAs in renal pathology offers the hope of innovative approaches to novel therapies for renal diseases.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

J.H.’s laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1K99DK087922 and the Pennsylvania Department of Health. J.A.K.’s laboratory is supported by National Institutes for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant 1R01DK087794-01A1 and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V: The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75: 843–854, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S: miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 39[Database issue]: D152–D157, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajewsky N: microRNA target predictions in animals. Nat Genet 38[Suppl]: S8–S13, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatt K, Mi QS, Dong Z: microRNAs in kidneys: biogenesis, regulation, and pathophysiological roles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F602–F610, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li JY, Yong TY, Michael MZ, Gleadle JM: Review: The role of microRNAs in kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 15: 599–608, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wessely O, Agrawal R, Tran U: MicroRNAs in kidney development: Lessons from the frog. RNA Biol 7: 296–299, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karolina DS, Wintour EM, Bertram J, Jeyaseelan K: Riboregulators in kidney development and function. Biochimie 92: 217–225, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato M, Arce L, Natarajan R: MicroRNAs and their role in progressive kidney diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1255–1266, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saal S, Harvey SJ: MicroRNAs and the kidney: Coming of age. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 317–323, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorenzen JM, Haller H, Thum T: MicroRNAs as mediators and therapeutic targets in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 7: 286–294, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djuranovic S, Nahvi A, Green R: A parsimonious model for gene regulation by miRNAs. Science 331: 550–553, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP: Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 19: 92–105, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP: MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: Determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell 27: 91–105, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobert O: Gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Science 319: 1785–1786, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baek D, Villén J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP: The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455: 64–71, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N: Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 455: 58–63, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W: Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell 125: 1111–1124, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashraf SI, McLoon AL, Sclarsic SM, Kunes S: Synaptic protein synthesis associated with memory is regulated by the RISC pathway in Drosophila. Cell 124: 191–205, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schratt GM, Tuebing F, Nigh EA, Kane CG, Sabatini ME, Kiebler M, Greenberg ME: A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature 439: 283–289, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marson A, Levine SS, Cole MF, Frampton GM, Brambrink T, Johnstone S, Guenther MG, Johnston WK, Wernig M, Newman J, Calabrese JM, Dennis LM, Volkert TL, Gupta S, Love J, Hannett N, Sharp PA, Bartel DP, Jaenisch R, Young RA: Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell 134: 521–533, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee EJ, Baek M, Gusev Y, Brackett DJ, Nuovo GJ, Schmittgen TD: Systematic evaluation of microRNA processing patterns in tissues, cell lines, and tumors. RNA 14: 35–42, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson JM, Newman M, Parker JS, Morin-Kensicki EM, Wright T, Hammond SM: Extensive post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs and its implications for cancer. Genes Dev 20: 2202–2207, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawahara Y, Zinshteyn B, Chendrimada TP, Shiekhattar R, Nishikura K: RNA editing of the microRNA-151 precursor blocks cleavage by the Dicer-TRBP complex. EMBO Rep 8: 763–769, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YK, Heo I, Kim VN: Modifications of small RNAs and their associated proteins. Cell 143: 703–709, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA: Switching from repression to activation: MicroRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science 318: 1931–1934, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey SJ, Jarad G, Cunningham J, Goldberg S, Schermer B, Harfe BD, McManus MT, Benzing T, Miner JH: Podocyte-specific deletion of dicer alters cytoskeletal dynamics and causes glomerular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2150–2158, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho J, Ng KH, Rosen S, Dostal A, Gregory RI, Kreidberg JA: Podocyte-specific loss of functional microRNAs leads to rapid glomerular and tubular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2069–2075, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho J, Pandey P, Schatton T, Sims-Lucas S, Khalid M, Frank MH, Hartwig S, Kreidberg JA: The pro-apoptotic protein Bim is a microRNA target in kidney progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1053–1063, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagalakshmi VK, Ren Q, Pugh MM, Valerius MT, McMahon AP, Yu J: Dicer regulates the development of nephrogenic and ureteric compartments in the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int 79: 317–330, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sequeira-Lopez ML, Weatherford ET, Borges GR, Monteagudo MC, Pentz ES, Harfe BD, Carretero O, Sigmund CD, Gomez RA: The microRNA-processing enzyme dicer maintains juxtaglomerular cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 460–467, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi S, Yu L, Chiu C, Sun Y, Chen J, Khitrov G, Merkenschlager M, Holzman LB, Zhang W, Mundel P, Bottinger EP: Podocyte-selective deletion of dicer induces proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2159–2169, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei Q, Bhatt K, He HZ, Mi QS, Haase VH, Dong Z: Targeted deletion of Dicer from proximal tubules protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 756–761, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhdanova O, Srivastava S, Di L, Li Z, Tchelebi L, Dworkin S, Johnstone DB, Zavadil J, Chong MM, Littman DR, Holzman LB, Barisoni L, Skolnik EY: The inducible deletion of Drosha and microRNAs in mature podocytes results in a collapsing glomerulopathy. Kidney Int 80: 719–730, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas M, Lieberman J, Lal A: Desperately seeking microRNA targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 1169–1174, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB: Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature 460: 479–486, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M, Jr, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, Ulrich A, Wardle GS, Dewell S, Zavolan M, Tuschl T: Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141: 129–141, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zisoulis DG, Lovci MT, Wilbert ML, Hutt KR, Liang TY, Pasquinelli AE, Yeo GW: Comprehensive discovery of endogenous Argonaute binding sites in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 173–179, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shirdel EA, Xie W, Mak TW, Jurisica I: NAViGaTing the micronome—using multiple microRNA prediction databases to identify signalling pathway-associated microRNAs. PLoS ONE 6: e17429, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato M, Arce L, Wang M, Putta S, Lanting L, Natarajan R: A microRNA circuit mediates transforming growth factor-β1 autoregulation in renal glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int 80: 358–368, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato M, Putta S, Wang M, Yuan H, Lanting L, Nair I, Gunn A, Nakagawa Y, Shimano H, Todorov I, Rossi JJ, Natarajan R: TGF-beta activates Akt kinase through a microRNA-dependent amplifying circuit targeting PTEN. Nat Cell Biol 11: 881–889, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato M, Wang L, Putta S, Wang M, Yuan H, Sun G, Lanting L, Todorov I, Rossi JJ, Natarajan R: Post-transcriptional up-regulation of Tsc-22 by Ybx1, a target of miR-216a, mediates TGF-beta-induced collagen expression in kidney cells. J Biol Chem 285: 34004–34015, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kato M, Zhang J, Wang M, Lanting L, Yuan H, Rossi JJ, Natarajan R: MicroRNA-192 in diabetic kidney glomeruli and its function in TGF-beta-induced collagen expression via inhibition of E-box repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 3432–3437, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhatt K, Zhou L, Mi QS, Huang S, She JX, Dong Z: MicroRNA-34a is induced via p53 during cisplatin nephrotoxicity and contributes to cell survival. Mol Med 16: 409–416, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee SO, Masyuk T, Splinter P, Banales JM, Masyuk A, Stroope A, Larusso N: MicroRNA15a modulates expression of the cell-cycle regulator Cdc25A and affects hepatic cystogenesis in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest 118: 3714–3724, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krupa A, Jenkins R, Luo DD, Lewis A, Phillips A, Fraser D: Loss of MicroRNA-192 promotes fibrogenesis in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 438–447, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bai XY, Ma Y, Ding R, Fu B, Shi S, Chen XM: miR-335 and miR-34a Promote renal senescence by suppressing mitochondrial antioxidative enzymes. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1252–1261, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elvira-Matelot E, Zhou XO, Farman N, Beaurain G, Henrion-Caude A, Hadchouel J, Jeunemaitre X: Regulation of WNK1 expression by miR-192 and aldosterone. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1724–1731, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chung AC, Huang XR, Meng X, Lan HY: miR-192 mediates TGF-beta/Smad3-driven renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1317–1325, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pandey P, Brors B, Srivastava PK, Bott A, Boehn SN, Groene HJ, Gretz N: Microarray-based approach identifies microRNAs and their target functional patterns in polycystic kidney disease. BMC Genomics 9: 624, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandey P, Qin S, Ho J, Zhou J, Kreidberg JA: Systems biology approach to identify transcriptome reprogramming and candidate microRNA targets during the progression of polycystic kidney disease. BMC Syst Biol 5: 56, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anglicheau D, Sharma VK, Ding R, Hummel A, Snopkowski C, Dadhania D, Seshan SV, Suthanthiran M: MicroRNA expression profiles predictive of human renal allograft status. Proc Natl Acad Aci USA 106: 5330–5335, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sui W, Dai Y, Huang Y, Lan H, Yan Q, Huang H: Microarray analysis of MicroRNA expression in acute rejection after renal transplantation. Transpl Immunol 19: 81–85, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chow TF, Mankaruos M, Scorilas A, Youssef Y, Girgis A, Mossad S, Metias S, Rofael Y, Honey RJ, Stewart R, Pace KT, Yousef GM: The miR-17-92 cluster is over expressed in and has an oncogenic effect on renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 183: 743–751, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chow TF, Youssef YM, Lianidou E, Romaschin AD, Honey RJ, Stewart R, Pace KT, Yousef GM: Differential expression profiling of microRNAs and their potential involvement in renal cell carcinoma pathogenesis. Clin Biochem 43: 150–158, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dai Y, Sui W, Lan H, Yan Q, Huang H, Huang Y: Comprehensive analysis of microRNA expression patterns in renal biopsies of lupus nephritis patients. Rheumatol Int 29: 749–754, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang G, Kwan BC, Lai FM, Choi PC, Chow KM, Li PK, Szeto CC: Intrarenal expression of microRNAs in patients with IgA nephropathy. Lab Invest 90: 98–103, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gantier MP, McCoy CE, Rusinova I, Saulep D, Wang D, Xu D, Irving AT, Behlke MA, Hertzog PJ, Mackay F, Williams BR: Analysis of microRNA turnover in mammalian cells following Dicer1 ablation. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 5692–5703, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vickers KC, Remaley AT: MicroRNAs in atherosclerosis and lipoprotein metabolism. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 17: 150–155, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang G, Kwan BC, Lai FM, Chow KM, Kam-Tao Li P, Szeto CC: Expression of microRNAs in the urinary sediment of patients with IgA nephropathy. Dis Markers 28: 79–86, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamada Y, Enokida H, Kojima S, Kawakami K, Chiyomaru T, Tatarano S, Yoshino H, Kawahara K, Nishiyama K, Seki N, Nakagawa M: MiR-96 and miR-183 detection in urine serve as potential tumor markers of urothelial carcinoma: Correlation with stage and grade, and comparison with urinary cytology. Cancer Sci 102: 522–529, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krützfeldt J, Rajewsky N, Braich R, Rajeev KG, Tuschl T, Manoharan M, Stoffel M: Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature 438: 685–689, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, Persson R, Lindow M, Munk ME, Kauppinen S, Ørum H: Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science 327: 198–201, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davidson BL, McCray PB, Jr: Current prospects for RNA interference-based therapies. Nat Rev Genet 12: 329–340, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]