Abstract

A novel alphaproteobacterium isolated from freshwater sediments, strain pMbN1, degrades 4-methylbenzoate to CO2 under nitrate-reducing conditions. While strain pMbN1 utilizes several benzoate derivatives and other polar aromatic compounds, it cannot degrade p-xylene or other hydrocarbons. Based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, strain pMbN1 is affiliated with the genus Magnetospirillum.

TEXT

Aromatic compounds are structurally diverse and abundant in nature, ranging from alkylbenzenes and other crude oil components to lignin monomers and amino acids. Under anoxic conditions, which prevail in many habitats, most monoaromatic compounds are channeled via compound-specific reaction sequences into the central anaerobic benzoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) pathway for further degradation (5, 10). Among alkylbenzenes, p-xylene seems to be particularly difficult to degrade under anoxic conditions; for example, enrichment cultures of nitrate- (31) and sulfate-reducing bacteria (29, 44) with crude oil as the only source of organic carbon readily consumed o- and m-alkyltoluenes, but not the p-alkylated isomers. Attempts to isolate anaerobic bacteria growing with p-xylene as the sole source of carbon and energy have thus far not transcended the level of enrichment cultures (12, 25, 32, 46). The recalcitrance of p-xylene is unlikely to result from difficulties with initial substrate activation, since early experiments with anaerobically toluene-degrading bacteria demonstrated p-xylene conversion to 4-methylbenzoate as a dead-end metabolite (4, 27) and analysis of p-xylene-consuming enrichment cultures revealed formation of (4-methylbenzyl)succinate as the initial metabolite (3, 25, 32). Thus, the subsequent degradation of 4-methylbenzoate appears to be the bottleneck in anaerobic p-xylene degradation, agreeing with the inability of presently known alkylbenzene-degrading (facultatively) anaerobic isolates to utilize 4-methylbenzoate (Table 1) (for an overview, see reference 42). Moreover, studies with wastewater-treating anaerobic bioreactors demonstrated the markedly longer time requirement for 4-methylbenzoate degradation than that for benzoate and phthalate isomers (16).

Table 1.

Anaerobically alkylbenzene- and alkyl benzoate-degrading proteobacteriaa

| Organism | Subgroup of Proteobacteria | Substrate for anaerobic growth |

Cometabolic conversion of p-xylene to 4-methylbenzoated | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkylbenzeneb | Benzoate/alkylbenzoatec | ||||

| Nitrate-reducing bacteria | |||||

| Thauera aromatica K172 | Beta- | Toluene | Benzoate | + | 2, 4 |

| “Aromatoleum aromaticum” EbN1 | Beta- | Toluene, ethylbenzene | Benzoate | ND | 28 |

| “Aromatoleum” sp. pCyN1 | Beta- | Toluene, p-cymene, p-ethyltoluene | Benzoate, 4-isopropylbenzoate, 4-ethylbenzoate | ND | 13 |

| Magnetospirillum sp. pMbN1 | Alpha- | Benzoate, 3-methylbenzoate, 4-methylbenzoate | ND | This study | |

| Sulfate-reducing bacteria | |||||

| Desulfobacula toluolica strain Tol2 | Delta- | Toluene | Benzoate | + | 27, 30 |

| Strain oXyS1 | Delta- | Toluene, o-xylene | Benzoate, 2-methylbenzoate | ND | 14 |

| Strain mXyS1 | Delta- | Toluene, m-xylene | Benzoate, 3-methylbenzoate | ND | 14 |

| Iron-reducing bacterium | |||||

| Geobacter metallireducens GS15 | Delta- | Toluene | Benzoate | ND | 20 |

| Phototrophic bacterium | |||||

| Blastochloris sulfoviridis ToP1 | Alpha- | Toluene | Benzoate | ND | 48 |

For a detailed overview of anaerobically alkylbenzene-degrading bacteria, see reference 43.

None of the listed strains is capable of anaerobic degradation of p-xylene.

