Abstract

An outbreak of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli in a neonatal care unit began with transmission from a mother to her newborn twins during vaginal delivery. Subsequently, infection spread by healthcare worker contact with other neonates; a healthcare worker also was infected. Knowledge about transmission may improve infection control measures.

Keywords: Outbreak, transmission, extended-spectrum β-lactamase, ESBL, Escherichia coli, neonatal care unit, nosocomial infections, bacteria, Switzerland, dispatch

Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae expressing extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) are among the most multidrug-resistant pathogens in hospitals and are spreading worldwide (1–3). Infections caused by ESBL–producing organisms have resulted in poor outcomes, reduced rates of clinical and microbiological responses, longer hospital stays, and greater hospital expenses (4,5). Multiple outbreaks of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in intensive care units (ICUs) and increased rates of illness and death, especially in neonatal ICUs, have been reported (6–10). Physical contact is the most likely mode of transmission. The gastrointestinal tract of colonized or infected patients is the most frequent reservoir. Several studies indicate that transient carriage of bacteria on the hands of healthcare workers (HCWs) may lead to transmission to patients (7,11).

We report an outbreak of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL E. coli) in a neonatal intermediate care unit. Initial transmission was from a mother to her newborn twins and subsequently by physical contact of HCWs with other patients; an HCW also was infected.

The Study

The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland, has 94 beds; ≈2,000 babies are delivered there each year. The neonatal unit includes 12 beds for healthy newborns and 9 beds for infants requiring intermediate care.

A 29-year-old woman with dichorionic twin pregnancy was admitted to the antenatal care unit at 32 weeks’ gestation because of spontaneous preterm rupture of membranes of the first twin. Her medical history was unremarkable. Screening results for gestational diabetes, as well as urinary controls and vaginal swabs for group B Streptococcus, were negative. After confirmation of preterm rupture of membranes by ultrasound and vaginal examination, therapy was initiated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (3 × 2.2 g/d) for 10 days, tocolysis with betamimetics (hexoprenaline) until 34 weeks’ gestation, and 1 course of steroids for lung maturation (betamethasone 2 × 12 mg with an interval of 24 h).

Five weeks later, the woman spontaneously delivered 2 healthy boys (1,920 g, Apgar scores 9/10/10; and 2,045 g, Apgar scores 8/9/9) under epidural analgesia with placement of a urinary catheter. Two days after delivery, an asymptomatic urinary tract infection with ESBL-E. coli was detected in the mother; it was treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for 7 days. Follow-up urinalysis was negative for ESBL E. coli; however, rectal swab performed to document colonization was positive for ESBL E. coli. This pathogen persisted for >7 months after delivery, after which the patient was lost to follow-up.

Both twins were initially admitted to the neonatal intermediate care unit because of their prematurity. Six days after birth, screening rectal swabs confirmed colonization with ESBL E. coli in both neonates. The twins did not show clinical signs of infection and were discharged on their 20th day.

Screening of the 6 other neonates in the neonatal intermediate care unit during the twins’ stay showed that 3 were colonized. In addition, rectal screening of 31 HCWs indicated that 2 (7%) were positive for ESBL E. coli. Invasive infection did not develop in any of the 3 neonates colonized with ESBL E. coli.

Monthly follow-up screening was performed for the 2 HCWs who were positive for ESBL E. coli. They continued working after reeducation about general hygiene precautions. One HCW left her job at the hospital and was lost to follow-up; the other was negative for ESBL E. coli at 2-month follow-up.

Rectal swab specimens for surveillance of intestinal carriage were obtained from all patients in the neonatal intermediate care unit during the outbreak and at 2 weeks, 5 months, and 7 months after the outbreak. Screening for ESBL E. coli carriage among HCWs was performed by obtaining rectal swabs.

Cultures were performed by using CHROMagar orientation medium (Becton Dickinson BBL Diagnostics, Sparks, MD, USA). ESBL production was identified according to the guidelines of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (12). Routine susceptibility testing was performed by microbroth dilution (Micronaut-S; Merlin, Bornheim-Hersel, Germany). Four cephalosporins (cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, and aztreonam) were used for screening. If >1 of the cephalosporins showed increased MICs, ESBL E. coli was confirmed with Etest strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) containing cefotaxime or ceftazidime, each with and without clavulanic acid.

Molecular typing was performed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). ESBL was molecularly confirmed by PCR amplifying genes for TEM, SHV, and CTX-M β-lactamases. Amplicons were sequenced by using an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

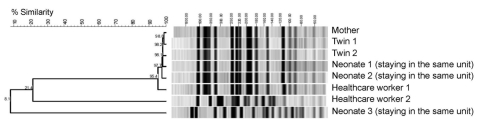

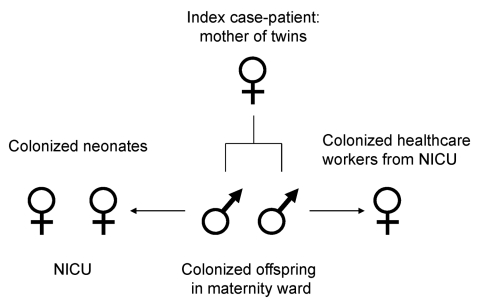

Genotyping by PFGE showed 1 dominant ESBL E. coli strain; 2 different genotypes were found in 1 HCW and in 1 of the screened neonates staying in the same unit as the twins (Figure 1). The outbreak strain was found in the index patient, her twins, 2 neonates staying in the neonatal intermediate care unit at the same time, and 1 HCW (Figure 2). Sequencing of the ESBL gene showed TEM-29 type. Surveillance cultures performed on all patients in the neonatal intermediate care unit indicated no further ESBL E. coli was present at 2 weeks, 5 months, and 7 months after the outbreak.

