Abstract

To determine whether rapid emergence of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis in Israel resulted from an increase in different biotypes or spread of 1 clone, we characterized 87 serovar Infantis isolates on the genotypic and phenotypic levels. The emerging strain comprised 1 genetic clone with a distinct pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profile and a common antimicrobial drug resistance pattern.

Keywords: Bacteria, Salmonella, enteric infections, foodborne infections, Salmonella enterica, Infantis, serovars, antibicrobial resistance, Israel, dispatch

Nontyphoid Salmonella enterica (NTS) is a common cause of foodborne illnesses worldwide. In industrialized countries, S. enterica serovars Enteritidis and Typhimurium are responsible for most NTS infections (1). In Israel, the distribution of NTS infections differs from the global epidemiology for NTS by having a larger representation of serogroups C1 and C2 (serovars Virchow, Hadar, and Infantis) in addition to serovars Enteritidis and Typhimurium (2,3).

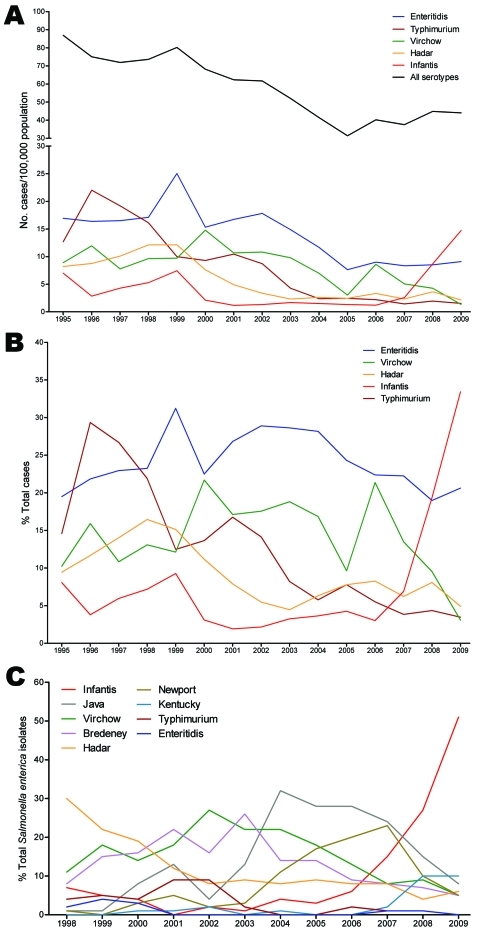

Analysis of annual trends of NTS infections in Israel during 1995–2009 shows a steady decrease in the incidence of these infections, from 86.9 cases/100,000 persons in 1995 to 31.4/100,000 in 2005. During this period, the predominant serovars were Enteritidis, Typhimurium, Virchow, and Hadar, followed by Infantis. Since 2006, annual incidence of NTS has started to increase, rising to 44.0 cases/100,000 persons in 2009. This trend coincided with a sharp increase in incidence of serovar. Infantis from 1.2 cases/100,000 persons in 2001 to 14.7/100,000 in 2009, a 12-fold rise (Figure 1, panel A). The proportion of serovar Infantis increased from <10% of NTS in 1995–2005 to 34% in 2009 (Figure 1, panel B). Furthermore, this steep increase in serovar Infantis from clinical (human) sources correlated with an elevated frequency of serovar Infantis from poultry that became apparent after 2006. Serovar Infantis became the predominant serotype in poultry during 2007–2009, while the prevalences of serovars Enteritidis, Typhimurium, Virchow, Bredeney, Newport, and Paratyphi B var. Java decreased (Figure 1, panel C).

Figure 1.

Salmonellosis epidemiology in Israel, 1995–2009. A) Annual incidence of salmonellosis in Israel. Laboratory-confirmed cases of Salmonella infections per 100,000 population caused by all Salmonella serotypes (black) and by the 5 leading serotypes in Israel. B) The relative contribution (in percentages) of each serotype to the total annual number of Salmonella serotypes. Salmonella infection incidences were constructed according to the number of human Salmonella isolates submitted to the Government Central Laboratories during January 1, 1995–December 31, 2009 (after excluding repeated isolates from the same patient). Data on the Israeli population were derived from the publications of the Israeli Bureau of Statistics. C) Prevalence of S. enterica serovar Infantis and other leading serotypes in poultry. The proportion of different Salmonella serotypes as percentage from the total Salmonella isolates in poultry was analyzed according to routine surveillance in poultry processing plants conducted by veterinary services in 1998–2009. Salmonella isolates have been received, identified, and documented in the National Salmonella Reference Center of Israel.