Except for Magnetospirillum sp. pMbN1, none of the listed strains is capable of anaerobically degrading 4-methylbenzoate.

Toluene-utilizing cells cometabolically convert p-xylene into 4-methylbenzoate as a dead-end product. +, positive for conversion; ND, not determined.

In the present study, enrichment of bacteria degrading 4-methylbenzoate under nitrate-reducing conditions was attempted in defined mineral medium (28) at 28°C in 250-ml bottles containing 200 ml of mineral medium, 15 ml of mud mixture (collected from ditches and the Weser River in Bremen, Germany), 1.5 mM 4-methylbenzoate, and 5 mM NaNO3. Nitrate consumption was monitored by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), and nitrate was several times replenished upon depletion. The initial enrichment culture grew within 14 days. The sediment-free subcultures obtained after four transfers displayed a doubling time of 10 h, resembling those of earlier reported enrichments with 4-methylbenzoate and nitrate (13). After several passages, the sediment-free enrichment cultures were dominated by spirillum-shaped cells. Isolation of 4-methylbenzoate-degrading nitrate-reducing bacteria was then attempted with anoxic agar-dilution series (41). Whitish colonies were retrieved by means of finely-drawn Pasteur pipettes and transferred to liquid media. The best-growing strain was chosen for further analysis and designated pMbN1. For further cultivation of strain pMbN1 under nitrate-reducing conditions, the reductant ascorbate (4 mM) was routinely added to the mineral medium. All of the following growth experiments were conducted in triplicate. Additional information on materials and methods is provided in the supplemental material.

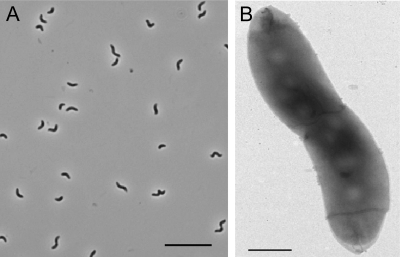

The isolate strain pMbN1 had a spirillum-like shape (Fig. 1) with dimensions of 1.8 to 3.6 μm by 0.6 to 0.8 μm. Cells stained as Gram-negative and were motile. However, they did not display a magnetotactic response during microaerobic growth (33; D. Schüler, personal communication). Strain pMbN1 did not grow on solid media (rich or mineral) under oxic or nitrate-reducing conditions; anaerobic incubation of plates was carried out at 28°C in jars under an N2 atmosphere as recently described (45).

Fig 1.

Micrographs of strain pMbN1. (A) Phase contrast micrograph. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Electron micrograph of negatively stained cell. Bar, 0.5 μm.

The temperature range of anaerobic growth of strain pMbN1 with 4-methylbenzoate was tested in a temperature gradient block. The observed temperature range of growth was 11.9 to 37.2°C, with an optimum range of 26.2 to 35.7°C (determined by means of maximal growth rates [μmax]; see the Arrhenius plot in Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). All subsequent cultures were incubated at 28°C. The pH range of anaerobic growth with 4-methylbenzoate was pH 6.8 to pH 8.0, with an optimum around pH 7.3 to pH 7.7 (determined using μmax; see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material).

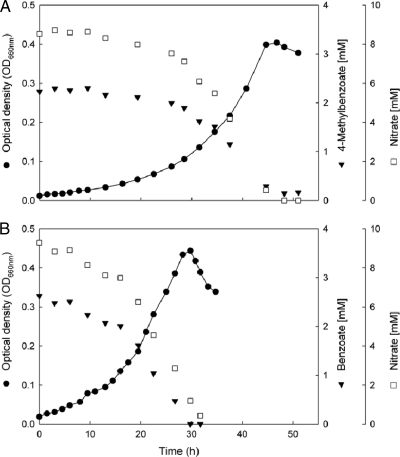

Approximate doubling times of strain pMbN1 during anaerobic growth with 4-methylbenzoate and benzoate were 9.5 h (specific μmax, 0.10 h−1) and 6.1 h (specific μmax, 0.16 h−1), respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Anaerobic growth of strain pMbN1 with benzoates under nitrate-reducing conditions. (A) With 4-methylbenzoate. (B) With benzoate. Symbols are as indicated along the y axes. No intermediate formation of nitrite could be detected.