Figure 1.

Molecular typing of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Dendrogram shows a cluster of 6 isolates with identical banding pattern and 2 isolates with 2 distinct patterns.

Figure 2.

Spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli outbreak. NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Before the outbreak, a quaternary ammonium–based disinfectant was used daily to clean the neonatal unit. HCWs routinely cared for healthy babies without using gloves but did use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer. Products for patient care were shared among neonates; in particular, no protective covering was used for clinical thermometers.

After screening showed ESBL E. coli, reinforced infection control strategies were established. A schedule of training sessions emphasizing proper hand hygiene, routine use of protective covering for clinical thermometers, environmental cleaning using an aldehyde-based disinfectant, and routine use of gloves and gowns for any patient contact (particularly changing diapers) was instituted. Furthermore, separate care products were used for each neonate.

Conclusions

We report an outbreak caused by transmission of ESBL E. coli from a mother to her newborn twins and subsequent spread to other neonates and 1 HCW. The mother was most likely colonized before hospitalization, and a urinary tract infection developed peripartum. Transmission by contact during vaginal delivery of the twins and transmission by physical contact to 1 of the HCWs and the other neonates was the most likely mode of transmission. We interpret the detection of ESBL E. coli infection in 1 of the neonates and the other HCW as a coincidence because both had a different genotype (TEM-12) and PFGE pattern type of ESBL E. coli.

Because we screened only for ESBL E. coli, we might have underestimated the true extent of the outbreak. However, the ESBL-encoding gene, which is on a plasmid, could have been transferred to other Enterobacteraceae and would have been missed. Risk factors for colonization in newborns include low birthweight, duration of hospitalization, total parenteral nutrition, previous use of antimicrobial drugs, and mechanical ventilation in a neonatal ICU (13). In the intermediate care setting, breastfeeding was associated with a lower risk for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (14) because breastfed neonates have more contact with their mothers and therefore are possibly less frequently handled by HCWs. Our patients had only 1 identified risk factor: the twins from the colonized mother had low birthweight; the other neonates had no risk factors. Improved infection control strategies may be necessary to limit spread of ESBL E. coli in maternity wards because transmission to neonates during delivery is possible. A feasible approach could be to screen mothers whose neonates need to be transferred to ICUs; an outbreak in this setting would be particularly harmful.

Biography

Dr Tschudin-Sutter is a board-certified internal medicine physician currently completing a fellowship in hospital epidemiology and infectious diseases at the University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland. Her research emphasis is multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Tschudin-Sutter S, Frei R, Battegay M, Hoesli I, Widmer AF. Extended spectrum β-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli in neonatal care unit. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2010 Nov [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1611.100366

References

- 1.Ben-Ami R, Rodríguez-Baño J, Arslan H, Pitout JD, Quentin C, Calbo ES, et al. A multinational survey of risk factors for infection with extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae in nonhospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:682–90. 10.1086/604713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valverde A, Coque TM, Sánchez-Moreno MP, Rollán A, Baquero F, Cantón R. Dramatic increase in prevalence of fecal carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae during nonoutbreak situations in Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4769–75. 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4769-4775.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kader AA, Kumar A, Kamath KA. Fecal carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients and asymptomatic healthy individuals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1114–6. 10.1086/519865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lautenbach E, Patel JB, Bilker WB, Edelstein PH, Fishman NO. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: risk factors for infection and impact of resistance on outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1162–71. 10.1086/319757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterson DL, Ko WC, Von Gottberg A, Mohapatra S, Casellas JM, Goossens H, et al. Antibiotic therapy for Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:31. 10.1086/420816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macrae MB, Shannon KP, Rayner DM, Kaiser AM, Hoffman PN, French GL. A simultaneous outbreak on a neonatal unit of two strains of multiple antibiotic resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae controllable only by ward closure. J Hosp Infect. 2001;49:183–92. 10.1053/jhin.2001.1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A, Della-Latta P, Todd B, San Gabriel P, Haas J, Wu F, et al. Outbreak of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal intensive care unit linked to artificial nails. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:210–5. 10.1086/502380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayan M, Kuzucu C, Durmaz R, Aktas E, Cizmeci Z. Analysis of three outbreaks due to Klebsiella species in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:495–500. 10.1086/502245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurent C, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Rost F, Strale H, Vincent JL, Deplano A, et al. Intensive care unit outbreak of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Klebsiella pneumoniae controlled by cohorting patients and reinforcing infection control measures. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:517–24. 10.1086/588004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu TL, Chia JH, Su LH, Kuo AJ, Chu C, Chiu CH. Dissemination of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriacae in pediatric intensive care units. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4836–8. 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4836-4838.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:657–86. 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; eighteenth informational supplement. CLSI document M100–S18. Wayne (PA): The Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Hady H, Hawas S, El-Daker M, El-Kady R. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2008;28:685–90. 10.1038/jp.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassettari VC, da Silveira IR, Dropa M, Lincopan N, Mamizuka EM, Matté MH, et al. Risk factors for colonisation of newborn infants during an outbreak of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in an intermediate-risk neonatal unit. J Hosp Infect. 2009;71:340–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]