The Study

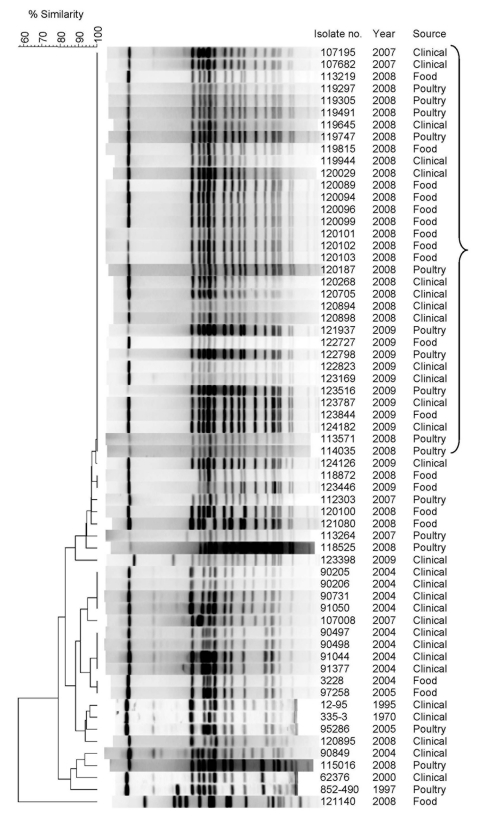

Molecular analysis was used to study whether the rapid emergence of S. enterica ser. Infantis resulted from a general increase in different biotypes or a successful spread of 1 clone. Seventy-one randomly selected isolates of S. enterica ser. Infantis identified in Israel during 2007–2009 (21 human sources, 28 poultry sources, and 22 food sources) and 16 historical strains isolated during 1970–2005 (12 human sources, 2 poultry sources, and 2 food sources) were subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Macrorestriction with the XbaI enzyme discriminated the isolates into 23 distinct profiles (pulsotypes), designated I1–I23. Although the historical isolates showed high diversity in their PFGE patterns, most (58/71, 82%) recent (2007–2009) isolates were homogeneous and showed an indistinguishable PFGE profile (pulsotype I1), which was not found among the historical isolates (Figure 2; Table A1). These results indicate that most of the emerging isolates belong to 1 genetic clone that probably started to spread in Israel sometime during 2005–2007. Furthermore, comparison of the I1 pulsotype with other PFGE profiles through PulseNet (www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/) and PulseNet Europe (www.pulsenetinternational.org/networks/europe.asp) indicated a pattern not reported elsewhere, suggesting the emerging clone is endemic to Israel.

Figure 2.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis isolates from clinical, food, and poultry sources isolated in Israel, 1970–2009, showing a high degree of clonality. Isolate number, year of isolation, and source are indicated. Bracket indicates I1 pulsotype pattern. Macrodigestion performed using XbaI restriction enzyme and genetic similarity (in %) was based on dice coefficients. PFGE was conducted according to the standardized Salmonella protocol Centers for Disease Prevention and Control PulseNet as described (4) by using S. enterica ser. Braenderup H9812 strain as a molecular size standard. Because of space limitations, only 34/58 pulsotype I1 clones are shown. A complete list is provided in Table A1.

To further characterize the isolates, we performed susceptibility tests to 16 antimicrobial compounds. Overall, resistance to 11 antimicrobial agents was detected (Table; Table A1). Two clear differences were found between the strains isolated before and after 2007. First, although 6/16 (38%) of the historical strains were sensitive to all tested antimicrobial agents and 5/16 (31%) were resistant to only 1 (nitrofurantoin), none of the 2007–2009 isolates were sensitive to all of the tested antimicrobial agents. Most (68/71, 96%) of the recent isolates were resistant to >3 antimicrobial agents, which suggests a process of resistance acquisition over time. Second, whereas isolates from 1970–2005 did not share any obvious resistance pattern, most (66/71, 93%) of the 2007–2009 strains showed a combined resistance pattern to nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, and tetracycline with or without additional resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Table). The convergence of the recent serovar Infantis clones to a dominant resistance pattern is consistent with their common PFGE profile and shows that they share high similarity on phenotypic and genotypic levels.