In addition to 4-methylbenzoate, a wide range of other benzoate derivatives, phenylpropanoids, and aliphatic carboxylates were anaerobically utilized by strain pMbN1. All compounds tested for supporting aerobic or anaerobic growth are indicated together with the applied concentrations in Table 2. Remarkably, strain pMbN1 could not grow anaerobically with other 4-alkylbenzoates, p-xylene, or other hydrocarbons, indicating a specialization for benzoate derivatives and simple aliphatic carboxylates. Although strain pMbN1 is facultatively aerobic, it could degrade only a few aromatic compounds under oxic conditions. The nutritional specialization of strain pMbN1 is further underpinned by its inability to utilize amino acids or carbohydrates (Table 2) and by the lack of lithoautotrophic growth with H2 (10% [vol/vol] in gas headspace) as the electron donor and nitrate (10 mM), chlorate (5 and 10 mM), or perchlorate (5 and 10 mM) as the electron acceptor.

Table 2.

Anaerobic and aerobic growth tests of denitrifying strain pMbN1 with different aromatic and nonaromatic compoundsa

| Compound tested (concn)b | Growthc |

|

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic | Aerobic | |

| Aromatic compounds | ||

| 4-Methylbenzoate (1, 2.5) | + | + |

| 3-Methylbenzoate (1, 2) | + | − |

| Benzoate (1, 4) | + | + |

| 2-Aminobenzoate (1, 2) | + | − |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoate (1, 4) | + | − |

| Phenylacetate (1, 4) | + | − |

| Cinnamate (2) | + | + |

| Hydrocinnamate (2) | + | + |

| p-Coumarate (2) | + | + |

| Phenol (0.5, 2) | + | − |

| p-Cresol (0.5, 2) | + | − |

| Benzyl alcohol (0.5, 2) | + | − |

| Benzaldehyde (0.5, 2) | + | − |

| Nonaromatic compounds | ||

| Acetate (1, 5) | + | + |

| Propionate (1, 4) | + | + |

| Butyrate (1, 4) | + | + |

| Isobutyrate (1, 4) | − | + |

| Adipate (1, 5) | + | + |

| Lactate (5, 10) | + | + |

| Malate (1, 5) | + | + |

| Pyruvate (1, 5) | + | + |

| Succinate (1, 5) | + | + |

| Ethanol (1, 5) | + | + |

| Complex media | ||

| Yeast extract (0.5% [wt/vol]) | + | + |

| Peptone (0.5% [wt/vol]) | − | − |

| Casamino acids (0.5, 2% [wt/vol]) | − | − |

Further compounds tested but not utilized by strain pMbN1 under nitrate-reducing or oxic conditions are as follows (concentrations given in percent volume/volume refer to dilutions of poorly water soluble compounds in heptamethylnonane as inert carrier phase): toluene (2%), 4-ethyltoluene (2%), ethylbenzene (2%), propylbenzene (2%), m-xylene (2%), p-xylene (1%), 2-methylbenzoate (1, 2 mM), 4-ethylbenzoate (1, 2 mM), 4-propylbenzoate (0.5, 2 mM), 4-isopropylbenzoate (1, 2 mM), 4-butylbenzoate (0.5, 2 mM), 4-tert-butylbenzoate (0.5, 2 mM), terephthalate (0.5, 2 mM), resorcinol (1 mM), o-cresol (0.5, 2 mM), m-cresol (0.5, 2 mM), 1-phenylpropanol (0.5, 2 mM), (R)-1-phenylethanol (0.5, 2 mM), (S)-1-phenylethanol (0.5, 2 mM), acetophenone (1%), propiophenone (1%), p-cymene (2, 5%), α-phellandrene (1, 2%), α-terpinene (1, 2%), limonene (1, 2%), cyclohexane carboxylate (0.5, 2 mM), cyclohexanol (1, 2%), cyclohexane-1,2-diol (1, 5 mM), n-hexane (2%), glucose (1, 5 mM), fructose (1, 5 mM), all 20 amino acids (0.5, 2 mM), ascorbate (4 mM), formate (10, 20 mM), acetone (0.5, 2 mM).

Each compound was tested at the concentrations shown in parentheses and given in mM unless otherwise indicated.

+, optical density at 660 nm of >0.1; −, no growth.

During growth with 4-methylbenzoate under nitrate (NO3−)-reducing conditions, strain pMbN1 did not intermediately excrete nitrite (NO2−), as do other aromatic compound-degrading denitrifiers, such as “Aromatoleum aromaticum” EbN1 (28). At the end of nitrate-limited growth (10 mM NO3− consumed), no accumulation of ammonium (NH4+) was observed, but formation of 1.3 mM dinitrogen monoxide (N2O) and 2.4 mM dinitrogen (N2) was detected. This suggests that strain pMbN1 reduces nitrate via denitrification. NO3− and NO2− were quantified using an HPLC system equipped with an anion exchange column and an UV detector as described previously (28). NH4+ was spectrophotometrically measured using the indophenol method (23). Formation of N2O and N2 was determined by gas chromatography as recently described (47).

The biochemical challenges imposed by the para-methyl group of 4-methylbenzoate on the dearomatization of this compound as well as on the subsequent reaction sequence (ring cleavage and β-oxidation) raised a question about the capacity of strain pMbN1 to anaerobically oxidize 4-methylbenzoate completely to CO2. Thus, the degradation of this compound coupled to denitrification was balanced (Table 3) using cultures (400 ml) of strain pMbN1 provided with limiting (0.34 mmol) or excess (0.89 mmol) amounts of 4-methylbenzoate relative to the added amount of electron acceptor (3.4 mmol nitrate). Determination of the growth balance was based on quantifying consumption of 4-methylbenzoate and nitrate (by HPLC as described above), as well as on formation of biomass when cultures reached the stationary growth phase. Determination of the dry mass of cells involved a washing step with Tris buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) and drying at 80°C to constant weight. The addition of limiting amounts of 4-methylbenzoate resulted in its complete depletion, while about half of the provided nitrate was recovered. In the experiment with excess amounts of 4-methylbenzoate, 7.2% (±0.6%) of the organic substrate was recovered, while the added nitrate was completely consumed. The average molar growth yield of strain pMbN1 determined from these two organic substrate conditions was 65 g of dry mass per mol 4-methylbenzoate. The amount of electrons formed from dissimilation of 4-methylbenzoate was close to the amount of electrons consumed by nitrate reduction, in agreement with the following stoichiometric equation for complete substrate oxidation:

Table 3.

Quantification of 4-methylbenzoate (substrate) and nitrate consumption and of produced biomass by strain pMbN1a

| Experiment | Amt of substrate added (mmol) | Amt of substrate disappearedb (mmol) | Amt of nitrate disappeared (mmol) | Amt of cell dry mass formedc (mg) | Amt of substrate dissimilatedd (mmol) | Amt of electrons from substrate dissimilatede (mmol) | Amt of electrons consumed by nitrate reductionf (mmol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells with limiting amt of substrate | 0.34 (0.05) | 0.34 (0.13) | 1.4 (0.4) | 21 (3) | 0.25 (0.06) | 9.0 (2.0) | 7.0 (1.8) |

| Cells with excess amt of substrate | 0.89 (0.07) | 0.83 (0.17) | 3.4 (0.2) | 56 (6) | 0.57 (0.05) | 20.7 (2.0) | 17.1 (1.2) |

| Cells without substrate (control) | 0.00g | 0g | 0.0g | 0.0g | 0.0g | ||

| Sterile medium without cells (control) | 0.83g | 0g | 0.0g | 0.0g |

Incubation experiments were carried out in anoxic flat glass bottles with a culture volume of 400 ml containing 3.4 mmol nitrate. Numbers in parentheses represent the standard deviation calculated from triplicate experiments.