Table. Antimicrobial drug resistance patterns of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis isolates, sorted by isolation year, Israel*.

| Antimicrobial drug resistance profile | PFGE pattern |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970–2005 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

Total |

|||||||||

| I1 | D | I1 | D | I1 | D | I1 | D | ||||||

| Ampicillin, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, cephalothin, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Ampicillin, cefepime, ceftriaxone, cephalothin, cefuroxime, tobramycin | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Nitrofurantoin | 5 | 5 | |||||||||||

| Nitrofurantoin, tetracycline | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Levofloxacin, nalidixic acid | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, tetracycline | 1 | 1 | 37 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 53 | ||||||

| Nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, tetracycline, cephalothin | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, tetracycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 15 | |||||||

| Nalidixic acid, tetracycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Nalidixic acid, tetracycline | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Nalidixic acid, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Sensitive to all tested antimicrobial drugs |

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

| Total | 16 | 2 | 3 | 47 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 87 | |||||

*PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; I1, emerging PFGE pattern; D, different from the emerging pattern.

Next, we characterized the molecular mechanisms responsible for the common antimicrobial drug–resistance phenotype. In bacteria, an efficient means of acquisition and dissemination of resistance genes is through mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, transposons, or integrons (5). Plasmid analysis for 15 emerging (2007–2009) and 7 historical (1970–2005) randomly selected isolates demonstrated that all possessed 1 large plasmid of ≈100 kb. To identify antimicrobial drug resistance genes that are possibly encoded on this plasmid, mating experiments were conducted with a plasmid-free, rifampin-resistant Escherichia coli J5–3 strain and recent S. enterica ser. Infantis isolates harboring tetracycline, nalidixic acid, and nitrofurantoin resistance genes. Conjugation experiments showed the obtained E. coli transconjugants received the large (≈100-kb) plasmid and acquired the tetracycline resistance phenotype but remained susceptible to nalidixic acid and nitrofurantoin. We concluded the tetracycline resistance gene(s) is encoded on the conjugative plasmid. Molecular analysis by PCR showed the tetA gene encoded within the Tn1721 transposon in 6 of 6 randomly selected emerging isolates but in only 1 of 5 older historical strains.

We examined class 1 integrons using PCR primers designed to amplify the variable region of class 1 integrons. All 6 recent isolates bore 1 integron with a variable region of ≈1 kb. Sequencing of the resulting amplicon showed the dfrA1 gene cassette conferring resistance to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole followed by the orfC gene of unknown function. In contrast, 3/5 historical isolates did not possess any integron, and 2/5 contained a disparate integron with a variable region of ≈1.3 kb. Sequencing analysis indicated a different cassette encoded by the aminoglycoside adenyltransferase aadA1 gene conferring resistance to spectinomycin and streptomycin.

Resistance to quinolones is often associated with point mutations in the quinolone-resistance determining region of the gyrA gene (6). To examine this possibility, we determined the gyrA sequence from 6 recent naladixic acid–resistant and 4 naladixic acid–sensitive isolates. All resistant clones showed the same nucleotide substitution from guanine to thymine at position 259 (G259T) in the gyrA gene, resulting in the exchange of asparagine in position 87 to tyrosine (Asp87Tyr) in the quinolone resistance–determining region domain. No mutations were found in the gyrA sequence of the naladixic acid–sensitive isolates, suggesting that the Asp87Tyr point mutation is responsible for the observed naladixic acid–resistance phenotype.

Conclusions

It is likely that environmental selective pressure caused by use of antimicrobial drugs has led to the distribution of appropriate resistant genes. Nitrofurans and sulfonamides, for example, have been widely used to treat infections and promote growth of livestock (7). Because the emerging clone was dominant in all levels of the food chain, including broiler chickens, it is possible that the emerging clone was originally introduced from a poultry source. Recent studies from other countries identified healthy poultry as a potential reservoir of S. enterica ser. Infantis (8–10).

Molecular and phenotypic characterization of recent S. enterica ser. Infantis isolates from different sources and regions in Israel showed high homogeneity of emerging isolates that differ genetically and phenotypically from previously isolated strains. We showed that the emerging clone is multidrug resistant and is characterized by a large conjugative plasmid harboring the Tn1721 transposone and tetA gene, which provides reduced susceptibility to tetracyclines. Additional characteristics include a class 1 integron containing the dfrA1 cassette, a gyrA mutation that mediates nalidixic acid resistance and furthers resistance to nitrofurantoin. Our results suggest the recent emergence of serovar Infantis is an outcome of a clonal expansion and establishment of a specific biotype that took place during a relatively short period. Virulence mechanisms contributing to this phenomenon are the subject of an ongoing study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Noemi Nógrády for providing the Escherichia coli J5-3 RifR strain.

This study was supported by funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Program (PF7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 249241 and from the Chief Scientist of the Israeli Ministry of Health under grant agreement no. 3-00000-6356.

Biography

Dr Gal-Mor is a molecular microbiologist and head of the Infectious Diseases Research Laboratory at the Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel. His primary research interests include microbial pathogenicity and Salmonella virulence and epidemiology.

Table A1. List of the examined Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis isolates, showing source, isolation date, PFGE pattern, and antimicrobial drug susceptibility test results, Israel*.

| Strain no. | Source | Isolation date | PFGE pattern | Susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 335–3 | Archive† | 1970 | I19 | S |

| 12–95 | Archive† | 1995 | I20 | S |

| 852–490 | Poultry | 1997 Sep 19 | I23 | nal,sxt |

| 62376 | Clinical (stool) | 2000 Oct 24 | I22 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 90731 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 Apr 25 | I4 | S |

| 91050 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 Apr 25 | I4 | S |

| 90205 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 May 5 | I4 | S |

| 90206 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 May 12 | I4 | S |

| 90497 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 Jun 3 | I2 | amp, rox, ctr, cf, fd, sxt |

| 90498 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 Jun 3 | I2 | amp, fep, ctr, cf, fd, rox, nn |

| 3228 | Food | 2004 Jun 13 | I3 | fd |

| 90849 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 Jun 21 | I7 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 91044 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 Jul 19 | I2 | fd |

| 91377 | Clinical (stool) | 2004 Aug 4 | I2 | fd |

| 95286 | Poultry | 2005 Mar 28 | I21 | fd |

| 97258 | Food | 2005 Aug 22 | I3 | fd |

| 107008 | Clinical (stool) | 2007 Jan 8 | I5 | fd, tet |

| 107195 | Clinical (stool) | 2007 Jan 15 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 107682 | Clinical (stool) | 2007 Feb 15 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 112303 | Poultry | 2007 Nov 8 | I9 | nal, fd, tet |

| 113264 | Poultry | 2007 Dec 12 | I12 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 113571 | Poultry | 2008 Jan 7 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 114035 | Poultry | 2008 Jan 29 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 114256 | Poultry | 2008 Feb 17 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 114509 | Poultry | 2008 Mar 9 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 115016 | Poultry | 2008 Apr 13 | I8 | nal,tet |

| 115593 | Poultry | 2008 May 18 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 115991 | Poultry | 2008 Jun 1 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 121162 | Food | 2008 Sep 8 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 118525 | Poultry | 2008 Sep 10 | I14 | nal, fd, tet |

| 118872 | Poultry | 2008 Oct 5 | I13 | nal, fd, tet, cf |

| 121056 | Food | 2008 Oct 7 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 121061 | Food | 2008 Oct 12 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 119297 | Poultry | 2008 Oct 19 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 119305 | Poultry | 2008 Oct 26 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 121078 | Food | 2008 Oct 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 121080 | Food | 2008 Oct 30 | I10 | nal, fd, tet |

| 119491 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 2 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 119645 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Nov 4 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 121093 | Food | 2008 Nov 4 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 119747 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 6 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 119944 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Nov 10 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 121102 | Food | 2008 Nov 10 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120029 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Nov 12 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 119815 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 16 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 121116 | Food | 2008 Nov 17 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120309 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Nov 20 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120187 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 21 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 120189 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 21 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120173 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Nov 24 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120191 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 24 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 120186 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Nov 25 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120195 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 27 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120089 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120091 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 120094 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 120096 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120099 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120100 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I11 | lvx, nal |

| 120101 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120102 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 120103 | Food | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120268 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120314 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120321 | Poultry | 2008 Nov 30 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 121135 | Food | 2008 Dec 1 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 120229 | Poultry | 2008 Dec 3 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 120233 | Poultry | 2008 Dec 3 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120540 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Dec 3 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 121140 | Food | 2008 Dec 3 | I16 | nal, tet, sxt |

| 120705 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Dec 10 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120895 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Dec 17 | I6 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120894 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Dec 18 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 120898 | Clinical (stool) | 2008 Dec 18 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 113219 | Poultry | 2008 Dec 27 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 123446 | Food | 2009 Jan 13 | I13 | nal, fd, tet |

| 121937 | Poultry | 2009 Jan 28 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 122727 | Food | 2009 Mar 9 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 123169 | Clinical (abscess) | 2009 Apr 3 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 122798 | Poultry | 2009 Apr 5 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 122823 | Clinical (stool) | 2009 Apr 7 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 123398 | Clinical (stool) | 2009 May 3 | I18 | nal, fd, tet |