Difference between substrate added and substrate recovered at the end of incubation in the culture supernatant.

The amount of cell dry mass added with the inoculum has been subtracted.

Differences between substrate dissimilated and substrate assimilated. The assimilated amount of 4-methylbenzoate was calculated according to the following equation: 17 C8H7O2− + 8 HCO3− + 25 H+ + 50 H2O → 36 C4H7O3. Thus, 1 mg of cell dry mass requires 0.00458 mmol 4-methylbenzoate.

Thirty-six moles of electrons are derived from 1 mol of 4-methylbenzoate if oxidized to CO2.

Electrons consumed = 5 × (nitrate added − nitrate remaining). Nitrite has not been observed in detectable quantities during growth.

No detectable deviations in duplicate experiments.

Calculation of free energy (ΔG°′) is based on standard values (37, 39). The dissimilated amount of 4-methylbenzoate was about 20% higher than required for nitrate reduction, as has previously also been observed for the anaerobic oxidation of ethylbenzene and p-cymene in the denitrifying Aromatoleum strains EbN1 and pCyN1, respectively (13, 28), assumed to result from partial conversion of the substrate to unknown organic compounds.

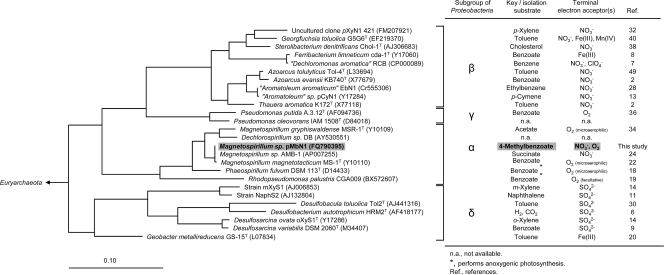

The G+C content of 65.9 mol% was inferred from a merged draft genome sequence of strain pMbN1 (5 Mbp, 251 contigs; M. Kube and R. Reinhardt, personal communication). The 16S rRNA gene sequence was retrieved and finished from the genomic shotgun database using the BLASTN (1) and RNAmmer (17) programs. Phylogenetic analysis using the Silva database (26) and the ARB software package (21) revealed affiliation of strain pMbN1 with the genus Magnetospirillum of the Alphaproteobacteria (34) (Fig. 3). Thus, strain pMbN1 is phylogenetically distinct from the Aromatoleum/Azoarcus/Thauera cluster within the Betaproteobacteria, which comprises the majority of currently known aromatic compound-degrading denitrifiers (15, 43). Some members of the genus Magnetospirillum were previously shown to degrade various aromatic compounds under nitrate-reducing conditions; growth tests with the isomers of methylbenzoate were not reported (35). Among members of the related genus Phaeospirillum, utilization of aromatic compounds seems to be less well studied (18).

Fig 3.

Phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA gene sequence from strain pMbN1. The cluster shown represents selected members of the Proteobacteria. Scale bar, 10% sequence divergence.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniela Lange, Christina Probian, and Ramona Appel (Bremen) for technical assistance. We are grateful to Michael Kube (Berlin) and Richard Reinhardt (Köln) for sequence analysis, Erhard Rhiel and Kathleen Trautwein (both Oldenburg) for help with the electron microscopy and image analysis, Johannes Zedelius (Bremen) for help with GC measurements, Dirk Schüler (München) for testing magnetotaxis, and Friedrich Widdel (Bremen) for support and discussions.