| 123516 | Poultry | 2009 May 17 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 124182 | Clinical (blood) | 2009 May 26 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 123787 | Clinical (wound) | 2009 Jun 5 | I1 | nal, fd, tet, sxt |

| 123844 | Food | 2009 Jun 12 | I1 | nal, fd, tet |

| 124126 | Clinical (stool) | 2009 Jun 17 | I17 | nal, fd, tet |

*Eighty-seven randomly selected S. enterica ser. Infantis isolates from human, food, and poultry sources were selected for PFGE analysis and antimicrobial drug susceptibility test. Because Salmonella spp. are reportable pathogens in Israel, the strains were submitted to the Government Central Laboratories by various microbiology laboratories throughout Israel. The National Salmonella Reference Center did final serologic identification. Isolate number, their source, isolation date, and PFGE pattern are indicated. Antibacterial drug susceptibility was tested by using the VITEK 1 system (bioMérieux S.A., Marcy l'Etoile, France) and the GNS-210 VITEK card for gram-negative susceptibility testing. Escherichia coli ATTC 25922 was used as a reference strain. The tested antibacterial agents were amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; ampicillin (MIC >32 μg/mL); rox, cefuroxime; cefepime (MIC >32 μg/mL); ceftriaxone (MIC >64 μg/mL); cefuroxime (MIC ≥32 μg/mL); cephalothin (MIC >32 μg/mL); ciprofloxacin; gentamicin; imipenem; levofloxacin (MIC >8 μg/mL); nalidixic acid (MIC >32 μg/mL); nitrofurantoin (MIC >128 μg/mL); piperacillin/tazobactam; tetracycline (MIC >16 μg/mL); tobramycin (MIC >16 μg/mL); and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (MIC range 80–320 μg/mL). PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; S, sensitive to all examined antibacterial drugs; nal, nalidixic acid; sxt, trimethoprim/sulfamthoxazole; fd, nitrofurantoin; tet, tetracycline; amp, ampicillin; fep, cefepime; ctr, ceftriaxone; cf, cephalothin; nn, tobramycin; lvx, levofloxacin. †National Salmonella spp. archive, source unknown.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Gal-Mor O, Valinsky L, Weinberger M, Guy S, Jaffe J, Ilan Y, et al. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2010 Nov [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1611.100100

References

- 1.Tauxe RV. Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium: successful subtypes in the modern world. In: Scheld WM, Craig WA, Hughes JM, editors. Emerging infections 4. Washington: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. p. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solnik-Isaac H, Weinberger M, Tabak M, Ben-David A, Shachar D, Yaron S. Quinolone resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar Virchow isolates from humans and poultry in Israel: evidence for clonal expansion. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2575–9. 10.1128/JCM.00062-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinberger M, Keller N. Recent trends in the epidemiology of non-typhoid Salmonella and antimicrobial resistance: the Israeli experience and worldwide review. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:513–21. 10.1097/01.qco.0000186851.33844.b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberger M, Solnik-Isaac H, Shachar D, Reisfeld A, Valinsky L, Andorn N, et al. Salmonella enterica serotype Virchow: epidemiology, resistance patterns and molecular characterisation of an invasive Salmonella serotype in Israel. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:999–1005. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fluit AC, Schmitz FJ. Class 1 integrons, gene cassettes, mobility, and epidemiology. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:761–70. 10.1007/s100960050398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopkins KL, Davies RH, Threlfall EJ. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: recent developments. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;25:358–73. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafson RH. Antibiotics use in agriculture: an overview. In: Moats WA, editor. Agricultural uses of antibiotics. Washington: American Chemical Society; 1986. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nogrady N, Kardos G, Bistyak A, Turcsanyi I, Meszaros J, Galantai Z, et al. Prevalence and characterization of Salmonella Infantis isolates originating from different points of the broiler chicken–human food chain in Hungary. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;127:162–7. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nogrady N, Toth A, Kostyak A, Paszti J, Nagy B. Emergence of multidrug-resistant clones of Salmonella Infantis in broiler chickens and humans in Hungary. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:645–8. 10.1093/jac/dkm249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahada F, Sugiyama H, Chuma T, Sueyoshi M, Okamoto K. Genetic analysis of multi-drug resistance and the clonal dissemination of beta-lactam resistance in Salmonella Infantis isolated from broilers. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:136–41. Epub 2009 Jul 10. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]