This work was supported by the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SPP1319).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 December 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anders HJ, Kaetzke A, Kämpfer P, Ludwig W, Fuchs G. 1995. Taxonomic position of aromatic-degrading denitrifying pseudomonad strains K172 and KB 740 and their description as new members of the genera Thauera, as Thauera aromatica sp. nov., and Azoarcus, as Azoarcus evansii sp. nov., respectively, members of the beta subclass of the Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:327–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beller HR, Spormann AM, Sharma PK, Cole JR, Reinhard M. 1996. Isolation and characterization of a novel toluene-degrading, sulfate-reducing bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1188–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biegert T, Fuchs G. 1995. Anaerobic oxidation of toluene (analogues) to benzoate (analogues) by whole cells and by cell extracts of a denitrifying Thauera sp. Arch. Microbiol. 163:407–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boll M, Fuchs G, Heider J. 2002. Anaerobic oxidation of aromatic compounds and hydrocarbons. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 6:604–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brysch K, Schneider C, Fuchs G, Widdel F. 1987. Lithoautotrophic growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria, and description of Desulfobacterium autotrophicum gen. nov., sp. nov. Arch. Microbiol. 148:264–274 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chakraborty R, O'Connor SM, Chan E, Coates JD. 2005. Anaerobic degradation of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene compounds by Dechloromonas strain RCB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8649–8655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cummings DE, Caccavo F, Jr, Spring S, Rosenzweig RF. 1999. Ferribacterium limneticum, gen. nov., sp. nov., an Fe(III)-reducing microorganism isolated from mining-impacted freshwater lake sediments. Arch. Microbiol. 171:183–188 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Devereux R, Delaney M, Widdel F, Stahl DA. 1989. Natural relationships among sulfate-reducing eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 171:6689–6695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fuchs G, Boll M, Heider J. 2011. Microbial degradation of aromatic compounds—from one strategy to four. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:803–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galushko A, Minz D, Schink B, Widdel F. 1999. Anaerobic degradation of naphthalene by a pure culture of a novel type of marine sulphate-reducing bacterium. Environ. Microbiol. 1:415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Häner A, Höhener P, Zeyer J. 1995. Degradation of p-xylene by a denitrifying enrichment culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3185–3188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harms G, Rabus R, Widdel F. 1999. Anaerobic degradation of the aromatic plant hydrocarbon p-cymene by newly isolated denitrifying bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 172:303–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harms G, et al. 1999. Anaerobic oxidation of o-xylene, m-xylene, and homologous alkylbenzenes by new types of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:999–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heider J, Fuchs G. 2005. Genus XI. Thauera, p 907–913 In Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM. (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed, vol 2 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kleerebezem R, Pol LW, Lettinga G. 1999. Anaerobic biodegradability of phthalic acid isomers and related compounds. Biodegradation 10:63–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lagesen K, et al. 2007. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:3100–3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lakshmi KV, Sasikala C, Takaichi S, Ramana CV. 2011. Phaeospirillum oryzae sp. nov., a spheroplast-forming, phototrophic alphaproteobacterium from a paddy soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61:1656–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Larimer FW, et al. 2004. Complete genome sequence of the metabolically versatile photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lovley DR, et al. 1993. Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals. Arch. Microbiol. 159:336–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ludwig W, et al. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maratea D, Blakemore RP. 1981. Aquaspirillum magnetotacticum sp. nov., a magnetic spirillum. Int. J. Syst. Microbiol. 31:452–455 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marr L, Cresser MS, Ottendorfer LJ. 1988. Umweltanalytik. Thieme, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsunaga T, Sakaguchi T, Tadokoro F. 1991. Magnetite formation by a magnetic bacterium capable of growing aerobically. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35:651–655 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morasch B, Meckenstock RU. 2005. Anaerobic degradation of p-xylene by a sulfate-reducing enrichment culture. Curr. Microbiol. 51:127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pruesse E, et al. 2007. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:7188–7196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rabus R, Widdel F. 1995. Conversion studies with substrate analogues of toluene in a sulfate-reducing bacterium, strain Tol2. Arch. Microbiol. 164:448–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rabus R, Widdel F. 1995. Anaerobic degradation of ethylbenzene and other aromatic hydrocarbons by new denitrifying bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 163:96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rabus R, Fukui M, Wilkes H, Widdel F. 1996. Degradative capacities and 16S rRNA-targeted whole-cell hybridization of sulfate-reducing bacteria in an anaerobic enrichment culture utilizing alkylbenzenes from crude oil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3605–3613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rabus R, Nordhaus R, Ludwig W, Widdel F. 1993. Complete oxidation of toluene under strictly anoxic conditions by a new sulfate-reducing bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1444–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rabus R, et al. 1999. Anaerobic utilization of alkylbenzenes and n-alkanes from crude oil in an enrichment culture of denitrifying bacteria affiliating with the β-subclass of Proteobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 1:145–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rotaru A-E, Probian C, Wilkes H, Harder J. 2010. Highly enriched Betaproteobacteria growing anaerobically with p-xylene and nitrate. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 71:460–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schüler D, Baeuerlein E. 1998. Dynamics of iron uptake and Fe3O4 biomineralization during aerobic and microaerobic growth of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. J. Bacteriol. 180:159–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schüler D, Schleifer K-H. 2005. Genus IV. Magnetospirillum, p 28–31 In Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM. (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed, vol 2 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shinoda Y, et al. 2005. Anaerobic degradation of aromatic compounds by Magnetospirillum strains: isolation and degradation genes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69:1483–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stanier RY. 1947. Simultaneous adaptation: a new technique for the study of metabolic pathways. J. Bacteriol. 54:339–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Synowietz C. 1983. Organische Verbindungen. In Taschenbuch für Chemiker und Physiker, vol 2 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tarlera S, Denner EBM. 2003. Sterolibacterium denitrificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel cholesterol-oxidizing, denitrifying member of the β-Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1085–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thauer RK, Jungermann K, Decker K. 1977. Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 41:100–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weelink SAB, et al. 2009. A strictly anaerobic betaproteobacterium Georgfuchsia toluolica gen. nov., sp. nov. degrades aromatic compounds with Fe(III), Mn(IV) or nitrate as an electron acceptor. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 70:575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Widdel F, Bak F. 1992. Gram-negative mesophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria, p 3352–3378 In Balows A, Tr̈uper HG, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H. (ed), The prokaryotes, 2nd ed, vol 4 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 42. Widdel F, Knittel K, Galushko A. 2010. Anaerobic hydrocarbon-degrading microorganisms: an overview, chapter 29, p 1997–2021 In Timmis KN. (ed), Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 43. Widdel R, Rabus R. 2001. Anaerobic biodegradation of saturated and aromatic hydrocarbons. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:259–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilkes H, Boreham C, Harms G, Zengler K, Rabus R. 2000. Anaerobic degradation and carbon isotopic fractionation of alkylbenzenes in crude oil by sulphate-reducing bacteria. Org. Geochem. 31:101–115 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wöhlbrand L, Rabus R. 2009. Development of a genetic system for the denitrifying bacterium ‘Aromatoleum aromaticum ’ strain EbN1. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17:41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu J-H, Liu W-T, Tseng I-C, Cheng S-S. 2001. Characterization of a 4-methylbenzoate-degrading methanogenic consortium as determined by small-subunit rDNA sequence analysis. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 91:449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zedelius J, et al. 2011. Alkane degradation under anoxic conditions by a nitrate-reducing bacterium with possible involvement of the electron acceptor in substrate activation. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3:125–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zengler K, Heider J, Rossello-Mora R, Widdel F. 1999. Phototrophic utilization of toluene under anoxic conditions by a new strain of Blastochloris sulfoviridis. Arch. Microbiol. 72:204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhou J, Fries MR, Chee-Sanford JC, Tiedje JM. 1995. Phylogenetic analyses of a new group of denitrifiers capable of anaerobic growth on toluene and description of Azoarcus tolulyticus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:500–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.